The most characteristic feature of the civilization of feudal Europe was the network of ties of dependence, extending from top to bottom of the social scale.

— Marc Bloch in Feudal Society (1968, p. 282)Few authors have described the pervasive nature of feudalism as vividly as French historian Marc Bloch in his seminal work. For centuries, feudalism was one of the most prominent and salient features of European economies. Nonetheless, its impact on microeconomic decision making, in particular during the High Middle Ages, remains empirically illusive. This paper presents the first quantitative evidence on the economy-wide significance of the eleventh-century English feudal system in facilitating agricultural cooperation and information sharing among feudal landowners and their managers.

The possibility of such interdependencies between Anglo-Norman manors has been suggested before by medieval historians. For instance, Wareham (Reference Wareham2005, p. 107) hypothesizes that inter-manorial connections, among other factors, could have led to efficiency gains in the production of grain, livestock, and other agricultural produce, “thereby leading to a rise in the valuation of the estates relative to their counterparts.” There are credible reasons to believe this was indeed the case in the High Middle Ages. Scholars working on later periods have found micro-level evidence of economic cooperation across English manors with respect to cattle management and transportation.Footnote 1 Furthermore, historical reconstructions of agrarian productivity have highlighted the importance of inter-manorial coordination in management decisions (Biddick and Bijleveld Reference Biddick, Bijleveld, Bruce and Overton1991; Karakacili Reference Karakacili2004). Such interactions plausibly led to information transfers along the feudal network. In his influential work on English medieval agriculture, Campbell (Reference Campbell2006, p. 421) writes that “much information and advice must also have been exchanged between manors belonging to the same estate, and estates belonging to the same religious order.”

Empirical evidence on the High Middle Ages is limited, however. The most comprehensive quantitative source on this period is Domesday Book, the kingdom-wide inquest of King William I into the economic state of Anglo-Norman England. However, econometric research on this source generally ignores the rich patterns of feudal landownership, instead modeling the manors as independent entities.Footnote 2 In the ensuing analysis, we take a different approach and allow for two plausible interaction mechanisms: scale and productivity spillovers.Footnote 3 In the former, production costs are cut by agglomeration effects, such as the efficiency gains arising from large-scale transport of agricultural produce among feudal peers. The latter are interpreted as productivity gains through common experiences with regard to successful management practices. Both mechanisms can be interpreted as external economies of scale, but now applied to feudal, instead of geographic, distance.

To disentangle these two mechanisms, we reinterpret the feudal system as a network in which manors are linked to one another based on their common ownership structure.Footnote 4 Making use of this feudal network, our empirical interaction model provides a rich, yet parsimonious, description of the interdependencies between manors, while also controlling for spatial autocorrelation through the geographic network. We argue that the sparse, non-overlapping nature of both networks allows us to separately identify the two economic mechanisms at hand, and to assess the relative contributions of feudalism and collocation. To construct the feudal network, we make use of the Hull Domesday Project database (Palmer 2010), which provides the most up-to-date identification of landowners in eleventh-century England. Identification of manors’ tenants-in-chief and lords allows us to link manors to one another based on their common ownership structure. The database also contains the monetary value, capital and labor resources, and location of each manor. The location is used to construct the geographic network, which allows us to control for spatial clustering. In addition, we impute environmental controls in the form of an agricultural suitability index.

Our results reveal that a manor’s prosperity, as expressed in terms of its value, was closely intertwined with the fortune of its feudal peers.Footnote 5 More specifically, this paper commences by presenting reduced-form evidence in the form of high correlations in capital and labor productivity among manors that were connected through feudal ownership. Next, we conduct a more structural approach, in which we model the economic nature behind these correlations by allowing for external economies of scale. This allows for the quantification of the aforementioned roles of spillovers in agricultural cooperation and human capital, respectively. We find that both mechanisms played a significant role in High-Medieval agriculture, although the latter (productivity spillovers) clearly dominates the former (scale spillovers) in terms of economic importance. Furthermore, we report evidence for similar external economies of scale through the geographic network of neighboring agricultural producers. Multiple sensitivity checks are presented to account for the possibility of network endogeneity, and for the obscurities in Domesday Book, highlighted by decades of Domesday scholarship.

Our contribution to the literature is threefold. First, we reinterpret and model the feudal system as an economy-wide network of interactions that impacts economic behavior at the microlevel. In doing so, we establish the existence of feudal coordination in the management of agricultural activities in the England of William the Conqueror. This sheds new light on the microeconomic decision-making of medieval economic agents, which is challenging to reconstruct (e.g., see Stone 2005). Our results underline the pervasive impact of institutional interactions on manors’ agricultural production decisions. From a broader perspective, we also contribute to the strand of research on how socioeconomic and political networks played a role in economic history. It is now widely recognized that such networks are central to the understanding of historical interactions in trade, business, and the diffusion of knowledge and technologies (see the overview by Esteves and Mesevage (2019) and references therein). Although it is a prime example of a network in economic history, no formal econometric analysis has ever been undertaken on feudal interactions.

Second, our analysis expands the understanding of how social interactions and, therefore, the transmission of information played a crucial role in the integration of medieval economies. Specifically, the existence of inter-manorial coordination across the kingdom points to the importance of accounting for institutional features of eleventh-century economies, as these could serve to propagate social interactions and knowledge throughout the country. It was long believed that information was scarce in pre-industrial economies, with transaction and information transmission costs being exacerbated by limited means of communication and transport. Over the past decades, however, economic history research has rehabilitated the role of medieval markets and commerce, establishing the idea of a commercial revolution in the long thirteenth century (for a notable example on England, see Britnell (1993)).Footnote 6 Reductions in transaction costs were considered to be an important driver of market activity in medieval times (Hatcher and Bailey 2001, p. 155). Nevertheless, it was only when literacy became more widespread in the thirteenth century that historical sources started to emerge to document such claims. Indeed, fourteenth-century purveyance accounts reveal that transport costs were “remarkably low” (Masschaele 1993, p. 266).Footnote 7 Furthermore, building on thirteenth-century price data, Clark (2015) has emphasized that grain markets were more integrated and efficient than previously thought. Evidence regarding transaction costs in the early periods of the High Middle Ages is more scarce though.Footnote 8 Our findings shed the first light on the idea that institutional features could serve to mitigate these costs.

Last, our empirical results contribute to the literature that provides a more nuanced view of medieval institutions. While feudalism might be detrimental to aggregate welfare, it also provided a platform through which common experiences on successful management practices and the efficient exploitation of manors’ production factors, be it their lands or their labor, were exchanged through the means of social interactions.Footnote 9 Others have successfully shifted attention away from the predominantly pessimistic views of medieval institutions. For instance, Epstein (1998) famously argues how medieval guilds emerged to provide a framework in which skills and technological innovations could be transferred. Such an argument draws comparisons with our interpretation of feudal interactions, which allow for the transmission of best-practice agricultural techniques. A contrasting view, however, emphasizes the inefficient nature of guilds, giving rise to rent-seeking and other economic growth-deterring behavior (Ogilvie 2004, 2019). Interestingly, a similar dichotomy lies at the root of the intense debate on whether feudal institutions were an efficient outcome, or rather a rent-seeking construction (for notable examples, see North and Thomas (1973) and Brenner (1976), respectively). The results in this paper indicate how feudal networks facilitated wealth accumulation of well-connected landowners within the institutional framework of feudalism, pointing towards its heterogeneous effects, even among the landholding elite.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the second section, we lay out the historical background. The third section introduces Domesday Book, discusses its main economic variables, and details its sample construction. In the fourth section, we argue for the need to incorporate the feudal network, a key and pervasive feature of medieval economies, in econometric approaches to economic decision-making during the High Middle Ages. The fifth section provides empirical evidence on the role of both the geographic and feudal networks, through reduced-form evidence as well as a more structural approach. The sixth section contains sensitivity analyses. The data and code to replicate the analyses in these sections are available in Delabastita and Maes (2023). Finally, the seventh section concludes.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Norman conquest of England was a landmark event in the history of Medieval Europe. Following the death of the childless Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor on 5 January 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, made a claim to the English throne. King Edward was, however, succeeded by Harold, his brother-in-law. This pressed William to gather an invasion fleet of French and Flemish soldiers, which landed in Sussex, southern England, on 28 September. On 14 October 1066, the English army of King Harold, who himself was killed in battle, suffered a decisive defeat to the Norman army. The decades that followed were characterized by a long and difficult period of consolidation. English lordship loyal to the former king were replaced by those who fought alongside William.

The eleventh-century England of King William I, later hallmarked as William the Conqueror, was organized by a feudal system in which landowners, that is, the tenants-in-chief, received land directly from the king in return for financial and military support. While this concept of knight service was long believed to be a Norman innovation (Round 1895, pp. 225–314), it is now established that the Anglo-Norman feudal system was strongly built on the foundations of ownership structures already in place (see Roffe (Reference Roffe2007, ch. 5) for a discussion). These landowners, who comprised both nobility and clerics, could in turn sublease their land to others, that is, the lords, or operate the landholdings themselves. Based on evidence from later periods (for instance, as argued in Biddick and Bijleveld (Reference Biddick, Bijleveld, Bruce and Overton1991) and Karakacili (Reference Karakacili2004)), this hierarchical network of landowners most likely played a defining role in the workings of medieval economies. Agricultural activities were organized around the landowners’ manors and were performed by various types of workers. Peasants were typically bound to the land on which they resided and often to its lords too, to whom they owed labor service.

Almost 20 years after his coronation, William the Conqueror announced an inquiry into the state of affairs in his kingdom. What followed was a remarkable exercise in central administration for its time. The kingdom was divided into (presumably) seven circuits, which were all visited by a team of commissioners. Tenants-in-chief were interrogated on the present and past ownership of their holdings, its values, its population, and the available economic resources, such as ploughs and livestock. Before their submission to the Exchequer in Winchester, local boards of four English and four Norman jurors were tasked with verifying the landowners’ answers.Footnote 10 The pervasive nature of the feudal hierarchy presents itself in the structure of the book, which was organized not on a geographic but on a feudal basis (Darby 1977, pp. 4–9).

The result is a historical document that showcases uniformity and geographic coverage incomparable to any other historical source in medieval Europe. Due to its definitive character, this “Book of Winchester” earned the name “Domesday Book” in the century to come (Harvey 2014, pp. 271–73).Footnote 11 Domesday Book presents researchers with a unique insight into the feudal structure of a medieval society and the functioning of contemporary rural economies. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that Domesday Book is far from a straightforward document. The original source is recorded in Latin and requires careful translation. Its layout, based on the feudal structure, makes it challenging to reconstruct the regional character of England’s population and agricultural activities. These challenges have brought forth a large literature of Domesday scholarship since the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 12 In what follows, we show how these fundamental contributions can be employed to construct a database fit for our econometric interaction model.

DATA DESCRIPTION

DOMESDAY DATABASE

We rely on the work of Palmer (2010) and his team on the Hull Domesday Project (HDP). This data set provides a comprehensive overview of all manors in 1086 England, their resources, as well as their value in shillings at the time of the Conquest, 1066, and at the time of the inquest, 1086. To achieve this, the recorded resources of all seven circuits were carefully distributed across manors. Other translated and digitized versions of the Domesday Book exist, but the HDP database is the only version that is constructed with statistical analysis in mind.

The HDP database also contains a comprehensive list of all Domesday landowners in 1066 and 1086. Importantly, they identified and standardized a majority of the 1086 landholders.Footnote 13 In the presence of inconsistent reporting of personal names, a phenomenon that should be expected given the historical nature of the source at hand, this is of crucial importance. In this effort, the Hull team was supported by decades of work by preceding Domesday scholars.Footnote 14 It is safe to assume that this is the closest one will ever come to reconstructing a complete feudal system for economic analysis.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, it is still worth emphasizing that network mismeasurement and selection bias are important considerations in this context. We will return to these issues in our sensitivity analysis.

MANORS’ RESOURCES

Economic activities in English manors around 1086 mainly involved growing crops and raising animals. Domesday Book illustrates that especially arable farming, that is, the cultivation of crops,Footnote 16 was of high importance: the number of plough teams and ploughs needed to bring the manor to full production capacity received a central place in the inquiry. In contrast, the livestock counts were redacted from the final version of the Great Domesday Book.Footnote 17 In this context, we specify the resources that could explain the variation in wealth across manors.

A first resource important to production was the availability of labor. Domesday Book provides an intricate categorization of laborers depending on their legal status, ranging from the liberi homines (free men, not bound to land) to slaves. Following Walker (2015), we simplify this subdivision by making the distinction between slave labor and all other forms of labor.

The high reliability on the cultivation of crops implies that ploughs and land were inputs of high importance. Recent empirical research has highlighted the crucial impact of plough technologies on long-run agricultural productivity (Andersen, Jensen, and Skovsgaard 2016). Domesday Book records the number of ploughs available at each manor. In addition, both the quantity and quality of its land were essential to the determination of a manor’s value. Domesday Book is the only medieval source that casts a light on the amount of arable land, albeit a very oblique one (Campbell 2006, pp. 386–87). Landowners were asked the extent of their manors in terms of a measure called ploughlands, defined as land for so many ploughs. In theory, this is a straightforward measure of arable land. Despite its simplicity, the ploughlands variable is one of the most disputed pieces of information in Domesday Book, with scholars highlighting inconsistent reporting and the infamous phenomenon of “overstocking” (i.e., manors where the amount of ploughs exceeds the number of ploughlands). Moreover, little consensus exists on whether the ploughlands should be considered a measure of land or rather a fiscal measure (Roffe Reference Roffe2007, p. 203). For the purpose of our analysis, we propose the following way forward. In our main estimates, we use the ploughlands variable as stated in Domesday Book. In addition, we conduct a robustness check, in which we assume that land is a perfect complement to the other two key determinants of manor wealth, capital and labor, discarding the need for a land quantity variable.Footnote 18

With respect to the quality of the land involved, we link the locations of the Domesday manors with a contemporary GIS database on the suitability of English lands for agriculture. The former are identified by the Palmer team, with their coordinates being approximated to the nearest kilometer. For the latter, the Global Agro-Ecological Zones (GAEZ) project (Fischer et al. 2012) provides environmental suitability indices for a variety of crops. To approximate eleventh-century agricultural conditions as closely as possible, we use the GAEZ classification for barley suitability under the assumption of traditional management, that is, the usage of only labor-intensive techniques without the application of nutrients, irrigation, or other contemporary techniques.Footnote 19

SAMPLE SELECTION

Finally, we impose a series of plausible and non-mutually exclusive sample conditions.Footnote 20 Table 1 presents the number of cases and frequency for each of the sample conditions. The impact of alternative sample selection and identification rules is discussed in the sixth section.

First, as this analysis only concerns landholdings that are economically active, we exclude manors that did not generate any value.Footnote 21 Consequently, we are solely concerned with economic decisions on the intensive margin rather than the extensive margin. The mechanisms underlying the latter decisions are likely to have been fundamentally different, and an integrated analysis would require an alternative approach, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Second, both labor and capital resources have to be recorded in the data. Likewise, we exclude observations with missing values for the ploughlands variable from our main analysis. Third, a manor may refer to more than one place. For our main analysis, we restrict the sample to single-location manors. Multi-location manors only represent a small fraction of the sample, and as we later show that their inclusion changes little to our findings. Finally, the landowners of about 15 percent of all manors in Domesday Book are unidentified. As these manors’ lords were presumably less important landholders, we assume that these are unique to the manor and, therefore, do not have other possessions other than that specific manor.

Table 1 NUMBER OF CASES AND FREQUENCIES OF THE SAMPLE CONDITIONS

Note: All frequencies are with respect to the original HDP database. The sample conditions are not mutually exclusive.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

A NETWORK APPROACH TO FEUDALISM

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE FEUDAL NETWORK

We will argue that an econometric approach to Domesday Book should account for the feudal reality of economies in the High Middle Ages. It has already been emphasized that the seignorial economy was organized on the foundations of the Anglo-Norman feudal system. Manors with shared ownership are likely to have interacted in an economic sense. Indeed, evidence from the Late Middle Ages reveals that feudal peers cooperated closely in various aspects of microeconomic decision-making, such as agricultural activities and the transport of goods, as previously outlined. In other words, interactions among feudal peers were conducive to the integration of manorial economies.

There are other reasons to believe that this was the case, aside from historical evidence from later periods. In his micro-study of medieval farm management techniques, Stone (2001) emphasizes the role of the information constraints that farm managers faced when making crucial economic decisions. It is in such a context that information-sharing among manorial peers should have been very impactful. What kind of management practices would have been shared across the feudal network? A first and obvious candidate is the diffusion of innovative technologies across Domesday England. Due to their public nature, innovations can be easily diffused through local and social networks.Footnote 22 As a result, learning from peers has been identified as a key driver in the adaptation of new agricultural technologies.Footnote 23 Historical evidence on knowledge spillovers in early twentieth-century agriculture similarly highlights the importance of interaction among neighbors and social peers alike (Parman 2012).

It is now generally accepted that technological progress in medieval agriculture was a gradual process with little room for macro inventions. Instead, agricultural progress materialized through “a long chain of small improvements” (Persson 1988, p. 28), such as the emergence of mixed-farming systems, crop rotation, and the supportive use of livestock farming.Footnote 24 There must have been great variation in the extent to which manorial managers were able to adapt and apply these new best-practice techniques successfully. In such a context, the institutionalized interaction between a heterogeneous set of feudal landholders has great potential to materialize spillovers of agricultural knowledge.

Additionally, feudal clustering of higher levels of labor intensity, or even labor exploitation, could occur.Footnote 25 Such an interpretation would align closely with Marxist theories of feudalism, in which the exploitation of unfree peasants and the disregard for technological progress are inevitable consequences of the feudal class structure. For example, Brenner (1976) (in)famously states that “the lord’s most obvious mode of increasing output from his lands was not through capital investment and the introduction of new techniques, but through ‘squeezing’ the peasants, through raising either money-rents or labour-services.” In the context of our empirical approach, this implies that feudal peers share great similarity in the extent to which they “squeeze” their respective manor’s inhabitants.

In summary, there are credible reasons to believe that the pervasive nature of feudal society also affected a wide range of microeconomic decisions in the High Middle Ages, ranging from information transmission to agricultural cooperation.Footnote 26 In what follows, we reconstruct the feudal network of King William I. This will later allow us to unearth feudal interdependencies in Domesday Book, both in a reduced form and in a more structural framework.

FEUDAL NETWORK

To study the feudal interdependencies across Domesday manors, we represent the feudal system of William the Conqueror as one comprehensive network composed of various linked neighborhoods. Manor j is defined to be in the feudal neighborhood

![]() $${{\cal F}_i}$$

of manor i either when they share the same tenant-in-chief (condition (i)) or lord (condition (ii)), or when the tenant-in-chief of one manor is the lord of the other (condition (iii)). Formally, we can write these three conditions as:Footnote 27

$${{\cal F}_i}$$

of manor i either when they share the same tenant-in-chief (condition (i)) or lord (condition (ii)), or when the tenant-in-chief of one manor is the lord of the other (condition (iii)). Formally, we can write these three conditions as:Footnote 27

$$j \in {\mathcal{F}_i} \unicode{x21D4} \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

\text {(i) tenant-in-chief of $i$ = tenant-in-chief of $j$, $or$} \hfill \\

\text {(ii) lord of $i$ = lord of $j$, $or$} \hfill \\

\begin{gathered}

\text {(iii) tenant-in-chief of $i$ = lord of $j$, or tenant-in-chief of} \hfill \\

\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! j = \text {lord of $i$}. \hfill \\

\end{gathered} \hfill \\

\end{array} } \right.$$

$$j \in {\mathcal{F}_i} \unicode{x21D4} \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

\text {(i) tenant-in-chief of $i$ = tenant-in-chief of $j$, $or$} \hfill \\

\text {(ii) lord of $i$ = lord of $j$, $or$} \hfill \\

\begin{gathered}

\text {(iii) tenant-in-chief of $i$ = lord of $j$, or tenant-in-chief of} \hfill \\

\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! j = \text {lord of $i$}. \hfill \\

\end{gathered} \hfill \\

\end{array} } \right.$$

One can represent the entire feudal network compactly in terms of a symmetric feudal network matrix F:

$${\bf{F}} = \left[ {{f_{ij}}} \right],{\rm{\;}}{f_{ij}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}{1,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \in {{\cal F}_i},}\\{0,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \notin {{\cal F}_i}.}\end{array}} \right.$$

$${\bf{F}} = \left[ {{f_{ij}}} \right],{\rm{\;}}{f_{ij}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}{1,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \in {{\cal F}_i},}\\{0,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \notin {{\cal F}_i}.}\end{array}} \right.$$

EXAMPLE

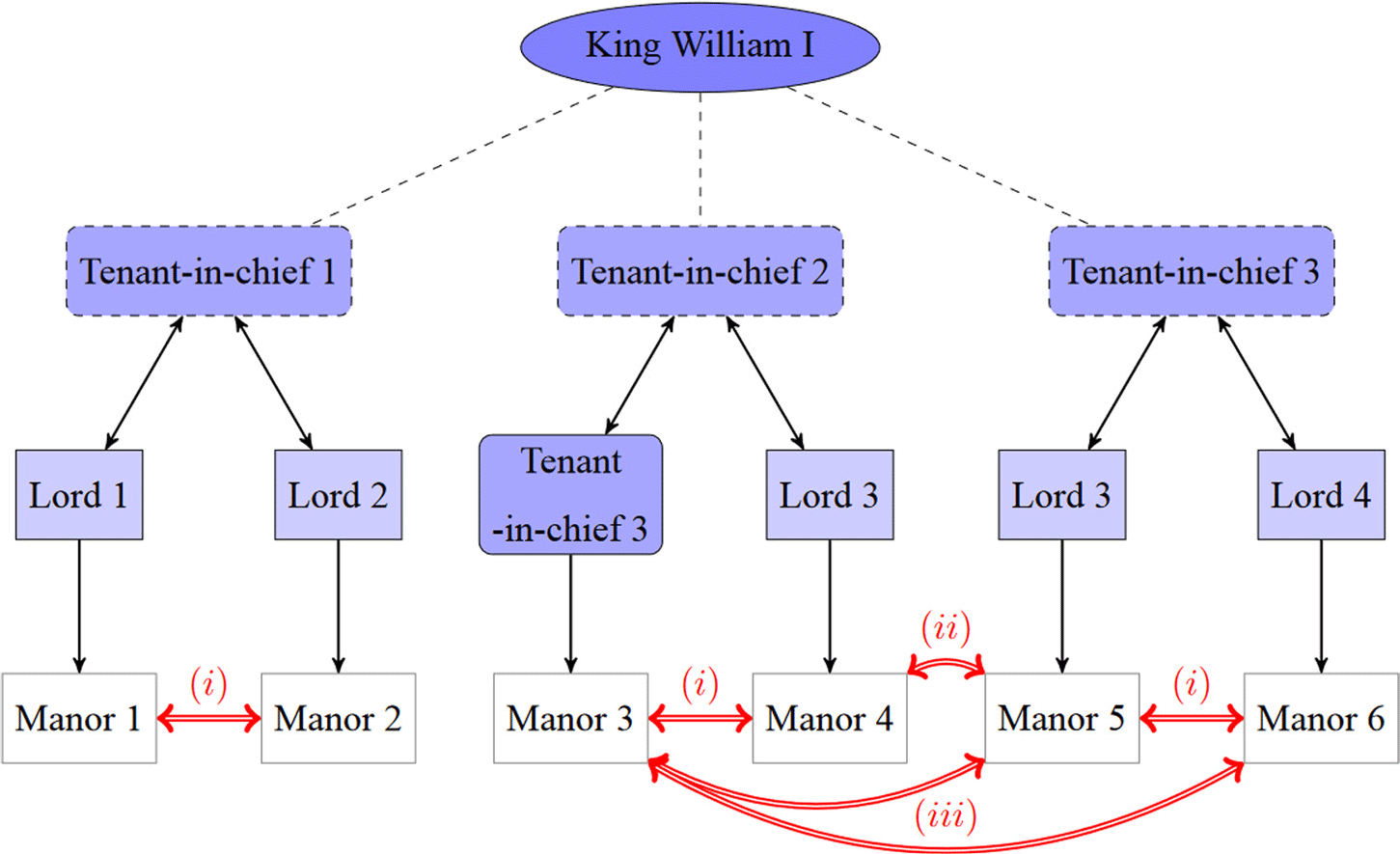

We illustrate these concepts with an example of a feudal system, presented in Figure 1, in which three tenants-in-chief own all of King William’s lands. The three landowners in turn sublease their lands to two lords. These could also be tenants-in-chief themselves, as is the case for manor 3. Since this construction was not uncommon in eleventh-century England, let us consider the neighborhood of manor 3. In our set-up, manors 3 and 4 are connected because of condition (i), that is, they share the same tenant-in-chief. As manor 3’s lord is also the tenant-in-chief of manors 5 and 6, condition (iii) implies that manor 3 is connected to manors 5 and 6 as well. As a result, elements in the third row (column) of matrix F will be equal to one in the fourth, fifth, and sixth column (row).

Figure 1 A SIMPLIFIED EXAMPLE OF THE ANGLO-NORMAN FEUDAL NETWORK

Notes: ⇔ arrows represent links (i.e., edges) in the network.

Source: Authors’ illustration.

Applying these definitions to the feudal system as recorded in Domesday Book, we (re)construct the feudal network of eleventh-century England. In this network, about 68 percent of the 1,550,125 links across Anglo-Norman manors are generated by the fact that manors share a tenant-in-chief, that is, condition (i). Lords were largely dedicated to a specific tenant-in-chief, with only about 2 percent of the edges rooted in condition (ii). In other words, lords were mostly, but not exclusively, confined to the subtree of their tenant-in-chief, like manors 1 and 2 in Figure 1. This is intuitive, given those lords were expected to swear an oath of fealty, and to attend their vassals’ private courts for advice (Dyer 2009, p. 86). Alternatively, tenants-in-chief were connected across subtrees of the network and leased property from other tenants-in-chief in the remaining 30 percent of the cases.

At the level of the manor, the size of the feudal neighborhood (i.e., degree) shows great variation. On average, a Domesday manor is connected to 136 other manors. Half of the manors, however, have a degree of 59 or less. In other words, the mean degree is skewed by a selection of well-connected manors owned by important landowners. In Online Appendix A, Tables A2 and A3 present the most influential tenants-in-chief and lords, respectively, in terms of the size of their estates.

GEOGRAPHIC NETWORK

To fully account for the importance of regional effects, we also construct a geographic network. The resulting matrix G controls for the distance between all manors in our sample. The idea is that neighboring manors were more likely to interact and cooperate, and could more easily observe each others’ successful and failing management practices. Such synergies between two farms i and j become less likely when the distance d i,j increases between them. To capture this, we construct a matrix using double power distance weights,

$${\bf{G}} = \left[ {{g_{ij}}} \right],{\rm{\;}}{g_{ij}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}{{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {{d_{i,j}}/d} \right)}^2}} \right)}^2},}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \in {{\cal G}_i},}\\{0,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \notin {{\cal G}_i},}\end{array}} \right.$$

$${\bf{G}} = \left[ {{g_{ij}}} \right],{\rm{\;}}{g_{ij}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}{{{\left( {1 - {{\left( {{d_{i,j}}/d} \right)}^2}} \right)}^2},}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \in {{\cal G}_i},}\\{0,}&{{\rm{\;if\;}}j \notin {{\cal G}_i},}\end{array}} \right.$$

where the distance parameter d implicitly defines the magnitude of the spatial neighborhood under consideration: that is,

![]() $j \in {\mathcal{G}_i}\, \unicode{x21D4} \,{d_{i,j \,}\unicode{x2A7D} } \,d$

. If the distance between the two farms is larger than d, the influence becomes zero.

$j \in {\mathcal{G}_i}\, \unicode{x21D4} \,{d_{i,j \,}\unicode{x2A7D} } \,d$

. If the distance between the two farms is larger than d, the influence becomes zero.

To obtain our main results, we set the distance parameter equal to 20 km.Footnote 28 The choice of spatial weights is always arbitrary to an extent, thus we mitigate such concerns by a range of robustness checks. These will be discussed later. With the construction of matrices F and G, we now have the tools to comprehensively incorporate the feudal nature of the manorial economy in our analysis.

NETWORKS AND MANORIAL PROSPERITY

Manorial Values and Resources

Following the majority of pre-existing empirical work on Domesday Book (for the earliest example, see McDonald & Snooks (1985)), we commence by establishing the relationship between the value y i of manor i and its resources x i (i.e., number of non-slave and slave laborers, the number of ploughs, and ploughlands), all expressed in logarithms. In addition, x i includes county and soil quality dummies. For now, we assume that manors in eleventh-century England operated as separate, individual entities, regardless of their position in the feudal system. The following baseline equation can then be estimated using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS),

where

![]() ${\varepsilon _i}$

can be interpreted as unexplained productivity. The left-hand side of Equation (1) is expressed in shilling prices, in contrast to the right-hand side, which is expressed in quantities. In case of a constant ratio of prices of capital and labor across the Anglo-Norman kingdom, our estimate of

β

is unaffected.Footnote 29 If one assumes that a manor’s value is determined by its agricultural production, it is easy to interpret Equation (1) as a Cobb-Douglas production function, in which

β

represents the output elasticities of the respective resources.Footnote 30

${\varepsilon _i}$

can be interpreted as unexplained productivity. The left-hand side of Equation (1) is expressed in shilling prices, in contrast to the right-hand side, which is expressed in quantities. In case of a constant ratio of prices of capital and labor across the Anglo-Norman kingdom, our estimate of

β

is unaffected.Footnote 29 If one assumes that a manor’s value is determined by its agricultural production, it is easy to interpret Equation (1) as a Cobb-Douglas production function, in which

β

represents the output elasticities of the respective resources.Footnote 30

Table 2 presents the correlational relationship between the manorial values and the resources recorded in the Domesday Book. Our results can be easily compared with earlier analyses at the local level, such as the ones in McDonald and Snooks (1986) for the counties of Essex and Wiltshire, as well as with the more recent work of Walker (2015), who was the first to estimate a similar relationship at the national level. Just like these studies, we observe a strong relationship between manorial resources and their values. The availability of ploughs as a capital good played a crucial role in determining a manor’s economic value in each of the respective specifications. Labor that was not fully bound to the lord’s ownership had a somewhat higher effect on the manorial income than slave labor.Footnote 31

Table 2 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MANORIAL VALUE AND RESOURCES (OLS)

Note: All variables are in logarithms. The reference category for the land suitability variable is “moderate.” Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Source: Authors’ estimations.

The inclusion of ploughlands as a land quantity measure in Specifications (2) and (4) has only a minor impact on the interpretation of our results. This is to be somewhat expected, given the highly collinear nature of the ploughs and ploughlands variables. In addition to previous work, we include a categorical soil quality variable in all our specifications. Lands unsuitable for agriculture were valued substantially lower in Domesday Book, consistent with the agriculture-minded interpretation of said source. On the other hand, we do not observe an economically meaningful difference between the valuations of moderately and highly suitable lands. This can be attributed to limitations in agricultural know-how during the High Middle Ages, rendering farmers unable to exploit the additional gains that might come from these highly suitable lands. The inclusion of county fixed effects in Specifications (3) and (4) appears to absorb most of the geographic environment effect. This explains why our coefficients are relatively comparable to previous estimates that assume a similar, linear relationship. Footnote 32 Also, this reveals that the results in this paper are not contingent on the soil suitability controls.

Reduced-Form Evidence on the Role of Social Interactions

Before extending the linear specification discussed in the fifth section, we present some correlational evidence that supports the hypothesis that there was a significant degree of economic interaction through the feudal network. We consider two measures of economic productivity: the value-to-labor and value-to-capital ratios.Footnote 33 For each measure, we regress the manor’s own ratio on the average ratio of the manors in its feudal or spatial neighborhood, controlling for agricultural suitability and county fixed effects. This exercise allows us to assess correlation through the feudal network without making structural assumptions. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3 CORRELATIONS ACROSS THE FEUDAL AND SPATIAL NETWORK (OLS)

Note: All ratios are in logarithms. The correlations are calculated on the subsample of manors for which the average peer ratio is non-zero. Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Source: Authors’ estimations.

We find that the value-to-resource ratios, which can be loosely interpreted as factor productivity, are highly spatially correlated across medieval England (Columns (1) and (2)). Common determinants of agricultural productivity are a likely explanation for such a pattern, as controlling for agricultural suitability and county level effects only absorb part of the spatial correlation. Crucially, we also find highly correlated value-to-resource ratios across the feudal network (Columns (3) and (4)). Interactions with feudal peers were only half as important as those with neighbors. If we only consider feudal peers located more than 20 km away in the calculation of the average peer ratio (Columns (5) and (6)), the ratios are still highly correlated and significant, which suggests that the correlations across the feudal network are not merely driven by geographic proximity.

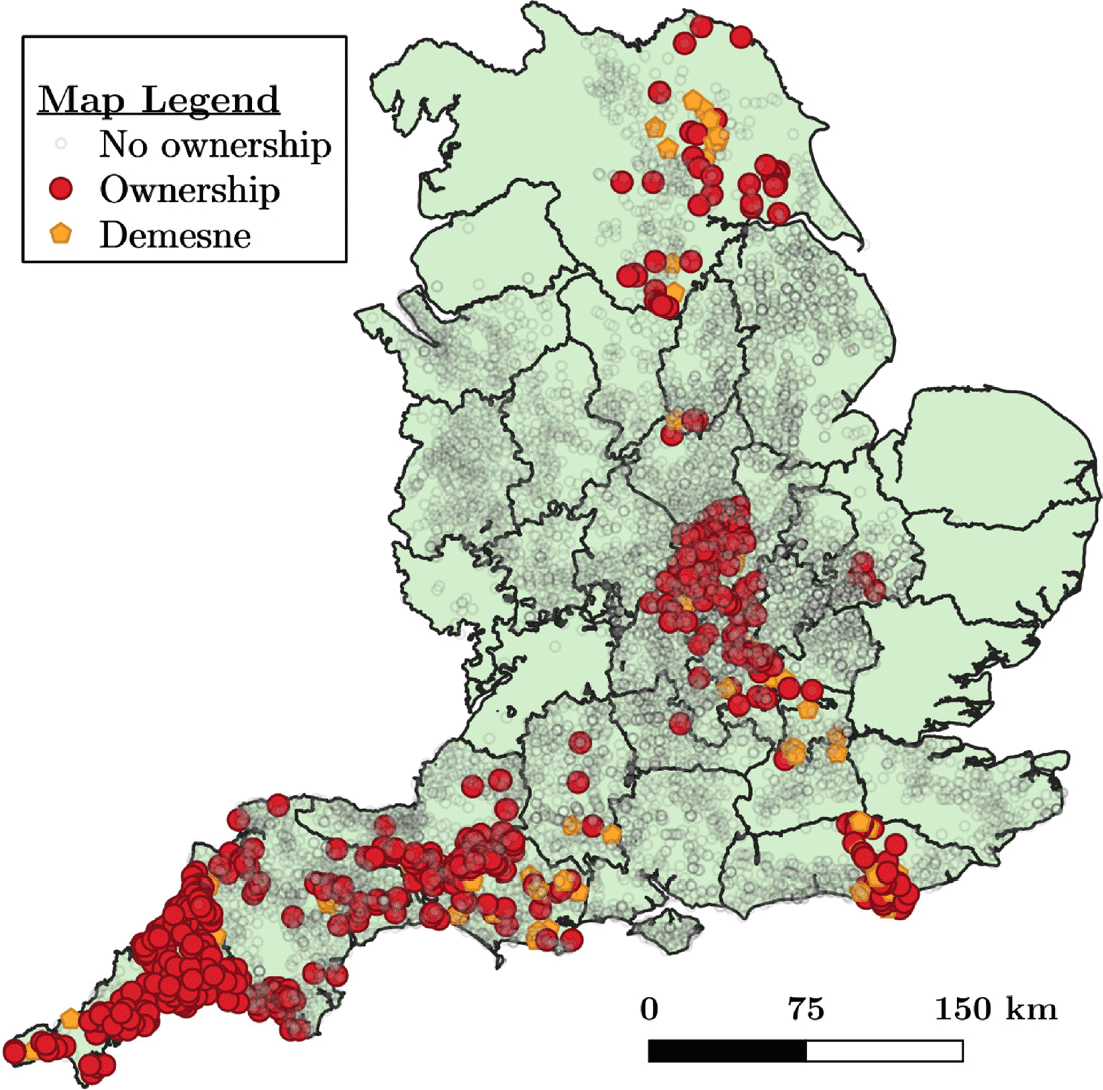

Given the empirical importance of both spatial and feudal connections, an important challenge in identifying the role of feudal networks is to distinguish their effects from those of the spatial network. If the feudal and spatial networks were identical, it would be impossible to differentiate the roles of the former from the latter. Fortunately, manors with common ownership were scattered throughout eleventh-century England. For instance, Fleming (1991, p. 180) describes how Norman holdings in Yorkshire did not form “any sort of compact territory.” This regional variation can be easily demonstrated by looking at the geographical spread within a single estate. In Figure 2, we present the example of the estate of Robert, Count of Mortain, who was a major landowner in Domesday England.Footnote 34 It is clear that his estate was scattered all over the kingdom, a characteristic that was not rare in Anglo-Norman England (e.g., Dyer 2009, p. 82). In conclusion, this stylized fact of the feudal network enables us to compare manors with similar location endowments but distinct feudal characteristics (and vice versa), and to examine the impact of the latter on the holding’s value.

Figure 2 ESTATE OF THE COUNT OF MORTAIN

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Palmer (2010); historical county borders from Brookes (2017).

Structural Evidence on the Role of Social Interactions

In this section, we introduce a structural interaction model that provides a rich, yet parsimonious, description of the feudal interdependencies between manors, while also controlling for spatial autocorrelation through the geographical network.Footnote 35 The model enables us to assess the relative contributions of the feudal and geographical networks on external economies of scale. Moreover, it allows us to decompose these economies of scale into a productivity and scale spillover effect.

CHANNELS

In line with the earlier highlighted historical evidence (see the fourth section), we hypothesize two channels through which feudal interactions could have taken place, and modify Equation (1) accordingly. First, we consider the possibility that human capital was shared among feudal peers in the form of productivity spillovers. In the information-constrained world of Domesday England, public knowledge about agricultural micro-inventions could have easily transferred through institutionalized interactions of related landowners. In a specification such as Equation (1), this implies that the error terms are correlated across the feudal network.

Second, we allow for the possibility of scale spillovers among connected manors. Such spillovers arise when the feudal or geographic clustering of large-scale manors, in the form of high values of y i, induces a reduction in production costs. For instance, neighboring high-value manors could more easily cooperate to provide public infrastructure, such as bridges, facilitating even higher agricultural production. While we expect such coordination to be more important for the geographic network than for the feudal network, such mechanisms might also arise among feudal peers. This becomes particularly clear in the context of the bridge example, as Cooper (2006, p. 66) describes how bridgework evolved from a communal obligation under the Anglo-Saxons to a highly feudal affair under the Normans.

Another way feudal interdependencies could potentially play a role is through the pooling of resources, captured in the vector x i. However, there are historical reasons to believe that this was implausible. It is unclear how certain manorial values, such as land, would have a direct effect on a feudal peer’s agricultural activities. While other resources, such as labor or plough teams, could plausibly have been shared, we argue that this is unlikely. Such interactions would be highly constrained by the feudal network, as these resources had limited mobility. Moreover, harvest periods were highly time-constrained, meaning resources were indispensable to the manors they belonged to.

MODEL

In our structural network model, we again specify the value y i of manor i as a linear function of its resources x

i and an unobserved error term ε i. In contrast to the reduced-form model in Equation (1), we now allow a manor’s value y i, and its unobserved productivity ε i, to depend on the values and unobserved productivity of the manors in its feudal neighborhood

![]() ${{\cal F}_i}$

, and geographic neighborhood

${{\cal F}_i}$

, and geographic neighborhood

![]() ${{\cal G}_i}$

.Footnote 36 This allows our model to capture and disentangle the two aforementioned channels of scale spillovers and productivity spillovers.

${{\cal G}_i}$

.Footnote 36 This allows our model to capture and disentangle the two aforementioned channels of scale spillovers and productivity spillovers.

In particular, we assume that the value y i of a manor i depends on not only its own resources x i, but also on the average value of its peers in both neighborhoods and an unexplained productivity term ε i,

$${y_i} = \alpha + {\bf x}{_i}{\beta ^{'}} + {\delta _F}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{f \in {\mathcal{F}_i}} {y_f}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{F}_i}} \right|}} + {\delta _G}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{g \in {\mathcal{G}_i}} {y_g}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{G}_i}} \right|}} + {\varepsilon _i},$$

$${y_i} = \alpha + {\bf x}{_i}{\beta ^{'}} + {\delta _F}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{f \in {\mathcal{F}_i}} {y_f}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{F}_i}} \right|}} + {\delta _G}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{g \in {\mathcal{G}_i}} {y_g}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{G}_i}} \right|}} + {\varepsilon _i},$$

in which β denotes the direct effect of the manor’s resources and δ F (δ G) captures scale spillovers from feudal (geographic) neighbors. The unexplained productivity term ε i in turn depends on the manor’s innate productivity η i and the average unexplained productivity of its peers in both neighborhoods,

$${\varepsilon _i} = {\lambda _F}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{f \in {\mathcal{F}_i}} {\varepsilon _f}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{F}_i}} \right|}} + {\lambda _G}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{g \in {\mathcal{G}_i}} {\varepsilon _g}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{G}_i}} \right|}} + {\eta _i},{\text{}}\mathbb{E}\left[ {{\eta _i}\mid {\bf X,F,G}} \right] = 0,$$

$${\varepsilon _i} = {\lambda _F}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{f \in {\mathcal{F}_i}} {\varepsilon _f}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{F}_i}} \right|}} + {\lambda _G}\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{g \in {\mathcal{G}_i}} {\varepsilon _g}}}{{\left| {{\mathcal{G}_i}} \right|}} + {\eta _i},{\text{}}\mathbb{E}\left[ {{\eta _i}\mid {\bf X,F,G}} \right] = 0,$$

where λ F (λ G) captures spillovers in productivity from feudal (geographic) neighbors.Footnote 37 This model can be rewritten compactly in matrix notation:

In this expression, F and G are adjacency matrices as defined in the previous section.Footnote 38 This model can be estimated consistently and efficiently by using the generalized spatial two-stage least squares (GS2SLS) procedure proposed in Kelejian and Prucha (2010) and Drukker, Egger, and Prucha (forthcoming). This procedure accounts for the endogeneity caused by the inclusion of the scale spillovers (i.e., the dependent variable y also appears on the right-hand side), by using the network lags of manors’ resources as instruments.Footnote 39

The interpretation of the coefficients in our model is less straightforward than that of those in an OLS regression. In general, the parameters cannot be understood as marginal effects, as the latter also depend on the underlying network structure. Consider, for example, the simple network with three nodes that is depicted in Figure 3, where manor j is connected to manors i and k but manors i and k are not connected. If an exogenous shock shifts manor i’s innate productivity η i with Δ, its productivity ε i initially (in step s1) also rises by this amount. In the next step, due to the feudal structure, its direct feudal peer j will experience an effect on its productivity ε j, but now of size λΔ. The same mechanism again induces a productivity spillover of size λ 2Δ to manors i and k in step s3. This mechanism goes on forever, but the additional terms become negligibly small as the number of steps increases. We also note that the further away a manor is from the feudal network, the smaller the effect becomes. A similar mechanism is at work when a shock in x i or ε i (the latter caused by a shock in η) changes the value of y i.

Figure 3 AN ILLUSTRATION OF PRODUCTIVITY SPILLOVER IN THE STRUCTURAL MODEL

Source: Authors’ illustration.

To overcome this difficulty, we report the easier-to-interpret summary measures, as suggested by LeSage and Pace (2009, p. 39). These measures divide the average total effect (ATE) into an average direct effect (ADE) and an average indirect effect. In our context, the ADE is defined as the expected impact on a given manor i’s value when its innate productivity η i is increased by 1. Therefore, it can be interpreted as an average marginal effect of a shock in the latter variable. Alternatively, the ATE is defined as the expected impact on a given manor i’s value when the innate ability of all manors in the sample is increased by 1. The average indirect effect is then defined as the difference between the average total and indirect effect. To facilitate interpretation, the ADE and ATE for every mechanism are reported separately, so that their relative magnitudes can be assessed. These statistics are calculated by putting the coefficient(s) of the other mechanism at 0, which effectively shuts down that channel.

RESULTS

Table 4 presents the estimates for our structural network model, in which the feudal interaction effects are comprised of both the δ and λ parameters. Overall, we find large positive and statistically significant effects for the productivity spillover parameters in all specifications considered. When only one of both networks is included (Columns (1) and (2)), we have that

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_F$

equals 0.79 and

$\hat {\lambda}_F$

equals 0.79 and

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_G$

equals 0.92. In these cases, the feudal and geographic networks capture part of each other’s effect due to their, as previously highlighted, correlated nature. As a consequence, modeling both networks simultaneously (Column (3)) reduces both estimates to 0.38 for

$\hat {\lambda}_G$

equals 0.92. In these cases, the feudal and geographic networks capture part of each other’s effect due to their, as previously highlighted, correlated nature. As a consequence, modeling both networks simultaneously (Column (3)) reduces both estimates to 0.38 for

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_F$

and 0.65 for

$\hat {\lambda}_F$

and 0.65 for

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_G$

. The inclusion of county and soil quality fixed effects (Columns (4), (5), and (6)) absorbs some, but not all of the network effect. The scale spillovers through the geographic network are quite substantial, with estimates for δ G ranging from 0.17 (Column (2)) to as high as 0.44 (Column (3)). However, these scale effects are consistently dominated by the dependence on the unobserved productivity term, as both the ATE and the ADE are larger for the productivity spillovers. As we highlighted earlier in this section, there is more potential for scale spillovers through the geographic network than the feudal network. The estimates for the resources β are comparable to those of the preferred specification (Column (4) in Table 2) in the reduced-form model.

$\hat {\lambda}_G$

. The inclusion of county and soil quality fixed effects (Columns (4), (5), and (6)) absorbs some, but not all of the network effect. The scale spillovers through the geographic network are quite substantial, with estimates for δ G ranging from 0.17 (Column (2)) to as high as 0.44 (Column (3)). However, these scale effects are consistently dominated by the dependence on the unobserved productivity term, as both the ATE and the ADE are larger for the productivity spillovers. As we highlighted earlier in this section, there is more potential for scale spillovers through the geographic network than the feudal network. The estimates for the resources β are comparable to those of the preferred specification (Column (4) in Table 2) in the reduced-form model.

Table 4 ESTIMATES OF THE STRUCTURAL MODEL (GS2SLS)

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Source: Authors’ estimations.

Additionally, in Column (7), we present estimates for a model that contains an interaction effect between the feudal and the geographic network. Such an interaction effect allows for a differential impact of feudal peers depending on their geographic distance to a manor, as it might be reasonable to presume that peers who are neighbors exhibit stronger interaction effects in both networks.Footnote 40 We find a positive and significant interaction effect for the productivity spillover mechanism. However, the effect of scale spillovers is both economically and statistically insignificant.

Our model also allows us to test whether the effects of the feudal network are heterogeneous across different types of manors. Did a manor’s number of feudal peers contribute to the feudal spillover mechanism? And were religious or secular holdings more keen on interacting with their network neighbors? To answer these questions, we estimate a model as in Column (6), but with the inclusion of an interaction of the relevant source of heterogeneity with peers’ average unobserved productivity (for the productivity spillovers) and average value (for the scale spillovers). We find that both effects significantly increase with the size of the feudal neighborhood, although the rise on spillover effects in productivity is the most marked (Figure 4a). This heterogeneity is not unsurprising, given that such manors might had have a higher probability of interacting with the most innovative manors. In addition, we find that manors with religious ownership also experience much higher spillover effects than those with secular ownership (Figure 4b). This can be attributed to two factors. First, the organizational hierarchy of ecclesiastical domains facilitated closer interactions between its manors, encouraging extensive communication among its laborers and managers.Footnote 41 Second, these extraordinary spillover effects can be interpreted within the long-established idea that ecclesiastical domains were forerunners in the adoption of medieval agricultural innovations.Footnote 42

Figure 4 HETEROGENEOUS FEUDAL NETWORK EFFECTS

Source: Authors’ estimations.

Finally, we investigate whether the observed feudal effects are driven by interactions among manors within the same estate, that is, manors possessed by the same lord, or also by spillovers between estates. Certain spillover mechanisms, primarily the possibility of having common ownership structures, can be expected to play a larger role within a single estate. To formalize this, we separate the feudal network into two distinct networks, F W and F B. The former captures connections between manors belonging to the same estate (i.e., network condition (ii)), while the latter captures connections through a common tenant-in-chief or in situations where the tenant-in-chief of one manor is the lord of the other (i.e., network conditions (i) and (iii)), respectively). In an elaborate model, we allow for spillovers through both networks separately. Crucially, the results in Table A5 in the Online Appendix highlight that feudal correlations are not solely driven by economic interactions within a single estate. More specifically, we observe that scale and productivity spillovers play a statistically significant and sizable role through manorial interactions both within and across estates. As a result, the observed interaction effects are not merely the result of common management structures across manors held by the same owner.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

Network Endogeneity

Collusion among powerful nobles striving to obtain the most productive landholdings could explain the feudal clustering of economic activity. This is especially important in the context of King William’s England, as the feudal system under investigation was only put in place 20 years earlier. Such endogeneity concerns are fundamentally inherent to any non-experimental empirical work on interaction effects but are mitigated by the historical origins of the Anglo-Norman feudal institutions. A first argument is that the structure of the feudal system was strongly influenced by non-economic features like military and political considerations. In his “tenurial revolution,” William the Conqueror structurally reshaped the landscape of England to his own vision. Land-holdings with great defensive importance close to the borders or the sea were especially sought after by the landed elite (Fleming 1991, p. 147). A second argument is that the formation of the feudal system, if actually influenced by economic considerations, was likely to be based on easily observable proxies for the value of manors. Although our structural model will not allow for network formation based on unexplained productivity, it does allow for network formation based on resources. That is, even if the newly created feudal system was mainly based on population density and the availability of lands and ploughs, our estimates are still consistent and can be interpreted as actual spillover effects.Footnote 43 Third, we refer to our previous observation of network interactions being significantly larger for ecclesiastical domains in comparison to seignorial manors. Given that the Conquest left the continuity of several church holdings largely unaffected (Dyer 2009, pp. 83–84), this provides further evidence that network endogeneity was not a likely explanation for the observed network effects.

Aside from this historical evidence, we propose two empirical tests to examine the issue of network endogeneity. First, one can leverage the 1066 values in Domesday Book to examine the relationship between a manor’s economic changes over the two decades following the Conquest and its network properties in 1086.Footnote 44 If network endogeneity was the sole driving factor of the observed peer effect, one would expect the powerful elite to obtain lands with high valuation in 1066, and to observe no relationship between ownership characteristics and growth in agricultural performance over the following decades. In contrast, if the aforementioned interaction mechanisms were in play, being part of a productive ownership cluster would induce economic development. To test the presence of such a network treatment effect, we regress the difference in log values between 1066 and 1086 on the average value-to-labor and value-to-capital of peers. The results of this exercise can be found in Table 5. We find that the values of those within better feudal networks (i.e., more efficient peers in 1086) have enjoyed substantially more value growth. This is a strong indication that having productive feudal peers indeed leads to manors thriving in terms of economic prosperity.

Table 5 CHANGE IN VALUES (1066–1086) AND PEER PRODUCTIVITY (OLS)

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1

Source: Authors’ estimations.

Second, we conduct a graphical test for network endogeneity, which is based on the discussion in Boucher and Fortin (2016). In this test, which is detailed in Online Appendix E, a model of network formation is assumed to exhibit homophily.Footnote 45 Given our structural model, when network formation is endogenous, the presence of homophily induces some testable implications for the joint distribution of the residuals of both models. The bivariate kernel density plots suggest that endogeneity, if present, is likely not a substantial issue.

The Obscurities in Domesday Book

Domesday Book presents a unique quantitative insight into an eleventh-century economy. Nevertheless, it remains a complex historical document, created at a time when centrally organized inquiries of the like were unknown. The resulting obscurities, both in structure and content, have been identified as a prime cause for the surprising neglect of Domesday Book by economists (for an up-to-date discussion on the matter, see Walker (2015)). In what follows, we scrutinize how the unresolved uncertainties in Domesday Book are to be interpreted within the context of our findings.Footnote 46 In doing so, we also aim to contribute to the literature by illustrating the upsides and pitfalls of the econometric analysis of Domesday Book, as well as to shed econometric light on some of the debates in Domesday scholarship.

NETWORK MISMEASUREMENT

While Domesday Book is by far the most comprehensive source on a feudal network known to economic historians, it is still crucial to assess whether our results are sensitive to the incomplete identification of Anglo-Norman landowners. The mismeasurement of networks is an ever-present concern in empirical work on peer effects. This is especially relevant in the construction of historical network matrices.

About 85 percent of landowners in Domesday Book are identified with reasonable certainty. It is likely that the remaining manors with unidentified ownership structure are somewhat different in an unobserved nature. The mismeasurement of these inter-manorial connections could, therefore, induce selection bias in our network estimates. As discussed earlier, we consider manors with missing identification on their lordship as having their own idiosyncratic lord. These manors are connected to the network only through their identified tenants-in-chief. To assess the impact of this assumption, we reestimate our interaction models on the extreme premise that among the unidentified lords, those with the same name within a given circuit are in fact identical individuals. Table A6 in the Online Appendix shows that this leaves our results basically unaltered. Moreover, we conducted an additional sensitivity check in which all manors with unidentified ownership were dropped from the sample. This sensitivity check also has very little impact on our results (see Online Appendix Table A7); we may conclude that our estimates are most likely not driven by network mismeasurement.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF DOMESDAY BOOK

Our analysis paid close attention to the disentanglement of feudal and geographic network effects. To achieve this, we relied on the geographic picture of England that is presented in Domesday Book. In the introduction to his seminal study, Darby (1977, p. 13) claims that this picture, “while neither complete nor accurate in all its details, does reflect the main features of the geography of the eleventh century.” The question we ask here is whether these omissions and inaccuracies drive our results in any way.

One such uncertainty lies in the nature of the manorial concept in Domesday Book. In the majority of cases, these holdings were confined to a single location, making up a small community or being part of a larger village. However, Domesday manors were sometimes scattered across several locations. Until now, these manors were omitted from the analysis, as the disentanglement of feudal and regional peer effects can only be made with less certainty. We cannot rule out that this induces a selection effect, as multiple-location manors of the like are typically larger and could differ in their unobservable characteristics. To alleviate such concerns, we devise an alternative strategy in which we assign these manors to the centroid of their respective locations. To avoid assigning senseless locations to manors, we still drop manors for which one of the locations is more than five kilometers from its centroid. Online Appendix Table A8 reveals that the inclusion of these manors has little impact on the estimated parameters of our models.

Another aspect of Domesday geography that deserves special attention is the role of distance. In our baseline analysis, we modeled the interaction with neighboring manors as a function of distance: the further away one’s neighbor, the less strongly that interactions and the subsequent spillover effects occur. The choice of this distance function is contingent on our assumptions with respect to the role of distances, travel, and information in medieval England (for a discussion, see Langdon and Claridge (2011)). Here, we establish that these do not drive our results. In our baseline analysis, we used a double-power distance function with a parameter d equal to 20 km. In Online Appendix Table A9, we evaluate the sensitivity of our models to the choice of d. In particular, we estimate three additional cases, including a low level of d = 10 km and an implausibly high level of d = 100 km. The remarkably consistent estimates of the feudal effects

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_F$

and

$\hat {\lambda}_F$

and

![]() $\hat {\delta}_F$

across all four cases reveal that the choice of the distance function parameter d does not alter our findings, neither in a qualitative nor a quantitative sense. In addition, Online Appendix Table A10 presents estimates where our weighting function is replaced by binary indicators that indicate whether manors are within (band (i)) 0 to 20 km; (band (ii)) 20 to 50 km; or (band (iii)) 50–100 km of each other. From this table, one can see that the effects of the feudal effect are essentially unaltered. More interestingly, the estimates for the geographic effects are small and mostly statistically insignificant for bands (ii) and (iii). This suggests that geographic effects generally did not reach beyond 20 km, or one day’s travel, which further supports the use of d = 20 km in our main specification.

$\hat {\delta}_F$

across all four cases reveal that the choice of the distance function parameter d does not alter our findings, neither in a qualitative nor a quantitative sense. In addition, Online Appendix Table A10 presents estimates where our weighting function is replaced by binary indicators that indicate whether manors are within (band (i)) 0 to 20 km; (band (ii)) 20 to 50 km; or (band (iii)) 50–100 km of each other. From this table, one can see that the effects of the feudal effect are essentially unaltered. More interestingly, the estimates for the geographic effects are small and mostly statistically insignificant for bands (ii) and (iii). This suggests that geographic effects generally did not reach beyond 20 km, or one day’s travel, which further supports the use of d = 20 km in our main specification.

THE MEANING OF DOMESDAY VARIABLES

While the variables in Domesday Book often show great simplicity at first glance, their interpretation is not always as straightforward. The controversial ploughlands variable, which we introduced earlier, is the prime example of this. Despite being typically associated with the statement “land for so many ploughs,” it is uncertain whether this variable effectively measures the amount of arable land available for the manor’s agricultural activities. In our baseline analysis, we took this variable at face value and considered it a control for the amount of land. In Online Appendix Table A11, we repeat our analysis with the ploughlands variable omitted. In other words, we assume perfect complementarity between land, capital, and labor. In doing so, we extend the sample to manors for which no ploughlands are recorded. It is apparent that our findings with respect to the feudal peer effect are robust to the exclusion of the ploughlands variable and to the inclusion of these manors. The estimated coefficients of interest

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_F$

and

$\hat {\lambda}_F$

and

![]() $\hat {\lambda}_G$

are remarkably unchanged. Somewhat unsurprisingly, we observe the biggest impact on the ploughs’ effect.

$\hat {\lambda}_G$

are remarkably unchanged. Somewhat unsurprisingly, we observe the biggest impact on the ploughs’ effect.

Another important discussion is the open debate on Domesday Book’s manorial valuations. Many historians have interpreted these valets (values) as a measure of income, which the landowner derived from his or her manor. Evidence in support of this theory originates in Galbraith (1929), who illustrated how a Domesday manor was rented out at the price of its value. Additionally, the well-researched case of Canterbury presents great consistency in how the ecclesiastical grounds were valued across twelfth-century sources (Du Boulay 1966). Or, as Dyer (1995, p. 198) concludes, “it is on the basis of such evidence that a case can be made for some comparability between Domesday values and annual income deriving from manors in the twelfth and thirteenth century.”

However, it is an open debate as to whether the valets comprise the entire stream of revenue that flows to the manorial lord. Some historians argue that only money rents are accounted for, challenging the generally held view that “Domesday values are a more or less accurate index of the productive capacity of estates” (Roffe 2007, p. 241). This implies that these values are a measure of the peasants’ cash contributions to the lords rather than of the manor’s own agricultural activities.

Such an interpretation would align poorly with another, more quantitative approach to the nature of Domesday values, furthered by McDonald and Snooks (1985). The crux of their argument lies in the close statistical relationship between a manor’s resources and valuation, leaving little room for contributions from the peasant side of the economy.Footnote 47 Additionally, a more recent study finds a much weaker correlation between peasant plough teams and valuations, than between the lord’s ploughs and the latter (Walker 2015). This does not lend credence to the interpretation of values as a cash contribution by the manor’s peasants. Our results on the feudal structure of valuations in Domesday Book add new evidence to this ongoing debate. That is, it is unclear as to why and how agricultural activities of the peasant economy should be interconnected across the feudal system, compared to the management practices of the lords in their seigniorial holdings.

FINAL THOUGHTS

This paper presents the first evidence of the pervasive nature of feudal institutions in the manorial economy. Building on the land ownership data in Domesday Book, we reinterpret and model the feudal system as a network that facilitates economic interactions. Indeed, we find that landowners’ wealth accumulation was closely intertwined with the fortunes of their peers. Manorial values in Domesday England were positively and significantly influenced by both the unobserved value productivity and the absolute value levels of their feudal peers. The former can be explained by inter-manorial knowledge-sharing mechanisms, which were capable of playing a crucial role in a world where agricultural information was scarce. The latter effect is credited to scale spillovers, facilitated by agricultural cooperation across feudal peers. In this process, we empirically establish the presence of economic interactions between manors during the High Middle Ages, which constitutes the first evidence of the role of manorialism in economic integration in that era.

Our paper opens up avenues for future research. To start with, our approach to network formation was heavily inspired by the feudal structure as presented by Domesday Book, allowing us to model the eleventh-century web of ownership structures in a comprehensive manner. Domesday Book is, however, silent on any other network structures that might affect the economic interaction mechanisms described in this paper. For instance, eleventh-century England was a highly multilingual society, composed of many different cultures and languages. It cannot be ruled out that the intensity of interactions across the feudal network was heavily regulated by this polyglot reality. In a similar manner, family relationships, while largely unknown to the historian, could prove relevant. We did not account for such cultural or familial networks, except for the degree to which these relationships are correlated with the feudal structure. More research on the etymological nature of the names in Domesday Book might offer additional insights into the extent to which this was the case.

Further analysis of the underlying economic and social mechanisms is also required. As with all cross-sectional studies based on observational data, it is inherently difficult to isolate the true underlying mechanisms without the help of theoretical arguments and sound judgment. This is especially true for Domesday Book, where only limited and imperfect data is available to researchers. Furthermore, the nature of this source makes it inherently difficult to answer questions on the dynamic effects of feudalism: linking the data in this study to other medieval sources could yield additional insight into the longer-term implications of feudal network connections. Be that as it may, Domesday Book reveals a fascinating insight into the feudal interdependencies within medieval economies.