Tausug (ISO code tsg) is an Austronesian language spoken on the island of Jolo in the southwestern Philippines. It is also found on other nearby islands in the southwestern part of the Philippines and in parts of Sabah, Malaysia, where it is called Suluk. The population of the Tausug in the Philippines is estimated at 900,000 (Gordon Reference Gordon2005) and the year 2000 population estimate of the Suluk in Sabah, Malaysia, is 150,000.Footnote 1 The following description is based on the variety spoken on Jolo. ‘The North Wind and the Sun’ text was translated from English into Tausug by Irene Hassan. Previous studies of Tausug phonology include Asmah (Reference Omar1978, Reference Omar1983) and Hassan, Ashley & Ashley (Reference Hassan, Ashley and Ashley1994). David Lao, age 62 at the time of the recording, born in Jolo, Philippines, was the reader for the Tausug words in this article. Due to difficult access into the language area, all audio recordings were obtained by Skype transmission.

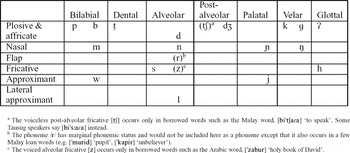

Consonants

Tausug has some examples of consonant gemination at syllable boundaries, e.g. nagkukummus [naɡkuˈkumːus] ‘to cover someone’, and mattan [ˈma![]() ːan] ‘surely, truly’. Also, when the velar consonant becomes a geminate at syllable boundaries, there is free variation as follows: pagga [ˈpaɡɡa] ~ [ˈpaɡka] ‘whereas’.

ːan] ‘surely, truly’. Also, when the velar consonant becomes a geminate at syllable boundaries, there is free variation as follows: pagga [ˈpaɡɡa] ~ [ˈpaɡka] ‘whereas’.

All plosives are unreleased in syllable-final position, e.g. atup [ˈa![]() up˺] ‘roof’, taub [ˈ

up˺] ‘roof’, taub [ˈ![]() aʔub˺] ‘high tide’, langit [ˈlaŋi

aʔub˺] ‘high tide’, langit [ˈlaŋi![]() ˺] ‘sky’, ūd [ʔuːd˺] ‘maggot’, tuktuk [ˈ

˺] ‘sky’, ūd [ʔuːd˺] ‘maggot’, tuktuk [ˈ![]() uk˺

uk˺![]() uk˺] ‘forehead’, balig [ˈbaliɡ˺] ‘crooked’. The voiceless plosives /p/, /t/, and /k/ are unaspirated. The voiced plosives /b/ and /ɡ/ are sometimes realized as non-sibilant fricatives in intervocalic position, e.g. abagah [ʔaˈβaɣah] ~ [ʔaˈβagah] ‘shoulder’, and tubu [ˈ

uk˺] ‘forehead’, balig [ˈbaliɡ˺] ‘crooked’. The voiceless plosives /p/, /t/, and /k/ are unaspirated. The voiced plosives /b/ and /ɡ/ are sometimes realized as non-sibilant fricatives in intervocalic position, e.g. abagah [ʔaˈβaɣah] ~ [ʔaˈβagah] ‘shoulder’, and tubu [ˈ![]() ubu] ~ [ˈ

ubu] ~ [ˈ![]() uβu] ‘sugarcane’. This is often the case between identical vowels. The non-sibilant fricatives were more noticeable with Tausug speakers from remote villages. The voiced plosives were more noticeable with Tausug speakers from urban areas.

uβu] ‘sugarcane’. This is often the case between identical vowels. The non-sibilant fricatives were more noticeable with Tausug speakers from remote villages. The voiced plosives were more noticeable with Tausug speakers from urban areas.

The voiceless affricate [tʃ], as in [biˈtʃaɾa] ‘to speak’, only occurs word medially. Depending on the speaker's isolect, some pronounce this sound as a lengthened sibilant [ss]. Others pronounce it as a stop followed by a sibilant [ts]. But it is most commonly pronounced as a voiceless affricate [tʃ].

The [r]-sound is realized as a flap when it occurs as an allophone of /d/. This phenomenon occurs in the intervocalic position both within single words and across word boundaries. For example, the word ud ‘worm’ becomes [ˈurun] ‘to become infested with worms’. The word dayaw ‘goodness’ becomes [maˈrayaw] ‘to have the quality of goodness’. The phrase duwa di duwa duun ‘two here two there’ becomes [ˈduwari ˈruwa ˈruʔun].

When [r] occurs as a phoneme, not as an allophone of /d/, it is manifested as a flap. There is also some free variation between the [r] and the alveolar lateral approximant [l] (e.g. parman [ˈparman] ~ [ˈpalman] ‘word’, sarta [ˈsar![]() aʔ] ~ [ˈsal

aʔ] ~ [ˈsal![]() aʔ] ‘simultaneously’, sarsila [sarˈsila] ~ [salˈsila] ‘genealogy’). The alveolar flap [r] is more commonly used by urban speakers of Tausug. The alveolar lateral approximant [l] is more commonly used by the village speakers of Tausug. The phoneme /r/ has marginal phonemic status and would not be included here as a phoneme except that it also occurs in a few loan words from Malay (e.g. murid [ˈmurid] ‘pupil, follower’, kapir [ˈkapir] ‘infidel or unbeliever’).

aʔ] ‘simultaneously’, sarsila [sarˈsila] ~ [salˈsila] ‘genealogy’). The alveolar flap [r] is more commonly used by urban speakers of Tausug. The alveolar lateral approximant [l] is more commonly used by the village speakers of Tausug. The phoneme /r/ has marginal phonemic status and would not be included here as a phoneme except that it also occurs in a few loan words from Malay (e.g. murid [ˈmurid] ‘pupil, follower’, kapir [ˈkapir] ‘infidel or unbeliever’).

Vowels

Tausug has three vowel phonemes, /a/, /i/, and /u/. Like other Philippine languages with small vowel systems, /i/ and /u/ in Tausug demonstrate a range in vowel height, e.g. bola [ˈbola] ~ [ˈbula] ‘ball’.

Stress

Stress in Tausug is not phonemic and falls on the penultimate syllable of two syllable words as is shown below.

In three-syllable words, stress again falls primarily on the penultimate syllable except in certain loan words, in which the stress pattern follows the stress pattern of the source language, as in [ˈsaj.an.![]() is] ‘scientist’.

is] ‘scientist’.

There are other cases of exceptions to the penultimate stress rule due to certain affixation and word compounding as is indicated in the transcription of the recorded passage below.

Phonetic transcription of recorded passage

in ˈpasalsin ˈhaŋin ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ ˈiβansin ˈsuga

aɾaʔ ˈiβansin ˈsuga

manˈdʒaɾi | hamˈbuːk ˈadlawnaɡˈ![]() uːkin ˈhaŋin ˈu

uːkin ˈhaŋin ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ ˈiβan ˈsuga | paɡˈki

aɾaʔ ˈiβan ˈsuga | paɡˈki![]() aʔ ˈnilasinhamˈbuːk ˈ

aʔ ˈnilasinhamˈbuːk ˈ![]() aʔumiaˈmanaw | naɡkuˈkummussinhaβulmaˈɾakmul ‖ naɡˈ

aʔumiaˈmanaw | naɡkuˈkummussinhaβulmaˈɾakmul ‖ naɡˈ![]() uːk ˈsilabaŋ hiˈsjuinmakuˈsuɡ haˈɾuwa ˈsila ‖ ˈlaʔuŋ niˈla | hiˈsju-ˈsjuinmakaˈluɡusha ˈ

uːk ˈsilabaŋ hiˈsjuinmakuˈsuɡ haˈɾuwa ˈsila ‖ ˈlaʔuŋ niˈla | hiˈsju-ˈsjuinmakaˈluɡusha ˈ![]() aʔu ˈjaʔunmaɡˈʔiːɡ sin ˈhaβulniˈjamaˈɾakmul | na | ˈsjainmakuˈsuɡ ‖ saˈkalihiˈmujupna

aʔu ˈjaʔunmaɡˈʔiːɡ sin ˈhaβulniˈjamaˈɾakmul | na | ˈsjainmakuˈsuɡ ‖ saˈkalihiˈmujupna

makuˈsuɡ in ˈhaŋin ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ ‖ ˈsaɡawaʔ ˈwalaʔ daiˈniːɡ sin ˈ

aɾaʔ ‖ ˈsaɡawaʔ ˈwalaʔ daiˈniːɡ sin ˈ![]() aʔuˈjaʔunin ˈhaβulniˈja

aʔuˈjaʔunin ˈhaβulniˈja

maˈɾakmul | ˈɡammaˌjan | naɡˈkummusna ˈ![]() uʔudsja | ˈpaɡɡa ˈmaɡkukuˌsuɡ in ˈhaŋin

uʔudsja | ˈpaɡɡa ˈmaɡkukuˌsuɡ in ˈhaŋin

ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ ‖ ˈpaɡɡabiˈhad

aɾaʔ ‖ ˈpaɡɡabiˈhad![]() u | iˈmunduŋ nain ˈhaŋin ˈu

u | iˈmunduŋ nain ˈhaŋin ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ ‖ na | siˈmublinain ˈsuga ‖

aɾaʔ ‖ na | siˈmublinain ˈsuga ‖

paɡˈsilaksin ˈsuɣa | piˈjasuʔ nain ˈ![]() aʔuˈjaʔun | ˈsaɾ

aʔuˈjaʔun | ˈsaɾ![]() aʔ ˈmaɡ

aʔ ˈmaɡ![]() ujniˈjaiˈniːɡ in ˈhaβulniˈja

ujniˈjaiˈniːɡ in ˈhaβulniˈja

maˈɾakmul ‖ ˈhaŋkannaˈŋakunain ˈhaŋin ˈu![]()

![]() aɾaʔ sindiˈjaʔuɡ sja | ˈiβan ˈma

aɾaʔ sindiˈjaʔuɡ sja | ˈiβan ˈma![]()

![]() annasinin ˈsugamakuˈsuɡ dajnˈkanija

annasinin ˈsugamakuˈsuɡ dajnˈkanija

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Steve Parker, Pete Unseth, Scott Youngman and two anonomous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. All errors are our responsibility.