This timely book is a fascinating exploration of the development of ‘Phoenician’ as an identifier for the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age inhabitants of coastal Levantine cities and their associated colonies in the Western Mediterranean, most famously Carthage. Its title is cleverly reminiscent of other archaeological works for a wider audience that present a quest-style narrative, a ‘bringing to light’ of an ancient people, a map leading to buried treasure. It is, however, made very clear from the outset that the titular ‘search’ for the Phoenicians is not going to provide the usual result.

Quinn’s central thesis is that there was no overarching ‘Phoenician’ identity that brought together the citizens of Tyre, Sidon, Byblos and other cities, and that their collective identification as ‘Phoenician’ is an entirely etic phenomenon. This treasure hunt is more complex than a straightforward review of the archaeological and textual evidence, or an update of Sabatino Moscati’s seminal The world of the Phoenicians (Reference Moscati1968). Instead, Quinn interrogates the notion of shared identity in the ancient past, the political manipulation of archaeology in recent history and the continued importance of these charged interpretations in the present day.

The book is arranged in three parts, forming a journey backwards in time and then forwards again. After a blazing Introduction drawing on the playwright Brian Friel’s explorations of colonisation, violence and belonging, the first part opens with a discussion of the role of perceived Phoenician heritage in the modern nation state of Lebanon. Quinn focuses on the exceptionalist rhetoric used to carve out Lebanese nationhood, into which both classical sources and archaeology were conscripted. She then moves to assess definitions of ethnicity and shared identity, before demonstrating that no communal self-designation exists beyond the level of the city in texts produced by individuals from the region. The argument then widens from these inhabitants of Carthage and kings of Sidon and Byblos, to the views of outsiders: Greek and Roman sources weighing in on Phoenicia and Phoenicians.

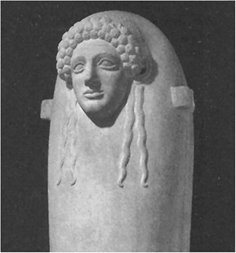

In the second part, Quinn focuses on material culture, initially using coins, carving styles and burial practices to illustrate her argument that “there is very little in their cultural artefacts or behaviour to suggest self-conscious community-building at the level of ‘Phoenician’” (p. 66) until the late fifth century BC, and then only in Carthage. Two chapters follow, exploring the role of religion in the construction of homeland and diasporic communities. The first is centred on Tophet sites—“open air enclosures containing the urn burials of cremated infants and animals” (p. 92); the second on the cult of Melqart, and his representation as and relationship with Herakles and other ‘Master of Animals’ deities. Quinn convincingly argues that while Tophet sites may be seen as a declaration of difference, worship of Melqart invoked wider connections and became an important political tool, superseding the more inward-looking Tophet cult.

The only slight criticism possible of this carefully orchestrated and meticulous volume is that there are occasional mismatches between the text and the audience it is aimed at in these middle chapters. The general reader, whether classicist or archaeologist, if not au fait with the evidence and arguments that Quinn references, may feel confused by the decision not to engage with these to a deeper degree. For example, in her discussion of the highly emotive practice of child sacrifice, Quinn judiciously decides to focus on the role of the cult in “the construction of colonial communities” (p. 92). Her argument is, however, based upon accepting that such sacrifices took place and were not invented as propaganda. More of the briefly referenced osteological evidence, “incompatible with normal patterns of infant mortality” (p. 93), would have greatly strengthened her position. It is entirely understandable that Quinn did not wish to either sensationalise or repeat arguments that are very familiar within Phoenician studies, but in a work for the non-specialist, this decision somewhat undermines the argument that follows. Similarly, the discussion and dismissal of ceramic evidence as too deeply enmeshed with cultural-historical interpretative models required more justification to the non-specialist, particularly in the light of developing archaeometric analyses.

In the third and final part of the book, Quinn begins to move forward in time once again, beginning with the third or fourth century AD and the context of the first self-declared Phoenician author. She explores “the increasing popularity of […] the idea of being Phoenician in the Hellenistic and Roman periods” (p. 136), tracing the invention of a shared Phoenician identity from the death of Alexander, before refocusing in a chapter on the Western Mediterranean. This incorporates a particularly strong discussion using bilingual inscriptions from Lepcis Magna to illustrate the city’s deliberate deployment of the Phoenician past to preserve, subtly, its own political autonomy under Rome. The final chapter explores the reception of and reaction to ideas of Phoenician identity in medieval, Early Modern and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain and Ireland, including a fascinating assessment of the highly politicised idea of Phoenician colonists in both Cornwall and Ireland. The powerful ending returns to the Irish context with which the book began: from a Brian Friel play to a piece by Frank McGuinness. Carthaginians and Baglady (Reference McGuinness1988) is set against the background of the Troubles, and Quinn closes her work with the emotive words of its character Dido, Queen of Derry, who declares that she is “Surviving. Carthage has not been destroyed” (p. 208).

As demonstrated in this excellent book, Phoenician identity has not only not been destroyed, but has thrived, taking on power and meaning time and again. This search for the Phoenicians finds more than buried treasure, seeking out both the bonds that built communities in the ancient world and the phantasms that were reinvented to shape nations and spur resistance in the modern one. It deserves a wide audience, and will challenge, intrigue and capture the attention of archaeologists, classicists and non-specialists alike.