PROLOGUE

The back of the pickup bounced as we traveled north along the washboarded county road, dust trails swirling behind the truck's rear wheels and toward the sky. We looked to the horizon, where cedar-filled canyons and buttes marked the edge of the High Plains. Hints of green, in an otherwise yellow and brown landscape, gave evidence of seeps and springs—lifeblood for the people who thrived in this region for thousands of years. The three of us sat in silence contemplating this wide-open space and thinking of those people, and how they had made a living from such a place (Figure 1). Mike then spoke, gesturing to the northwest, “And there's Dipper Gap—Tom Pomeroy found that site while flying these canyons in his plane.” As we climbed the hill, the truck buzzed while crossing another cattle guard. Mike continued, “And over there is Flattop Butte, with well over 200 quarry pits—Clovis and Folsom peoples first discovered that chert over 13,000 years ago. And right there, that's ‘The Rocks,’ where Mary Carlson found a complete Upper Republican pot cached in that outcrop.” And the hours passed as we traveled miles of back roads looking over this broad patch of rural Colorado, sharing our knowledge of ancient Native American peoples and their lifeways.

Figure 1. Mike Toft standing near the Dipper Gap site in Logan County, Colorado. The High Plains meet the Colorado Piedmont here, in a land of buttes, cedar-filled canyons, and springs. (Photo courtesy of Mike Toft.)

This is a collective story, built over lukewarm coffee, on the tailgates of pickups, and in conversations lasting well into the night after community talks in local libraries—lessons learned from the many people who walked and studied the rangelands, dunes, and gravel bars of the High Plains of Colorado over the past 100 years. The three of us came together that day but having traveled there from very different places. Mike, an avocational archaeologist and farmer, had spent the last 50 years recording and collecting sites from his region, and he had a strong desire to share his findings. Jason, a college professor from the Great Plains, was trying to connect these sites into his encyclopedic landscape while also searching for the next project—for his own interests and his many students. And Marie, then a graduate student and now a career professional, wanted to see the Plains and make a positive impact not only in archaeological research but with her outreach as well.

This is our story of working together and making sense of the ancient history of the Plains. We think that professional archaeology, through both the pathways of academic and cultural resource management, has greatly added to our understanding of the past. However, history shows us that nonprofessional archaeologists have much to contribute to this narrative, especially in regions dominated by private property and lesser professional research activity. In this article, we share our thoughts on one small corner of the Great Plains and how we can learn more through collaboration and mutual respect.

NORTHEASTERN COLORADO: ABUNDANT ARCHAEOLOGY BUT LIMITED PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH

Colorado is a land of obvious contrasts. The mention of the state's name to outsiders might invoke images of snow-covered mountains, grizzled gold miners from the 1870s, and perhaps South Park—the long-running and irreverent animated comedy. But nearly half of Colorado is located within the western Great Plains, which through the end of the nineteenth century was a short-grass prairie devoid of trees except in scattered patches along perennial streams and rivers. The names of early railroad settlements, such as “Firstview,” hinted at those snowy peaks on the far western horizon (Wheat Reference Wheat1972), but those mountains were still days away by foot or wagon. And the only gold in eastern Colorado would be the limited water itself, which today is one of the most prized commodities in the region.

Eastern Colorado is mostly private property settled after the Homestead Act of 1862, with state lands scattered throughout these counties and originally set aside for rural schools. Other state lands relate to wildlife areas, with hunting and fishing still an important local recreation. Federal lands are minimal, mostly related to the Pawnee National Grassland, created following the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937. This act allowed the federal government to purchase failed homesteads from families who suffered greatly during the 1930s Dust Bowl (Worster Reference Worster1979).

Many of Colorado's rural communities appreciate local history, as demonstrated by the small museums scattered throughout the region. These county museums are typically jam-packed with material culture from the past 125 years, items from the town's history, old military uniforms, and faded photographs of early residents. Often an even earlier history is documented in the frames of arrowheads hung along the walls of these museums—a history more abstract and not as well understood by visitors. Arrowhead collecting (arrowheads, pottery sherds, spear points, and nearly everything in between) has been a widespread hobby for nearly 100 years in eastern Colorado. It is a way to physically connect with ancient Native American populations—by holding artifacts in your hands, you can imagine how they once lived on these same lands, these same spaces you now occupy. The irony of this history is easily lost, because the thrill of the discovery and the awe of the ancient technology does little to remind the finder that the descendants of these Native peoples exist today but are often far removed from their ancestral lands.

Today, cultural resource management (CRM) dominates American archaeology, in terms of conducting most of the site recording, testing, and excavation in the United States. CRM has expanded greatly in the past 50 years as an industry outgrowth of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966. However, CRM archaeology remains limited in eastern Colorado due to the lack of NHPA Section 106 work on private property and little federal land (the notable exception being the Pawnee National Grassland, which has experienced an exceptional amount of survey and test excavations over the past 50 years).

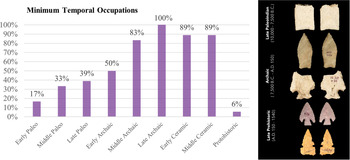

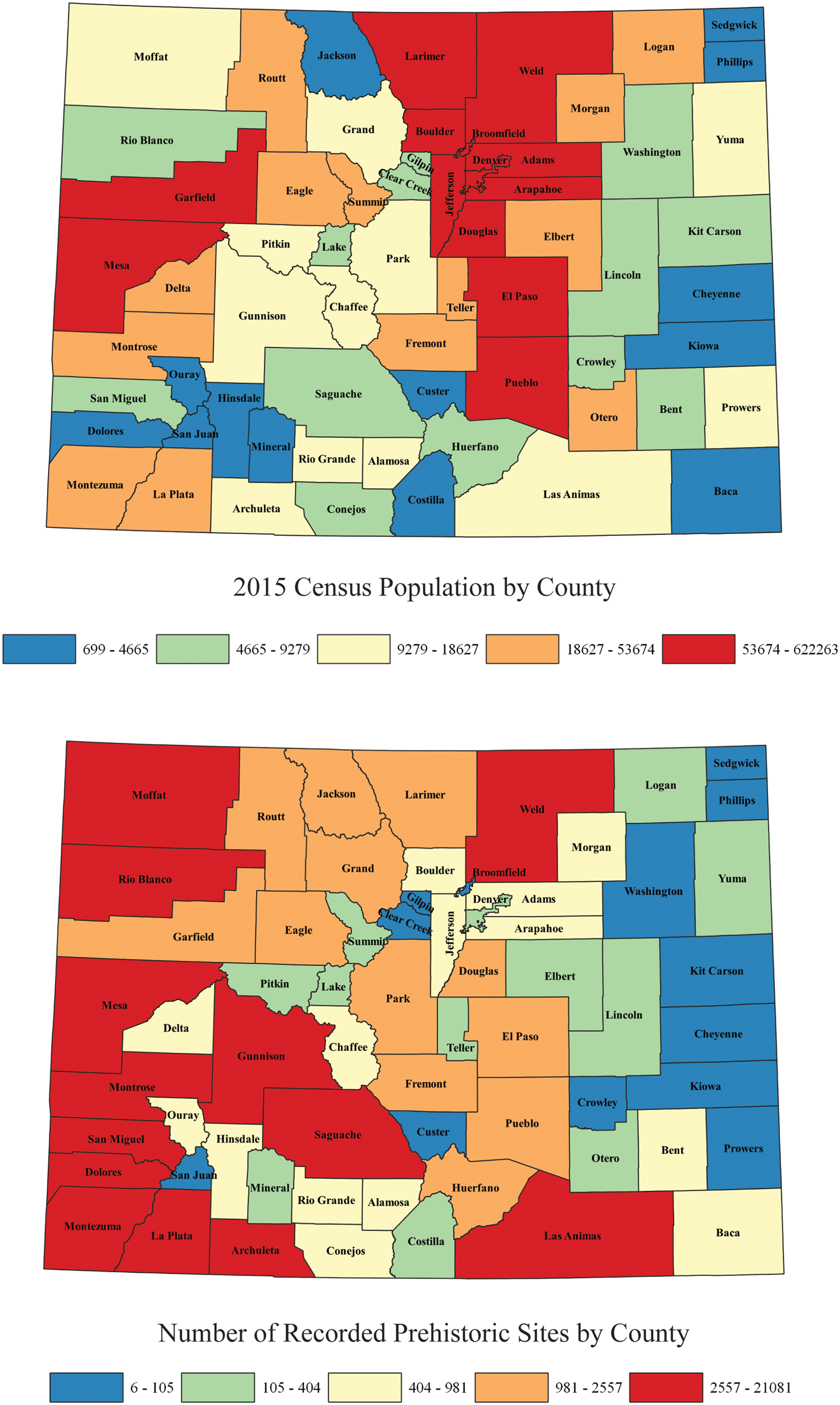

Given the lacuna in archaeological work, the prehistory of eastern Colorado would be enigmatic if not for ongoing efforts to record private collections. Large surface collections have been made over the past 100 years, and cultural historical sequences have been built by several research projects. However, many counties have seen limited professional investigation (Figure 2) due to minimal CRM research, lack of interaction with regional universities, and absence of local avocational society chapters, such as the Colorado Archaeological Society (LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003). This is especially so for those counties bordering Nebraska and Kansas, given their distance from population centers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Resident population of Colorado counties (2015) and the number of recorded prehistoric (ancient Native American) archaeological sites per county (Colorado Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation database, 2018).

We think that working with local artifact collectors remains one of the better ways for archaeologists to understand this region (Daniel 2016; LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003, Reference LaBelle2004a; Pitblado Reference Pitblado2014a, Reference Pitblado2014b; Shott Reference Shott2017; Shott et al. Reference Shott, Seeman and Nolan2018). The place is too large and too far from regional universities (for quick day trips to/from) to explore systematically. Locals have an intimate knowledge of this place, its resources, and how people have used this land for the past 13,000 years. As archaeology matures as a discipline, we must continue to develop new ways of fully accessing the archaeological record, and in doing so, ask new questions (Surovell et al. Reference Surovell, Toohey, Myers, LaBelle, Ahern and Reisig2017). We now turn to the distinctive ways that artifact collectors have documented this region over the past 100 years.

THE “WHERE AND HOW” OF ARTIFACT HUNTING

One of the many advantages of working with artifact collectors is that they often conceptualize and examine landscapes differently from professional archaeologists. For instance, access to land is of great concern to both groups. For most CRM archaeologists, this is often predetermined as the “area of potential effect,” or the project area slated for development. Paid work contractually occurs within that often narrow corridor. Collectors have a wider search strategy, selecting what they perceive to be ideal locations for finding sites and artifacts. The search is on once landowner permission is obtained. Favored locations for surface hunting, however, have varied over time with changes to local ecology and access.

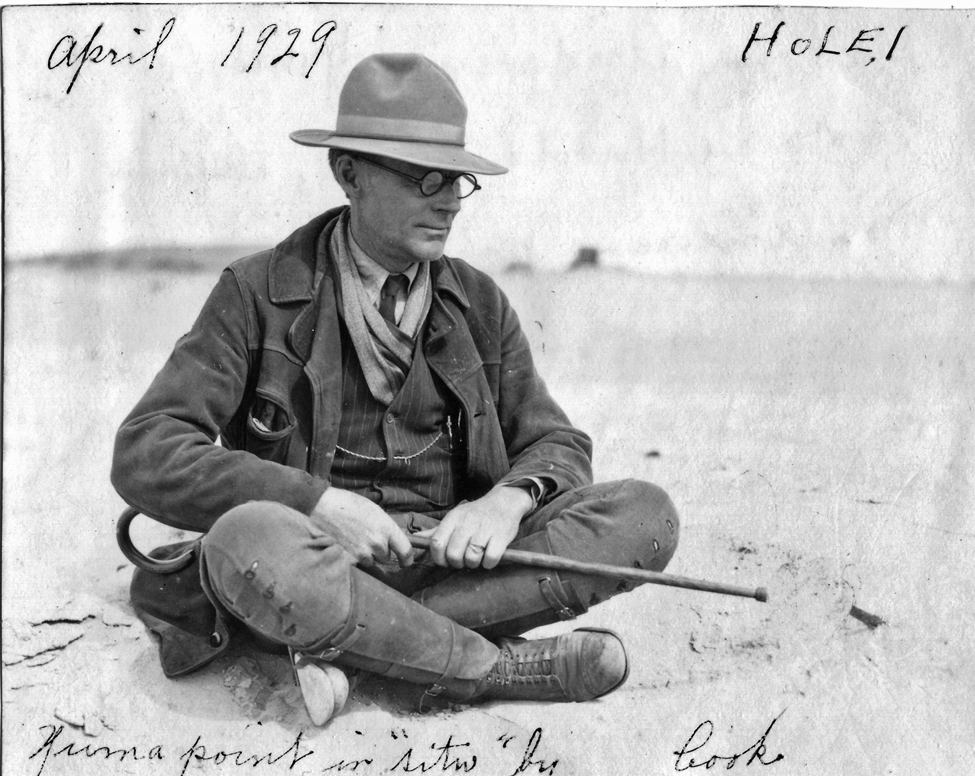

Many of the early artifact collectors loved searching the sandy country of northeastern Colorado, such as the famous dune fields of Yuma County (Muhs and Holliday Reference Muhs and Holliday1995). These sand sheets oscillated between erosion and stabilization over the past century, with notable periods of dune activation during the Dust Bowl (so-called Dirty 30s) and the late 1950s (the Filthy Fifties; Seebach Reference Seebach2006). The Dust Bowl profoundly influenced the history (and pace) of Paleoindian research in North America following excavation of the Folsom type-site between 1926 and 1928 (Meltzer Reference Meltzer2006).

A fervent quest began with the discovery of deep time at the Folsom site and the scientific revelation that these fluted projectiles were of great antiquity. Within a short time, people began reporting Folsom and other spear points to scientists across the country. But a perfect storm was brewing—the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl (Worster Reference Worster1979). The decade to come would turn arrowhead hunting into a passionate hobby for hundreds of families on the Great Plains, given that the Dust Bowl provided an erosive force that revealed ancient tools by the bucketful in some cases (Andersen Reference Andersen1988, Reference Andersen1990; Gebhard Reference Gebhard1949; LaBelle Reference LaBelle2005; Seebach Reference Seebach2006).

Yuma County was the epicenter of this buzz because the sand sheets quickly blew down to much older soils, exposing artifacts and Pleistocene fauna such as mammoth bone and teeth (Figures 3 and 4). Local families, such as Perry and Harold Andersen (father and son), shared their knowledge with Colorado archaeologists such as Harold Cook, E. B. Renaud, and H. Marie Wormington, as well as scholars who arrived from afar, such as A. E. Jenks of the University of Minnesota and Richard Snodgrasse from the American Museum of Natural History (Andersen Reference Andersen1988, Reference Andersen1990; Figgins Reference Figgins1934, Reference Figgins1935; LaBelle Reference LaBelle2005; Renaud Reference Renaud1931, Reference Renaud1932, Reference Renaud1934). For several decades, collectors spoke of the “Yuma Point,” a type coined from these dunes but now known to represent a diversity of unfluted projectile forms, such as Allen and Eden points (Gilmore et al. Reference Gilmore, Tate, Chenault, Clark, McBride and Wood1999; Kornfeld et al. Reference Kornfeld, Frison and Larson2010; Wormington Reference Wormington1948, Reference Wormington1957). Bert Mountain (the cousin of Harold Andersen) brought others to these dunes, leading the University of Colorado to excavate the Claypool site in the early 1950s—one of the largest Cody Complex sites ever discovered (Dick and Mountain Reference Dick and Mountain1960; LaBelle Reference LaBelle2004b; Stanford and Albanese Reference Stanford and Albanese1975).

Figure 3. Representative sample of the Andersen family collection (1920s–1930s) from the dune fields of Yuma County, Colorado (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2005). Collection housed at the University of Nebraska State Museum. (Photo by Jason LaBelle.)

Figure 4. Perry Andersen pointing to a “Yuma” point in situ at his Hole #1 site, Yuma County, Colorado, April 1929. (Photo by Harold J. Cook.) The point is a Scottsbluff spear point, removed in a block of sediment by Andersen. (Image courtesy of the University of Nebraska State Museum.)

The problem with most of these dune sites was that there was little context: 12,000-year-old tools could be found lying beside 1,000-year-old pottery and broken glass from the nearby 1880s homestead (Gebhard Reference Gebhard1949). Archaeologists were amazed at the sheer quantity and antiquity of tools coming from such contexts, but their research interests shifted elsewhere to better preserved (and stratified) Paleoindian sites such as the Lindenmeier site in Larimer County, excavated by the Smithsonian Institution from 1935 to 1940 (Wilmsen and Roberts Reference Wilmsen and Roberts1978). Furthermore, many of these dune sites eventually stabilized, either through return of natural vegetation following drought or through government-sponsored efforts such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). But sand sheets were just one of the places to look in eastern Colorado.

Farmers’ preparation of their fields provided another opportunity for searching for artifacts (e.g., Navazo and Díez Reference Navazo and Díez2008; Palumbo Reference Palumbo2015; Shott et al. Reference Shott, Tiffany, Doershuk and Titcomb2002). One of the more important variables in plow-zone archaeology relates to the methods used, such as moldboard plowing, tilling, and chiseling. The application of these various farming practices has changed over time, with farmers gaining better knowledge of soil and moisture retention, and recognition of how each technique affects how deeply soils are disturbed. For example, deep moldboard plowing makes the most impact, breaking sod and overturning the topsoil with each cycle of field preparation, whereas chiseling fields does less damage to soils because the method breaks up the soil but leaves the majority of previous crop residue as surface cover. Regardless of the method, these practices break up sediment, displace it horizontally and vertically, and leave it vulnerable to eolian erosion. In addition, the switch to fall-seeded winter wheat was also a significant factor in increased field exposure.

Many collectors talk about springtime windstorms, which could easily remove inches of sediment during a storm, particularly when using farming practices that removed most of the surface vegetation. Collectors sought these “blown fields,” where the topsoil had blown clear (metaphorically past the next county) and left older and more consolidated sediments in place along with heavier clasts such as stone tools. These blown fields could range from small exposures of a few acres to upward of hundreds of acres in size (Figure 5). Once that topsoil was removed, the blown field might expose a landscape of artifacts. Blown fields have a characteristic look, with a hardened erosion-resistant surface visible and surrounded by loose wind-blown sediment. On occasion, fields can blow down to older, previously buried paleosols that can reveal the potential age of artifacts in the blown field. Artifact collectors speak of searching for darker blue-black soils, which often relate to organic rich paleosols dating to the Late Pleistocene and containing the potential for Paleoindian artifacts (Gebhard Reference Gebhard1949). For instance, Grayson Westfall noticed rich soils in a blown field while casually driving on a county road in Elbert County, Colorado. Upon examining the field, he discovered an extensive 12,500-year-old Folsom site exposed in the field, which came to be known as the Westfall Folsom site (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Westfall and Westfall2002).

Figure 5. Land of sky and (no) grass. Making a pass in this eroded farm field, Logan County, Colorado. (Photo by Mike Toft.)

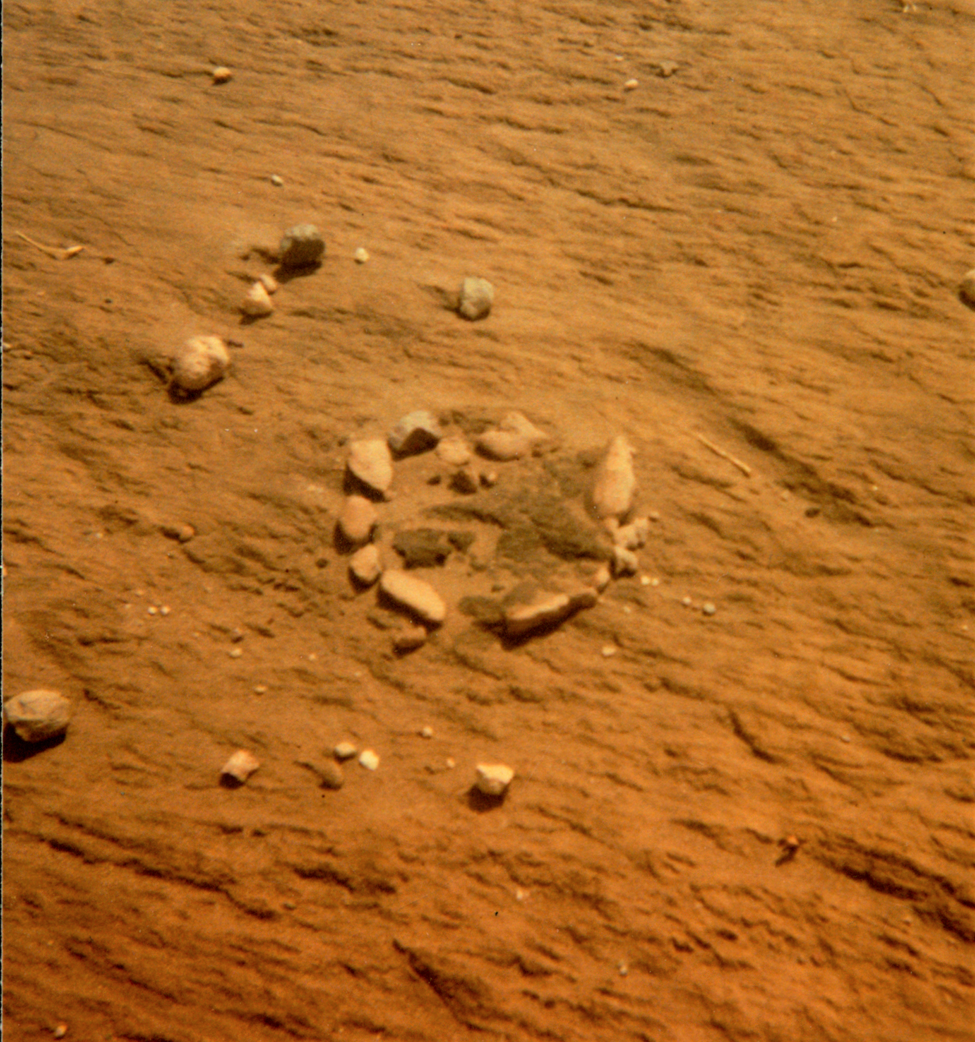

Mike's collection is made up of over 1,075 sites mapped and recorded from various private properties within the study area (Logan, Phillips, Sedgwick, Weld, and Washington Counties in Colorado; Chase and Perkins Counties in Nebraska). We refer to these as the “Toft” sites, based on Mike's last name. Many of these sites were found in deflated wheat fields as described above. Not only would flakes, pottery, and projectile points be exposed in such manner, but thermal features such as hearths (Figure 6) would be as well, demonstrating that archaeological deposits can remain in place in these sorts of contexts. Many collectors talk about the “good old days” of collecting agricultural fields, given that these sites could yield hundreds of tools, sometimes even in a day of collecting. But changes in tilling methods eventually led to lower rates of erosion, as have successful soil conservation programs.

Figure 6. Thermal feature exposed in eroded farm field, Logan County, Colorado. (Photo by Mike Toft.)

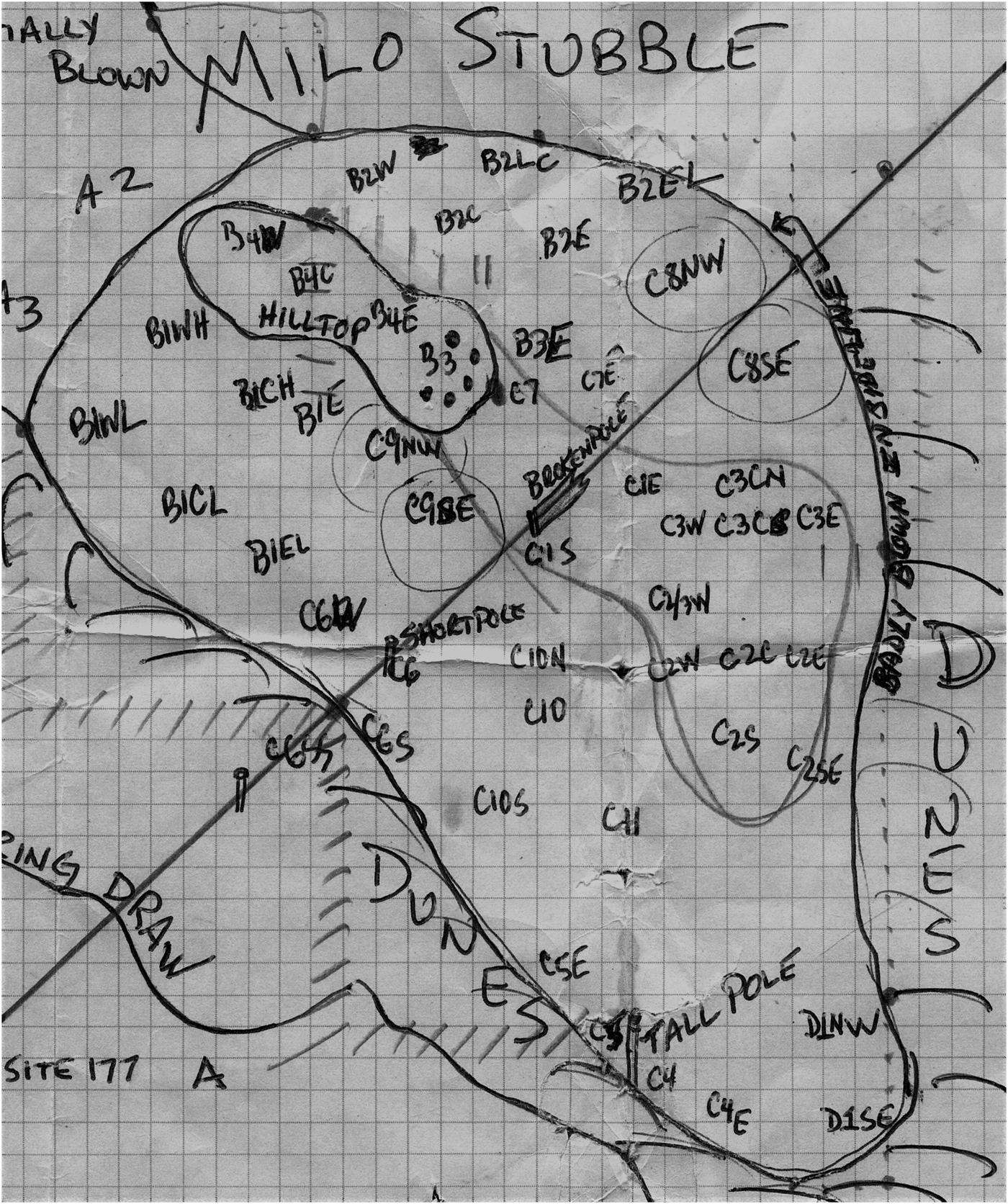

Mike fondly recalls a freshly plowed pasture that experienced extreme wind erosion beginning in 1978. This megasite (a cluster of many localities) was located southeast of Dipper Gap in Logan County and close to Flattop Butte (a major raw material source; Greiser Reference Greiser1983; Metcalf Reference Metcalf1974). The field was important to document for several reasons. First, the blown field was well hidden from roads in the region, so Mike had near exclusive access to surface hunt and map the site. The collection made from the site would be as complete as possible and not fractured between dozens of other collections in the area. Second, he had practical training in mapping and recording, so good records could be kept of the field finds and their locations. Third, Mike's new career as a dryland wheat farmer gave him the free time during the winter to get to this field after each blowing event. Time is of the essence for such sites in order to record them in their ideal exposure but before they are picked over by many other collectors in the region. From this site alone, he mapped over 40 separate “hot spots,” revealing thousands of stone tools and tens of thousands of pieces of debitage (Figure 7). Eventually, the farmer was able to regain control of the field (four years later) and plant it in grass, thereby ending surface collecting of this archaeologically important site.

Figure 7. Example of Toft's detailed map of an eroded farm field, noting numerous artifact localities spread across the archaeological landscape. Finds made within the past 20 years have been mapped with GPS technology. Site located in Logan County, Colorado. (Map by Mike Toft.)

Professional archaeologists might bemoan the potential loss of spatial association in such contexts through horizontal displacement via plowing and vertical deflation due to wind erosion. Indeed, the integrity of these sites is compromised through these site formation (or better yet, site exposure) processes. However, the potential benefit would be the exposure of an archaeological landscape over tens if not hundreds of acres. This simply calls for asking different sorts of questions of the archaeological record (i.e., issues of time perspectivism [Bailey Reference Bailey2007; Holdaway and Wandsnider Reference Holdaway and Wandsnider2008]), tailored to the dataset at hand, rather than pursuing the perfect, undisturbed site.

Additional areas sought for collecting included locations of varied topography and exposed geology (Figure 8). For instance, the “Chalk Bluffs,” made famous in James Michener's novel Centennial (“Chalk Cliff” in Michener Reference Michener1974), form a nearly straight boundary between the modern states of Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado. Two physiographic regions meet here: the High Plains and the lower Colorado Piedmont (Trimble Reference Trimble1980). This area contains cliffs, canyons, and buttes—and with it, rockshelters, springs, and raw material sources that ancient groups used intensively over the course of 13,000 years. This rugged landscape, in sharp contrast to the perceived monotony of the Great Plains, quickly draws the human eye. This broken terrain has yielded raw material stockpiles, biface caches, and even hidden pottery (Adams and Johnen Reference Adams and Johnen2015; Ellwood Reference Ellwood2002; Greiser Reference Greiser1983). Many of these rugged canyons have springs and pockets of juniper trees, which have drawn animals and humans to these sheltered places for thousands of years (Scheiber Reference Scheiber, Scheiber and Clark2008; Scheiber and Reher Reference Scheiber and Reher2007; Wood Reference Wood1967)

Figure 8. An ideal High Plains environment for hunter-gatherer occupation: the dissected valley of Lewis Canyon, Logan County, Colorado. Photo near the Donovan site (Scheiber and Reher Reference Scheiber and Reher2007). (Photo by Mike Toft.)

“River hunting” is another popular way to collect artifacts. Although river finds have been made for decades (Morris and Kainer Reference Morris and Kainer1975; Morris et al. Reference Morris, Lutz, Ted Ohr, Kloberdanz, Kvamme and Pool1975), river hunting became popular in the region during the late 1990s (e.g., Westfall Reference Westfall2002, Reference Westfall2007, Reference Westfall2011, Reference Westfall2019). In this scenario, collectors travel by canoe or kayak down river corridors such as the South Platte and stop along the river's gravel bars. Most trips occur after the high water of the late spring and early summer, when the river pulses with life. Collectors float gravel bar to gravel bar, searching for stone tools and faunal remains on the gravel. These items are clearly in secondary contexts, having washed out of banks upstream. But little local research has been conducted to see how far these items might be traveling (cf. Chauhan et al. Reference Chauhan, Bridgland, Moncel, Antoine, Bahain, Briant and Cunha2017; Chu and Hosfield Reference Chu and Hosfield2020) or searching for the original location of these displaced artifacts. Collectors have noticed that some gravel bars contain more artifacts than others. Is this a geological issue of artifact capture, areas representing locations of more intensive past use, or spots close to actively eroding cut banks containing this source material?

We will return to the significance of these collecting endeavors later, but artifact collectors are sampling landforms in eastern Colorado in ways that are far different from those of CRM or academic archaeologists. The preferred search locations have changed over time, mostly related to access to the land itself and how many artifacts could be found during a collecting trip. We now turn to a case study of eastern Colorado to demonstrate the unrecognized richness of these types of access to the regional archaeological record.

PLAYAS OF EASTERN COLORADO: A CASE STUDY

Playa lakes are one of the most prominent geographic features on the High Plains (Figure 9), with over 80,000 lakes dotting the tableland landscape from Texas to Nebraska (Bowen et al. Reference Bowen, Johnson, Egbert and Klopfenstein2010; Playa Lakes Joint Ventures 2019). Playas are circular, shallow depressions that seasonally fill with water and provide critical habitat for an array of flora and fauna (Haukos and Smith Reference Haukos and Smith1994; Smith Reference Smith2003). They have been characterized as “islands on the plains,” as isolated ecosystems that foster biodiversity in an otherwise homogenous landscape (Litwinionek et al. Reference Litwinionek, Johnson, Holliday, Kornfeld and Osborn2003).

Figure 9. Oblique aerial photo of a High Plains playa lake landscape. (Photo courtesy of Brian Slobe, Playa Lakes Joint Venture.)

This upland surface of the Great Plains is bison country. Hunter-gatherers followed their preferred prey onto these short-grass plains starting at least in the late Pleistocene. Playa lakes provided oases while occupying these uplands, offering access to predictable water, smaller game and waterfowl, and diverse vegetation (Haukos and Smith Reference Haukos and Smith1994; Litwinionek et al. Reference Litwinionek, Johnson, Holliday, Kornfeld and Osborn2003; Wedel Reference Wedel1963). Our understanding of playa use is well established in the Southern Plains, where archaeologists have built an extensive record of playa occupation (Brosowske and Bement Reference Brosowske and Bement1998; Hartwell Reference Hartwell1995; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Holliday and Stanford1995; Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Haynes, Hofman and Meltzer1994; Hurst et al. Reference Hurst, Johnson, Holliday and Butler2010; LaBelle et al. Reference LaBelle, Holliday and Meltzer2003; Mandel and Hofman Reference Mandel and Hofman2003; Turpin et al. Reference Turpin, Bement and Eling1997). However, little was known about how Native American peoples used these wetland landscapes in the Plains of eastern Colorado prior to our study.

A search of Colorado's Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (OAHP) archaeological database revealed only five archaeological sites known to be associated with playa lakes in eastern Colorado. This includes the Witzel site (5KC225) in Kit Carson County, a Cody Complex bison bonebed found by soil surveyors in the 1970s and reported by Dennis Stanford and the Smithsonian Institution (Bannan Reference Bannan1980; Cassells 1997; LaBelle and Holen Reference LaBelle and Holen2005). The Witzel site is in the center of a large playa basin and at its lowest elevation, suggesting Cody use of a dwindling or nearly extinguished water source. Stanford also conducted work on the Dutton (5YM37) and Selby (5YM36) sites in nearby Yuma County (Stanford Reference Stanford, Humphrey and Stanford1979). These sites are also situated within playa basins, containing megafauna such as mammoth, horse, bison, and camel, some of which have been dated to earlier than Clovis times. Although the mammoth bones were not found in direct association with any material culture, the bones were argued to have been broken through human agency. In addition, a chert flake and a Clovis point were found at Dutton, further connecting ancient peoples to this site (Stanford Reference Stanford, Humphrey and Stanford1979). Despite the few playa sites documented in the state database, Witzel, Dutton, and Selby suggest that ancient animals and humans utilized playas and that they likely played a large role in hunter-gatherer mobility systems in the region (LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Hurst and Hofman2010).

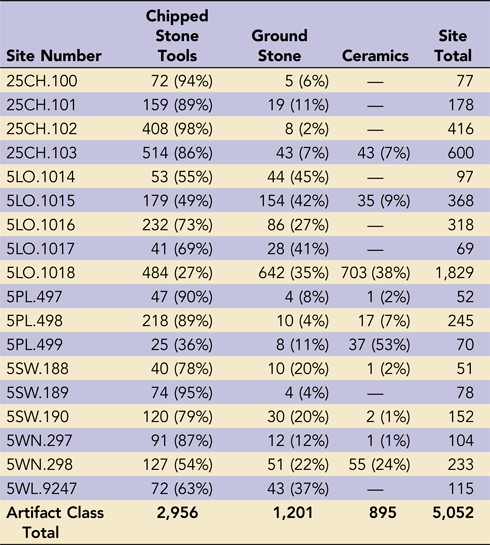

Although there are over 4,000 playa lakes mapped within northeastern Colorado alone, most of the playas are privately owned in areas where little academic or professional work has been undertaken. Therefore, working with avocational archaeologists is an important avenue for researching playa use and developing a more representative understanding of lifeways in the region. The lack of accessible property (and therefore sites) led to our case study, conducted by Marie for her graduate thesis research (Matsuda Reference Matsuda2021). Over the past 45 years, Mike recorded dozens of playa-associated sites across six counties in eastern Colorado and western Nebraska, ultimately providing 18 examples for Marie's project. In total, Marie analyzed 5,052 chipped stone tools, ground stone, and ceramic artifacts from these 18 playa sites (Table 1). Assemblage sizes for these 18 sites ranged from as little as 51 to as many as 1,829 artifacts per site. Importantly, this total does not include chipped stone debitage, which is by far the most common debris found on the region's archaeological sites. The analysis of these 18 locales reveals significant patterns of ancient Native American land use, suggesting much more intensive use of playa lakes in eastern Colorado as compared to elsewhere in the Great Plains.

Table 1. Playa Assemblage Composition for the 18 Toft Sites, Documenting Frequency (and Percentage) for Each Artifact Type.

Source: Matsuda Reference Matsuda2021.

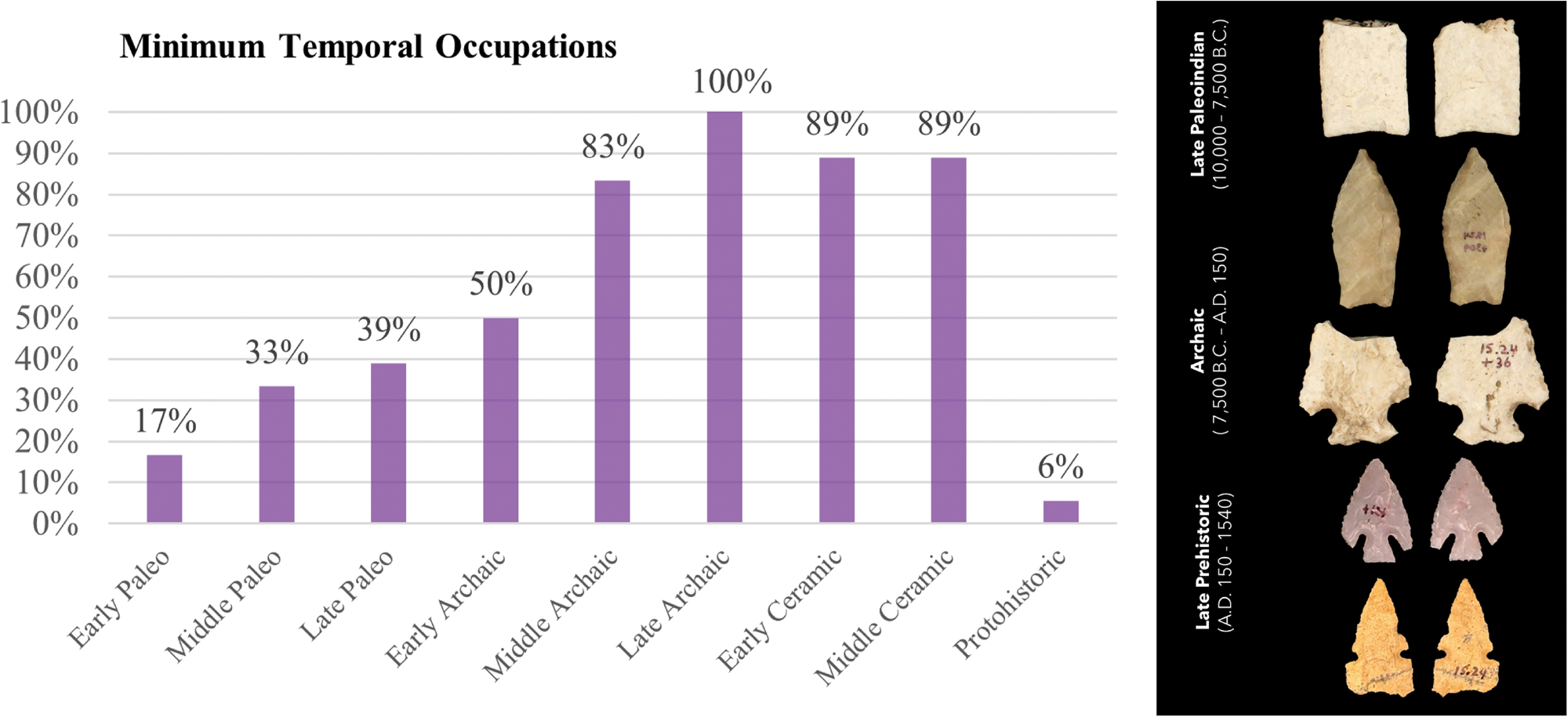

Many playa sites in the Southern Plains produced small assemblages that are often limited to formal chipped stone tools. For example, small bison and mammoth kills such as Miami, San Jon, and Winger have small assemblages with less than 10 total artifacts (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Holliday and Stanford1995; Holliday Reference Holliday1997; Holliday et al. Reference Holliday, Haynes, Hofman and Meltzer1994; Mandel and Hofman Reference Mandel and Hofman2003). The results from our case study demonstrate a very different record—that of a long and continuous history of playa utilization (e.g., Baker et al. Reference Baker, Campbell and Evans1957; LaBelle et al. Reference LaBelle, Holliday and Meltzer2003). All the Toft sites had evidence of one or more prehistoric occupations, with some sites being occupied during all periods, from the Early Paleoindian to the Middle Ceramic (Figure 10). The era with the most widespread evidence of Native American occupation is the Late Archaic (3000–1800 BP) period, and projectile points from this period were present at every site in the case study. The signature gathered from this small sample of playa sites demonstrates that the lakes were an important aspect of hunter-gatherer settlement systems for as long as people have occupied northeastern Colorado. Importantly, Marie generated site forms for each of these sites and submitted them to the Colorado and Nebraska State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs) as part of this thesis project.

Figure 10. Playa occupation by period for the 18 Toft sites (percent of sites containing said period), Eastern Colorado (Matsuda Reference Matsuda2021).

This case study highlights the importance of working with avocational archaeologists on research projects. Mike's continued monitoring and collecting of these sites produced robust, large assemblages that are unlike those typically seen in academic or CRM research. Often, a single recording is used to make evaluations of NRHP eligibility of an archaeological site. This is an understandable time/money issue, given that CRM archaeologists usually have but one chance to visit and record a site. Our case study not only tripled the number of known playa-associated sites in Colorado but also demonstrates that they were utilized intensively throughout time. This information could only be obtained through a methodical, longitudinal study of the region's archaeological record.

ARTIFACT HUNTING: HOW HAS IT CHANGED?

Much of what we share in this article is from our personal observations, and we argue that the topic of artifact collecting deserves to be more systematically studied (e.g., Kinnear Reference Kinnear2008; Nolan et al. Reference Nolan, Leak and Quimbach2018; Shott Reference Shott2017). But we offer here some of our thoughts on how artifact collecting has changed over the past 50 years in eastern Colorado.

Access to land has certainly changed for many artifact collectors. Years ago, much of the land was owned by local families. Chances were you personally knew the family or at least knew of them if you lived in the area. Artifact hunting was often allowed through simple handshake agreements, which gave locals permission to travel across and hunt lands for artifacts. The nature of rural communities has shifted, and many people have moved from these communities to seek work elsewhere. Small farms and ranches have consolidated into larger operations, leading to agricultural economies of scale often with absentee or nonlocal landowners. Consequently, access to these same lands has changed, with many ranches barring locals from these properties over worries of privacy, liability, and potential financial loss.

Soil and wildlife conservation programs have also done their intended job, and lands that were once easily erodible are no longer bare ground. Many farmers and ranchers are now better educated about preserving the ecological resources of their property, in terms of soil conservation, increasing bird habitat through living fences or hedgerows, and protecting riparian resources such as playa lakes on their properties. These ecological preservation improvements have led to fewer archaeological sites being exposed in agricultural fields, sand sheets, and drained playa bottoms.

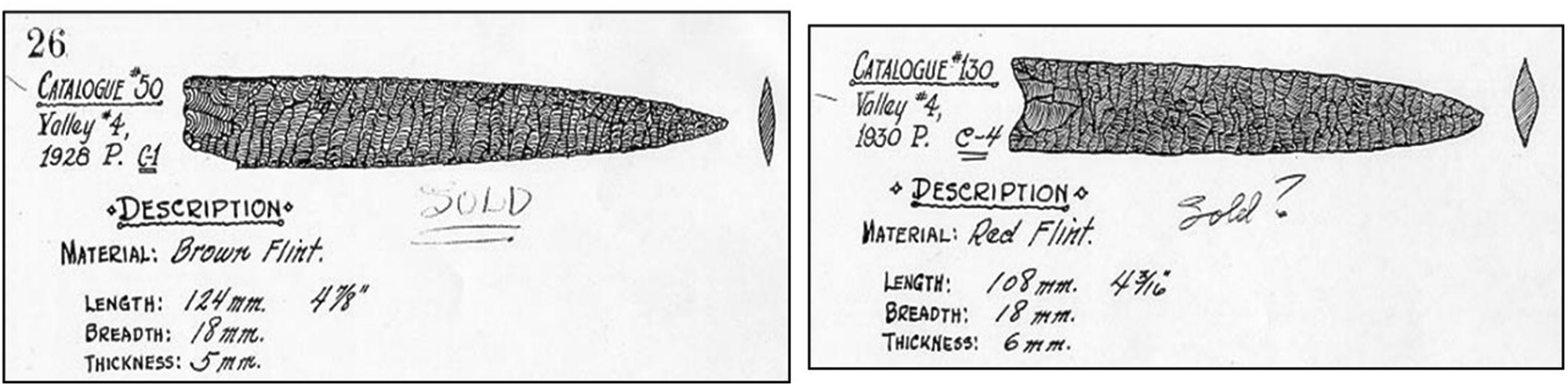

Artifact commercialization has also become an issue, leading to remarkably high monetary values for complete and rare items. However, the buying and selling of artifacts is not a new phenomenon to the Great Plains—the Andersen family sold select pieces of their “Yuma” collection in the 1930s, such as to the collector (and arrowhead book author) Virgil Russell (Reference Russell1945). This included the famous “Slim Arrow” spear point, one of over 65 points recovered from the Slim Arrow bison kill of the Wray dune field in the 1920s–1930s (LaBelle Reference LaBelle2002). From the Russell collection, those points and others traded hands again several times, moving to the Forrest Fenn collection, and now to another collection—gaining monetary value with each transaction (Figure 11). Whereas most High Plains artifacts are of lesser financial value, the large complete Paleoindian spear points remain highly desired in the artifact market. There are plenty of instances of river finds quickly moving between local finders to wealthy buyers located along the Front Range. This is a serious issue in that it generates competition for finding such objects and has turned artifact hunting into much more than a hobby or an avocational intellectual pursuit.

Figure 11. Slim Arrow site spear points found by the Andersen family between 1928 and 1930; they traded hands at least three times since the 1930s (note “sold” written on the image) and today reside in a private collection. (Drawings from the Andersen family archaeology catalog, courtesy of the University of Nebraska State Museum.)

The early history of eastern Colorado (1930s–1970s) saw extensive communication between artifact collectors and professional archaeologists. At that time, CRM was essentially nonexistent, and academic research was dominated by university professors and museum curators. There was a real need to learn about major sites from locals—sites to be tested given their high potential and integrity. Key collectors became nodes within such systems and were well known by everyone (professional and amateur) in the region. These included people such as the Andersen family in the Dust Bowl and others such as Forrest “Heavy” Felkner and L. M. Lytle who led E. B. Renaud to many sites in the early 1930s. Later, Al Parrish, Bert Mountain, and Tom Pomeroy (1950s–1980s) would continue this tradition, working with professional archaeologists from regional universities and museums, such as Joe Ben Wheat, Liz Morris, George Frison, Chuck Reher, and Dennis Stanford. Many of these interactions stemmed from conversations at the Loveland Stone Age Fair, a noncommercial artifact show that has been held nearly annually in northeastern Colorado since 1935 (Yeager Reference Yeager1990).

However, things began to change in the 1970s–1980s, with the professionalization of the discipline, the passage of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act for Federal lands (1979), and the formation of archaeological ethics codes that heavily discouraged interacting with artifact collectors, even if artifacts were legally found on private property. Artifact collectors began to be viewed by many professional archaeologists in a negative light—as individuals with no moral or ethical compass, who were gathering artifacts solely for their own needs or financial gain. Professional archaeologists had less need for “new” sites to be reported to them because they were routinely finding them on their own with CRM crews and generating data through this process.

The 1980s–2020s has seen limited interaction between artifact collectors and professional archaeologists, and it is usually related to those collectors or professionals wanting to meet somewhere in the middle (Kinnear Reference Kinnear2008; LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003). Much of this interaction relates to Paleoindian archaeology, given that these sites are rare and difficult to find. It takes a lot of eyes on the ground to find large Paleoindian sites (individual points are not so hard to find in CRM or academic archaeology). Therefore, professional archaeologists often take all the help they can get. Researchers such as Jack Hofman, Steve Holen, Bonnie Pitblado, and others have continued this tradition (Asher Reference Asher2016; Blackmar Reference Blackmar2001; Hofman Reference Hofman and Amick1999, Reference Hofman, Hurst and Hofman2010, Reference Hofman2016; Holen Reference Holen2001; Pitblado Reference Pitblado2003; Williams Reference Williams2015).

A real concern we have is what is happening to the old-time family collections from eastern Colorado. We are now several generations removed from the Dust Bowl, and few collections from that era are still held in family hands, with most split up and sold years ago. Thankfully, most of the Andersen collection was donated to the University of Nebraska State Museum in the early 1970s (Andersen Reference Andersen1988, Reference Andersen1990; LaBelle Reference LaBelle2005). Many collections from the Filthy Fifties are now subject to the same loss. For instance, the passing of the legendary collector Jerry Chubbuck (Reference Chubbuck1959; Wheat Reference Wheat1972) led to the auction of much of his collection. His “World's Wonder View Tower,” a tourist attraction in Genoa, Colorado (http://coloradopreservation.org/2017-list-colorados-most-endangered-places/wonder-tower/), once housed a room that had several walls covered in frame after frame of artifacts, many personally collected from the sandy country of Kit Carson County and beyond. Jerry even had a mammoth laid out on the floor of this artifact room, overwhelming visitors with the magnitude of his collecting from the 1950s to 1980s. Many of Chubbuck's Paleoindian frames were purchased and kept “intact” by collectors in the region (e.g., Muniz Reference Muniz, Huckell and David Kilby2014), but the more common Late Prehistoric and Archaic frames were not equally sought after and were sold in auction.

Where will these massive and often multigenerational family collections end up? Museum and universities would be logical and respectful places. But how do we convince families to donate to such places when there is monetary value for them to split the collection and individually auction the larger, rarer, and complete pieces? What if the collection has limited or poor provenience? Does it still have “value” to museums and academia? These conversations should be taking place within our discipline, and information should be salvaged from these collections as well as possible before it is too late to do so. This is an ethical imperative for professional archaeologists.

Finally, what does the future hold for younger generations? Can walking fields compete with video games and social media that connects people around the globe? Will artifact hunting continue to be seen as a hobby in the future, as a way to learn about the past in one's region, through salvaging artifacts from plowed fields and river bottoms? Or will this passion fade with time? How can archaeologists help shape the future of artifact collecting?

We consider artifacts, features, and sites as windows to the past, and they open conversations into our present day. Through their study, we can give thoughtful consideration about what they represent—and to whom they once belonged—and welcome Native American peoples into the broader discussion. Although it is not common in the region today with respect to private property, we can envision bringing Native American consultation (personnel from Tribal Historic Preservation Offices as well as interested individuals) to this region in the coming years. Perhaps this could be facilitated through local museums or through artifact shows such as the Loveland Stone Age Fair, where fruitful conversations might revolve around (1) the fact that Native peoples not only used to live in the region but are still here today, (2) challenges and creative ideas for preservation, and (3) building partnerships for sharing Native American histories in local museums, schools, and public places.

WHAT CAN PROFESSIONAL ARCHAEOLOGISTS LEARN BY WORKING WITH COLLECTORS?

We would like to end our “tailgate chat” by providing suggestions about what professional archaeologists can learn by working with artifact collectors. The very first thing we should do is to stop assuming that all artifact collectors are the same. There is a spectrum of behaviors and motivations—from farmers who make occasional surface finds, to those who see artifacts as commodities, to die-hard collectors with little archaeological knowledge (or desire to acquire it) who still hold a passion for finding “objects,” and finally, to learned avocational archaeologists who see the historical, intellectual, and cultural value of the objects they have found (Kinnear Reference Kinnear2008; LaBelle Reference LaBelle, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003). We think that working with this last community benefits the study of the archaeological record the most, because the motivations, interests, and ethics align best with the professional archaeological community.

We feel there is great value in working with artifact collectors, especially those who see the value of artifacts as important pieces of local history. We emphasize that we are speaking about artifacts from private property, where permission was obtained for surface collection of artifacts from disturbed contexts such as blown fields. We also explicitly condemn illicit artifact collection from public lands and the disturbance of human remains or funerary objects from private or public lands. Thankfully, Colorado has a specific process (under state statute) for reporting and managing such inadvertent discoveries of unmarked graves.

There is great utility in keeping simple ledger records linking artifacts with specific locations logged with GPS or other mapping technology (USGS) maps. One of the most frustrating aspects of dealing with artifact collectors is the loss (or lack) of spatial information associated with individual artifacts. We think that professional archaeologists and museum personnel—rather than just hoping that artifact collectors will stop what they are doing altogether—should offer basic workshops and web-based videos on artifact GPS logging, basic documentation, and artifact labeling. At least this type of training (though perhaps controversial or unconventional to some professional archaeologists) would address the issue of missing spatial data.

We want collectors to continue to provide professional archaeologists leads on important sites. But this requires communication from the professional community (academic researchers such as university professors or museum curators) as to which types of sites should be reported—not all sites are equally important or valuable for research, management, and education purposes. We feel that it would be useful to focus on sites containing rare items. For eastern Colorado, this would include sites with five or more Paleoindian points of any single type, marine and freshwater shell artifacts, atlatl weights, steatite vessel fragments, artifact caches, rare forms of pottery, glass beads, and other contact-era items that Colorado State University (CSU) archaeologists have researched over the past 15 years (e.g., Calhoun Reference Calhoun2011; LaBelle Reference LaBelle2015; Packard Reference Packard2015; von Wedell Reference von Wedell2011). Collectors find so many sites and tools that it is impractical for professional archaeologists or students to record every known site.

As part of this shared research effort, it would be helpful for collectors to fill out short, one-page site forms (more like site leads) on their sites for the SHPO so that this information can be shared with interested archaeologists—either academic or CRM—doing surveys within the area. As mentioned earlier, such site forms were submitted as part of this project to record minimal information on these sites for the Colorado and Nebraska SHPOs (Matsuda Reference Matsuda2021). Consulting with local collectors should be seen as a valuable part of Class I research for CRM projects and should be encouraged by agencies when legally appropriate.

We also need archaeologists to appreciate the scale at which artifact collecting has occurred over the past century in eastern Colorado alone, which has led to the removal of hundreds of thousands of tools from site surfaces (Shott Reference Shott2017). The small number of tools found on most CRM or academic surveys is likely not representative of what the site would have looked like years earlier. Instead of ignoring the reason behind many of these limited find surveys, professional archaeologists need to do a better job of measuring and addressing this significant cultural modification of the archaeological record.

Large archaeological sites (perhaps better termed “archaeological landscapes”) from blown fields or sand sheets are unlike most sites that archaeologists find during CRM survey. Collectors tend to search these sites at advantageous times, after strong spring winds and before the crops have grown—which is equivalent to a post-fire inventory. It gives a completely different read of the landform than a traditional archaeological survey does. The degree of use and reuse of the landform is readily evident with such high-visibility windows. Our playa case study certainly demonstrates the sheer size and diversity of these landscapes, with the cumulative artifact inventories clearly overshadowing anything that would be found during a one-day survey of the property. What professional archaeologist has the time or resources to, at the drop of a hat, dedicate the many hours involved in monitoring such large sites? There are dedicated avocational archaeologists out there, such as Mike, who stated, “Every time my back ached after a dawn to dusk ‘hunt,’ I told myself, ‘but it's for the science.’” He might have been joking or perhaps a bit sarcastic when he told us that story. But honestly, that level of effort must be recognized, utilized, and rewarded rather than written off as just the work of another troublesome collector who should be avoided.

Finally, we hope that in coming years, we can all scoot together and make room on our pickup's tailgate and welcome Native American partners. There is so much to be gained by sharing this story—not only with the people who live there today but with those whose ancestors lived there for millennia. Imagine what we could learn with more communication, mutual respect, and recognition. These objects have great importance to more than just the archaeologists and the collectors. Together, we can create a future that benefits everyone interested in the history of this little corner of the Great Plains.

Acknowledgments

This article was the result of many conversations—not only between the authors but with the many archaeologists and collectors we have met over the years and along the way. We would like to specifically thank Chris Johnston, Kelton Meyer, and John Seebach for their feedback on earlier versions of the article, and our anonymous reviewers for their thoughts and ideas on clarifying and improving it. Thanks to Alan Osborn and staff of the University of Nebraska State Museum, to the Playa Lakes Joint Venture, and to photographer Brian Slobe for their permission to reproduce several images in this article. The James and Audrey Benedict Fund for Mountain Archaeology provided funding for this project. Marie Matsuda received scholarships from the Loveland Archaeological Society and Northern Colorado Chapter of the Colorado Archaeological Society for her thesis research.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented the playa case study are accessible in Marie Matsuda's thesis project (Matsuda Reference Matsuda2021).

Competing Interests

The author(s) declare none.