Introduction

Despite global community efforts to minimize parasitic helminthiases in humans and animals in recent decades, numerous cases of such devastating diseases are still reported worldwide (Carmena & Cardona, Reference Carmena and Cardona2014; Bartsch et al., Reference Bartsch, Hotez, Asti, Zapf, Bottazzi, Diemert and Lee2016; Cucher et al., Reference Cucher, Macchiaroli and Baldi2016; Khademvatan et al., Reference Khademvatan, Salmanzadeh, Foroutan-Rad and Ghomeshi2016; Saki et al., Reference Saki, Khademvatan, Foroutan-Rad and Gharibzadeh2017; Weatherhead et al., Reference Weatherhead, Hotez and Mejia2017). Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato (s.l.), a cestode helminth belonging to the Taeniidae family, is the causative agent of a prevalent zoonotic disease, cystic echinococcosis (CE) (Rojas et al., Reference Rojas, Romig and Lightowlers2014). This tapeworm uses canids and herbivores/omnivores as definitive and intermediate hosts, respectively, and human infection occurs accidentally by ingestion of the eggs (Rokni, Reference Rokni2009). The disease in humans entails the development of a fluid-filled hydatid cyst, which localizes in the liver and lungs and, to a lesser extent, in the abdominal cavity, muscle, heart, bone and nervous system (Craig et al., Reference Craig, McManus and Lightowlers2007). The disease causes impotency, disability and decreased work productivity in endemic territories, including Australia, New Zealand, China, Russia, South America, North Africa and the Middle East (Battelli, Reference Battelli2009; Shariatzadeh et al., Reference Shariatzadeh, Spotin, Gholami, Fallah, Hazratian, Mahami-Oskouei, Montazeri, Moslemzadeh and Shahbazi2015). As a consequence of CE, 1–3.6 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) are missed globally; most of these cases occur in low-income countries (Budke et al., Reference Budke, Deplazes and Torgerson2006; Torgerson et al., Reference Torgerson, Devleesschauwer and Praet2015). Given the numerous traditional animal husbandries and access of dogs to waste materials of abattoirs there, Iran has been considered a hyperendemic region (Dalimi et al., Reference Dalimi, Motamedi, Hosseini, Mohammadian, Malaki, Ghamari and Ghaffarifar2002; Pour et al., Reference Pour, Hosseini and Shayan2011; Khademvatan et al., Reference Khademvatan, Yousefi, Rafiei, Rahdar and Saki2013). More recently, the weighted prevalence of hydatidosis in human and animal intermediate hosts in Iran reached 4.2% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 3.0–5.5%) and 15.6% (95% CI = 14.2–17.1%), respectively. The pooled prevalence of E. granulosus infection in definitive hosts totalled 23.6% (95% CI = 17.6–30.1%) (Khalkhali et al., Reference Khalkhali, Foroutan, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Aryamand, Khezri and Aminpour2017). Human infection in Iran was mostly concentrated in the south, whereas the lowest prevalence rate was observed in central parts of the country (Khalkhali et al., Reference Khalkhali, Foroutan, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Aryamand, Khezri and Aminpour2017). The annual monetary burden of CE in the country was estimated to be c. USD 232.3 million (Mobedi & Dalimi, Reference Mobedi and Dalimi1994; Harandi et al., Reference Harandi, Budke and Rostami2012a).

Extensive intraspecies genetic diversity of CE has been recorded over a long period of time, and this condition may influence characteristics such as morphology, epidemiology, host specificity, infectivity and drug resistance (Carmena & Cardona, Reference Carmena and Cardona2014). Four molecular approaches – single-gene analysis using mitochondrial DNA, microsatellite markers for polymorphic DNA loci, full-genome exploration, and comparison of discrepancies among mitochondrial and nuclear DNA for species hybridization – have been used to categorize Echinococcus species into several genotypes (Ito & Budke, Reference Ito and Budke2017). Most of our understanding in this area originates from the investigation of Bowles and colleagues into cox1 and nad1 mitochondrial genes (Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1992). Accordingly, ten deduced strains of CE have been characterized and encompassed in a number of clades, including E. granulosus sensu stricto (s.s.) (G1–3), E. equinus (G4), E. ortleppi (G5) and E. canadensis (G6–10), and E. felidis (the lion strain) (Amer et al., Reference Amer, Helal, Kamau, Feng and Xiao2015). G1 and G2 are sheep strains, whereas G3 and G5 are buffalo and cattle strains, respectively. G4 is found in horses, G6 in camels, G7 in pigs and G8–10 in cervids (Rojas et al., Reference Rojas, Romig and Lightowlers2014). G1 genotype is the most commonly reported in human CE cases globally. Additionally, studies have reported that the subsequent strains are infective to humans (Grosso et al., Reference Grosso, Gruttadauria, Biondi, Marventano and Mistretta2012). Host–parasite immunological interplay and cross transmission templates can justify the emergence of Echinococcus strains and their related genetic diversity (Bowles et al., Reference Bowles, Blair and McManus1992; Thompson, Reference Thompson2013; Thompson & Jenkins, Reference Thompson and Jenkins2014). Detecting these genetic variations in E. granulosus s.l. populations is significant for better understanding of various life cycles of CE in endemic regions of Iran and shedding light on more efficient prevention strategies, as well as diagnosis and treatment of CE (Shariatzadeh et al., Reference Shariatzadeh, Spotin, Gholami, Fallah, Hazratian, Mahami-Oskouei, Montazeri, Moslemzadeh and Shahbazi2015).

Thus far, numerous papers have investigated CE genotypes in animal hosts and human cases in Iran. However, there is a lack of collective and processed data for systematic review. Accordingly, we performed a qualitative evaluation to clarify the status of CE genotypes in the country.

Methods

Search strategy

To unravel the genetic distribution of hydatid genotypes in Iran, a systematic review was designed on the basis of literature in English and Persian available online. Four English (PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct and ISI Web of Science) and three Persian (Scientific Information Database, Iran Medex and Magiran) databases were explored for published papers from inception to 31 December 2015, as was Google Scholar as a common, multilingual engine for both English and Persian terms. The current review was conducted using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: ‘Echinococcus granulosus’, ‘Echinococcus’, ‘Echinococcosis’, ‘Hydatid’, ‘Hydatic’, ‘Iran’, ‘Prevalence’, ‘Epidemiology’ and ‘Genotype’, alone or combined together with ‘OR’ or/and ‘AND’ operators.

Study selection and data extraction

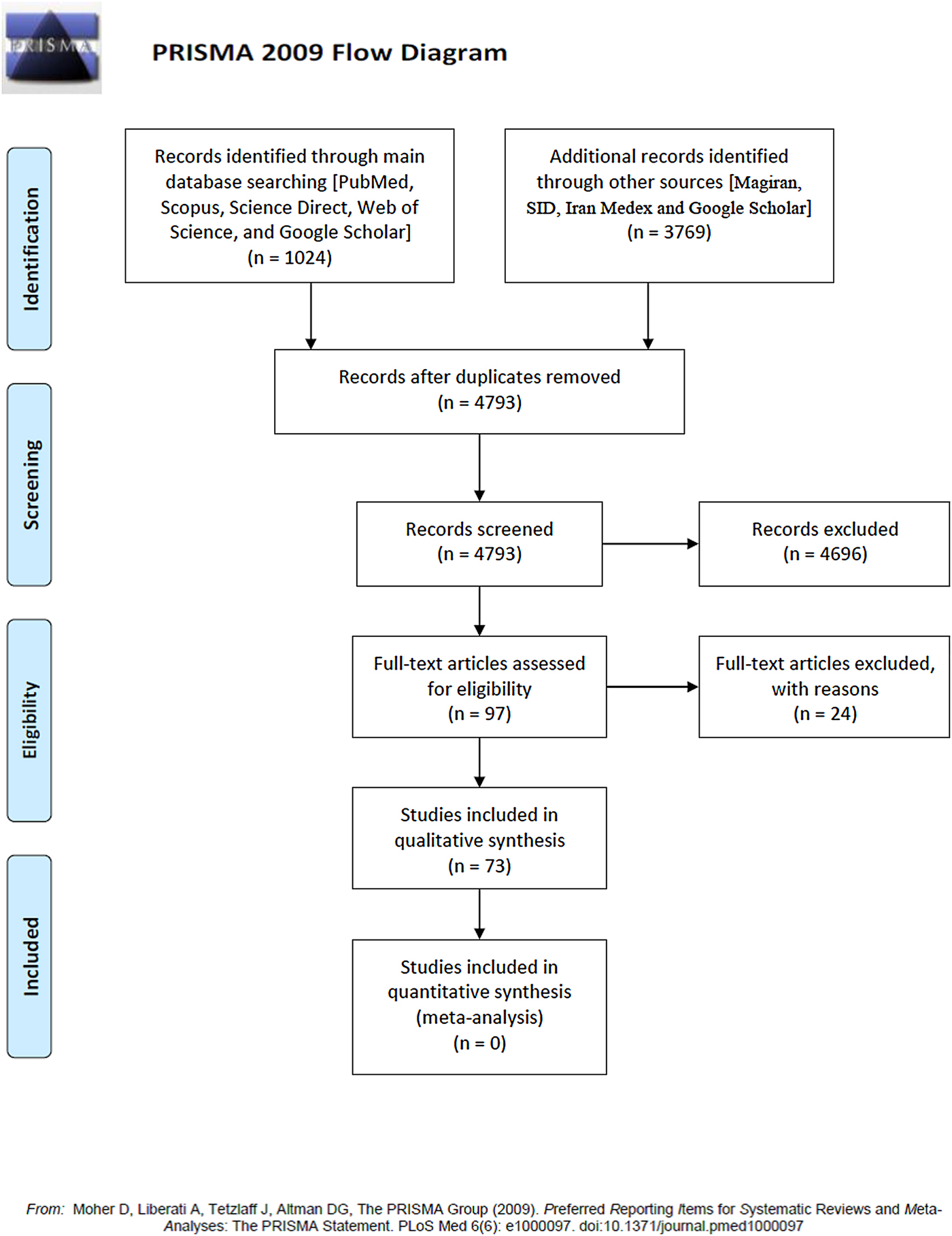

Eligibility of studies and inclusion criteria were checked carefully by two independent reviewers (S. Khademvatan and S. Aryamand). Contradiction among studies was obviated by discussion and consensus (Foroutan-Rad et al., Reference Foroutan-Rad, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Aryamand, Rahim and Malehi2016a, Reference Foroutan-Rad, Majidiani, Dalvand, Daryani, Kooti, Saki, Hedayati-Rad and Ahmadpourb; Majidiani et al., Reference Majidiani, Dalvand, Daryani, de la Luz Galvan-Ramirez and Foroutan-Rad2016; Foroutan et al., Reference Foroutan, Dalvand, Daryani, Ahmadpour, Majidiani, Khademvatan and Abbasi2017a, Reference Foroutan, Dalvand, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Khalkhali, Masoumifard and Shamsaddinb, Reference Foroutan, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Khalkhali, Hedayati-Rad, Khashaveh and Mohammadzadehc; Khademvatan et al., Reference Khademvatan, Foroutan, Hazrati-Tappeh, Dalvand, Khalkhali, Masoumifard and Hedayati-Rad2017; Khalkhali et al., Reference Khalkhali, Foroutan, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Aryamand, Khezri and Aminpour2017; Maleki et al., Reference Maleki, Khorshidi, Gorgipour, Mirzapour, Majidiani and Foroutan2017). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer-reviewed original research papers; (2) cross-sectional studies based on various polymerase chain reaction techniques and investigating the genotypes of E. granulosus in Iran; (3) published in English or Persian; (4) published online from inception to 31 December 2015; (5) full-text articles were available. Papers that failed to meet these criteria were excluded. The required data were collected accurately using a data extraction form, on the basis of the first author, province, geographical region (north, south, east, west, centre), infected organ, genotypes (G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, G6, G7, G8, G9, G10), intermediate and definitive hosts, human cases, type of diagnostic method and the DNA/RNA fragment used in detection. The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2010). ArcGIS (http://www.esri.com) was used for mapping the geographical distribution of various genotypes of E. granulosus in Iran.

Results

In total, 73 of 4793 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review (fig. 1). Literature search results and study properties (species, genotypes, animal intermediate host, definitive host, number of animal and human cases) are presented in table 1. Table 2 and supplementary fig. S1 show the geographical diversification of genotypes detected in different provinces in Iran. The number of each genotype in each of the various hosts is shown in table 3.

Fig. 1. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1. Genotypes of Echinococcus granulosus identified in domestic natural hosts (intermediate and definitive) and humans in Iran.

Table 2. Numbers of E. granulosus s.l. genotypes identified in various regions of Iran.

Table 3. Numbers of E. granulosus s.l. genotypes identified in animal and human hosts in Iran.

Intermediate and definitive animal hosts

In total, 2952 animal (intermediate and definitive) hosts were examined for cystic echinococcosis. Five E. granulosus s.l. genotypes exist in Iran (G1, G2, G3, G6, G7), and five livestock species (sheep, goats, cattle, buffaloes, camels) were affected by CE (table 1). With the exception of G7, which is localized in Khorasan province, eastern Iran, other genotypes were detected mostly in central and western parts of the country (supplementary fig. S1). Molecular studies revealed that E. granulosus s.s. clade (G1–3) was involved in most cases of infection, among which the G1 genotype was the most diverse and prevalent, with 2738 of 3058 (92%) cases in animal hosts, and dominant in 17 provinces, particularly in West Azerbaijan (table 2). The geographical distribution and involvement of various intermediate hosts demonstrates why G1 is the most abundant in the country. Results also revealed that the dog–sheep cycle of CE is widespread in most parts of Iran, indicating that G1 is viable for transmission. Most G3 and G6 cases were reported from Isfahan and Fars provinces, respectively (table 2). Animal host involvements of each recognized genotype in Iran are as follows: G1 (92.75%) and G6 (4.53%) in sheep, cattle, camels, goats and buffaloes; G3 (2.43%) in five herbivore hosts and dogs; G2 (0.06%) in dogs; and G7 (0.2%) in sheep and goats (table 3). In one study, genotype co-infection with G1, G3 and G6 was discerned. With respect to G2 and G7 genotypes, more sequencing data from various animal hosts (intermediate and definitive), particularly from provinces with fewer studies, are required to reach a rational consensus on the host range and geographical distribution of these genotypes. The findings suggest that special attention be paid to water buffaloes in subsequent works, as they may play a role in lifecycle maintenance of G1, G3 and G6 strains in Iran. Some characteristics of the G6 genotype are significant for CE diagnosis and control strategies (Kamenetzky et al., Reference Kamenetzky, Muzulin, Gutierrez, Angel, Zaha, Guarnera and Rosenzvit2005; Chow et al., Reference Chow, Gauci, Vural, Jenkins, Heath, Rosenzvit, Harandi and Lightowlers2008; Muzulin et al., Reference Muzulin, Kamenetzky, Gutierrez, Guarnera and Rosenzvit2008). No sequencing information exists for the G4 genotype in Iran, necessitating molecular studies in horses. No molecular evidence from G8–10 genotypes has been reported from the country.

In general, in the case of neighbouring countries there was a low diversity in the animal hosts examined and subsequently in CE genotypes isolated, with most studies focused on E. granulosus s.s. (Utuk et al., Reference Utuk, Simsek, Koroglu and McManus2008; Latif et al., Reference Latif, Tanveer, Maqbool, Siddiqi, Kyaw-Tanner and Traub2010; Simsek et al., Reference Simsek, Balkaya, Ciftci and Utuk2011; Eryıldız & Şakru, Reference Eryıldız and Şakru2012; Hama et al., Reference Hama, Mero and Jubrael2012; Hama & Shareef, Reference Hama and Shareef2016; Hasan et al., Reference Hasan, Fadhil and Fadhil2016; Gökpınar et al., Reference Gökpınar, Değİrmencİ and Yıldız2017; Hassan et al., Reference Hassan, Mero, Casulli, Interisano and Boufana2017). With some exceptions (Al-Qaoud et al., Reference Al-Qaoud, Abdel-Hafez and Craig2003; Trachsel et al., Reference Trachsel, Deplazes and Mathis2007; Ziadinov et al., Reference Ziadinov, Mathis, Trachsel, Rysmukhambetova, Abdyjaparov, Kuttubaev, Deplazes and Torgerson2008), the strains identified in definitive hosts in Iran are partly identical to detected genotypes in adjacent countries.

Human cases

In total, 340 cases of CE in humans have been reported, with sequencing data, from Iran. Major E. granulosus genotypes in infected individuals include G1 (n = 320) and G3 (n = 7) as E. granulosus s.s., and G6 (n = 13) as E. canadensis (tables 1 and 3). Alongside the exclusive G1 genotype, which is dominant globally, G6 is the most prevalent clade in human infections in Iran, similar to recent data from South American countries (Cucher et al., Reference Cucher, Macchiaroli and Baldi2016). Based on the study of Sadjjadi et al. (Reference Sadjjadi, Mikaeili, Karamian, Maraghi, Sadjjadi, Shariat-Torbaghan and Kia2013) in Iran, E. canadensis is responsible for brain infections, suggesting an alternative predilection site to the liver. Consequently, nationwide research is required to clarify the exact epidemiological status and biological behaviour of this clade in Iran. Based on our results, the highest and lowest incidences of human CE infections were in Isfahan (168 cases) and Kerman (two cases) provinces, respectively. Considering the capability of cattle and camels to harbour multiple genotypes (table 1), these animals probably play a central role in preserving the CE life cycle and the risk of human transmission, particularly camels in central arid parts of Iran, where they are possibly involved in G6 environmental maintenance. The absence of G7 (pig strain) in human cases may be partially attributed to the lack of pig breeding in Islamic culture. Human cases in Afghanistan and Pakistan have been discerned as the G1 strain, whereas more diverse CE genotypes have been isolated from human subjects in Iraq and Turkey than in Iran (Rojas et al., Reference Rojas, Romig and Lightowlers2014).

Discussion

Cystic echinococcosis is an important neglected parasitic disease worldwide. In a review of the current situation of echinococcosis in Asia, Ito & Budke (Reference Ito and Budke2017) discussed various aspects of CE throughout the continent but provided no data for Iran. The current work and a previously published meta-analysis (Khalkhali et al., Reference Khalkhali, Foroutan, Khademvatan, Majidiani, Aryamand, Khezri and Aminpour2017) appropriately report up-to-date information regarding the epidemiology of CE in Iran. Several strains of CE with specific epidemiological and biological emphases have been categorized in various clades, including the following: E. granulosus s.s. (G1–3), E. equinus (G4), E. ortleppi (G5) and E. canadensis (G6–10), and E. felidis (the lion strain). More studies using sophisticated molecular tools are a requisite to revealing more genotype diversity and their respective hosts in Iran. This paper reviewed works featuring sequencing discrimination of CE genotypes in natural hosts and human cases in Iran. Reportedly, G6 was the second most abundant genotype in all hosts, after G1. Regarding antigenic variations in EG95-related proteins of G1 and G6, studies should focus on the diagnosis, chemotherapy and pathogenicity of the G6 strain (Alvarez Rojas et al., Reference Alvarez Rojas, Gauci and Lightowlers2013). The lack of human cases of the G4 genotype may be attributable to the requirement of additional host samples and sequencing information and/or the non-infectious condition of the G4 genotype for human hosts. A wide range of animals were proven to be involved in the ecological maintenance of pastoral and sylvatic life cycles of CE. Our review was confined to published literature, and therefore our findings may not provide a full representation of CE genotypes throughout Iran. In conclusion, the data obtained from this systematic review could benefit local and nationwide CE control initiatives, such as effective CE vaccines for dogs and livestock, improved diagnostic methods for humans and definitive hosts, efficient treatment options and development of well-structured mathematical models for better evaluation of cost-effective interventions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X18000275

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all staff of the Department of Medical Parasitology of Urmia University of Medical Sciences and Tarbiat Modares University, Iran.

Financial support

This study received financial support from the Student Research Committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran (grant no. 1395-01-42-2621).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran (IR.UMSU.REC.1395.511).

Author contributions

S. Khademvatan and M. Foroutan conceived the study; S. Khademvatan and S. Aryamand designed the study protocol; M. Foroutan and S. Khademvatan searched the literatures; S. Aryamand extracted the data; H. Khalkhali analysed and interpreted the data; H. Majidiani wrote the manuscript; S. Khademvatan, H. Majidiani, M. Foroutan and K. Hazrati Tappeh critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.