1. Law of treaties

A. Provisional application of treaties

The provisional application of treaties is being used in an increasing number of contexts in Canadian practice.

1. Introduction

Provisional application of treaties is being used in an increasing number of contexts.

In recognition of this trend and the evolving practice of States, the General Assembly adopted resolution 76/113 of 9 December 2021, entitled “Provisional Application of Treaties,” in which the Assembly requested “…the Secretary-General to prepare a volume of the United Nations Legislative Series compiling the practice of States and international organizations in the provisional application of treaties, as furnished by the latter over the years, together with other materials relevant to the topic.”

The below delineates the scope of Canada’s evolving practice on the provisional application of treaties.

2. Provisional application and Canada’s treaty adoption process

Canada most recently put forward its position on the role of provisional application in its treaty adoption process at the General Assembly debate on the 2021 Report of the International Law Commission (ILC):

Provisional application is an integral part of Canada’s treaty adoption process, though we generally prefer to rely on entry-into-force provisions as a straightforward mechanism. Canada’s current practice is that provisional application may only take effect following the signing of a treaty, and if no domestic implementing legislation is required. If implementing legislation is required, provisional application is delayed until the required legislation enters into force [emphasis added].Footnote 1

A similar position was articulated by Canada in a study published in 2001 by the Council of Europe (CoE) and the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL):

Provisional application is possible, for example, when such a provision is included in the legislation (e.g. the Department of Transport Act). If, however, changes in Canadian laws or regulations are necessary in order to enable the government of Canada to commit itself to provisional application of a treaty, appropriate legislative or regulatory action must be taken.Footnote 2

The approach taken in relation to the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) illustrates this practice. Article 30.7.3 of CETA allows Canada or the European Union (EU) to provisionally apply the treaty granted “that their respective internal requirements and procedures necessary for the provisional application of this Agreement have been completed.”Footnote 3 Canada therefore enacted the Canada–European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement Implementation Act and completed other necessary procedures to domestically implement CETA (e.g., administrative and regulatory changes) prior to the initiation of CETA’s provisional application pursuant to Article 30.7.3.Footnote 4

In addition to enacting any necessary legislative, regulatory or other changes, Canada also typically provides confirmation to the other State of the completion of Canada’s relevant domestic procedures to provisionally apply a given treaty and, if applicable, identifies the relevant provisions subject to provisional application (if the intent is to limit provisional application to certain provisions of the treaty).Footnote 5

Canada maintains that the ultimate objective is for States to take the necessary domestic steps to ensure that a treaty formally enters into force. Thus, provisional application should be seen as a “transitional stage” or measure that can facilitate the coming into force of a treaty.Footnote 6

3. Canada’s practice regarding the forms for prescribing or exercising provisional application

Article 25 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) specifies that provisional application may result from the provisions of the treaty in question (Article 25(a)). Provisional application may also occur “in some other manner” (Article 25(b)) as agreed by the negotiating States, including in the form of a separate treaty or, exceptionally, a decision or resolution adopted at an international organization or conference, or by a declaration of a State accepted by another State or international organization.Footnote 7

Canada’s practice is generally to prescribe provisional application in the treaty in question or alternatively as a separate treaty (typically through an exchange of notes or a protocol).

In the treaty in question (examples)

A series of bilateral treaties between Canada and Latin American States concluded between the mid-1940s and the mid-1950s include express provisions on their provisional application in the final clauses. These provisions stipulate that the treaty in question would apply provisionally upon signature or on a certain date, pending the treaty’s definitive entry into force.Footnote 8

The plurilateral Free Trade Agreement between Canada and the States of the European Free Trade Association (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) allows for the provisional application of the treaty and associated bilateral agreements, on condition that the domestic requirements of each State permit this provisional application.Footnote 9

In some other manner (examples)

An exchange of notes has been used to prescribe provisional applicationFootnote 10 or to extend provisional application that was prescribed by the initial treaty.Footnote 11 Canada has also prescribed provisional application in the form of a protocol with an international organization.Footnote 12

Canada has not prescribed or exercised provisional application through forms other than the treaty itself or by a separate agreement. Canada has expressed the need for greater clarity regarding the exercise of provisional application “in some other manner” as foreseen by Article 25(b) of the VCLT, particularly to clarify whether and, if so under what circumstances, consent for provisional application could be tacit or implied and produce legal effects.Footnote 13

4. Conclusion

Overall, provisional application is a voluntary and flexible mechanism that allows States to accommodate differences in their respective domestic treaty adoption requirements while not unduly delaying treaty implementation.Footnote 14 Canada’s views and practice on provisional application will continue to evolve based on our experience and that of other States.

2. Droit des traités

A. Application à titre provisoire des traités

L’application provisoire des traités est utilisée dans un nombre croissant de situations dans la pratique canadienne.

1. Introduction

L’application provisoire des traités est utilisée dans un nombre croissant de situations.

Au vu de cette tendance et de la pratique en évolution des États, le 9 décembre 2021, l’Assemblée générale a adopté la résolution 76/113, intitulée « Application à titre provisoire des traités », dans laquelle elle a prié « […] le Secrétaire général d’établir un volume de la Série législative des Nations Unies compilant la pratique des États et des organisations internationales en matière d’application à titre provisoire des traités, telle qu’elle s’est constituée au fil des ans, ainsi que d’autres documents relatifs au sujet ».

Ce qui suit esquisse la portée de la pratique en matière d’application à titre provisoire des traités telle qu’elle a évolué au Canada.

2. Application à titre provisoire et processus d’adoption des traités du Canada

Le Canada a récemment fait connaître sa position concernant le rôle de l’application à titre provisoire dans son processus d’adoption des traités dans le cadre du débat de l’Assemblée générale sur le Rapport de 2021 de la Commission du droit international (CDI):

L’application provisoire fait partie intégrante du processus d’adoption des traités au Canada, bien que nous préférions généralement nous appuyer sur des dispositions d’entrée en vigueur, puisqu’il s’agit d’un mécanisme plus simple. Au Canada, selon la pratique actuelle, l’application provisoire ne peut prendre effet qu’après la signature d’un traité, pour autant qu’aucune mesure législative de mise en œuvre nationale ne soit requise. Si une mesure législative de mise en œuvre est nécessaire, l’application provisoire est retardée jusqu’à l’entrée en vigueur de la mesure législativeFootnote 1 (italiques ajoutées).

Le Canada a exprimé une position semblable dans une étude publiée en 2001 par le Conseil de l’Europe (CE) et l’Institut britannique de droit international et de droit comparé (BIICL):

L’application à titre provisoire est par exemple possible lorsque cette disposition est prévue dans la législation (comme dans le cas de la loi relative au [ministère] des transports). Si, toutefois, il s’avère nécessaire de modifier des lois ou règlements pour permettre au Gouvernement canadien de s’engager à appliquer provisoirement un traité, des mesures législatives ou réglementaires ad hoc devront être prisesFootnote 2.

L’approche qui a été suivie à l’égard de l’Accord économique et commercial global entre le Canada et l’Union européenne (AECG) illustre cette pratique. L’article 30.7.3 de l’AECG permet au Canada ou à l’Union européenne (UE) d’appliquer à titre provisoire ce traité sous réserve de « l’accomplissement de leurs obligations et procédures internes respectives nécessaires à l’application provisoire du présent accordFootnote 3 ». Le Canada a donc promulgué la Loi de mise en œuvre de l’Accord économique et commercial global entre le Canada et l’Union européenne et accompli les autres procédures nécessaires à la mise en œuvre au niveau national de l’AECG (en procédant notamment à des modifications d’ordre administratif et réglementaire) avant d’amorcer l’application à titre provisoire de l’AECG conformément au paragraphe 30.7.3Footnote 4.

En plus de procéder aux modifications nécessaires de nature législative, réglementaire ou autre, le Canada fournit généralement à l’autre État une notification confirmant qu’il a accompli ses procédures internes requises pour l’application à titre provisoire du traité, en indiquant, le cas échéant, les dispositions visées par cette application (si les parties souhaitent limiter l’application à titre provisoire à certaines dispositions du traité)Footnote 5.

Le Canada est d’avis que l’objectif premier des États consiste à prendre les mesures nécessaires au plan interne pour que le traité puisse entrer officiellement en vigueur. Par conséquent, l’application à titre provisoire devrait être considérée comme une « étape transitoire » ou une mesure qui peut faciliter l’entrée en vigueur d’un traitéFootnote 6.

3. Pratique du Canada concernant les instruments pouvant être utilisés pour prévoir ou déclencher l’application à titre provisoire d’un traité

L’article 25 de la Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités (CVDT) énonce qu’un traité peut s’appliquer à titre provisoire si le traité lui-même en dispose ainsi (article 25 a)). Un traité peut également être appliqué provisoirement si les États ayant participé à la négociation en conviennent ainsi « d’une autre manière » (article 25 b)), y compris sous la forme d’un traité distinct ou, exceptionnellement, d’une décision ou d’une résolution adoptée par une organisation ou une conférence internationale, ou encore d’une déclaration d’un État acceptée par un autre État ou une organisation internationaleFootnote 7.

Dans la pratique, le Canada prévoit de façon générale qu’un traité fera l’objet de l’application à titre provisoire dans les dispositions du traité concerné, ou dans un traité distinct (prenant habituellement la forme d’un échange de notes ou d’un protocole).

Application à titre provisoire prévue dans les dispositions du traité concerné (exemples)

Plusieurs traités bilatéraux conclus entre le Canada et des États d’Amérique latine dans les années 1940-1950 comportent des dispositions expresses concernant leur application à titre provisoire dans les clauses finales. Ces dispositions prévoient que le traité s’appliquera provisoirement dès sa signature ou à partir d’une date particulière, en attendant son entrée en vigueur définitiveFootnote 8.

L’Accord de libre-échange entre le Canada et les États de l’Association européenne de libre‑échange (Islande, Liechtenstein, Norvège et Suisse) autorise l’application à titre provisoire de ce traité plurilatéral et des accords bilatéraux connexes à condition que les formalités internes de chaque État le permettentFootnote 9.

Application à titre provisoire dont les parties conviennent d’une autre manière (exemples)

Des échanges de notes ont été utilisés pour permettre l’application à titre provisoire d’un traitéFootnote 10 ou pour prolonger la période d’application à titre provisoire prévue par le traité initialFootnote 11. Le Canada a également conclu un protocole avec une organisation internationale à cette finFootnote 12.

Les seuls instruments que le Canada a utilisés jusque-là pour prévoir ou déclencher l’application à titre provisoire d’un traité sont le traité lui-même, ou un traité distinct. Le Canada a souligné la nécessité de clarifier les modalités de l’application à titre provisoire dans les cas où les États en conviennent ainsi « d’une autre manière », comme le prévoit l’article 25 b) de la CVDT, et en particulier de préciser si et, le cas échéant, dans quelles circonstances, un consentement à l’application à titre provisoire pourrait être tacite ou implicite et produire des effets juridiquesFootnote 13.

4. Conclusion

D’une manière générale, l’application à titre provisoire des traités est un mécanisme à caractère facultatif qui offre aux États la souplesse nécessaire pour s’adapter aux différences pouvant exister entre leurs exigences nationales respectives en matière d’adoption des traités, sans retarder indûment la mise en œuvre de ces derniersFootnote 14. Le point de vue et la pratique du Canada en matière d’application à titre provisoire continueront d’évoluer à la lumière de notre expérience et de celle d’autres États.

B. Subsequent agreements

Subsequent agreements under Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties — Canada’s treaty adoption process — Legal status and effect of Conference of the Parties (COP) decisions

Concerning a question on the legal status and effect of COP decisions under the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (Basel Convention), the Legal Affairs Bureau of Global Affairs Canada responded as follows:

A decision made by a Conference of Parties (COP) or other governing body of a convention is binding at international law if the underlying convention grants the governing body the authority to make such a decision binding on State Parties.Footnote 1 This is confirmed by Conclusion 11(2) of the ILC’s Draft conclusions on subsequent agreements and subsequent practice in relation to the interpretation of treaties (Draft Conclusions): “The legal effect of a decision adopted within the framework of a Conference of States Parties depends primarily on the treaty and any applicable rules of procedure.”Footnote 2

Article 15 of the Basel Convention, which establishes the COP and its mandate, grants it the power to adopt rules of procedures, rules governing the financial contributions of Parties under the Convention, and amendments to the Convention or its annexes as agreed by the Parties to the Convention. Article 15 appears to limit the COP’s mandate to such functions related to the effective administration of the treaty. It does not appear to grant the COP authority to issue a binding decision that would alter the obligations of the Parties to the Convention. Amendments to the Convention must be proposed by a Party to the Convention, adopted by consensus (ideally), and follow the formal treaty process.Footnote 3

However, a COP decision may advance a position on the interpretation of a Convention; for example, a COP decision may interpret or clarify a provision of the Convention in light of the particulars of a case at issue. Commentary on the above-referred Conclusion 11 of the Draft Conclusions clarifies that COP decisions may take the form of “subsequent agreements” or “understandings” under Article 31, paragraph 3(a) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), which “interpret the provisions of the Convention by defining, specifying or otherwise elaborating on the meaning and scope of the provisions, as well as through the adoption of guidelines on their implementation.”Footnote 4

It is crucial to distinguish the interpretative or clarificatory function of “subsequent agreements” under Article 31, paragraph 3 of the VCLT from subsequent amending agreements, which would engage the treaty amendment procedures under Articles 39-41 of the VCLT. From the domestic side, the amendment of a treaty would trigger Canada’s treaty adoption process. Indeed, Draft Conclusions 4 and 7 confirm that these “subsequent agreements” or “understandings” intend to build consensus around a particular interpretation of a treaty, not to amend the treaty.Footnote 5

Finally, despite the use of the word “agreement,” a “subsequent agreement” is not necessarily legally binding unless it takes the form of a treaty. Draft Conclusion 10(1) endorses this understanding: “An agreement under article 31, paragraph 3 (a) and (b) [of the VCLT], requires a common understanding regarding the interpretation of a treaty which the parties are aware of and accept. Such an agreement may, but need not, be legally binding for it to be taken into account” [emphasis added].

3. Immunities

A. Privileges and immunities of delegates attending the COP

The fifteenth Conference of the Parties (COP-15) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity took place in Montreal on 7–19 December 2022:

At the request of the United Nations and China, Canada agreed to host the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal from December 7 to 19, 2022. Canada succeeded in planning and delivering this conference, which welcomed over 12,000 delegates from all over the world.

A key element of hosting such a conference is to clearly define the responsibilities of all partners, including the host country and the United Nations or the multilateral organization partner. This is accomplished through the negotiation of an instrument between Canada and the relevant organization. In the case of COP15, Canada and the United Nations concluded a non-binding Memorandum of Understanding.

Hosting this type of international conference also involves a review of the rules on the privileges and immunities applicable to various delegates. The purpose of such privileges and immunities is not to benefit these individuals, but rather to ensure the efficient performance of their public functions while in Canada for the conference.

The Convention on Biological Diversity Secretariat is headquartered in Montreal. Canada had therefore already concluded a Host Country Agreement relating to the Secretariat and adopted the Privileges and Immunities of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Order under Canada’s Foreign Missions and International Organizations Act (FMIOA). These instruments provided the privileges and immunities necessary for various delegates participating in COP15.

Furthermore, representatives from United Nations Member States which are not party to the Convention on Biological Diversity were granted privileges and immunities during COP15 in accordance with the Privileges and Immunities Accession Order (United Nations), also adopted under the FMIOA.

To ensure Canada respected its obligations as the host of COP15, federal-provincial-municipal coordination was essential for awareness of the privileges and immunities afforded to certain delegates and the inviolability of the COP15 conference venue.

These contributions provided the “machinery” necessary for a positive outcome. COP15 saw the adoption of a historic deal to protect nature and biodiversity. Governments in attendance agreed to a set of international targets and goals for biodiversity called the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

4. Inter-state dispute settlement

A. International Court of Justice

Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine v Russian Federation) — Intervention — Joint Intervention of Canada and the Netherlands

On 7 December 2022, Canada and the Netherlands, relying on Article 63 of the Statute of the Court, filed in the Registry of the Court a joint declaration of intervention in the case concerning Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine v. Russian Federation). The full text of the declaration is available at <www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/182/182-20221207-WRI-02-00-EN.pdf>.

5. Cyberspace

A. Law applicable to cyberspace

Canada published a national statement on the application of international in cyberspace in April 2022.

Statement on the Application of International Law in Cyberspace

[French version follows the English one]

Abstract

Canada published a national statement on the application of international law in cyberspace in April 2022. This is part of our ongoing efforts, in particular through United Nations processes, to promote a free, open, stable and secure cyberspace. This statement sets out Canada’s current view on key aspects of international law applicable in cyberspace and explains how these apply. Canada’s views were consolidated through extensive interdepartmental consultations, in particular with the Department of National Defense, the Canadian Armed Forces and the Communications Security Establishment, and are well aligned with those of our closest allies and like-minded. Canada believes that the articulation of national positions on how international law applies to State action in cyberspace will increase international dialogue and the development of common understandings and consensus on lawful and acceptable State behaviour. These statements can help reduce the risk of misunderstandings and escalation between States arising from cyber activities. Recognizing the ongoing nature of technological change, Canada will continue to develop and publicise its views, including through dialogue with other States and stakeholders. This information is available in French and English at International Law applicable in cyberspace, <https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/peace_security-paix_securite/cyberspace_law-cyberespace_droit.aspx?lang=eng>.

***

Introduction

-

1. The recent rise in malicious online activities and rapid developments in cyber capabilities have led States to consider questions on how international law applies to State activity in cyberspace.

-

2. Canada supports the rules-based international order (RBIO), grounded in respect for international law. Canada considers that the RBIO extends to moderating State behaviour in cyberspace.Footnote 1 To this end, Canada has been active in multilateral efforts to create the framework for responsible State behaviour in cyberspace.Footnote 2

-

3. Canada is committed to reinforcing the application of international law in cyberspace and building on the international acquis on responsible State behaviour affirmed again last year by the United Nations (UN) Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) and Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG).Footnote 3 In plain terms, Canada believes that international law provides essential parameters for States’ behaviour in cyberspaceFootnote 4 and will continue to help ensure global stability and security.

-

4. Canada supports calls for States to develop and publish their national views on how international law applies in cyberspace. States have started stepping forward to issue statements on their national views. Canada is now in a position to do this ourselves. This follows several years of intensive consultations, reflection on the views of a range of States, and participation in formal and informal processes with States and other key stakeholders.Footnote 5

-

5. Canada believes that the articulation of national positions on how international law applies to State action in cyberspace will increase international dialogue and the development of common understandings and consensus on lawful and acceptable State behaviour. Footnote 6These statements can help reduce the risk of misunderstandings and escalation between States arising from cyber activities.

-

6. Canada continues to strongly advocate for capacity-building on the application of international law in cyberspace. We are committed to ensuring that the broadest possible group of States participates effectively in addressing these important questions, which increasingly affect all States.

-

7. This statement sets out Canada’s current view on key aspects of international law applicable in cyberspace and explains how these apply. Where possible we have included examples to better illustrate our position on a given aspect. Cyber-related challenges are magnified by rapid technological developments and the ever-increasing activities of malicious actors. Recognizing the ongoing nature of technological change, Canada will continue to develop and publicise its views, including through dialogue with other States and stakeholders.

General application of international law

-

8. Canada affirms that international law applies to the activities of every State in cyberspace. This includes the United Nations Charter (UN Charter) in its entirety and customary international law.Footnote 7 Canada recognizes the obligations of every State flowing from the principle of sovereignty to: refrain from the threat or use of force; settle disputes peacefully; and refrain from intervention in the internal affairs of other States. Canada further recognizes the obligations arising, in a non-exhaustive manner, from international human rights law (IHRL), international humanitarian law (IHL) and in relation to the law of State responsibility.

-

9. Canada supports agreed voluntary, non-binding norms for responsible State behaviour in cyberspace,Footnote 8 as a complement to international law, and continues to promote their implementation by all States.Footnote 9 Such voluntary norms do not replace or alter States’ binding obligations or rights under international law: they provide additional specific guidance on what constitutes responsible State behaviour.Footnote 10

Sovereignty

-

10. Sovereignty is a fundamental element of international law and international relations. It is axiomatic that the principle of sovereignty applies in cyberspace, just as it does elsewhere. It animates a number of obligations for all States.

-

11. In the relations between States, sovereignty signifies independence. It confers to each State the exclusive right to exercise the functions of a State within its territory.Footnote 11

-

12. This concept is also reflected in Canadian jurisprudence where Canada’s highest court found that “sovereignty” referred to “the various powers, rights and duties that accompany statehood under international law…”Footnote 12 and “…one of the organizing principles of the relationships between independent states”.Footnote 13

-

13. Territorial sovereignty is a rule under international law.Footnote 14 Every State must respect the territorial sovereignty of every other State. States enjoy sovereignty over their territory, including in particular infrastructure located within their territory and activities associated with that infrastructure. An infringement upon the affected State’s territorial integrity, or an interference with or usurpation of inherently governmental functions of the affected State, would be a violation of territorial sovereignty.Footnote 15

-

14. In assessing the possible infringement of a State’s territorial sovereignty, several key factors must be considered. The scope, scale, impact or severity of disruption caused, including the disruption of economic and societal activities, essential services, inherently governmental functions, public order or public safety must be assessed to determine whether a violation of the territorial sovereignty of the affected State has taken place.

-

15. In general, the impact or severity of cyber effects will be evaluated in the same manner and according to the same criteria as for physical activities. Cyber activities that rise above a level of negligible or de minimis effects, causing significant harmful effects within the territory of another State without that State’s consent, could amount to a violation of the rule of territorial sovereignty with respect to the affected State. It is also important to note that cyber activities with effects in another State do not constitute physical presence in the territory of that State. As such, territorial sovereignty is not violated by virtue merely of remote activities having been carried out on or through the cyber infrastructure located within the territory of another State. Furthermore, cyber activities carried out remotely from within Canada with negligible effects in a foreign State do not involve an extraterritorial exercise of enforcement jurisdiction by Canada.

-

16. Cyber activities that cause a loss of functionality with respect to cyber infrastructure located within the territory of the affected State may also constitute a violation of territorial sovereignty if the resulting loss of functionality causes significant harmful effects similar to those caused by physical damage to persons or property. For example, a violation of the territorial sovereignty will occur when the cyber activity creates a significant harmful effect that necessitates the repair or replacement of physical components of cyber infrastructure in the affected State. The loss of functionality of physical equipment that relies on the affected infrastructure in order to operate could also form part of the violation. The assessment of the effects includes both intended and unintended consequences that reach the threshold required to trigger a violation.

-

17. The rule of territorial sovereignty does not require consent for every cyber activity that has effects, including some loss of functionality, in another State. Activities causing negligible or de minimis effects would not constitute a violation of territorial sovereignty regardless of whether they are conducted in the cyber or non-cyber context. Nor are States precluded by the rule of territorial sovereignty from taking measures that have negligible or de minimis effects to defend against the harmful activity of malicious cyber actors or to protect their national security interests. For example, Canada considers that a cyber activity that requires rebooting or the reinstallation of an operating system is likely not a violation of territorial sovereignty.

-

18. The other key basis for assessing a violation of territorial sovereignty is whether a cyber activity interferes with or usurps the inherently governmental functions of another State. Cyber activities that have significant harmful effects on the exercise of inherently governmental functions would constitute an internationally wrongful act. For Canada, this would include government activities in areas such as health care services, law enforcement, administration of elections, tax collection, national defence and the conduct of international relations, and the services on which these depend. There can be a violation of territorial sovereignty by way of effects on governmental functions regardless of whether there is physical damage, injury, or loss of functionality. An example would be a cyber activity that interrupts health care delivery by blocking access to patient health records or emergency room services, resulting in risk to the health or life of patients.

-

19. Importantly, some cyber activities, such as cyber espionage, do not amount to a breach of territorial sovereignty, and hence to a violation of international law.Footnote 16 They may however be prohibited under the national laws of a State.Footnote 17

-

20. It is possible that a series of cyber activities could lead to significant harmful effects that violate the rule of territorial sovereignty. This is the case even if the individual cyber activity on its own would not reach this threshold.

-

21. Canada will assess whether a violation of territorial sovereignty has occurred on a case-by-case basis. As noted below, Canada believes further State practice and opinio juris will help clarify the scope of customary law in this area over time. In any event, Canada considers that the existence of varied approaches to assessing the legality of cyber activities should not prevent States from agreeing that particular malicious cyber activities are internationally wrongful acts.

Non-Intervention

-

22. State cyber activities may breach the foundational international law prohibition of intervention in the internal or external affairs of another State. This would be the case where both of the following conditions are met:

-

• the activities aim to interfere with the internal or external affairs of the affected State involving its inherently sovereign functions, known as domaine réservé Footnote 18; and

-

• the activities would cause coercive effects that deprive, compel, or impose an outcome on the affected State on matters in which it has free choice.Footnote 19

-

-

23. In its most serious form, coercion may arise through the threat or use of force but could also arise where a cyber activity is designed to deprive the affected State of its freedom of choice. Coercion must be distinguished from other conduct such as public diplomacy, criticism, persuasion, and propaganda.

-

24. An example of a prohibited intervention would be a malicious cyber activity that hacks and disables a State’s election commission days before an election, preventing a significant number of citizens from voting, and ultimately influencing the election outcome. Another example would be a malicious cyber activity that disrupts the functioning of a major gas pipeline, compelling the affected State to change its position in bilateral negotiations surrounding an international energy accord.

-

25. Whether or not a cyber activity meets the threshold for a violation of the rule on territorial sovereignty or rises to the level of a violation of the rule against intervention will be determined on a case-by-case basis. As with the thresholds for violations of territorial sovereignty, Canada believes that further State practice and opinio juris will help clarify the thresholds for the rule of non-intervention, and the scope of customary law in this area over time.

Due Diligence

-

26. No State should knowingly allow its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States.Footnote 20 This also applies in cyberspace. A State that has knowledge of a malicious cyber activity is expected to take all appropriate and reasonably available and feasible steps to stop ongoing or temporally imminent cyber activities that result or would result in significant harmful effects that impact the legal rights of another State.

-

27. The precise threshold that triggers this expectation will depend on the totality of the circumstances in that situation. This would include whether the State has knowledge of the wrongful acts, its technical and other capacities to detect and stop these acts, and what is reasonable in that case. For example, a State with limited technical capabilities would not likely be expected to respond if it failed to detect a malicious cyber activity emanating from or through cyber infrastructure on its territory. However, once aware, the State would be expected to respond.

State Responsibility

-

28. The international law of State responsibility applies across the whole spectrum of substantive areas of international law, including in cyberspace. It governs such issues as the attribution of internationally wrongful acts to States. It also addresses circumstances precluding wrongfulness, including countermeasures, and possible remedies. The law of State responsibility is not concerned with the legality of the use of force, including in self-defence, which is a separate area of international law.

-

29. In Canada’s view, this well-established body of international law is not only applicable, but highly relevant in relation to contemporary cyber activities. To date, all publicly known malicious cyber activities have been widely interpreted by States as falling below the threshold (or thresholds) of the threat or use of force or armed attacks.

Internationally Wrongful Acts

-

30. An internationally wrongful act in the cyber context is a cyber-related action or omission that:

-

• constitutes a breach of an international legal obligation, whether to another State or the entire international community; and

-

• is attributable to a State under international law.

-

-

31. International law recognises exceptions to what would otherwise be internationally wrongful acts. Examples include cases of self-defence and countermeasures.

Attribution

-

32. Canada applies the customary international law on State responsibility to attribute wrongful conduct in cyberspace. Under the law of State responsibility, an important element is that of attribution, which involves the identification of a State as legally responsible for an internationally wrongful act. A State can be responsible directly, or indirectly where a non-State actor has acted on the instructions of, or under the direction or control of, that State.Footnote 21 In this respect, States cannot escape legal responsibility for internationally wrongful cyber acts by perpetrating them through non-state actors who act on a State’s instruction or under its direction or control.Footnote 22

-

33. Attribution in its legal sense is of course distinct from the technical identification (or technical attribution) of the actor responsible for malicious cyber activity, whether State or non-State, as well as from the public denunciation of the responsible actor (political attribution). Further, Canada believes that the public attribution of internationally wrongful acts engages various political considerations beyond technical and legal attribution. To this end, States bear no obligation to publicly provide the basis upon which an attribution is made.

Countermeasures

-

34. Canada considers that States are entitled to use countermeasures in response to internationally wrongful acts including in cyberspace. The customary international law of State responsibility defines limits in the exercise of the right to take countermeasures, being actions that would otherwise be unlawful.Footnote 23 Countermeasures may not be taken in retaliation, but only to induce compliance, and directed at the State responsible for the internationally wrongful act. They may not constitute the threat or use of force, must be consistent with other peremptory norms of international law, and they must be proportional.

-

35. Lawful countermeasures in response to internationally wrongful cyber acts can be non-cyber in nature, and can include cyber operations in response to non-cyber internationally wrongful acts.

-

36. A State taking countermeasures is not obliged to provide detailed information equivalent to the level of evidence required in a judicial process to justify its cyber countermeasures; however, the State should have reasonable grounds to believe that the State that is alleged to have committed the internationally wrongful act was responsible for it. The precise scope of certain procedural aspects of countermeasures, such as notification, needs to be further defined through State practice given the unique nature of cyberspace.Footnote 24

-

37. Assistance can be provided on request of an injured State, for example where the injured State does not possess all the technical or legal expertise to respond to internationally wrongful cyber acts. However, decisions as to possible responses remain solely with the injured State. Canada has considered the concept of “collective cyber countermeasures” but does not, to date, see sufficient State practice or opinio juris to conclude that these are permitted under international law. Canada distinguishes “collective cyber countermeasures” from actions taken in “collective self-defence” including measures taken in cyberspace.

International human rights law (IHRL)

-

38. It is beyond dispute that international human rights law applies to activities in cyberspace. For many years, Canada has consistently advanced that all individuals enjoy the same human rights, and States are bound by the same human rights obligations, online just as offline.Footnote 25 States’ activities in cyberspace must be in accordance with their international human rights obligations as expressed in the international human rights treaties to which they are a party, and in customary international law.

-

39. Canada notes that according to Article 2(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, each State Party is required to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in that instrument, without distinction.Footnote 26

-

40. The internationally recognized human rights that are of particular concern in relation to cyberspace include the right to freedom of expression and to hold opinions without unlawful interference, freedom of association and of peaceful assembly, freedom from discrimination, and the right not to be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with one’s privacy or correspondence.

Peaceful Settlement of disputes

-

41. A central, and at times overlooked, rule of international law is the obligation of every State, under the UN Charter, to seek the settlement of disputes by peaceful means.Footnote 27 This is closely related to the prohibition of the threat or use of force.Footnote 28 Like that prohibition, it applies in cyberspace just as it does elsewhere. Thus, Canada considers that in line with the UN Charter, in case of disputes States may seek solutions through negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, and resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

-

42. The obligation to seek the settlement of disputes by peaceful means is not unlimited, nor does it diminish other international legal obligations or rights, such as the inherent right of self-defence.

-

43. Canada considers that a State may always respond to an unfriendly act or an internationally wrongful act with unfriendly acts provided they are not contrary to international law.

Threat or use of Force

-

44. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter requires that States refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the UN. This also applies in cyberspace. In general, cyber activities that amount to such a threat or use of force are unlawful, with recognised exceptions under international law.

-

45. In Canada’s view, cyber activities may amount to such a threat or use of force where the scale and effects are comparable to those from other operations that constitute the use of force at international law. Canada will assess cyber activities that may amount to a threat or use of force on a case-by-case basis.

Self-Defence against Armed Attack

-

46. Canada considers that the inherent right of self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a State also applies in cyberspace.Footnote 29

-

47. Canada will respond to cyber activities that amount to an armed attack in a manner that is consistent with international law. Canada’s response may include cyber operations. The right to self-defence is both an individual and collective right of States.

International Humanitarian Law (IHL)

-

48. IHL applies to cyber activities conducted in the context of both international and non-international armed conflict and regulates the conduct of hostilities and protects the victims of armed conflict.Footnote 30 In any armed conflict, the right of parties to choose means and methods of warfare is not unlimited.

-

49. Cyber activities are an attack under IHL, whether in offence or defence, where their effects are reasonably expected to cause injury or death to persons or damage or destruction to objects.Footnote 31This could include harmful effects above a de minimis threshold on cyber infrastructure, or the systems that rely on it. Such cyber activities must respect relevant treaty and customary IHL rules applicable to attacks including those relating to distinction, proportionality, and the requirement to take precautions in attack.

-

50. States that are Parties to Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions are required to review new weapons, means or methods of warfare to ensure compliance with IHL.Footnote 32 This obligation applies in the context of cyber capabilities and activities, although not all cyber capabilities and activities will constitute a weapon or means or method of warfare.

-

51. Canada emphasises that acknowledging the application of IHL to cyber activities in armed conflict neither contributes to militarising cyberspace nor legitimises cyber activities that are unlawful.Footnote 33

Conclusion

-

52. With this statement, Canada joins the many other States which have publicised their views on how international law applies in cyberspace. We hope that States which have not yet done so will consider publishing their own statements as well and thus contribute to the emergence of common understandings.

-

53. To that end, Canada will continue to actively support capacity building on international law and cyberspace. Canada has found the process of consultations that led to this statement to be very beneficial in developing a deeper understanding of how international law applies to cyberspace.

-

54. Canada believes it is crucial for all States to move beyond discussions of general concepts and build common understandings of what constitutes unlawful conduct in cyberspace. Canada will continue to develop and publicise its positions, including through dialogue with other States and stakeholders, in its ongoing efforts to contribute to security and stability in cyberspace.

***

Déclaration canadienne sur le droit international applicable dans le cyberespace

Résumé

Dans le cadre de nos efforts continues pour promouvoir un cyberespace ouvert, libre et sûr, notamment à travers les processus des Nations Unies, le Canada a publié une déclaration sur l’application du droit international dans le cyberespace, en avril 2022. Cette déclaration donne le point de vue actuel du Canada sur les aspects clés du droit international qui s’appliquent dans le cyberespace et explique comment ils s’appliquent. Les opinions du Canada ont été soutenus par de nombreuses consultations interdépartementales, notamment avec les Forces armées canadiennes, le ministère de la Défense et le Centre de la sécurité des télécommunications et sont en alignement à celles de nos alliés les plus proches et celles des autres pays aux points de vues similaires. Le Canada croit qu’exprimer publiquement le positionnement national sur la question de savoir comment le droit international s’applique aux actions que les états portent en cyberespace, va permettre à ce que le dialogue sur le plan international ait lieu et qu’il y ait un développement de la compréhension commune sur la conduite acceptable et légale d’un état. Ces déclarations pourraient aussi aider à réduire les risques d’incompréhensions et des escalades vers un conflit entre États suite à des cyberactivités. Le Canada reconnaît que la technologie est de nature à évoluer rapidement et constamment. Ainsi, le Canada continue à développer et publier ses opinions, entre autres en échangeant avec d’autres États et les autres parties prenantes. Cette information est disponible en français et en anglais: Droit international applicable dans le cyberespace <https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/peace_security-paix_securite/cyberspace_law-cyberespace_droit.aspx?lang=fra>.

Introduction

-

1. L’augmentation récente des activités malveillantes en ligne et l’évolution rapide des capacités cybernétiques ont conduit les États à s’interroger sur la manière dont le droit international s’applique aux activités des États dans le cyberespace.

-

2. Le Canada appuie l’ordre international fondé sur des règles (OIFR), ancré dans le respect du droit international. Le Canada considère que l’OIFR devrait encadrer le comportement des États dans le cyberespaceFootnote 1. C’est pourquoi le Canada a participé activement aux efforts multilatéraux visant à créer un cadre destiné à guider le comportement responsable des États dans le cyberespaceFootnote 2.

-

3. Le Canada est déterminé à renforcer l’application du droit international dans le cyberespace et à s’appuyer sur l’acquis international en matière de comportement responsable des États réitéré l’année passée par le Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux (GEG) et le Groupe de travail à composition non limitée (GTCNL) des Nations UniesFootnote 3. Le Canada estime que le droit international établit les paramètres essentiels du comportement des États dans le cyberespaceFootnote 4et qu’il continuera de contribuer à assurer la stabilité et la sécurité dans le monde.

-

4. Le Canada appuie les appels lancés aux États pour qu’ils élaborent et publient leurs points de vue nationaux sur la manière dont le droit international s’applique dans le cyberespace. Les États ont commencé à répondre à ces appels et à formuler des déclarations sur leurs points de vue nationaux. Le Canada est maintenant en mesure de le faire lui-même, et ce, à l’issue de plusieurs années de consultations intensives, de réflexion sur les points de vue exprimés par divers États, et de participation à des processus officiels et informels avec d’autres États et interlocuteurs clésFootnote 5.

-

5. Le Canada estime que la formulation de positions nationales sur la manière dont le droit international s’applique à l’activité de l’État dans le cyberespace permettra d’intensifier le dialogue international et de développer une compréhension commune et un consensus sur ce qui constitue un comportement acceptable et licite de l’ÉtatFootnote 6. Des déclarations de cette nature peuvent contribuer à réduire les risques de malentendus et d’escalade entre les États occasionnés par les cyberactivités.

-

6. Le Canada continue de préconiser avec force le renforcement des capacités en matière d’application du droit international dans le cyberespace. Nous sommes résolus à faire en sorte que le plus grand nombre possible d’États participent effectivement à l’examen de ces importantes questions, qui touchent de plus en plus l’ensemble des États.

-

7. La présente déclaration présente le point de vue actuel du Canada concernant les principaux aspects du droit international applicables dans le cyberespace, et explique la manière dont ils s’appliquent. Dans la mesure du possible, nous avons inclus des exemples pour mieux illustrer notre position sur les aspects abordés. Les défis liés au cyberespace sont accentués par les avancées technologiques rapides et la multiplication incessante des activités d’acteurs malveillants. Conscient de l’évolution constante des technologies, le Canada continuera de préciser et de communiquer ses points de vue, y compris dans le cadre de dialogues avec d’autres États et interlocuteurs.

Application générale du droit international

-

8. Le Canada affirme que le droit international s’applique aux activités de chaque État dans le cyberespace. Cela comprend la Charte des Nations Unies Footnote 7 dans son intégralité et le droit international coutumier Le Canada reconnaît les obligations qui incombent à chacun des États du fait du principe de souveraineté, à savoir : s’abstenir de recourir à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force ; régler les différends par des moyens pacifiques; et s’abstenir de toute intervention dans les affaires intérieures d’un autre État. Le Canada reconnaît en outre les obligations découlant, entre autres, du droit international en matière de droits de la personne (DIDP), du droit international humanitaire (DIH) et du droit de la responsabilité des États.

-

9. Le Canada soutient des normes non contraignantes convenues sur une base facultative en matière de comportement responsable des États dans le cyberespaceFootnote 8, en complément du droit international, et continue d’en promouvoir la mise en œuvre par tous les ÉtatsFootnote 9. Ces normes facultatives ne viennent ni remplacer ni modifier les obligations contraignantes ou les droits des États au titre du droit international : elles apportent des orientations plus précises sur ce qui constitue un comportement responsable des ÉtatsFootnote 10.

Souveraineté

-

10. La souveraineté est un élément fondamental du droit international et des relations internationales. Il va de soi que le principe de souveraineté s’applique dans le cyberespace, au même titre qu’ailleurs. Ce principe sous-tend plusieurs obligations qui incombent à tous les États.

-

11. Dans les relations entre États, la souveraineté signifie l’indépendance. Elle confère à chaque État le droit exclusif d’exercer les fonctions de l’État sur son territoireFootnote 11.

-

12. Ce concept trouve aussi son expression dans la jurisprudence canadienne, le plus haut tribunal du Canada ayant conclu que la « souveraineté » s’entend des « différents pouvoirs, droits et obligations que confère la qualité d’État en droit internationalFootnote 12» et qu’elle est « l’un des principes fondateurs des relations entre les États indépendantsFootnote 13 ».

-

13. La souveraineté territoriale est une règle du droit internationalFootnote 14. Chaque État doit respecter la souveraineté territoriale de chacun des autres États. Les États jouissent d’une souveraineté sur leur territoire, y compris sur les infrastructures qui s’y trouvent et les activités connexes. Une atteinte à l’intégrité territoriale de l’État touché, une ingérence dans les fonctions intrinsèquement gouvernementales de l’État touché, ou encore une usurpation de ces fonctions, constituerait une violation de la souveraineté territorialeFootnote 15.

-

14. Pour évaluer une éventuelle atteinte à la souveraineté territoriale d’un État, plusieurs facteurs clés doivent être pris en compte. La portée, l’ampleur, les répercussions ou la gravité de la perturbation causée, y compris la perturbation des activités économiques et sociétales, des services essentiels, des fonctions intrinsèquement gouvernementales, de l’ordre public ou de la sécurité publique, doivent être évaluées pour déterminer si une violation de la souveraineté territoriale de l’État touché a eu lieu.

-

15. En général, les répercussions ou la gravité des cybereffets seront évaluées de la même façon et selon les mêmes critères que pour les activités tangibles. Les cyberactivités dont les effets dépassent le seuil du négligeable ou de minimis, qui entraînent des effets dommageables importants sur le territoire d’un autre État sans le consentement de ce dernier, pourraient constituer une violation de la règle de souveraineté territoriale à l’égard de l’État touché. Il importe également de noter que les cyberactivités ayant des effets dans un autre État ne constituent pas une présence physique sur le territoire de cet État. Par conséquent, la souveraineté territoriale n’est pas violée du seul fait que des activités à distance ont été menées à partir de ou via la cyberinfrastructure située sur le territoire d’un autre État. De plus, les cyberactivités menées à distance à partir du Canada qui ont des effets négligeables dans un État étranger ne donnent pas lieu à un exercice extraterritorial de la compétence d’exécution par le Canada.

-

16. Les cyberactivités qui entraînent une perte de fonctionnalité en lien avec une cyberinfrastructure située sur le territoire de l’État touché peuvent également constituer une violation de la souveraineté territoriale si la perte de fonctionnalité qui en résulte entraîne des effets dommageables importants similaires à ceux causés par des dommages physiques à des personnes ou à des biens. À titre d’exemple, il y aura violation de la souveraineté territoriale lorsque la cyberactivité crée un effet dommageable important qui nécessite la réparation ou le remplacement de composantes physiques de la cyberinfrastructure dans l’État touché. La perte de fonctionnalité des équipements physiques qui dépendent de l’infrastructure touchée pour fonctionner pourrait également faire partie de la violation. L’évaluation des effets porte à la fois sur les conséquences intentionnelles et les conséquences non intentionnelles qui atteignent le seuil requis pour constituer une violation.

-

17. La règle de souveraineté territoriale n’exige pas le consentement pour chaque cyberactivité qui entraîne des effets, y compris une certaine perte de fonctionnalité, dans un autre État. Les activités ayant des effets négligeables/de minimis ne constitueraient pas une violation de la souveraineté territoriale, qu’elles soient menées dans un contexte cybernétique ou non. La règle de souveraineté territoriale n’empêche pas non plus les États de prendre des mesures ayant des effets négligeables/de minimis pour se défendre contre l’activité nuisible de cyberacteurs malveillants ou pour protéger leurs intérêts en matière de sécurité nationale. À titre d’exemple, le Canada considère qu’une cyberactivité qui nécessite le redémarrage ou la réinstallation d’un système d’exploitation ne constitue probablement pas une violation de la souveraineté territoriale.

-

18. L’autre critère essentiel pour évaluer une violation de la souveraineté territoriale est de savoir si une cyberactivité constitue une ingérence dans les fonctions intrinsèquement gouvernementales d’un autre État ou une usurpation de ces dernières. Les cyberactivités qui ont des effets dommageables importants sur l’exercice de fonctions intrinsèquement gouvernementales constitueraient un fait internationalement illicite. Pour le Canada, cela comprendrait les activités gouvernementales dans des domaines tels que les services de santé, l’application de la loi, l’administration des élections, la perception des impôts, la défense nationale et la conduite des relations internationales, ainsi que les services dont ces activités dépendent. Il peut y avoir une violation de la souveraineté territoriale en raison des effets produits sur les fonctions gouvernementales, qu’il y ait ou non des dommages physiques, un préjudice ou une dégradation fonctionnelle. Il pourrait s’agir, par exemple, d’une cyberactivité qui interrompt la prestation de soins de santé en bloquant l’accès aux dossiers médicaux des patients ou aux services d’urgence, entraînant ainsi un risque pour la santé ou la vie des patients.

-

19. Il importe de souligner que certaines cyberactivités, comme le cyberespionnage, ne constituent pas une atteinte à la souveraineté territoriale, et ne donnent donc pas lieu à une violation du droit internationalFootnote 16. Elles peuvent toutefois être interdites par la législation nationale d’un ÉtatFootnote 17.

-

20. Il est possible qu’une série de cyberactivités entraîne des effets dommageables importants qui constituent une violation de la règle de souveraineté territoriale, et ce, même si la cyberactivité prise isolément n’atteint pas ce seuil.

-

21. Le Canada évaluera au cas par cas si une violation de la souveraineté territoriale s’est produite. Comme il est indiqué ci-après, le Canada estime que la portée du droit coutumier dans ce domaine sera précisée au fil du temps tant par la pratique des États que par l’opinio juris. En tout état de cause, le Canada considère que les différentes approches en voie d’élaboration ne devraient pas empêcher les États de convenir que certaines cyberactivités malveillantes constituent des faits internationalement illicites.

Non-intervention

-

22. Les cyberactivités menées par un État peuvent enfreindre le principe fondamental du droit international interdisant toute intervention dans les affaires intérieures ou extérieures d’un autre État. Cela se produit lorsque les deux conditions suivantes sont réunies:

-

• les activités sont menées dans le but de s’ingérer dans les affaires intérieures ou extérieures de l’État touché relevant de ses fonctions intrinsèquement souveraines, c.-à-d. de son domaine réservéFootnote 18;

-

• les activités ont des effets coercitifs qui privent l’État touché d’un résultat ou visent à obtenir ou à imposer un résultat à l’État touché sur des questions dont il devrait pouvoir décider librementFootnote 19.

-

-

23. Dans sa forme la plus grave, la contrainte peut se traduire par un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force, mais il peut aussi s’agir d’une cyberactivité qui vise à priver l’État touché de sa liberté de choix. La contrainte ne doit pas être confondue avec d’autres pratiques telles que la diplomatie publique, la critique, la persuasion et la propagande.

-

24. À titre d’exemple, une intervention interdite pourrait prendre la forme d’une cyberactivité malveillante de piratage qui paralyse les systèmes de la commission électorale d’un État quelques jours avant un scrutin, empêchant un grand nombre de citoyens d’aller voter, et influençant ainsi le résultat des élections. Un autre exemple serait celui d’une cyberactivité malveillante qui perturberait le fonctionnement d’un important gazoduc, obligeant ainsi l’État touché à modifier sa position dans des négociations bilatérales sur un accord énergétique international.

-

25. La question de savoir si une cyberactivité donnée répond aux critères requis pour constituer une violation de la règle relative à la souveraineté territoriale, ou si elle donne plutôt lieu à une violation de la règle de non‑intervention, sera examinée au cas par cas. Le Canada estime que, tout comme les critères applicables aux violations de la souveraineté territoriale, les critères relatifs à la règle de non‑intervention et la portée du droit coutumier dans ce domaine seront précisés au fil du temps par la pratique des États et par l’opinio juris.

Diligence raisonnable

-

26. Aucun État ne devrait permettre sciemment que son territoire soit utilisé aux fins d’actes contraires aux droits d’autres ÉtatsFootnote 20. Cette obligation s’applique aussi dans le cyberespace. On s’attend à ce qu’un État qui a connaissance d’une cyberactivité malveillante prenne toutes les mesures adéquates, possibles et raisonnables dans une situation donnée pour arrêter des cyberactivités en cours ou imminentes qui entraînent ou entraîneraient des effets dommageables importants ayant une incidence sur les droits d’un autre État.

-

27. Le seuil précis déclenchant cette attente dépendra de l’ensemble des circonstances dans une situation donnée. Il s’agira notamment de savoir si l’État a connaissance des faits illicites, de quelles capacités techniques et autres il dispose pour détecter ces faits et les arrêter, et de ce qui est raisonnable dans ce cas. Par exemple, on ne s’attendrait vraisemblablement pas à ce qu’un État disposant de capacités techniques limitées réagisse s’il n’a pas détecté une cyberactivité malveillante menée à partir d’une infrastructure informatique située sur son territoire ou via celle-ci. Toutefois, dès que l’État en aura connaissance, il devra agir.

Responsabilité de l’État

-

28. Le droit international de la responsabilité des États s’applique à l’ensemble des domaines de fond du droit international, y compris au cyberespace. Il régit des questions telles que l’attribution de faits internationalement illicites à des États. Il traite également des circonstances excluant l’illicéité, y compris les contre-mesures, et des recours possibles. Le droit de la responsabilité des États n’aborde pas la question de la légalité de l’emploi de la force, y compris en cas de légitime défense, qui est un domaine distinct du droit international.

-

29. Le Canada est d’avis que cet ensemble de règles bien établies en droit international est non seulement applicable, mais aussi très pertinent au regard des cyberactivités contemporaines. Jusqu’à maintenant, les États ont largement considéré qu’aucune des cyberactivités malveillantes connues publiquement n’a atteint le seuil (ou les seuils) requis pour constituer un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force, ou une attaque armée.

Faits internationalement illicites

-

30. Dans le contexte du cyberespace, un fait internationalement illicite désigne une action ou une omission liées à une activité de nature cybernétique qui:

-

• d’une part, enfreint une obligation juridique internationale, que ce soit envers un autre État ou la communauté internationale dans son ensemble;

-

• d’autre part, est attribuable à un État en vertu du droit international.

-

-

31. Le droit international reconnaît des exceptions à ce qui constituerait par ailleurs un fait internationalement illicite, par exemple les cas de légitime défense et la prise de contre-mesures.

Attribution

-

32. Le Canada applique le droit international coutumier sur la responsabilité des États pour attribuer des actes illicites commis dans le cyberespace. L’attribution, qui constitue un élément important du droit sur la responsabilité des États, implique la désignation de l’État légalement responsable d’un fait internationalement illicite. Un État peut être responsable directement ou indirectement lorsqu’un acteur non étatique a agi sur les instructions ou les directives ou sous le contrôle de cet ÉtatFootnote 21. Ainsi, un État ne peut échapper à sa responsabilité en droit à l’égard d’un fait internationalement illicite commis dans le cyberespace en le perpétrant par l’intermédiaire d’acteurs non étatiques agissant sur ses instructions ou ses directives ou sous son contrôleFootnote 22.

-

33. L’attribution au sens juridique est bien entendu distincte de l’identification technique (attribution technique) du responsable d’une activité malveillante dans le cyberespace, qu’il s’agisse d’un État ou d’un acteur non étatique, ainsi que de la dénonciation publique du responsable (attribution politique). De plus, le Canada est d’avis que l’attribution dans la sphère publique de faits internationalement illicites comporte d’autres considérations d’ordre politique allant au-delà de l’attribution technique. À cette fin, les États ne sont pas tenus de communiquer publiquement les éléments sur lesquels ils se fondent pour attribuer un acte donné.

Contre-mesures

-

34. Le Canada considère que les États ont le droit de recourir à des contre-mesures en réponse à des faits internationalement illicites, y compris dans le cyberespace. Le droit international coutumier sur la responsabilité des États fixe des limites à l’exercice du droit de prendre des contre-mesures, puisqu’il s’agit d’actions qui seraient par ailleurs illicitesFootnote 23 Les contre-mesures ne peuvent pas être prises à titre de représailles, mais seulement pour obtenir l’exécution des obligations, et elles doivent être dirigées contre l’État responsable du fait internationalement illicite. Les contre-mesures ne peuvent pas constituer un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force, et elles doivent être proportionnelles et conformes aux autres normes impératives du droit international.

-

35. Les contre-mesures licites prises en réponse à des faits internationalement illicites commis dans le cyberespace ne doivent pas nécessairement être de nature cybernétique, et peuvent comprendre des cyberopérations menées en réponse à des faits internationalement illicites qui n’ont pas été commis dans le cyberespace.

-

36. L’État qui impose des contre-mesures n’est pas tenu de fournir des renseignements détaillés répondant à des normes de preuve équivalentes à celles applicables à une procédure judiciaire pour justifier les contre-mesures qu’il prend dans le cyberespace ; toutefois, cet État devrait avoir des motifs raisonnables de croire que l’État auquel on reproche d’avoir commis le fait internationalement illicite est responsable de celui-ci. La portée précise de certains aspects procéduraux des contre-mesures, comme la notification, devra être définie de manière plus approfondie par la pratique des États, compte tenu de la nature unique du cyberespaceFootnote 24.

-

37. Une assistance peut être fournie à la demande d’un État lésé, par exemple lorsque ce dernier ne dispose pas de toute l’expertise technique ou juridique requise pour réagir à un fait internationalement illicite commis dans le cyberespace. Toutefois, les décisions concernant les réactions possibles relèvent exclusivement de l’État lésé. Le Canada s’est penché sur le concept de « contre-mesures collectives dans le cyberespace », mais estime que la pratique des États et l’opinio juris ne permettent pas, à l’heure actuelle, de conclure que de telles mesures sont permises en vertu du droit international. Le Canada établit une distinction entre les « contre-mesures collectives dans le cyberespace » et les mesures prises pour assurer la « légitime défense collective », y compris celles prises dans le cyberespace.

Droit international en matière de droits de la personne (DIDP)

-

38. Il est incontestable que le droit international en matière de droits de la personne s’applique aux activités dans le cyberespace. Depuis de nombreuses années, le Canada soutient invariablement le principe selon lequel tous les individus jouissent des mêmes droits de la personne, et les États sont liés par les mêmes obligations en matière de droits de la personne, et ce, en ligne et hors ligneFootnote 25. Les activités des États dans le cyberespace doivent être conformes à leurs obligations internationales en matière de droits de la personne, telles qu’elles sont exprimées dans les traités internationaux relatifs aux droits de la personne auxquels ils sont parties et dans le droit international coutumier.

-

39. Le Canada note que, en vertu de l’article 2(1) du Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques Footnote 26, chaque État partie est tenu de respecter et de garantir à tous les individus se trouvant sur son territoire et relevant de sa compétence les droits reconnus dans cet instrument, sans distinction aucune.

-

40. Les droits de la personne internationalement reconnus qui suscitent des préoccupations particulières en ce qui concerne le cyberespace comprennent le droit à la liberté d’expression sans crainte d’être inquiété pour ses opinions, la liberté d’association et de réunion pacifique, le droit d’être libre de discrimination et le droit de ne pas faire l’objet d’interférence arbitraire ou illégale dans sa vie privée ou sa correspondance.

Règlement pacifique des différends

-

41. L’obligation de chercher à régler les différends par des moyens pacifiques qui incombe à chacun des États en vertu de la Charte des Nations Unies constitue une règle centrale, et parfois oubliée, du droit internationalFootnote 27. Cette obligation est étroitement liée à l’interdiction de recourir à la menace ou à l’emploi de la forceFootnote 28. À l’instar de cette dernière, elle s’applique dans le cyberespace comme partout ailleurs. Ainsi, le Canada estime que, comme le prévoit la Charte des Nations Unies, les États peuvent rechercher la solution de leurs différends par voie de négociation, d’enquête, de médiation, de conciliation, d’arbitrage, de règlement judiciaire, de recours aux organismes ou accords régionaux, ou par d’autres moyens pacifiques de leur choix.

-

42. L’obligation de chercher à régler les différends par des moyens pacifiques n’est cependant pas illimitée, et elle ne restreint pas les autres droits ou obligations juridiques internationaux, comme le droit naturel de légitime défense.

-

43. Le Canada considère qu’un État peut toujours répondre à un acte inamical ou à un fait internationalement illicite par des actes inamicaux à condition que ceux-ci ne soient pas contraires au droit international.

Menace ou emploi de la force

-

44. L’article 2(4) de la Charte des Nations Unies requiert que les États s’abstiennent, dans leurs relations internationales, de recourir à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force, soit contre l’intégrité territoriale ou l’indépendance politique de tout État, soit de toute autre manière incompatible avec les buts des Nations Unies. Cette obligation s’applique aussi dans le cyberespace. En règle générale, une cyberactivité est illicite si elle constitue un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force.

-

45. Le Canada estime qu’une cyberactivité peut constituer un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force lorsque son ampleur et ses effets sont comparables à ceux d’autres opérations qui constituent un emploi de la force en droit international. Le Canada évaluera au cas par cas les cyberactivités qui pourraient constituer un recours à la menace ou à l’emploi de la force.

Légitime défense face à une agression armée

-

46. Le Canada considère que le droit naturel de légitime défense d’un État face à une agression armée s’applique également dans le cyberespaceFootnote 29.

-

47. Le Canada réagira aux cyberactivités qui constituent une agression armée d’une manière conforme au droit international, y compris en recourant à des cyberopérations s’il y a lieu. Le droit de légitime défense des États est à la fois individuel et collectif.

Droit international humanitaire (DIH)

-

48. Le DIH s’applique aux cyberactivités menées dans le contexte des conflits armés internationaux et des conflits armés non internationaux, il régit la conduite des hostilités, et protège les victimes des conflits armésFootnote 30. Dans un conflit armé, le droit des parties de choisir les moyens et méthodes de guerre n’est pas illimité.

-

49. Les cyberactivités constituent une attaque au sens du DIH, qu’elles soient menées à titre offensif ou défensif, lorsque leurs effets sont raisonnablement susceptibles de causer la mort ou des blessures à des personnes ou la dégradation ou la destruction d’objetsFootnote 31. Cela pourrait comprendre des effets nocifs dommageables supérieurs à un seuil de minimis lorsqu’il s’agit de la cyberinfrastructure ou des systèmes qui en dépendent. Les cyberactivités de ce type doivent respecter les règles du DIH conventionnel et coutumier applicables aux attaques, y compris celles relatives au principe de distinction, à la proportionnalité et à l’obligation de prendre des précautions lors d’une attaque.

-

50. Les États parties au Protocole additionnel I aux Conventions de Genève sont tenus d’examiner les nouvelles armes et les nouveaux moyens ou méthodes de guerre pour s’assurer de leur conformité au DIHFootnote 32. Cette obligation s’applique dans le contexte des capacités et activités cybernétiques, même si toutes les capacités et activités de ce type ne constituent pas une arme ou un moyen ou une méthode de guerre.

-

51. Le Canada tient à souligner que la reconnaissance du fait que le DIH s’applique aux cyberactivités lors des conflits armés ne contribue pas à la militarisation du cyberespace et ne vient pas légitimer les cyberactivités illicitesFootnote 33.

Conclusion

-

52. En publiant la présente déclaration, le Canada se joint aux nombreux États qui ont fait connaître publiquement leurs points de vue concernant la manière dont le droit international s’applique dans le cyberespace. Nous espérons que les États qui ne l’ont pas encore fait envisageront de publier eux aussi leurs propres déclarations et contribueront ainsi à l’émergence d’une compréhension commune.

-

53. À cette fin, le Canada continuera de soutenir activement le renforcement des capacités en matière de droit international et de cyberespace. Le processus de consultations qui a abouti à la présente déclaration nous a permis de beaucoup mieux comprendre la manière dont le droit international s’applique dans le cyberespace.

-

54. Le Canada estime qu’il est essentiel pour tous les États de dépasser les discussions sur les concepts généraux, et de développer une interprétation commune de vues sur ce qui constitue un comportement illicite dans le cyberespace. Le Canada continuera de développer et de communiquer ses positions, y compris au moyen d’un dialogue avec d’autres États et interlocuteurs, dans le cadre des efforts constants qu’il déploie pour contribuer à la sécurité et à la stabilité dans le cyberespace.

6. Law of the sea

A. Continental shelf

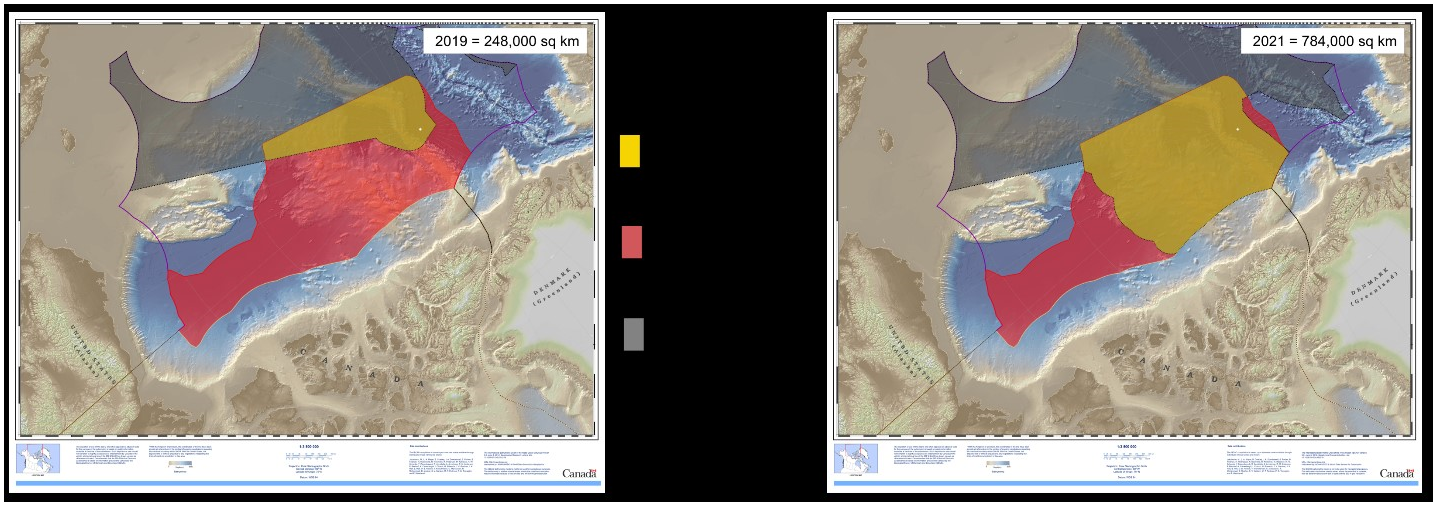

Canada made a revised submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) on 19 December 2021.

Canada’s Continental Shelf in the Arctic Ocean