Introduction

With the development of modern transportation and globalisation, international migration has risen. By 2019, the number of international migrants (long-term foreign-born residents) reached 270 million worldwide (International Organization for Migration, 2019). International migrants are subject to multi-dimensional barriers in accessing health-care in their destination countries which can adversely impact their health (Legido-Quigley et al., Reference Legido-Quigley, Pocock, Tan, Pajin, Suphanchaimat, Wickramage, McKee and Pottie2019), including barriers shared across migrant and local communities (such as low health literacy and socio-economic disadvantage), and more migrant-specific factors such as entitlement to care, language barriers, discrimination, social segregation and lack of information (Jayaweera, Reference Jayaweera2010; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Shommu, Rumana, Barron, Wicklum and Turin2016; Kristiansen et al., Reference Kristiansen, Razum, Tezcan-Güntekin and Krasnik2016). Health-care barriers lead to delayed care, underuse of primary care services and preventive medicine, and overuse of emergency services (Lebano et al., Reference Lebano, Hamed, Bradby, Gil-Salmerón, Durá-Ferrandis, Garcés-Ferrer, Azzedine, Riza, Karnaki, Zota and Linos2020). It is important to understand what influences migrants' access to health-care in high-income countries which are favoured by migration influx (International Organization for Migration, 2019).

Compared to other age groups, timely access to health-care is particularly important for older migrants because they are at a greater risk of suffering from comorbidities, geriatric conditions and chronic conditions (World Health Organization, 2022). Additionally, these conditions may further hinder access to health-care by limiting physical and cognitive function. An analysis of literature surrounding older migrants' experiences found that the conflict between traditional beliefs and the environment, such as the conceptualisations of health-care, health literacy and language barriers, intertwine to affect their access to health-care services (Arora et al., Reference Arora, Bergland, Straiton, Rechel and Debesay2018). In addition, more practical and universal barriers such as lack of financial and information resources, declining mobility, transportation and limited service capacity also affect older migrants (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Guruge and Montana2019).

China is the third largest country of origin for international migrants (International Organization for Migration, 2019). The 2021 census in the United Kingdom (UK) recorded 445,000 foreign-born Chinese residents in England and Wales (Office for National Statistics, 2022); in the United States of America (USA), it is estimated that there were 3 million foreign-born Chinese Americans in 2019 (Budiman, Reference Budiman2021). Chinese migrants show a unique pattern of migration closely linked to the economic and political landscape in east and south-east Asia, e.g. many migrated from Hong Kong to the UK in 1960s and 1970s due to Hong Kong being a British colony and its rapid urbanisation (Baker, Reference Baker and Skeldon1995), while the economic reform in mainland China after the 1980s opened up the possibility of migration that did not exist before for mainlanders (Lau-Clayton, Reference Lau-Clayton, Allan, Jamieson and Morgan2014). Chinese people also share cultural beliefs and values distinct from other ethnic groups, such as collectivism and filial piety, which may impact the conceptualisation of health and responsibilities.

Although a migrant population with unique features, it is hard to specifically compare the health status or health-related behaviours of older Chinese migrants with the general population, as this group is often aggregated with other age groups, ethnicities and non-migrants in population-level surveys. The Public Health Outcomes Framework in England, from 2012 to 2017, reported lower than average health-related quality of life score for people aged 65 and older among Chinese people (UK Government, 2023). Compared to overall population results, a lower proportion of Chinese people aged over 55 reported having their needs fully met at their last general practitioner (GP) appointment in England's GP Patient Survey in 2023. In terms of overall satisfaction with primary care, older Chinese people reported less ‘very good’, ‘fairly poor’ or ‘very poor’ experiences; and more ‘fairly good’ or ‘neither good nor poor’ compared to the overall scores. The results are similar to those reported by other Asian ethnic groups (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and other Asian), but less satisfactory than answers from African and Caribbean backgrounds (Ipsos MORI, 2023). These data show that older Chinese migrants may be experiencing different levels of access and satisfaction to health-care services compared to average levels and to other ethnic groups; it is important to explore the situation and the reasons specifically to ensure equitable care for this population. While there have been reviews on health-care access barriers across ethno-cultural migrant populations (Berchet and Jusot, Reference Berchet and Jusot2012; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Shommu, Rumana, Barron, Wicklum and Turin2016; Sarría-Santamera et al., Reference Sarría-Santamera, Hijas-Gómez, Carmona and Gimeno-Feliú2016; Liem et al., Reference Liem, Natari, Jimmy and Hall2021), none have specifically focused on the older Chinese population.

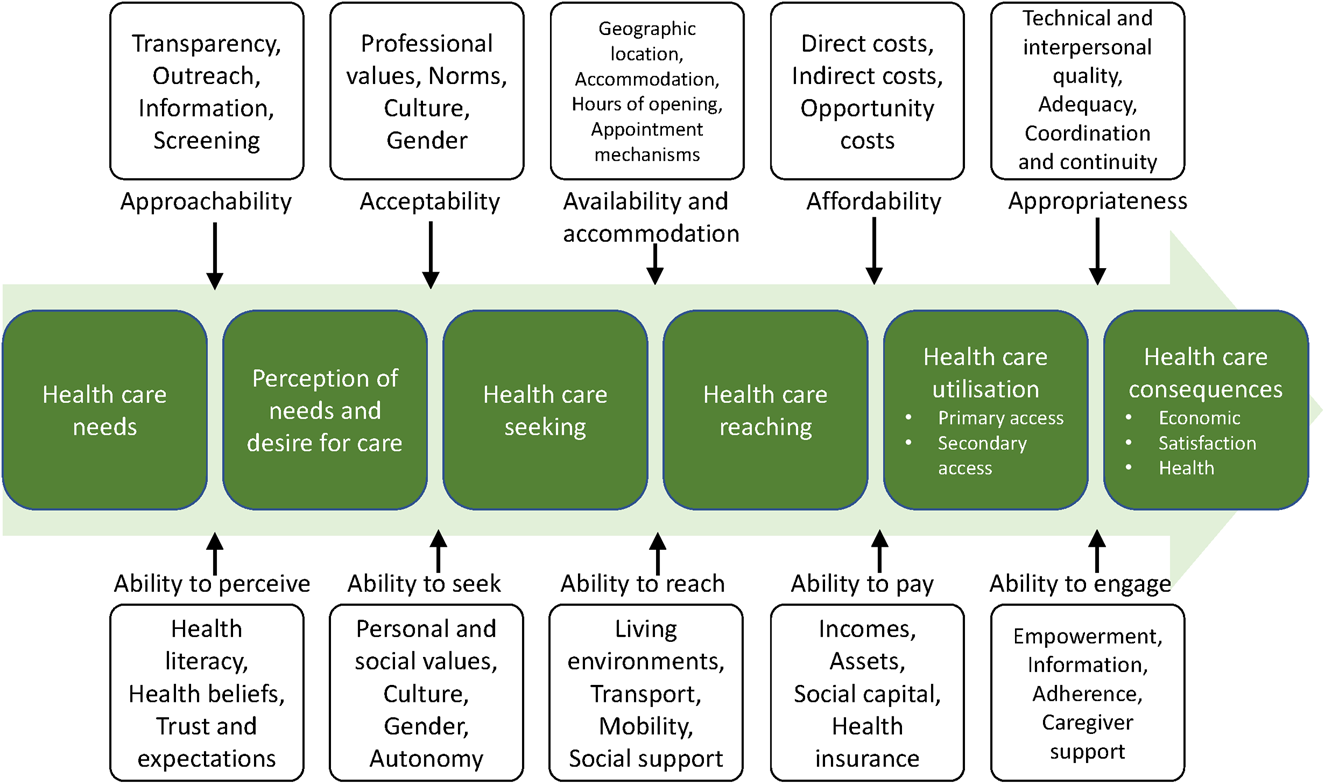

Health-care access has been conceptualised and defined in different ways. Levesque et al. (Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013: 8) proposed that a person-centred definition for health-care access is ‘the opportunity to identify healthcare needs, to seek healthcare services, to reach, to obtain or use healthcare services and to actually have the need for services fulfilled’. This pathway is influenced by both service and user characteristics. The service needs to have approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability and appropriateness; and the user needs the five abilities to perceive, seek, reach, pay for and engage with health services (Figure 1) (Levesque et al., Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013). Effective health-care access is a result of interaction between providers' and users' characteristics.

Figure 1. Levesque's framework of health-care access journey (Levesque et al., Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013).

The aim of this review is to analyse qualitative and quantitative literature to understand the barriers and facilitators to health-care access experienced by older Chinese migrants in high-income countries, using Levesque's health-care access framework. By focusing on a specific group, this review provides context and ethnicity-specific findings and recommendations for improving health-care access by Chinese migrants in high-income countries.

Method

A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies was carried out; the protocol was registered online (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021283501) (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Burns, Frost and Rait2021). Ethical approval was not required for this review; to ensure an ethical study, the authors reported on the methods and results accurately.

Search strategy

Literature was obtained from MEDLINE (Ovid version), Web of Science (all databases), EMBASE, Scopus, CINAHL Plus and ProQuest (ProQuest Central, Social Science Premium Collection and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global) with a structured search strategy. Searches were done on 6 October 2021; since trends in international migration have changed rapidly in the past two decades, only results after 1 January 2000 were extracted to retrieve the most relevant studies. Articles published in English from any high-income country were included.

The search strategy combined search terms in six fields: migrant population, Chinese, older people, access, health-care and health-care outcomes to form search strings; details are presented in Table S1 in the online supplementary material. Searches were carried out in the title, abstract and keyword fields, or title and abstract fields if keywords were not available. Controlled vocabulary terms were used to search MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL Plus; these terms are listed in Table S2 in the online supplementary material. This search strategy was built with the help of a librarian. Citation tracking of included studies was performed on Web of Science after the second round of screening to retrieve additional references.

Screening

Titles, abstracts and full texts were screened using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016), based on comprehensive screening criteria listed in Table 1 to identify studies which reported on factors associated with health-care access and utilisation by older Chinese migrants in high-income countries. A second reviewer carried out 10 per cent of screening independently. The two reviewers agreed on 90.5 per cent of results for title and abstract screening and 85.2 per cent for full-text screening; the Cohen's kappa was 0.51 and 0.53, respectively, indicating moderate agreement. Results were discussed for each round and all disagreements were resolved between the two reviewers.

Table 1. Screening criteria

Quality appraisal and data extraction

Studies that passed full-text screening were assessed with the appropriate Joanna Briggs Institute quantitative checklists (depending on study type) or the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies (Moola et al., Reference Moola, Munn, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Sears, Sfetcu, Currie, Lisy, Qureshi, Mattis, Mu, Aromataris and Munn2020; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2022). The qualitative and quantitative parts of mixed-methods studies were appraised separately. Where there was insufficient information for quality assessment, the author was contacted for more information. Studies that showed significant methodological shortcoming or incomprehensible results which made interpretation and analysis impossible were excluded (Kuo and Torres-Gil, Reference Kuo and Torres-Gil2001; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Harvey and Hoffman-Goetz2011; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Li and Dong2014).

Data were extracted using structured templates developed for this review (see Table S3 in the online supplementary material). The secondary reviewer verified 10 per cent of quality appraisal results and 10 per cent of data extraction results.

Data synthesis

Qualitative and quantitative data were synthesised separately. Qualitative data synthesis took a meta-aggregation approach to avoid out-of-context interpretation of qualitative results from different settings (Joanna Briggs Institute, Reference Aromataris and Munn2020). Themes from each study were collected and reviewed, alongside the quotes and explanations to support them. Similar themes were combined and categorised. Each category contains themes with related meanings; categories and themes are presented in the Results section.

Quantitative data were reviewed to collate factors associated with health-care utilisation. Given the various measures used in different studies, the quantitative data were not combinable, and thus were analysed narratively and categorised according to Andersen's behavioural model (Andersen, Reference Andersen1968, Reference Andersen1995), which was adopted by more than half of the selected quantitative studies. This model (Figure 2) depicts the interaction between environment, population characteristics, health behaviours and health-care outcomes. Population characteristics consist of predisposing, enabling and need factors; these factors influence health-care utilisation. Selected studies examined these three groups of factors under the population characteristics category and the health-care system under the environment category.

Figure 2. Andersen's behavioural model of health services use (phase 4) (Andersen, Reference Andersen1995).

Qualitative and quantitative results were reviewed after separate synthesis to generate descriptive themes for conclusion; these themes are supported by both qualitative and quantitative evidence. Qualitative and quantitative results relevant to each topic were compared; Table 5 shows the supporting evidence for each descriptive theme and how their concordance or discordance confirm or expand the theme.

Results

The search retrieved a total of 2,012 non-duplicate results; after two rounds of screening and citation tracking, 36 studies were included, 33 after quality assessment (Figure 3). Of the 33 studies, 15 were qualitative studies, 17 were quantitative studies and one was a mixed-method study. All quantitative studies and the quantitative part of the mixed-method study were cross-sectional.

Figure 3. Flowchart of screening process and results.

The majority (32) of studies used data from one of four countries: USA (N = 23), Canada (N = 4), UK (N = 4) and Australia (N = 1); one further study used data from both Canada and Australia. Sample size ranged between one and 78 for qualitative studies, and between 100 and 3,159 for quantitative studies. Most studies identified people aged 60 or over as ‘older’, except for several studies on screening tests which included participants aged 50 or over (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Yuan, Mandelblatt and Pasick2004; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Harvey and Hoffman-Goetz2011; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014). Only one study recruited participants aged 45 and over; however, most participants were over 65 in this study, so it remained relevant to the topic (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Tom, XinQi and Dong2017). Two qualitative studies also collected family members' and non-family carers' views alongside those of older Chinese migrants; these data were also extracted to support the themes (Aroian et al., Reference Aroian, Wu and Tran2005; Koehn et al., Reference Koehn, McCleary, Garcia, Spence, Jarvis and Drummond2012).

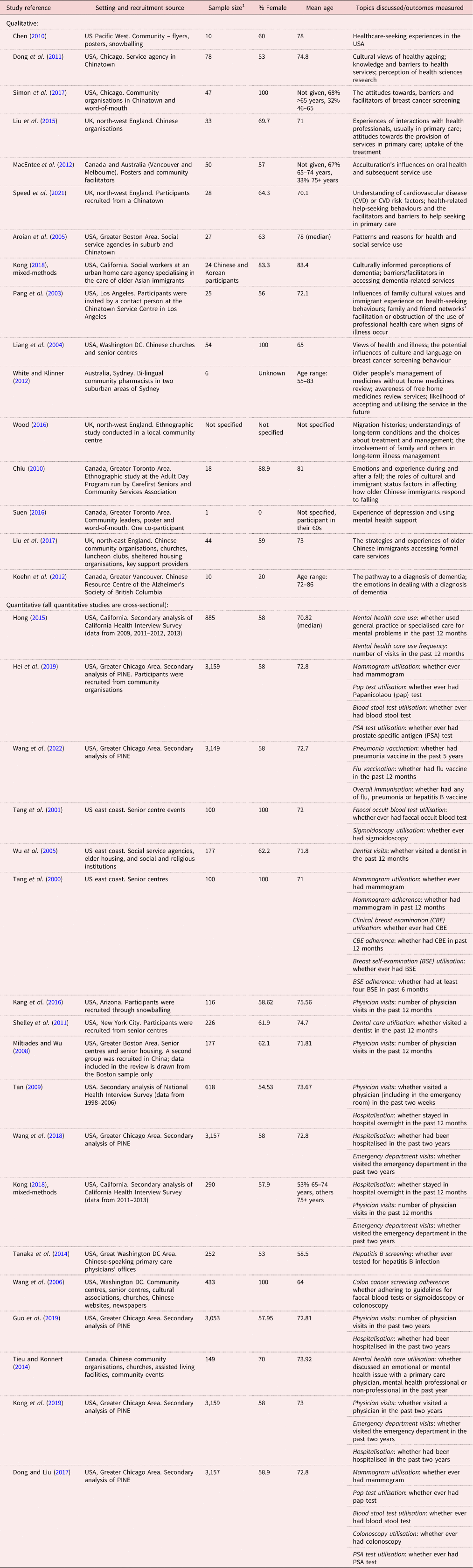

Services and health conditions covered by selected studies include non-specified care (hospitalisation, physician visits and emergency department visits for any reason), cancer screening, mental health care, hepatitis B screening, dental care, immunisation, home medicines review, dementia, falling and cardiovascular diseases. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of selected studies

Notes: 1. Older Chinese group only if the study has multiple groups. USA: United States of America. UK: United Kingdom. PINE: Population Study of Chinese Elderly.

Quality of selected studies

Details of quality appraisal are presented in Tables S4 and S5 in the online supplementary material. The qualitative studies were generally of good quality, with no study excluded on the basis of quality, but most lacked discussion of reflexivity.

The quantitative studies were also generally of good quality. Three studies were excluded due to serious concerns (Kuo and Torres-Gil, Reference Kuo and Torres-Gil2001; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Harvey and Hoffman-Goetz2011; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Li and Dong2014). One was excluded because it lacked detail on the data collection tool and the author avoided discussing counter-intuitive results (such as having insurance being associated with a 10-fold decrease in the likelihood of recent physician visits), suggesting there may have been a flaw in the analysis (Kuo and Torres-Gil, Reference Kuo and Torres-Gil2001). One study was excluded because the numerical results showed impossible values (Todd et al., Reference Todd, Harvey and Hoffman-Goetz2011). The final excluded study did not consider confounding; only conducting bivariate analysis (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Li and Dong2014). All quantitative studies were subject to recall bias due to measuring utilisation outcomes through participant self-report. The risk was higher for less-significant events like physician visits and lower for more-salient events like hospitalisation. Similarly, other self-reported variables such as family relations and adherence to screening guidelines could be biased by social desirability.

Qualitative findings

The qualitative findings identified factors related to health-care access in four categories: health-care systems, social factors, individual factors and health-care interactions. Themes under each category and the references supporting them are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Barriers and facilitators to health-care access identified from qualitative studies

Notes: USA: United States of America. TCM: traditional Chinese medicine.

In brief, older Chinese migrants are keen to compare the health-care system to that in China and are often frustrated by the referral process, long wait times and high costs that they encounter post-migration. Some older Chinese migrants also use traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) alongside modern medicine, which can lead to misconceptions about the safety and effectiveness of modern medicine.

Social network can play both positive and negative roles in health-care access. Members of older Chinese migrants' social circles, such as family, friends, neighbours and community workers, assist them in getting health-care, while needing help from family members could also be a constraint due to availability or feelings of burdening their family.

On an individual level, health knowledge, awareness of services, stigma and the cultural belief to avoid outsiders can impact on care-seeking attitudes and behaviours.

When interacting with physicians, some older Chinese migrants encounter obstacles during communication because of cultural and linguistic differences. A trusting relationship with the physician and the physician's recommendations and support are important for facilitating health-care access.

Quantitative findings

Quantitative studies assessed the utilisation of health care by Chinese migrants and the associated factors. No study measured satisfaction or access and utilisation of any form of digital or remote health-care.

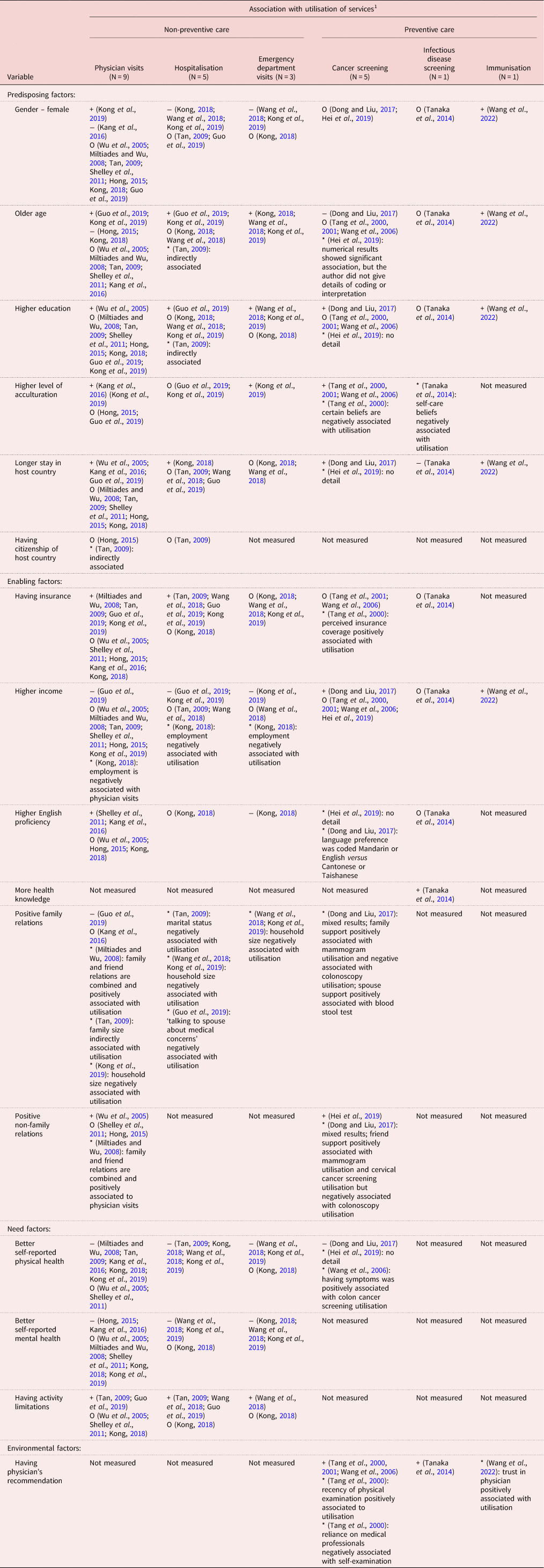

Two types of health care were analysed in quantitative studies: non-preventive care (N = 11, physician visits, hospitalisation, emergency department visits) and preventive care (N = 7, cancer screening, infectious disease screening, immunisation). The factors associated with these two types of utilisations differed and are discussed separately. Summaries of quantitative findings are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Significant and non-significant associations from quantitative studies measuring health-care utilisation

Notes: 1. + for positive, − for negative, O for non-significant, * for other (references in parentheses). Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018), Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019) and Kong et al. (Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019) used the same data source; Hong (Reference Hong2015) and Kong (Reference Kong2018) used the same data source; Dong and Liu (Reference Dong and Liu2017), Hei et al. (Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019) and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022) used the same data source. Dental care: Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005) and Shelley et al. (Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011); mental health care: Tieu and Konnert (Reference Tieu and Konnert2014) and Hong (Reference Hong2015).

All quantitative studies except one (Tieu and Konnert, Reference Tieu and Konnert2014) came from the USA, limiting generalisability. The one quantitative study from Canada examined help-seeking attitudes and mental health-care utilisation; it did not find a significant association (Tieu and Konnert, Reference Tieu and Konnert2014). Six studies analysed the same dataset, the Population Study of Chinese Elderly in Chicago (PINE study) (Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019; Hei et al., Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022) and so had similar findings.

Non-preventive care

Need factors (general health status, activity limitations and mental health) were the most significant predictors of non-preventive care utilisation. Having insurance was also associated with more health-care utilisation, except emergency department visits.

Among predisposing factors, the evidence of any association with physician visits was inconclusive for gender, age and education (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Tan, Reference Tan2009; Hong, Reference Hong2015; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019), but older age was associated with more emergency department visits (Kong, Reference Kong2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019).

Current evidence did not suggest a strong association between time since migration or acculturation with non-preventive care. Four out of ten studies found that longer residence in the USA was associated with more physician visits and hospitalisation events (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019), whilst two out of four studies found that a higher level of acculturation was associated with more physician and emergency department visits (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019).

Among enabling factors, having health insurance was significantly associated with more health-care utilisation among older Chinese migrants (Miltiades and Wu, Reference Miltiades and Wu2008; Tan, Reference Tan2009; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019). Kong et al. (Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019) found insured individuals had eight times the odds of having seen a physician and 1.5 times the odds of being hospitalised in the past two years than uninsured individuals. This association did not apply to dental care or emergency department visits (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019).

Language proficiency was only analysed individually in five studies (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011; Hong, Reference Hong2015; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018). Two studies suggested a positive correlation between higher language proficiency and more physician and dentist visits (Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016). Another suggested that lower language proficiency was correlated with more emergency department visits (Kong, Reference Kong2018).

Family and social relations were measured in only a few studies. Two studies using the PINE data found a negative association between the number of people in a household and more emergency department visits or hospitalisations (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019). As for physician visits, one study suggested that a smaller family size was associated with higher likelihood of having health insurance and US citizenship, which were then related to higher health-care utilisation (Tan, Reference Tan2009). Another study found an association between having negative family relations (reported feeling too much demand from family members and being criticised by family members) and more physician visits (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019). The evidence suggested older Chinese migrants with less family support tend to use more health-care.

One study, however, found that a higher frequency of seeing friends was associated with more dentist visits (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005). Another study measured family and non-family relations as one variable, and found it positively correlated with physician visits (Miltiades and Wu, Reference Miltiades and Wu2008). Two other studies that also measured non-family social relations found no correlation with mental health care and dental care utilisation (Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011; Hong, Reference Hong2015). Given the different characteristics of dental care, mental health care and general physical health care, there was not enough data to reach a conclusion about how non-family social support associated with health-care utilisation.

Among need factors, worse self-reported health and the number of chronic conditions were positively associated with all forms of non-preventive health care (Miltiades and Wu, Reference Miltiades and Wu2008; Tan, Reference Tan2009; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019), except dentist visits (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011). Having activity limitations (often measured by ‘do you have difficulty carrying out everyday activities’ or similar questions) was also positively related to all forms of health-care utilisation except dental care (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Tan, Reference Tan2009; Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sabbagh Steinberg, Dong and Tiwari2019). Worse mental health was also associated with higher use of emergency care and hospitalisation (Hong, Reference Hong2015; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kong, Sun and Dong2018; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Li, Wang, Davitt and Dong2019).

Preventive care

Evidence supported that the longer a Chinese migrant had resided in the current country and the more acculturated they had become, the more likely they would use preventive care. Physician's recommendation was also positively associated with utilisation.

Among predisposing factors, evidence was inconclusive for the association between health-care utilisation and demographics (age and gender) (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022) or education (Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017; Hei et al., Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022).

All studies examining preventive care explored the relationship between utilisation and time since migration or acculturation (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000, Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2001; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014; Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017; Hei et al., Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022). A longer time since migration predicted higher utilisation of cancer screening tests and immunisations (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006; Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017; Hei et al., Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022). More acculturated individuals were also more likely to engage with cancer screening (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000, Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2001; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006), but there was a significant negative association for hepatitis B screening (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014).

A few studies measured individual factors and their relationship with preventive care utilisation. Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000) reported that feelings of embarrassment during examinations or low perceived need for preventive care were negatively associated with breast cancer screening utilisation. Stronger self-care preferences were also associated with never having a hepatitis B test (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014). Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006) found that thoughts about getting cancer was a predictor for receiving colon cancer screening; while stronger Eastern cultural views (TCM beliefs and practices, fatalistic views of cancer, negative feelings towards Western medicine) were associated with lower cancer screening utilisation. These results supported that utilisation of preventive care was related to emotions and beliefs about illnesses and health-care.

Unlike non-preventive care, current evidence does not suggest that enabling factors such as insurance play a significant role in preventive care utilisation. Only one (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000) out of four studies (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000, Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2001; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014) found a significant association between insurance coverage and the use of preventive care, in this case mammograms. In the only study examining infectious disease (hepatitis B) screening, utilisation was positively correlated with knowledge of the hepatitis B virus (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014).

Having good social relations was positively correlated with getting cancer screening tests, but only for women (Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017; Hei et al., Reference Hei, Dong and Simon2019). Conversely, for colonoscopy utilisation, there was a negative association with receiving friends' support (Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017).

Among all the studies, only one examined need factors as defined in Andersen's model. This study found that those with more comorbidities were more likely to utilise cancer screening tests (Dong and Liu, Reference Dong and Liu2017). Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006) also found that being symptomatic was positively associated with receiving colon cancer screening; although at this point, the test was more diagnostic than preventive. There was insufficient evidence to conclude whether preventive care utilisation was associated with need factors.

Physician's recommendation of a test was significantly associated with utilisation, in all studies measuring this (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000, Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2001; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014). Recency of physician examination and reliance on medical professionals were also predictors of receiving clinical breast cancer screening tests (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000).

Trust in one's physician (measured by physician's dependability, confidence in physician's knowledge and skills, and confidentiality of information received) was positively associated with immunisation rate for flu and pneumonia (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022).

Discussion

Synthesis

Synthesising the qualitative and quantitative results demonstrates that the barriers and facilitators that play an important role in health-care access for older Chinese migrants are practical barriers, personal networks, perception of health needs and physicians' support (see Table 5).

Table 5. Qualitative and quantitative results supporting each integrated descriptive theme

Note: The frustration about different Chinese and Western health-care systems were discussed in some qualitative studies, but it is not clear how it influences health-care utilisation and is not explored by quantitative studies, hence it is not included in the descriptive themes.

The main practical facilitator for non-preventive health-care access in the USA is having insurance. The influence of health-care costs on health-care access and utilisation are likely to be different in countries with health-care free at the point of use such as the UK, and merits further exploration in different contexts. Other practical barriers such as transportation, time constraints and communication were not extensively explored in quantitative studies, but their importance was evident in qualitative studies of participants' experiences.

Personal networks and community make it easier for older Chinese migrants to access information and services, especially preventive care, as shown in both qualitative and quantitative evidence, although the relationship seems to vary with gender and the nature of medical conditions.

Perception of one's own health status determines the ability to perceive needs and seek help; it is influenced by beliefs, knowledge and health status. In qualitative studies, some themes touched on cultured beliefs and values such as preference for self-care (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Jordan-Marsh, Silverstein and Cody2003; Aroian et al., Reference Aroian, Wu and Tran2005; Chiu, Reference Chiu2010) and disease-associated stigma (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Cook and Cattan2017; Simon et al., Reference Simon, Tom, XinQi and Dong2017). A quantitative study that measured cultured beliefs of medicine and health also found traditional beliefs of medicine were associated with less cancer screening utilisation (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liang, Chen, Cullen, Feng, Yi, Schwartz and Mandelblatt2006). Understandings of the health-care system and awareness of services also determine whether formal health-care is deemed acceptable, appropriate and reachable for older Chinese migrants.

Physician's support is especially important for specialised care and screening since a primary care physician's referral is usually required for these services. Establishing trust between physician and patients is also important for encouraging the use of health-care services and increasing uptake of vaccines.

The qualitative and quantitative evidence diverge on one topic. Qualitative studies highlighted that family members play a significant role in accessing health-care for older Chinese migrants, although needing family's help can be a constraint. On the other hand, quantitative evidence suggests a negative relationship between good family relations or larger family size with health-care utilisation. These differences could reflect the conflict between wanting external care and wanting demonstration of filial piety mentioned in one of the studies (Aroian et al., Reference Aroian, Wu and Tran2005). It is also possible that older Chinese migrants like to seek help from their personal network before going to professionals (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Jordan-Marsh, Silverstein and Cody2003; Aroian et al., Reference Aroian, Wu and Tran2005; Chiu, Reference Chiu2010); informal options would therefore exhaust quicker when family relations are worse. More studies are needed to explore how family relations shape health-care behaviours for older Chinese migrants.

Acculturation measured by the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale, which includes language preferences, identity, friendship choices, behaviours, generational/geographic background and attitude (Suinn et al., Reference Suinn, Ahuna and Khoo1992), was analysed in some quantitative studies; increasing levels of acculturation was associated with more preventive care utilisation (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2000, Reference Tang, Solomon and McCracken2001). However, since these items were not analysed separately, further exploration is warranted to identify which aspects of acculturation are most significantly related to preventive care utilisation.

Figure 4 summarises these factors within Levesque's framework of health-care access.

Figure 4. Factors influencing access to health care for older Chinese migrants at the interface of user and provider. Framework by Levesque (Levesque et al., Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013).

Universal and unique factors influencing health-care access by Chinese migrants

Many of the barriers and facilitators for health-care access discussed here, such as language, social networks and cultural differences, have been reported in other migrant groups and are likely to be universal to all migrants (Alzubaidi et al., Reference Alzubaidi, McNamara, Browning and Marriott2015; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Shommu, Rumana, Barron, Wicklum and Turin2016; Arora et al., Reference Arora, Bergland, Straiton, Rechel and Debesay2018). However, the nuances are different for each migrant group and some facilitators and barriers are specific to Chinese migrants and their cultural beliefs.

For example, older migrants from different ethnic groups all express the importance of their children in accessing health care; while providing practical support, receiving care from children was also culturally desirable to symbolise the reciprocity of care between parents and children (Arora et al., Reference Arora, Bergland, Straiton, Rechel and Debesay2018). For Chinese migrants, this also relates to the concept of filial piety; that caring for one's parents is a moral obligation that the children owe to their parents. As the results suggested, though family played an important role in access, its interaction with service utilisation was not straightforward. Some Chinese migrants expressed conflicts with accepting help from outside the family (Aroian et al., Reference Aroian, Wu and Tran2005), and different expectations that can cause issues between first-generation migrants and their children or grandchildren (Baker, Reference Baker and Skeldon1995; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Tribe and Hui2010). Different underlying cultural beliefs could lead to different levels of preference for family involvement; understanding the value of filial piety is an important step towards understanding the complex role of family in health-care for Chinese migrants.

Another example is medical pluralism, supported by quantitave and qualitative evidence in this review. Although the use of complementary and alternative medicine, including a wide variety of herbs, supplements and health practices, is observed in other ethnic groups (Ernst, Reference Ernst2000; Wade et al., Reference Wade, Chao, Kronenberg, Cushman and Kalmuss2008), TCM has unique impacts on Chinese people as it is still practised in China as an integral part of the health-care system (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Shin, Liu, Shang, Yamashita and Lim2012). Many Chinese people hence adopt the belief that TCM and Western medicine are complementary in a specific way; the body and health are also sometimes conceptualised through terms of traditional medicine (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Beaver and Speed2015; Wood, Reference Wood2016). However, as TCM is not part of the health-care system in Western countries, some older Chinese migrants have turned to self-medication or private TCM practitioners for additional treatments while receiving treatments of Western medicine (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Jordan-Marsh, Silverstein and Cody2003; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Burke and LeBaron2007; Wood, Reference Wood2016; Speed et al., Reference Speed, Sun and Liu2021).

Gaps and limitations in evidence

There is a lack of evidence from outside the USA (23 of the 33 studies were from the USA), especially for quantitative data (16 of the 17 studies were from the USA). No study from non-English-speaking countries was found, further limiting application beyond the context of the US health-care system and generalisability.

Although the search strategy set out to find literature on telemedicine, no relevant study was found. There was little research on older migrants and their interaction with digital health generally, regardless of ethnicity. Given the rapid digitisation of health care and many other services used in daily life, this is an emerging topic for exploration; in the era of internet and remote health-care, older people are easily excluded and overlooked (Davidson, Reference Davidson2018). Understanding what role technology plays in health-care access for older Chinese migrants is a direction for future research.

Another overlooked aspect of health-care access is patient satisfaction. Understanding satisfaction and patient experience gives a more comprehensive view of how and why which services are used. Some qualitative studies showed that satisfaction with past experiences of health-care influenced older Chinese migrants' future health-care decisions, however, there is no quantitative data to complement or contradict this.

There were very few studies focusing on immunisation and screening. Hepatitis B is very relevant to Chinese migrants because the prevalence of hepatitis B was high in China before the roll out of vaccines in the 1990s (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Bi, Yang, Wang, Cui, Cui, Zhang, Liu, Gong, Chen, Wang, Zheng, Wang, Guo, Jia, Ma, Wang, Luo, Li, Jin, Hadler and Wang2009). This review found only two studies exploring hepatitis B screening and immunisation targeting the older Chinese population (Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Gehan, Chen and Wang2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li and Dong2022), a generation born before the vaccination campaign. Additionally, understanding the use of services for other infectious diseases, such as COVID-19 immunisation, are also important. In general, current evidence focuses on non-specific care and non-communicable disease prevention, especially cancer screening, with little focus on other health conditions.

Emergency department visits are utilised as a pathway to health-care by some older Chinese migrants who are unfamiliar with or frustrated by usual referral pathways. Given the limited number of studies that measured emergency department visits as an outcome, further investigation is needed on this topic to explore how it impacts health-care users and providers. These findings would be beneficial for reducing unnecessary emergency visits, in line with policy goals in the UK (National Health Service, 2019).

Most of the quantitative studies reviewed compared data within the Chinese ethnic group, with a few that compared different Asian groups (Tan, Reference Tan2009; White and Klinner, Reference White and Klinner2012; Hong, Reference Hong2015; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Kim2016; Kong, Reference Kong2018); these studies suggested different Asian populations had different characteristics, such as socio-economic status and levels of acculturation, which could relate to different barriers in accessing services. The only two studies which compared Chinese to non-Asian ethnic groups examined only dental care utilisation (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tran and Khatutsky2005; Shelley et al., Reference Shelley, Russell, Parikh and Fahs2011). Although focusing on one ethnicity is useful for drawing ethnic-specific results, there are few comparisons with other migrant or non-migrant groups in the same study. Such comparisons will be helpful for understanding which barriers and facilitators are shared across groups and which are specific to certain populations.

Given these gaps in current evidence, more research is needed to focus on ethno-culturally specific topics, emerging topics, comparison between sub-populations and in various settings, especially outside the USA, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of older Chinese migrants' interaction with health-care services.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This review is the first to focus on older Chinese migrants and their access to health-care in high-income countries covering literature published after 2000. Both qualitative and quantitative evidence was reviewed to give a comprehensive understanding of research findings in the field. Our results provide insights into the specific challenges older Chinese migrants face in their social and cultural context.

Due to limited resources, this review did not include literature published in languages other than English. Not all search results were double screened, however, agreement between reviewers was good.

This review focused only on patients' perspectives. Further evidence from other perspectives, such as health-care professionals' views, family members' views or a review of health-care policies would supplement the conclusions and provide a better understanding of what shapes health-care access for older Chinese migrants.

Implications for practice

With acknowledgement of the cultural context, efforts to provide more inclusive and culturally sensitive services will improve health-care access and benefit older Chinese migrants greatly.

Overcoming practical barriers would benefit not only older Chinese migrants but also migrant groups more generally. Language barriers could be overcome by providing information in different languages, clear signposting to interpretation services, improving the quality of interpretation and extending interpretation beyond clinical consultation (e.g. in pharmacies). More health-care resources and better management could reduce universal barriers such as wait time and travel time. Preventive care should be clearly recommended by physicians in a timely manner to improve uptake.

Health-care providers should acknowledge the commonly encountered barriers for this population, their preferences and beliefs, while acknowledging individual differences; this is especially important for those practising in areas with Chinese residents. Physicians should be proactive in discussing the use of traditional medicine and encourage communication by showing a non-judgemental attitude. Older Chinese migrants have particular issues in understanding and accepting the referral system. A clear explanation of the system would relieve concerns and help them access appropriate care pathways.

Given the role of social network for older Chinese migrants, attempts to involve family members and the local Chinese community in outreach and health education might help to raise awareness and remove obstacles to care. At the same time, efforts to remove practical barriers will enable older Chinese migrants to access health-care even when they cannot get help from family and friends.

More attention should be given to older migrants whose voices are often hidden or masked. Data on migration status or countries of origin are often not recorded in large-scale routine surveys. Given the history and complexity of international migration, ethnicity data, which are often captured, are not appropriate indicators for one's migration status. Distinguishing between migrants and non-migrants could provide a more accurate and nuanced understanding of health-care access and utilisation, especially for older people, who might face layered difficulties with service access.

Conclusion

This review has identified barriers and facilitators throughout the health-care pathway for older Chinese migrants, with a focus on patient perspectives. Perceptions of health, illness and health-care influence the realisation of health-care needs and the desire to seek care; they can either facilitate or hinder access. Transportation, wait time, financial cost and communication are practical barriers to reaching health care; social support is a facilitator during this process, while the involvement of family members can become a barrier. Lastly, the outcome of health-care is also influenced by the health-care environment, namely trust and support in a patient–physician relationship, and the structure of the wider health-care system.

Many ethno-cultural groups have different health-care beliefs that may impact on their interactions with health care, however, specific Chinese cultural contexts shape the nuances of barriers and facilitators for Chinese people. Health-care providers need to be communicative and respectful in creating a culturally competent environment to improve access for this population.

Health-care access for older Chinese migrants remains an understudied area. More research, especially those from outside the USA, on emerging topics, and focused on comparison between groups and sub-groups, will be important for providing evidence and improving equity in health care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X24000242.

Author contributions

HG, RF, GR and FB contributed to the conception and design of the work; HG and GA contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data; HG drafted the article; RF, GR and FB substantially revised the article.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required.