The use of i-longa is very different from that of apices in the tablets of the Sulpicii and the tablets from Herculaneum. For one thing, i-longas are far more common than apices. In the TPSulp. tablets I count 799 instances of i-longa (compared to 76 apices), which appear in all but 16 of the 127 documents.Footnote 1 In the TH2 tablets they appear in 26 documents out of 40, and I count 243 instances in total. They also differ in the range of phonemes which they represent. Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 104–8) discusses the use of <ì> in the tablets of the Sulpicii at some length, although without a rigorous collection of examples. He observes that it is found for long /iː/ (as might be expected on the basis of the grammatical tradition), for short /i/, and for /j/, both word-initially and word-medially between vowels.Footnote 2 The large numbers of i-longa in the tablets of the Sulpicii make a full investigation difficult, but 163 cases are used to write a synchronic short vowel (with 19 of these being vowels which were originally long), which equates to 20% of the total.Footnote 3

The Herculaneum tablets contain 243 instances of i-longa, of which there are 209 instances of <ì> representing a long vowel,Footnote 4 5 cases where it represents a long vowel subsequently shortened,Footnote 5 14 where it represents an original short vowel,Footnote 6 8 representing /j/,Footnote 7 and 7 representing original /i/ in hiatus, for which it is uncertain whether this represents /i/ or /j/ (on which see fn. 2 and p. 292 fn. 2).Footnote 8 Combining original /i/ and /i/ as the result of shortening (but not /i/ in hiatus) gives us a proportion of 19/243 (8%). Clearly <ì> is used to represent /i/ much less frequently at Herculaneum than in the tablets of the Suplicii.Footnote 9

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, Adams suggests that <ì> seems to be used particularly often on long /iː/ (or /i/ which was originally long) when it comes at the end of the word, and also particularly on the initial /i(ː)/ of a word, even where the i is short, in both cases as a decorative device. The problem with these claims is that in order to know if i-longa is used more often in a particular position we need to be able to compare the cases both where i-longa is used and where it isn’t used. So, to assess whether i-longa is used particularly when word-final we would need to count all instances of (long) final /i(ː)/ which was written with and without i-longa (which would be a very large task) and compare this with all instances of long /iː/ which are not word-final (which would be an immense task). I do not intend to attempt this process, but I would observe that the number of instances of final /iː/ is likely to be very high in the tablets, both because it appears in a large number of Latin endings and because genitives of the second declension feature particularly heavily in the lists of witnesses. Thus, the fact that a large number of instances of i-longa appear word-finally may reflect the very high number of instances of word-final long /iː/ rather than a higher ratio of i-longa usage in this environment.

Along similar lines, it struck me at first sight that in the more manageable Herculaneum corpus the use of i-longa seemed to be greater in the lists of witnesses on the tablets than in other contexts. However, this is probably a reflection of the frequency of the second declension genitive singular in -ī in that context, rather than being due to a difference in the usage of i-longa. I count 138 instances of i-longa used to write gen. sg. in -ī in witness lists, versus 136 instances of it being written without i-longa (i.e. practically 50% of instances). In other parts of the tablets, I have found 25 instances of the gen. sg. with i-longa, and 21 without it, a distribution which suggests that there is no difference between use of i-longa in witness lists and elsewhere.Footnote 10

To give an idea of the usage of <ì> in the tablets of the Sulpicii, I have collected all examples of <ì> and <i> at the beginning of a word. This is achievable thanks to the excellent analytical indexes in Reference CamodecaCamodeca (1999). This allows me to compare the distribution of word-initial <ì> when used to represent long /iː/, short /i/, and /j/. There are 39 instances of initial long /iː/ written with <ì>, and a further 8 written with <i> (83%). There are 174 examples of initial /i/, of which 65 are written with <ì> (37%). There are 153 examples of initial /j/, of which 96 are written with <ì> (63%). From this we can conclude that the use of i-longa word-initially is not solely ornamental, since if so, we would expect an equal distribution of use among the categories. These figures suggest that <ì> is being systematically used to represent /iː/, but not /i/. Use of <ì> for /j/ is much more common than for /i/, but also notably less common than for /iː/. If someone were to count all examples of /i/ followed by a consonant vs /i/ in hiatus in the TPSulp. corpus, the distribution could be compared with these figures to ascertain whether <ì> was being used intentionally to represent /j/ arising from /i/ in hiatus.

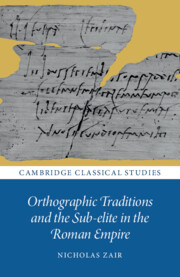

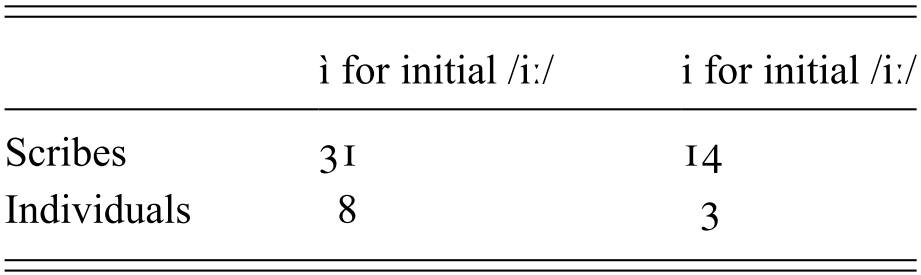

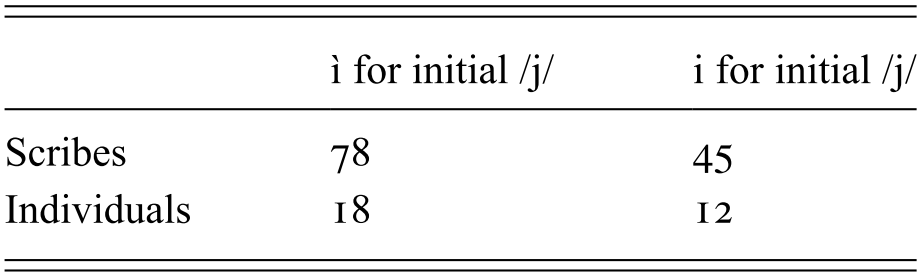

Since so many of the TPSulp. documents are chirographa, they allow us to test whether there is any significant difference in usage of i-longa between scribes and other individuals. The answer is yes: while there is no significant difference between scribes and other writers in use of <ì> to write /iː/ (Table 41) or /j/ (Table 42),Footnote 11 the scribes use <ì> to represent /i/ much more frequently than other writers (Table 43).Footnote 12

Table 41 Use of <ì> for /iː/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /iː/ | i for initial /iː/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 31 | 14 |

| Individuals | 8 | 3 |

Table 42 Use of <ì> for /j/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /j/ | i for initial /j/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 78 | 45 |

| Individuals | 18 | 12 |

Table 43 Use of <ì> for /i/ in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ì for initial /i/ | i for initial /i/ | |

|---|---|---|

| Scribes | 66 | 77 |

| Individuals | 11 | 32 |

This suggests a difference in the practice (and hence, presumably, the training) of scribes and individuals: scribes appear to be trained to use i-longa for short word-initial /i/, about half the time, whereas individuals only do so a third of the time. The words with initial short /i/ marked with an i-longa consist of id, ideo, in (and its misspelling im) and words beginning with in-, ipso, is, Isochrysi, ita, italum and item. There is no clear correlation between use of the i-longa on a short vowel and stress in TPSulp.; these correlate in 80 instances out of 163.

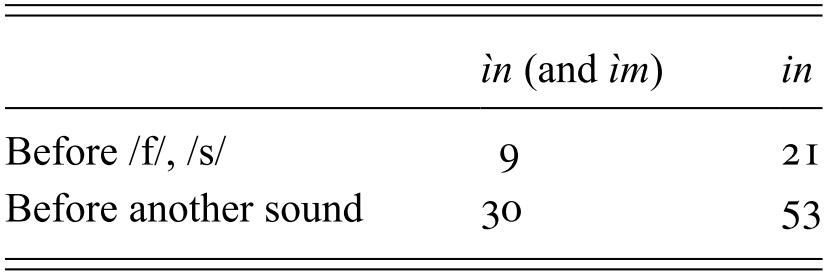

Given the very high amount of tokens of <ì> that consist of ìn and ìm (44 out of 77; all but 1 by scribes), I wondered whether there was some linguistic factor regarding in which could explain this distribution. Reference AllenAllen (1978: 65) notes that i-longa is found inscriptionally in sequences where in is followed by a word beginning with a fricative, where we would expect lengthening before nasal plus fricative clusters. But the tablets of the Sulpicii show no particular correlation between use of i-longa in in and a following fricative (Table 44).Footnote 13

Table 44 Use of ìn and in by following segment in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ìn (and ìm) | in | |

|---|---|---|

| Before /f/, /s/ | 9 | 21 |

| Before another sound | 30 | 53 |

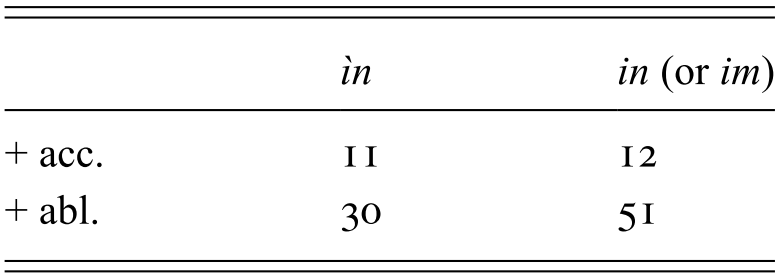

In the interests of completeness, I have also checked in the TPSulp. tablets whether there is any correlation between use and non-use of the i-longa in in and its differing semantics and case of its complement (Table 45).Footnote 14 Although ìn is found much more frequently followed by an accusative than by an ablative, no significant correlation is found.Footnote 15

Table 45 Use of ìn and in according to the case of its complement in the tablets of the Sulpicii

| ìn | in (or im) | |

|---|---|---|

| + acc. | 11 | 12 |

| + abl. | 30 | 51 |

Since I have found no linguistic factor which would explain the preponderance of i-longa used to write short <i>, it seems to me likely that scribes received training, or developed a practice amongst themselves, which encouraged them to use i-longa in this context, and especially in the word in. Adams may be right to see this practice as decorative, but in the light of the similar practices of the stonemasons of the Isola Sacra inscriptions (see Chapter 19) I suggest that the same reason applies: to increase legibility in a sequence of letters which involves several vertical strokes close together.Footnote 16

Other factors for use of <ì> on short /i/ might be similar to those found for apices, including a way of marking out names, and perhaps particularly imperial names. Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990: 106) observes in his corpus three examples of Tìb., stating ‘it is evidently a way to mark out the imperial praenomen carried by Tiberius and Claudius’ (c’est manifestement une façon de célébrer le prénom impérial porté par Tibère et Claude). In the tablets of the Sulpicii there are 28 examples of the abbreviation Tì for Tiberius, and only 5 of Ti., while in the Herculaneum tablets there are 8 of Tì. and 3 of Ti. A tendency for i-longa to be used in this abbreviation was also noted by Reference ChristiansenChristiansen (1889: 37–8).Footnote 17 However, I am not certain that this is due, as claimed by Flobert, to the celebrity of the emperors: it is the case that most, but not all, of the instances in the tablets of the Sulpicii refer to Tiberius or Claudius, who bore this name, while none of the instances at Herculaneum do. It is perhaps possible that the esteem attached to this name meant that the association of the abbreviation with i-longa spread to uses not referring to an emperor, and if so it must have lasted after Claudius’ death, since the tablets containing Tì. are mostly datable to the 60s AD. But it is also notable that the sequence TI is the kind in which lengthening of the <i> occurs for reasons of legibility in the Isola Sacra inscriptions.

One might even wonder if there could be more localised reasons for use of i-longa in some cases. In TPSulp. 45, the chirographum of one Diognetus, slave of C. Novius Cypaerus, we find (along with a number of other substandard spellings) ube for ubi ‘where’ and legumenum for leguminum ‘of pulses’ as a result of the falling together of /i/ and /eː/. In the scribal portion of the text these words are spelt ubì and legumìnum. Is it possible that the scribe reacted to Diognetus’ misspellings by emphasising the correct vowel with an i-longa?Footnote 18