Introduction

Legal discrimination against women in economic opportunities is still pervasive in the world. For instance, many countries have laws restricting women’s mobility or preventing a woman from being the head of household. Furthermore, women in many countries experience unequal treatments in labor markets and in access to credit, property ownership, and inheritance. According to the Women, Business, and the Law (WBL) databaseFootnote 1 constructed by the World Bank, only eight countries in the world have no legal discrimination against women in economic opportunities (Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020).Footnote 2 Unequal treatment of women under the law poses a significant barrier to women who plan to work or start a business (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Jensenius and Nelson-Nuñez2019; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020). Restrictions on women’s employment, access to property rights, and entrepreneurial activity weaken their bargaining power at home and their political influence, which undermines gender equality.

While legal gender equality of economic opportunity has globally improved over time, progress varies across countries. Why are some countries slower than others to reform gender-discriminatory laws? Many studies focus on structural variables, such as economic development (Doepke et al., Reference Doepke, Tertilt and Voena2012), technological change (Geddes and Lueck, Reference Geddes and Lueck2002; Doepke and Tertilt, Reference Doepke and Tertilt2009), and cultural changes (Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2003). These variables influence legal gender equality by affecting politicians and voters’ incentives or attitudes. However, while these are significant structural factors that shape legal gender equality of economic opportunity, they are insufficient to produce equal treatment of men and women under the law. Political actions are necessary to reform gender-based discrimination and achieve legal gender equality.

Who drives the political actions necessary to remove legal barriers to women’s employment and entrepreneurial activity? According to many existing political economy models, the personal characteristics of policymakers, including gender, do not matter (Hessami and da Fonseca, Reference Hessami and da Fonseca2020). For example, according to the well-known median voter theory (Downs, Reference Downs1957), if the unequal treatment of women in economic opportunities is salient to many female voters, parties will address it in an attempt to increase their vote share. However, many studies provide evidence to the contrary, finding that the personal characteristics of politicians do matter. Politicians cannot credibly commit to their campaign promises since they have their own preferences over policy outcomes (Besley and Coate, Reference Besley and Coate1997). In particular, extant scholarship on gender and politics demonstrates that men and women have different policy preferences (Shapiro and Mahajan, Reference Shapiro and Mahajan1986) and that female policymakers are more likely to emphasize women’s issues and adopt women-friendly policies (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004; Childs, Reference Childs2004; Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). This implies that political reforms favoring legal gender equality are more likely to occur where more women occupy decision-making positions in politics.

This correlation, while compelling, has not yet been examined from a global perspective. Despite the strong theoretical case for doing so, only a few studies investigate the effect of female political representation on legal gender discrimination, instead, examining policies related to the legal gender equality of economic opportunity in specific contexts (Atchison and Down, Reference Atchison and Down2009; Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2008; Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018; Brulé, Reference Brulé2020). Additionally, we know neither whether types of women’s descriptive representation matter nor under what conditions female legislators and/or ministers affect legal gender equality of economic opportunity.

This article explores comprehensively and systematically the relationship between women’s descriptive representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Building on existing studies of women’s descriptive and substantive representation, we argue that as the proportion of women in political positions increases, legal gender equality of economic opportunity improves. We further posit that gains in female legislative representation are more likely to translate into improved legal gender equality than those in female cabinet representation when either legislative power is stronger or the level of democracy is higher. The link between women’s legislative representation and legal gender equality requires legislatures with strong agenda-setting and policy-making power. Thus, female legislators are more effective than female ministers when the legislature’s law-making powers are strong, but the opposite is true when those powers are weak. Similarly, the level of democracy shapes the effect of female legislative representation since democratic countries tend to have stronger legislatures while authoritarian countries concentrate more policy-making power into the executive. We thus hypothesize that female legislators are more influential than female cabinet ministers as the level of democracy increases.

To test these arguments, we focus on legal discrimination that a woman may face from the time she enters the workforce to her retirement. We draw on the WBL database that provides cross-national information on legal discrimination against women in economic opportunities. Looking at 156 countries from 1970 to 2014, we find that the percentages of both female legislators and female ministers are positively associated with legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Importantly, each female representation has its own independent effect on legal gender equality. This finding is robust to attempts to rule out competing explanations, alternative estimation methods, alternative temporal units of analysis, and alternative samples. We also find that when the legislature’s law-making power is higher, the effect of female legislative members is greater than that of female cabinet members. Similarly, the level of democracy reinforces the effect of female legislators, not the effect of female cabinet ministers. Consistent with these findings, our supplementary analyses reveal that gender quotas are positively associated with legal gender equality and are more effective when the levels of democracy or legislative power are high.

This article contributes to the literature on women’s descriptive and substantive representation by revealing that women’s under-representation in political positions is an important background condition for the unequal treatment of women in economic opportunities. It presents systematic evidence that an increased presence of women in the legislature or cabinet is associated with legislation outlawing discrimination against women in economic opportunities. Even before economic development takes hold, the political empowerment of women improves legal gender equality in developing or least-developed countries. Next, this study contributes to the understanding of how and when women policymakers matter by highlighting the role of contexts under which one type of women’s descriptive representation is more effective than the other. Both female legislators and cabinet ministers face institutional or political contexts that can reinforce or hinder their efforts to reduce the legal gender gap. This article shows that the effects of female legislators and ministers and their relative influence are conditional on the legislature’s law-making power and the level of democracy.

Women’s representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity

Existing scholarship provides several reasons why an increase in the descriptive representation of women produces a decrease in legal gender discrimination in economic opportunities. First, men and women differ in policy priorities. Researchers have proposed that gender differences in policy preferences exist either because women intrinsically care more about issues, such as children, family, and public health, or because women face different socio-economic conditions than men (Doepke et al., Reference Doepke, Tertilt and Voena2012). Studies show that women care more about issues related to women, children, family, gender equality, and the environment (Shapiro and Mahajan, Reference Shapiro and Mahajan1986; Inglehart and Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2003). Gender differences in policy preferences are also found among public officials and politicians. Female legislators are more likely to emphasize social policy issues, gender equality, and environmental issues (Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). Additionally, female politicians and policymakers are more likely than male counterparts to see female voters as an important constituent group. For example, female politicians are more likely to consider women as an important constituency, compared to male politicians, and speak directly on behalf of their women constituents’ well-being (Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). They also tend to pay attention to gender issues and defend feminist ideas (Childs, Reference Childs2004).

These two facts suggest that an increase in women’s descriptive representation will lead to improvements in women’s substantive representation, as both process and outcome (Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008: 398). A great deal of studies support this expectation. First, several studies show that female legislators are more likely to propose and vote for bills related to ‘women’s issues’ such as gender equality, education, children’s issues, health care, and welfare (Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006; Franceschet and Piscopo, Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). Other studies find that when more women are represented in the legislature, policy changes occur in the direction of women’s preferences. A proportion of women in the national legislatures or local councils is positively correlated with spending on childcare, education, health, and welfare (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004) as well as female-friendly policies, such as maternity and childcare leave policies (Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2008). Moreover, women’s legislative representation is positively associated with infant and child survival in developing countries (Mechkova and Carlitz, Reference Mechkova and Carlitz2021). In sum, these findings demonstrate that a growth in women’s descriptive representation translates into improvements in women’s substantive representation.

Accordingly, there are good reasons to expect that as more women enter important policy-making positions, the legal equality between men and women in economic opportunities is likely to improve. Female policymakers pay more attention than male counterparts to legal restrictions on women’s economic autonomy because the ability for women to make independent economic decisions is critical to gender equality and women’s empowerment, and legal discrimination undermines this ability. Women’s employment and asset ownership shape their bargaining position at home, which affects outcomes important to women, such as economic and physical security and personal fulfillment (Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, McGuire, Rosenbluth and Yamagishi2018). When women are employed and/or own more assets, they are more likely to participate in household decision-making and better able to make independent decisions. Female labor market participation also has long-term implications since it encourages parents to invest in the education of their daughters and to have higher aspirations for them (Duflo, Reference Duflo2012: 1056–1057). Expanding the opportunities available to women in the labor market can serve to improve gender equality in politics in the long run (Ross, Reference Ross2008).

Furthermore, legal gender discrimination negatively affects economic outcomes for women by reducing female labor market participation and asset ownership and maintaining or increasing wage gender gaps (Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales, Jain-Chandra, Kochhar and Newiak2015; Htun et al., Reference Htun, Jensenius and Nelson-Nuñez2019; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020). Therefore, reforming gender-discriminatory laws will expand opportunities available to women and encourage more female participation in the formal economy. This implies that to the extent to which female policymakers consider women’s economic empowerment an important issue, they pay greater attention to legal gender discrimination and make more efforts to eliminate it. We can expect that an increase in women’s descriptive representation leads to an improvement in legal gender equality of economic opportunity.

Only a few studies investigate the effect of female political representation on specific policies related to legal gender equality. Kittilson (Reference Kittilson2008) presents cross-national evidence that the percentage of female legislators is positively correlated with the likelihood of adopting maternity and childcare leave policies and a broadening of the scope of these policies in 19 OECD democracies. Similarly, Atchison and Down (Reference Atchison and Down2009) find that the percentage of female cabinet members is positively correlated with the total weeks of maternity and parental leave guaranteed by the state in 18 advanced democracies. Despite these studies’ contributions, the relationship between women’s descriptive representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity must be examined comprehensively and systematically in a global context. Thus, we test the following hypothesis:

H1: The higher the share of women in parliaments and in cabinets, the higher the legal gender equality of economic opportunity.

The role of context and types of political power

Even though women in politics can make a difference to legal gender equality of economic opportunity, we need to understand under what conditions female legislators and/or ministers affect legal gender equality of economic opportunity and which type of women’s descriptive representation is more effective in improving legal gender equality. Most existing studies tend to focus on women’s legislative representation. This is not surprising, given the crucial position of the legislature in representative democracies. Law-making is among the key functions of national legislatures. Legislatures represent constituent preferences, set policy agendas, propose bills, debate and amend proposed bills, pass bills, and monitor policy implementations. Furthermore, legislatures exercise not only positive but also negative agenda-setting power by blocking certain policy initiatives. Thus, increasing the proportion of women in national legislatures can help to eliminate legal gender discrimination.

However, the role of legislatures in the law-making process substantially varies across countries (Fish and Kroenig, Reference Fish and Kroenig2009; Wilson and Woldense, Reference Wilson and Woldense2019). As Schwindt-Bayer and Squire (Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Squire2014) conceptualize, the legislature’s policy-making power consists of ‘institutional policy power’ and ‘personal professional power’. Institutional policy power refers to the constitutional and institutional powers of the legislature as an organizational entity, in the policy-making process. This power comes from the country’s constitutional or legislative rules and norms about the legislature’s power and responsibilities in relation to other government branches. Personal professional power refers to the influence of individual legislators on the policy-making process. Factors such as the frequency of legislative sessions and resources available for individual legislators affect personal professional power. These two powers vary considerably across countries (Fish and Kroenig, Reference Fish and Kroenig2009; Opalo, Reference Opalo2019; Wilson and Woldense, Reference Wilson and Woldense2019).

In the US context, it makes sense to emphasize female legislative representation since the US Congress plays a critical role in the policy-making process. Under the separation of powers, the Congress enjoys constitutionally-assigned legislative authority to initiate and adopt bills. It is also equipped with specialized permanent committees that have specific policy jurisdictions and the organizational, financial, and human resources required for effective policy-making. Thus, the Congress has both strong institutional policy power and strong personal professional power, allowing it to play a leading role in the policy-making process. Conversely, the executive’s influence over policies mainly arises from the veto power and control over the bureaucracy, although the president can issue administrative directives, such as decrees and executive orders.

However, in many other contexts, few legislatures play such a major role in the policy-making process (Mezey, Reference Mezey1983). For instance, in parliamentary democracies, the cabinet rather than the legislature sets policy agendas and formulates and oversees policies (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). ‘Each cabinet minister can call on a considerable pool of expertise in his or her own department, expertise that is professionally focused in a very intense manner on the policy concerns of the department. Government departments are the only organizations with the resources to generate fully developed policy proposals and the expertise to implement and monitor any proposal that might be selected’. (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996: 30). As department heads, thus, cabinet ministers enjoy a dominant advantage in drafting legislation. According to Saiegh (Reference Saiegh2014: 484), government-sponsored bills account for at least 70% of the bills presented to the legislature in parliamentary democracies, and 80% of these government-sponsored bills become laws.

Even in many presidential democracies outside the US, the executive rather than the legislature is often the most important player in the formulation and implementation of policy. In Latin America, policy-making power is usually concentrated in the hands of the executive since many constitutions invest the executive with the authority to issue unilaterally executive decrees or orders (Saiegh, Reference Saiegh2010). In Africa often characterized by ‘big man’ rule, the executive dominates the legislature and easily secures legislative approval of its policies by utilizing formal agenda-setting powers and informal powers to cultivate patron-client networks (Chaisty et al., Reference Chaisty, Cheeseman and Power2014). Moreover, most presidential democracies are developing countries where legislatures tend to lack financial resources and staff members with policy expertise. Thus, they are often limited in the both dimensions of institutional policy power and personal professional power.

Last, the same is true of authoritarian regimes. Many studies demonstrate that authoritarian legislatures facilitate power-sharing, help to coopt opposition members, and identify popular discontent (Brancati, Reference Brancati2014). Even so, though varying in the legislative capabilities, most authoritarian legislatures do not have the ability to introduce bills and determine policy contents (Wilson and Woldense, Reference Wilson and Woldense2019). Brancati (Reference Brancati2014) claims that ‘because authoritarian legislatures exist at the discretion of the dictator, they do not have real decision-making power and only rubber-stamp government-proposed legislation’ (p. 317).

This implies that the influence of legislatures relative to cabinets in the policy-making process substantially varies across regions and countries. Then, an exclusive focus on the proportion of female legislators is misguided. Under certain political or institutional contexts, female ministers are better positioned than female legislators to initiate policy changes for gender equality and to promote female-friendly agendas (Atchison and Down, Reference Atchison and Down2009; Stockemer and Sundström, Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018). If the executive plays a more important role in policy formulation and implementation than the legislature, women’s inclusion in the cabinet will be more effective in producing legal reforms for legal gender equality.

Meanwhile, a government type does not simply determine the influence of legislatures relative to cabinets. As discussed above, the executive rather than the legislature is often the most important policy-making player in many presidential democracies outside the United States. Even in African presidential systems where legislatures are believed to be generally weak, considerable variations in legislative strength and institutionalization exist (Opalo, Reference Opalo2019). Similarly, even though the government usually sets policy agendas and formulates policies in parliamentary democracies, the government with minority legislative support needs to seek legislative consensus, which increases the involvement of legislators in the process of policy formulation (Arter, Reference Arter2006). Last, even though legislatures do not play proactive roles in the policy-making process, they may influence that process by debating, delaying, opposing, or amending government policies (Saiegh, Reference Saiegh2010).

Thus, it is necessary to formulate conditional expectation about the influence of women’s descriptive representation on legal gender equality. We hypothesize that when the legislature’s institutional policy power is greater and/or individual legislators have more personal professional power, the legislature exerts greater influence on policy. For example, if the legislature can propose bills in all policy areas, or its approval is required to pass legislation, its law-making power is greater. Similarly, when the legislature is equipped with a functioning committee system or staff members with policy expertise, legislators are better able to craft public policy and can be more professionalized (Schwindt-Bayer and Squire, Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Squire2014: 627–628). These institutional policy and personal professional powers in turn increase the effect of female legislators on legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Contrarily, the influence of female ministers on legal gender equality has little relevance to the legislature’s law-making power. If anything, the presence of female ministers may negatively interact with legislative effectiveness since the cabinet’s law-making power declines when the legislature’s law-making power is stronger. Accordingly, female legislative representation will be more effective than female cabinet representation in reforming legal discrimination against women when the legislature’s law-making power is high, and vice versa.

Similarly, a country’s political system can structure the effect of women’s descriptive representation since it is related to the legislature’s law-making power. For example, Wilson and Woldense (Reference Wilson and Woldense2019) show that the level of democracy is strongly associated with overall legislative powers. Palanza et al. (Reference Palanza, Scartascini and Tommasi2016) find that the age of democracy is positively associated with the degree of the legislature’s institutionalization. If a country is more democratic, the legislature’s agenda-setting power is likely to be higher, and female legislators are better able to pursue legislative reforms for gender equality. Thus, we can expect that as the level of democracy increases, the effect of female legislators on legal gender equality increases.

Contrarily, the interaction between democracy level and female ministers is not straightforward. As a country is more autocratic, more policy-making power is concentrated into the executive, which makes female ministers more effective in addressing legal discrimination against women. At the same time, female ministers may be better able to pursue women-friendly policies in more democratic countries. Given the conflicting effects, we expect that the magnitude of the interaction between female minister and democracy will be smaller than that of the interaction between female legislators and democracy. This suggests that female legislators are more effective than female ministers in improving legal gender equality when the level of democracy is high. This discussion leads to the following two testable hypotheses:

H2: Female legislators are more effective than female ministers in improving legal gender equality when the legislature’s law-making power is higher.

H3: Female legislators are more effective than female ministers in improving legal gender equality when the democracy level is higher.

Data and method

To test our hypotheses, we construct a time-series cross-sectional dataset covering a maximum of 156 countries from 1970 to 2014. Our unit of analysis is the country-year.

Our dependent variable is the degree of legal gender equality of economic opportunity. To measure it, we draw on the WBL index taken from the World Bank’s WBL database. The WBL database examines laws and regulations that affect women’s economic participation and opportunity and evaluate whether laws treat men and women equally. World Bank legal experts collaborate with local experts, including lawyers, judges, civil society representatives, and public officials in collecting information on the legal environment in each country. They examine 35 individual legislative issues under 8 indicators: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions. Footnote 3 For each indicator, they assign a score, scaled from 0 to 100, by calculating the unweighted average of the four or five binary questions within each indicator. The overall WBL index score is an unweighted average of the eight indicators. Thus, the highest possible value of the index is 100, indicating no legal discrimination against women in the 8 areas related to workforce. For example, a score of 50 implies that women face legal inequality in the half of the 8 areas.

This index has several advantages. Footnote 4 First, the WBL index measures de jure discrimination against women in the workforce since it does not consider the implementation of the law. As pointed out by Hyland et al. (Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020), the legislative context of a given country provides an objective and comparable measure of the legal environment in which women live and work. If women’s descriptive representation influences women’s economic empowerment, its effect is likely to manifest itself first in the improvement of the legal environments. Second, the WBL index is positively associated with equal labor market outcomes. Hyland et al. (Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020) show that it correlates with an increased female labor force participation and a decreased wage gap between men and women (see also Htun et al. (Reference Htun, Jensenius and Nelson-Nuñez2019)). These results mitigate the potential concern that the focus on legal equality may not capture actual gender equality. Last, this index is useful because of its broad scope. The WBL index covers 190 countries from 1970 to 2019, which is well-suited for the purpose of this research. Table 1 shows not only a significant progress in legal gender equality but also variations across countries in the legal equality of economic opportunity between men and women (see also Figure B2 in the supporting online appendix).

Table 1. Descriptive look at gender equality of economic opportunity and women’s descriptive representation. Between SD refers to the standard deviation of the country means, while within SD refers to the average within-country standard deviation

To measure women’s descriptive representation, we focus on the proportion of women in national legislatures and cabinet positions. We obtain the percentage of seats held by women in the lower or single house of each country’s national legislature from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem, version 10) data (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn and Hicken2020). For information on the share of female cabinet members, we rely on the WhoGov dataset (Nyrup and Bramwell, Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020) that contains information on cabinet members between 1966 and 2016 in all countries with a population of more than 400,000. Footnote 5

We need a measure of legislative power that measures the policy-making authority assigned to the legislature, since we hypothesize that legislative power conditions the effect of female legislative representation on the equality of economic opportunity under the law. To this end, we use six variables from the V-Dem data and aggregate them to create the index of legislative powers. The first two variables focus on the legislature’s law-making influence. Legislates by law denotes whether the legislature can introduce bills in all policy jurisdictions by law, while Legislates in practice indicates whether its approval is required to pass legislation. The next three variables capture the institutional resources of the legislature: Legislature committees focuses on whether the legislature has a functioning committee system; Legislature resources looks at whether the legislature controls the resources to finance its own internal operations; and Legislative staff focuses on whether the legislature has at least one staff member with policy expertise. The last variable, % of elected legislators, measures the percentage of legislators directly elected in popular elections. We standardize all six variables and average them. Footnote 6 A higher value indicates greater legislative power.

We control for potential confounding variables that can affect women’s political representation as well as legal equality of economic opportunity for women. First, we include two economic variables that correlate with concerns for gender equality: a log of GDP per capita and a log of oil rents per capita, measured as a country’s total rents from oil and gas divided by its population. We expect that the former will correlate with a higher demand for gender equality in the economic sphere (Geddes and Lueck, Reference Geddes and Lueck2002; Fernández, Reference Fernández2014), while the latter will be negatively associated with it (Ross, Reference Ross2008). Second, as the level of democracy is higher, women are better able to mobilize for legal gender equality and women’s inclusion in office, and thus both the legal equality of economic opportunity for women and women’s political representation may improve. We include the electoral democracy index from the V-Dem data. Footnote 7 Third, we include the dummy for communist regimes. Communist countries tend to have lower legal barriers to encourage women’s participation in the workforce as well as to constrain the influence of religion (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020). Last, we include country fixed effects to control for time-invariant country characteristics, such as culture, colonial history, or geography, that influence social preferences for gender equity, and linear time trends to capture upward trends in the data series of women’s descriptive representation and the WBL index.

Results

Before turning to the multivariate analysis, we take a preliminary look at the data. The left panel of Figure 1 plots changes in the WBL index for each country between 1970 and 2019 against the change in the percentage of female legislators over the same period and displays a positive relationship between changes in female legislative representation and changes in gender equality of economic opportunity. A similar pattern emerges when we use the share of female cabinet members instead of that of female legislators for the period of 1970–2016. These results provide suggestive evidence that women’s descriptive representation contributes to legal gender equality of economic opportunity.

Figure 1. Change in WBL index and women’s political representation.

Table 2 presents the fixed effects OLS regression estimates. We calculate robust standard errors clustered by country. The first two models focus on the percentage of female legislators; the next two models use the percentage of female cabinet members; and the last two models include both variables. For each variable, we adopt two different model specifications. One model specification is the minimal specification that only includes time trend variables and country fixed effects, while the other specification includes the full baseline controls.

Table 2. Women’s descriptive representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity (FE estimates). All models include country fixed effects. Robust standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. All explanatory variables are lagged

*

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

, **

$p \lt 0.1$

, **

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

, ***

$p \lt 0.05$

, ***

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

.

$p \lt 0.01$

.

The results are consistent with H1: Both the percentage of female legislators and that of female cabinet members are correlated with an increased level of the WBL index. Both the coefficient estimates on female legislators and female cabinet members are statistically significant at the 1% level, regardless of whether we include other control variables or not. Column 2 shows that conditional on country fixed effects and other control variables, a one within-country standard deviation increase in the share of female legislators (

![]() $ \approx 8.14$

) is associated with an increase of about 3.03 in the WBL index. According to Column 4, the corresponding shift in the share of female cabinet members (

$ \approx 8.14$

) is associated with an increase of about 3.03 in the WBL index. According to Column 4, the corresponding shift in the share of female cabinet members (

![]() $ \approx 8.43$

) is associated with an increase of 2.17 in the WBL index. Even when we include both measures of female political representation, both variables are positively associated with the WBL index, although their magnitude slightly decreases. The effect of female legislators is greater in magnitude than that of female ministers, but the difference is statistically significant at the 5% level.

$ \approx 8.43$

) is associated with an increase of 2.17 in the WBL index. Even when we include both measures of female political representation, both variables are positively associated with the WBL index, although their magnitude slightly decreases. The effect of female legislators is greater in magnitude than that of female ministers, but the difference is statistically significant at the 5% level.

We fit alternative model specifications to rule out alternative explanations by adding a time-varying control variable to the baseline model specification. Table A3 of the supporting online appendix reports the results. Footnote 8 First, we include a measure of women’s civil liberties from the V-Dem data that focuses on women’s freedom of domestic movement, freedom from forced labor, property rights, and access to justice. Women’s de facto rights would influence both women’s legal rights in economic opportunities and political representation. Second, we additionally control for the V-Dem’s women civil society participation index or the annual number of women’s international non-government organizations (INGO) in a country. Women’s movements may play an important role in creating the impetus for legislative reforms affecting legal gender equality (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018). Similarly, as more women’s INGOs exist in a country, the more that country is tied to transnational activism on women’s issues and faces greater pressure for legal gender equality (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Krook and Paxton2015). Third, leftist governments may be more likely to push for legal gender equality since they emphasize the expansion of social welfare benefits, which include some women-friendly policies (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2018). We thus include a dummy variable for leftist governments by using the measure of the largest governing party’s ideology. Fourth, we attempt to account for female labor market participation or the level of female education. As more women participate in the labor market or receive high levels of education, the more governments experience an increased demand for reforming legal discrimination against women and increasing women’s presence in influential decision-making bodies. Fifth, we add the measure of fertility rate obtained from the WDI as this factor may encourage reforms related to women’s economic rights (Fernández, Reference Fernández2014). Sixth, we include a natural log of official development assistance per capita. International aid donors emphasize gender equality, so foreign aid may be related to both legal gender equality and women’s descriptive representation. Last, we estimate a dynamic model by including a lagged dependent variable in the specification to control for the persistence of the WBL index. We find that the coefficient estimates for female legislators and ministers are similar to our benchmark estimates, and are stable and statistically significant across all the models.

Next, we estimate the effect of women’s descriptive representation on 8 indicators comprising the WBL index. Recall that the WBL index is an aggregate index consisting of 8 indicators: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets, and pensions. As Table 3 shows, the main finding based on the overall WBL index stands even when we examine 8 sub-indicators. The coefficient estimates of female legislators are positive and statistically significant in all models with the exception of the model for the pension indicator. Similarly, female cabinet members are positively and significantly associated with most indicators except the assets indicators.

Table 3. Using 8 indicators comprising the WBL index (FE estimates). Robust standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. All explanatory variables are lagged

*

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

, **

$p \lt 0.1$

, **

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

, ***

$p \lt 0.05$

, ***

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

.

$p \lt 0.01$

.

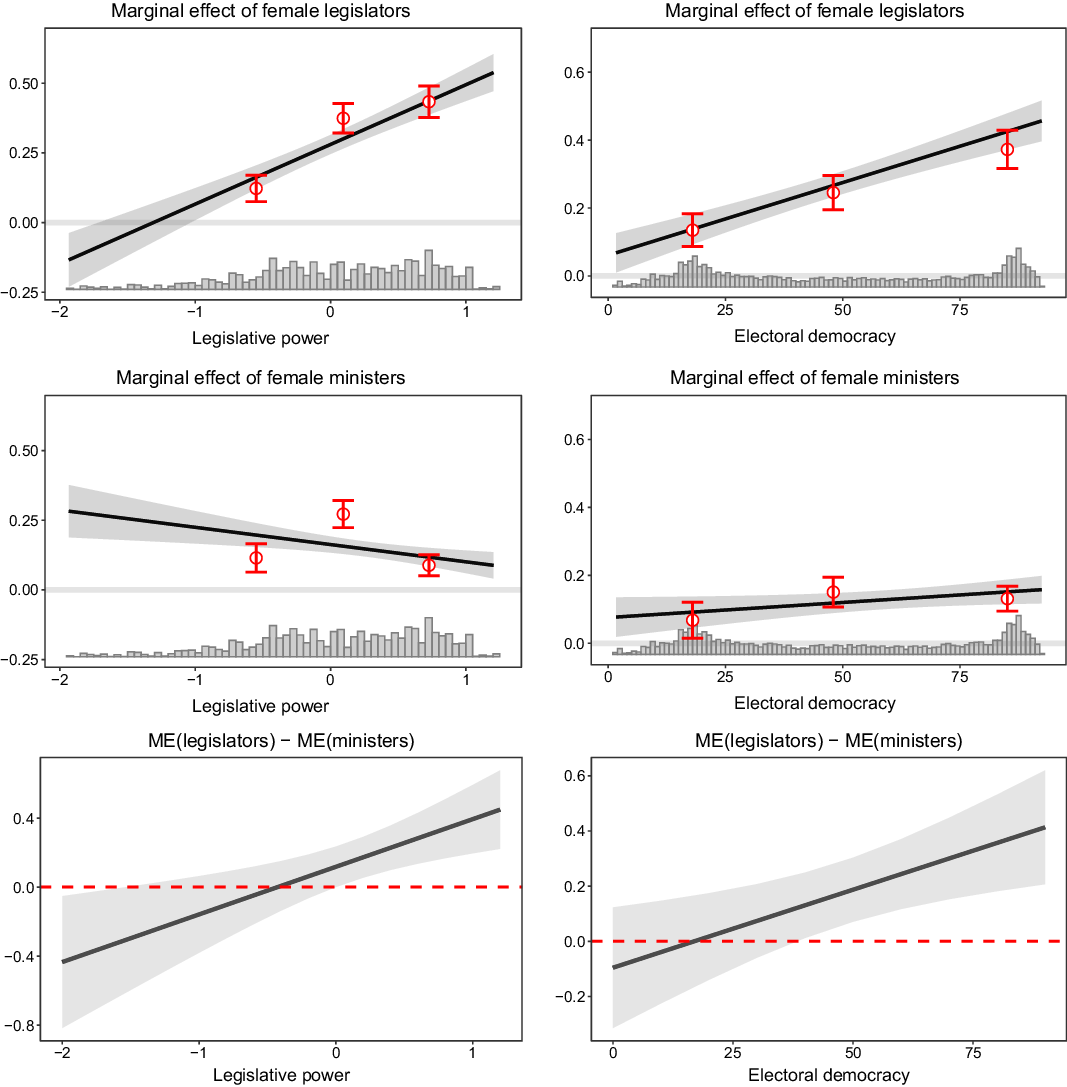

Table 4 provides a test of the conditional hypotheses. To test H2, we add two interaction terms to the model specification of Column 6 in Table 2: Female legislators × Legislative power and Female ministers × Legislative power. Column 1 shows that the estimate for Female legislators × Legislative power is positive and statistically significant, while the estimate for Female ministers × Legislative power is negative and statistically insignificant. The left panels of Figure 2, based on Column 1, provide supporting evidence for H2. They show that the marginal effect of female legislators increases but that of female ministers decreases in the level of the legislative power. Footnote 9 Particularly, the bottom-left panel indicates that when the legislative power is high (greater than zero), female legislators are more effective than female ministers, and the difference is statistically significant. On the other hand, the effect of female ministers is greater than that of female legislators when the legislative power is low. We find similar results when we split the sample into high and low legislative strength groups in Columns 3–4. We compute the country average level of the legislature’s law-making strength and split the sample into two groups using the median of the averages. Footnote 10 In the high legislative strength sub-sample, the marginal effect of female legislators is about five times greater than that of female ministers. Contrarily, the former is smaller than the latter in the low legislative strength sub-sample, although the difference is not statistically significant.

Table 4. Conditional effects of women’s descriptive representation (FE estimates). Robust standard errors clustered at the country level are in parentheses. All explanatory variables are lagged

*

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

, **

$p \lt 0.1$

, **

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

, ***

$p \lt 0.05$

, ***

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

.

$p \lt 0.01$

.

Figure 2. Conditional effects of women’s descriptive representation on the WBL index. Solid lines display the estimate of the marginal effect, while shaded areas display the 95% confidence intervals. The red symbols present the binning estimates.

Next, we test H3. Column 2 includes Female legislators × Democracy and Female ministers × Democracy. The estimate for Female legislators × Democracy is positive and statistically significant, and the estimate for Female ministers × Democracy is close to zero and statistically insignificant (see also the top-right and the middle-right panels of Figure 2). The right panels provide supporting evidence for H3 that the marginal effect of female legislators exceeds that of female ministers as the democracy level increases. The difference is also statistically significant when the democracy level is greater than 40. Again we find similar results when we split the sample into two equally-sized groups, high democracy and low democracy, using the previous method. The marginal effect of female legislators is greater than that of female ministers in both sub-samples, but the difference between the two effects is much greater and only statistically significant in the high democracy sub-sample.

Last, it is worth noting that the effects of female legislators and ministers on the WBL index remain positive across most values of legislative power (about 95%) and across all values of electoral democracy. This implies that even in non-democratic countries or in countries with weak legislatures, having more women in important policy-making positions contributes to improving legal gender equality. This might be because advancing women’s economic rights can produce tangible and intangible benefits without producing high political costs (Donno and Kreft, Reference Donno and Kreft2019). It may improve the regime’s reputation in the face of the international community but does not threaten the regime’s survival.

Robustness checks

To ensure the robustness of our results, we perform several additional analyses. Footnote 11 None of the following changes altered our central findings.

-

Exploring the relationship between legislative gender quotas and legal gender equality (Table A6 and Figure B5)

-

Employing alternative modeling for time trends: including a full set of year fixed effects, a cubic polynomial of time trend, or region-specific time trends (Table A7)

-

Estimating random-effects models (Table A8)

-

Using Driscoll-Kraay standard errors or robust standard errors adjusted for two-way clustering at the county and year level (Table A9)

-

Lagging right-side variables and varying the lags from 1 to 5 years (Table A10)

-

Dropping high-income OECD countries (Table A11)

-

Distinguishing between democracies and non-democracies by using a dichotomous measure of democracy (Table A11)

-

Excluding each particular region (Table A12)

-

Using individual sub-indicators of legislative power instead of the overall legislative power indicator (Table A13)

Discussion

We examine how women’s descriptive representation affects legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Our analysis reveals that as the share of women in important political decision-making bodies increases, legal reforms for legal gender equality of economic opportunity are more likely to occur. Both the percentage of female legislative members and that of female cabinet members contribute to legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Both variables have their own independent effects. The effects of both female legislators and ministers remain robust even when we control for socio-economic factors, such as economic development, oil income per capita, and female labor market participation, or political factors, including the level of democracy, women’s civil liberties, women’s civil society participation, a linkage to women’s INGO, and CEDAW ratification. This suggests that policies for gender equality are more likely to be formulated and implemented, as more women enter national legislatures or cabinet positions that have been dominated by men.

It is also worth noting that the relationship between women’s descriptive representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity holds under various contexts. We find similar results even when we remove developed countries that tend to have higher equality of economic opportunity across gender as well as higher levels of female descriptive representation. This implies that female policymakers can contribute to advancing women’s economic rights and eliminating legal discrimination against women even in developing countries or least-developed countries where legal gender discrimination tends to be more pervasive and persistent (Doepke et al., Reference Doepke, Tertilt and Voena2012). Our study shows that even though these countries have unpropitious socio-economic conditions for women’s legal economic rights, political empowerment of women might help to reduce the legal gender gap. We find similar results when we split the sample between democracies and non-democracies by using a dichotomous measure of democracy. Both the percentage of female legislators and that of female ministers are positively associated with the WBL index in non-democracies as well as democracies. This result provides a strong support for the argument for improving women’s political empowerment across the globe.

Last, our study shows that including more women in policy-making positions produce heterogenous effects across countries. Institutional or political context significantly shapes the influence of women in different positions of power on legal gender equality. Women’s legislative representation can better translate into legal gender equality when the legislature’s institutional policy power is greater and/or individual legislators have more personal professional power. Supportive of this argument, the legislature’s law-making power magnifies the effect of female legislators, making female legislators more effective than female ministers in improving legal gender equality when the legislature possesses greater law-making power. Contrarily, female ministers are better positioned than female legislators to initiate policy changes for gender equality and to promote female-friendly agendas when the legislature does not play an active role in the policy-making process.

Similarly, the level of democracy reinforces the effect of female legislators: the more democratic a country, the greater the effect of female legislators on legal gender equality. Given that it does not affect female cabinet ministers’ effectiveness, the relative influence of female legislators compared to female cabinet ministers is also greater in a more democratic country. On the other hand, when a country is fully authoritarian, there is little difference between female ministers and legislators. Consistent with these results, the supplementary analysis, reported in the online appendix (Table A5), indicates that the effect of gender quotas on legal gender equality increases either in the level of legislative power or in that of democracy. Taken together, the type of women’s descriptive representation effective in promoting legal gender equality of economic opportunities is conditional on a country’s institutional or political context.

Conclusion

This article examines the relationship between women’s descriptive representation and legal gender equality of economic opportunity. We focus on women’s presence in the legislatures and cabinets as an important determinant for legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Our analysis demonstrates that the percentages of both female legislators and female ministers are positively associated with legal gender equality of economic opportunity. It also shows that the effects of female legislators and ministers and their relative influence are conditional on the legislature’s law-making power and the level of democracy. This article provides additional evidence for the link between descriptive and substantive representation. It shows that women’s under-representation in important policy-making positions is an important background condition for the unequal treatment of women in economic opportunities.

Our findings do not necessarily imply that an increase in women’s descriptive representation leads to an improvement in women’s economic agency and empowerment since we focus on legal gender equality of economic opportunity. Studies show that de jure gender equality is positively correlated with women’s economic opportunity, and that gender egalitarian laws are necessary conditions for women’s economic agency and empowerment (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Jensenius and Nelson-Nuñez2019; Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, Djankov and Goldberg2020). Nevertheless, the focus on legal gender equality may produce a partial and flawed view of actual women’s economic opportunities. Even when little legal discrimination against women exists, social and cultural norms and practices may sustain discrimination in the society. Therefore, future study should examine how an increase in women’s descriptive representation affects women’s economic agency and empowerment.

Future work should also seek to answer how each type of women’s descriptive representation affects legal gender equality in different areas. We find that the effect of female legislators or ministers on each indicator of the overall aggregated WBL index varies across different indicators. As Htun and Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2018) argue, gender equality has many linked dimensions, and thus a policy promoting equality may pose a different challenge to existing values and institutions. This can produce different dynamics of reform and resistance across issues. Thus, it is necessary to explore the effect of women’s descriptive representation on different spheres of gender equality.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000352.