INTRODUCTION

Stacey Abrams won the Democratic primary for governor in GA on May 22, 2018. Abrams secured a place in history books that night as becoming the first Black woman to ever win a major party's nomination for governor. As the former minority leader of the GA statehouse, small business owner, novelist, and Yale Law School graduate, Abrams was the most qualified candidate in the race. Yet, on an interview with The Breakfast Club, a syndicated hip-hop/urban radio show based in New York City, the day before the primary election, Abrams shared with the hosts that, “they don't think I'm viable, because I'm a Black woman with natural hair and no husband. That is a sentiment that is held by some. But what I will say, is that I am the most qualified candidate—Democrat or Republican running.”Footnote 1 Here, Abrams directly connects her response to critics who view her looks and marital status as impeding her ability to lead the state. Stacey Abrams's looks were also the center of an ad that ran in the Atlanta metro area that was put out by a political action committee. The focal point of the ad was on Abrams's natural hair and her decision to style herself with unprocessed hair. On social media, Stacey Abrams—who is ebony toned, heavy-set, and wears a natural twist out hairstyle—has been compared to Keisha Lance Bottoms, the current mayor of Atlanta,—who is slender, with straight hair that is coiffed in a close-cropped style, and is honey brown in skin tone. In Abrams's historic candidacy, and as the political careers of these two women progress, their appearances as Black women will be salient to voters and political commentators.

What is the effect of variation in skin tone and hairstyle on evaluations of Black women candidates? The first thing people notice when they see political candidates is the candidate's phenotype. Scholars working on candidate evaluation have noted that simply looking better is a bonus for candidates (e.g., Ahler et al. Reference Ahler, Citrin, Dougal and Lenz2017; Banducci et al. Reference Banducci, Karp, Thrasher and Rallings2008) while those working on race and candidate evaluation note that skin color is consequential for Black candidates (Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). At the same time, decades of research have tested whether gender stereotypes undermine the candidacies of women (e.g., Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Dolan and Kropf Reference Dolan and Kropf2004; Kahn Reference Kahn1994; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002). No study in the literature to date, however, speaks to how Black voters evaluate Black women candidates who vary in phenotype. We contend that phenotype is an important aspect of voter perceptions of Black women candidates. We develop and test two hypotheses in the context of voting and trait evaluations: the empowerment hypothesis and the internal discrimination hypothesis. We conducted a survey experiment that varied a Black woman politician's skin tone (lighter or darker) and hairstyle (straightened, naturally curly, or braided). We found that the interaction of dark skin and natural hair had a negative effect on respondents’ trait impressions of the candidate, but a positive effect on Black women's reported likelihood of voting for the candidate. By using Black women candidates as a case, our findings add nuance to the existing work on skin tone and Black women's political behavior (e.g., Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Philpot and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). Our findings challenge the notion that more Afrocentric candidates face barriers to office: not necessarily for Black women among Black women.

Since the election of Trump in 2016, there has been a renewed interest in intersectional approaches to voter behavior, particularly as scholars seek to explain why White women voted for Trump (Junn Reference Junn2017). We center the inquiry into contemporary voter behavior on Black women. Black women are the most reliable Democratic voters, voting for Clinton in 2016 at more than 90 percent. November 2017's local and state elections also witnessed large levels of support from Black women who helped make decisive victories for the NJ and VA governor's race. Notably, Black women were credited for Roy Moore's Senate loss in AL (Packnett Reference Packnett2017). As candidates, Black women also won key races: Yvonne Spicer, mayor of Framingham, MA; Vi Lyles, mayor of Charlotte, NC; Mary Parham-Copelan, mayor of Milledgeville, GA; Andrea Jenkins (a transgender Black woman), Minneapolis City Council; Ashley Bennett, county board in Atlantic City, NJ; and London Breed, mayor-elect of San Francisco, CA. The significance of these victories indicates that Black women are a powerful voting bloc as well as viable candidates for political office. Our research speaks directly to contemporary developments in the Trump era: how a demographic that is vital for the Democratic party will evaluate new candidates for office—Black women.

RELEVANT LITERATURE

We situate our study at the intersection of two literatures: candidate evaluations and the politics of hair and skin tone.

Evaluations of Women Candidates and Black Candidates

Scholarship has consistently indicated clear differences in evaluations of women candidates and Black candidates. Through experiments and surveys, scholars have shown that voters think that women politicians are more compassionate, more likely to prioritize family and women's issues, warmer, more equipped to deal with education issues, more liberal and Democratic, and more feminist than men (e.g., Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Burrell Reference Burrell1994; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993a, Reference Huddy and Terkildsenb; Kahn Reference Kahn1996; Koch Reference Koch2000). Conversely, male politicians are more intelligent, more conservative, stronger, and are better suited to dealing with issues of crime, defense, and foreign policy (Lawless Reference Lawless2004). Deloitte and Touche (2000) found that the mass public had more confidence with a male commander in chief, particularly around issues of foreign policy. Issue competency stereotypes may have more to do with the political socialization that implicitly teaches Americans that men are better at handling issues like crime and foreign affairs or are more emotionally suited to politics (Huddy Reference Huddy2001; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2003). These stereotypes about a candidate's personal traits shape voters’ likelihood to vote for either a male or female candidate (Kahn Reference Kahn1996; Lawless Reference Lawless2004; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002). Indeed, women are more likely to support women candidates (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1995; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002). Support for women candidates is more frequent among the higher educated (Dolan Reference Dolan1996), younger citizens (McDermott Reference McDermott1998), and infrequent church goers (Welch and Sigelman Reference Welch and Sigelman1982). Furthermore, ethno-racial minorities prefer women in government more so than their White counterparts (Dolan Reference Dolan1996). However, other studies have found that gender has less of an effect on voter choice in real-world elections. Instead, it is a candidate's party identification and incumbency that make the biggest difference (Dolan Reference Dolan2014a; Dolan and Kropf Reference Dolan and Kropf2004; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2003). Additionally, gender stereotypes may only be relevant to the politically uninformed (Bauer Reference Bauer2015). Still, gendered stereotypes about political leadership remain pervasive. Though informative, these studies have not examined whether these issues apply to Black women.

Akin to the research on gender, Black politics scholars have found that voters apply biases to Black candidates. Although some have shown that Whites reportedly will vote for a qualified Black candidate (e.g., Schuman et al. Reference Schuman, Steeh, Bobo and Krysan1997), others have found that racial prejudice may not motivate Whites’ vote choice (e.g., Citrin, Green and Sears Reference Citrin, Green and Sears1990). Indeed, Black politicians may comprise an exceptional “subtype” of Black people in the minds of voters (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2011). Still, racial prejudice may influence evaluations of a Black candidate's personality and issue positions (Moskowitz and Stroh Reference Moskowitz and Stroh1994). Variation in skin tone of Black candidates may be the deciding factor in Whites’ likelihood to vote for a Black candidate (Ashmore and Del Boca Reference Ashmore, Del Boca and Hamilton1981; Fiske and Taylor Reference Fiske and Taylor1991). The implicit bias toward lighter-skinned Blacks over darker-hued Blacks may have been witnessed in Whites’ preferences for Brady over Jackson (Citrin, Green, and Sears Reference Citrin, Green and Sears1990). Like the women and politics literature, this body of work is informative, but tends to neglect the study of Black women candidates.

Research using an intersectional lens illuminates the politics of Black women (Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach Reference Purdie-Vaughns and Eibach2008). The literature suggests that Black women are not necessarily doubly disadvantaged because of their race and gender in American electoral politics. For Black voters, descriptive representation matters (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Tate Reference Tate2001). Black women have developed a distinct Black female consciousness, which influences their political behavior and ideologies (Simien Reference Simien2006). As such, Black women differ from Black men and White women in their evaluation of Black leaders and political events (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998). Black women are the strongest supporters of Black women candidates (Philpot and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007), and Black women candidates can successfully mobilize Black voters, regardless of gender (Philpot and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007). Black women's support of Black women candidates may be due to prioritizing racial interests and identities over gendered interests and identities (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998; Mansbridge and Tate Reference Mansbridge and Tate1992). However, other scholarship has indicated that Black women cannot separate or rank their racial and gendered identities, and they instead form a new identity that represents the interlocking of their parts (Brown and Banks Reference Brown and Banks2013; Orey et al. Reference Orey, Smooth, Adams and Harris-Clark2006; Simien Reference Simien2006). Other work shows that Black women candidates may be harmed by perceptions of Black women as “assertive” (Hicks Reference Hicks2017, 21). In short, intersectional approaches suggest that Black voter responses to Black women candidates may be different from voter responses to White women candidates and Black men candidates.

The Politics of Hair and Skin Tone

Colorism and hair texture preferences have consequences that impact Black women's lives in meaningful ways. Importantly, skin tone, hair texture, and the combination of skin and hair have distinct meanings. For women, hairstyle is a malleable marker that communicates race (Sims, Pirtle, and Johnson-Arnold, Reference Sims, Pirtle and Johnson-Arnoldn.d.). To start discussions of Black women's bodily esthetics, namely their hair practices, with enslavement, often reduces scholarly understandings of Black women's bodies as devoid of self-care and humanity. However, it may be necessary to belabor these hair practices to demonstrate the importance of contextualizing why hair and skin tone remain such important factors in the lives of Black women. Intra- and inter-racial ideas about Black women's beauty practices have existed since the onset of enslaved African women on this continent. Black esthetics, under the inhumane conditions of slavery, were part of grooming practices for health and convenience for enslaved Black women (Blackwelder Reference Blackwelder2003). Many bondswomen braided or used head wraps to protect their coils from sun damage. They used products like kerosene, butter goose grease, lye, and coffee, to clean, dye, or straighten their hair. Many of these products and methods left enslaved Black women with permanent hair loss. White slave owners would also punish bondswomen by shaving their heads as way to eradicate a sense of self, beauty, and culture (White and White Reference White and White1995).

Stemming from the periods directly following enslavement and later into the New Negro movement, Blacks used the politics of adornment to signal their status to demonstrate their place in the newly changed American society (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2017). Beauty culture and the politics of appearance for Black women were used as powerful tools to combat the prevailing (and often contradictory) stereotypes of Black women in the Jim Crow era. Through the archetypes of the Mammy, Jezebel, and Sapphire, prevailing stereotypes of Black women as lascivious, savage, lazy, vulgar, matronly, and unconcerned with their appearance abounded (Harley Reference Harley1982). After emancipation, Black women created new models of Black esthetics by altering, adorning and maintaining their physical appearance (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2007). Black women's bodies became physical sites to challenge ideas about race, gender, sexuality, class, and labor. Bodily esthetics, particularly Black women's beauty culture, were used to shed vestiges of enslavement and a way to assert personal autonomy (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2017).

Black women's expanded options for self-expression and transformative bodily esthetics within this period dovetailed with greater demands for challenging White cultural hegemony and Black sexism. African American women's hair was the frequent topic of conversation in racial uplift circles (e.g., Marcus Garvey), advertisements, and editorial pages within Black-owned papers (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2017). Take, for example, this 1910 quote from the Washington Bee in which Black businessmen and journalist Calvin Chase wrote:

We say straighten your hair ladies, beautify yourselves, make those aggravating, reclusive, elusive, shrinking kinks long flowing tresses…even if it takes every ounce of hair straightening preparation that can be manufactured…even God, who discriminated against our women on this hair proposition, knows that straight hair beautifies a woman (Calvin Chase, Washington Bee, March 15, 1910)

While positions like Chase's were paramount, there were others—particularly Black women themselves—who contributed to an alternative discourse around Black women's beauty and bodily esthetics (Gill Reference Gill2010).

In future generations, Blacks would later more publicly embrace a beauty culture that was less beholden to White corporeal tastes. Lester (Reference Lester2000) claims that it was not until the 20th century that Blacks were more fully able to resist the image of White beauty and chose primarily Afrocentric bodily esthetics. The Black Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s reified that hair was both important and political. The Afro would challenge hegemonic beauty norms that devalue natural Black features. Indeed, Blackness became an attribute and “Black is Beautiful” became popular saying that acknowledged self-determination while also uplifting the self-esteem of Black women (Mercer Reference Mercer and Gelder2005). We are currently living in a resurgence of “Black is Beautiful” moment in which more and more women have decided to stop chemically processing their hair to “go natural.” Black women, many of whom may not have seen their hair in its unprocessed state, are finding ways to embrace their hair, while at the same time learning how to love and accept themselves (Bey Reference Bey2012). Indeed, Zina (Reference Saro-Wiwa2012) notes that racial consciousness is a necessary first step that a Black woman must take before going natural. Because Black hair and Black bodies have remained a site of political contestation throughout American history and within the American imagination, demonstrating that wearing natural hair today is a radical expression of self-acceptance, an evolution of Black political expression.

Given this history, it is necessary to view Black beauty culture holistically to understand the sustained salience of hair in Black communities. Hair is not just hair for Black women. For African Americans, hair texture is laden with value distinctions, such that hair can alter the significance attached to skin tone—making a lighter-skinned Black woman “Blacker” or a darker-skinned Black woman more “assimilated” into Whiteness. Scholars have found that of generations of racial mixing have produced variations of Black hair textures—from coiled, kinky, wavy, curly, and straight (Sellers Reference Spellers, Jackson and Richardson2003; Spellers Reference Spellers, Martin, Nakayama and Flores2002). Kinkier hair requires a considerable amount of oil to prevent breakage and grows slower than straighter hair which requires less oil and grows longer. Because most Black women have kinkier hair, they do not have the texture or the length to confirm to American beauty standards (Robinson Reference Robinson2011). Conversely, kinkier hair allows more diversity in hairstyles because it is the most versatile. It can be “twisted, locked, braided, weaved, curled, dyed, fried and laid to the side” (Spellers Reference Spellers, Martin, Nakayama and Flores2002, 235). Although kinkier hair may be more flexible with respect to styling options, its linkages to African heritage makes it undesirable. Black hair hierarchies determine “good” and “bad” hair valuations. Good hair is the absence of kink while bad hair is prominent kink. Good hair is considered far more attractive, it is soft to the touch, manageable, ability to grow long, and requires minimal intervention to be considered beautiful (Craig Reference Craig2006; Robinson Reference Robinson2011). Black women's appearance via hair texture and skin tone is on a beauty continuum that ranges from “privilege and opportunity to discrimination and social isolation” (Robinson-Moore Reference Robinson-Moore2008, 81). Hair texture variation impacts Black women's racial experiences and mediates the severity of discrimination that she may face (Treviño, Harris and Wallace Reference Treviño, Harris and Wallace2008).

Researchers have found that Black women's hair impacts how Black women are treated and perceived. Studies have shown that Americans prefer Black women with smooth hair rather than natural hair (Rudman and McLean Reference Rudman and McLean2016; Woolford et al. Reference Woolford, Woolford-Hunt, Sami, Blake and Williams2016). Hair not only serves a marker for racial identification, but also beauty (Robinson Reference Robinson2011). Indeed, tightly coiled hair texture is uniquely tied to Blackness. This type of hair texture has been a marker of racial identity (Banks Reference Banks2000) and is linked to beauty norms (Craig Reference Craig2006). The main issue, however, is that choice in identity acquisition is not as readily available among members of low status groups (see McKenna and Bargh Reference McKenna and Bargh1998). These less permeable groups are theorized as having an internalized group identity.

Because American beauty standards are tied to race, Black women experience a disadvantage that is unique to their race and gender identity. For example, using experiments and images of Black women with various hairstyles and White women with straight hair, Opie and Phillips (Reference Opie and Phillips2015) found that straight hair was associated with higher perceptions of professionalism (Study 1), and that even Black respondents viewed Black women with un-straightened hair as having “inappropriate” and/or “problematic” looks for “corporate America” (Study 2). Furthermore, there are noticeable intra-group gendered differences in views of how Black women should wear their hair. Rudman and McLean (Reference Rudman and McLean2016) found that Black men preferred Black women celebrities such as Janet Jackson, Viola Davis, and Solange Knowles to have smooth hair. However, Black women did not express a preference and liked the celebrities with both natural and straight styles. Researchers found similar results in a national survey that assessed views of Black women's natural hair. McGill Johnson et al. (Reference McGill Johnson, Godsil, MacFarlane, Tropp and Goff Atiba2017) found that Black women with natural hair were most supportive of women with textured hair than any other demographic group. The findings also indicated that Millennial “naturalistas” have more positive attitudes toward textured hair than all other women. However, McGill Johnson and colleagues found that while Black women celebrate natural hair, they also perceive a high level of social stigma against textured hair. This study confirmed a “hair paradox” in which Black women have positive explicit attitudes toward natural hair, but because of social pressures, have an implicit bias against textured hair (McGill Johnson et al. Reference McGill Johnson, Godsil, MacFarlane, Tropp and Goff Atiba2017, 13). Black women's perception of beauty and desire to conform to White standards of beauty has serious impacts on this population. Indeed, many women in McGill Johnson and colleagues’ survey noted they have significant anxiety around related to their hair and hair maintenance. Thus, on the one hand, Black voters may take pride in seeing a candidate with dark skin and natural hairstyles, but on the other hand, they may favor one with straightened hairstyles.

The significance of hair texture and skin tone is not easily separated. Colorism, an intra-ethnic hierarchy that values lighter skinned ethnics (Herring Reference Herring, Herring, Keith and Horton2004), communicates that people of color with phenotypical features that are closer to Europeans are more desirable (Hunter Reference Hunter2005). Scholars have found that life expectancy and mate selection (Hughes and Hertel Reference Hughes and Hertel1990; Hunter Reference Hunter1998), socioeconomic opportunities (Hill Reference Hill2000); prison sentencing (Hochschild and Weaver Reference Hochschild and Weaver2007), trait impressions (Maddox and Gray Reference Maddox and Gray2002), and electoral outcomes (Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012) are all linked to colorism. Skin color, like hair texture, has remained a powerful indicator of societal attitudes and treatment of Blacks (Neal and Wilson Reference Neal and Wilson1989; Okazawa-Rey, Robison, and Ward Reference Okazawa-Rey, Robinson and Victoria Ward1987). After the abolition of slavery, skin color remained a form of status acquisition (Okazawa-Rey et al. Reference Okazawa-Rey, Robinson and Victoria Ward1987). Preferential treatment that was awarded to Blacks, both in intra- and interracial contexts, conveyed that Blacks who physically conformed to White standards of beauty would have better and more rewarding lives (Gatewood Reference Gatewood1988). During the Black Power and Civil Rights Movements, “Black is Beautiful” would challenge these hegemonic norms around colorism (Neal and Wilson Reference Neal and Wilson1989). To be clear, lighter skin became less uniformly desirable whereas dark skin remained undesirable, brown skin tone was highly desired (Goering Reference Goering1971). For Black women, however, light skin still received a premium over dark skin. Lighter-skinned Black women were more likely to marry Black men of higher status than their darker-skinned counterparts (Goering Reference Goering1971). The salience of racial physiognomy remains paramount in our society. Take, for example, the mixed messages that Blacks receive in today's society. They are taught to be proud of their skin color, but remain “color struck” in noticeable ways by attending and responding to different shades of Black skin (Neal and Wilson Reference Neal and Wilson1989). Given the nation's long history of racism and colorism, it is unsurprising that skin color is a multidimensional construct that consists of cognitive, affective and behavioral components (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Cash and Lewis1989).

Hair texture and skin tone combine to influence body-image perceptions, attitudes and ideals among Blacks. This means that for many Blacks, evaluations of bodily esthetics are jointly assessed in terms of hair texture and skin tone. Because body-image is more salient of a concern for women (Cash and Brown Reference Brown, Cash and Lewis1989; Gutherie Reference Gutherie1976), and because hair texture has a storied history and present (Gill Reference Gill2010; Lindsey Reference Lindsey2017), we center our study on Black women. Furthermore, research by Brown (Reference Brown2014) demonstrates that for Black women state legislators, hair texture and skin tone—in tandem—contribute to the life experiences of these lawmakers. Legislators, like non-elected Black women, face similar opportunities and challenges that are uniquely related to both hair texture and skin tone. The common practice of using only skin tone and rarely hair texture to evaluate Black political elites fails to capture the dynamism of these bodily attributes influence perceptions of these candidates. It is the interaction of skin tone and hair texture, along with the historical legacies that have shaped the current cultural and political contexts, that dictates voter preferences for some Black women candidates.

We draw on the historical significance of hair and skin tone for the lives of Black women to study voter responses to Black women candidates who vary in phenotype. Feminist scholarship has presented two dominant views of Black women candidates: in one, Githens and Prestage (Reference Githens and Prestage1977) argue that Black women must overcome race and gender—a double disadvantage; whereas in the other, Darcy, Hadley, and Kirksey (Reference Darcy, Hadley and Kirksey1993) claim that Black women have fared better than their White counterparts in similar electoral environments. Extant literature indicates that Black women lawmakers are keenly aware of (a) how their bodies and somatic experiences are racialized and gendered, (b) the ways in which their bodies fall outside the hegemonic constructions of beauty and femininity, and (c) the impact of race/gender-based stereotypes on how colleagues and voters perceive them (Brown Reference Brown2014). For Black women, hair and skin tone are deeply political. Yet, scholars have little understanding of how Black women's skin tone and hair texture affect their chances of winning elected office. Because of the raced-gendered constructions of beauty, Black women office-seekers may face different challenges and opportunities in their self-presentation than Black men, White men, and White women. We contend that Black women's features may also impact voters’ perceptions of them.

THEORY AND HYPOTHESES

We draw on research in social psychology to identify two hypotheses, which we call the empowerment hypothesis and the internalized discrimination hypothesis. We derive the empowerment hypothesis from social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). Social identity theory is useful for understanding the underlying processes of evaluations of Black women candidates who vary in skin tone and hairstyles. From this perspective, social identity is understood as part of an individual's self-concept originating from her knowledge of her membership in a social group (or groups). This connection is tied together with the value and emotional significance that is attached to group membership (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981). When social identity becomes salient and people define themselves in terms of the same shared identity, they tend to see themselves as more alike due to the defining attributes of their identity rather than due to their personal characteristics. This common identity produces socially validated knowledge and shared beliefs about ways of perceiving, thinking, and behavior. The collective self then reflects the collective realities of the group. Thus, social identity theory is a useful and practical theoretical tool for examining an individual's behavior in a range of contexts (e.g., Ashforth and Mael Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; van Leeuwen, van Knippenberg, and Ellemers Reference van Leeuwen, van Knippenberg and Ellemers2003).Footnote 2

Social identity theory suggests the empowerment hypothesis. It is plausible that exposure to a Black woman candidate with darker skin and naturally curly or braided hair communicates her solidarity and identity with the group, and in turn, her appearance helps cultivate support from that group. Her candidacy may grant legitimacy to the state, and ultimately have an empowering effect on Black voters (e.g., Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999, 648–50). We build on the social identity theory hypothesis that groups seek to redefine “comparisons which were previously negative” to be “perceived as positive” (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986, 20).Footnote 3 According to Banks (Reference Banks2000), Black hairstyles can never escape political readings. Black hairstyles are a cultural esthetic that seeks to valorize Blackness. For example, consider Marcus Garvey's instructive statement, “Don't remove the kinks from your hair! Remove them from your brain” (Byrd and Tharps Reference Byrd and Tharps2001, 38). Both the Afro and dreadlocks styles redefined Blackness as a desirable attribute. The symbolic and political meanings of some natural hairstyles signal a shift from the stigma of curly, kinky hair into emblematical hairstyles of pride and pro-Blackness. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Afro symbolized Black Pride as Black Panthers and Angela Davis wore this style. Dreadlocks also symbolized racial pride, Black consciousness, and perhaps religious (Rastafari) connections. Today, it is common to see both styles worn by both men and women. Often, these styles are often a fashion statement by its wearers more than a political statement. Yet, as Mercer (Reference Mercer1994) so aptly points out, these styles have origins in radical political traditions.

Within the past decade, a natural hair movement has arisen that rejects the dominant beauty standard and pushes back against Eurocentric norms of Black women's beauty. In choosing to redefine the norms of Black women's beauty, “naturalistas” have begun to wear their natural hair and challenge conventional norms of what is acceptable, attractive, appropriate, and professional. Indeed, there has been a 34% decline in the market value of relaxers (McGill Johnson et al. Reference McGill Johnson, Godsil, MacFarlane, Tropp and Goff Atiba2017). Because of its connection to expressions of Black pride, many people view un-straightened or natural hairstyles as an outward manifestation of pro-Black political ideology.

Given the political connotation of natural hairstyles for Black women, particularly natural hairstyles, there may be an empowering effect of seeing a candidate with darker skin and natural hair, such that Black voters respond favorably to a candidate with Afrocentric features. Her appearance may communicate “I am one of you” (Fenno, 58). Indeed, work on Black male candidates contends that skin tone is used as a “sharpening cue” for Black Democratic conservatives (Lerman, McCabe and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015). That work found that voters viewed light-skinned Black candidates as indistinguishable from White candidates, suggesting that Black respondents may react positively to a darker-skinned Black woman candidate. The empowerment hypothesis suggests that the positive effect of a darker-skinned candidate should be amplified by natural hair, as the two together visually represent Black pride and empowerment. Thus, by manipulating phenotype, we seek to manipulate perceptions of the candidate's connection to Blackness. This leads us to test the empowerment hypothesis:

Empowerment hypothesis: The interaction of dark skin and non-straight hair will have a positive effect on Black respondents' likelihood to vote for a Black woman and rate her more favorably. If we find that together, darker skin and non-straight hair increase the likelihood of voting for and describing the candidate with favorable traits, then this hypothesis will be supported.

We derive the internal discrimination hypothesis from assimilation theory, and the issues that stem from the pressure on minorities to assimilate. Our alternative hypothesis is that Black respondents will penalize a Black woman who appears more Afrocentric as a function of her perceived inability to assimilate into the “mainstream,” White, culture. Traditional, straight-line assimilation theory posits that over time, immigrants eventually assimilate into the majority, adopting its customs and shedding their ethnic attachments (Alba and Nee Reference Alba and Nee1997). While this may be true for White immigrants, assimilation may be challenging for immigrants who are clearly demarcated as outsiders due to darker skin and non-White phenotypes (Portes and Zhou Reference Portes and Zhou1993, 76). One underlying current of the notion of assimilation is that non-Whites, immigrants, and non-immigrants alike, are expected to adopt Whiteness, relinquishing all attachments to non-Anglo culture (Gordon Reference Gordon1961). The social and economic benefits of assimilating into Whiteness create opportunities for intragroup conflict. Intragroup discrimination may occur against those who perceived as less “assimilated” into American Whiteness. For example, discrimination from other Latinos is salient to Afro Latinos (Lavariega Monforti and Sanchez Reference Lavariega Monforti and Sanchez2010), Asian Americans may invoke the term “FOB (fresh off the boat)” to describe new immigrant co-ethnics (Pyke and Dang Reference Pyke and Dang2003), and color-based discrimination is salient to darker-skinned Black women in interactions with Black and White people (Uzogara and Jackson Reference Uzogara and Jackson2016). In response to the pressure to conform to Whiteness, some communities of color, and in the context of this study, Black Americans, may adopt the politics of respectability, or the belief that if one adjusts one's individual behavior, one can avoid the constraints of systemic racism and prejudice (Harris Reference Harris2014; Jefferson Reference Jefferson2018).

Turning to the political implications of appearances for Black women, we hypothesize that Black respondents will reject a candidate who appears more Afrocentric. While Black women who choose to wear their hair naturally may do so to reject imposed Eurocentric beauty standards, Black women who opt to straighten their hair are also making political statements. Black-owned companies, such as those founded by Black women such as Madame C. J. Walker, Sara Washington, and Annie Turbo Malone, promote straight or wavy hair as a method of treating damaged hair, scalp disease, and promoting hair growth (Walker Reference Walker2007). African American beauty culturists straightened their hair to illustrate how to care for Black hair in a progressive and modern way. These culturists countered the negative images of Black womanhood by presenting positive and healthy images, and promoted a strong racial identity through empowering women to feel beautiful in their skin. While Black beauty culture as a consumer enterprise demarcates class dynamics within the Black community, it also epitomizes Black economic independence—particularly until White business began to incorporate Black hair care products, such as L'Oreal's purchase of Soft Sheen (Walker Reference Walker2007). Straightened tresses, for some Black women, enable social mobility. Rejecting ethnic communalism in favor of assimilation is a survival strategy for some who try to gain acceptance in White mainstream society (Hooks Reference Hooks1995). Thus, a Black woman who chooses to straighten her hair may ultimately select into assimilating into Eurocentric beauty standards to advance socioeconomically, and for some, engage in respectability politics. A Black woman politician who presents herself as more Afrocentric may encounter co-racial resistance, as Black voters may view her as less willing to assimilate into White standards of beauty and behavior to rise socioeconomically. As such, we test following:

Internal discrimination hypothesis: The interaction of dark skin and non-straight hair will have a negative effect on Black respondents’ likelihood to vote for a Black woman and rate her less favorably. If we find that together, darker skin and non-straight hair decrease the likelihood of voting for and describing the candidate with favorable traits, then this hypothesis will be supported.

DATA AND METHOD

We conducted an online survey experiment on 1,292 respondentsFootnote 4 who identified with a non-White category on May 17, 2017 on Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk), who were paid $1.00 for their participation. In this article, we focus our findings on the 516 Black respondents, and Table 1 reports the descriptive characteristics of this sample.Footnote 5

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

The merit of using mTurk for experimental research is an ongoing debate (e.g., Berinsky, Huber and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Clifford, Jewell and Wagonner Reference Clifford, Jewell and Wagonner2015; Huff and Tingley Reference Huff and Tingley2015; Logan et al. Reference Logan, Chandler, Seth Levine and Strolovitch2017; Thomas and Clifford Reference Thomas and Clifford2017). We recognize the strengths and weaknesses of using mTurk for research. On the one hand, the sample we collected from mTurk is relatively young: the average age of Black women in our sample is about 35 (34.6), while the average age for Black men is about 31 (30.7), and it is possible that mTurk is unlikely to include older generations of Black respondents. Given generational differences in the decision to straighten one's hair or wear it naturally, one of the drawbacks to using mTurk is that we may simply be less likely to pick up Black women who would punish a candidate like Brenda Johnson for wearing her hair naturally. On the other hand, considering the current wave of candidates for office and the large young population of potential voters of color more generally, the younger respondents on mTurk offer a glimpse into the future of American politics. Future studies should aim for more nationally representative samples.

We used Adobe Photoshop Creative Cloud to create six conditions in which we altered the hairstyle (braids, straight hair, or naturally curly hair) and skin tone (lighter or darker) of a Black woman. We used templates from Black women politicians’ websites to create a fictional webpage and named our candidate Brenda Johnson.Footnote 6 We programed our survey using Qualtrics. After providing informed consent and answering demographic questions, respondents answered questions about identity, other questions used in larger surveys, such as the American National Election Study and the 2008 National Asian American Survey (Ramakrishnan et al. Reference Ramakrishnan, Junn, Lee and Wong2012), and in previous candidate evaluation and political behavior research (Adida, Davenport and McClendon Reference Adida, Davenport and McClendon2016; Lerman, McCabe and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Newman et al. Reference Newman, Merolla, Shah, Casarez Lemi and Ramakrishnann.d.), including questions that measure candidate gender stereotypes (Dolan Reference Dolan2014b) used in other research on women candidates (Merolla, Sellers, and Lemi Reference Merolla, Sellers and Casarez Lemi2017), and questions that reflect past theories of evaluations of Black women candidates (Philpot and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007, 60) that use the notion of “linked fate” (Dawson Reference Dawson1994). Participants were randomly assigned to one of six experimental conditions using the Qualtrics randomizer.Footnote 7

After exposure, respondents answered questions commonly asked in research on candidate evaluation (Alexander and Andersen Reference Alexander and Andersen1993; Lerman, McCabe and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; McConnaughy et al. Reference McConnaughy, White, Leal and Casellas2010; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). We also included dependent measures that asked respondents which groups within the legislature the official is likely to work with, and with which organizations she is likely to work and donate, as past work on minority elites suggests phenotype may condition legislators’ perceptions of political relationships (e.g., Brown Reference Brown2014; Lemi Reference Lemi2018). We use some of these measures as manipulation checks, which may be found in the Appendix. The order in which our dependent variables were asked was randomized. As our hypotheses focus on empowerment or internal discrimination, we report our findings for the likelihood of voting and trait evaluations, as the two sets of variables allow us to determine whether phenotype encourages or discourages support for a co-racial candidate and assignment to various traits to the candidate.

FINDINGS

Our two dependent variables are the reported likelihood of voting for Johnson and perceptions of traits that describe Johnson. We processed our data using linear regression with robust standard errors (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2012), and we interacted skin tone with hairstyle. To explore heterogeneous effects among men and women, we ran separate models. All results for each model are reported in the Appendix. The results depict a puzzle: Black women are more likely to vote for a darker-skinned Black candidate with natural hair, but Black men and women view Johnson less favorably on trait evaluations when her skin is dark and her is natural.

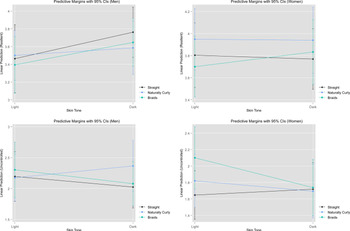

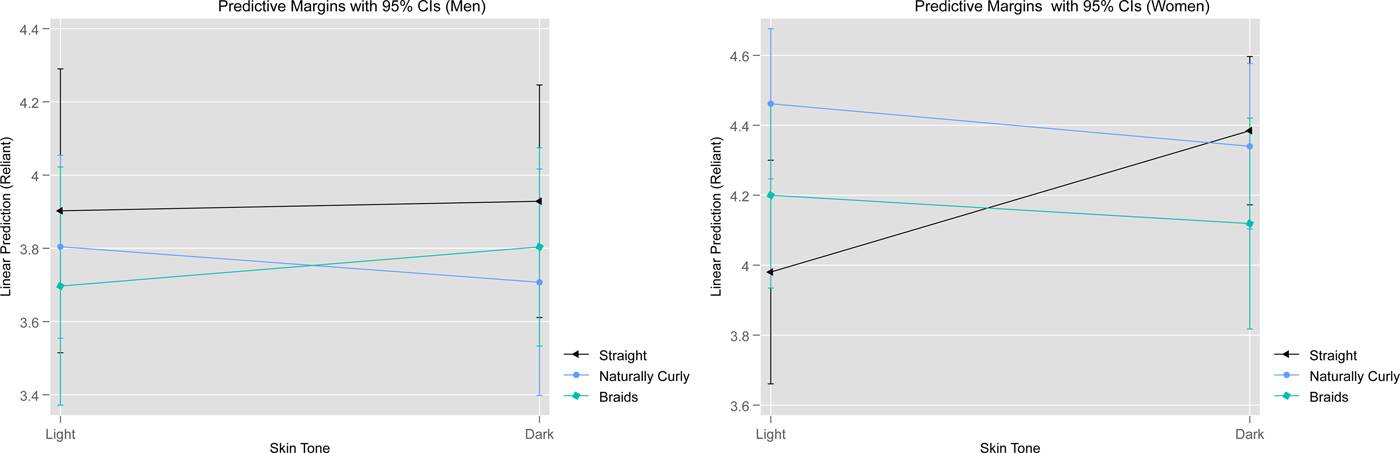

Likelihood of Voting

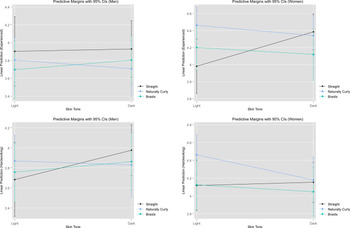

We begin with the likelihood of voting for Brenda Johnson. Recall that we expected the effects to go in either direction: on the one hand, Black men and women may engage in internal discrimination, and adhere to the negative stereotypes attached to Afrocentric features and be less likely to vote for Brenda Johnson as she becomes darker with less straight hair. On the other hand, Afrocentric phenotypes may empower Black respondents, particularly Black women. We do not find statistically significant effects of phenotype on voting for men and women, but we do see differences in the direction of the effects. In Figure 1, we illustrate the predictive margins of the interaction between hair and skin with 95% confidence intervals. The results are not statistically significant, likely due to the small sample size. For men, we find support for the internal discrimination hypothesis. Among men, when hair is straight, we find that darker skin has a positive effect on the likelihood of voting for Johnson, but it is not statistically significant (.39, p = .305). When skin is light, we find that naturally curly hair also has a positive effect (.12, p = .740) as do braids (.17, p = .642). The interaction, however, has a non-statistically significant negative effect on men. Men are less likely to say they would vote for Johnson when her hair is curly and her skin is dark (−.42, p = .406), and when her hair is braided and her skin is dark (−.60, p = .247).

Figure 1. Reported likelihood of voting for Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

By contrast, among women, we find support for the empowerment hypothesis. When hair is straight and skin is dark, Black women are more likely to say they would vote for Johnson (.06, p = .840), as well as when skin is light and hair is naturally curly (.14, p = .678), but not when her hair is braided (−.31, p = .384). Unlike men, the interaction among women is positive. Instead, Black women are more likely to say they would vote for Johnson when she has dark skin and curly hair (.25, p = .573), and when she has dark skin and braids (.31, p = .510).

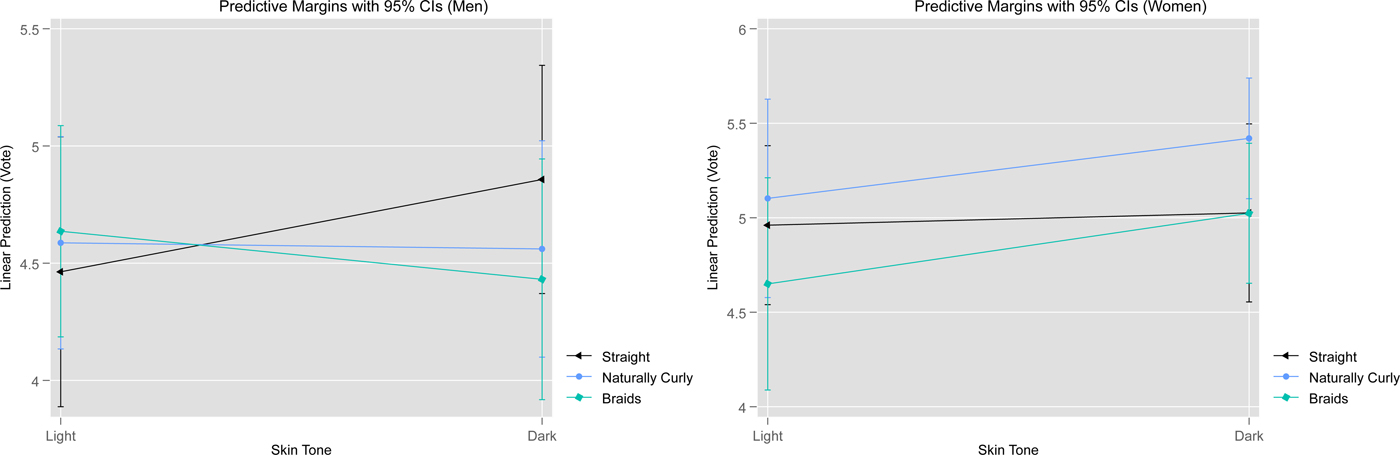

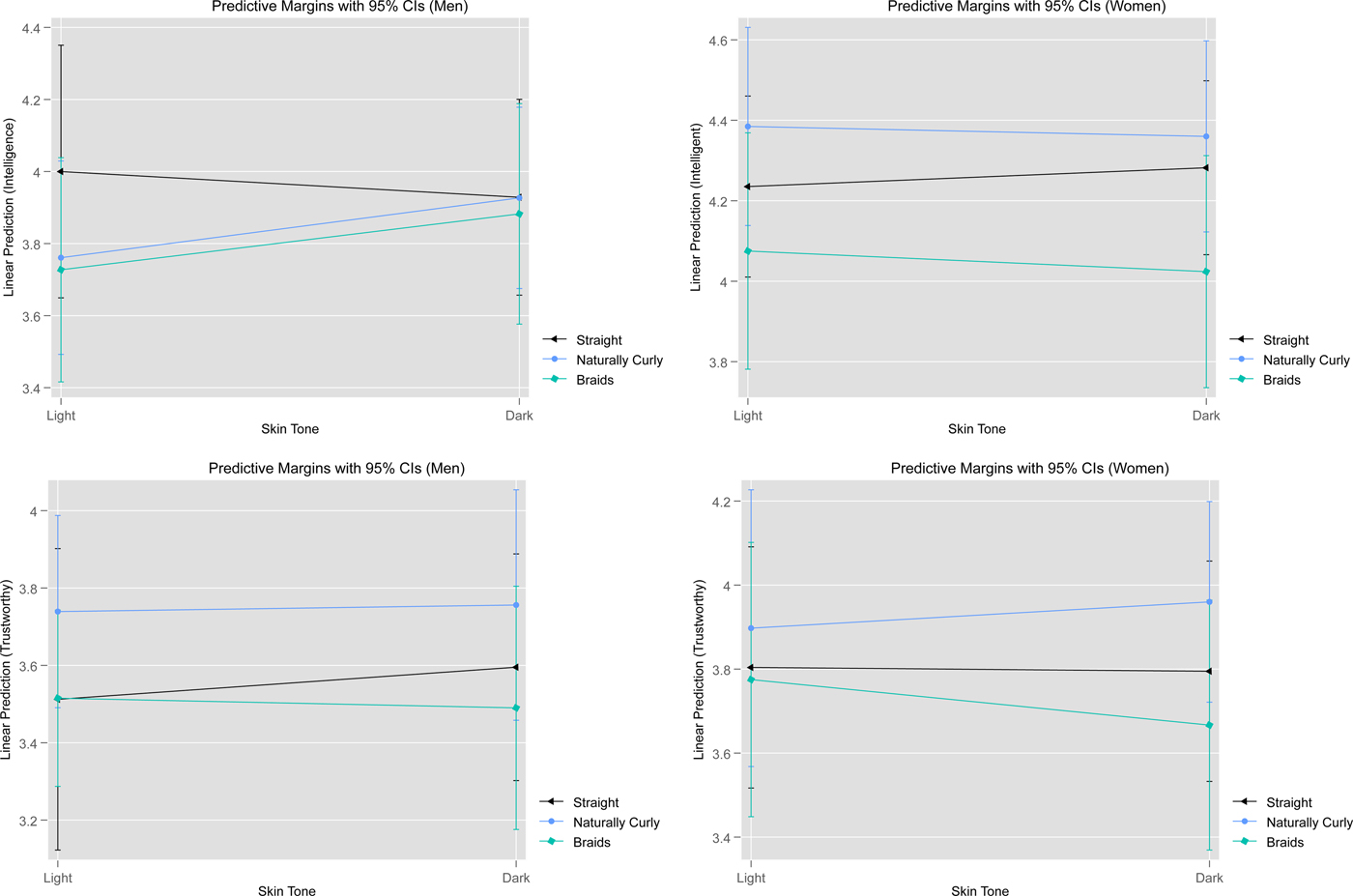

Trait Evaluations

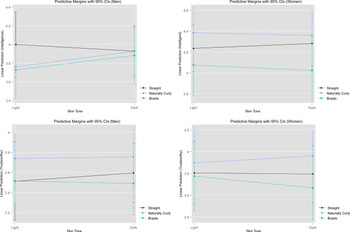

We asked respondents to rate how well various traits described Johnson: experienced, hardworking, trustworthy, intelligent, qualified, warm, compassionate, and able to compromise. We also asked about traits that represent stereotypes of Black women: resilient, uncontrolled, and reliant (Hicks Reference Hicks2017.) As with voting, many of our results do not reach statistical significance, and we find mixed support for the empowerment hypothesis and the internal discrimination hypothesis. For example, in the top panel of Figure 2, among men, regardless of phenotype, average ratings of Johnson as experienced are relatively stable. By contrast, women rated Johnson as statistically significantly less experienced with dark skin and naturally curly hair (−.53, p = .039), and marginally significantly less experienced with dark skin and braids (−.49, p = .087), supporting the internal discrimination hypothesis. Yet dark skin, holding hair straight, appears to have a statistically significant empowering effect on Black women (.40, p = .039). This suggests that the positive effect of dark skin on women is counteracted in the presence of curly or braided hair.

Figure 2. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

In Figure 3, both men and women also tend to view Johnson as less hardworking when her phenotype is more Afrocentric. Again, while dark skin appears to have a positive effect on both men and women, that trend becomes negative when hair is curly and braided. When asked about Johnson's trustworthiness, men view her as less trustworthy with darker skin and non-straight hair. Interestingly, among women, dark skin has a negative effect on trustworthiness ratings when hair is straight (−.009, p = .963), as do braids when skin is light (−.03, p = .896). Women view Johnson as more trustworthy when skin is dark and hair is curly (.07, p = .802), but not when she has dark skin and braids (−.10, p = .740). Men and women diverge in perceptions of Johnson as intelligent: the combination of dark skin and curly hair (.24, p = .418) and dark skin and braided hair (.23, p = .474) have positive effects on men, consistent with the empowerment hypothesis. The effects are negative among women and consistent with the internal discrimination hypothesis (dark/naturally curly: −.07, p = .762; dark/braids: −.10, p = .709).

Figure 3. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

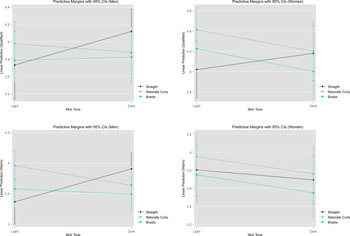

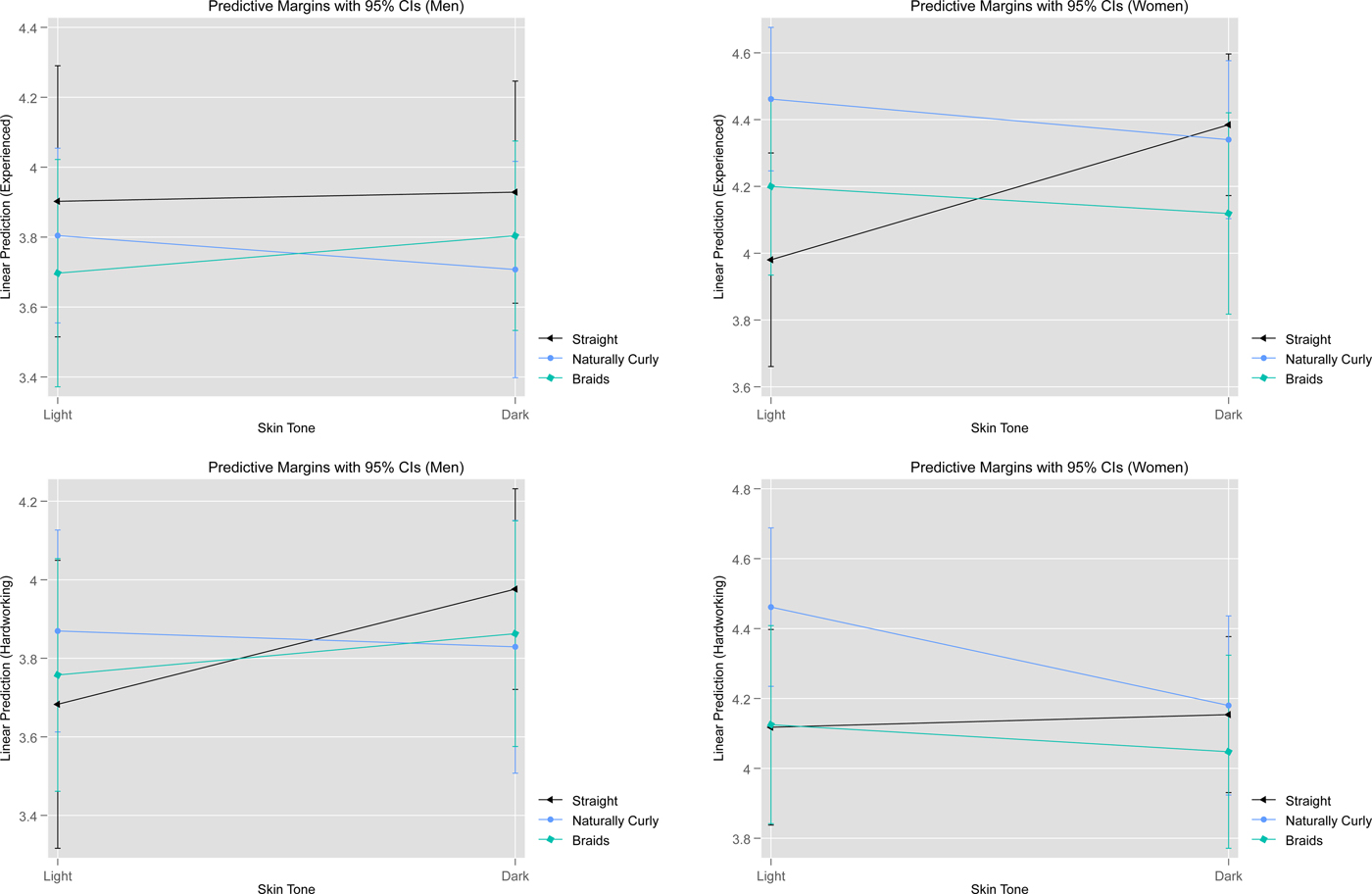

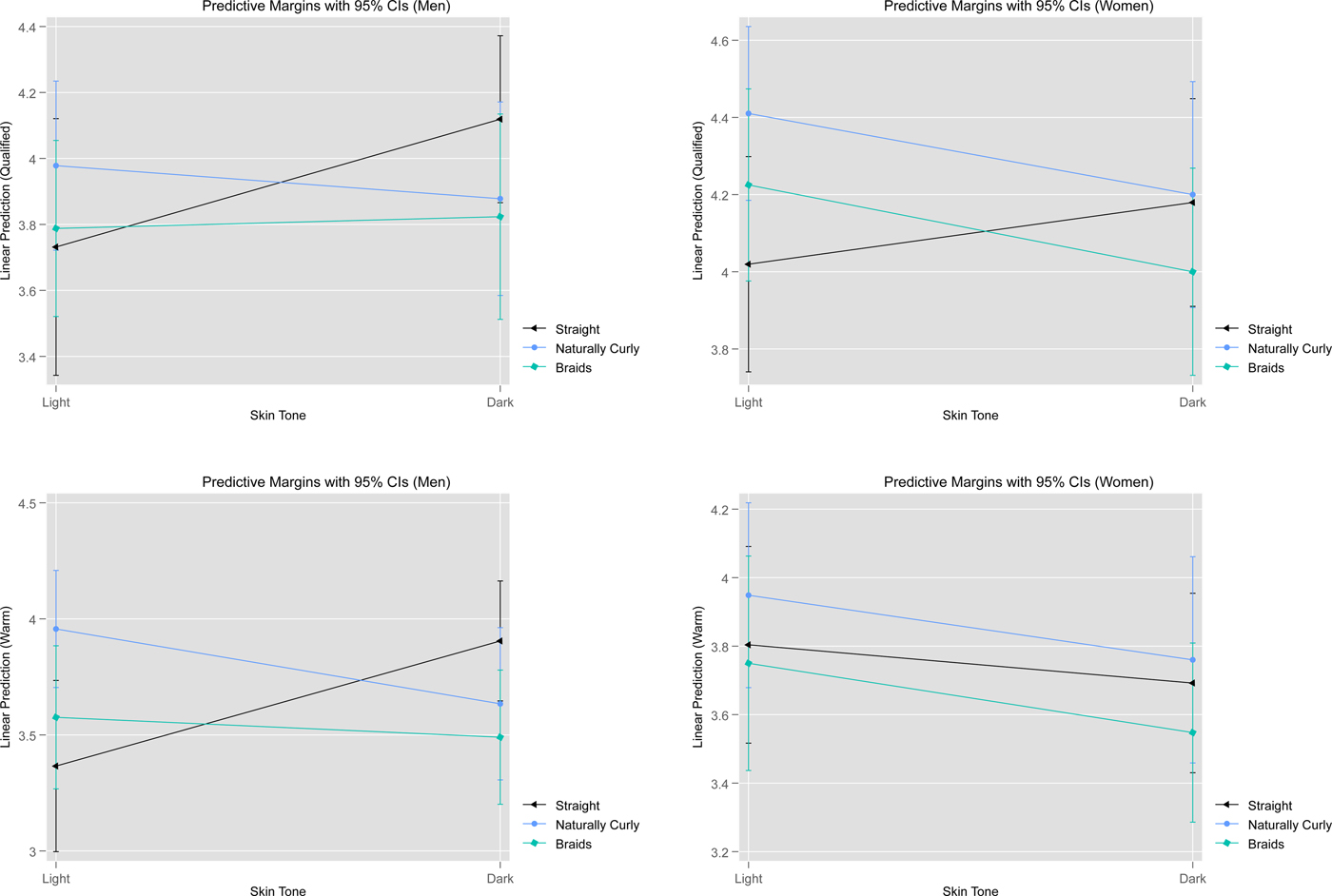

Figure 4 shows similar trends regarding hair and skin tone. The combination of dark skin and curly or braided hair has non-statistically significant negative effects on ratings of Johnson as qualified. Men also give Johnson significantly higher warmth ratings when skin is dark and hair is straight (.54, p = .019), as well as when skin is light and hair is curly (.59, p = .010). When hair is straight and skin is dark, women view Johnson as less warm, as well as when skin is light and hair is in braids. When skin is both dark and non-straight, women view Johnson as less warm. In Figure 5, both men and women view Johnson as less compassionate and less able to compromise the more Afrocentric she becomes, and the effects are not statistically significant. The negative effects on perceptions of Johnson's ability to compromise appear to be driven by the combination of dark skin and non-straight hair.

Figure 4. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

Figure 5. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

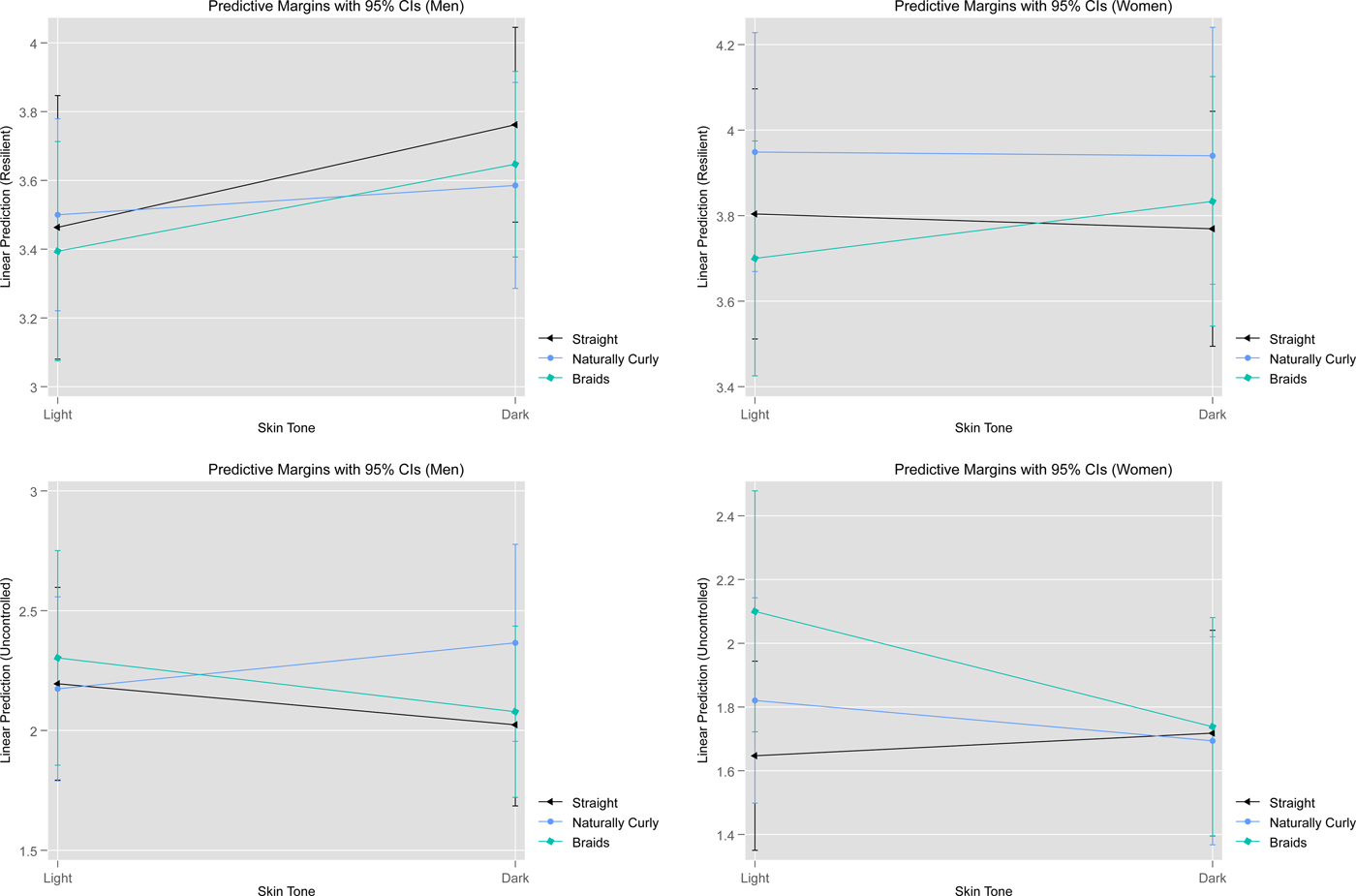

In Figure 6, men and women diverge. While men view Johnson as more resilient with dark skin and straight hair (.30, p = .219) and light skin and curly hair (.04, p = .15); she is viewed as less resilient with light skin and braids (−.07, p = .784). The combination of dark skin and curly hair (−.21, p = .505) as well as dark skin and braids (−.05, p = .888) also leads to lower ratings of Johnson as resilient. By contrast, the combination of dark skin and non-straight hair has a positive non-statistically significant effect on perceptions of Johnson as resilient among women (dark/naturally curly: .03, p = .929; dark/braids: .17, p = .560). As for ratings of Johnson as uncontrolled, men are less likely to view Johnson as such when she has dark skin and straight hair (−.17, p = .522), as well as when she has curly hair and light skin (−.02, p = .940). Among men, the combination of dark skin and curly hair boost perceptions of Johnson as uncontrolled (.363, p = .354), but they are less likely to view her as such when her skin is dark and her hair is in braids (−.05, p = .893). Among women, dark skin and straight hair, as well as light skin and non-straight hair, lead to the perception that Johnson is uncontrolled. The combination of dark skin and non-straight hair, however, has a negative effect on ratings of Johnson as uncontrolled. This suggests that Black women reject stereotyping a more Afrocentric-appearing Black woman as “uncontrolled” whether her hair is in curly or in braids, but Black men conform to this stereotype when Johnson is dark with curly hair.

Figure 6. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

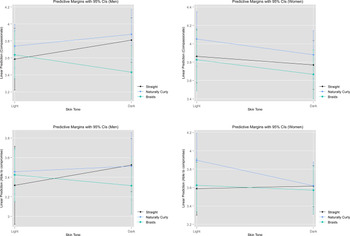

Finally, among men, in Figure 7 there are no statistically significant effects of hair and skin for evaluations of Johnson as reliant. By contrast, among women, dark skin, holding hair straight, has a significantly positively effect on perceptions of Johnson as reliant (.40, p = .039), as does naturally curly hair, holding skin light (.48, p = .015). Interestingly, the combination of dark skin and non-straight hair counteracts these positive effects, as women are significantly less likely to view Johnson as reliant when her skin is dark and her hair is curly (−.53, p = .039), and marginally statistically significantly less likely when her skin is dark and her hair is in braids (−.49, p = .087). Overall, the findings suggest support for the internal discrimination hypothesis and illustrate that the effects of hair and skin depend are interactive.

Figure 7. Trait evaluations of Brenda Johnson among men and women (hair × skin).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The findings of this study demonstrate the importance of an intersectional approach to gender and politics, as well as the import of Black feminist research on politics by paying special attention to the racialized and gendered interventions within body politics, American political culture, gender and racialized performance, and stereotypes about Black women. We show that the effects of hair and skin tone are interactive, and that hair texture is an important component of understanding how candidate appearance operates for Black voters. Our findings pose an interesting puzzle: why is it that Black men and women have negative impressions of a Black woman candidate with dark skin and natural hair, but Black women express a greater likelihood of voting for her? For insight, we draw on the battery of post-treatment variables that serve as our manipulation checks (see the Appendix). Recall that in darkening Johnson's skin and changing her hair, we sought to manipulate her perceived connection to Blackness. Our manipulation checks suggest that Afrocentric phenotypes, at least for Black women candidates, communicate a connection to Blackness, a propensity to represent Black constituents via liberal ideology and caucus work, but an inability to serve African-Americans, particularly for Black women. The combination of dark skin and natural hair was positively associated with perceptions of Johnson working with the Black Caucus for Black women, but negatively associated with such perceptions for Black men; Black women also perceived that Johnson would work with the Women's Caucus (Tables A21–A22). This suggests that our manipulation was indeed successful at making our candidate appear closer to Blackness. As minority candidates are often associated with liberal ideologies, Black women also tended to rate Johnson as more liberal in the dark skin/natural hair conditions, while Black men tended to rate Johnson as more conservative (Table A20). Our manipulation may have been more successful for Black women respondents. Puzzlingly, however, both Black men and women view Johnson as less likely to serve African-Americans in the dark skin/natural hair conditions (Table A16).

We hypothesize that for Black women, exposure to a more Afrocentric phenotype may activate a gender-race linked fate for action (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Philpot and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007). Voting is an action, and it is plausible that even if Black women tend to view the candidate as less experienced, for example, that they will not necessarily withhold their vote, absent all other information about the candidate. Furthermore, given Black women's tendency to reject the view that Johnson was “uncontrolled” in the dark skin/natural hair conditions—a stereotype often applied to Black women—we suggest that an internal politics of respectability (e.g., Jefferson Reference Jefferson2018) may be at play and may operate differently among Black women. In manipulating Johnson's closeness to Blackness, it appears we also manipulated her likeability. Feeling thermometer ratings of Johnson lend support to our hypothesis regarding respectability politics: Black women felt cooler toward Johnson in the dark skin/natural hair conditions (Table A19). Black women may have specific impressions of a Black woman candidate who wears her natural hair, but when it comes to voting, support is still possible. Thus, an interesting dynamic is at play among Black women: Black women voters may infer that a more Afrocentric candidate will advocate for their interests and thus vote for her, but they may also believe that the candidate will have a harder time as a leader given her Afrocentric phenotype. It is possible that Black women's responses to the candidate are a function of the combination of internalized racism and/or sexism. Ultimately, these findings offer fruitful opportunities to pursue further research on Black voters, specifically Black women voters. Focus groups with Black women voters are particularly promising to investigate these patterns more deeply.

Our findings differ from the extant literature in specific and meaningful ways. Terkildsen's (Reference Terkildsen1993) study on White evaluations of lighter and darker Black men candidates illustrated the complex relationship between prejudice toward Blacks (1,051) and the tendency to “self-monitor” (1,037), where the most prejudiced Whites without a filter expressed more support for a lighter-skinned candidate, while those with a filter inflated their support for a darker-skinned candidate (1,046). While we do not include measures of prejudice or self-monitoring in our study, we suggest that for Black respondents, racial prejudice and self-monitoring may not apply to evaluations of Black women candidates, as there is a descriptive representative element to evaluations of Black women candidates (i.e., Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; for an analysis of respondent skin tone and candidate skin tone outside the American context, see Ahuja, Ostermann, and Mehta Reference Ahuja, Ostermann and Mehta2016).

Our findings contrast with Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin (Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015), who found that Black conservative Democrats were significantly more likely to prefer a darker-skinned Black man candidate over a lighter-skinned one (64), arguing that Black Democratic conservatives use skin tone to infer Black candidates' issue stances as conservative (66, 74). Our sample characteristics and small sample size do not permit us to speak to the behavior of Black Democratic conservatives—the majority of Black women in our sample are Democratic (64.89%) and somewhat liberal (mean = 3.66, 1 = very conservative to 5 = very liberal). This ideological pattern is similar among Black men (mean ideology = 3.41), though fewer Black men are Democrats (39.37%). It is possible that Black women in this sample were “projecting” their ideology onto the candidate (Lerman and Sadin Reference Lerman and Sadin2016, 150, 153–54), but our sample is not large enough to thoroughly test this explanation. Still, this research suggests that Black women's support for Black women candidates may be conditional on phenotype.

Our findings also differ from Weaver (Reference Weaver2012), who hypothesized that White women would not discriminate against darker-skinned Black men candidates (170), and found that support for the Black candidate was highest when he was darker-skinned (179, 182). Weaver (Reference Weaver2012) suggested that “race and color are operating as a signal for female and liberal voters about … a compassionate/non-compassionate dimension” (185). It is possible that Black respondents use skin tone and hairstyle in this way as well, but we suggest that there is a tension in how skin tone and hairstyle are used among Black women. Perhaps dark skin and natural hair are used here to infer the candidate's ability get the job done, hence voting, as well as the candidate as a person, hence poor trait evaluations. We do not preclude the possibility that changing the candidate's phenotype changed a few independent variables relevant to our outcomes, such as the candidate's class, for example. It is also possible that changing the candidate's phenotype changed perceptions of partisan affiliation—Black men were more likely to say the Republicans were one of the groups Johnson worked with in the dark skin/natural hair conditions, and Black women were less likely (Table A24). Perceptions of Johnson working with the Democrats were more mixed (Table A23).

In terms of future research, we issue a call for more work on the effect of phenotype on the candidacies of women of color. To understand Black women's positions in American politics, we need to ask a different set of questions about their experiences running for office—in our view, that set of questions must consider raced-gendered appearances. Substantively, political scientists have used studies of women or racial/ethnic candidates to demonstrate how Black women candidates are viewed by voters (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Harris Reference Harris2014; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2010; Seltzer and Smith Reference Seltzer and Smith1991; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012). While most work takes racial and gender identities as a starting point of analysis, few critically investigate the embodiment of race and gender for Black women, and thus miss the dynamism of voters' opinions of Black women candidates. As such, examining the influence of gender on women's campaigns or race on Blacks' campaigns and elections provides only a partial picture of Black women's candidacies.

By exploring Black voters' opinions of Black women candidates’ physical presentations, this study illustrates how ethno-racial minority American voters respond to racial/gender diversity among office seekers. We might ask whether Black women's appearances provide a more complex and nuanced understanding of their raced/gendered identities impact their candidacies. It is possible that Black women's hair texture/style and skin tone open and close opportunities for their candidacies. Thus, this research on Black women office seekers pays special attention to how physical representations can impact their electability to public office.

Within the next three decades, the United States will become the first major post-industrial society to witness a population move from a White majority to a non-White majority groups. These changes in demographics pose many challenges and opportunities to the study of politics and political actors. By measuring voters’ preferences, this study of Black women candidates provides a more inclusive means for investigating how identity impacts political behavior.

ACLKNOWLDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Tiffany Barnes, Christina Bejarano, Stefanie Chambers, Pearl Dowe, Marcela Garcia-Castanon, Taneisha Means, the participant at the 2017 Annual Meeting for the American Political Science Association, and participants at the 2017 New Research in Political Psychology Conference for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Amy Lerman and participants at the 2017 and 2018 Annual Meetings for the American Political Science Association, as well as the anonymous reviewers who reviewed this manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.18