Introduction

Muslims have been present in the region from the very beginnings of the consolidation of political power hereFootnote 1 – first by the Asante, who coalesced into the AsantemanFootnote 2 at the turn of the eighteenth century, followed by British colonialists, and then the Ghanaian nation state after independence. Predominantly migrant traders or labourers, Muslims integrated as ɔhɔhoɔ (strangers) into the local context. As such, they were largely ‘free to do our own’, as my interlocutors put it, but this freedom shifted with historical changes. The following is a history of Muslim presence in Asante, but this community, its historical trajectory, and the Islamic conceptions, practices, and imaginaries found within it are far from confined to this context. What was first a community of a few Dioula from the north-west changed significantly under colonial rule. The number of immigrant Muslims increased substantially as new traders arrived from the north-east, mainly Hausa and Fulani. They moved into the region after the collapse of the Asanteman and founded the wards that have become known as zongos (it is not by accident that their name derives from Hausa). However, they did not invent Islam anew but integrated the previous Muslim communities with their religious conceptions, practices, and imaginaries, including the manufacture of amulets or funeral prayers, into their emerging community. Hence, Islam in the zongos predates the actual formation of these wards.

Furthermore, there never existed such a thing as a ‘zongo Islam’: in these wards, various Islamic groups were struggling for, maintaining, or loosening religious hegemony – that is, intellectual, moral, and cultural leadership (cf. Gramsci Reference Gramsci and Forgacs2000 [1988]: 194, 249) in Islamic matters. The once prevalent ‘Suwarian tradition’, which apparently shaped Islam in the region during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Wilks Reference Wilks and Goody1968; Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2000; Reference Wilks2011; Wilks, Hunwick, and Sey Reference Wilks, Hunwick, Sey and Hunwick2003)Footnote 3 and has left traces across West Africa (Sanneh Reference Sanneh1997: 37, 214; Ware Reference Ware2014: 87–90), is no longer a major Islamic tradition today. In the late nineteenth century, the Sufi ṭarīqa (path) of the Qadiriyya, an Islamic order with roots in thirteenth-century Baghdad (Robinson Reference Robinson2004: 18–20; Stewart Reference Stewart1976: 90–1; Vikor Reference Vikor, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 443–9), emerged as an ascendant Sufi order in Asante. This group’s early twentieth-century competitors and successors, the Tijaniyya, another Sufi ṭarīqa, trace their roots to an Algerian Islamic scholar who founded the order in the late eighteenth century in Morocco (Abun-Nasr Reference Abun-Nasr1965). Tracing their major influences to the contemporary Arabian Peninsula and Egypt, the Sunna emerged in the zongos during the 1970s as Islamic reformers (Dumbe Reference Dumbe2013; Kobo Reference Kobo2009; Reference Kobo2012). The divergent Islamic conceptions, practices, and imaginaries in the zongos cannot be considered without reference to this history. Nonetheless, the historical trajectory of Muslim presence in Asante is anything but teleological: that is, it is neither oriented towards nor explainable by its actual outcome (Castoriadis Reference Castoriadis1975: 21–82, esp. 81–2; Cooper Reference Cooper2000), nor is it linear. This is a history ‘with many twists and turns’ (to borrow this apt phrase from John Hanson (Reference Hanson2017: 3)), variegated demarcations, and multiple entanglements, not a straight course. As different groups and actors have been vying for and, at times, holding religious hegemony among their fellow Muslims, these have left divergent traces in current Islamic notions, practices, and imaginaries. The complex diversity of Islam in the zongos derives from and is part of this history, in and out of which Islam emerges as both contested and a common ground.

The following is thus a history of Muslim presence in Asante, as I trace the major historical developments and try to come to terms with the varied teleologies implied in the narrations of my interlocutors. Writing this history, I draw on several sources. The archival records I refer to are stored in the Public Records and Archives Administration Department (PRAAD) of the Ashanti Region in Kumase. In addition to these records, I draw on secondary literature and reports in the Ghanaian media. I treat these sources as complementary to what provided me with the basic outline of this chapter, its periodisation, and the historical trajectory it follows: the oral histories of the people of the zongo. I have tried to stick closely to the main themes and periodisation of their ‘communicative memory’ (Assmann Reference Assmann2005 [1992]). Furthermore, I point out where their narrations diverge and how this relates to the historically evolved positionality of the narrators. Methodologically, I draw on ‘Writing histories of contemporary Africa’,Footnote 4 in which Stephen Ellis suggests that the so-called radio trottoir (pavement radio) and its oral histories are a prime source for writing social histories (Ellis Reference Ellis2002: 21). This radio and the histories conveyed by it are ‘the product of a social attempt to organize reality’ (Ellis Reference Ellis2002: 22). The people narrate their histories, agree, argue, or debate, and thereby form a ‘communicative memory’ that is contained within their conversations, addresses, sermons, myths, and remembrances. These do not add up to a single, unanimous account, nor do they necessarily share the same ‘facts’. A central aspect of these oral histories is that their narrators participate in ‘the constant struggle to determine what is fact and what it means’ (Ellis Reference Ellis2002: 24). The histories narrated by my interlocutors diverge in what they present or acknowledge as factual events, how they account for these, and what they consider to be central. Accordingly, I have collected several versions of apparently similar events and crosschecked the narrations with each other and the available sources, not to establish what ‘really happened’ but to grasp the senses my interlocutors made of these events.

Dealing with these oral histories, I face several limitations. The first problematic emerged during fieldwork: in the zongos, the narration of history is a prerogative of the local authorities. It is by narrating history that one lays claim to or legitimises the current state of affairs, which is why this narration is, at times, ardently contested.Footnote 5 As a result, ‘ordinary’ Muslims frequently claimed to lack any knowledge of the history of Islam in Asante and referred me to Islamic scholars. The following is therefore largely founded on histories narrated by male Islamic scholars. Another problematic is the (precise) dating of those events that were commonly classified as akye (‘that is long ago’). The dating that I propose therefore derives from secondary literature and is oriented towards benchmark dates in the history of the region. Another problematic is the possibility of crosschecking. One limitation was set by the claims of my Tijaniyya interlocutors to narrate only their own historical trajectory. When I enquired about events or developments among the Sunna, they referred me to Sunna malams. Similarly, my Sunna interlocutors referred me to Tijaniyya malams for Tijaniyya history. The details of historical developments and contestations among the Tijaniyya are thus derived from narrations of Tijaniyya interlocutors, while those of Sunna history come from Sunna interlocutors. Furthermore, history and its narration are a contested matter within these groups as well. The Tijaniyya are divided into the Cisseyfoɔ (the followers of Cissé) and the Jallofoɔ (the followers of Jallo), and the adherents of these wings evaluate the same events or persons and their impact on their history differently. The Sunna are also swayed by different trends, stressing or downplaying the same events or individuals in disparate ways. As implied in the quote from Ellis, they struggle over what historical events consist of and actually mean. A last methodological problem in writing this history from oral sources is the range of this oral history and the impacts that its narrations have had on it: hegemonic discourses impose their order and labels on the histories they relate (Foucault Reference Foucault1966). The Tijaniyya emerged as hegemonic in the mid-twentieth century, and this has left deep traces in their communicative history. My interlocutors, Tijaniyya and Sunna alike, frequently glossed the Islamic conceptions, practices, and imaginaries of their ancestors as ‘Tijaniyya’. Developments and trajectories that occurred before the emergence of this hegemony were narrated as myths or stories (nsɛm) and not as history (abakɔsɛm). Furthermore, numerous Islamic conceptions, practices, and imaginaries that were apparently present before the establishment of this group were subsumed under ‘Tijaniyya’, despite members of this order having integrated previous Islamic tenets and practices into theirs. Thus, in the oral history of Islam narrated in the zongos, the more than 200 years of Muslim presence before the Tijaniyya were frequently glossed over as ‘Tijaniyya’. In the sections of this chapter that deal with pre-Tijaniyya history, I therefore rely on archival sources and secondary literature rather than on the rudimentary glimpses of this history contained in the narrations of my interlocutors.

I begin this history with the Asanteman (c.1700–1874), although Muslim presence in the region likely predates the consolidation of this dominion. Muslims found in the Asanteman largely stemmed from the north-western Mande areas in the Sahel and lived as traders in close contact with the ‘traditional’ rulers. This began to change in the nineteenth century when Muslim traders from the north-east moved into the region and when the Asante were conquered by British colonisers. The foundation of zongos in the region occurred during the colonial period (1874–1957). Along with the consolidation of the zongos in the 1920s came the emergence of the Tijaniyya. Over the course of one generation, the Tijaniyya gained Islamic hegemony in these wards and supplanted the formerly predominant Qadiriyya. They acquired hegemony in the years that led to Ghana’s independence, in the wake of which the people of the zongo became national ‘aliens’. What was previously kept under the lid of colonial rule, which considered all Africans as colonial subjects, now emerged as a central issue in the forming of the Ghanaian nation state (1957–today): the question of national identity and citizenship. The resulting shakiness of the (legal) status of the people of the zongo, together with the xenophobia they faced, found its apex in the expulsion of them in their hundreds of thousands in the early 1970s. The gain in momentum of the reformist Sunna and their contestations of the Tijaniyya fall within this period. These developments and the (re)actions of the Tijaniyya are described in the last section of this chapter.

The ‘northern factor’: Muslim presence in the Asanteman, c.1700–1874

The Asanteman emerged as a political unit in around 1700 when several groups coalesced against the Denkyira (McCaskie Reference McCaskie2007a), who had been dominant up to then. Until 1874, when they were defeated militarily by British troops, the Asante held and expanded political power in the region.Footnote 6 Muslims from the northern regions had been present within the Asanteman from its very beginnings, and their impact on this oman and its rulers, with whom they closely interacted, has aptly been designated by Ivor Wilks as the ‘northern factor’ (Reference Wilks1961a; Reference Wilks1961b) in the region’s history. In the Asanteman, Muslims acted as scribes and counsellors, diplomats, traders and soldiers, diviners and healers, or ‘slaves’.Footnote 7

When I asked about the history of Islam in the region, the people of Kokote Zongo referred me to Malam Hussain, who narrated the following origin myth about the Muslim presence in Asante:

In the beginnings of the Asanteman, roughly 300 years ago, the Asantehene was waging war against the Kwahu. He had just recently won independence from Denkyira; his reign was young and his ‘kingdom’ small. As this was an opponent of equal size and forces, the outcome was far from certain. Therefore, the Asantehene searched for spiritual assistance to assure victory for him and his troops. To find out who could provide the desired support, he devised a test for the ‘spiritual men’ who came to offer their services. He let his servants wall a black cow into a chamber and then called for these men one by one. To check their ‘spiritual powers’, he had them deploy their spiritual techniques to divine the contents of the chamber. Many of the ‘traditional’ bosomfoɔ and ɔkɔmfoɔ (priests possessed by or serving deities or spirits) failed their divination and were sacrificed to the gods. Then, Nkramo Seifi Hamidu, a Muslim scholar from Wenchi (a town to the north), divined that there was a white cow with a black tail sealed inside the chamber. The Asantehene wanted to sacrifice him to the gods as well, as his divination was quite close but only partially right. However, Seifi Hamidu convinced him to have his servants open the chamber, and his divination proved right as they found a white cow with a black tail inside. The Asantehene was thereby convinced of his great spiritual powers and made him his first spiritual guide and help. He gave him land and wives to settle close to his palace, and he had him pray to Allah and manufacture aduro (cures) and lāyā (charms, amulets) to grant his troops victory in the upcoming battle. By the grace of Seifi Hamidu’s spiritual support, the Asante achieved a great victory against the Kwahu, which laid a cornerstone for their reign in the region, which was to last for the next 300 years. Since then, Muslim scholars have been in close contact with the Asantehene, praying every Friday for him and the Asanteman, manufacturing aduro or lāyā, and providing spiritual services in any matter. This is how Muslims have established themselves as indispensable in the region, where they have been present from the very beginning of the Asanteman.

Hussain was not alone in relating this myth; several Tijaniyya and nkramo malamsFootnote 8 provided me with slightly different versions, the central elements remaining stable. This myth is loaded with significances, and I suggest two perspectives with which to approach it.

The first seeks to ascertain who tells such histories and why. This myth contains a specific outlook on Islam, its practices, and scholars that is not shared equally by all people of the zongo. In fact, many elements of this myth, including divination and the manufacture of charms, are highly contested. Like any narration, this one not only contains certain ideas but is also narrated as an argument in ongoing Islamic discourses. Several malams used this myth to root themselves and their practices in the history of Muslim presence in the region. Other malams, especially the Sunna, who ardently campaign against these practices, cited it only to indicate how lost their ancestors were and what kind of objectionable practices they were engaged in. Hussain is well aware of this. After relating this myth, he pointed out that other malams would tell me different things, and that I had done well to come to him to get ‘the true’. These myths are also value statements, as they contain claims on how things have been, are, and should be. For example, the statement that a malam succeeded where the ‘traditional’ priests had failed is a judgement on their respective spiritual powers, and it clearly differentiates between those who are ‘traditional’ and others who are Muslim.

This myth contains several historical facts that are corroborated in the literature, and, in turn, it corroborates details in the literature. Muslims have been present in the region at least from the late seventeenth century. But, as remarked by Nehemia Levtzion, this was more a spread of Muslims than of Islam, and conversion rates among the Asante remained insignificant (Levtzion Reference Levtzion1968: xxv). These Muslims came from the north as captives of war, Islamic scholars, or traders under the tutelage of the Asante royals (Owusu-Ansah Reference Owusu-Ansah1991; Wilks Reference Wilks1989 [1975]). Their communities could be quite large, but they were kept in check by local rulers, and their interactions with the locals, especially intermarriages, were quite limited. Hence, the Muslim communities in the Asanteman were more or less on their own and were involved in neither proselytisation nor political affairs.Footnote 9 Accordingly, they have not assimilated into the Asante (or the other way round). Wilks has described this stance of Muslims’ non-involvement in local affairs and their refraining from proselytisation as ‘Suwarian tradition’ (cf. Launay Reference Launay2004 [1992]: 78–81; Loimeier Reference Loimeier2013: 105–7; Sanneh Reference Sanneh1997: 214; Wilks Reference Wilks and Goody1968: 177–81; Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 96–8; Reference Wilks2011; Wilks, Hunwick, and Sey Reference Wilks, Hunwick, Sey and Hunwick2003). This tradition goes back to al-Hajj Salim Suwari, a Soninke, who lived in the Sahel in the sixteenth century.Footnote 10 As the name of this scholar ranks prominently in numerous silsila (initiation lines) that Wilks and his assistants have collected in the region, his seems to have been the prominent teaching among Muslims in the Asanteman.

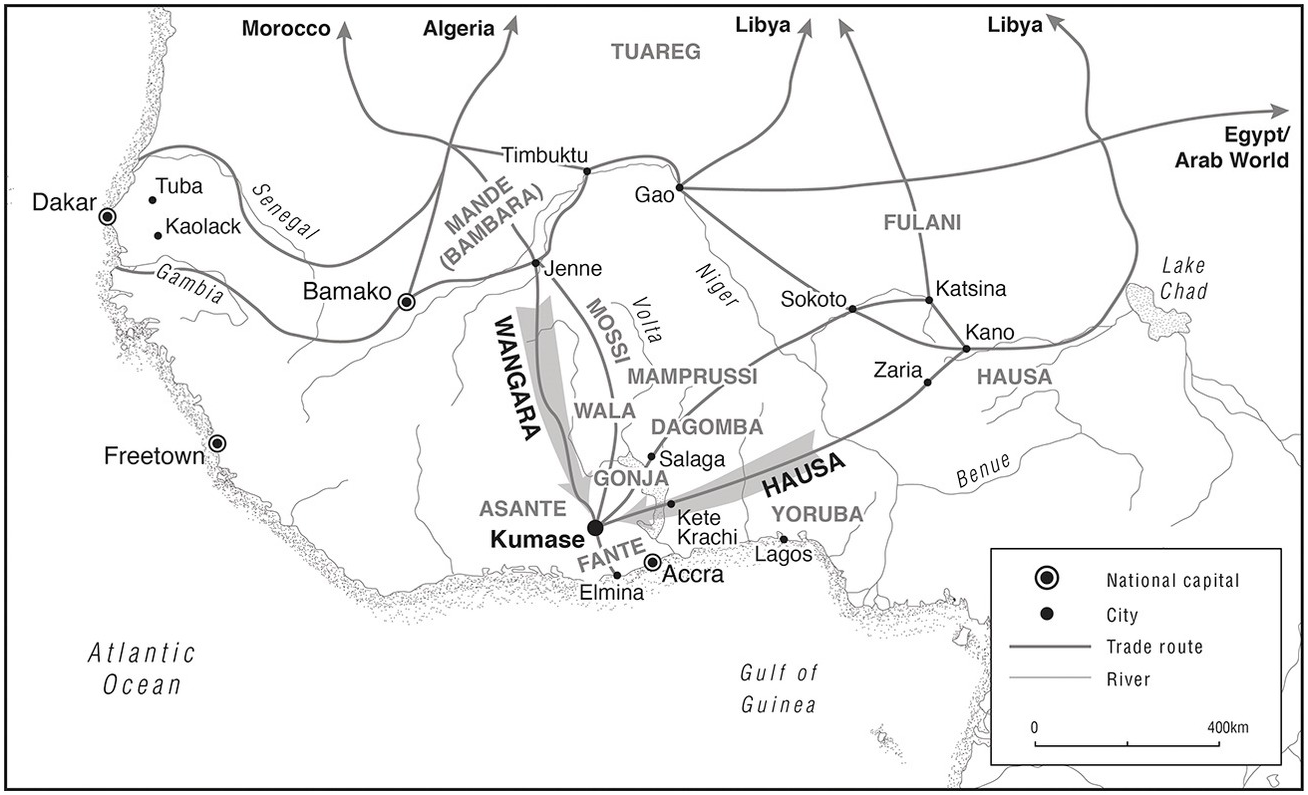

Islamic scholars held a central position in these communities. The designation for Muslims in Asante Twi, ‘nkramo’, derives from the Mande karamɔgɔ (teacher, scholar).Footnote 11 These scholars not only acted as teachers, religious specialists, and (moral) authorities within their groups; their works and advice were also requested by the Asante, especially by the rulers, for whom they worked as scribes and diplomats.Footnote 12 Sometimes, they were close to the ahenfoɔ (‘chiefs’), having a say in their politics; at other times, they were supplanted by other influence groups (McCaskie Reference McCaskie1995; Wilks Reference Wilks and Lewis1966; Reference Wilks1989 [1975]). Furthermore, the malams manufactured aduro as healing or a remedy for any kind of affliction. Their knowledge and prayers were frequently requested by Muslims and Asante alike, and they were renowned locally for their ‘spiritual powers’ (Owusu-Ansah Reference Owusu-Ansah1991; Reference Owusu-Ansah, Levtzion and Pouwels2000; Rattray Reference Rattray1927: 20–1; Wilks Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2000). However, the Muslim communities in the Asanteman did not consist solely of scholars; a large proportion were traders and their aides. They brought in salt, cattle, and slaves from the northern regions, sending back gold and kola nuts (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980; Wilks Reference Wilks1961a; Reference Wilks1961b). These itinerant traders came to sell their goods and to buy others in the local markets, many of which had been founded by them, before they returned to their regions of origin. A major trading route went from the Asanteman to the north-west, passing through Wa.

As Wilks has noted, the Wangara or Dioula (Mande for trader) ‘defy easy identification’ (Wilks Reference Wilks, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 93; cf. Goody Reference Goody, Vansina, Mauny and Thomas1964; Launay and Miran Reference Launay and Miran2000). Today, this designation has attained ethnic connotations as the Wangara or Dioula are perceived and present themselves as an ethnic group, but originally they were far from homogeneous. They included people from various origins; some of them came from as far as Timbuktu, while others were from north-western Côte d’Ivoire.Footnote 13 The traits that marked them as a group included their common language (Mande), their shared religion (Islam), and the fact that they intermarried freely (as Muslims). As a group, the Wangara emerged from their history as itinerant traders; their trading networks connected the Sahara desert to the western tip of Africa and the forests of Asante. The Wangara are thus as much a ‘product’ of their long-distance trade as the group conducting it. These traders were among the first Muslims in Asante, and their religious conceptions, practices, and imaginaries have left traces in those found in the zongos today. Yet, they were not the only Muslims in the Asanteman. There is a numerically larger group that has nonetheless been obliterated in oral histories: ‘slaves’ and captives of war who were gathered in separate settlements and who produced foodstuffs or raw materials (especially gold) for the Asante royals. They were ascribed the social status of akua or ɔdɔnkɔ (slave) and placed under the control of the local ‘chiefs’ (McCaskie Reference McCaskie1995: 95–101; Wilks Reference Wilks1993). This group of people has left barely any trace, as they were largely illiterate and as there was – and continues to be – a strong taboo on speaking about one’s social status or origins as a ‘slave’ in Asante (Agyekum Reference Agyekum2010: 122–3; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1970: 253–4). Nevertheless, their religious imaginaries and practices must have flown into local traditions and histories of Islam as well.

Unfortunately, we have only very limited knowledge about the doctrinal or theological differences and debates that occupied Muslims in the Asanteman. Muslim presence in the Asanteman was neither stable nor unchanging, and Asante was not a stable unit either. Considerable parts of the Muslim communities were ‘on the move’, travelling back and forth between Asante and their regions of origin, and new people and ideas were constantly arriving. But we know very little of the history of these communities, and the first major break in this history that we are currently aware of is the displacement of the Wangara as the predominant group by incoming Hausa during the nineteenth century.

In the early nineteenth century, Usman dan Fodio and his followers waged what has become known as the ‘Fulani war’ in what is now northern Nigeria (Loimeier Reference Loimeier2013: 116–19; Robinson Reference Robinson, Levtzion and Pouwels2000: 137–9; Reference Robinson2004: 139–52). From 1804 to 1808, they fought for the rule of the Hausa states and established the Sokoto Caliphate, which was to endure until its divestiture by the British in 1903. Dan Fodio and his successors enforced ‘sharīʿa law’, which resulted in a growing abstinence from alcohol among the populace.Footnote 14 This culminated in a steep rise in the demand for kola, a small nut that grows on trees in the tropical rainforests and is commonly used as a stimulant ‘social drug’ or as a gift at social events, especially marriages. The nut is broken into small pieces, chewed, and the saliva dissolves a small amount of the stimulant/narcotic substances, whose effects are comparable to coffee, khat, or other ‘social drugs’ (Abaka Reference Abaka2005: 6). As the Sokoto Caliphate was located in the savannah, kola could not be produced locally, and so Hausa traders built vast trading networks to the forests of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana, where the supply of kola could meet their demands (Abaka Reference Abaka and Falola2003; Reference Abaka2005; Arhin Reference Arhin1979; Cohen Reference Cohen1966; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980; Wilks Reference Wilks1962).

The Asante monopolised the harvest of and trade in this cash crop (Abaka Reference Abaka2005; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980: 17), and many Asante planted kola trees to generate additional income besides their subsistence farming (Abaka Reference Abaka2005). Within the Asanteman, kola was collected by local rulers and transported to the northern borders, where it was sold to traders from the Sahel (Abaka Reference Abaka2005; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980). This led to the emergence of several zangō (caravan trading place) markets on the northern borders. The towns of Yendi, Kete Krachi, and Salaga thus evolved into ‘ports of trade’ (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1963; cf. Curtin Reference Curtin1984) where the number of Muslims far surpassed the local population (Abaka Reference Abaka2005; Arhin Reference Arhin1979; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980). Salaga, which emerged as a major market in the nineteenth century, was populated by more than 40,000 people and visited by hundreds of traders per day (Abaka Reference Abaka2005: 79–80; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980: 113).Footnote 15

These trading caravans were social microcosms on the move and could contain several thousand people (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980: 101–6). Through their size and number, they fundamentally changed the Muslim presence in Asante and led to a reorientation of foreign trade in the Asanteman. The Hausa emerged as the largest and most well-funded group, but they remained one group among others. They gained predominance in the zongos, their language became the lingua franca of this trade and its networks, and their Islamic scholars became the main religious authorities (Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980: 39–42; Winchester Reference Winchester1976: 21). The arrival of these Hausa caravans thus also changed Islam in Asante. The Qadiriyya was the predominant order in these networks during the nineteenth century: the major Islamic scholars aligned themselves with this order (Hanson and al-Munir Gibrill Reference Hanson and al-Munir Gibrill2016; Kobo Reference Kobo2009: 506; Levtzion Reference Levtzion, Levtzion and Fisher1986: 13–14; Mumuni Reference Mumuni and Weiss2002: 143). However, their influence merely trickled into Asante, as these traders and Islamic scholars were not free to move into the Asanteman.

To the south, where European traders and colonisers had settled on the coast since the early fifteenth century, the British and their allies waged several wars against the Asante. In 1874, foreign troops entered and destroyed Kumase, the capital of the Asanteman, for the first time in Asante’s history. The Asante failed to recover from this resounding defeat. Internal dissent and rivalries further weakened the already waning rule of the Asantehene, and the Asanteman was conquered and occupied by the British in 1896. The colonisers abolished Asante rule and forced Prempeh I, the Asantehene, into exile, from which he was to return in 1926. Yet, on the ground, the situation was far more complex than the word ‘abolish’ suggests, and the turbulent events of the period are open to speculation. A history of the colonial occupation of Asante is yet to be written (McCaskie Reference McCaskie1986a; Wilks Reference Wilks1996),Footnote 16 but the collapse of the Asanteman surely resulted in the loss of Asante sovereignty and territoriality, ending the closure of the northern borders and the monopolisation of trade. This led to a ‘kola rush’ as the traders moved to the sources of supply, and, within a short period of time, they founded zongos all over Asante.

Unfortunately, we know very little about Islam during that period. There is no study of this history, and my interlocutors either lacked any deeper knowledge of the then current teachings or labelled them erroneously as ‘Tijaniyya’. The main Islamic scholars at the time affiliated themselves with the Qadiriyya and the Qadiriyya wird (litany) was in wide use (Hanson and al-Munir Gibrill Reference Hanson and al-Munir Gibrill2016; Kobo Reference Kobo2009: 506; Rouch Reference Rouch1956: 145; Stewart Reference Stewart1965: 17, 33), but our knowledge about the Qadiriyya presence and influence in the region during the early twentieth century remains limited. According to Charles Stewart, many of the leading malams who taught in the main makarantā (Qur’an schools) and led others in prayer at that time were affiliated to this order – certainly through their lines of initiation (silsila) – and spread its wird. Accordingly, the Qadiriyya must have been influential on lived Islam in the zongos at that time, although it seems that only a minority of Muslims were explicitly members or adhered to their tenets and practices (Stewart Reference Stewart1965). Meanwhile, the Tijaniyya were also gaining a foothold in the zongos and they coexisted with the Qadiriyya for quite a while before they eventually outgrew them in popularity and supplanted them in the early 1950s.Footnote 17

Muslim presence under colonial rule and towards independence, 1874–1957

The colonial period saw the foundation of zongos in Asante over the span of one generation after the breakdown of the Asanteman. The Hausa were not the sole group, as people from across the Sahel and the northern savannahs moved to Asante seeking out sources of livelihood. The Wangara remained present but were outnumbered; Mossi from Upper Volta (part of French Sudan, which became Burkina Faso after independence), Dagomba, Gonja, Mamprussi, and Wala from the northern territories, Zabarama and Kotokoli from Togo or Benin, and Fulani from the Sahel were other major groups to settle in the zongos. From the time of their establishment, these were multi-ethnic and multilingual wards.Footnote 18 However, the main direction of trade and its major means were controlled by the Hausa, who emerged as the predominant group in the early twentieth century although they remained a minority numerically (Winchester Reference Winchester1976: 21).

The colonial institutions considered and governed the people of the zongo as colonial subjects. In the archival sources, they are classified as ‘Muhammadans’ involved in long-distance trade and attempting to bypass colonial control and taxes. Furthermore, these communities were considered apart from the Asante as they adhered to their own traditions and values. Common formulations in colonial correspondence include ‘the Muhamadu native custom’ and ‘the Muslim community observes certain laws and customs peculiar to a minority group’.Footnote 19

Under colonial rule, the numbers of migrants into Asante increased significantly (Kobo Reference Kobo2009: 507; Reference Kobo2012: 71–2; Rouch Reference Rouch1956: 24–6). People from the northern territories moved in to trade or to work in local mines and on farms during the dry season. These were predominantly young men who did not come to stay; at least originally, they came to earn enough for a dowry, or preferably a little more, and then returned north (Hill Reference Hill1966; Peil Reference Peil1971; Reference Peil1974; Rouch Reference Rouch1956: 103; Reference Rouch and Southall1961). This was also the original plan of Maigida, a Mossi from Burkina Faso, who is now in his late eighties and a respected elder of Kokote Zongo:

Maigida made his first trip to Asante in the late 1930s, helping one of his uncles in the kola trade. They did the entire journey from Burkina Faso on foot with their cattle, donkeys, and some porters carrying goods on their heads. This was a walk of roughly six weeks. They headed for Offinso, sold their cattle and cloth, reinvested the profits in kola, and returned to Burkina. Depending on the length of the prize negotiations, the supply of the desired quality of kola, and the duration of the loading, their stays in Offinso could last several weeks. Thus, they took this journey about two or three times a year.

When he reached adulthood, Maigida decided to stay in Offinso and to seek employment as a farm worker for the Asante. He had several employers who hired him for weeding or harvesting and thereby gained a little money. After two years of this kind of work, he deemed his funds sufficient for his dowry and the establishment of a household in his town of origin. He bought as much kola as he could transport and returned to Burkina, where he got married. However, things did not turn out as expected, and he could not establish himself and his household in his community. Therefore, he returned to Offinso where he established himself as a maigidā (‘houseowner’ or ‘landlord’ – a middleman in the long-distance trade) and settled down once and for all. He spent the major part of his life in Offinso as a middleman in the kola trade, the activity from which he got his name, and working as a watchman at the local college. Although he never rose to the status of maigidā titire (main middleman), he lived quite well from his work and achieved a certain wealth, which allowed him to cater (temporarily) for three wives and several children. Today, he is a widely respected elder (ɔpaanin) in Kokote Zongo, although his fortunes have diminished as much as the number of his wives – only one of whom remains. His children have mostly left Offinso, and he makes a living as a scrap dealer and with a little trade in kola.

Just as there is an academic void regarding the history of Asante under colonial rule, so too is the history of Muslim presence in the region under colonialism still to be written. It is quite astonishing how small the corpus of sources on Muslim communities in Asante under colonial rule in the local archives is. It seems as though the colonial institutions did not devise any specific policies aimed at Muslims in the region, despite considering them a disparate group (cf. Hiskett Reference Hiskett1980: 136–7; Kobo Reference Kobo2012: 74, 88, 92). They repeatedly tried to establish customs or a ‘kola tax’ at the major trading ports, but the sources are full of complaints about the traders’ ‘illicit’ smuggling activities and the futile attempts to control the trade.Footnote 20 The traders dodged the tax collectors by changing their routes or by turning to the sea (Abaka Reference Abaka2005; Goody Reference Goody, Vansina, Mauny and Thomas1964: 207; Lovejoy Reference Lovejoy1980).Footnote 21 Although the colonial institutions apparently failed to gain control of these trading networks, their attempts to do so had consequences.

Figure 3 Processing kola in Kokote Zongo, 2011.

The case of Malam Sallow, who acted as Kumase’s sarkīn zongo (‘chief’ of the zongo) from 1919 until his deportation to Nigeria in 1932, sheds some light on how the colonial institutions attempted to place the zongos under their (in)direct rule. There is some documentation of this case, and Brian Winchester (Reference Winchester1976: 49–52) and Enid Schildkrout (Reference Schildkrout1978: 198–205) also describe the quarrels relating to him.Footnote 22

Sallow was unanimouslyFootnote 23 elected as sarkīn zongo of Kumase on 1 October 1919 by the ‘ethnic headmen’ of the zongo to succeed his predecessor, Malam Osman. During his reign, the colonial institutions established the Native Jurisdiction Ordinance, which granted the local ‘chiefs’ certain judicial rights in their (assumed) communities and created a new institution, the Kumase Zongo Court, over which they had Malam Sallow presiding. Sallow and his councillors arbitrated in cases of cattle and land dispute as well as on charges involving witchcraft. This court had judicial rights over the people of the zongo only and was not accepted by the Asante rulers. Nor was Malam Sallow accepted as ‘chief’ by the Kumasehene (the former Asantehene, Prempeh I, who had returned from the Seychelles in 1926), as this title and position were a prerogative of the Asante. While Malam Sallow seems to have had the support of the British and a large following among the Hausa, members of other ethnic groups in the zongo did not acknowledge him as sarkī. This held especially for the ‘Lagos’ or Yoruba people, who wanted to establish their sarkī, Sulley Lagos, as paramount ruler in the zongo. This resulted in several quarrels between these camps in the 1920s,Footnote 24 which were brought to a standstill in 1929 through the expulsion of Sulley to Nigeria, as ordered by Malam Sallow. However, these clashes and the levies Sallow tried to raise from his subjects made him quite unpopular among the people of Kumase’s zongos. In 1932, Malam Sallow crossed a line by ordering the flogging of the Yoruba imam who had refused to rise from the floor to greet him – a sign of respect, which, according to the imam, was to be rendered to Allah only and not to fellow humans.Footnote 25 The people of the zongo widely refused this order, as they considered it outrageous. Several ‘headmen’ from the zongo opposed it and asked the colonial institutions for Sallow’s deportation to Nigeria. This resulted in further clashes, which prompted the colonial institutions to deport Sallow to Lagos by the end of the year. That put an end to the clashes that had been so harsh and brutal that up to the early 1950s the people of the zongo were opposed to Sallow’s return to Kumase.Footnote 26 Nevertheless, the ethnically based quarrels, which still mark the politics of the zongos today, continued.

Throughout these events, the colonial institutions constituted a ‘higher’ violence and finally intervened through the deportation of Sallow, but this was not a decision taken by them. I will quote an administrative letter from 26 September 1904, which concerns colonial involvement in ‘chieftaincy affairs’. This dates from much earlier in the twentieth century, but the basic stance does not seem to have changed much. According to the Colonial Secretary’s letter, in ‘chieftaincy matters … the interference of the British Representative [was to be] limited to the confirmation or non-confirmation of the action of the people’.Footnote 27 Colonial rule changed the political context significantly, as it abolished the Asanteman and created a political void in which the zongos could emerge, but its impacts on local processes seem to have been indirect and reactive (Rouch Reference Rouch1956: 52).Footnote 28

The colonial institutions made another major attempt to gain control of the zongos through the Muhammadan Marriage Ordinance (Hanretta Reference Hanretta, Becker, Cabrita and Rodet2018; Hiskett Reference Hiskett1976). According to this ordinance, only ‘priests’ in possession of a ‘licence to a Muhammadan priest’Footnote 29 were officially allowed to conduct Muslim marriages. These ‘licences’ were priced at one pound and sold to those able to prove that they were Muslim scholars by signature of an ethnic ‘headman’. Yet again, this attempt proved futile. In 1944, the records state that ‘registration is not in vogue’, and in 1951 only seven marriages were recorded by the colonial administration for the whole year, while roughly 40–50 were assumed to take place in Kumase’s zongos every month.Footnote 30 Again, the zongos and their inhabitants seem to have eluded the attempts of the colonial institutions to place them under formal rule and administration.

Within the zongos, people got involved in the developing national politics and formed political associations (Winchester Reference Winchester1976). In 1932, some Muslims founded the Gold Coast Muslim Association in Accra, which adopted as its main objectives the welfare, education, and social security of Muslims (Ahmed-Rufai Reference Ahmed-Rufai2002: 108). This originally apolitical organisation turned into the Muslim Association Party (MAP) in 1951 (Ahmed-Rufai Reference Ahmed-Rufai2002: 108; Allman Reference Allman1991: 1–2; Hanretta Reference Hanretta2011: 189–90; Winchester Reference Winchester1976: 55). As a party, the MAP attempted to represent Muslim interests and to rally Ghana’s Muslims under its banner. However, from its very beginnings, the MAP was and remained ‘a distinctly southern, urban phenomenon, rooted in the stranger communities or zongos’ (Allman Reference Allman1991: 3). Neither in the northern territories nor among other Muslims did they meet with success (Ahmed-Rufai Reference Ahmed-Rufai2002: 108; Allman Reference Allman1991: 15; Hanretta Reference Hanretta2011: 190). Like the National Liberation Movement (NLM), which strove to consolidate and represent Asante interests in the political arena, the MAP took an oppositional stance towards Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP), which became the main political union in the struggle for independence (Allman Reference Allman1991: 2, 4; Kobo Reference Kobo2009: 520; Rouch Reference Rouch1956: 163–4; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1974b: 118–19). In the 1954 elections, the MAP suffered a severe defeat (Hanretta Reference Hanretta2011: 193), and, after independence in 1957, Nkrumah banned religious, ethnic, and regional parties in order to oust his political adversaries and to consolidate the emerging nation. The leaders of the MAP were expelled, which dealt a severe blow to their organisation (Allman Reference Allman1991: 10, 21; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1974b: 119) and gave more than a hint of the emerging state’s future dealings with its ‘aliens’. What remained of the MAP merged with other oppositional associations into the United Party in 1958 (Allman Reference Allman1991: 21). The MAP’s attempt – and failure – to devise Muslim politics in Ghana has been the only such attempt so far. Since independence, Ghana has experienced various changes and crises, but it has not seen sectarian politics again.Footnote 31 This history bears witness to two facts. One is the fragmentation and heterogeneity of the Muslim community in Ghana (Hanretta Reference Hanretta2011: 218–19).Footnote 32 The other is that Muslims in Ghana did and do not refrain from involvement in local or national politics; this is a quite different attitude from the ‘Suwarian tradition’ adhered to during the Asanteman. Muslims in Ghana were not and are not apolitical per se. Today, they are enrolled in the major political parties, representing Muslim as well as other interests (Kobo Reference Kobo2010; Ryan Reference Ryan1996: 319).

The emergence of the Tijaniyya as the hegemonic Islamic group, 1900s–1970s

During the first half of the twentieth century, the Muslim presence in Asante underwent major changes. There was a steep rise in numbers, and the Tijaniyya emerged as the major Islamic group during the 1920s. Originally, these were itinerant scholars who competed with the Qadiriyya and attempted to reform local Islamic imaginaries, conceptions, and practices. The quarrels between scholars of these orders lasted several decades until 1952, when Ibrahim Niasse visited Kumase. The repercussions of this event marked the final displacement of the Qadiriyya by the Tijaniyya as the predominant Islamic group in the zongos; the Tijaniyya were to hold Islamic hegemony there for the next 20 years.

Ibrahim Niasse (1900–75) was born in the early twentieth century in Senegal. He was the son of a prominent Tijaniyya sheikh, al-Hajj Abdallah al-Niyasi, from whom he received his early Islamic education (Hiskett Reference Hiskett1980: 101; Seesemann Reference Seesemann2009; Reference Seesemann2011; Triaud Reference Triaud, Triaud and Robinson2000). In his early thirties, he claimed to be the ghawth al-aʿẓam (saviour of the age) and began to propagate his tenets. In 1932, he moved to the outskirts of Kaolack, established a madrasa and zāwiya (Sufi lodge), and gathered his adherents to form the jamāʿat al-fayḍa (Congregation of the Flood of Grace).Footnote 33 In the 1940s and 1950s, Niasse undertook several journeys in the subcontinent to spread his teachings and his fayḍa and gained a large number of followers all over West Africa (Hill Reference Hill2007: 7; Hiskett Reference Hiskett1980: 100–1; Seesemann Reference Seesemann2011). In present-day Ghana, his portrait is found all over the zongos as paintings on walls, stickers on cars, or amulets. Many local Tijaniyya venerate him as wali (someone close to or favoured by Allah) and refer to him as the founder of their order.Footnote 34

To write a history of the Tijaniyya in Asante, I draw on interviews with some of their major scholars in Kumase.Footnote 35 Today, the Tijaniyya in Kumase are divided into two wings, and the history of the Tijaniyya in Ghana is a contested issue. Although the members of these wings do not narrate disparate histories, the central protagonists differ in their versions. The Cisseyfoɔ (the people of Hassan Cissé, the successor of Niasse in Kaolack) tend to neglect the role of Maikano Jallo, stressing the ‘Big Six’ instead; the Jallofoɔ (the people of Jallo) tend to do the opposite. A book on the history of the ‘Big Six’ written by Abdul Wadud, the leader of the Cisseyfoɔ, was widely welcomed by the Cisseyfoɔ, while the Jallofoɔ objected to it for omitting Maikano Jallo. The resulting disagreements prompted Abdul Wadud not to reprint it.Footnote 36 The narration of this history is heavily contested, as it is ingrained in and legitimises the current state of affairs, and so the competing wings narrate it differently.

Nonetheless, they agree that the Tijaniyya emerged in Asante during the early twentieth century. These were mainly itinerant scholars from northern Nigeria, and the first local malam to become a Tijaniyya was Sheikh Umar (or Haruna) Karki (mid-nineteenth century–1934) from Salaga.Footnote 37 Sheikh Wali Ullah stated that Sheikh Umar was originally a Qadiriyya, but during his hajj, he met a grandson of Ahmad Tijani who initiated him into the ṭarīqa at-Tijaniyya and made him a muqaddam (a guide, or someone who initiates others into the Tijaniyya). After his return to Salaga, he founded a makarantā and occasionally ventured to Kumase to spread his teachings there. In 1894, a civil war left Salaga devastated and he had to resettle in Kete Krachi, where he lived and taught for the rest of his life. He was the first local malam to propagate the Tijaniyya in the region, but he did not settle down or build a makarantā in Kumase. Malam Babali did so in 1907Footnote 38 and was thus the first Tijaniyya muqaddam to settle in Asante; before that, he was also working as an itinerant scholar. Babali was a Tijaniyya by birth and well versed in the ṭarīqa’s tenets and practices. His makarantā became a renowned centre for Islamic learning, and his mawlid (celebration of the birthday of the prophet) attracted many people from the zongos, assuring him a growing number of adherents. His main rival was Malam Abdullahi Tano,Footnote 39 a Qadiriyya, who led the jumʿa at Kumase’s Central Mosque and ran his own makarantā. They remained rivals throughout their lives, in open competition, but in the late 1940s the odds started to shift in favour of the Tijaniyya.

In 1946, Sheikh Hadi Mawlud Fall from Mauritania, a disciple of Muhammad al-Hafiz,Footnote 40 visited Kumase to preach on behalf of the Tijaniyya. Malam Babali hosted him, and his sermons attracted a significant crowd. Another major Tijaniyya scholar, Sheikh Omar from Fes,Footnote 41 came to town in 1948 and again attracted many people. The two visitors contributed to the increasing reputation of the Tijaniyya, thanks to their sermons and the miracles they are claimed to have worked. They also sparked rumours about a ‘black sheikh’ in Senegal by the name of Ibrahim Niasse. Ibrahim Niasse first arrived in Ghana in 1946, stopping only in Takoradi and Tema on his way to Nigeria. Consequently, the rumours gained traction and people grew eager to meet this famous sheikh. In 1948, a delegation left Kumase for Kaolack to participate in the mawlid and to invite Niasse to bless the town with his visit. In December 1951, Niasse made it to Kumase, where he spent a few days before moving on to Yendi. This was his first and only visit to the town (though not to Ghana) and marked the beginnings of Tijaniyya hegemony in the zongos. By this time, Malam Babali was already dead, or at the end of his life, and Niasse was hosted by some young and aspiring malams who were to become Kumase’s Tijaniyya ‘Big Six’.Footnote 42

Abdul Wadud related the most detailed account of Niasse’s sojourn in Kumase. Despite his version of Tijaniyya history in the region being quite sympathetic to Maikano Jallo, the Jallofoɔ commonly criticised him for downplaying their ‘spiritual leader’. Nonetheless, Abdul Wadud is widely acknowledged as an authority on this history, as he is not only a son of one of the ‘Big Six’ but also a pupil of Maikano Jallo. In substance, I found his narration corroborated by other versions. Therefore, I retell it in detail as an authoritative account:

Niasse arrived by train in Kumase on a Thursday afternoon during Ramadan in December 1951.Footnote 43 Rumours about his coming had spread in town and attracted a massive crowd of several thousand people to the station, eager to see the sheikh and get his blessings. The station was so crowded that one could neither leave nor enter it. The crowd chanted songs of prayer and praises and grew enthusiastic at Niasse’s arrival, who could not have left the station if it was not for his prayers. Once he had greeted and blessed the crowd, he opened his hands towards the sky, said a short prayer, and raised his gaze upwards. On the spot, dark clouds assembled in the hitherto clear sky and poured their rain on the crowd, which quickly dispersed, giving way to Niasse and his entourage.

The days before this visit, the people of the zongo had been busy weeding a large area not far from the palace of the Asantehene where Niasse was supposed to lead the prayers and to preach during his stay. On Friday, a large crowd assembled to offer the jumʿa behind Niasse who blessed the place by this very prayer. Even the non-Muslims became aware of his spiritual presence, which prompted the Asantehene to give the Muslim community this piece of land for the construction of a mosque. Thus, Kumase’s Central Mosque was founded and blessed by Niasse.

The third miracle Niasse worked during his stay was to cure a poisonous snakebite. A woman, who had helped in the weeding, had been bitten by a snake and lay there sick and dying. When Niasse heard of this, he instructed his host, Baba Makaranta, to attend to her and to recite certain āyāt (verses) over the bite to neutralise the poison. Thanks to this, the woman recovered and could participate in the jumʿa on the same day.

From Kumase, Niasse continued his journey to Yendi. Upon his arrival there, he pointed his right index finger to the sky and proclaimed Lā ilāha illā Allāh (There is no god except God), and every living being in town, from the smallest insect to the oldest human being, replied to his call, stating Lā ilāha illā Allāh. On that day, 4,000 people embraced the religion of Islam, which is the largest single conversion known in the history of this religion in Ghana.Footnote 44 These are some of the wonders Niasse worked during his stay. Truly, this was a man of God.

In this history, Niasse is presented as a wali and as being imbued with divine baraka (divine presence, blessings), which enabled him to do miraculous things. This narration also bears witness to his visit to Kumase, which marked the beginnings of Tijaniyya hegemony. Henceforth, his hosts and companions were regarded as major Islamic authorities and addressed on any religious matter. The Qadiriyya scholars and their tenets fell into oblivion.Footnote 45

These scholars were to become the Tijaniyya ‘Big Six’.Footnote 46 In some narrations, all of them were presented as students of Malam Babali; in others, some were trained by Babali and others by Malam Abdullahi Tano. However, after Niasse’s visit, they are all presented as Tijaniyya. The six scholars were:

1. Sheikh Muhammadu Kyiroma, who, from 2 January 1952 until his death on 1 August 1968, acted as Kumase’s ‘chief imam’,Footnote 47 in which role he succeeded Malam Tano, and as one ‘head’ of the Imamiyya makarantā;

2. Sheikh al-Hajj Baba Makaranta, the only one who was not a malam; he was a quite successful businessman and acted as host to Niasse and as financier of the Tijaniyya;

3. Sheikh al-Hajj Haruna, the other ‘head’ of the Imamiyya makarantā;

4. Sheikh Ahmed Baba al-Wa’iz,Footnote 48 Niasse’s spokesman and interpreter during his visit and ‘head’ of the Wataniyya makarantā;

5. Sheikh al-Hajj Alhassan Nasserudeen, who ran his own makarantā; and

6. Sheikh al-Hajj Abubakar Garba Hakim, Kyiroma’s nāʾib (deputy imam) and ‘head’ of the Hakimiyya makarantā.

The first three were brothers, stemming from the same Hausa-Fulani house and family. Nasserudeen was a Dagomba, and the other two were Hausa. From their beginnings, the Tijaniyya were thus not confined to any kin or ethnic group. Apart from Baba Makaranta, these malams ran their own makarantā where they spread their tenets and practices, further solidifying their religious hegemony in the zongos. Haruna and Kyiroma presided over the Imamiyya, Garba Hakim over the Hakimiyya, Nasserudeen over the Nasserudeen makarantā, and Baba al-Wa’iz over the Wataniyya. According to Abdul Wadud, who was trained at the Imamiyya makarantā of his father, the majority of Ghana’s current imams received their training from these schools.Footnote 49 These makarantā were the major institutions of Islamic learning in Asante from the 1950s to the 1970s, the two decades that marked the height of Tijaniyya hegemony in the zongos.

However, even during these years, the Tijaniyya were not the prevalent Muslim denomination. At its very height, 30–40 per cent of Ghanaian Muslims are assumed to have been explicit adherents or initiated members of the ṭarīqa (Hiskett Reference Hiskett1980: 109–15; Stewart Reference Stewart1965: iiin), while the others were mainly ‘just’ nkramo. However, the majority of the local imams and malams were initiated into the ṭarīqa and they taught and practised its tenets, which were thus quite popular among local Muslims, whose huge repertoire of Tijaniyya praise songs bears witness to this fact (Hiskett Reference Hiskett1980: 112–14; Viola Reference Viola2003). The Tijaniyya were therefore highly influential on local imaginaries, conceptions, and practices of Islam, but they did not create them ex nihilo, nor were they the only Islamic group. Their rise entailed neither a replacement nor a reformulation of many local Islamic tenets and practices, such as funeral prayers or the manufacture of Islamic amulets. Several Tijaniyya interlocutors stressed that these practices derive from what they called ‘traditional Islam’ and were already present when the Tijaniyya emerged as hegemonic. In the process, they took over those practices that did not go against their tenets or the Sunna, but they were not their originators. Nor did the Tijaniyya form an organisation, as these were malams who cooperated and concurred on many fronts, not a unified movement. The Tijaniyya thus contributed to and reshaped the Islamic landscape, but they neither carved it anew nor altered it entirely.

Muslim presence in the Ghanaian nation state: unsettled integration, 1957–today

Independence lifted the lid on a question that had been silenced by colonial rule: whether to integrate the people of the zongo, most of whom were immigrants, into the emerging nation. For the colonial institutions, the people of the zongo were colonial subjects like other Africans; for the emerging nation and its identity politics, the questions of autochthony, belonging, and citizenship took a different turn. This became manifest not only in Nkrumah’s banning of religious, regional, or ethnic parties, but also in the state’s treatment of national ‘aliens’. The fault line of the emerging Ghanaian nation rendered the people of the zongo ‘aliens’, and they became subject to rampant xenophobia and discrimination.

The Gold Coast colony declared independence from Great Britain and became the nation of Ghana on 6 March 1957. Just like the history of Asante under colonial rule, the history of Asante during and after independence is still to be written (McCaskie Reference McCaskie1986b: 3; Wilks Reference Wilks1996).Footnote 50 However, some research on the history of Muslims in the Ghanaian nation state has been conducted, and we can draw on the work of Ousman Kobo (Reference Kobo2009; Reference Kobo2010; Reference Kobo2012) and Yunus Dumbe (Reference Dumbe2013) to sketch a picture of these times. The Ghanaian constitution granted citizenship to those who had a Ghanaian parent or grandparent (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 74). This excluded many people of the zongo, most of whom were born to foreigners. With independence, the people of the zongos found themselves in the Ghanaian nation, where their status was quite ambiguous. On the one hand, they were considered legal residents; on the other, they remained strangers in their respective surroundings. In the first Ghanaian Republic under Nkrumah, which lasted from 1957 until the military coup in 1966, there were no specific policies on the zongos. As Nkrumah strove for national consolidation and infrastructural modernisation, minority policies were not a major issue. However, growing Ghanaian nationalism resulted in an increasing ‘xenophobia toward northerners’ (Allman Reference Allman1991: 17) or ‘a growing resentment of foreigners’ (Peil Reference Peil1971: 209). The people of the zongo became ‘outsiders’ and were singled out as scapegoats for Ghana’s woes (Peil Reference Peil1971: 217; Reference Peil1974: 373; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1974b: 135; Winchester Reference Winchester1976: 179–81; Kobo 2010: 79).

These developments also had an impact on Islam and religious leadership in the zongos. In the years after independence, the Asante Nkramo challenged other Muslims over the right to provide the imam of Kumase’s Central Mosque and claimed paramount status in the regional umma. This was less a question of theology or religious practice; it was about ethnicity. As the Asante Nkramo openly challenged the ‘aliens’ of the zongos as a whole, these ‘aliens’ coalesced in opposition to them. The tensions turned into open conflict in 1968 when the Asante Nkramo claimed priority to designate the successor to Kyiroma, the late imam. Their ethnic claim was strongly resented, and the affair erupted into open conflict and violence (Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1974b; Winchester Reference Winchester1976: 65–6).

When Kyiroma died on 1 August 1968, the members of the Ghana Muslim MissionFootnote 51 under the leadership of Adam Apiedu designated a certain Nasserudeen as his successor. This met with the refusal of the Muslims of the local zongos, who turned their administrative designation as ‘Muslim Community’ into a (short-lived) organisation and letterhead. The ‘Muslim Community’ declared al-Hajj Adam as successor against Nasserudeen. Festering tensions boiled over into open violence, and the Central Mosque became locked down for several months.

In an official letter of 26 August 1968, the Ghana Muslim Mission demanded that ‘Islamic affairs should be left in the hands of Ghanaians’, as it was ‘high time [that the Hausa] gave “independence” to the indigenous citizens who have embraced the religion and who are now in a better position to manage their own affairs’.Footnote 52 The Brong Ahafo/Ashanti Branch of the Mission used an even harsher tone in an official letter from 27 August 1968, by demanding an end to the ‘tyranny [of] the black imperialism of the Nigerian Hausas in the Islamic Religion in Ghana’. In response to these demands, the leaders of the ‘Muslim Community’ held a press conference in Kumase on 30 August 1968, declaring that ‘the choice of an Imam is based on experience, good character, tolerance and good moral standards’, and that the Ghana Muslim Mission is ‘quite a separate Mission’ who could have ‘their own Imam’. They restated this in an official letter on 7 September 1968, in which they claimed that they represented ‘50,000 … muslims from various tribes in Ghana and foreign nationals [while the] rebel group are just a little over 3,000’. They claimed to represent the majority of Muslims in the region and therefore should have the imam of Kumase’s Central Mosque coming from their ranks.

This conflict simmered on for several months, with the situation changing only in late 1969 when the Ghanaian president, Kofi Abrefa Busia, started a campaign against national aliens. These developments severely weakened the ‘Muslim Community’ and led to them accepting the ‘Mission’ imam (Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1974b: 133).

After the overthrow of Nkrumah in 1966, the politics of nationalisation and the ousting of alleged others increased in severity. Although many people of the zongo had received Ghanaian citizenship under Nkrumah, the new politics attempted to deny them these rights and to (re)classify them as aliens. The Ghanaian government’s various ‘Alien Acts’ of the 1960s were part of these developments (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 74–7; Peil Reference Peil1971: 206). National chauvinism searched for its other and found it in the people of the zongo, who had to face disadvantage and insecurity from the Asante and the national government alike.Footnote 53 In a speech, Kofi Abrefa Busia labelled the people of the zongo as ‘strangers’ and ‘not a true Ghanaian at all’ (Hanretta Reference Hanretta2011: 220). These developments culminated in the ‘Aliens Compliance Order’ of 18 November 1969 and in the mass expulsion of national aliens in 1971 (Kobo Reference Kobo2010; Peil Reference Peil1971; Reference Peil1974). Within a short time, many inhabitants of the zongos left the region to avoid expulsion or found themselves expelled by the state. Margaret Peil estimates that 200,000 people – roughly half of the country’s migrant population – were forced to leave Ghana within six months (Peil Reference Peil1974: 367). Although many of these people had been born in Ghana, they had inherited the ‘alien’ status of their parents (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 82). These events are well remembered by the people of the zongo today. Many of them possess Ghanaian passports and consider themselves Ghanaian, but they feel insecure about their status in the Ghanaian nation, where they have remained strangers within (Hargreaves Reference Hargreaves1981: 97–8; Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 83; Pellow and Chazan Reference Pellow and Chazan1986: 102; Quayson Reference Quayson2014: 203–6; Schildkrout Reference Schildkrout1970: 269).

The deportations were immediately suspended by General Ignatius Kutu Acheampong after he seized power from Busia in a coup d’état in January 1972 (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 83–4). Acheampong realised the potential support his government could gain from the zongos and strove to establish himself as a protector of the zongos and their Muslim inhabitants, following Nkrumah’s line of cooperation with local imams (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 84–6). The zongos’ support aided his success in the 1975 referendum to confirm his rule (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 87). Those succeeding him in the following decades took note of this elective success – especially Jerry John Rawlings, who ruled Ghana from 1981 to 2001 and who had a keen interest in maintaining good relations with the zongos to ensure their inhabitants’ votes (Kobo Reference Kobo2010: 89–90) – and the zongos have been perceived as a voting bloc ever since. Muslim votes can be decisive in the usually close elections between Ghana’s two major parties: the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). The former is frequently perceived as a ‘zongo’ or ‘northerner’ party; this is due less to its politics than to its rhetoric and the fact that the NPP is the successor to Busia’s United Party, which was responsible for the mass expulsion in 1971. However, Muslims are enrolled in both parties, neither of which is widely perceived as or presents itself as Islamic.

The attitude of the Ghanaian state towards Muslims in its territory is thus rather ambivalent. On the one hand, Muslims are in the majority in its northern regions, are Ghanaian citizens, and are desired voters; on the other, they are assumed to be aliens and are often subject to xenophobia. Zongos are frequently designated as places of poverty, filth, violence, and crime. ‘They give birth too much’, ‘they are dirty’, and ‘they are criminals’ – these are some of the prejudices I encountered among the Asante. Frederik Lamote met with similar prejudices towards ‘northerners’ among the people of Techiman, who designated them as ‘barbarians’ and ‘undeveloped’ (Lamote Reference Lamote2012: 151). The internal dynamics and history of these wards are unknown to the Asante.

The emergence of the Sunna and the rise of Maikano Jallo, 1970s–2000s

The 1970s saw massive changes in the Islamic field of the zongos. The turmoil of the mass expulsions of 1971 and their aftermath had left a deeply unsettled and disrupted community. Unfortunately, I have not come across any substantial sources recording the ways in which the people of the zongo experienced these events, and my interlocutors refused to talk about them in detail. Within a few months, about 200,000 people – about half of the zongos’ population – were forced to leave the country, taking their trade and connections with them.Footnote 54 According to some interlocutors, the wealthier traders pre-empted their expulsion and left Ghana before the enforcement of the expulsions, which thus hit an already impaired community. In Kokote Zongo, these events are commonly remembered as ‘mmerɛ no a, ɔmɔapam kurom’ (‘the times when they [the Ghanaian state] have expelled the people from town/left the town deserted’). Those who remained found themselves facing rampant xenophobia, in shock, extremely insecure about their status, and with severely disrupted neighbourhoods and trading networks. In retrospect, this marked the beginning of the end of the zongos’ once bustling trade, and, to this day, the people of the zongo deeply mistrust the Ghanaian state due to these events. The deep scars that these have left on the people and their collective memory were apparent in the consternated silences after I asked about these events or when someone alluded to them, as well as in the overall refusal to talk about them in detail. Back in the 1970s, the zongo communities were deeply troubled, socio-economically devastated, and socially disrupted. They had to rebuild themselves on shaky ground, and thus the Muslim students who returned from the Arab world, arriving in Ghana as fully fledged but not yet established Islamic scholars, came back to a deeply unsettled community whose former cohesion had experienced a severe disruption and was only slowly beginning to rebuild. The reformists among these returnees, who were to form the Sunna, thus found space to manoeuvre as they drew on previous attempts at Islamic reform in the region to assert their own.

Over the centuries, Muslim scholars in West Africa have been highly mobile, especially the younger ones who had to build a reputation before people started coming to them, enabling them to settle down and to set up structures of teaching and preaching. These itinerant scholars created an ‘Islamic sphere’ (Launay and Soares Reference Launay and Soares1999) that transgressed ethnic, colonial, national, and other boundaries. As reported by Lansiné Kaba (Reference Kaba1974), attempts at an Islamic reform oriented towards or influenced by contemporary teachings in the Arab world have been undertaken by local actors in West Africa at least since the early twentieth century. However, this did not imply a historical break or the emergence of a completely new phenomenon. Muslims in West Africa have always exchanged ideas with Muslims in other regions of the world. Historically, the hajj was the main means of this exchange, although not all travelled that far to gain or to spread Islamic knowledge. The Islamic reform movement in the zongos was preceded by Afa Ajura in Tamale and Adam Apiedu in Kumase, both of whom were active during the first half of the twentieth century. The Sunna emerged in Ghana during the 1940s and campaigned against the Tijaniyya from the outset, but, during the movement’s genesis, their influence and adherence were limited to a few cities. This changed in the 1970s, when numerous Muslim scholars returned from their Islamic studies in the Arab world, established makarantā, and held public sermons throughout the region (Dumbe Reference Dumbe2013; Kobo Reference Kobo2009; Reference Kobo2012; Reference Kobo2015; Samwini Reference Samwini2006).

Yet, not all returnees adhered to the same teachings, they were not all Wahhabi or Salafi, nor did they all campaign against local ‘deviations’ or ‘syncretism’ (Kaba Reference Kaba1974: 51).Footnote 55 In an interview I did with a Sunna malam in Kumase, he claimed that every Ghanaian Muslim who had gone to study in the Arab world returned as Sunna: ‘How could it be otherwise?’ However, I met several Tijaniyya malams who had studied in the Arab world, and, while they cherished what they had learned there, they did not return as Sunna. Nonetheless, some – perhaps the majority – of the Ghanaian Muslims who had studied in the Arab world in the 1960s returned as reformists, and it was from this body of returnees and their adherents that the Ahl us-Sunna wal Jama’ah emerged. Unfortunately, statistics on these students are unavailable, but the Sunna malam stated that the alumni involved with the Sunna totalled a little more than 300 persons.

However, the first Muslim scholars to voice an open critique of the Tijaniyya and their tenets were not returnees but locally trained malams. In the 1940s, Afa Ajura preached sermons and opened a Qur’anic school in Tamale. His anger was roused especially by the Tijaniyya tarbiya and their proclaimed ability to ‘see God’, and he campaigned against these (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim2002: 102). This resulted in a ‘give and take’ of sermons that involved several malams who openly challenged each other’s teachings and preaching (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim2002: 96–101; Iddrisu Reference Iddrisu2009: 23–4; Kobo Reference Kobo2012: 156–71). In the 1960s, Adam Apiedu, an Asante Nkramo from Kumase, began to openly criticise the Tijaniyya as well. He singled out the manufacture of amulets and funeral prayers for his criticism; in time, he gained a significant following, albeit predominantly among the Asante Nkramo (Kobo Reference Kobo2012: 171–80). But these two remained isolated figures (Iddrisu Reference Iddrisu2009; Kobo Reference Kobo2012). Afa Ajura remained cut off from other Islamic scholars in Tamale, while Adam Apiedu was marginal in the zongos. Nevertheless, the two voiced influential critiques of the Tijaniyya that were taken up and amplified by the following generation of Sunna malams.

My Sunna interlocutors commonly referred to the early 1970s as the time of their establishment. During these years, several of them returned from their Islamic studies in the Arab world and propagated Wahhabi or Salafi tenets in their sermons and through the schools they founded. The most prominent of these scholars is al-Hajj Umar Ibrahim, the present ‘national chief imam’ of the Ahl us-Sunna wal Jama’ah. He returned to Ghana in 1969 after nine years of studies at the Islamic University of Medina and established himself as a malam in Nima, Accra’s biggest and Ghana’s most renowned zongo (Dumbe Reference Dumbe2013; Kobo Reference Kobo2009; Reference Kobo2012). He started to preach and teach in a friend’s house and attracted the interest of many. Out of these sermons and classes, Ibrahim and his followers formed the Ghana Islamic Research and Reformation Centre, which they legally formalised in 1972. This institution is popularly known as ‘Research’ among Ghana’s Muslims and has a reputation as the country’s major centre of Islamic learning among all Muslims in the region.Footnote 56 The school attached to this centre was one of the first Islamic schools in the country to offer a senior education. Thanks to the connections of its founder to the Arab world, it could offer stipends to its students, and this contributed significantly to its attractiveness. It cannot be overemphasised how influential this school was and is within the Ghanaian umma (Dumbe Reference Dumbe2013: 53–8; Kobo Reference Kobo2012: 213–30). Thanks to their schools and sermons, the Sunna thus gained a prominent voice in Islamic discourses. They not only challenged the Tijaniyya and their tenets; they also fundamentally changed the Islamic field, calling into question several ideas and practices that had been considered Islamic until then.

In Kumase, al-Hajj Abdul Samad emerged as the first local Sunna malam.Footnote 57 Originally, Samad had been a Tijaniyya but during his hajj in 1970, he abandoned their teachings and adopted Wahhabi tenets, which he then preached in Kumase. At that time, the majority of Kumase’s mosques were under the Tijaniyya, and he was denied entry to them. Thus, he and his followers held evening sermons in front of houses, at lorry stations, or in market places. Several of these events descended into violent clashes, and several malams found themselves imprisoned overnight. The clashes were so violent that the police denied Umar Ibrahim entry to Kumase in 1973 to prevent him from preaching there. However, Abdul Samad and his followers continued their campaign and built their own school and mosque in Sabon Zongo, just behind Kumase’s Central Mosque. For the Tijaniyya, the sermons of Abdul Samad were not only outrageous because he criticised their tenets; as a former Tijaniyya, he had been initiated into their ʿilm bātinan (covered knowledge) which he now exposed and ridiculed in his sermons. This met with deep resentment on the part of the Tijaniyya, among whom Samad was considered to be ‘arrogant in character and corrupted in his heart’, as one Tijaniyya sheikh put it in an interview. Yet, physical attacks did not prevent him and his followers from spreading their tenets. At that time, the remaining ‘Big Six’ were quite old and inexperienced in holding sermons in defence of their tenets and practices, as they had not been challenged in this way before. Therefore, they called for Maikano Jallo, a Tijaniyya malam, who had earned a certain reputation as an ardent preacher for the cause of the Tijaniyya thanks to his confrontations with Afa Ajura in Tamale during the 1960s (Dumbe Reference Dumbe2013: 44; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim2002: 103–7; Kobo Reference Kobo2012: 167–8).

Figure 4 Poster at the mawlid in Prang, 2012. From the left: Maikano Jallo, Abdul Failih, and Ibrahim Niasse.

The most famous of these confrontations centred on the ṣalāt al-fātiḥ:

Over the course of the 1960s, the tensions between the Tijaniyya and the followers of Afa Ajura in Tamale erupted in several clashes and open violence, which resulted in public insecurity and mutual mistrust. To appease the situation and to settle the argument ‘once and for all’, the chief commissioner of police called for the opposing parties to debate their conflict in front of an audience in Tamale’s central park in 1968. Beforehand, the two sides agreed on taking the value and the religious merit of the ṣalāt al-fātiḥ,Footnote 58 a major prayer of the Tijaniyya, as the topic of their debate.

Afa Ajura came with his followers and had his whole library assembled on stage. As he was to start the debate, he stepped forward, greeted the organisers, his opponent, and the crowd, before he posed a challenge to Maikano Jallo. He argued that the ṣalāt al-fātiḥ was a nice prayer, as it praises the prophet and asks for his blessings. However, he denied it any major value among the other Islamic prayers, as it was not to be found in the Qur’an, the Sunna, or any other major Islamic book. Therefore, he had brought his whole library to place it at the disposal of his opponent. If Maikano were able to find the ṣalāt al-fātiḥ in one of his books, he would renounce his teachings and preaching and gladly embrace the Tijaniyya. Then, Maikano stepped forward, greeted the organisers, his opponent, and the crowd in turn, and claimed that he did not need any library to make his point and asked for just a Qur’an. Having fully memorised the Qur’an, he could have quoted it by heart, but he wanted to prove materially that he was quoting only the word of God. He opened the Qur’an, sura 10, Yūnus, āya 9, and read: ‘Allāhumma …’ He went on to sura 33, al-Ahzāb, āya 56: ‘salli Allāhi wa sallim …’ In this way, he recited the entire ṣalāt al-fātiḥ piecemeal from the Qur’an, while the crowd started cheering and praising Allah.

My interlocutors generally agreed on this, but they diverged on the question of who had won the debate. The Tijaniyya thanked Allah for this brilliant scholar who had so much insight into the Qur’an and its hidden knowledge that he could recite the ṣalāt al-fātiḥ from it;Footnote 59 the Sunna considered it a disgrace for any Islamic scholar to read the word of God in this way. Thus, both sides claimed that they had emerged victorious. Whoever might have won or lost, the conflicts in Tamale were not settled, and Maikano had to leave the city. Some people cite this as proof of his loss, others as a sign that he was needed elsewhere to uphold the cause of the Tijaniyya – in Kumase.

Sheikh al-Hajj Baba Abdullahi Maikano Jallo (late 1920s–2005) was the most influential Islamic scholar in late twentieth-century Ghana, where he was, and still is, the most renowned face of the Tijaniyya.Footnote 60 His portrait is painted on walls, stuck on cars, or worn as a necklace. Many Tijaniyya refer to him as wali and attend to the mawlid in his home town, Prang; this mawlid is the largest single Islamic event in Ghana every year. In the 1970s, he succeeded the ‘Big Six’ to ‘carry on the light of the Tijaniyya’. A closer look at this figure provides insights not only into the career of a very influential Tijaniyya malam but also into how things changed among the Tijaniyya and in the Ghanaian umma through the emergence of the Sunna.Footnote 61

According to established narration, Maikano Jallo was born in 1928Footnote 62 in Aboasu in the Western Region. His parents were Fulani cattle traders and farmers from Prang, a village a few miles north of Atebubu in the Brong Ahafo Region. His maternal grandfather was a famous Islamic scholar and frequently hosted itinerant scholars in his house. One such visitor was an astronomer from Sokoto. As a gift of gratitude for the hospitality, he looked into the stars and divined that the daughter of his host would give birth to one male child only, and that this child would become a great Islamic scholar. When Maikano’s grandfather received news of his daughter giving birth to a boy, he realised that the divination had come true and had her bring the child. He continually prayed and prepared rubūtū (Qur’anic liquid) for him, so that from his early years Maikano Jallo was with the word of God, which he incorporated as rubūtū and teachings from his grandfather, becoming imbued with baraka, which laid the foundation for his steep rise as an Islamic scholar.