Early on the morning of Tuesday, 26 May 1868, the eminent Victorian journalist George Augustus Sala arrived outside Newgate Prison to report on the last “public” execution in Britain. This was not his first such assignment. Sixteen years earlier, he had attended the hanging at Lewes (Sussex) of Sarah Ann French for poisoning her husband.Footnote 1 This time, the condemned was Michael Barrett, the only man condemned for “the Clerkenwell Outrage,” when he and several other Fenians had dynamited the wall of Clerkenwell Prison in an attempt to free their associates confined within, killing twelve people and injuring more than 100 others.Footnote 2 If murder could ever be said to warrant the deliberate killing of the perpetrator by the state, execution might well have seemed particularly appropriate for this crime.

Sala’s account was not much concerned with the crime, however. It focused instead upon whether the effects of Barrett’s execution upon those in attendance justified the suffering inflicted upon him. For over a century, this calculation – memorably defined by the novelist and London magistrate Henry Fielding in 1751 – had been a central element of official thinking about executions. Both their moral acceptability and their deterrent efficacy depended upon their being staged in such a manner as to ensure that the public’s detestation of the crime being punished outweighed its natural abhorrence of any apparent agonies endured by the condemned. To what extent did Barrett’s execution measure up to this standard?

In Sala’s view, not very well. After French’s execution in 1852, he had taken the train to Brighton in company with many of his fellow attendees. “Every minute particle of the horrible ceremony was enumerated, discussed, commented upon,” he noted then, “but, I can conscientiously declare that I did not hear one word, one sentiment expressed, which could lead me to believe that any single object for which this fair had been professedly made public, had been accomplished.”Footnote 3 Sixteen years later, Sala was pleasantly surprised to observe that the usual “scum of the abandoned class” comprised “only the smaller part of the throng” gathered to witness Barrett’s hanging. He perceived the crowd to consist, in “very large proportion,” of “respectable working men, or small tradesmen” who, “knowing that executions are henceforth to be conducted privately, had come chiefly to avail themselves of the last chance” to see one.Footnote 4 As the fatal hour (8.00 a.m.) drew closer, “the crowd became denser, but never dangerously, and seldom inconveniently so; and … the influx was chiefly due to the arrivals of workpeople, male and female, who had secured an extra hour for their breakfast in order to take the execution on their way.” Nor did Sala detect either a dangerous sympathy for the condemned or detestation of the hangman. The shouts of “Hats off,” “Bravo,” and of the condemned man’s name seemed “more … outbursts of impulsive feeling,” signifying “little more than recognition,” and “such as they were, they were soon hushed.” In general, Sala perceived this last conventional execution crowd to be remarkably well-behaved: to be substantially and reassuringly composed of that better class of working people which all high-minded Victorian commentators hoped to see emerging by the late nineteenth century.

But Sala also saw no evidence that the crowd derived any great moral message from the display. After the platform fell from beneath Barrett’s feet – with that “sound, once heard never to be forgotten” – his “powerful frame trembled, and [his] knees shook convulsively,” actions that persisted “even after the ‘swinging’ had been stopped” by the hangman. “A general outcry of horror from men and boys, and a few piercing shrieks from some women, were fitting accompaniments to the scene.” Sala also noted that journalists had been prevented from having any interactions with Barrett before he was brought out onto the platform. In yet another departure from long established practice, he had even been pinioned beforehand. All this had surely been done with the intention of shortening, as much as possible, the public display during this last of public executions.

If the attending crowd derived no moral lesson from the open display of executions, and if the condemned could not be reliably assured of a mercifully swift death, then surely the removal of executions behind prison walls – authorized by a law passed three days after Barrett was hanged – would resolve both problems. Three months later, Sala was on hand to test this proposition.

This time the condemned, hanged inside Maidstone Gaol, was Thomas Wells, a nineteen-year-old railway porter who had impulsively shot and killed a station master “after being mildly reprimanded” by him.Footnote 5 Somewhat contradicting his observations on the previous occasion, Sala noted that, “For the first time in England the law has taken its course without the shameful accessories of a howling, screaming, struggling, blaspheming mob,” save for “forty to fifty of the dregs of the population – consisting principally of lads of from six to fifteen – squatting on the pavement” near the gaol in the hope of seeing something. The “veriest scum which even a garrison town is capable of throwing to the surface,” they were nevertheless “the mere ghost of an execution-mob.” Wells was hanged at 10.30 a.m. half an hour after the two dozen people summoned within the gaol “to witness his supreme agony” – “half of them officers connected with the gaol, and half the representatives of the public” – had been admitted. On the scaffold, while he was being pinioned, Wells sang a hymn “in a low and tremulous chant,” continuing to do so even after the cotton cap was pulled over his head.

The dropping of the platform was no more effective in instantly killing Wells than Barrett. This time, however, the horrible realities of execution were experienced by the few attendees – and by Sala’s readers – far more vividly than ever before.

Before life was extinct, … all present were invited to advance up to the hanging body. Some convulsive struggles of the strapped legs, throat gurglings, which were heard distinctly through the cap, a deep clenching of the clasped rapidly hands, which turned blue, and a discolouration of the neck, under the ear where the halter came – such were the signs noted silently by those whose painful duty it was to look on.

By comparison with previous executions, Sala thought this one to be “commendably decorous, orderly, and brief.” Even so, “the spectacle,” however diminished in scale and concealed from the crowd, was “probably more harrowing than any other scene of the kind.”

Overview

Few subjects so vividly confront us with the gulf between “then” and “now” as public execution; and few moments seem so clearly to signal a transition from “pre-modern” to “modern” as that when executions ceased to be conducted in the immediate public gaze. As we will see near the end of this book (and as Sala’s continued use of the word “spectacle” might imply), the change that took place in England in 1868 was not so much from public to non-public executions, but rather to executions that were made “public” in a different manner. Officials had previously sought to contain objections to the visible work of the gallows in several ways: by seeking to make the death inflicted instantaneous; by limiting the number of people hanged at any one time and place; by seeking to ensure that the crimes for which executions were inflicted deserved to be so punished; and by staging executions so as to keep the public mind fixed more firmly upon the offence than upon the suffering offender. In making these calculations, officials had relied upon a cooperative media – especially the newspaper press – since the early eighteenth century at least. For several decades after 1868, indeed, they expected the press to keep the public’s eye focused upon the just punishment of the crime, as well as to alleviate any fear that the outward concealment of executions might potentially mask either inequities of treatment or cruelties in their conduct. When at last execution itself, even for murder, came to seem an unacceptable cruelty, it was abolished.

This book provides the first comprehensive, single-volume account of how and why the character, the physical location and the numerical scale of English executions changed during the two-and-a-half centuries following the Restoration. Chapter 2 shows how spectacular modes of execution, which in England were already confined solely to traitors, were soon limited, in the duration both of the agonies inflicted and of the subsequent display of bodily parts, decades before continental states stopped decapitating common criminals or breaking them on the wheel. Chapter 3 reminds us, however, that the quality of English mercy was strained in other respects. England executed far more common criminals than any other nation, a practice that was sustained, in part, by a religious doctrine that offered the hope of salvation in the afterlife, even for the worst criminals, while maintaining that there was relatively little difference between the condemned and all other “sinners.” By the last third of the eighteenth century, that belief system had been substantially eroded by mutually reinforcing changes in religious and emotional cultures. Chapter 4 shows how these new outlooks not only presented capital criminals as distinctly “other” to the law-abiding, but also viewed people who attended executions as a breed apart. Such views, animated by new beliefs and concerns that were particularly associated with a rapidly expanding urban environment, inspired both an extraordinary increase in the numerical scale of English executions by the 1780s and the concurrent effort to make executions more effective by reconceptualizing their dramaturgy.

No criminals seemed more definitively “other” than murderers. The desire to punish them more severely, while serving other compelling interests, inspired the single most striking innovation in English execution practice of the eighteenth century. The Murder Act of 1752 required that the dead bodies of executed killers be either anatomized and dissected (Chapter 5) or hung in chains upon a gibbet (Chapter 6). The purposes and effects of this remarkable statute are considered here at some length because, in recent years, many if not most historians have come to view both as being newly and distinctly regressive. In fact, as we will see, for most of the remainder of the eighteenth century, the practical effects of the Murder Act were at worst largely benign and, in some ways, positively beneficial to the interests of humanity. If post-mortem dissection ran the risk, as so many people feared it might, of inflicting unspeakable agonies upon a body that might still be able to experience them, the Murder Act at least confined those agonies to the one class of offenders whom everyone might think most deserving of them. In so doing, it conformed to an increasingly powerful new culture of feeling (or sympathy) which demanded not only that no more pain should be inflicted upon the bodies of those condemned for crimes other than murder than was strictly necessary to securing a deterrent display, but also a more substantial apprehension of the suffering of the victims of crime. By the mid 1780s, however, and increasingly thereafter, the unintended consequences of the Murder Act – first an accelerating epidemic of grave robbery to supply surgeons with anatomical “subjects,” then finally the resort of some men to serial murder to do so – definitively undermined the statute’s logic.

England’s traditional (landed) rulers had resolved the penal crisis of the 1780s by sharply reducing the scale of executions in any one jurisdiction. By this means, they hoped to preserve the letter of a “Bloody Code,” which assigned the death penalty to more than 200 separately defined crimes, at a time when most other western nations were entirely abandoning execution for all but a handful of the most serious offences. To the urban and middling (“urbane”) peoples of England, a criminal law that went substantially unenforced defeated the principle of certainty and proportion in punishments. Chapter 7 outlines the first phase of the struggle in parliament between these two perspectives, arguing that the reformers and their cause were more powerful than previous accounts, focusing upon the movement’s few formal successes, have allowed. Chapter 8 shows how the work of Home Secretary Robert Peel during the 1820s clearly responded to the power of this reform movement and prepared the ground for the decisive reduction of the “Bloody Code” in the mid 1830s. Chapter 9 completes the story by showing how the public culture of Victorian England, now governed by the priorities of urbane people, was surprisingly slow to abandon the last vestiges of the “Bloody Code” and never seriously questioned that moral equation between murder and execution which prevailed until the 1960s.

This study incorporates many of the insights of – but also seeks to move beyond – two major analytical perspectives that have dominated penal history during the last three decades. The first is a pronounced deference to theoretical perspectives, often at the cost of the historian’s close attention to detail. Michel Foucault doubts the degree to which “Enlightenment” influences upon the transition from public/physical punishments to psychological inflictions imposed behind prison walls were genuinely humane. His perspective has been viewed critically, but not unsympathetically, by Randall McGowen and others.Footnote 6 Pieter Spierenburg embraced Norbert Elias’s “civilizing process” as a means of explaining penal change as part of a long-term transformation in state power and social–cultural practices. His lead has been followed, with qualifications, by such prominent historians of England as James Sharpe.Footnote 7 The most eminent theorist of punishment, David Garland, while pointedly refusing to adhere to any one perspective, nonetheless embraces the theoretical enterprise itself.Footnote 8 The capacity of such work to stimulate significant and helpful reflections upon major developments in any one national context has recently been demonstrated by Peter King.Footnote 9

The strength of theoretical approaches is their insistence that we notice broad similarities in basic patterns of development throughout the western world. Those similarities, however, while persuasive at a macro-level of analysis – where the landscape is viewed, as it were, from high above the surface – may seem less compelling when our perspective is kept closer to the ground. The concern of this book is to explain how and why English execution practices changed in ways that were often distinct, in both their timing and their character, from other parts of Europe and North America.

A second analytical vision that has been broadly ascendant in recent years maintains that changes in the letter and practice of English criminal law after 1750, a date once taken to signal the advent of humanizing trends, were in fact more distinctly regressive (or at least, non-progressive) than the pioneering work of Leon Radzinowicz and others seemed to suggest.Footnote 10 This outlook came to prominence with V. A. C. Gatrell’s The Hanging Tree (1994). One cannot read that remarkable book without feeling its compelling emotive force, particularly its insistence that the character and motives of reform advocates were not so unambiguously “good,” and their efforts on behalf of the condemned not so consistently energetic, as they were once presumed to be. The case for a more ambivalent record of progress has been reiterated in several recent studies of the Murder Act of 1752.Footnote 11 Stimulating as all these works have been, however, readers may come away from them with the impression that not much changed for the better – or even much at all – until 1830 at least.

The central concern of this book is to explain the remarkable shifts in the character, extent and frequency of executions in England between the Restoration and the twentieth century. In so doing, it endorses some of the insights of these works, while questioning others. By the early nineteenth century, English officials had become deeply divided by a struggle to redefine the scale, morality and effect of executions for crimes other than murder. On the one side was a traditional landed rural elite, determined to defend most of the old practices, albeit on a scale sufficiently reduced to minimize the powerful and persistent objections that had arisen to them. On the other was a new, urban-oriented (urbane) public culture that sought to eliminate execution for all crimes against property, as well as all prolonged modes of execution and post-mortem infliction.

Contexts

Whichever side of the social–cultural divide they stood upon, however, officials, at both the national and local levels, were the driving force of changes in execution practice.Footnote 12 These men were more immediately responsive to changes in the physical and moral circumstances of executions than their European counterparts. That responsiveness arose from at least five distinct and often overlapping features of public life that were either unique to England or at least uniquely powerful there: (1) a criminal law universally applicable throughout the realm, but enforced variably, from one time and place to another; (2) a parliamentary monarchy in which both royal government and a notably representative parliament were responsive to public opinion; (3) the unprecedented scale of urbanization in England from the seventeenth century onwards, which gave rise to an increasingly influential class of urban-based people who objected to prolonged execution displays in their midst, as well as the responses those displays provoked in working people; (4) a free and independent public press, which provided a vehicle for the sustained and increasingly powerful expression of these new “urbane” views; and (5) the size, and the political and cultural power, of London, which at certain critical junctures exerted a decisive influence on the conduct of executions throughout the nation at large.

A Single Criminal Law, Variably Enforced

Compared with other European states, England was to a unique degree effectively centralized under royal rule by the High Middle Ages. The oversight of criminal justice – the principle indeed that any crime was a violation of “the king’s peace,” rather than a purely personal wrong amongst his subjects – was embodied, by the middle of the twelfth century, in the establishment of eyres, wherein the king heard serious crimes in person in some parts of the country. In the thirteenth century the eyres gave way to assizes circuits, wherein royal judges, acting in the king’s name, often conducted trials and imposed capital sentences in most counties: every few years initially, and eventually twice yearly in all places except the north.Footnote 13

The system’s success was assured in part by the prominent role it assigned local elites in the administration of justice, both as judges in lesser causes at quarter sessions and as participants in determining the fates of capitally condemned offenders at the assizes. This blending of local influence and central authority was symbolically evoked, twice yearly, when the royal judges arrived at each county capital. They were greeted at the town’s boundary by the county sheriff and his many junior officials, a ritual enactment of “the subtle marriage of county authority and central power.”Footnote 14 Moreover, although England’s first two Stuart kings appear to have been particularly heavy-handed in using the judges to advance their agendas, this does not seem to have entailed any centrally directed policies as to hanging or pardoning capital criminals.Footnote 15 If a single, nationwide pardoning policy was being imposed at this time, explicit evidence of it has not yet been uncovered.Footnote 16

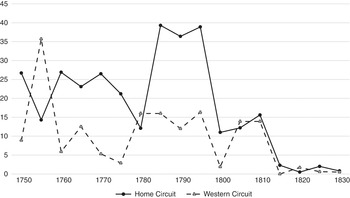

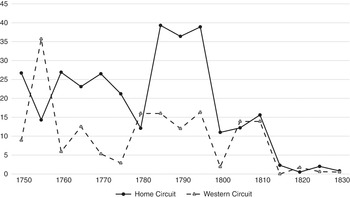

After the restoration of royal rule in 1660, there was a distinct retreat in the assertion of central control. The landed elites, whose position as “natural rulers” in the provinces had been jeopardized during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, were determined to regain lost ground, a determination broadly respected by royal government for at least a century and a half thereafter.Footnote 17 This system was formalized in 1728 when the government told the assizes judges that, henceforth, they should now submit lists of the names and crimes of the people condemned at each county assizes whom they believed should be pardoned and on what condition. From then until the substantial abolition of the “Bloody Code” a century later, the judges were required to provide detailed reasoning only in those few, subsequent cases where a petition was submitted on behalf of an individual convict whom they had left to be executed.Footnote 18 The two procedures have been characterized, respectively, as “administrative” (or “circuit”) and “petition” pardons, and the number of people covered by the former usually outnumbered the latter by a very wide margin (Figure 1.1).Footnote 19 After 1728 the judges’ rulings in “administrative” pardons were queried by the government only once. In July 1750, in the depths of the great crime wave that followed the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, three circuit judges were asked to provide detailed reasons for proposing to spare several convicted robbers when the times seemed to demand the maximum number of exemplary hangings. The government ultimately accepted the judges’ reasons.Footnote 20

Figure 1.1 Petition cases as a percentage of all pardon cases: Home and Western Circuits, 1750–1830 (five-year intervals).

This system has significant implications for how historians evaluate the social–economic character of pardoning because only the far less numerous “petition” pardons generated documents from which to discern the factors that informed judicial decision-making. The reasons underlying the greatest number of capital pardons in provincial England remain almost entirely unknown to us. Anecdotal evidence occasionally indicates that a personal intervention with a judge by provincial elites, at banquets or on other occasions during the assizes, could be decisive in the granting of an “administrative” pardon.Footnote 21 Government seems to have expected things to work this way. Such influence should not be too readily apparent, however. One judge on the Irish circuits in 1762 refused hospitality in the household of anyone who might have an interest in the fate of a capital convict at assizes because “the people will necessarily, and not without reason, … suspect, that those who are to administer the laws, on which their lives or properties depend, are under the influence of or partial to any great man of the country.”Footnote 22 Judges in England surely entertained such concerns as well. The law derived moral authority from the outward appearance of impartial administration.

Yet the hidden realities must sometimes – perhaps often – have been different. Another judge, in 1750, who supposedly confided to an official of the Oxford assizes that, in capitally convicting two men, “the jury had been more rigorous” than he thought justified, nevertheless stated that he “should be glad to have the names of half a dozen gentlemen of the neighbourhood to a Petition” for mercy in the case rather than intervene on his own initiative.Footnote 23 The extent to which personal connections led to pardon has been the subject of vigorous debate.Footnote 24 Determining the balance that prevailed in “administrative” pardons, between local imperatives on the one hand and consistent policy (either that of the government itself or an individual judge) on the other, remains one of the outstanding challenges for historians.

Local influence upon pardon decisions was not just a concession to the power of landowners in a nation where, until the late eighteenth century, agriculture was the central motor of the domestic economy. It was also a recognition that, in a still largely rural society, in which most labouring people moved only a few miles over the course of their lives, public punishments were inherently local displays.Footnote 25 It was scarcely surprising that execution was sought in September 1765 for two convicted robbers at Maidstone who, after being respited, had subsequently organized a gaol break in which the keeper was murdered. What was unusual was that, rather than await the next assizes, when the men would surely have been executed for the murder, the government got them hanged sooner by simply rescinding the respites for their earlier crimes. That unconventional tactic was justified on the grounds of making an example of the two men “with that Expedition so much desired by the [magistrates of the] County of Kent.” They were hanged in early December.Footnote 26 The (relative) speed of the example was deemed by local officials to be more important than a less timely display of maximum severity; had the two men been hanged for murder the following spring, their corpses would have been either dissected or gibbeted, as required under the Murder Act.

Regional variation in the enforcement of the “Bloody Code” was a consistent feature of the system. During the third quarter of the eighteenth century, the per capita rate of execution decreased in proportion to a county’s distance from London. Execution rates were highest in the capital, only slightly lower in the counties surrounding it (the Home Circuit), significantly lower beyond and, finally, almost non-existent on the Celtic periphery (Cornwall, Wales, Scotland). Some counties, particularly in the far north and west, went several years, even a decade or longer, without hanging a single person, and took pride in maintaining a conspicuously “unbloody” criminal code.Footnote 27 During the 1750s, the three counties of the Brecon Circuit in Wales condemned forty-one people to death for capital crimes against property, of whom only one was hanged. The comparative figures for London were 449 and 306.Footnote 28 Dramatic and sustained differences between counties, with interesting variations at specific times, continued all the way to 1830.Footnote 29

Striking as all of this is, however, proportions and per capita rates – the stock-in-trade of modern historians – may conceal from us the lived experience of execution. Contemporaries were only dimly aware at best of what proportion of the condemned was comprised by those whom they saw executed at any one place on any one day. The morality and effectiveness of capital punishment was evaluated in terms of the perceived significance and effect of the absolute number hanged on each occasion. Before the railways, few execution- goers ventured beyond the county in which they lived, and each execution day would have seen relatively few people hanged. Consider one mid-sized region of England, the six counties of the Norfolk Circuit, during 1785, probably the worst year for executions of the eighteenth century. Residents of Aylesbury (Bucks) saw two people hanged after the spring assizes and none after the summer. Bedford saw only one person hanged in the spring and none in the summer. Cambridge saw two people hanged in the spring and another two in the summer, Ipswich (Suffolk) two and three. The largest town on the circuit, Norwich, executed four people in the spring and three in the summer. No one was hanged at all in Huntingdon.Footnote 30 Even during the century’s worst year for executions, most people living in the provincial capitals of this circuit saw no more than four people hanged at once, though that number might have seemed unprecedented and awful to them.

Compare that with the experience of Londoners. Unlike the circuits, capital trials were held eight times per year at the Old Bailey and produced roughly the same number of execution days. On the eight regular execution days for 1785, Londoners saw twenty people hanged at once on the first occasion, five on the next, then nineteen, ten, five, eight, eighteen and finally nine. In all the provincial towns of England and Wales combined, more than twice as many people were hanged that year than the ninety-six in London.Footnote 31 But the sight and experience of execution in the capital was fundamentally different. Until the 1840s, the experience of execution, and the messages conveyed to most people who witnessed it, was essentially local in character.

Even the pardon system worked differently in London. Pardons for capital offenders were personally determined by the monarch and cabinet at a meeting with the Recorder of London, the senior judge and sentencing officer at the Old Bailey. Although the origins of the “Recorder’s Report” have been plausibly dated to the reign of William III, there is evidence that it was already practiced under Charles II.Footnote 32 By 1830, when the government was anxious to eliminate the procedure, its origins and rationale could not be determined; it was presumed to be an age-old privilege accorded the City of London, whose officials administered the Old Bailey. It was even speculated that the king might be obliged to determine capital cases in any county in which he happened to be present while the assizes were being held.Footnote 33 Perhaps the Report was a survival from the days before government was permanently situated in London, when an itinerant royal court enabled kings to decide legal causes in person.

Whenever and whyever it was begun, the Recorder’s Report gave pardon decisions in London a distinctly different character from those in the rest of the country. Personal intervention in individual cases appears to have been entertained far less often than in the provinces. Even so powerful a man as the Duke of Newcastle in 1734 was hard pressed to persuade his friend Lord Chancellor Hardwicke to pardon someone whom the Report had determined must die, because the latter doubted whether it was “proper to alter what was resolv’d Seriatim at the Cabinet, in the most solemn manner …, in a private method without calling another Cabinet.”Footnote 34 Perhaps, as Douglas Hay once suggested, the capital’s uniquely restive and transient criminal population rendered such personal interference (“a private method”) in pardon cases less desirable or effective than in the more traditionally hierarchical societies of the provinces.Footnote 35 Things were changing half a century later, though, when the sheer numbers of people being sent to the gallows in London provoked so much disapproval and disquiet that officials were more willing to change their minds about some cases between the Report and execution.Footnote 36

This points to another distinction between the conduct of pardon decisions in London and on the assize circuits, particularly by the late eighteenth century. Reading London’s vast periodical press, decision-makers at Recorder’s Reports must have felt a greater and more frequent moral pressure to change their minds. The assizes judges, by comparison, said the Lord Chief Justice in 1840, “have no peculiar facilities for observing the effect of their sentences.”Footnote 37 Leaving town long before the executions they ordered took place, they could exercise an “Olympian” indifference to their effects upon the local audience.Footnote 38 The men at Recorder’s Reports may not have felt so insulated from public reactions to their work.

A Constitutional Monarchy

By the 1660s, hanging decisions in provincial England were made in the context of a renegotiated balance of power between government and the landed elites who ruled local society. That balance shifted even more fundamentally after the Glorious Revolution of 1688–9, when parliament – the institutional embodiment of landed power at the nation’s political centre – made significant and permanent inroads into royal prerogative powers to a degree that had few parallels elsewhere.Footnote 39 The Revolution also inspired decisive changes in the scale, location and frequency of executions for treason, particularly in London, because three of England’s first four parliamentary monarchs – William III, George I and George II – were also foreigners who were anxious not to be seen emulating the bloody-mindedness of their English predecessors whenever rebellion had to be punished. The post-Revolution parliament was also, by European standards, a relatively democratic institution. Between 1689 and 1715, the electorate increased from about one-fifth to one-quarter of a million people – perhaps as many as one in every four adult men – and it went to the polls twelve times, a frequency unmatched before or since.Footnote 40 Parliament also showed itself to be closely engaged with the conduct of criminal justice, especially in and around London, passing a series of innovative laws that culminated in the Transportation Act (1718), a measure that ensured the regular and reliable imposition of a credibly severe and economically useful alternative to executions, which might otherwise have been deployed on an unacceptably large scale. As impressive and lastingly effective as such measures were, however, they also preserved the at least nominal application of the death penalty for crimes against property.

Nor did a relative degree of representative government necessarily ensure restraint in the expansion and enforcement of capital crimes: not when a substantial body of the propertied men whom parliament represented perceived their goods and their livings to be in danger. England’s newly constitutional monarchs and their parliamentary partners soon added the death penalty to two new categories of theft: shoplifting (1699) and stealing goods from within a dwelling (1713). Here too, the experience of London, with its unprecedentedly vast numbers of shopkeepers and of middle-rank employers of maid servants, was particularly influential.Footnote 41 Enthusiasm for the actual use of the gallows in such cases was also more marked in the capital, at least initially. Between 1722 and 1802 only about ten people in Surrey, perhaps 4 percent of those who had been convicted of either shoplifting or stealing in a dwelling, were hanged. During roughly the same period, London’s Old Bailey hanged just over 200 people for the same two crimes: roughly 20 percent of those convicted.Footnote 42

A more modern constitutional order, therefore, by no means ensured modern attitudes amongst the people whose interests it served. Conversely, some absolute monarchs of the late eighteenth century, impressed by Enlightenment writings, were willing to experiment with far more radical reductions in the death penalty than any yet contemplated in England. The promulgation of new criminal codes in Tuscany (1786) and Austria (1787), the former of which abolished execution for all crimes and the latter of which did so substantially, made a deep impression in England, given its historically high execution levels at that time.Footnote 43 What one absolute ruler might do, however, could as easily be undone by their successor, particularly in circumstances as alarming as the ensuing continental wars, which saw the death penalty restored in Tuscany and Austria alike.Footnote 44 Its entire abolition was perhaps too radical for the age. The Prussian Code of 1794, imposed by an equally authoritarian ruler, but also more advanced in its thinking than the English law of that time, proved a more lasting success in part because it preserved execution for murder and treason.Footnote 45 The more radical reforms attempted in Tuscany and Austria may have lacked a firm grounding either in public opinion or in the will of a substantially independent legislative body. By comparison, England’s conservative rulers of this latter era were only too aware that the abolition of the death penalty for any given crime against property, once sanctioned by public opinion and parliament alike, was to all intents and purposes irreversible. That was a key reason why the Tory governments of the early nineteenth century resisted such reforms so long as they did.

Urbanization and the Rise of Urbane Culture

English concerns about excessive bodily torments and execution displays were amplified, and new ones created, by two other great and closely linked transformations in English public culture which, like parliamentary monarchy, began in the middle of the seventeenth century and were accelerating dramatically by the turn of the eighteenth: the unique degree to which English people were increasingly living in towns and cities; and the emergence of an extensive and substantially free periodical press which particularly reflected (and enhanced) the concerns of urban dwellers. This urbane culture emerged in the capital soon after the Restoration. London – which in fact comprised two distinct cities: the City of London proper in the east; and the city of Westminster, county capital of Middlesex and home to parliament, in the west – was already one of the largest conurbations in the world. With almost 600,000 people in 1700, it was Europe’s second largest city after Paris; half a century and another 100,000 more people later, it was the largest. Sometime in the early nineteenth century, it reached more than a million; by the 1840s, two million.

More important even than London’s remarkable size, however, was the economic and cultural force it exerted in other parts of the country. Throughout the eighteenth century, London was home to more than one in every ten people in England, a proportion which no other major European city came close to matching. Eighteenth-century Paris contained only one in every forty French people.Footnote 46 One major factor in London’s extraordinary growth was that (with Amsterdam) it was one of only two European cities that were home to both the national government and the nation’s largest seaport. The vast commercial wealth of overseas traders, based in the City, had been crucial to parliament’s victory over the king in the 1640s.Footnote 47

Two changes after 1660 were particularly important to the issues explored here. First, the Great Fire of 1666 occasioned a massive rebuilding program that was accompanied by new concerns for more orderly urban space. Second, and even more decisive, was the establishment of annual parliaments – and the London “Season” – after 1688. Sustained annual residence in the capital of the greatest families of the realm (the peerage, who comprised the House of Lords), as well as their cadet branches and the gentry at large (who dominated the Commons), prompted a vast expansion of elite residential areas in Westminster, which had already been boosted by the migration thereto of many substantial residents of the City after the Fire.Footnote 48 The concerns of such metropolitan residents were manifest in the restraint of the worst excesses of treason executions by the 1690s and would later influence the removal of common executions from Tyburn in 1783.

The presence of parliament sometimes made London’s determinative role in English penal practices bluntly apparent. The Murder Act of 1752, which sought to confine post-mortem dissection solely to the bodies of convicted killers, specifically addressed itself to the needs of London’s College of Surgeons. And the time-honoured punishment for female traitors, to be burnt at the stake, was abolished throughout the realm in 1790 after its practice had become particularly frequent in London and offensive to its residents and officials. The social experience of the capital, in which all manner of propertied peoples lived close by one another, also reveals that, although the quintessential urban dweller might be middle class, “urbane” views were not confined solely to their ranks. The growing predilection for well-ordered urban space – and even, by the late eighteenth century, for the rigorous moral and spiritual self-discipline that many middling sorts came to see as its essential support – could also be found amongst the “gentry and the most virtuous of the aristocracy.”Footnote 49 On many occasions, this perhaps counterintuitive point will be of much significance in our account.

Although London inevitably led in the development of those concerns for order and decency in urban and suburban public space which prompted changes in the scale and practice of executions, there is room to question how forcefully or completely it shaped other urban cultures that were emerging in eighteenth-century England.Footnote 50 Other towns were also growing and becoming major centres of cultural aspiration. London’s already immense population doubled over the eighteenth century, but the growth rates of other towns were far larger: Bristol tripled; Plymouth quadrupled. Growth was even more spectacular in the industrializing Midlands and the north: Leeds was eight times larger in 1800 than in 1700, Birmingham nine times larger, Manchester twelve times larger, Liverpool fourteen times larger.Footnote 51 If a settlement of 5,000 people or more is the benchmark, approximately one in six English people lived in towns in 1700, nearly one in five by 1750, and nearly one in four by 1800. If we reduce the benchmark to only 2,500 people – the uppermost size of the small market towns that comprised about 85 percent of all urban settlements in 1700 – then town dwellers accounted for as many as one in three English people by 1800.Footnote 52 This extraordinary transformation made England’s experience unique. It accounted for an increasing proportion of all urbanization throughout Europe: one-third during the seventeenth century; more than half during the first half of the eighteenth century; and more than two-thirds during the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 53

This was surely a critical factor in explaining why the timing and character of penal change in England varied so distinctly in comparison with that on the continent. As other English towns came into their own as major economic centres, so too did their residents and governing classes start to act upon the same sorts of distaste for the indecencies of traditional execution rituals that first became apparent in London. Such people demanded and secured a dramatic decline in the per capita use of the gibbet during the second half of the eighteenth century. And, from 1783, county capitals followed London’s lead in altering the location and character of common executions. Some took two decades or more to do so; but, eventually, the ritual pioneered in London became the rule nationwide.

By the end of the eighteenth century, England’s urbane peoples, hitherto largely content to confine their political horizons to urban governance and philanthropy, were becoming a collective force in the public life of the nation at large. Overlapping to a substantial degree with the Evangelical religious movement, they questioned the moral fitness of landed elites to continue dominating government. The disastrous loss of the Thirteen Colonies after 1781 inspired not only the vigorous campaigns against the slave trade that would culminate in its abolition within two decades, but also a sustained attack upon the moral dissolution of the aristocracy and gentry. Their adulterous sexuality (eroding the foundations of society at its familial base), their gambling (evoking their disastrous inability to manage finances) and their readiness to fight duels with one another (signalling their reckless disregard for the sanctity of human life) were repeatedly lambasted in a now vast periodical press. A ruling elite so comprehensively unable to govern itself could not be trusted to govern others responsibly in dangerous times. The colossal scale of national participation in the Napoleonic Wars, which killed a greater proportion of the British people than any other conflict and imperilled the nation’s finances, at last determined urbane peoples to secure a permanent role in the governance of the nation.Footnote 54

Their indignant disapproval of the old order was also manifest in that sustained and ultimately successful attack on the “Bloody Code” which became a recurrent feature of public life after 1808. The very phrase “Bloody Code,” associated with ancient Greece’s fierce lawgiver Draco, seems first to have been applied to England’s vast array of capital statutes (“our bloody code, in which death haunts every page, and levels all degrees of crimes”) by an anonymous critic of overweening British power during that war with revolutionary America which first roused urbane people to action.Footnote 55 Its emotive character belied some paradoxes. Most of the more than 200 capital statutes in existence by 1808 had only been passed since 1720; indeed, most death sentences were imposed for a bare handful of offences – robbery, burglary, housebreaking, horse stealing – that had been capital crimes long beforehand. Only shoplifting and stealing in a dwelling were relatively recent additions. Moreover, although the code was largely consolidated between 1827 and 1830, the core capital crimes remained intact, though execution was all but entirely limited to murder and treason by 1837.Footnote 56 The belief of urbane critics that the aims of punishment – deterrence, retribution, even reformation – were best achieved when the letter of the criminal law was consistently enforced across all jurisdictions also heralded the end of that systemic regional variation in enforcement of the “Bloody Code” which the landed elites had sustained for at least a century.

A Uniquely Vigorous and Extensive Public Sphere

By then, the proportion of urban dwellers in England was twice that of France. But proportions do not tell the whole story: the absolute number of urban dwellers in France was in fact twice that of England.Footnote 57 The scale of urbanization in England alone does not entirely explain why its execution rituals changed at different times and in different ways from those in France and other European nations. The determination of the leaders of English urban society to effect such changes was given early, extra and sustained force by England’s unprecedentedly extensive and substantially unrestricted press, particularly in the form of newspapers.

As far back as the middle of the seventeenth century, a surprisingly large proportion of English people were at least functionally literate, demonstrating a capacity for reading – and others, a desire to be read to – that gave print culture a far greater vitality in shaping public life than prevailed on the continent.Footnote 58 Historians of Stuart England have detected the emergence of a “public sphere,” capable of articulating and focusing criticism of ruling elite culture, a century or more earlier than Jürgen Habermas famously proposed.Footnote 59 Yet there are still good grounds to argue that the eighteenth century saw a decisive acceleration in the volume, reach and effect of print media in England. Pre-publication censorship lapsed in 1695 and newspapers proliferated thereafter. During the second and third quarters of the century, there were nearly twenty papers in London at any one time, and thirty to forty in the provinces; by its end, there were more than twenty in London and eighty beyond. From the middle of the eighteenth century, the scope and variety of newspaper coverage and content was also increasing, with provincial papers becoming less dependent on their London counterparts for content and opinion.Footnote 60

Recent work on eighteenth-century France cautions us against underestimating the degree to which a periodical press was producing a vigorous public sphere there as well. But the differences were telling. England, with only one-third the population of France, had twice as many newspapers (or more) in circulation. Moreover, vigorous censorship laws ensured that much of the most radical print commentary in France had to be published abroad and circulated covertly.Footnote 61 In England, by comparison, official tactics for seeking to control the content of newspapers – seditious libel laws and other forms of prosecution – were usually deployed only after publication and were too irregularly enforced and controversial to have much effect. Late eighteenth-century governments sought to secure favourable coverage in some London papers by paying subsidies to their editors, but that strategy made little difference. The “independence” of the press was already an established public principle; and newspaper income from advertisements far outstripped anything the government could offer.Footnote 62

All this undoubtedly facilitated the emergence of a “bourgeois” public voice which developed the capacity and the confidence to challenge and reshape the character and structures of traditional aristocratic authority.Footnote 63 One centrally important facet of that challenge was a growing tendency to criticize the effectiveness of public executions, beginning around 1725. Given eighteenth-century England’s unique degree of urbanization, the groups attending common executions were growing visibly and alarmingly larger, especially in London. They grew larger still after 1830, by which time vast new industrial urban centres had surpassed the previous century’s provincial ones in size and vitality, while the advent of the railway enormously extended the geographical scope of attendance.Footnote 64 Recurrent professions of anxiety about the size and restiveness of the execution crowd, as well as contempt for its perceived indifference to any and all standards of civility and sympathy, were an inseparable concomitant of the rise of the press. Almost as soon as it was taking any critical notice of executions, the press was lamenting the ignorance and indifference of the crowd to their “moral lessons.”

This account concurs with Vic Gatrell’s rich and wide-ranging analysis of English execution crowds in most respects.Footnote 65 Although it seems impossible to believe that pre-eighteenth-century crowds did not sometimes defy official expectations of compliance with the ritual, frequent reports of subversive behaviour thereafter were as much – perhaps more – indicative of the anxieties and predispositions of the press’s largely urbane readership than of any real change in behaviour. As Gatrell insists, actual execution crowds were multi-faceted in character. Some attendees upheld the condemned in their final moments, some execrated them; some detested attending officials, others (if only by their silence) accepted their authority; some crowds were raucous, some seem to have been attentive; and so on. On only a few occasions – such as February 1807, when 30 people in a crowd of 40,000 outside Newgate were fatally crushed – can we be reasonably confident that indifferent or disorderly elements in the crowd outweighed a broad, if perhaps minimally sincere, popular acceptance of the official theatre of execution in England.Footnote 66

Yet we should also be attentive to ways in which print media served England’s rulers – landed elites and urbane peoples alike – by reinforcing public consciousness of the dangers of crime and the urgent need for effective punishments to counter it. A German visitor of the late eighteenth century found London newspaper accounts of executions to be suspiciously anodyne, observing that the papers “do their duty, by saying that most of the unhappy victims, that fell a sacrifice to the offended laws of their country, behaved with that decency which their awful situation required, and were, with pious prayers and ejaculations in their mouths, launched into eternity.”Footnote 67 This would have been a generally accurate observation during the 1760s and 1770s: but things changed thereafter. By the mid 1780s, critical commentary on executions and their effects, particularly in London, had become a regular feature of newspaper commentary. Whether it criticized executions or sought to uphold them, however, England’s vigorous and extensive press increasingly deployed detailed reportage and imaginative language to persuade readers that they were “attending” executions in as vivid and compelling a manner as did any actual crowd at the gallows. That cultural conviction would culminate after 1868 in a seemingly paradoxical – and ultimately unsustainable – effort both to conceal and to publicize executions.

That said, some newspapers do seem occasionally to have exercised self-censorship. The apparent choice of London’s two preeminent dailies, the Morning Chronicle and the Times, to omit any coverage at all of some executions during the French Revolutionary era might have been an effort to minimize public attention to a practice that might undermine propaganda asserting the superior humanity of English justice to that of France in the age of the Terror and then of the tyrant Bonaparte. Even if such omissions were a matter of deliberate editorial policy, however, crucial damage had already been done. The searing effect upon public opinion of large-scale executions in London and other towns during the 1780s had established the criminal law as a controversial feature of traditional English governance; and critical commentary on executions would return with unprecedented emotive force once their scale began to increase again after the wars ended. For all this, however, there is no evidence that English governments ever perceived press coverage of criminal justice as something to be censored. In fact, officials – perhaps especially in London – soon proved responsive to it.

*****

All these distinctive features of England’s public culture explain why major elements of that nation’s execution culture changed sooner – and sometimes later – than elsewhere. Recent scholarship rightly insists that we consider how far developments in England really were unique or uniquely advanced: but we should not overlook the real significance of important differences. Influential contemporaries such as Voltaire and Montesquieu were deeply impressed by the extent of constitutional monarchy in England, as well as by its freedom of print and commerce.Footnote 68 Historians should be as well. That said, the balance was shifting somewhat by the early nineteenth century. Knowledge of reforms implemented by overseas rivals, notably Revolutionary France and the new republic forged by Britain’s former American colonies, gave new force to demands that England should restrict not merely the enforcement of its “Bloody Code,” as it had largely done by 1789, but also its letter. That transition finally required the displacement of a traditionally ruling culture of landed elites, centred upon and serving the priorities of local variation, by a new urbane vision that demanded specificity in the law and its routine enforcement throughout the country. The groundwork for that change was substantial and well-established. It first became apparent in London, a century or more earlier, in the conduct of the most extreme modes of execution – those imposed upon traitors.