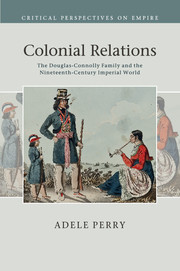

This book uses the story of one family to analyze the vernacular history of the imperial world over what historians call the long nineteenth century. It tracks the histories of James Douglas (1803–1877), his wife, Amelia Connolly (1812–1890), their kin, and peers in the eastern Caribbean, the United Kingdom, and various parts of North America, including the British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia where Douglas would serve as governor. The story of what I call the Douglas-Connolly family (see Figure 1.1) is a complicated and at times disjointed and oblique one. Part of this story is well known to historians of Canada, and more particularly British Columbia. The story of these colonial relations is less well known to historians of empire, but their history is salutary for historians committed to critically engaging with imperialism's complicated and consequential past. This history makes clear the power and the possibility of thinking beyond accustomed definitions of empire and nation, and demonstrates the potential of re-reading empire through a critical feminist lens that connects the presumed jurisdictions of the private and the public.

Figure 1.1 Douglas-Connolly family tree.

I return to these points in the conclusion. I begin where historians like to, which is with the archives. In the past decade historians have explored the records produced and left by the colonial states as particular, racialized, and gendered forms of technology. In different ways, Anne Laura Stoler, Antoinette Burton, Durba Ghosh, Anjali Androkar, Julia Emberley, and Betty Joseph urge us to see archives as a terrain of colonial histories rather than simply as a source of them. Colonial archives are a technology that helped produce the world rather than a window into it.1

My analysis of the Douglas-Connolly family and the lived history of empire is based on a critical ethnographic conversation with the colonial archives. The footnotes that follow enumerate sources that are familiar to historians of imperialism, the eastern Caribbean, and western North America: the records of the British colonies of Demerara and Essequibo, Vancouver Island, and British Columbia, the papers created by the administration of slavery and abolition, the records of private fur-trade companies, especially the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), the correspondence of missionaries and reformers, metropolitan and colonial newspapers, published travel literature and memories, a range of personal and family archives including letters and journals, and materials gathered by local historians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. These records are held in the archives and libraries of postcolonial Canada and Guyana, in repositories in the United States and the United Kingdom, and in the distinctly translocal space of the internet.

All of these archives are profoundly shaped by the individuals who created them, the state and private enterprises they labored on behalf of, and by the people, institutions, and societies that preserved them. These archives are multiple, scattered, and episodic. They impose a discipline on the historian who works with them. Social historians and historians of women and the colonial world have long been accustomed to reading archives “against the grain.” Here I try what Stoler calls “reading along the archival grain,” treating colonial archives “both as a corps of writing and as a force field that animates political energies and expertise, that pulls on some ‘social facts' and converts them into qualified knowledge, that attends to some ways of knowing while repelling and refusing others.”2

I begin with the probable time and place of James Douglas' birth, early nineteenth-century Demerara. In the 1970s and '80s, historian Charlotte Girard combed the archives of Guyana, Barbados, Canada, the Netherlands, and Great Britain for data about James Douglas' early life. She found little direct evidence, but was able to skillfully link fragments of records to produce a tentative and cautious identification of his probable mother and grandmother.3 I have found nothing that definitively proves Girard's argument and nothing that either challenges it or provides a plausible alternative. The uncertainty about Douglas' origins is part of the history analyzed here rather than a simple impediment to it. The babies born in nineteenth-century colonial societies were a complicated problem for empire, one that was in part managed by practices of non-recognition. As Ghosh explains in her study of the family in colonial India, the archive “serviced the imperatives of the government by erasing or excluding various subjects,” including “native mistresses, out-of-wedlock children, and multiple families.”4

The colonial state in early nineteenth-century Demerara recorded ordinary people in the greatest detail when they bought property, sold property, or themselves became property through practices of slavery. I know most about Douglas' probable mother and grandmother when colonial governments regulated, taxed, or compensated them for their slaveholdings. Whatever relationships or children they or people like them had did not provoke the same kind of archival attention. British Guiana took no censuses until 1839, and there was no system of registering births until the 1860s.5 Only a few sets of baptismal records have survived, and Georgetown's newspaper didn't report early nineteenth-century births beyond an episodic accounting of the numbers of unnamed “free coloured” and “White” boys and girls born in a given month.6

The personal archive does not supply all the information absent from the records kept by the state. A list of important events that Douglas kept reflected his own uncertainty about his history. “1803 June 6 Borne?” he asked himself.7 As an adult Douglas was notoriously tight-lipped about his own background. A son-in-law recalled that “personal experiences were not much talked about.”8 In 1923, one of Douglas' granddaughters asked her mother about his history. Her response was a sketchy list:

1. His mother was a Miss Ritchie.

2. Born in Lanarkshire.

3. His Father owned sugar Estates in Demerara.

4. Judge Cameron was only married once, to my Aunt, Cecilia Douglas – (she was married twice. R.B.)9

As either the sum total of what a daughter knew about her father or what she chose to tell her own daughter, this was scanty, unstable, and at least somewhat untrue. As in the Ngai Tahu communities of southern New Zealand studied by historian Angela Wanhalla, “stories circulated, myths abounded,” and “ancestry was shadowy.”10

All of this makes it difficult to write a standard biography of Douglas and, for not dissimilar reasons, Connolly Douglas. She was born in Cree territory in what is now northwestern Canada in 1812, and it was only an unexpected court case and some family records that put details about her parents' marriage and her birth into the colonial archive. Colonial lives like those of Douglas and Connolly Douglas force us to recalibrate our default settings for biographical research. Historian Clare Anderson has recently reminded us that we can and should tell the stories of plebeian colonial people's lives, however fragmentary our versions of them must be.11 The necessity of working with partial and vexed archives closes down some interpretative avenues, but it opens others up. Joseph argues that “Reconciling oneself to a partial history is ultimately a call for producing a new kind of narrative.”12 While this book utilizes the analytic frame of the individual life and the family, it is not a conclusive genealogy or conventional biography. Instead, I utilize available archival evidence about one extended family to anchor an analysis of the nineteenth-century imperial world, to ground and focus these wide, wandering, and sometimes daunting histories.

Douglas entered the colonial archive as an unmistakable biographical subject when, in 1819, he became an unfree laborer in North America's fur trade. He surfaced occasionally in the records kept by the North West Company and more often in the records of the HBC, in the direct employ of which he would remain for more than three decades and with which he and two of his sons-in-law would remain associated for their working lives. The HBC archives are an enormous and often fastidious record of furs secured, trade goods exchanged, provisions needed, and workers and workplaces managed. Douglas became a routine presence in these records when he was appointed to a position of authority in the 1830s. From 1839 to 1858, he was the leading authority of the HBC on the Pacific coast and, as a result, a constant and formative presence in the records it left. Douglas became governor of the British colony of Vancouver Island in 1851 and of the colony of British Columbia in 1858, and in these capacities was the most powerful local representative of the British imperial state on North America's west coast. He remained as such until his retirement in 1863/4. As chief factor and governor, he was central to the making of two enormous archives of empire, and I can make no claims to comprehensive knowledge of them.

The records of the HBC and the colonial governments were mainly produced in colonial space, but with the interests and concerns of the metropole always in mind. And it was there that these records were gathered, sorted, and archived. Over the course of the twentieth century, the records of British North American colonies and the fur trade were increasingly claimed as part of the domain of Canadian history and relocated, literally as well as figuratively, from the space of the empire to the space of the nation. In the early twentieth century, Canada's national archive acquired copies, first in transcript and photostat and later in microform, of the Colonial Office records relating to British administration of northern North America. In 1974 the Hudson's Bay Company Archive was patriated to the Archives of Manitoba, a maneuver registered as a return of a national treasure.13 Historians' interests made a similar sort of journey, becoming increasingly engaged with narratives of nation and region, and less engaged with imperial or oceanic frames. This book is part of a wider scholarship that aims to reconnect histories of Canada and the territories that preceded it with a critical historiography of empire.14

The range of authors, interests, genres, and administrative regimes at play here make clear that this is not a single colonial “archive,” but a polyvocal set of archives. The subjects included or excluded from these archives reflect their different priorities, interests, and optics. The records of the HBC and British colonial governments are full of men, figured as curiously separate from their lives as sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers. As an author, subject, audience, and authority, Douglas is everywhere in the archives of the HBC and of the colonial governments of Vancouver Island and British Columbia. But Douglas as a person with a history and a family is mainly absent from the formal letters, despatches, and reports. It is not that kinship and intimacy were irrelevant to this or other institutions of empire. Relations between Douglas and the male in-laws with whom he worked throughout his adult life – first his father-in-law in the HBC, then two sons-in-law in the HBC and colonial government, and finally two more sons-in-law in Vancouver Island and British Columbia's colonial governments – were key to this local colonial state. Intimate relations between male kin run subcutaneous throughout the history of the nineteenth-century empire, obscured by patriarchal naming practices that disassociated male kin from one another. These ties were not unnoticed by critics of British North American states, who deemed the colonial governments run by Douglas and other tightly knit local elites as those of the “family compact.”15 Here, I try to excavate the connections between kin and the endurance of women's connections to the families of their birth. Whenever possible I follow the practice of a number of members of the Douglas-Connolly family and use women's surnames of birth alongside their married names in an effort to trace the complicated ties that bound men and women to one another and helped to structure local states and the nineteenth-century British Empire as an aggregate.

The colonial archives imagine men in specific ways and figure women at best infrequently and in ways that obscure their histories. As Burton has argued, the official archive is gendered from the start, associated with male authority and textual records, and disassociated from women, speech, and fiction.16 The gendered schism of record-keeping calcified in the North American colonial contexts when primarily oral Indigenous cultures met primarily textual European ones in charged and uneven ways. As in colonial India, Indigenous women are often tellingly nameless in fur-trade records, described only by a first name or an association with a place or a man.17Amelia Connolly Douglas was the daughter of one powerful man in the fur trade and then the wife of another, but her presence in the fur-trade archive was never much more than uncertain. But women and children sometimes surface in the records that desired and, at the same time, helped to constitute their presence as both tangential and unknowable. The rich historical scholarship on women and the fur trade that I draw on throughout this book would not be possible otherwise. Here, I too use the information about women found scattered throughout the fur-trade archive to piece together information about Amelia Connolly Douglas, her female kin, and the women they lived alongside. The records left by Connolly Douglas' sister, two of the family's daughters, and other female friends and kin help us situate elite colonial women within the imperial world and some of the local spaces remade within it. But this remains an archive where men speak with greater frequency, detail, and volume than do women.

I do not and cannot adequately restore Amelia Connolly Douglas to the story told here. She was recognized as the chief factor's and then the governor's wife and shared in whatever honorifics her husband accrued. Her small role in the local imperial public sphere was codified in an official archive that only rarely admitted her presence. The family's daughters were more regular participants in the public performance of empire in Vancouver Island's capital city of Victoria, and their intimate relationships and social connections were closely observed by settlers and passers-by alike. The colonial archive produced under Douglas' early administration was in part created in space that was both the family home and office of state. In the 1850s, the family's eldest daughters both assisted their father with the paperwork of governance, and Jane was recalled as Douglas' “amanuensis.” This is a different iteration of the complicated politics of gender, kinship, and authorship in the nineteenth-century imperial world traced by historian Zoë Laidlaw.18

This pattern of voluble husbands, quiet daughters, and quieter wives reflects hierarchies and schisms between orality and literacy as well as between men and women. My methodology reflects a discipline forged in the sinews of empire and nation and predicated on the colonial state's production and maintenance of the archive and the privileging of alphabetic texts. The extent to which histories of Indigenous North American societies that communicated, honed, and preserved knowledge primarily through oral and material means can be adequately addressed through this sort of lens is an enduring question worth asking again and again.19 We might also ask whether presuming the absolute difference of Indigenous and European societies' forms of archives reifies difference and occludes the range of archival practices in both Indigenous and settler societies in nineteenth-century North America. The written archive left by settler society is far from seamless or representative. Indigenous peoples also left written archives, and this study makes use of the correspondence and memoirs created by English-speaking, Indigenous elites like Marguerite Connolly, Andrew Dominique Pambrum, Ranald MacDonald, and Cecilia Douglas Helmcken. How to describe people like these has been and continues to be a complicated question in Canada, as it is in many colonial and postcolonial societies.20 Moving between the eastern Caribbean and northern North America, I used the terms Metis and Creole to describe people born in colonial space and tied to both local and imperial genealogies and economies. This is admittedly an imperfect way of capturing histories that were complicated in their time and remain consequential in the present.

It was after Douglas left the colonial service in 1864 that he created a significant archive of his intimate life. This reflects his attainment of secure bourgeois status, and in this sense, the association between written records, worthy and interesting stories, and class. The journals and letters Douglas wrote as an older man are not lists of furs traded and servants employed, or correspondence between different and distant levels of an imperial state, but personal documents: journals, memoirs, and the vivid and at times disarmingly intimate letters of fathers, daughters, and sons. Here the danger of becoming what Jill Lepore memorably dubs “a historian who loves too much”21 is a real one. So is the risk of taking such material as more representative than it is even within the frame of one life. Douglas' private archive was overwhelmingly created in the 1860s and '70s, when he was an older, relatively wealthy man with unparalleled local influence and ample time. We cannot read the relations and subjectivities mapped in these archives backwards in time. But alongside the large and eclectic collection of papers of Douglas' son-in-law James Sebastian Helmcken and the less voluminous but still revealing diary of his other son-in-law, Arthur T. Bushby, Douglas' correspondence and journals offer a remarkable window into colonial masculinity, elite Creole-Metis life, and bourgeois domesticity. Correspondence exchanged between family members in North America and the United Kingdom later in the nineteenth century documents a different layer of bourgeois colonial life, as do the records produced by the administration of the family's estate in the twentieth century.

All of these archives reflected the societies that produced them and the ones that preserved them or were unable or uninterested in doing so. In 1888 Nicholas Darnell Davis, a colonial official and local man of letters in British Guiana, voiced the familiar cri de coeur of colonial peoples unable to access their own archives and write their own histories: “‘Our records! Where are they?'”22Guyana's national archives were established in 1958. They did not fare well in the complicated and fractious years that preceded and followed Guyanese independence in 1966. In 2008, the archives were renamed the Walter Rodney National Archives after the socialist Guyanese historian assassinated in 1980. And there I read church and census records under a stern and magisterial portrait of the slain Rodney, a reminder that the work of history is always political and sometimes very dangerous. The Walter Rodney National Archives continue to inspire criticism and both local and international reform plans.23 The history of Guyana's archives cannot be separated from its status as one of the poorest countries in the western hemisphere. The Guyanese histories mapped in this book are prised from an underfunded archive in a radically unequal world.

The archives and historiographies of Canada's westernmost province have had different colonial and postcolonial histories. British Columbia became a relatively secure settler society in the last decades of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth century. Catherine Hall explains the critical role that capital H history played in justifying Britain's sense of itself as a justly imperial nation. History performed a different but not unrelated work in British Columbia, situating it within an imperial world and justifying the dominance of settler peoples within it. The professionalization of history in Canada, as Donald Wright has argued, rested in part on the exclusion of women. Mary Jane Logan McCallum has also shown how this process of professionalization was additionally predicated on the denial of authority to Indigenous scholars and writers, something that echoes uncomfortably throughout contemporary scholarly practice. These processes of professionalization dovetailed with a local history of archive and historiography building. Historian Chad Reimer has shown how the intellectual work of settler colonialism was served by a group of elite British Columbians who established a provincial archive and a local historiography with claims to professional rigor in the last decade of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century. In this sense, the creation of a local archive and historiography was critical to the location of British Columbia within what Australian historians Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds have called the “White Men's Countries” of the modern world.24

The acquisition of James Douglas' records and the celebration of his histories were central to the making of an archive and a capital H history for British Columbia. In 1923 James Douglas and Amelia Connolly Douglas' youngest child, Martha Harris Douglas, gave the Provincial Archives of British Columbia a pamphlet of addresses made to Douglas on his retirement and an odd assortment of material tokens: the trimming from Douglas' “first dress Uniform,” the sash from the duffle coat he wore as HBC chief factor, and a button from his dress uniform. The archivist was deferential and grateful in response. “Needless to say,” John Hosie gushed, “we treasure these possessions very much and they make a very interesting addition to the exhibition case which we have specially reserved for documents and relics of your esteemed father, Sir James Douglas.”25

This sort of recognition reflected the secure space Douglas occupied within the aspirational historiography of regional settler colonialism. Soon after his death in 1877, he was proclaimed a “father” of British Columbia, and he held fast to that status, the namesake of schools and the subject of plaques, paintings, and commemorations. A granite obelisk erected in front of British Columbia's legislative buildings in 1881 and pictured in Figure 1.2 speaks to Douglas' assigned role in modern reckonings of British Columbia as a settler society.26 As a fur trader, colonial governor, proverbial self-made man, and a brave pioneer, he fit nicely within expected ideas of what was a legitimate subject of local history. The first book-length biography of Douglas was published in 1908, and they continued to appear at regular intervals throughout much of the twentieth century.27

Figure 1.2 The monument to Sir James Douglas, British Columbia Legislature, Victoria, BC.

But the Douglas-Connolly family could not be easily accommodated within triumphalist settler narratives. Douglas vexed his biographers. They struggled with the apparent absence of solid information about his early life. Soon after Douglas' death, Hubert Howe Bancroft, the famed historian of western America, expressed his surprise that there was so little archival material “concerning the early career of such a man.”28 Twenty years later, a local historian found it peculiar that “the first governor of the province and a citizen of great worth, leaving the impress of his individuality, his superior talents and public-spirited citizenship upon the annals of the northwest,” had such an unknown early life.29 The questions of where Douglas had been born and who his mother was were especially troubling, carrying with them the capacity to disrupt and destabilize ideals of race and of nation, and Douglas', and thus British Columbia's, place therein. Some authors avoided the question of where he had been born altogether, offering general musings about his Scottish lineage instead of the usual biographical information. Douglas' first scholarly biographer, Walter Sage, stated that Douglas had been born in Scotland.30 This claim reflected how troubled Sage was by the possibility of Douglas being Black. In his research notes, Sage noted a report that Douglas' mother was “Creole” and dismissed it, writing “rot” in the margins. Sage's emphatic kind of abjection did not make him any less confused, and years later he would admit that Douglas was a hard subject to write a plaque about. “The real difficulty is, of course, the date and place of Douglas' birth,” Sage explained in 1946.31

Douglas' family of birth strained available discourses of North American history, and so did the family he made with Connolly Douglas. Canadian historians could draw on romantic, longstanding narratives of the fur trade and its unique, historic, and picturesque ways. These were less available to those writing in an American idiom. Bancroft spent time in Victoria in 1878 and reported that Connolly Douglas, “though a half-breed, was a perfect lady” and her daughters charming. This he credited to Douglas, writing that “it was next to impossible for the wife and daughter of Sir James Douglas to be other than ladies.”32 Elsewhere Bancroft explained the genuine disquiet he felt at the unavoidable fact that Douglas and his peers had married Indigenous women and, worse, had Indigenous children. In his major 1884 work on the history of western America, Bancroft wrote:

I could never understand how men such as John McLoughlin, James Douglas, Ogden, Finlayson, Work, Tolmie, and the rest could endure the thought of having their name and honors descend to a degenerate posterity. Surely they were possessed of sufficient intelligence to know that by giving their children Indian or half-breed mothers, their own old Scotch, Irish, or English blood would be greatly debased, and hence that they were doing all concerned a great wrong.33

For Bancroft, fur traders' intimate lives made them unworthy and disturbing objects of historical study. Bancroft's celebratory histories of the North American west would find a place for the British colonies, but were never certain about where to place men like Douglas within them.

Popular historians of British Columbia struggled with where to situate Connolly Douglas in their stories of place. She received mention in studies of her husband or in portraits of women's history, most enduringly in ephemeral terms that re-inscribed her status as an unknown and somehow outside history.34 Sometimes, she was very much present, as when the Victoria branch of the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire, Canada's pro-empire women's group, dubbed themselves the Lady Douglas chapter. Connolly Douglas merited a full chapter in a 1928 book on “pioneer women of Vancouver Island.” This made no clear mention of her Indigenous history, but was in effect all about just that, recollecting her childhood among “the picturesque figures of the first fur traders, the Canadian voyageurs, the Indian trappers, the proud chiefs.”35

It has been more recent histories that have emphasized Connolly Douglas' and Douglas' itinerant histories and complicated identities. The Guyanese-Canadian community has found Douglas a historical antecedent to the countless Guyanese who, since the 1960s, have migrated to the global north in general and Canada in particular. They have also worked to have him acknowledged as a historical figure in Guyana, and the handsome statue erected in Mahaica in 2008 and shown in Figure 1.3 is a clear sign of this.36 Novelist Jane Pullinger uses Douglas and Connolly Douglas' story as a historical reference point for a fictional reckoning of the complicated pulls of race and sexuality in the postcolonial present.37 At least two scholars have seen the Douglas-Connolly family as one of a set of families based at Fort Vancouver who well illustrate the complicated ties of nation, race, and identity in nineteenth-century North America. Historian Sylvia Van Kirk analyzed Douglas and Connolly Douglas in her critical 1980 study, and returned to the rich fabric of their lives in her later work on fur-trade elites in Victoria.38

Figure 1.3 Statue of James Douglas, Mahaica, Guyana, 2010.

Here I argue that the Douglas-Connolly family's wide-ranging and mobile histories are best registered in wide-angle and over the longue durée. I wrest the family, and more particularly Douglas, from the locations where they have been most understood and valued and draw out their histories in the Caribbean, the United Kingdom, in parts of North America that were later territorialized as American, and parts of North America that later became Canada. The first half of this book traces the Douglas-Connolly family in Demerara, Rupert's Land, and Oregon Territory. The last half analyzes the family mainly in British Columbia, but emphasizes their ongoing connections to a wider imperial world. This sort of approach is often dubbed a transnational one, and my analysis here is transnational in that it rejects the presumption that the modern nation-state is the best or most natural container of history. But the lives examined in this book were mainly lived in colonies, places that emphatically and by definition lacked the rights that defined nations. For this reason these histories might be better described as transimperial or, borrowing Arjun Appadurai's frame, translocal.39

Empire was global, but it played out in local spaces with thick and enduring histories. In early twentieth-century Victoria, Martha Douglas Harris was the most prominent local representative of what was a storied and celebrated family with diminished resources and prospects. Douglas Harris embraced the role of family representative even when it pushed at the limits of respectable middle-class womanhood. She used the surname of her birth alongside her married name, making clear that she remained a Douglas. Douglas Harris could also complicate the kind of racial performance that was so critical to her family and other members of the fur-trade elite. She shared her knowledge with Nellie de Bertrand Lugrin, wife of Victoria's newspaper editor and author of women's history.40 She also worked to assert and maintain control over her family's archive and the histories tied to it. She met with Sage twice in 1923 and made her objection to his biographical research on her father unmistakably clear. “Mrs. Harris says that most of what has been written about the early life of her father is hopelessly wrong. But she is none too willing to part with the facts. She says that she has them,” Sage recorded in his notes.41

Douglas Harris was furious when she learned that the provincial archives had allowed Sage to see some of her father's records. In 1931 she wrote a stern letter explaining that she had placed “valuable papers” in the library during the Great War under lock and key, retrieved them when she learned “that my father's letters to me had been read,” but accidentally left Douglas' confidential report on colonial staff. “W. Sage had no right to see it or use that paper,” she charged. Along with other members of Victoria's fur-trade elite, Douglas Harris was no fan of Bancroft, and she was horrified that Sage referenced the work of a man she considered a “thief & a liar.” As the provincial librarian and archivist, Hosie recognized Harris Douglas' authority over the archive and the histories that might be found therein. He returned her documents with ready and fulsome apologies. “I deeply regret the whole incident,” he explained, agreeing that Bancroft had “robbed at least three of our old time families of priceless documents.”42

It was after Douglas Harris' death that her father's private records – his letters to children at school in England, his accounts of books read and money saved, his fragmentary mentions of early life, his accounts of journey and travels – were decisively moved to British Columbia's archives.43 In comparison to the available archives through which we might learn about Douglas' or Connolly Douglas' early life and the enormous institutional archives of the HBC and the Colonial Office, these records are rich, compelling, and detailed. But like the other sources mined in this study, these private records archives are still partial, fragmentary; a product of the imperial world that made them and the changed one that preserved them.

The colonial archive that makes this history of the Douglas-Connolly family and the history of the imperial world possible also occludes the knowledge a critical feminist and postcolonial scholarship seeks. The available records are weighted toward one member of the family, one location in their itinerant geography, and select aspects of their lives. This archive renders Indigenous histories at best poorly visible by treating written records as the only ones worth valuing, putting in boxes, and making available by card catalogue or search engine. A settler archive committed to a politics of Whiteness skips over or literally crosses out archival traces of a Black and, in different ways, Indigenous past. The colonial archive occludes women's histories by failing to see or value their labors, concerns, or centrality to their families and communities. It truncates the complexity and meaning of men's lives by registering their paid labor, their trade, and the relationships to states and showing much less interest in their lives as friends, husbands, and fathers. The archive is spread across multiple locations, ones that reflect distinctions between the global north and south, the national and regional mandate of archives, and the happenstance of people who made choices about what to keep and what to burn.

Taking the Douglas-Connolly family as its spine, this book is organized along topical and chronological lines. It reverses the presumed order of precedence between public and private and state and society, and begins, in each instance, with the intimate terrains of marriage, kinship, and family. The analysis starts with the imperial intimacies of early nineteenth-century Demerara and fur-trade North America before turning to the complicated histories of colonial rule and race in those places and at those times. The center of the book analyzes fur-trade North America in the middle decades of the nineteenth-century, addressing the vexed history of marriage and intimacy before turning to questions of colonial economy, race, and empire. The focus on James Douglas, Amelia Connolly Douglas, and their children sharpens over the course of the book. The final three chapters examine their lives in Vancouver Island and British Columbia, beginning with the politics of marriage before turning to governance, race, and nation in their lives and the lives of their children. It concludes by connecting the intimate histories of Douglas and Connolly Douglas' children and some of their grandchildren to questions of class, race, and nation in the modern world.

I want a history that speaks critically to the complicated present of postcolonial and settler colonial societies, to the many shattered spaces of empire. I want a history that engages meaningfully with the relentlessly gendered history of colonialism and how it has and continues to determine the fabric of our lives – Indigenous, settler, or migrant – and animate the kinds of possible futures we image and the kind of relationships we establish or fail to establish with each other and the spaces where we live. I cannot pull this kind of history whole from the colonial archive. But I can work with these records to create a history that connects people, places, and lives, and in doing so shifts our view of the imperial world and the local spaces remade by it. The Douglas-Connolly family lived in the tissues of empire, moving between the Caribbean, the United Kingdom, and northern North America. They were colonized and colonizing, White, colored, and Black, British, Scottish, and native-born, Indigenous and settler, and Roman Catholic and Protestant. They spoke English, French, Chinook Jargon, Cree, and Michif, and probably some Dutch.

But the history told here is not a story of cheerful pluralism and timeless multiculturalism, about how we were all happy then. It is a history of slavery and the racism that remained after abolition and the exploitation of the fur trade. It is very much a history of colonial rule, national states, and imperial administration. At its very core it is a history of Indigenous dispossession and settler ascendancy. This is a history of colonies and metropoles, of new nations, reworked empires, and enduring Indigenous peoples and governance. Yet this is also a history of people and their lives. The history of the Douglas-Connolly family is of women and men, wives and husbands, daughters and sons, old friends and people passing through, ties maintained and bonds misplaced and lost, sometimes temporarily and sometimes forever. This is a story about class and material relations, especially as they were lived out in local colonial spaces, ones that were hardly legible on the metropolitan stage. It is a story of local history with complex histories, and also an imperial and global one of disjointed connection and movement. Putting these colonial relations at the center of our analysis changes how we see the imperial world and the places and peoples remade by it.