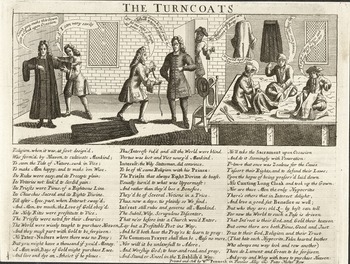

Ridicule in The Turncoats (1711) was an uneasy mixture of celebration and concern (Figure 1).Footnote 1 The print celebrated the Tory victory in the general election of autumn 1710 as a triumph of sincerity over hypocrisy. At the same time, it expressed concern that, despite that victory, hypocrisy continued to corrupt the Protestant interest. A Tory victory was a victory for the high church party in England's established church over those which it felt threatened that church, namely those Dissenting Protestants and low churchmen who had advocated for Dissenters’ place in English public life since their toleration after the 1688–9 Revolution. The fall of the Whig government in 1710 (and, with it, the low church interest) meant that Dissent would not be treated as leniently as it had been for the past twenty years, a change in fortunes that caused many ministers to conform to the established church that they had long claimed to be popish, seemingly putting preferment before principle. The Turncoats scoffed at the deftness of these conversions. It shows two ministers being measured in a tailor's shop, turning their coats from Dissenting cloaks to high church gowns, and exposing their hypocrisy in the process. ‘Can't you make the gown into a cloak upon occasion?’, the first minister asks his tailor, flaunting his intention to turn again in the future. ‘Let my gown by lin'd with a cloak to turn at pleasure’, demands the second, pointing at the cloak on the floor to indicate he will switch again when the situation suits. The hypocrisy is galling. But the tailors have the Dissenters’ measure: ‘Sir, let me take the length of your conscience’.

Figure 1. The Turncoats (1711). Reproduced by permission of The British Museum. Copyright of the Trustees of The British Museum.

As we unpick the scene, mockery piles on top of mockery. The ministers are derided by their social inferiors. An apprentice looks in on the workshop purely to mock them, while on the right, three gossiping labourers jest that they ‘need not fear cucumber time’ (i.e. summer, normally a quiet season for tailors), because they will be busy sewing new gowns. Old jokes about hypocrites are picked, magpie-like, from the bricolage of popular culture and rearranged into a new conceit: ‘My masters are vicars of Bray’, chides the apprentice at the back of the scene, referring to the time-serving cleric of proverb, print and song, who saved his own skin by shifting with the times. ‘My masters can please trimmers’, replies one of the labourers, riffing on multiple definitions of ‘trimming’, combining the tailors (trimming clothes), Dissenters (trimming consciences) and ‘Trimmer’, a slur against clergy or politicians who changed parties out of self-interest.Footnote 2 Hypocrites ‘trimmed’ in the nautical sense, in which a ship's sails were adjusted to make best use of the wind. Turncoat clergy changed vestments to find their best ‘trim’ for gain.

There is, therefore, a lot of ridicule in The Turncoats. But to what end? What did all this laughter do? This print (and many others produced during 1709–11) was part of a tradition of polemic that used mockery to expose religious hypocrisy to aggressive, moral emotions: anger, contempt and shame. Such polemic dated from the Reformation. Protestants denigrated Roman Catholic doctrine and tradition as a gaudy mockery of Christian truth, deriding its miracles and scoffing at its saints to expose it as Antichrist, the arch-hypocrite.Footnote 3 This was a punishing, moral laughter which justified the Reformation by scorning what had gone before it.

There was much of this polemic in The Turncoats: Dissenting hypocrites were laughed to scorn. This is underscored by the politics of other graphic satires issued by The Turncoats’ publisher, William Pennock, in 1710–11, which took a pro-Tory and -high church, and anti-Whig, -low church and -Dissent, stance.Footnote 4 It is argued below, however, that The Turncoats pushed at the conventional boundaries of party politics, decrying religious hypocrisy in general, alongside condemning Dissenting hypocrisy in particular.Footnote 5 Ridicule reflected acute concerns about the prevalence of hypocrisy in public life which was a crucial factor in the crisis of politics during the first age of party (c.1678–1714).Footnote 6 The public's growing political importance as voters, petitioners and readers was matched by growing worries about its ability to judge fairly in an era of rampant misrepresentation in which swollen volumes of partisan news used shams, cheats and frauds to distort truth to party ends. ‘Hypocrisy is the profitable and consequently the reigning vice of the age’, worried Richard Kingston, Jacobite turned informer, in 1709.Footnote 7 Its pervasiveness during the first decade of the eighteenth century provoked a moral panic that marked the collapse of trust in public life.Footnote 8

During that crisis, mocking exposés of religious hypocrisy continued to express anger, contempt and shame as they had since the Reformation. But ridicule also did something else: it provided release from anxieties caused by the perception that hypocrisy was prevalent in public life. How laughter was understood in early modern culture is revealing on this score. One theory saw laughter as a mark of the malicious joy found in feeling superior to someone or something else: we laugh at what is contemptible. Another theory, found most commonly in medical writing, saw laughter as relieving, a physical release of tensions in mind and body caused by feelings of misery or melancholy. We see both superiority and relief in The Turncoats’ mockery of hypocrisy. The print ridiculed the contemptible (Dissenters) to celebrate the Tory-high church as morally superior; and it expressed horror that, despite that victory, hypocrisy was still a threat, for hypocrites were joining the church.

Dissent and Hypocrisy

The roots of the hostility to Dissent portrayed in The Turncoats lay in the fallout of the 1688 Revolution. The nature of the revolution meant that no group was safe from accusations of hypocrisy. The established church struggled to reconcile the removal of James II with the doctrines of passive obedience and non-resistance. For nonjuring Anglicans – who refused to swear oaths of allegiance to William and Mary, because doing so violated those sworn to James – there was no reconciliation: 1688 was an affront to God and conscience.Footnote 9 That most Anglican clergy did take the oath was unsettling, because it smacked of interest trouncing principle and exposed an uncomfortable truth: hypocrisy was necessary for the new settlement to work. High churchmen accused their low church opponents of selling out the Church of England by supporting toleration and advocating for the place of Dissent within a comprehensive Protestant interest. High churchmen were in turn accused of hiding Jacobite sympathies under a pretended royalism; and Dissenters’ sober dress and distain for socializing drew charges of hypocrisy, viewed as public displays of piety that masked the fanaticism that threatened England's church and state in the early eighteenth century as acutely as they had in the mid-seventeenth.Footnote 10 Most troubling, however, was the fact that religion had become a plaything of politics. Whigs and Tories were accused of adopting positions on religious matters to con the public and win votes. Mark Knights has shown that, by 1710, it was widely accepted that ‘religious language was … used as a veneer covering private, sectional or group ends’ and was ‘deliberately chosen to hide nakedly political ambitions’.Footnote 11 Religious politics descended into the competitive unmasking of hypocrisy in which all sides decried their opponents’ mendacity at all times. This caused a collapse in public trust in politics, provoking a moral panic about the decline of honesty and sincerity in English society. Where could the abuse of faith lead, but to apathy or atheism? As the author of Moderation Truly Stated (1704) noted, pretending in matters of faith ‘gives religion the deepest wounds’.Footnote 12 No trust, no faith.

Much of this alarm can be traced to the religious settlement imposed by the Toleration Act of 1689. The act permitted all Trinitarian Protestant congregations who dissented from the established church to worship in their own meeting houses, jettisoning the ideal of uniformity that had been a cornerstone of the English Reformation.Footnote 13 Dissenters benefited significantly from this change. Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers and other minority Protestant groups were no longer persecuted for practising their faith (as they had been from 1662). Their new freedom to worship was accompanied by formal recognition that they were part of England's Protestant interest, partners with the established church in the fight against popery.Footnote 14 Considering that ‘puritans’ had been joined with ‘popery’ as the twin terrors of that interest in conformist Protestant thought for over a century, this marked a substantial change in the public status of Dissent.

It was an embittered partnership, however. As Ralph Stevens has shown, the act did not end Anglican-Dissenter hostilities, but reframed them in the new context of the post-Revolution constitution.Footnote 15 Tensions reflected differing interpretations of the Toleration Act. For many Dissenters, the 1689 legislation had not gone far enough. It was merely a step towards full freedom, which could only be realized with the abolition of the penal code, a platform on which to agitate against the legal restrictions that continued to make their position in English society unequal. For many Anglicans, the 1689 Toleration was merely a temporary indulgence of Dissent, not an unbudgeable cornerstone of the constitution. High churchmen refused to accept the permanence of the new plural religious society, or the declining role of the established church in that society which followed on from it. They worked to restrain the scope of Dissenters’ new religious freedoms in the period up to 1720, after which the declining political influence of their Tory allies left them with no feasible means of opposition.Footnote 16 Toleration created a religious marketplace, and the Dissenters’ claiming their new place in public life caused the established church to fear the loss of parishioners at a local level, and the control of public life at a national one. The construction of new meeting houses, funerals of prominent parishioners, and the growing involvement of Dissenters in the provision of children's education became new flashpoints of old intolerances in an era of legalized religious difference.Footnote 17

Occasional conformity was the most serious of those flashpoints. The political authority of the Church of England was protected by the 1688/9 constitutions, which barred Dissenters from holding political office by requiring all office-holders to prove that they had received communion in the established church.Footnote 18 Dissenters responded by practising occasional conformity, taking the Anglican sacrament once annually (while otherwise continuing to attend their meeting houses), thereby qualifying for political office via an unabashed act of public hypocrisy, receiving communion in a church that they had long held to be popish and persecutory, for naked political gain. They ‘play[ed] bopeep with God Almighty’, teased Daniel Defoe, for reasons of ‘politick’.Footnote 19

The debate about occasional conformity mapped onto existing divisions in England's fractious Protestant fraternity. Both the Whig politicians who steered the governments of William and Mary, and Anne, and the low churchmen who dominated the churches of their period, winked at occasional conformity as a means of promoting unity between Protestants, and extending the principle of toleration of the Revolution settlement.Footnote 20 This leniency enraged high churchmen, who worried that allowing Dissenters into the political establishment gave them a platform from which to spread sedition and irreligion, and engaged in a bitter campaign to stop occasional conformity.Footnote 21 Three bills, submitted in the parliamentary sessions of 1702–3, 1703–4 and 1704–5, proposed punitive fines on office-holders who attended Dissenting meetings. Attempts to ‘tack’ the third bill onto the granting of a subsidy necessary to continue war with France provoked fury and pushed the Whig regime to the point of crisis.Footnote 22 The bills were defeated, but they underlined the extent to which concerns about Dissent and religious hypocrisy more generally destabilized English politics in the first decades of the eighteenth century.

Dissenting hypocrisy caused consternation because it played into long-standing stereotypes. Since the late sixteenth century, hypocrisy had been a major element of the anti-puritanism that now informed hostility to Dissent. ‘Puritans’ were popularly seen as irrational and seditious hypocrites, who hid their lust for power behind a pretend piety.Footnote 23 Those stereotypes had a long half-life in parishes across eighteenth-century England, and informed the ‘graduated layers of religious exclusivity’ which, as Carys Brown has shown, peppered everyday interactions between Protestant denominations in eighteenth-century England.Footnote 24 Yet hypocrisy took on new resonance after 1689, because of the emergence of polite, sober modes of speech, manners and behaviour as the guiding ideal of public life. Politeness rejected zeal in favour of moderation to limit the potential of religion to foment division.Footnote 25 Zealous or ‘enthusiastic’ displays of faith, such as the austere piety of many Dissenting congregations, were now deemed to be impolite, the foundation of the fanaticism which (in Anglican eyes) had caused the civil wars of the previous century. Politeness placed Dissenters in a bind. Conforming to the new mores led to suspicions of insincerity; rejecting them, to charges of hypocrisy and to accusations that these were pious performances that showed that Dissenters thought themselves to be ‘better’ Protestants than their Anglican brethren. Stereotypes drew connections between Dissenters’ unfashionable dress and their outmoded zeal, presenting their clothing as a cloak for their sedition that proved they should not be tolerated.Footnote 26

That Dissent had strong support within the Whig regimes of both William and Mary, and Anne, played into the Tory-high church ‘Church in Danger’ campaign that expressed fears that, since 1688, a conspiracy had been at work to undermine the established church. The campaign saw toleration, latitudinarianism and occasional conformity as corruptions of the constitution that provided platforms for religious heterodoxy and republican politics bent on undermining society.Footnote 27 Occasional conformity was about more than Dissent. It was totemic of broader tensions in the Revolution settlement about toleration and the place of the established church in the constitution. That some public figures were prepared to dissemble to gain power, and other political figures and parties were prepared to permit that dissembling, pointed to the decline of honesty, sincerity and piety in public life. This ‘Church in Danger’ platform was crucial to winning the Tory-high church party a landslide victory in the 1710 General Election.Footnote 28

The Sacheverell Affair

Doctor Henry Sacheverell (1674–1724) was the unlikely architect of this Tory-turn in late Stuart politics. A ‘Church in Danger’ preacher and long-standing anti-Dissenter firebrand, Sacheverell was tried for high crimes and misdemeanours in February and March 1710, having indicted the Whig government in his 5 November sermon at St Paul's Cathedral, The Perils of False Brethren.Footnote 29 In that sermon, Sacheverell proclaimed the established church to be corrupted by hypocrites, just like the church of Corinth described by St Paul. A conspiracy of Whigs, low churchmen and Dissenters had sought the undoing of Protestant England since 1688 by pursuing toleration, permitting latitude in doctrine and liturgy, and ignoring occasional conformity, thereby allowing heresy and sedition footholds in power. These false brethren, and the apostate Tories or high churchmen who did nothing to stop them, were hypocrites, pretend Protestants who put political interest over principle. What Sacheverell said was made doubly offensive by when he said it. Fifth of November sermons were a ritual set piece of Protestant memory, uniting parishes across England in collective thanksgiving for their nation's special place in providence. Preachers were expected to relate 5 November 1605 (the Gunpowder Plot) to 5 November 1688 (William of Orange's landing at Torbay) as a double deliverance from popery.Footnote 30 Sacheverell turned this celebration into mourning, damning the revolution as a seditious contravention of the church's doctrine (passive obedience and non-resistance), and the toleration as an act of schism.

At first, Sacheverell was laughed at, his sermon dismissed as having more spleen than substance. ‘The roaring of this beast ought to give you no manner of disturb[ance]’, affirmed Daniel Defoe, ‘You ought to laugh at him, let him alone; he'll vent his gall, and then he'll be quiet’.Footnote 31 Defoe was wrong: ire proved to be catching. Sacheverell was a lightning rod for pent-up prejudice against Dissent. On 1 March 1710, riotous crowds of Sacheverell supporters sacked meeting houses, tearing one down in Lincoln's Inn Fields, brick by brick, before celebrating their iconoclasm with a giant bonfire of its gutted contents.Footnote 32 Sacheverell's popularity was a captivating blend of sympathy and infamy that ensured his trial generated more public interest than any since Charles I's in 1649. Christopher Wren employed fifty workmen to build the stands commissioned for the crowds expected in Westminster Hall, ripping out vendors’ stalls to make the auditorium as large as possible, and there was a frenzied black-market competition for tickets.Footnote 33 News that Sacheverell would preach at St Saviour's, Southwark, after being released on bail, left that church packed to the rafters. Rumours in the pews that he was actually at Newington caused the panicked crowd to rush there instead. On the first day of the trial proceedings, Sacheverell was collected from his lodgings in Temple in a coach made largely of glass, a ‘tawdry chariot’ from which he was visible to the crowds who lined the streets daily to wave his cavalcade of eight coaches and 400 supporters on their path to Westminster, where they met crowds of ticket holders who had been gathering since 7 a.m., two hours before the court's doors would open, and five before the trial would begin.Footnote 34

The trial was easily spun as proof that the conspiracy against the church of which Sacheverell spoke was real. He was found guilty, but the queen insisted on only a token punishment, a humiliation for the government that was greeted as a deliverance for the established church, and set in motion the downfall of the Whig regime. The Tories made full use of their new champion, trotting Sacheverell out as the prized prig of the ‘Church in Danger’ campaign to win seats across England in the general election that November.Footnote 35 In that election, and the campaign against Dissent that followed, he was a totem of sincerity besting hypocrisy. Sacheverell was briefly the most famous man in England, ‘Huzza'd by the mob like a prize fighter’ wherever he went.Footnote 36 Published on 25 November 1709, and selling over 100,000 copies by the following March, The Perils of False Brethren earned him an estimated readership of 250,000, equivalent to the entire electorate.Footnote 37 Sacheverell was painted by Thomas Gibson, a leading portrait artist of the period, and mezzotint reproductions of his image flooded London during the trial in February and March 1710, and were widely displayed in private homes and public spaces as a mark of support for Sacheverell and the church his supporters felt was on trial with him.Footnote 38 A generation later, his portrait still stood as an icon of popular Toryism. Hogarth sneered at it, pasting Sacheverell's face at Moll's bedside in plate 3 of the ‘Harlot's Progress’ to mock cheap veneers of respectability (Figure 2).Footnote 39

Figure 2. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress (1732), plate 3. Reproduced by permission of The British Museum. Copyright of the Trustees of The British Museum.

Gilbert Burnet remembered the Sacheverell affair with astonishment as ‘one of the most extraordinary transactions in my time’.Footnote 40 The most extraordinary aspect of the affair was its heat, which shocked contemporaries. Sacheverell entered the pulpit of St Paul's Cathedral with ‘red overspread[ing] his face [and a] goggling wildness [in] his eyes … like a sybil to the mouth of her cave’, before proceeding to preach on the fiery tip of fury.Footnote 41 ‘I fancy he had bankrupt all the oysterwomen, porters, watermen, coachmen and carmen in town to make up his collection’, exclaimed one Whig, taken aback by the sermon's tone.Footnote 42 ‘I could not have imagined if I had not actually heard it myself’, said the Rev. John Bennett, that ‘so much heat, passion, violence and scurrilous language, to say no worse of it, could have come from a Protestant pulpit’.Footnote 43 Sacheverell had many critics. Even high churchmen sympathetic to his cause were embarrassed that his attack on the church and government was guilty of the sins with which he charged the Dissenters: enthusiasm, sedition and zeal. Much of the polemic that emerged from the trial, and the Tory turn that followed, proved his equal in raillery.

Sacheverell soon changed tack. As Brian Cowan has demonstrated, during his speech in his own defence on 9 March 1710, Sacheverell presented himself as a ‘living martyr of the high church cause’.Footnote 44 Even his opponents thought that the sympathy his performance elicited was remarkable.Footnote 45 Sacheverell's temperate, humble speech won him victory in the court of public opinion. Printed copies ran through twenty editions in 1710 alone and shaped the representation of Sacheverell in the public sphere, coupling him with other Anglican martyrs, Archbishop William Laud and Charles I (whose portrait he was often pictured holding).Footnote 46 Cowan has shown that the speech also changed what was on trial. The Whig prosecution had been designed to defend the 1688 Revolution by condemning the high church principles that Sacheverell advocated so vehemently in his 5 November sermon: passive obedience and non-resistance. Styling himself as a martyr allowed Sacheverell to sidestep matters of controversy and present the trial as a partisan attack on the church: he was being persecuted for doing his duties as a minister, preaching the church's doctrine and rebuking sin.Footnote 47 Moderate language and pathetic oratory were essential to Sacheverell's studied performance of sincerity.

The crude logic of polemic dictated that if Sacheverell embodied sincerity, his opponents must embody hypocrisy. In the winter of 1710–11, Burnet was mocked as a hypocrite and so, with even less mercy, was the Whig cleric Benjamin Hoadly, who became Sacheverell's antithesis, the low church champion to the doctor's high. Dissenters were vilified with equal ferocity. The scathing tone of The Preaching-Weathercock: A Paradox (1712) by John Dunton, bookseller and founder of the Athenian Society, was typical.Footnote 48 Dunton attacked William Richardson, a former Presbyterian minister in Clerkenwell who had taken orders in the established church in 1711. Richardson's change of heart was public: he published the sermon delivered in his new parish of St Mary's, Whitechapel, in which he justified his conversion. It also brought him speedy preferment: within a year, he was chaplain to the earl of Londonderry. This did not make him popular. Nor did his telling his former brethren that there were no legitimate reasons for their Dissent from the established church, a choice he now labelled fanatical.Footnote 49 The gall of this was too much. Richardson became an embodiment of Dissenting hypocrisy, accused by Anglicans and Dissenters alike of converting for self-interest and gain. Even his own family condemned him.Footnote 50 Dunton had sharpened his hatchet:

Another – VICAR OF BRAY – (or Preaching Weathercock) is Turncoat Will – For with the FANATICS, you are Demure and Saintish – with HIGH CHURCH you can rail at Dissenters, and call ‘em Schismaticks – with the TRIMMERS, you're moderate, and good Natur'd …. And with ALL PARTIES, you can Conform, Transform, Reform, and turn to any Form for the sake of a good Living…..a meer VICAR OF BRAY….with the infamous Character of being TURNCOAT….and your High-flying Brother [Sacheverell] tells you as much in that scandalous sermon he bellow'd out at St. Pauls….But assure your self that your Turning thus with every Wind, gains you neither Credit, not Profit, but makes a sort of Preaching Jest, or Vicar of Bray.Footnote 51

Richardson was a turncoat, a trimmer and a Vicar of Bray: the very insults hurled at Dissenting converts in The Turncoats.

Vicars of Bray

The Turncoats’ image, then, was an assortment of clichés. It asked its viewers to laugh at jokes they knew well and its ridicule was potent because it was direct. ‘Trimmers’, ‘turncoats’ and ‘Vicars of Bray’ were commonplaces, instantly familiar images that worked as insults because the associations of their mockery – deceit, insincerity, interest – were immediate. In the wake of the Sacheverell affair and the Tory-turn in politics that followed it, those associations had a new resonance. The alarmism of Sacheverell and the ‘Church in Danger’ campaign made commonplace images of hypocrisy more urgent.

Commonplace insults were remarkably changeable – they meant different things in different contexts. The Vicar of Bray is an instructive example. The vicar was a shorthand for a weathercock cleric whose principles turned with the prevailing wind. The proverb was recorded in Thomas Fuller's The Worthies of England (1662):

The vivacious vicar [of Bray] living under King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Mary, and Queen Elizabeth, was first a papist, then a protestant, then a papist, then a protestant again. He had seen some martyrs burnt (two miles off) at Windsor and found this fire too hot for his tender temper.

This vicar, being taxed by one for being a turncoat and an inconstant changeling, said ‘not so, for I always kept my principle, which is this – to live and die the Vicar of Bray’.Footnote 52

The tone here was merry, not mocking. Fuller teased clerical hypocrisy – he did not attack it. The proverb was circulated as a pleasantry in the period's compendiums. Its incongruous humour (an a-moral priest) was enjoyed as an absurdity in works like ‘The Vicar of Bray: or, a Paradox in Praise of the Turncoat Clergy’ in Alexander Brome's Athenian Sport: Or two thousand paradoxes (1707).Footnote 53 The time-serving vicar was the subject of a popular ballad. In it, he recalls that he was high church under Charles II, stout in support of the Royal Supremacy and divine right, before opposing both under James II, when ‘The Church of Rome I found would fit / Full well my constitution. / And I had been a Jesuit, / But for the Revolution’. After 1688, he ditched James for William III: ‘Old principles I did revoke, / Set conscience at a distance’, embracing the Whigs until Anne became queen, ‘The Church of England's Glory’, and ‘Another face of things was seen / And I became a Tory’. He was Whig again after 1714, happy to swear loyalty to the Hanoverians for as long as ‘they can keep possession’. The ballad was a farce. Sixty years of religious history were collapsed into the hypocritical code of one cleric: interest over principle. The ballad's refrain jests over and over: ‘And this is law, I will maintain / Unto my Dying Day, Sir. / That whatsoever king may reign / I will be the Vicar of Bray, Sir!’Footnote 54

Other reuses of the Vicar of Bray were more aggressive. Between 1660 and 1720, ‘Vicar of Bray’ was used to insult clergy of all stripes. It exposed the hypocrisy of Nonconformists and moderate Anglicans who supported comprehension or toleration. In his Lord Mayor's sermon of 1682, John Evans sneered at ministers who turned with the times and made the Vicar of Bray ‘the vicar of the day’.Footnote 55 A year later, The Character of A Church-Trimmer raged at hypocrites who loved power, not their church, and backed campaigns for toleration out of political expediency. ‘He resolves to be somebody (and not Vicar of Bray still)’, using Whig politics to graduate to ‘Beelzebub or Prince of TRIMMERS, the Devil of a Saint, and the Monster of a Man, into the bargain; for he is Two-fold all over’.Footnote 56 After 1688, however, the insult was less specific to Nonconformity. The readiness of so many Anglicans to renounce their oaths to James II was condemned as unctuous hypocrisy in texts like Hysteron Proteron. A Sermon lately Preached by the Vicar of Bray (c.1690).Footnote 57 The hypocrisy of William Sherlock, who performed a spectacular volte-face in August 1690, taking oaths to William and Mary having previously been a vociferous nonjuror, was met with dismay: ‘a right Sherlockain will live in every Air, side with every Government, and conform to all sorts of Revolutions [he is] a Harlot [who] resolves to be Vicar of Bray’.Footnote 58 The State Proteus (1690) unpicked Anglican justifications for taking the oaths as sophistry. ‘All honest men’ judged the oath ‘a mean and unworthy Compliance … unbecoming of Ecclesiastical Professours’, the preserve of ‘such Vicars of Bray’ who are ‘well known to be a scandal to their function’ as clergy. There are some truths in Christianity which are beyond qualification, the author noted. Passive obedience was one of them.Footnote 59

The ire of these charges was a long way from Fuller's merry proverb. The Vicar of Bray was a stock joke, and stock jokes are pliable. As a shorthand for clerical hypocrisy, its connotations of self-interest over principle were stable. But its effect varied according to how it was used. The ‘Vicar of Bray’ could be proverbial, the gentle ribbing of a type in order to amuse (after Fuller); or personal, the charging of an individual or group of clergy with hypocrisy in order to condemn. The same joke was a source of mirth in one text, and of invective in the other. Laughing at hypocrisy meant something different in each register. Stock jokes such as ‘trimmers’ and ‘Vicars of Bray’ had a different resonance in the moral panic of 1709–11 because they were charged with the hostility of anti-puritan stereotypes. Stereotypes reduce people to categories: the repetition of stock jokes, familiar images and commonplace language is the root of their power. In religious polemic, those categories were moral: Protestants were good or bad, loyal or disloyal.

The ‘Church in Danger’ campaign pivoted on a binary. Dissenters (and their low church/Whig advocates) were hypocrites, while the high church was sincere; Dissenters sought the ruin of Protestant England, while the high church hoped to protect it.Footnote 60 Those binaries fell into a familiar polemical pattern. The twin ideologies of post-Reformation England – anti-popery and anti-puritanism – were structured around contrary couplings of good and evil, defining ‘true’ Protestants against their anti-Christian others.Footnote 61 The ‘Church in Danger’ campaign was a continuation of anti-puritanism. Its presentation of the dangers of ‘Dissenting’ hypocrisy, fanaticism and zeal in the early eighteenth century echoed Restoration Anglicanism's condemnation of the danger of ‘Nonconformist’ hypocrisy, fanaticism and zeal, which in turn echoed conformist Protestant damning of ‘puritan’ hypocrisy, fanaticism and zeal as a danger to the Elizabethan and Jacobean state. In each case, a true Protestant ‘us’ defined itself by describing a false Protestant ‘them’, with mockery and stereotypes used as the means of demarcation. In reusing old jokes, The Turncoats dressed current concerns about the prominence of Dissent in the familiar clothes of the ‘puritan’ stereotype that stretched back to the 1580s, in what amounted to a crude historical logic: they have always been like this.Footnote 62 Old images expressed current fears with new potency.

Settling Scores

But not all the print's ridicule was so conventional or loud. The Turncoat's verses were subtle and allusive, ridiculing hypocrisy more cuttingly than the blunt crudities of anti-puritan stereotypes. The verses extended the image's ridicule of the Dissenters by accusing them of priestcraft, the practice of fraud, deceit and superstition behind which clergy throughout history had supposedly hidden their sinister pursuit of wealth and power. These charges had been levelled at the established church since the 1690s, a decade in which, Burnet recalled, ‘priestcraft grew to become another word in fashion’ and ‘it became a common topic of discourse to treat all mysteries in religion as the contrivances of priests, to bring the world into a blind submission to them’.Footnote 63 The critique was part of a broader intellectual culture that subjected religion to reason to strip away superstition, leaving a primitive faith with a minimal creed, a Christianity spare in mystery.Footnote 64 This was an extended attack on Anglican authority, and it fuelled the ‘Church in Danger’ panic that feared that toleration, freethought and Dissent threatened to undermine the Protestant interest.Footnote 65 Freethinkers criticized the Church of England's doctrine, questioned the legitimacy of its political power, and challenged the scriptural basis of its claim to be an heir of the early church. They argued that the bases of clerical authority – doctrine, ritual, ordination and episcopacy – were not inherent in Scripture, but were the fabrications of priests who had slowly corrupted Christianity over the previous millennium, inventing superstitions in the interests of power and gain, and persecuting and censoring those who challenged their monopoly on the sacred. In this, the Anglican church was a sibling of Rome. The charge of priestcraft extended the core tenets of anti-popery to assault the tyranny of all established churches, not just the papal church.Footnote 66 The continued dominance of the established church and its attempts to curtail the role of Dissenters in English politics and society despite the comprehensive vision of the Protestant interest outlined in the 1688–9 Revolution were the latest examples of priestcraft at work.

The Turncoats' verses turned these charges of priestcraft on their head. The recent conversions showed that it was the Dissenters and their allies, the false brethren in the low church, who were guilty of priestcraft, self-interested hypocrites who wore principles lightly to mask their hunger for gain. The print mocked the Dissenters with their own language, undermining that language in the process. This was ridicule that cut to the quick, settling scores built up over twenty years of hostility.

This inversion was not immediately apparent. The verses gulled readers, appearing to relay a conventional account of priestcraft's slow ruination of Christianity as described by radicals like Charles Blount, John Dennis and Matthew Tindal.Footnote 67 Priestcraft Expos'd (1691), for example, depicted all priests as con men who abused religion, muddying faith with mystery to cast the world under their authority.Footnote 68 The Turncoats aped the language of these histories of priestcraft. Religion was ‘Form'd by Heaven, to cultivate Mankind’. Originally, it had been pure, ‘Its Rules were easy, and its Precepts plain; | Its Voteries not link'd to Sordid gain’, but was corrupted by priests ‘when Interest sway'd, | And men, too much, the love of Gold obey'd’, selling superstition and conning the laity to buy a place in heaven rather than living by faith. Hypocrisy was the root cause of priestly corruption. History showed that priests changed their principles with the prevailing wind, ‘And rather than they'd lose a Benefice, | They'd be of Several Notions in a Trice’, sullying religion with politics and interest.

This conspiracy was alive in the present: ‘Thus, now a days, tis plainely so we find, | Int'rest still rules and governs all mankind’. But where accounts of priestcraft pointed to the established church (particularly its jure divino claims to authority), the print targeted Dissent:

Principles were abandoned for profit. When presented with a rich benefice, the Dissenters no longer saw the established church as popish, or the Book of Common Prayer as idolatrous. One (former) Dissenter was singled out:

Samuel Palmer, the former Presbyterian minister at Gravel Lane, Southwark, had taken orders in the established church in 1709. Parker's conformity was shocking. During the occasional conformity debates of 1703–4, he had been a public champion of Dissent, an advocate of the Dissenting academies attacked by an Anglican hierarchy keen to portray them as seditious conventicles. Palmer's hypocrisy galled because of its self-interest. He was suspected of seeking preferment in the church because he felt undervalued by the Dissenting hierarchy.Footnote 71 The Turncoats held him up for shame: this was the sort of man who was infiltrating the established church.

The ‘Anglican’ conversions during the Tory-turn of 1710–11 exposed Dissenters as agents of the priestcraft they decried in others. By inverting the language of priestcraft, the verses underscored the sincerity of the high church party, alluding to Sacheverell in its praise for the few ‘Pious, Good and Just’ priests who were ‘True to their God, Religion, and their Trust’. However, there was no absolute Anglican (sincere)/Dissenter (hypocrite) binary here. Mockery of Palmer bled into broader swathes of ridicule. Dissent was not uniquely crooked:

These hypocrites, the verses implied, were the majority. This was an indictment of the low churchmen who had supported toleration, Dissent and (in the eyes of high churchmen) encouraged and cultivated the freethought that threatened the church. Such men had exposed their true natures in 1688, breaking their oaths to James II to maintain preferment in the established church: ‘The Priests that always Right Divine do boast, | Usually turn'd to what was Uppermost.’Footnote 73 But the indictment of hypocrisy went further. Charles Leslie – Tory, nonjuror and ally of Sacheverell – was damned as an arch-hypocrite who ‘best can tell’ where gain could be found. Leslie had a two-decade track record of vehement opposition to Dissent and the ideological foundations of the post-revolutionary regime (and had engaged in heated polemical exchanges about occasional conformity and passive obedience). Why would a pro-Tory, anti-Dissent print mock a man who was both of those things? In 1710, Leslie's extreme views on the Hanoverian succession (Burnet described him as ‘the violentest Jacobite in the nation’) led him to sever ties with Sacheverell and the Tories. Outlawed, he fled in 1711 to the Jacobite court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, just outside Paris, where he advocated for an invasion.Footnote 74 Leslie, the print mocked, had turned coat on his own country.

The tone of the ridicule here was uncertain. The Turncoats was unquestionably part of an anti-Dissent and pro-high church/Sacheverell polemic that celebrated the Tory ascendency of 1710–11. At the same time, the lampooning of hypocrites here was not straightforwardly the us/them of party politics. Because the cast of hypocrites ridiculed was broader than those party boundaries, the print conveyed the impression that religious hypocrisy was pervasive in late Stuart society. The Turncoats was ambiguous: it was hostile to Dissent, but not solidly in support of the established church; it celebrated the Tory-high church victory of 1710–11, but worried that the hypocrisy of self-interested, turncoat clergy of many stripes threatened Protestant England despite that victory. This ambiguity responded to fears about religious hypocrisy in the early eighteenth century.

Those fears centred on public figures routinely dissimulating in matters of faith and thereby turning religion into a plaything of party politics. As Knights has shown, accusations of religion being used to cloak self- or party-interest became a normal part of politics. Whig and Tory, and churchmen high and low, competed to define themselves as sincere and moderate by painting their opponents as zealous hypocrites. This competition reached its apogee during the occasional conformity debates. High churchmen accused Dissenters of hypocrisy, but were in turn accused of adopting religious positions for party interests. Hypocrites were now celebrated ‘under the name of a Church-Man’, claimed the Naked Truth of Phanaticism Detected (1705), the ‘high’ label being merely the ‘specious pretence of the Church’ to win ‘places of trust and authority’ and bring down the government.Footnote 75 Faults on Both Sides (1710) saw the occasional conformity bills as cynical Tory devices designed to ‘disable’ Dissenters from voting Whig in the elections.Footnote 76 This saturation of the public sphere with a promiscuous use of images of hypocrisy was unnerving: ‘the claims and counter-claims of hypocrisy and sincerity around the Occasional Conformity Bills reflected a perception that interest rather than conscience prevailed’ in religion and that this threatened the public good.Footnote 77 The Turncoats’ ridicule responded to those anxieties.

Laughter

Ridicule expressed contempt: ridiculing someone or something was a public indictment of their worth. ‘Affectation’, claimed Henry Fielding in 1741, is ‘the only source of the true Ridiculous’. Vanity and hypocrisy were the worst affectations. Hypocrisy was the more ridiculous of the two because the gap between the hypocrite's inner and outer lives was greater, and therefore more contemptible, the hypocrite ‘endeavours to avoid Censure by concealing vices under an Appearance of their opposite Virtues’.Footnote 78 Ridicule exposed those vices, shaming the hypocrite by subjecting them to derisive laughter. Ridicule was potent because it diminished its object.Footnote 79 ‘They which wittely can … use a nippyng taunte, shalbee able to abolishe a ryghte worthy man’, noted Thomas Wilson, and ‘no marvaile: for when ye iest is aptly applied, the hearers laugh immediately & who would gladly be laughed to scorn’.Footnote 80 The potency of ridicule was seen in satire, which its authors claimed could shame offenders into reforming their vices; in the rough justice with which communities humiliated the shrews, cuckolds and other transgressors of the patriarchal codes that bound them together;Footnote 81 and in the use of derogatory libels in popular politics, the unseemly rhymes with which ordinary people protested against authority.Footnote 82

The potency of laughter disturbed early modern society. Caution was urged over who and what should be exposed to contempt. Laughing at religion itself (as opposed to its hypocritical practitioners) was condemned as a path to atheism.Footnote 83 Rough laughter was also concerning because it could undermine authority and cause enmity and division. Satirists drew distinctions between their refined ridicule and the hacking raillery of lowly, immoderate mockery that sat uncomfortably with polite ideals.Footnote 84 Those ideals did not blunt the appeal of impolite laughter, however, which was a cruel and ever-present feature of eighteenth-century popular culture, as Simon Dickie and Vic Gatrell have shown in detail.Footnote 85 Early modern people were unnerved by laughter because they were uncertain about whether its causes were benign or malign. Was it a mark of good fellowship or malice?Footnote 86 That uncertainty was reflected in the words they used to describe laughter, which conveyed both mirth and malice. Laughter could be a ‘jesting’ or a ‘scoffing’, ‘bantering’ or ‘taunting’.

That uncertainty is present in modern theories of laughter, which fall into three categories: incongruity, superiority and relief.Footnote 87 Incongruity theories propose that we laugh when something surprises us. Laughter expresses delight at our expectations being subverted. Wordplay, innuendo and absurdities are obvious examples and were described as sources of mirth in Henry Peacham's Garden of Eloquence (1577).Footnote 88 Frances Hutchinson discussed laughter in terms of incongruity, presenting it as an expression of wonder at novelty.Footnote 89 Where incongruity theories see laughter as benevolent, a good-natured source of pleasure, superiority theories stress its roots in malice and aggression. This understanding, articulated most fully by Thomas Hobbes, claims that laughter expresses the ‘sudden glory’ we feel in perceiving ourselves superior to a person, action or object. It dates from ancient Greece and Rome.Footnote 90 Plato described laughter as a malicious joy taken in others’ misfortunes; Aristotle noted that we laugh at what is contemptible; and Quintilian characterized it as derisive and capable of diminishing an opponent.Footnote 91 Laughter of this sort was used in sermons to convey the superiority of one religious faction over another, to level scorn at stereotypes in jestbooks and plays, and to bind communities together against perceived others.Footnote 92

Relief theories present laughter as a release of pent-up mental and physical tensions. Laughter's reviving properties were widely noted in early modern Europe. In 1553, Wilson claimed that by laughing the mind ‘be refreshed, and find some sweete delite’.Footnote 93 His views were echoed five years later in Nicholas Udall's claim that ‘mirth prolongeth life, and causeth health’.Footnote 94 The medicinal nature of laughter was considered most thoroughly in Laurent Joubert's Traité du ris (1579), which provided many examples of the physical sensations of laughter as a cure for melancholy and a purgative for the body. These views were shared by other medical commentary on the subject.Footnote 95 That commentary saw laughter as a problematic phenomenon, a contrary expression of joy and misery. Timothy Bright's Treatise of Melancholy (1586) considered that contradiction head on in the chapter ‘Why and how one weepeth for joy, and laugheth for grief’. The answer, Bright explained, lay in nature's fecundity. If the sun's heat can make wax soft but clay hard, why should sorrow not elicit tears and laughter?Footnote 96 For Joubert, because we laugh at what is ugly, laughter must ultimately relate to misery. Medical writing presented the physical effects of laughter as a reflex to tensions caused by the clash of joy and misery, shaking strains out of the mind and body.

Incongruity, superiority and relief are seen as competing theories weighed against each other to find the ‘best’ explanation of laughter. It is more useful to see them as complementary, with aspects of all three present in each instance of laughter. This rings true for ridicule: we laugh at being surprised by a witty conceit (incongruity) that expresses scorn at what is mocked (superiority), which in turn releases pent-up hostility towards that object (relief). We see this combination in The Turncoats. The print's ridiculous image is incongruous (conscience worn as lightly as clothes); its mockery was superior and directed anger and contempt at hypocrites (who were laughed to scorn); and by providing its viewers with an outlet for those hostile emotions, the laughter it elicited relieved. There were plenty of anxieties to relieve during 1709–11, when the pervasiveness of hypocrisy in public life had caused a collapse of trust in politics. The Turncoats’ uncertain ridicule spoke to those fears, expressing joy that the Tory-high church had triumphed over the Dissenters and low churchmen it mocked, and anguish at the fact that the hypocrisy it exposed continued to threaten the church. That anguish is expressed by the only character in the print who does not jest. Horrified by the hypocrisy they witness in the tailor's shop, the labourer on the far right evokes Sacheverell in the hope he can save them: ‘I'll go to St Mary Overy's and pray for the Doctor’.Footnote 97 The Tories had won, but the church was still in danger.

Conclusion

That prints like The Turncoats were ephemeral does not mean that they were unsophisticated. The satire's witty conceit told old jokes in new ways, using laughter as a weapon at a moment of political change. Its ridicule was both a product of and a response to a defining problem of that moment: hypocrisy. Ridicule appealed because it evoked moral emotions such as anger and contempt, deriding the worth of one group (Dissenters/low church) to assert the superiority of another (high church/Tories). It also unnerved. Exposing hypocrisy ultimately served to highlight its existence as a real and present danger to eighteenth-century society. It has been argued that much lay behind laughter. The Turncoats built on older traditions and stereotypes, twisting anti-popery, anti-puritanism and the language of priestcraft to the polemical purposes of the present. Familiarity ensured that the thrust of the print's anti-Dissenter and pro-Sacheverell mockery was intelligible to even those with only a cursory grasp of politics, while asides to Leslie, Palmer and priestcraft appealed to the more informed, the knowing viewers who could appreciate the closeness of the mockery. Graphic satires did not simplify or reduce debates. They were not secondary sources of politics, synopses of opinion developed elsewhere in political discourse, but sophisticated pieces of political commentary in their own right.Footnote 98