Research on informal carers dates back to the 1950s, at which time the bed numbers in asylums in the UK and USA first began to decline. There was thus a new requirement in the UK for informal carers (usually relatives) to be involved in the day-to-day care of people with serious mental health problems. The first empirical research linking family atmosphere and the outcome of psychosis was initiated soon afterwards, Reference Brown, Birley and Wing2 and the first attempts to modify outcome by family intervention followed. Reference Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, Eberlein-Vries and Sturgeon3,Reference Falloon, Boyd, McGill, Razani, Moss and Gilderman4 The early interventions were based on general principles, and lacked a detailed understanding of the particular psychological disturbances associated with caring roles in psychosis. We now know considerably more about the relationships between people with psychosis and their carers. Reference Askey, Holmshaw, Gamble and Gray5 Carers' appraisals of their situation and of the resources they have to cope with it are more crucial to both carer and service user outcomes than the apparent severity or scope of the problems faced. Reference Scazufca and Kuipers6 Although all carers face potential stresses, their appraisal of the situation and how they try to deal with it contribute to the well-being of service users and should be key targets for intervention. It seems timely to integrate this new information and relate it to interventions that target improvement in carer well-being as a primary focus. Although such a model may also apply to other disorders, the evidence presented here concerns those caring for people with psychosis.

Definition

Carers of people with psychosis are usually family members, mainly parents or partners. Reference Lauber, Eichenberger, Luginbuhl, Keller and Rossler7 There is an ongoing issue about how carers define themselves (e.g. ‘carer’, ‘parent’ or ‘supporter’), but this does not affect the undoubted strains of the role. In our view, caring for people with psychiatric problems is not generally a matter of choice. Reference Kuipers and Thornicroft8 It is often impossible to walk away, although carers vary in their degree of acceptance of the role. We have identified that it is ‘an inherently unequal role; the person doing the caring has more responsibility, and has more to do than the person being cared for, who is to some extent dependent’ (Kuipers & Bebbington: p. 217). Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Sartorius, Leff and Lopez9 There are other definitions. The mental health charity Mind (www.mind.org.uk/help/people_groups_and_communities/how_to_access_services-information_for_carers#whois) states that ‘you are a carer if you provide help and support to someone with a mental health problem and/or a physical disability.’ They go on to distinguish between friends and family who provide unpaid care and paid professionals, and underline that the caring relationship can be mutual. The website of the Princess Royal Trust for Carers (not restricted to mental health carers) defines a carer as ‘someone who, without payment, provides help and support to a partner, child, relative, friend or neighbour, who could not manage without their help’ (www.carers.org).

Impact of care

Caring for a family member with psychosis is demanding, often prolonged, and associated with increased levels of stress and distress. Reference Scazufca and Kuipers6,Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Sartorius, Leff and Lopez9–Reference Roick, Heider, Bebbington, Angermeyer, Azorin and Brugha11 Recent evidence suggests that as many as a third of carers meet criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. Reference Barton and Jackson12 Carers also experience a great sense of loss, comparable to levels recorded in physical bereavement. Reference Patterson, Birchwood and Cochrane13 The first carer study evaluated the impact on the wives of men discharged from psychiatric hospital. Reference Yarrow, Schwartz, Murphy and Deasy14 This was the start of research into the so-called ‘burden’ of such care. As can be seen from the use of this terminology, caring was felt to be a solely negative experience, and the early researchers did not ask about positive effects. In these early stages burden was defined as ‘the difficulties felt by the family of a psychiatric patient’ (Pai & Kapur: p. 334) Reference Pai and Kapur15 or more broadly as ‘the effect of the patient upon the family’ (Goldberg & Huxley: p. 127). Reference Goldberg and Huxley16

Expressed emotion

Pioneering research made it clear that, although family involvement could be helpful, some reactions – particularly if critical or overinvolved – were associated with subsequent relapse of the service user. Reference Rutter and Brown17 We have shown, in an analysis of prospective studies, that high levels of this expressed emotion (EE) are a reliable predictor of patient outcomes in schizophrenia: overall, the relapse rate for those returning to families with low EE was 21% compared with a 50% relapse rate in families with high EE. Reference Bebbington and Kuipers18 Further studies confirmed that ‘burden’, particularly as assessed by the carers themselves, was strongly correlated with high EE. It was also related to poor carer outcomes such as stress, distress and low self-esteem, and to less effective, avoidant coping, even at first episode. Reference Raune, Kuipers and Bebbington19,Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler, Freeman and Watson20

Attributions

Another strand of research originated from Weiner's theory of attribution, emotion and behaviour: whether events were good or bad, and why they happened. Reference Weiner21 An attributional model of EE, including the concepts of intention and control, was first put forward by Hooley. Reference Hooley22 Since then it has become clear that high-criticism carers are more likely to make ‘controllable’ and ‘personal’ attributions, both in psychosis and in other disorders such as diabetes. Reference Barrowclough and Hooley23,Reference Wearden, Ward, Barrowclough, Tarrier and Davies24 In other words, if carers are critical, their attributions are more likely to lead to assertions that patients are substantially in control of – and therefore to blame for – negative events. This in turn relates to greater carer distress and negative evaluations of the caring role. Carers’ appraisals of and reactions to their role not only affect their own well-being, but also may improve or impede recovery in those they care for. Reference Bebbington and Kuipers18 More recent evidence suggests a mechanism for this: service users are able to perceive criticism from their carers accurately, Reference Bachmann, Bottmer, Jacob and Schroder25–Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Freeman and Fowler27 and perceptions of carer criticism have in turn been linked to poorer service user functioning. Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Freeman and Fowler27

Illness perceptions

Other methods of evaluating the caring role have developed from Leventhal et al's conception of illness perceptions. Reference Leventhal, Nerenz, Steele, Baum, Taylor and Singer28 As in physical ill health, Reference Hagger and Orbell29 carer illness perceptions and the consequent behavioural decisions are more likely to predict carer outcomes than illness severity. This has been shown to be equally relevant for informal caring in psychosis; Reference Lobban, Barrowclough and Jones30,Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler and Freeman31 if carers feel that they are not in control of their relative's illness and that it will last a long time, they experience more stress and depression and have more negative views of the impact of care. Moreover, if carers and service users disagree about these illness perceptions, carers tend to have lower mood and self-esteem. Reference Kuipers, Watson, Onwumere, Bebbington, Dunn and Weinman32 Such disagreements tend to be observed more in high-EE relationships. Reference Lobban, Barrowclough and Jones33

Positive caregiving experiences

In the past decade, as part of an attempt to explore caregiving within a broader framework, attention has been given to the positive aspects of the caregiving relationship and their links with carer and service user outcomes. Reference O'Brien, Gordon, Bearden, Lopez, Kopelowicz and Cannon34,Reference Grice, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler and Freeman35 Thus, we know that many carers report positive caregiving experiences, including feelings of satisfaction and improved self-esteem. Reference Veltman, Cameron and Stewart36,Reference Chen and Greenberg37 Further, carer warmth can serve as a protective factor against relapse, Reference Brown, Birley and Wing2,Reference Bertrando, Beltz, Bressi, Clerici, Farma and Invernizzi38,Reference Ivanovic, Vuletic and Bebbington39 particularly in some Black and minority ethnic groups. Reference Lopez, Hipke, Polo, Jenkins, Karno and Vaughn40,Reference Breitborde, Lopez, Wickens, Jenkins and Karno41

Coping

There is now some literature on the coping responses optimal for carers of people with psychosis. Reference Birchwood and Cochrane42–Reference Barrowclough and Parle44 This is based on the ideas of Lazarus & Folkman that coping itself depends on accurate appraisal of situations, on one's resources and on how these are marshalled. Reference Lazarus and Folkman45 In psychosis, avoidant coping (a style of emotional response characterised by ‘hoping problems will go away’) may be useful for problems that resolve naturally, but not with more enduring or worsening problems. Active and proactive strategies seem better at reducing the impact on levels of carer burden, even in the early stages of illness. Reference Raune, Kuipers and Bebbington19,Reference Scazufca and Kuipers43,Reference Magliano, Fadden, Economou, Held, Xavier and Guarneri46 These sorts of strategies are usually shaped and encouraged as part of family interventions. Reference Barrowclough and Tarrier47,Reference Leff, Kuipers and Lam48

Social support

The stigma and shame associated with mental ill health can lead to a significant reduction in social networks, even for carers. Reference Magliano, Fiorillo, De Rosa, Malangone and Maj49,Reference Gutiérrez-Maldonado, Caqueo-Urízar and Kavanagh50 The importance of social support in reducing distress and encouraging more proactive coping in carers has been confirmed. Reference Joyce, Leese, Kuipers, Szmukler, Harris and Staples51,Reference Magliano, Fiorillo, Malangone, Marasco, Guarneri and Maj52

Intervention studies

Carer outcomes have been primary objectives in few intervention studies. The research impetus in relation to caregiving in psychosis has so far been towards improving service user outcomes. This has had some success. Family intervention in psychosis, involving the whole family in negotiated problem-solving, reappraisal and reattribution of difficulties, and emotional processing of the loss and grief, has shown some improvements in carer ‘burden’. Reference Cuijpers53 However, most improvement has been in reducing service user relapses. 54,Reference Pharoah, Mari, Rathbone and Wong55 In the small number of studies focusing on carer outcomes, Reference Barrowclough, Tarrier, Lewis, Sellwood, Mainwaring and Quinn56,Reference Szmukler, Kuipers, Joyce, Harris, Leese and Maphosa57 only two have demonstrated a positive impact on carer well-being. Reference Berglund, Vahlne and Edman58,Reference Giron, Fernandez-Yanez, Mana-Alvarenga, Molina-Habas, Nolasco and Gomez-Beneyto59 However, this is not surprising, as there is evidence that carer well-being relates closely to service user outcome. Reference Askey, Holmshaw, Gamble and Gray5

Cognitive model of caregiving

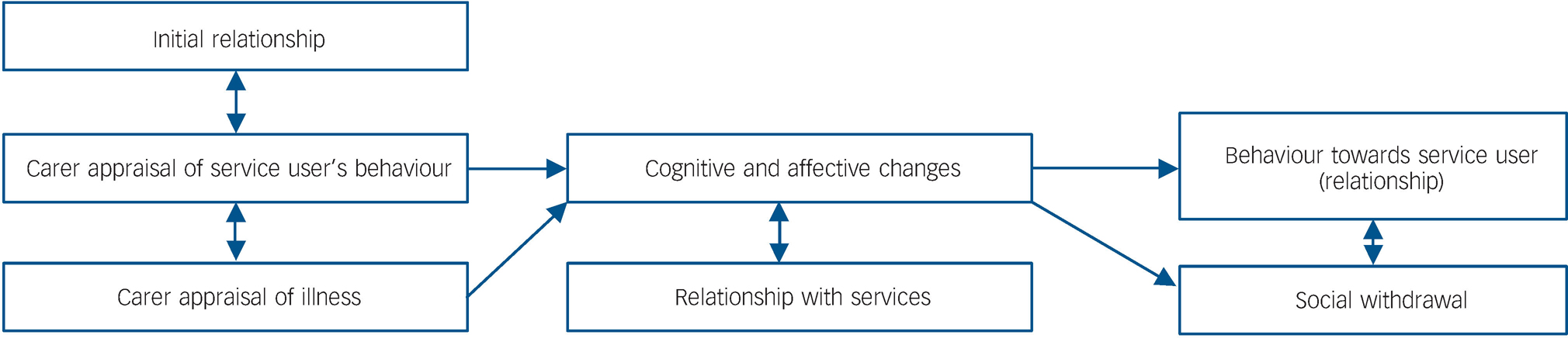

On the basis of a growing and complex literature, we propose that caregiving appraisals and reactions in psychosis can be usefully described in a model as shown in Fig. 1. It is these appraisals that engender carer cognitive and affective reactions, and lead to a range of carer behaviours towards service users and towards services, and to different carer outcomes. The pathways and their interactions constitute testable hypotheses, and suggest that specific interventions targeting these appraisals and their maintenance factors might improve outcomes. Most existing research is of analyses restricted to a single domain. Our model integrates this prior research for two linked purposes: to set up testable hypotheses of interactions, and to develop interventions, the evaluation of which will then form collateral tests of the original model. The research to test these hypotheses has yet to be done. It is hoped that both the model and the interventions that might arise from it will be developed further.

Fig. 1 Cognitive model of carer responses in psychosis.

Given the overall model, we suggest further that three different styles or types are at present supported by the evidence, interpreted in the light of clinical experience of intervention with families dealing with psychosis. Although our typology of the characteristics of caregiving can never be exact, it is based in empirical research, and we think it will be of use in shaping interventions to the needs of caregivers. Analysis in terms of the three styles will, we propose, maximise the likelihood of change and of change being sustained. They provide testable hypotheses to evaluate both the maintenance effects and the interventions themselves.

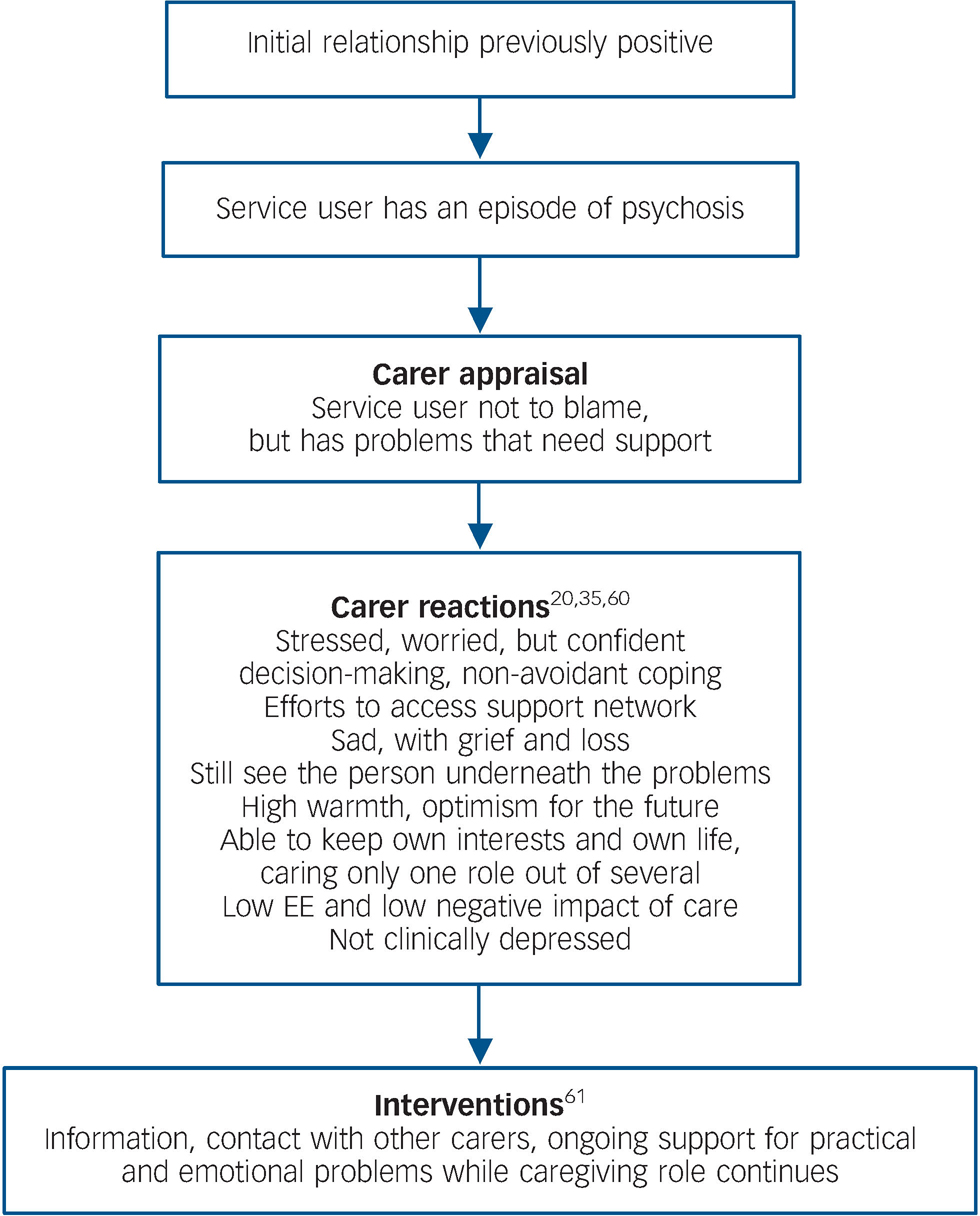

Positive relationships

The first type of caregiving is represented by those who, for whatever reason, previously had a positive relationship with the person developing psychosis (Fig. 2). Before the illness, relations were warm and communicative, and interactions were positive. The carer thus sees the service user as a person, not just as a compendium of problems. The problems that do emerge are then more likely to be understood as unusual, not as part of normal ‘adolescent’ bad behaviour, and therefore as something requiring a different reaction. The service user is seen as needing care and help, while respect for their autonomy is nonetheless maintained. Because problems are recognised, even if the cause is not yet identified, these carers are able to ask for help, both from formal sources and from their social network, in a manner that is likely to be effective and sustainable. They thus do not become isolated. Moreover, when they are offered help, they are more likely to accept it and to act upon it. They are able to make decisions confidently. Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Freeman and Fowler60 Their key appraisals are positive: that the care recipient is not to blame but needs help for their problems, Reference Grice, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler and Freeman35 and that these might be soluble if carer and recipient work together.

Fig. 2 Positive relationships. EE, expressed emotion.

Such carers still require intervention. Reference Lawrence, Murray, Samsi and Banerjee61 At the very least they need information, support, respite and help in integrating a caring role into other roles in their lives. They are more likely to continue with their other roles such as work and childcare, not abandoning them to care only for the service user. Although these carers may be stressed and sad, they are rarely clinically depressed. They respond positively to offers of help from services, and they may themselves be particularly helpful to other carers. However, there is a danger that services may ignore this group of carers, feeling that they are coping well, and thus fail to be responsive or proactive.

Emotionally overinvolved relationships

Emotional overinvolvement in those caring for people with psychosis is a strong marker of poor current psychological and physical health. The evidence suggests that it may also be an indicator of poor future health. Reference Breitborde, Lopez, Chang, Kopelowicz and Zarate62 Emotional overinvolvement has strong positive links with feelings of loss, Reference Patterson, Birchwood and Cochrane13 self-blame and guilt about being responsible for the person's illness. Reference Leff and Vaughn63–Reference Peterson and Docherty65 Carers with this style are more likely to be parents, as this is a parenting style perfectly appropriate for younger children. Relationships have typically been good but seem rooted in the past. Such carers will talk about how ‘wonderful’ or ‘beautiful’ the person used to be when a small child. The loss and transformation of this child into, first, a difficult adolescent, and then into someone with mental health problems, is accompanied by understandable grief and distress. The appraisal at this stage is that the person is not to blame, but needs to be buffered against all difficulties. Reference Grice, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler and Freeman35 This becomes the carer's life work. It is often taken up at the cost of other roles, including employment.

We propose that interventions need to focus on finding positives about service users as they are now, not just as they were in the past. Such carers also need permission to take back their own lives, to address issues related to their own health and well-being, and to have perspectives beyond those related to the caring role. Because caring for people with mental health problems can be both isolating and stigmatising, these people are likely to have lost their own support network. Thus it can be useful to help them re-engage with confidantes and social support, either through other carers, or informally.

Such carers are often those who continue to search for a cure. This would bring back the potential of the ‘lost child’. Anything less than this can feel as if they are giving up, or not caring enough. Offering information and advice to these carers may be unproductive, as the mere provision of facts will not help. Instead, it is necessary to foster a caring style that assists the care recipient to become more independent, thereby reducing the buffering role of the carer, while encouraging carers to re-engage with their own plans and interests. A problem-solving approach may reveal that the person with psychosis is still capable of adult roles. It can then be used as the basis for gradually giving these roles back to the person. This can parallel encouragement for carers to find other roles for themselves. Offers of respite and breaks can be particularly helpful to reduce stress and to allow other interests to develop (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Overinvolved relationships. EOI, emotional overinvolvement.

Critical and hostile relationships

Critical and hostile attitudes are the more common negative reactions to the stresses of the caring role in psychosis, and can be found in all types of carer, whether parents, partners, children or siblings. Earlier relationships between service users and carers will often have been poor, with the service user perhaps displaying a long history of adolescent turmoil and poor performance at school. Substance misuse on the part of the service user is also likely, whether of alcohol, cannabis, other street drugs or all of these. Although problems will be noticed, they will tend to be seen as normal but difficult behaviour patterns, not as signs of mental ill health. In this relationship style a longer duration of untreated psychosis is likely, associated with poor role performance. Because of the poor relationship, the service user is less likely to confide in the carer, and more likely to deny problems or to refuse to discuss them. The initial presentation may therefore be delayed, with more severe symptoms and a more dramatic entry to services. Carers at this stage can be devastated by the involvement of mental health services, with all the associated stigma and shame. Carer appraisals are then likely to involve blaming the service user's character or behaviour, particularly if the latter involves drug use. Carers themselves will not feel to blame, or that they can do much that will make a difference. The onus will usually be on the service user to ‘get better’, by taking medication and other treatment, and by taking some responsibility for their progress. This is when criticism and hostility develop. In this relationship type, carers themselves are likely to be angry, upset, anxious and depressed. They may have low self-esteem, and feel that nothing they can do will make any difference. They will exert pressure on services to be helpful, and on the service user to improve by their own efforts. Such carers will often try to cope by using emotional strategies such as avoidance – waiting for things to get better by themselves.

Interventions for critical carers may not always be possible. The more rejecting carers may not take on the caring role at all, may abandon it during the initial phase of illness, or may not engage productively with services. For those who remain, the provision of information can be crucial. These are the carers who may respond best to information and advice. Even so, the information will probably need to be given more than once, over quite long periods, as it will be new and often unwelcome. Unwelcome information and disconfirmation is never processed and acted on as easily as confirmatory information. Sharing information with a group of carers, answering questions and discussing answers, is often better and more easily understood than information given in a didactic format.

An important part of intervention for this group of carers is the reattribution of control and consequences, by suggesting to them that service users are not totally in control of their thinking and behaviour, as it is now strongly influenced by symptoms of psychosis. Reference Watson, Garety, Weinman, Dunn, Bebbington and Fowler66 It is a useful strategy to discuss directly with carers and service users the impact of such symptoms as voices, and how carers can help in dealing with them. Negotiated problem-solving is another key focus, with both parties encouraged to change a small part of their behaviour as a way of finding out whether this can improve things.

Negative communication patterns may be particularly unhelpful as they are associated with negative affect in patients. Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler, Freeman and Watson20,Reference Barrowclough, Tarrier, Humphreys, Ward, Gregg and Andrews67 Carers may be unaware of this. Demonstrating and then modifying the impact of such communications can be another useful goal of family therapy sessions. Finally, an appreciable proportion (around a third) of carers in these critical relationships have clinical levels of depression. This is associated with more avoidant coping, low self-esteem and an understandable pessimism. Reference Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler, Freeman and Watson20 We recommend working directly on this either in family sessions or individually with carers. This should include a focus on negative cognitions as well as on behavioural activation and activity scheduling (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Critical and hostile relationships. DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

Discussion

Consistent with an increasing trend to categorise subgroups of carers, Reference Lawrence, Murray, Samsi and Banerjee61,Reference Stengard68 we have developed a testable model that could be used in future research: for instance, to test the maintaining factor of avoidant coping and resultant carer distress. We have also provided a typology of relationships between people with psychosis and their informal carers. In some families there will have been difficult problems including previous neglect and abuse. Reference Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha, Singleton, Farrell and Jenkins69 These kinds of families will not usually be in caring roles, by definition. In families providing care, not all carers will fit these types of caregiving. Families have widely varying structures, relationships and histories. In some families, for instance, carers will have opposing views; parents can show contrary reactions, and find themselves arguing with each other as well as with the service user. Over time, initial reactions of shock, bewilderment and denial of mental health difficulties can settle into adaptive and productive relationships that underwrite good recovery. For other families, things do not improve: there are further episodes, and problems continue or indeed multiply. The stress of the caregiving role can then take its toll in depression, anxiety, exhaustion, exasperation with the service user and frustration with inadequate services. The result may be that no one in the family is managing, and all that its members share is pessimism and cynicism. Families may also become ‘stuck’ at these initial stages, finding it impossible to adapt to the current reality or to new problems, because this feels like a defeat, giving up. More problems then occur, confirming that the only solution is the struggle to get better treatment.

However, more recently positive aspects of caregiving have been identified. Reference Veltman, Cameron and Stewart36,Reference Chen and Greenberg37 When asked, long-standing carers may be more optimistic than those caring for people at an early stage of their illness. Reference Onwumere, Kuipers, Bebbington, Dunn, Fowler and Freeman31 Families who pass through the initial shock and stigma may find a way of seeing caregiving as enriching. Recent studies have reported that recovery after an initial episode is more rapid in those with positive relationships and family support. Reference McFarlane and Cook1,Reference O'Brien, Gordon, Bearden, Lopez, Kopelowicz and Cannon34 Our own intervention study showed that service users with carers demonstrated better outcomes from cognitive–behavioural therapy or family intervention. Reference Garety, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Dunn and Kuipers70 These findings are a welcome change from the more negative views of caregiving, and are consistent with a growing body of research suggesting service users obtain better outcomes when they have carers. However, it is not yet clear exactly how carers exert positive influences, nor whether these effects also relate to carer outcomes. Both topics require investigation, but there are indications that good problem-solving skills in patients and carers may have a role. Reference O'Brien, Zinberg, Ho, Rudd, Kopelowicz and Daley71

Improving carer outcomes requires a theoretical and practical understanding of the mechanisms that develop and maintain carer distress, together with those that optimise the positive aspects of the role. Although carers remain a resource of the greatest importance in the effective management of psychosis, Reference Kuipers and Bebbington72 they very much merit the attention of clinicians in their own right.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.