Introduction

As argued by Stone and Colella (Reference Stone and Colella1996: p. 354) disability entails ‘…a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more life activities’. Alongside making it difficult to enter the labour market (Boman, Kjellberg, Danermark, & Boman, Reference Boman, Kjellberg, Danermark and Boman2015), disability augments job demands and challenges workplace integration (Grover & Piggott, Reference Grover and Piggott2013). Disability management is conceived of as an attempt to address such issues and foster the work involvement of people living with disability, lessening job demands and improving job resources (Geisen, Reference Geisen, Geisen and Harder2016). More specifically, disability management is ‘…a systematic, cohesive, and goal-oriented approach’ which seeks the enhancement of ‘…the health of employees in order to prevent disability or further deterioration when a disability is present’ (Smith, Reference Smith1997: p. 37). In line with this understanding, three main concerns fall within disability management: (1) the prevention of disabilities on the job and off the job, (2) the minimization of direct and indirect implications of disability, and (3) the enablement of disabled people's work capabilities (Rieth, Ahrens, & Cummings, Reference Rieth, Ahrens and Cummings1995).

The scholarly debate has articulated disability management in two levels of practice (Currier, Chan, Berven, Habeck, & Taylor, Reference Currier, Chan, Berven, Habeck and Taylor2001). A human service perspective focuses on initiatives targeted at risk prevention and attempts to enhance the psycho-physical well-being of people living with disability through health promotion initiatives (Tate, Habeck, & Galvin, Reference Tate, Habeck and Galvin1986). A people management perspective deals with organizational processes and practices intended to increase the disabled people's job fit and enable them to thrive in the workplace (Gensby, Labriola, Irvin, Amick, & Lund, Reference Gensby, Labriola, Irvin, Amick and Lund2014). Although these two levels of practice have been mostly addressed independently, they appear to be strictly intertwined in disability management policies (e.g.: Bruyère, Brown, & Mank, Reference Bruyère, Brown and Mank1997; Westmorland & Buys, Reference Westmorland and Buys2004; Williams & Westmorland, Reference Williams and Westmorland2002). Elaborating on these arguments, the study provides an integrative review of extant research on disability management, with the purpose of achieving a fine-tuned account of its interplay with human resource management. Disability management is conceptualized as a complex process, involving initiatives directed at creating and maintaining an empowering workplace for people living with disability (Oranye & Bennett, Reference Oranye and Bennett2017). Rather than being sheerly targeted at work integration, disability management aims at accomplishing work inclusiveness, entailing an effort to ‘…involve all employees in the mission and operation of the organization with respect to their individual talents’ (Rice, Young, & Sheridan, Reference Rice, Young and Sheridan2021: p. 269).

Scholars and practitioners are greatly interested in organizational initiatives which are conducive to workplace inclusiveness (Carrero, Krzeminska, & Härtel, Reference Carrero, Krzeminska and Härtel2019), examining the factors which preclude underprivileged groups to flourish at work (Collins, Rentschler, Williams, & Azmat, Reference Collins, Rentschler, Williams and Azmat2022). Achieving inclusiveness is especially challenging where people living with disability are concerned, as they face tangible and intangible hurdles preventing their full participation within organizational dynamics (Kuznetsova, Reference Kuznetsova2016). Attaining inclusiveness in the workplace requires enabling people with disability (Grenawalt et al., Reference Grenawalt, Brinck, Friefeld Kesselmayer, Phillips, Geslak, Strauser and Tansey2020), making them feel committed to the organization (Simmons, Reference Simmons1995). Such empowerment process is rooted in the design and implementation of tailored human resource management practices, which should settle the cognitive, affective, and emotional issues faced by disabled employees in the workplace (Varekamp, Heutink, Landman, Koning, De Vries, & Van Dijk, Reference Varekamp, Heutink, Landman, Koning, De Vries and Van Dijk2009).

Little is known about how to enable people with disability (Waisman-Nitzan, Gal, & Schreuer, Reference Waisman-Nitzan, Gal and Schreuer2019) and engage them at work (Podsiadlowski, Reference Podsiadlowski2014). This is a major gap in the scholarly knowledge (Moore, Maxey, Waite, & Wendover, Reference Moore, Maxey, Waite and Wendover2020b), which is yet unfulfilled, despite the growing institutional concern for this topic (Ochrach, Thomas, Phillips, Mpofu, Tansey, & Castillo, Reference Ochrach, Thomas, Phillips, Mpofu, Tansey and Castillo2022) and the acknowledgement of the positive management implications generated by work inclusiveness (Moore, Handon, & Maxey, Reference Moore, Handon and Maxey2020a). Stone and Colella (Reference Stone and Colella1996) shed light on the factors determining the inclusion of disabled people in the workplace. Organizational characteristics, which ‘…include HR policies and practices related to recruitment, hiring, socialization, performance evaluation, and accommodation of persons with disabilities’, have been claimed to represent the most critical factors for disability management (Beatty, Baldridge, Boehm, Kulkarni, & Colella, Reference Beatty, Baldridge, Boehm, Kulkarni and Colella2019: p. 122). Hence, disability management is realized at the intersection with human resource management practices (Konrad, Yang, & Maurer, Reference Konrad, Yang and Maurer2016), which are essential to recognize and address the special job demands of people living with disability (Richard, Lemaire, & Church-Morel, Reference Richard, Lemaire and Church-Morel2021). Previous reviews have focused on specific human resource-related issues, such as selection and accommodation (Colella & Bruyère, Reference Colella, Bruyère and Zedeck2011), formal and informal hindrances preventing people with disability to self-realize at work (Kulkarni & Lengnick-Hall, Reference Kulkarni and Lengnick-Hall2014), human resource managers' approaches to address disability management (Ren, Paetzold, & Colella, Reference Ren, Paetzold and Colella2008), and social acceptance of people living with disability in the workplace (Vornholt, Uitdewillingen, & Nijhuis, Reference Vornholt, Uitdewillingen and Nijhuis2013). Even though these studies have delivered valuable insights about the triggers of work inclusiveness, fragmentation of perspectives does not allow us to comprehensively reconfigure human resource management in order to exploit its interplay with disability management (Bartram, Cavanagh, Meacham, & Pariona-Cabrera, Reference Bartram, Cavanagh, Meacham and Pariona-Cabrera2021), thus undermining the build-up of an inclusive and empowering workplace (Pérez-Conesa, Romeo, & Yepes-Baldó, Reference Pérez-Conesa, Romeo and Yepes-Baldó2020). Moreover, lack of systematization of scholarly knowledge prevents an exhaustive acknowledgement of how diversity management can be factually implemented to achieve organizational inclusiveness (Krzeminska, Austin, Bruyère, & Hedley, Reference Krzeminska, Austin, Bruyère and Hedley2019; Zulmi, Prabandari, & Sudiro, Reference Zulmi, Prabandari and Sudiro2021).

This literature review is original in that it arranges an overview of extant scientific literature about the intertwinement of disability management and human resource management, answering to the call for research mapping the state of the art of the debate about this study domain (Triana, Gu, Chapa, Richard, & Colella, Reference Triana, Gu, Chapa, Richard and Colella2021) and inspiring the development of an integrative framework unveiling the determinants of workplace inclusiveness (Cavanagh, Bartram, Meacham, Bigby, Oakman, & Fossey, Reference Cavanagh, Bartram, Meacham, Bigby, Oakman and Fossey2021). A hybrid – bibliometric and interpretive – literature review has been undertaken. In particular, the article tackles these questions:

R.Q. 1: What are the research streams populating the scientific debate about the interplay of disability management and human resource management?

R.Q. 2: What are the steps to establishing an inclusive workplace which succeeds in addressing the needs of people living with disability?

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the study protocol designed to collect, screen, and select relevant articles. Section 3 presents the research findings, which are framed using an interpretive approach. The results of this literature review are critically discussed in Section 4, which inspires the implications for theory and practice, as argued in Section 5.

Materials and methods

Different approaches can be used to realize a literature review (Paul & Criado, Reference Paul and Criado2020). Since our study concerned a specific research area, i.e., the intertwinement of disability management and human resource management to achieve workplace inclusiveness, a domain-based approach has been undertaken (Palmatier, Houston, & Hulland, Reference Palmatier, Houston and Hulland2018). Consistently with the study aims, a hybrid method has been used, consisting of a bibliometric analysis and an interpretive review (Paul, Lim, O'Cass, Hao, & Bresciani, Reference Paul, Lim, O'Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). A similar study design has been adopted in previous research (e.g., Ciasullo, Lim, Fakhar Manesh, & Palumbo, Reference Ciasullo, Lim, Fakhar Manesh and Palumbo2022; Palumbo & Fakhar Manesh, Reference Palumbo and Fakhar Manesh2021). This methodology enabled us to advance a comprehensive state of the art of scientific literature, combining the strengths of bibliometrics with the depth of interpretive analysis. On the one hand, the bibliometric analysis was conducive to identifying the research streams that populate the scientific debate (Frerichs & Teichert, Reference Frerichs and Teichert2021). On the other hand, the interpretive review allowed us to accomplish a thorough investigation of the key topics addressed within and across the streams, envisioning avenues for further developments (Bahoo, Alon, & Paltrinieri, Reference Bahoo, Alon and Paltrinieri2020). To enhance the dependability and the replicability of our study, we stuck to the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR) protocol (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Lim, O'Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). We picked this approach rather than alternative solutions – e.g., Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) – since it is specifically tailored for social sciences (Tsiotsou & Boukis, Reference Tsiotsou and Boukis2022) and facilitated transparency and reliability in crafting and implementing the study design (Kumar, Sahoo, Lim, & Dana, Reference Kumar, Sahoo, Lim and Dana2022). Our approach entails a rigorous and structured protocol, which is based on three steps, namely: (1) assembling; (2) arranging; and (3) assessing.

The first step of the protocol was aimed at identifying the sources and approaches for items' collection and acquisition. Drawing on the arguments presented in the introduction, we framed a tailored search string, which consisted of two parts. The primary keyword focused on the study domain, i.e.: disability management. The secondary keyword concerned the organizational characteristic with which disability management was coupled, i.e.: human resource management. We accounted for different terms which either directly or indirectly referred to human resource management, such as people management and personnel management. This permitted us to be as comprehensive as possible in assembling relevant contributions. When necessary, the asterisk (*) was used to account for any potential variations of the search terms. The primary and secondary keywords were connected through the Boolean operator ‘AND’, whilst the terms composing the secondary keywords were connected through the Boolean operator ‘OR’. The search string used to collect relevant items follows:

((‘Disability manage*’) AND (HR* OR ‘Human resourc*’ OR People OR Personnel OR staff OR employe* OR workforce OR worker* OR laborer*))

Once the search string was elaborated, we launched the documents' acquisition. We performed independent searches on two citation databases, which are largely acknowledged as the most relevant sources to conduct literature reviews, i.e., Elsevier's Scopus® and Clarivate Analytics' Web of Science™ (Liu, Huang, & Wang, Reference Liu, Huang and Wang2021). Other sources, such as Google Scholar, were not contemplated, since they also included preprints and grey literature, which fell outside our purpose of systematizing scientific literature that has been certified by the double-blind review rule (Singh, Singh, Karmakar, Leta, & Mayr, Reference Singh, Singh, Karmakar, Leta and Mayr2021). After several checks, Scopus® was found to deliver the largest number of results. Moreover, items indexed in Web of Science™ were also available in Scopus®. Therefore, we decided to focus on the latter to finalize the acquisition phase. We did not set any temporal limitations to retrieve scientific contributions: all article published within 2021 were contemplated in the analysis. To enhance the replicability of our literature review, we adopted a strict language criterion, admitting only articles published in English. We did not set any further limitations to collect items. Our search was targeted to occurrences in the records' title, abstract, and keywords. As a result, we obtained 403 hits, whose publication year ranged between 1979 and 2021.

The arranging stage followed, involving two steps: the formation of exclusion criteria, and the purification of items which were not consistent with the study aims. A structured approach was taken to enhance the replicability and dependability of items' screening and purification (Kunish, Menz, Bartunek, Cardinal, & Denyer, Reference Kunish, Menz, Bartunek, Cardinal and Denyer2018; Snyder, Reference Snyder2019). This permitted us to effectively coordinate the activities of the authors who were concomitantly involved in arranging the documents and enabled a thorough screening of collected contributions, adding to the comprehensiveness of this literature review. All records were reported in an electronic worksheet. They were coded by title, source type, publication year, keywords, and scientific domain. The authors agreed on three exclusion criteria, which guided the preliminary screening of the dataset. First, items which did not address disability management as an organizational characteristic, but primarily conceived it as a clinical management of health conditions were rejected as off-topic. Second, records which did not highlight the mutual relationship between disability management and human resource management practices were discarded as off-scope. Lastly, manuscripts which included perspectives and commentaries about disability management, or reported a high-level analysis of the sources of risks for employees, without providing compelling evidence on how to improve disabled people's work conditions were retracted as off-focus. The items were screened by three authors, who strictly adhered to the exclusion criteria reported above. The majority rule was adopted to set disagreements. As a result, 295 contributions were removed. More specifically, 85 contributions were off-topic, 116 were off-scope, and 94 were off-focus. Altogether, 108 items were admitted to the final stage of this literature review, which consisted of the assessing stage.

A mixed approach was taken to assess the items. We run a bibliometric analysis to identify research streams linking together the documents included in our refined dataset. We used the VOSviewer software (vers. 1.6.10) to realize this analysis. Bibliographic coupling was applied as the aggregation mechanism. We obtained structural images of research streams (Zupic & Čater, Reference Zupic and Čater2015), which were rooted in the shared research interest calculated from the similarity of reference lists of bibliographically coupled documents (Satish, Pandey, & Arunima, Reference Satish, Pandey and Arunima2020). Drawing on Van Eck and Waltman (Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010), our approach relied on the visualization of similarity technique to display the clusters. VOSviewer creates a similarity matrix based on the normalization of references' co-occurrence, which represents the basis of clusterization (Boyack & Klavans, Reference Boyack and Klavans2010). We defined a threshold of 10 common references for bibliographic coupling, whilst the total citation link strength was set at 5. These criteria led us to identify 91 tightly connected items, which were gathered in 6 clusters. Next, we implemented an interpretive analysis of the documents included in the clusters. We used an inductive approach to classify the records and make sense of them. An individual analysis was followed by a meeting, during which the authors' outputs were carefully reviewed and discussed. The meeting enabled us to obtain a consensus on the clusters' interpretation, which was reported through a narrative approach. Finally, an analysis of the 100 most recurring keywords permitted us to illuminate promising avenues for further developments. Figure 1 reports a flow diagram representing the articulation of this literature review in the three steps described above.

Figure 1. A graphical representation of the process of items' collection and analysis.

Results

An overview of the research streams contemplated in this literature review

Our literature review covered a 30 years' time span, ranging from 1992 to 2021. Altogether, 5 items were published in the concluding decade of the past century (5.5%), whilst about 1 in 3 contributions were published during the first decade of the 21st Century (30.8%) and more than half were accepted for publication after 2015 (50.5%). These figures certify the increasing scholarly attention paid to the interplay of disability management and human resource management to enhance workplace inclusiveness. Articles published in peer-reviewed journals represented most of the dataset (86.8%), followed by book's chapters (11%) and conference proceedings (2.2%). Review papers covered a small portion of items involved in this research (5.1%). It is worth noting that none of them overlapped with the purpose of this study, as they focused on organizational communication for disability prevention, workplace disability management programs, and workplace interventions to foster return to work. On average, reviewed contributions were cited 11 times (σ = 17) at the time of this research, ranging from a minimum of 0 citations to a maximum of 100 citations.

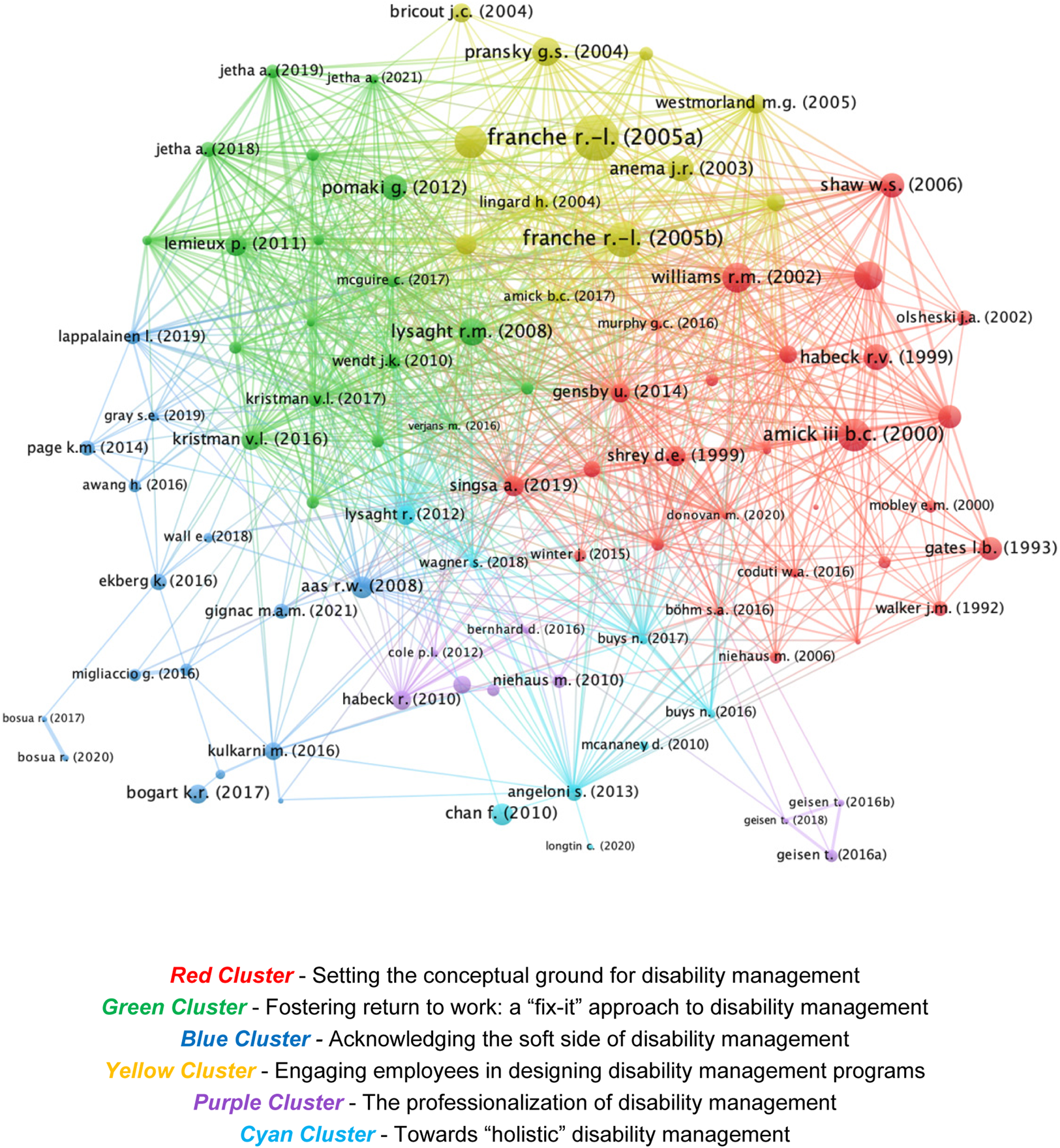

Figure 2 graphically depicts the clusters identified from bibliographic coupling. They embed distinctive research streams that characterize the scholarly debate investigating the interplay of disability management and human resource management. The articulation of the clusters follows a logical flow. The red cluster includes 27 papers and sets the ground for making sense of the transition from a biomedical to an inclusive model of disability management. It emphasizes the orientation towards organizational efficiency of conventional disability management practices and contaminates them with a socio-emotional perspective to foster the shift towards people-centeredness. The green cluster consists of 19 records and focuses on the biomedical shade of disability management, whose priority are retrieved in the preservation and recovery of employees' work ability. The ‘fix it’ understanding of disability management is quarrelled and integrated by the blue cluster, which encompasses 16 records and addresses the soft side of human resource management issues related to disability management. More specifically, the blue cluster highlights the importance of the emotional and affective ingredients of the recipe for workplace inclusiveness.

Figure 2. The visualization of the clustered items.

The yellow cluster gathers 12 contributions: moving from the insights delivered by the blue cluster, it proposes a reconfiguration of disability management according to a participatory perspective, engaging people in the design of human resource management practices aimed at advancing workplace inclusiveness. The purple cluster is composed of 9 records and unfolds an integrated approach to disability management, arguing the shift towards professionalization to accomplish a participatory perspective in designing and implementing disability management initiatives. Lastly, the cyan cluster includes 8 papers and delivers future perspectives on the interplay between human resource management and disability management, paving the way for their holistic integration for workplace inclusiveness. In the following lines, an overview of the research streams is delivered, followed by an integrative discussion which summarizes the state of the art and envisions avenues for further developments.

Setting the conceptual ground for disability management: insights from the red cluster

Disability management has been traditionally understood as a province of occupational health and safety (Gensby et al., Reference Gensby, Labriola, Irvin, Amick and Lund2014), being predominantly focused on minimizing risks of injury and delivering timely rehabilitation services to employees (Habeck, Hunt, & VanTol, Reference Habeck, Hunt and VanTol1998). Embracing this perspective, disability management emerges from a partnership between managers and health professionals: it is targeted at avoiding unnecessary lost time, facilitating timely return to work, and minimizing direct and indirect costs generated by work-related injuries, thus contributing to the enhancement of organizational efficiency (Shrey & Hursh, Reference Shrey and Hursh2009).

The priority given to such concerns ushers a biomedical approach to disability management, which exploits advanced medical knowledge and competences to curb the organizational costs of disability (Mobley, Linz, Shukla, Breslin, & Deng, Reference Mobley, Linz, Shukla, Breslin and Deng2000). Even though it concurs to advancing organizational efficiency, such reductionist interpretation of disability management presents major flaws, which are associated with the depersonalization and desensitization of risk prevention and health promotion initiatives, as well as with side effects on employees' motivation and commitment (Winter, Issa, Quaigrain, Dick, & Regehr, Reference Winter, Issa, Quaigrain, Dick and Regehr2019). Focusing on biomedical issues and putting in the background the social and relational attributes of disability management nourish learned helplessness, which prevents people from getting advantage of policies and processes aimed at achieving inclusiveness (Walker, Reference Walker1992). The biomedical approach neglects human resource management practices and overlooks the critical role of social support and interpersonal trust, which are essential to boost the acceptability of disability management (Murphy & O'Hare, Reference Murphy, O'Hare, Geisen and Harder2016; Randall & Buys, Reference Randall, Buys, Geisen and Harder2016) and stimulate the employees' willingness to participate in risk prevention and health promotion activities (Singsa, Sriyakul, Sutduean, & Jermsittiparsert, Reference Singsa, Sriyakul, Sutduean and Jermsittiparsert2019).

These arguments call us to enrich the conventional biomedical approach to disability management, contaminating it with a human resource orientation. Combining disability management and human resource management sets the conditions for the establishment of a supportive work environment, which empowers people and enables them to overcome the constraints related to disability (Coduti et al., Reference Coduti, Anderson, Lui, Lui, Rosenthal, Hursh and Ra2016). For this to happen, disability management is understood as a shade of diversity management, which specifically contributes to the enactment of workplace inclusiveness for people with disability (Böhm, Dwertmann, & Baumgärtner, Reference Böhm, Dwertmann, Baumgärtner and Geisen2011). Incorporating disability management in the family of diversity management sustains the organizational awareness of the challenges related to reducing risks and improving work conditions of disabled individuals through proactive policies and tailored practices aimed at establishing a fair and inclusive workplace (Harder, Mchugh, Wagner, & Harder, Reference Harder, Mchugh, Wagner and Harder2006). Far from being exclusively directed at minimizing organizational risk factors and coping with disability generated by work conditions, inclusiveness is conceived of as the key focus of disability management (Bruyère, Brown, & Mank, Reference Bruyère, Brown and Mank1997). From this standpoint, disability management programs should include a special concern for accommodating working conditions to the specific occupational and psychosocial needs of people living with disability (Olsheski, Rosenthal, & Hamilton, Reference Olsheski, Rosenthal and Hamilton2002). Besides, transparent, fair, and empathetic communication of organizational initiatives undertaken to overcome work-related constraints caused by disability are necessitated, engaging people in disability management practices and empowering them to flourish at work (Shaw, Robertson, Pransky, & McLellan, Reference Shaw, Robertson, Pransky and McLellan2003).

Embracing a human resource management perspective, the transition from a biomedical to an inclusiveness-oriented model of disability management requires the design and the implementation of participatory practices, which are intended to actively involve people in creating a healthy and supportive workplace (Gensby & Husted, Reference Gensby and Husted2013). Empowering and engaging employees in dealing with the challenges related to disability management has multiple advantages (Niehaus & Bernhard, Reference Niehaus and Bernhard2006). First, it boosts positive sensation with the proximal work environment, enacting a healthy climate in the workplace (Donovan, Khan, & Johnston, Reference Donovan, Khan and Johnston2020). This is conducive to better results in terms of risk prevention, return to work, and well-being (McHugh, Reference McHugh2020; Williams & Westmorland, Reference Williams and Westmorland2002). Second, it constructs a better understanding of the socio-technical context within which disability management programs are crafted and implemented, adding to their effectiveness (Westmorland & Buys, Reference Westmorland and Buys2004). Third, it enhances the quality of the work environment leveraging supportiveness, collaboration, and accountability (Caveen, Dewa, & Goering, Reference Caveen, Dewa and Goering2007). Lastly, it reduces the incidence of avoidable costs, generating a widespread commitment to disability management initiatives and contributing to organizational viability (Salkever, Goldman, Purushothaman, & Shinogle, Reference Salkever, Goldman, Purushothaman and Shinogle2000).

The impact of disability management on inclusiveness is augmented by a people-oriented culture inspiring organizational processes and practices (Amick et al., Reference Amick, Habeck, Hunt, Fossel, Chapin, Keller and Katz2000). Tailored training processes delivered to managers who are involved in handling issues related to well-being in the workplace are essential to underpin such culture and enhance the effectiveness of disability management (Shaw, Robertson, McLellan, Verma, & Pransky, Reference Shaw, Robertson, McLellan, Verma and Pransky2006). On the one hand, it improves the organizational awareness of solutions available to accommodate work conditions of people living with disability and meet their special needs (Gates, Reference Gates1993). On the other hand, it augments the managers' confidence and readiness to promptly address the demands of disabled employees, boosting their capability to contribute to organizational success (McClellan, Pransky, & Shaw, Reference McClellan, Pransky and Shaw2001).

Fostering return to work: a ‘fix-it’ approach to disability management in the green cluster

Adopting a sheer biomedical interpretation, most disability management policies and programs are concerned with recovering and/or preserving the employees' work ability. They are aimed at tackling risk factors which trigger disability or overcoming the organizational and management barriers preventing the timely return to work of people who got injured (Kristman, Shaw, C., Delclos, Sullivan, & Ehrhart, Reference Kristman, Shaw, C., Delclos, Sullivan and Ehrhart2016). Embracing this perspective, the design of disability management initiatives has been argued to rely on a four-steps process, consisting of: (1) the analysis of the context of implementation, (2) the planning of risk prevention and health recovery initiatives, (3) the implementation of planned initiatives, and (4) the continuous support delivered to employees and managers to fix shortcomings and enhance work conditions (Main, Nicholas, Shaw, Tetrick, Ehrhart, & Pransky, Reference Main, Nicholas, Shaw, Tetrick, Ehrhart and Pransky2016). Consistently with these arguments, rate of absenteeism and timeliness of the return to work have been conventionally used as the key indicators to assess the quality and effectiveness of disability management practices (Wendt, Tsai, Bhojani, & Cameron, Reference Wendt, Tsai, Bhojani and Cameron2010).

Maintaining the work ability of people with disabilities has been usually approached emphasizing the technical side of disability management, which concentrates on the structural characteristics of the workplace and emphasizes the need for adapting the work environment to the reduced capabilities of people with disability (Jakobsen & Svendsen, Reference Jakobsen and Svendsen2013). Accommodation is a specialistic task accomplished by supervisors with the collaboration of health specialists, who coordinate the whole process of work reintegration (Bohatko-Naismith, James, Guest, Rivett, & Ashby, Reference Bohatko-Naismith, James, Guest, Rivett and Ashby2019) and provide employees with increased margins of manoeuvre to find an alignment with the work environment (O'Hagan, Reference O'Hagan2019). The success of biomedical-oriented disability management programs has been associated with two factors: the supervisors' autonomy in crafting interventions to address the needs and conditions of disabled people (Kristman, Shaw, Reguly, Williams-Whitt, Soklaridis, & Loisel, Reference Kristman, Shaw, Reguly, Williams-Whitt, Soklaridis and Loisel2017), and the supervisors' involvement in advanced training activities which boost the acknowledgement of organizational policies and practices facilitating the integration of employees with disability in organizational dynamics (Nastasia, Coutu, Rives, Dubé, Gaspard, & Quilicot, Reference Nastasia, Coutu, Rives, Dubé, Gaspard and Quilicot2021).

As previously anticipated, the primacy of the technical side is inconsistent with the complexity of disability management, which should be designed and implemented stressing the social components of work (Jetha, Yanar, Lay, & Mustard, Reference Jetha, Yanar, Lay and Mustard2019). Balancing the technical and the social sides of disability management acknowledges that the work ability of people living with disability does not exclusively rely on the structural characteristics of the work setting. It is concomitantly affected by the employees' emotional attributes and the relational features of the work integration process (Lemieux, Durand, & Hong, Reference Lemieux, Durand and Hong2011). From this standpoint, return to work represents only a nuance of disability management, which is also concerned with advancing the psycho-physical well-being of people and tackling social exclusion (Verjans, Rommel, Tijtgat, & Bruyninx, Reference Verjans, Rommel, Tijtgat, Bruyninx, Geisen and Harder2011). This makes people able to express their full contribution to organizational performance, regardless of their disability (Pomaki, Franche, Murray, Khushrushahi, & Lampinen, Reference Pomaki, Franche, Murray, Khushrushahi and Lampinen2012).

Acknowledging the need for harmonizing the technical and the social features of disability management permits us to identify some additional factors which are conducive to the successful work reintegration. Employees' awareness of disability management initiatives and perception of mutual trust in the workplace are crucial to improve return to work (Lysaght & Larmour-Trodeb, Reference Lysaght and Larmour-Trodeb2008). Both supervisors' positivity and co-workers' support are required for this purpose, enacting an organizational climate which empowers people with disability and facilitate their work reintegration (Dunstan, Mortelmans, Tjulin, & MacEachen, Reference Dunstan, Mortelmans, Tjulin and MacEachen2015; Jetha, LaMontagne, Lilley, Hogg-Johnson, Sim, & Smith, Reference Jetha, LaMontagne, Lilley, Hogg-Johnson, Sim and Smith2018). Employees' engagement in crafting and implementing disability management initiatives is argued to contribute to the effectiveness of work return, making people co-responsible of the process and paving the way for a personalization of organizational policies and practices to tackle disability (McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Kristman, Shaw, Loisel, Reguly, Williams-Whitt and Soklaridis2017). However, an effort should be made to escape the side effects triggered by engagement. In fact, if the organization is unable to fully realize the employees' active participation within the design of disability management practices, engagement might undermine individual commitment (Maiwald, Meershoek, De Rijk, & Nijhuis, Reference Maiwald, Meershoek, De Rijk and Nijhuis2013). Empathic communication is necessitated to empower people experiencing disability and foster their involvement in shaping disability management policies and practices (Jetha, Le Pouésard, Mustard, Backman, & Gignac, Reference Jetha, Le Pouésard, Mustard, Backman and Gignac2021). Information and communication technologies should be used for this purpose, making communication timely and promoting the employees' access to information needed to get advantage of disability management programs (Singh & O'Hagan, Reference Singh and O'Hagan2019).

Acknowledging the soft side of disability management: new perspectives from the blue cluster

As previously anticipated, the emphasis attached to occupational health services in the implementation of disability management and the focus on the technical side of work integration postulate a universalistic approach to addressing the work-related needs of people with disability, leaving in the background the emotional and affective work experiences of disabled people (Lappalainen, Liira, Lamminpää, & Rokkanen, Reference Lappalainen, Liira, Lamminpää and Rokkanen2019). Whilst this approach facilitates return to work, it falls short in highlighting the contextual and cultural specificities of disability management (Kulkarni, Boehm, & Basu, Reference Kulkarni, Boehm and Basu2016). This generates backlash in the form of lack of support in the workplace, unbearable effort intensification, and feelings of job insecurity (Ekberg et al., Reference Ekberg, Pransky, Besen, Fassier, Feuerstein, Munir and Blanck2016). Such shortcomings are exacerbated by the limited organizational capability to craft human resource management practices which are consistent with the distinguishing demands of disabled employees (Migliaccio, Reference Migliaccio2019). The propensity to judge disability as a management problem, the cultural intolerance towards disability, and the poor knowledge, skills, and attitudes developed by supervisors in dealing with disability (Botha & Leah, Reference Botha and Leah2020; Gignac et al., Reference Gignac, Bowring, A., Beaton, Breslin, Franche and Saunders2021) make it difficult to devise flexible and nonstandard work arrangements for disabled employees (Bosua & Gloet, Reference Bosua and Gloet2021a, Reference Bosua, Gloet, Blount and Gloet2021b).

The soft – emotional and affective – side of disability management should be vigilantly managed to overcome these problems and enhance the involvement of disabled people in organizational dynamics, avoiding that job demands translate into inadequate control over work and impaired ability to function in the workplace (Wall & Selander, Reference Wall and Selander2018). Supervisors play a key role for this purpose, establishing a fair and transparent contact with disabled employees and enabling them to cope with the organizational barriers through considerable relationships and empathy (Aas, Ellingsen, Lindøe, & Möller, Reference Aas, Ellingsen, Lindøe and Möller2008). Supervisors are in a critical position to illuminate the soft aspects of disability, preventing that fear of stigma might undermine the implications of disability management policies and practices on the process of work integration (Bogart, Rottenstein, Lund, & Bouchard, Reference Bogart, Rottenstein, Lund and Bouchard2017).

The scholarly debate identified several factors empowering supervisors to elicit the soft side of disability management and handle it to advance workplace inclusiveness. The adoption of an open approach based on collaboration and engagement is a requisite to stimulate people to make explicit the tacit challenges that affect the design and implementation of human resource management practices addressing disability-related issues (Awang, Shahabudin, & Mansor, Reference Awang, Shahabudin and Mansor2016). Moreover, disability management interventions should be twofold, including both an instrumental component intended to facilitate the accommodation of the work environment to the needs of disabled people, and an emotional component, which recognizes and unleashes the motivational triggers of disabled individuals (Gray, Sheehan, Lane, Jetha, & Collie, Reference Gray, Sheehan, Lane, Jetha and Collie2019). To facilitate the combination of the instrumental and the emotional components of disability management, people living with disability should participate in motivational interviews when crafting disability management practices, which permit supervisors to enlighten the soft side of disability and take actions to deal with it (Page & Tchernitskaia, Reference Page and Tchernitskaia2014). The implications of disability management are deeply affected by the effects of work integration on work-life balance (Migliaccio, Reference Migliaccio2016). Digitalization should be exploited to support people with disabilities in handling the interplay between work concerns and personal life, without experiencing role conflict. This fosters work inclusiveness and meets the purpose of disability management to promote work engagement (Luu, Reference Luu2022).

Engaging employees in disability management programs: the yellow cluster's contribution

Previous research stressed that the design of policies and practices targeted at work integration of disabled employees sustains organizational inclusiveness (Amick et al., Reference Amick, Lee, Hogg-Johnson, Katz, Brouwer, Franche and Bültmann2017), promoting the modification of workplaces to accommodate individual and collective work-related demands (Cullen et al., Reference Cullen, Irvin, Collie, Clay, Gensby, Jennings and Amick2018). However, critical concerns have been raised about the authoritative and unidirectional approach characterizing most disability management programs (Pransky, Shaw, Franche, & Clarke, Reference Pransky, Shaw, Franche and Clarke2004), which impoverishes their effectiveness in terms of employees' well-being and active involvement at work (Franche et al., Reference Franche, Cullen, Clarke, Irvin, Sinclair, Frank and Van Eerd2005b). The perceived institutional unavoidability of these shortcomings leads companies to consider disability management as a cost, which does not bring clear organizational advantages (Lingard & Saunders, Reference Lingard and Saunders2004).

Even though cultural, organizational, and technical problems hinder the employees' participation in the design and implementation of disability management (Anema, Steenstra, Urlings, Bongers, De Vroome, & Van Mechelen, Reference Anema, Steenstra, Urlings, Bongers, De Vroome and Van Mechelen2003), the shift towards a person-centred approach is a feasible solution to overcome the disadvantages attached to the traditional fix-it interpretation of disability management (Williams-Whitt, Bültmann, Amick, Munir, Tveito, & Anema, Reference Williams-Whitt, Bültmann, Amick, Munir, Tveito and Anema2016). The adoption of a participatory approach to disability management discloses multiple advantages, such as: (1) the active involvement of disabled employees in goal setting, which is crucial to set achievable targets and commit people to organizational inclusiveness (Westmorland, Williams, Amick, Shannon, & Rasheed, Reference Westmorland, Williams, Amick, Shannon and Rasheed2005); (2) the increased capability to spot paradigm dissonance and potential sources of conflict among actors involved in the implementation of disability management programs (Franche, Baril, Shaw, Nicholas, & Loisel, Reference Franche, Baril, Shaw, Nicholas and Loisel2005a); (3) the improvement of the health and safety climate perceived by employees, which determines better outcomes in terms of inclusiveness (Williams, Westmorland, Shannon, Farah Rasheed, & Amick, Reference Williams, Westmorland, Shannon, Farah Rasheed and Amick2005); (4) the empowerment of people to recommend modification of work settings and job assignments which are not consistent with their work ability (Busse et al., Reference Busse, Dolinschi, Clarke, Scott, Hogg-Johnson, Amick and Cole2011); and (5) the enhancement of the individual willingness to embark on organizational initiatives promoting workplace inclusiveness (Bricout, Reference Bricout2004).

Professionalizing disability management: the cues included in the purple cluster

The fix-it interpretation locates disability management outside of human resource management practices and hugely rely on the managers' readiness to acknowledge the special needs of people with disability (Paez & Arendt, Reference Paez and Arendt2014). The shift towards a people-centred perspective involves the adoption of an integrated approach, which is directed at achieving a fully-fledged job-person fit, rather than merely accommodating the work environment to the job demands of people living with disability (Habeck, Hunt, Rachel, Kregel, & Chan, Reference Habeck, Hunt, Rachel, Kregel and Chan2010). The integration of disability management and human resource management is nurtured by the evolving socio-demographic context which is faced by modern companies. Inter alia, workforce ageing makes proactive disability management an organizational priority to achieve resilience and excellence (Bruyère, Reference Bruyère2006).

For this to happen, a professionalization of disability management is sought for. It is eventually intended to make organizations ready to undertake major workplace changes, promoting the employees' empowerment and encouraging their active participation in establishing a healthy and supportive work environment (Bernhard, Niehaus, & Marfels, Reference Bernhard, Niehaus, Marfels, Geisen and Harder2016). In this context, disability management serves two main functions (Geisen, Reference Geisen, Geisen and Harder2016). Embracing a preventive perspective, it is directed at protecting and promoting the ability of disabled people to contribute to organizational success, tackling any sources of risk which may compromise their well-being at work (Geisen, Reference Geisen and MacEachem2018). Embracing a pragmatic perspective, it delivers continuous assistance to employees with disability, providing them with physical, technical, social, and psychological support to address flaws generated by disability (Geisen, Lichtenauer, Roulin, & Schielke, Reference Geisen, Lichtenauer, Roulin, Schielke, Geisen and Harder2016).

From this point of view, two sets of professional competencies have been argued to set the conditions for successful disability management. Establishing fair, transparent, and collaborative relationships with people who are targeted by disability management represents the key competence in disability management. It should be coupled with human resource management expertise, which entails the capability to develop policies, procedures, and guidelines prompting an integrated approach to work reintegration (Niehaus & Marfels, Reference Niehaus and Marfels2010). Such competencies enable managers to take advantage of disability management initiatives to protect and promote the well-being of disabled employees, nourishing morale and sustaining organizational performances (Cole, Cecka, & Smith, Reference Cole, Cecka and Smith2012).

Towards ‘holistic’ disability management: the way forward embedded in the cyan cluster

The shift towards an inclusiveness-oriented perspective in the design and implementation of disability management brings with itself two implications. On the one hand, it gives emphasis to the demand side of disability management, shedding light on disabled employees' specific needs and heralding a transversal organizational effort to ensure safe and decent work conditions (Chan, Strauser, Gervey, & Lee, Reference Chan, Strauser, Gervey and Lee2010). On the other hand, it implies an integration of disability management with other organizational domains, including human resource management (Angeloni, Reference Angeloni2013). However, legacy issues and process obstacles tie organizations to conventional approaches to disability management, which stick to the biomedical perspective and are primarily intended to aid disabled employees' recovery and return to work (McAnaney & Williams, Reference McAnaney and Williams2010).

Embracing a holistic understanding of disability management entails acknowledging it as an integral part of organizational policies and practices. This involves appreciating its distinctive contribution to improving individual and collective performances, which are boosted by an empowering work environment based on positive interpersonal relationships (Lysaght, Fabrigar, Larmour-Trode, Stewart, & Friesen, Reference Lysaght, Fabrigar, Larmour-Trode, Stewart and Friesen2012). Literature argued the existence of a reciprocal link between disability management and organizational culture (Buys et al., Reference Buys, Wagner, Randall, Harder, Geisen, Yu and Fraess-Phillips2017). Effective disability management is rooted in organizational cultures whose symbols, artefacts, and values espouse a genuine support to people living with disability, enacting a work climate which is conducive to inclusiveness (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Buys, Yu, Geisen, Harder, Randall and Howe2018). At the same time, the design of tailored disability management programs consolidates a positive organizational culture, which generates high morale and increases job satisfaction (Buys et al., Reference Buys, Wagner, Randall, Yu, Geisen, Harder and Howe2016). Alongside promoting positive work conditions, this is expected to augment individual self-efficacy to deal with disability-related issues, encouraging people to participate in co-planning and co-implementing initiatives aimed at workplace inclusiveness (Longtin, Tousignant-Laflamme, & Coutu, Reference Longtin, Tousignant-Laflamme and Coutu2020).

A systematization of disability management perspectives and initiatives

Figure 3 combines the clusters obtained from bibliographic analysis in an integrative framework, enabling us to deliver a comprehensive account of the results of this literature review. Four dimensions have been used to make sense of the interplay between disability management and human resource management. First, attention is paid to the scope of disability management, which varies across a continuum ranging from work reintegration to the socio-emotional work engagement of disabled people. Second, a focus is put on the approach taken to accomplish disability management: universalism entails a homogeneous and standardized approach, whilst a personalized view assumes that disability management practices should be targeted to the special health and social needs of people suffering from disability, curbing job demands and advancing job resources. Third, the perspective taken in addressing disability management is examined. It can either embrace a biomedical focus, sticking to a fix-it perspective, or adopt an inclusiveness-oriented view, which is targeted at empowering people living with disability. Lastly, the managerial focus undertaken to arrange disability management practices is investigated. An organization-centred perspective directed at enhancing efficiency and effectiveness is contrasted with a people-centred approach, which envisages a fully-fledged interplay between disability management and human resource management.

Figure 3. A systematization of disability management policies and practices.

The fix-it approach embedded in the green cluster is directed at fostering disabled employees' work reintegration. It enacts a universalistic approach, which is driven by a managerial focus centred on organizational dynamics. A biomedical perspective is taken, which intends to remove the sources of disability and/or create accommodations to facilitate return to work of people with disability. The blue cluster expands the scope of disability management, combining work reintegration with the socio-emotional engagement of employees. Whilst a universalistic approach is maintained, an inclusiveness-oriented perspective contaminates the biomedical view, emphasizing the soft-side of disability management. The yellow cluster highlights employees' engagement and postulates a shift towards work inclusiveness, which is endorsed over the biomedical perspective: it ushers a transition towards a personalized model of disability management, which is centred on people, rather than on the organization. The purple cluster puts this evolution at the service of work reintegration, enriching the biomedical perspective with a concern for people-centeredness and a personalized approach to disability management in order to accomplish job-person fit. This calls for a professionalization of disability management, which turns out to be a particular shade of diversity management. The cyan cluster epitomizes the transition towards people-centeredness and personalization, stressing the need for engaging disabled employees at work and achieving a fully-fledged work inclusiveness. In sum, a ‘holistic’ disability management approach underlies the cyan cluster, according to which a full integration with human resource management practices is sought for. The red cluster accounts for the gradual transition from a ‘fix-it’ approach to a ‘holistic’ view of disability management, which is inclusive-oriented and aims at empowering people with disability.

Discussion

The evolving interplay between disability management and human resource management

The interplay of disability management and human resource management underwent different stages, which are graphically depicted in Figure 4. During the early stage, disability management has been conceived of as a province of occupational health and safety, being detached from the design and implementation of human resource management. A reductionist perspective characterized the original conceptualization of disability management, whose focus was on tackling disability produced by organizational sources of physical and psycho-social stress, facilitating the work integration of disabled employees. Disability is dealt with as a disturbance factor constraining individual and collective performance and undermining organizational viability. Embracing a biomedical perspective, disability is addressed through corrective initiatives: the main target is restoring the employees' capability to contribute to organizational success, absorbing the negative implications of disability on work abilities. Human resource management practices ensue the implementation of disability management policies, with the purpose of finding an accommodation between the needs of disabled people and the characteristics of the work environment.

Figure 4. The interplay between disability management and human resource management.

The expansion of the organizational concern to preventive measures can be retrieved in the second stage. Far from focusing on the treatment of physical and psycho-social problems experienced by disabled employees, disability management includes a focus on preventing flaws in the individual and collective well-being at work. A partial overlapping of human resource management and disability management can be envisioned. Organizational policies and practices intended to enhance the work conditions of people with disability include training sessions delivered to employees and supervisors to enhance their readiness to cope with the sources of physical and psycho-social stress in the workplace. Furthermore, attention is paid to the recruitment and retention of disabled employees, putting into practice an organizational action directed towards work integration. Lastly, adaptations of work design and performance assessment are introduced to account for the specific contribution to organizational success of people living with disability and overcome their job-person misfits.

The third stage heralds the transition into an inclusive-oriented approach to disability management. Building an inclusive organization, which is aware of the special work and nonwork-related needs of disabled people, is acknowledged as a distinctive trait of resilient organizations. Embedding disability management in the organizational culture facilitates its joint optimization with human resource management. Rather than being handled as a sheer nuance of diversity management, the concern for disability permeates the design and the implementation of human resource management practices, which aim at establishing a healthy and empowering workplace. Going beyond the prevention-treatment dichotomy, a holistic approach to disability management emerges, which solicits organizations to recognize the work-related challenges generated by disability. Both precautionary and proactive actions are undertaken to prevent that stigma and discrimination might impair the capability of people with disability to flourish at work.

A reconfiguration of the scope of disability management ensues from this evolution. In the first stage, an organization-centred focus prevails. The purpose of disability management is to foster the return to work of people with disability, minimizing absenteeism and contributing to organizational productivity. An organization-centred perspective is preserved in the second stage, where the main objective of disability management practices is to achieve and sustain a job-person fit which lessens the physical and psycho-social risks experienced by disabled employees in the workplace and attempts to avoid problems for organizational performance triggered by a deterioration of individual health-related conditions. A shift towards employee-centeredness is associated with the third stage. The purpose of disability management policies is to empower people, enabling them to thrive at work and actively participate in framing and implementing interventions to deal with disability in the workplace.

Figure 5 graphically displays the interplay between disability management and human resource management, using a matrix which is articulated along two dimensions. On the one hand, the intertwinement between disability management and human resource management is contemplated, ranging from disintegration to joint optimization. On the other hand, the organizational priority attached to disability management policies is reported, ranging from work integration to organizational inclusiveness. For each quadrant of the matrix, the interplay between disability management and human resource management is portrayed. The lower area of the matrix focuses on the traditional interpretation of disability management, which predominantly aims at handling disability as a disturbance factor. Stage 1 is characterized by a disintegration of disability management and human resource management. The priority is on buffering disability, preserving and/or recovering the work ability of people who suffer from physical and/or mental flaws. Stage 2 evolves towards a joint optimization of disability management and human resource management. However, maintaining the focus on work integration constrains such interplay. It forces an alignment of disability management and human resource management, which are aimed at reducing work-related risks and reintegrating people who suffer from disability in the workplace. Stage 3 occupies the upper part on the matrix, entailing an orientation towards inclusiveness. In the left quadrant, a disintegration between disability management and human resource management emerges. In the right quadrant, a fully-fledged joint optimization of disability management and human resource management accompanies the focus on workplace inclusiveness. A holistic model arises, which is directed at involving people with disability in organizational dynamics, advancing their ability to contribute to organizational excellence.

Figure 5. The interplay between disability management and human resource management.

Research limitations and avenues for further development

The study findings should be read acknowledging the limitations which affected this literature review. First, Elsevier's Scopus® was used as the sole source for collecting items. Although this decision constrained the breadth of our research, it did not negatively affect the consistency and dependability of the study findings, since the queried database permitted us to have a comprehensive overview of the state of scientific knowledge about the interplay of disability management and human resource management. Second, the decision to focus our review on the intertwinement between disability management and human resource management was consistent with the study aims, but it reduced the width of our research, overlooking how disability management relates with other areas of managerial concern. Third, using an interpretive approach to delve into the research clusters might have produced subjective biases in presenting the streams populating the current scholarly debate. However, the robustness of the protocol used for conducting this literature review ensures us of the study replicability, adding to the dependability of the research findings. Last, we adopted a macro-level perspective in reviewing the scientific literature. Rather than zooming in on specific organizational and management practices, we addressed the strategic interplay between disability management and human resource management, highlighting the increasing emphasis attached to workplace inclusiveness.

Further research is required to push forward what we know about the interpretation of disability management as a distinctive area of organizational focus and its relationship with human resource management to accomplish workplace inclusiveness. Insights about avenues for further developments can be retrieved in Figure 6, which graphically displays the 100 most recurring keywords listed by the reviewed documents. Three main avenues for future development can be envisaged. There is limited agreement about what are the implications of disability management on job-person fit. As depicted by the keywords highlighted in blue and purple, most scholarly attention has been addressed to the hard/tangible side of disability management. Conversely, the soft and intangible issues of disabled employees' work experiences have been overlooked. The contextualization of the self at work is essential to achieve a job-person fit. In fact, self-determination at work is significantly affected by psycho-social factors. Therefore, a twofold concern for hard and soft issues should be embedded in optimizing disability management and human resource management, achieving a factual job-person fit.

Figure 6. Envisioning avenues for further development from keywords' analysis.

Drawing on the keywords spotted in green, additional research is needed to illuminate how disability management can be coupled with human resource management to achieve organizational inclusiveness. A focus on return to work characterized most scholarly research on this topic. Being constrained by a reductionist interpretation, such a focus prevents us from fully recognizing how disability management and human resource management are intertwined. Embracing a holistic approach, attention should be paid to organizational strategies and initiatives which are aimed at integrating disability management and human resource management in a conjoint effort to enact a healthy and empowering workplace.

Lastly, as witnessed by the keywords in yellow, further research should be targeted to unveil how human resource management practices can be exploited to engage people in the co-production of disability management. Co-production makes personalization of disability management possible and paves the way for tailored organizational interventions aimed at building an inclusive workplace, which is consistent with the evolving demands of the workforce. This is expected to minimize the risk that disability is handled as a disturbance factor or, at best, that disability management interventions serve as window dressing tools to achieve institutional legitimacy and social acceptability. Furthermore, it augments the implications of disability management on the organizational capability to build an attractive and empowering work environment, coherently with the work-related expectations of millennials who enter the labour market.

Conclusions

Drawing on the study results, it is possible to argue a tentative answer to the questions which inspired this literature review. Research investigating the interplay between disability management and human resource management can be articulated in two polarized streams. On the one hand, a reductionist view conceives disability management as a specialized area of organizational action falling within occupational health and safety services. It is only indirectly related to human resource management and primarily aims at fostering the integration at work of people with disability. On the other hand, a holistic view understands disability management as a core component of a resilient organization, which cares for workplace healthiness and psycho-physical well-being at work. Disability management and human resource management are mutually related, being associated by the purpose of empowering people and enabling them to flourish in the workplace.

Combining disability management and human resource management in a conjoint organizational effort targeted towards inclusiveness is a complex process, which unfolds through three steps. At the beginning, it requires the consolidation of an inclusive organizational culture, which sets the conditions for empowering people and engaging them in building a healthy workplace. Next, it necessitates the arrangement of clear organizational protocols, procedures, and processes which acknowledge the special work-related needs of people living with disability and prevent the occurrence of risks for their psycho-physical well-being at work. Finally, it is rooted in soft interventions exploiting social ties to establish a supportive organizational climate. This permits to avoid stigma triggered by disability and energizes people to contribute to organizational excellence.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.