A. Introduction

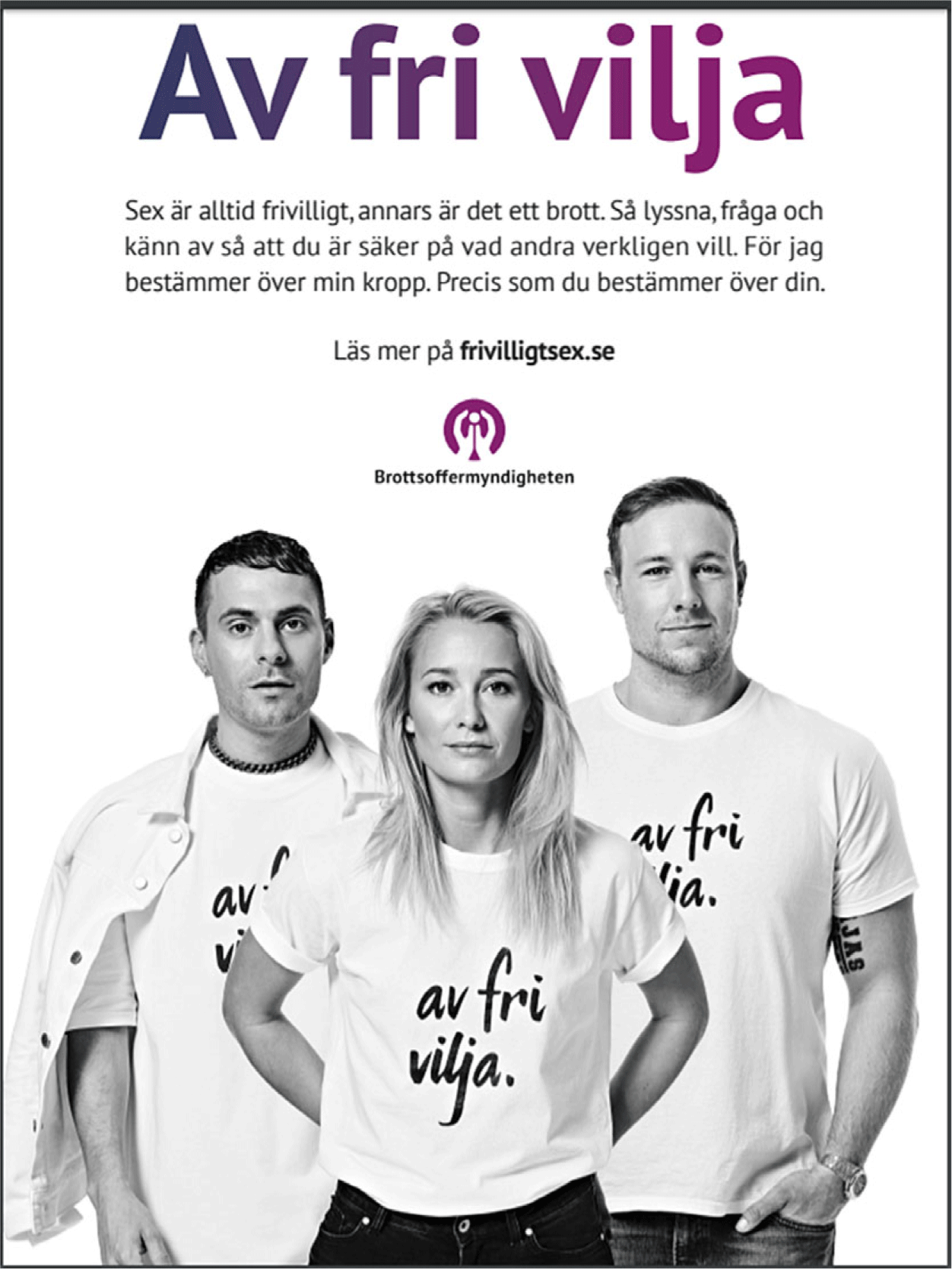

Figure 1 comes from a campaign initiated by the Swedish governmentFootnote 1 to provide information about a new rape law introduced in July 2018.Footnote 2 The image’s text reads: “Of [your own] free will. Sex is always voluntary; if it’s not, it’s a crime. So, listen, ask, and tune in so that you’re sure what others really want. Because I decide about my body. Just like you decide about yours.”Footnote 3

Figure 1. Campaign poster about the new rape law in Sweden. Credit: the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority/Eva Edsjö.

Figure 1 illustrates how the new crime of rape in Sweden—defined based on nonvoluntary participation—is framed as a matter of sex, choice, and communication. When the campaign states that “Sex is voluntary; if it’s not, it’s a crime,” sex and crime are juxtaposed. The statement involves a description of what sex is—something voluntary, mutual, and communicative. Rape is disrespecting another person’s choice: “I decide about my body” and “[y]ou decide about yours.” Rape is represented as a problem of communication: The campaign assumes that individuals can express their will and encourages them to “listen, ask, and tune in.” The campaign also provides advice and conveys the message that it is important for individuals to talk about sex—about what they want and feel.Footnote 4 The picture exemplifies the main theme of this article, namely, that the new rape law is coupled with an emerging problem within such disparate spheres as public health, social media campaigns, sexual education, and gender studies. I refer to it as the problem of sexual communication. In short, criminal law is woven into a sexual education imperative. To understand this new representation of rape, I suggest further exploration into the effects of framing sexual violence as a matter of individual choice, consent, and communication in late modernity and into the role of criminal law in the era of thin normativity. I also offer the more concrete suggestion that the application and interpretation of the new rape law should consider knowledge production within the discursive field of sexual communication.

A push to replace outdated sex offense regulations with laws that accurately correspond to late modern ideas about gender equality and sexual self-determination is taking place in many jurisdictions in Europe and North America, in addition to in international criminal law.Footnote 5 The move away from force and coercion towards consent has engendered various legislative models, such as “no means no” and “only yes means yes”—also known as affirmative consent—Footnote 6and proposals to reframe rape in terms of “coercive context,”Footnote 7 “consent-plus,”Footnote 8 and “freedom to negotiate.”Footnote 9 In the last few years, all of the Nordic countries have had vibrant discussions on rape law reform.Footnote 10 Iceland introduced a consent-based rape law in 2018;Footnote 11 Denmark adopted a new rape law similar to Sweden’s in January 2021.Footnote 12 Meanwhile, a legislative process in Finland is ongoing that will most probably result in a consent-based rape law,Footnote 13 and Norway has heard demands for a similar move.Footnote 14

This Article looks primarily at the Swedish situation. It seeks to offer some insight into the new Swedish rape law, which is close to an affirmative consent model, as it includes no requirement that complainants express that their participation is nonvoluntary, and the main rule is that passivity on the part of the complainant should not be considered an expression of voluntary participation.Footnote 15 Certainly, Sweden’s law must be seen in the Nordic context, with its tradition of strong welfare states, low sentences, also known as “penal exceptionalism”, and explicit governmental commitment to gender equality.Footnote 16 Despite this, the general conclusions drawn in this article are relevant for discussions of rape and consent, regardless of jurisdiction. My aim is neither to evaluate Sweden’s chosen model for regulating rape, nor to promote alternatives to it. Instead, I aim to show how criminal rape law reform is tied up with an aspiration to sexual education in fields other than the law, and viceversa, how a criminal provision has been framed as a sexual education imperative. While there are sound reasons for decentering criminal justice in providing justice for rape victims,Footnote 17 a premise of this article is that criminalization is one important measure—although it comes with certain limitations—in achieving justice and preventing sexual violence.Footnote 18

My approach—analyzing how a crime is represented in the law—is methodologically inspired by Bacchi’s method, “What’s the problem represented to be?”Footnote 19 Section B lays out the details of this approach. One explicit aim of Sweden’s new rape law was to send “a clear normative message that sex without consent is illegal.”Footnote 20 Section C briefly describes the new law and shows that it suffers from a lack of legal certainty regarding the definition of criminal behavior. The new rape law sends a clear message about what sex should be: Namely, voluntary. The law is less straightforward when it comes to accurately describing the crime. This legal uncertainty is connected to the way that rape is represented as a matter of choice and communication in sexual situations; this is considered in Section D. Section E describes the emergent problem of sexual communication in the disparate spheres of public health, social media campaigns, sexual education, and gender studies. Connecting the dots, Section F sketches out discursive effects of the new framing of rape, while Section G suggests that discussions about where to draw the line for criminal responsibility may benefit from empirical knowledge about how people communicate in sexual encounters.

B. What is Rape Now Represented to Be?

A press release in March 2018 declared that the Swedish Government was proposing the introduction of a new rape law that “states the obvious”, “sex must be voluntary”.Footnote 21 While the new law came as a timely response to the #metoo movement’s call for justice, just a few years earlier it had not been at all obvious that Sweden would or should move towards an affirmative consent model. The new rape law was the result of a process that spanned two decades and included several governmental commissions of inquiry, scholarly debate, and an intense discussion in the media of the advantages and disadvantages of a consent-based rape law.Footnote 22 The reform process took place within a political context in which gender equality concerns increasingly led to addressing violence against women as a matter of criminal justice.Footnote 23 Media coverage of several high-profile rape cases also played an important role in the debate.Footnote 24 This article does not investigate the driving forces behind the reform of the law, but rather, focuses on the effects of representing rape in criminal law as a matter of sex, communication, and choice. The analysis is inspired by Bacchi’s method, “[w]hat’s the problem represented to be?” (hereinafter “WPR”), which involves a social constructionist approach to law and policy and aims to “open up for questioning something that appears natural and obvious.”Footnote 25 This method is used in this article to investigate the seemingly now self-evident notion in crime policy—that sex must be voluntary.

While Bacchi’s approach is designed to analyze problem representations in the context of policy-making processes, I will analyze a representation of a crime, treating legal texts as part of a discourse that produces a certain understanding of what rape is.Footnote 26 Drawing on the work of Smart, law is considered a site of knowledge production that makes claim to truth and has the power to subjugate other discourses around, for instance, sexual violence.Footnote 27 Understanding law as a discourse is useful as it “could help lawyers to recognize the limits of rational chains of arguments and to reflect on different problem formulations, arguments and interpretations.”Footnote 28 My purpose is to investigate the presuppositions and assumptions present in the description of the new rape law.Footnote 29 My analysis consists of a close reading of the preparatory works to the reformed rape law. It focuses on the sections in each document that contain reasons for the reform, considerations regarding the exact formulation of the new law, and the descriptions—so-called explanatory notes—of how the new rape law should be interpreted and applied by legal practitioners and courts.Footnote 30 In performing the text analysis, I have looked at the concepts, dichotomies, situations, and examples that are used to describe the crime.Footnote 31 I pay attention to how the two main subjects in criminal legal discourse—the subject of criminal responsibility, perpetrator/defendant, and the subject of criminal protection, victim/complainant—are described.Footnote 32 The analysis also considers discursive effects in the criminal justice context, by which I mean what effect representing a crime in a certain way has on allocating criminal responsibility.Footnote 33 The WPR approach offers a way to understand representations of crimes in relation to problem representations in discourses outside criminal law and crime policy, for example, the problematization of sexual communication present in late modernity. In this view, the “[o]f [your own] free will” campaign mentioned above not only offers information about the new rape law, but also represents rape itself in a certain way.

C. Legal Uncertainty in the New Rape Law

Until 2018, rape as legally defined in Sweden had to involve either coercion by assault, other violence or threat, or improper exploitation based on the fact that the complainant was in a particularly vulnerable situation due to, for example: Unconsciousness, sleep, grave fear, the influence of alcohol or drugs, illness, bodily injury, or mental disturbance.Footnote 34 The question of the complainant’s consent did, however, play a decisive role without being explicitly part of the old definition, and was used in court practice both in the form of a consent defense by defendants and as a hypothesis of consent applied by the court.Footnote 35 One might therefore imagine that the effect of the shift from the coercion model to the consent model would be small. On the contrary, a review by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brottsförebygganderådet, abbreviated Brå) of court cases after the 2018 reform found that 76 prosecutions for rape, of a total of 362, involved instances that would not have amounted to rape under the old law.Footnote 36

Under the new law, there are three requisite elements for the crime of rape that the prosecution must prove.Footnote 37 The first is that the defendant had sexual intercourse or performed some other sexual actFootnote 38 that in view of the seriousness of the violation is comparable to sexual intercourse. Sexual intercourse is restricted to penile penetration of the vagina. Comparable sexual acts are gender-neutral and include, for example, insertion of the penis into the anus or mouth, or penetration of the vagina or anus with objects or body parts other than the penis. The rape definition also includes situations when the complainant performs sexual acts on themselves or with a third person. The less serious crime of sexual assault exists for sexual acts that are not comparable to sexual intercourse.Footnote 39

Second, to prove criminal responsibility for rape, the prosecution must prove that the person with whom the sexual act was performed did not participate voluntarily. The law specifies situations when participation may never be considered voluntary: (1) if participation is a result of an assault, other violence or a threat of a criminal act, a threat to bring a prosecution against or report another person for an offense, or a threat to give detrimental information about another person; (2) if the perpetrator improperly exploits the fact that the other person is in a particularly vulnerable situation due to unconsciousness, sleep, grave fear, the influence of alcohol or drugs, illness, bodily injury, mental disturbance or otherwise in view of the circumstances; or (3) if the perpetrator induces the other person to participate by seriously abusing their position of dependence on the perpetrator.Footnote 40 If none of the above apply, but participation still was not voluntary, the defendant may be found guilty under the first sentence of the relevant section of law.Footnote 41

I. Nonvoluntary Participation

The precise meaning of nonvoluntary participation was a disputed issue in the legislative process. An official commission of inquiry proposed in 2016 that in order for participation to be considered voluntary, the choice to participate had to be expressed, and only a verbal “yes” or active participation could be interpreted as voluntary participation.Footnote 42 This position drew criticism from several legal bodies to whom the proposal was referred for consideration.Footnote 43 As a result, the draft bill submitted to the Council on Legislation (Lagrådet) excluded the statement that “the choice to participate must be expressed for participation to be considered voluntary” from the legal definition.Footnote 44 The Council on Legislation found that the boundary between a criminal act—nonvoluntary participation—and a lawful act—voluntary participation—was mainly to be determined by the circumstances in the individual case and would be dependent upon individual judges’ normative conceptions regarding what kinds of participation in sexual acts should not be deemed voluntary.Footnote 45 The Council therefore found it not possible to predict in which cases the conditions for criminal responsibility would be fulfilled, and so advised against implementation based on the principle of legality. In response to this criticism, the bill eventually accepted by Parliament instead includes the following sentence; “[w]hen assessing whether participation is voluntary or not, particular consideration is given to whether voluntariness was expressed by word or deed or in some other way.”Footnote 46 The purpose of this sentence was to more clearly demarcate the area of criminalized behavior.

The new rape law may be better understood if considered in the light of the different scenarios of communication described by Hörnle.Footnote 47 A scenario where the complainant communicated that they did not want to participate in a sexual act—"no means no”—is clearly considered to be rape, as communicating a no—verbally or by other means—is a sufficient requirement for criminal responsibility. “Only yes means yes,” or affirmative consent, describes a scenario where the complainant could have communicated that their participation was nonvoluntary but did not do so—and where none of the situations in points one through three enumerated above exist. The Swedish law does not state that a defendant can be held liable for rape solely on the ground that the other person did not say yes. Yet there is no requirement for the complainant to have expressed that their participation was nonvoluntary; a person can still be held liable for rape even when any outward expression of nonvoluntary participation is absent. According to the Bill, the assumption is that persons who participate voluntarily in a sexual act will express their desire to do so, and that the lack of such expression should normally be interpreted as nonvoluntary participation.Footnote 48 The explanatory notes state that in exceptional cases, tacit consent to sexual interaction may be enough to ground voluntariness, but if the complainant denies voluntary participation, it should be required that something exists to suggest consent—for the defendant to avoid conviction.Footnote 49 The Supreme Court of Sweden has stated, in the one rape case it has heard so far concerning the new rape law, that there is “limited room for assessing pure passivity as an expression of a choice to participate in a sexual act.”Footnote 50 The Swedish model may most accurately be described as a modified affirmative consent model: “[O]nly yes means yes—with some exceptions.”

I would contend that the new rape law suffers from a lack of predictability. There is no legal definition of nonvoluntary participation and it is left to the courts to decide in each individual case whether voluntary participation is present.Footnote 51 The explanatory notes in the Bill provide general guidelines for the interpretation and application of the new law.Footnote 52 For instance, the notes say that a person who agrees to participate after prolonged persuasion is participating voluntarily, whereas voluntary participation normally does not exist insituations where a person is unexpectedly assaulted via a sexual act—for example, during a medical examination or in public gatherings.Footnote 53 Despite these guidelines, it is not obvious what behavior, situations, or signs should constitute legally valid expressions of voluntary or nonvoluntary participation. Further, there is room for uncertainty regarding when passivity on the part of the complainant should be interpreted as tacit consent, and when it is a sign of nonvoluntary participation. The supposedly clear message that sex should be voluntary is not so clear-cut when it comes to defining—before a case ends up in court—what rape is.Footnote 54 The explanatory notes use language like “normally” and “exceptional situations” and say that something “may” be a crime, indicating broad scope for discretion. This uncertainty has had consequences for court practice, as the Brå review cited above shows. In one third of new cases that led to an acquittal, the acquittal was owing to the fact that the complainant’s signs of nonvoluntary participation were considered to be too vague.Footnote 55 The same review also shows that case outcome may depend upon individual judges’ subjective perception of what kind of behavior constitutes an expression of sexual interest.Footnote 56 Further, there are difficulties in assessing whether participation was nonvoluntary in cases where clear signs of unwillingness are mixed with more ambivalent expressions that could be interpreted as expressions of voluntariness.Footnote 57 According to the Brå review, more clarity is needed on the kinds of circumstances where signs of voluntary participation should be deemed invalid, thus potentially leading to a rape conviction.Footnote 58

II. Intent and Negligence

Third, to prove criminal responsibility, the prosecution must prove that the defendant acted with criminal intent.Footnote 59 Regarding rape cases and the question of voluntary participation, the intent requirement is fulfilled if the defendant was certain that the complainant’s participation was nonvoluntary. This means that the defendant knew of the circumstances that are required for criminal responsibility for rape—for example—that the complainant did not participate voluntarily, was heavily intoxicated, or participated in the sexual act due to violence. The intent requirement is also fulfilled if the defendant has shown so-called “indifference intent” (likgiltighetsuppsåt). Indifference intent, in brief, means that the defendant appreciated that there was a risk that the complainant was not participating voluntarily—a cognitive status—and was indifferent to whether or not that was true—a volitional status. The updated rape law also introduced the new crime of negligent rape. Negligent rape covers situations where the defendant did not have criminal intent but showed gross negligence in relation to the circumstance that the other person was not participating voluntarily.Footnote 60 Gross negligence includes situations where the defendant appreciated there was a risk—suspected—that the complainant was not participating voluntarily, but nevertheless went through with the sexual act.Footnote 61 Gross negligence also, however, includes situations where the defendant did not actually appreciate such a risk, but should and could have done so. To be held criminally liable for negligent rape in these situations requires that what the defendant could do is something that he or she also ought to do. Further, the defendant’s negligence must be “clearly reprehensible” (klart klandervärd).Footnote 62

Uncertainties exist regarding the mental element. Concerning indifferent intent, there is room for discretion in judging whether the defendant realized the risk that the complainant did not participate voluntarily.Footnote 63 According to the explanatory notes cited above, only negligence that is “clearly reprehensible” should be punished, which leaves considerable scope for interpretation regarding what is blameworthy behavior in sexual situations. The Brå review of court cases shows that written judgments use a variety of formulations to describe the defendant’s understanding, and that difficulties arise when seeking to determine whether the defendant has shown indifference.Footnote 64

The point of this brief account of the new rape law in Sweden is not to evaluate it as either a failure or a success. The number of rape prosecutions increased after the reform by more than the increase in reported rapes.Footnote 65 This indicates, according to the Brå review, that the new rape law facilitated the prosecution of reported cases in the criminal justice system.Footnote 66 In addition, the number of rape convictions has risen significantly—from 190 convictions in year 2017 to 333 convictions in 2019.Footnote 67 According to the review, the most probable explanation for this rise is that the aim of the new law has been fulfilled: Sexual violence that could not be successfully prosecuted under the old law now can be.Footnote 68 My point is to underscore that both at the level of actus reus—whether participation was nonvoluntary—and at the level of mens rea—what the defendant knew or should have known about whether the participation of the other person was voluntary—the law leaves considerable room for interpretation. One might object that court discretion is common in criminal law, and not a problem specific to rape cases. Further, some uncertainty may be resolved with the help of future clarifications from the Supreme Court. I suggest, however, that the problem is also of a different kind. Insofar as the law now represents the crime of rape as a matter of choice and communication in sexual situations, attribution of criminal responsibility necessarily relates to normative assumptions about how people behave and should behave in sexual encounters. This is not entirely new. Rape trials have a history of being saturated with normative and gendered assumptions about female sexuality in particular—and this is regardless of whether the rape laws are based on coercion or consent.Footnote 69 What is new is that the updated definition of rape explicitly refers to normative behavior in sexual situations and implies an educational imperative—sex must be voluntary. Therefore, the uncertainties I have mentioned are better understood if they are not treated solely as a matter of accuracy in a narrow legal sense; I do not consider a more stringent wording of the rape provision the key. Instead, these uncertainties are better considered as part of a broader context in which rape is framed as a problem of sexual communication. The next section describes in more detail how rape is represented in criminal law discourse as a matter of choice and communication in sexual situations.

D. Rape as a Matter of Choice and Communication in Sexual Situations

This section shows that the updated law on rape in Sweden now represents rape as a matter concerning choice and communication between gender-neutral subjects in sexual situations. The subject of criminal protection—the claimant—is expected to make a choice, and this choice is the determining factor for whether a crime has been committed. This characterization of rape tells us what subjects should do to avoid having nonvoluntary sex, but is less explicit regarding the requirements for criminal responsibility.

From the outset, the new legislation positions rape in the context of positive sexuality, where sexuality is described as a natural and pleasurable part of human life.Footnote 70 It draws a boundary between sex on the one hand—which is voluntary, thus positive, good, and valuable—and crime on the other—nonvoluntary, thus negative, bad, and punishable. With crime and sex juxtaposed in this fashion, the way that rape is presented relies on describing what is not a crime. The sexuality on which the law is based is one of equality and mutuality. For example, one point of emphasis is that the concepts used in the legal definition of rape should not reflect inequality in sexual relations,

“Concepts such as allowance and permission are, in our opinion, not entirely successful, as they can to some extent be considered to express an inequality between the parties who participate in sexual relations. What should instead be the starting point is that sexual relations are basically something positive and grounded in reciprocity.”Footnote 71

The updated law also sets rape in relation to an understanding of how people behave and communicate when they have sex. For example, the preparatory works state that sexual relations are seldom preceded by a detailed discussion between the parties about what should happen, and that the sexual act develops gradually through the partners’ actions, for example, through the mutual exchange of kisses, hugs, and caresses.Footnote 72 Just as rape is defined in relation to a conception of what sex is, it also rests on a normative comprehension of what sex should be—namely, mutual and voluntary.Footnote 73 This normative idea of sex is also, as described above, something the legislative reform explicitly aimed to achieve.Footnote 74 Explanations of how to interpret the new definition contain implicit suggestions of how people should behave in sexual situations. For example, “[i]f any participant changes their behavior from being active to becoming passive, there is often reason for other participants to check with them that participation is still voluntary, e.g. by asking an explicit question.”Footnote 75 This passage also exemplifies the way that rape is represented as something that happens in a situation that is already sexual. The Swedish word for “participate,” “delta,” which is used in the criminal definition, means to participate with other people in a collective activity.Footnote 76 Rape is represented as miscommunication in a joint venture that from the outset is sexual.Footnote 77 An exception is rape represented as an unexpected assault in a situation that is not sexual, for example, during a medical examination or during a crowded concert.Footnote 78 To sum up, the law represents rape as something juxtaposed with sex—if the act is not voluntary, it is rape; if it is voluntary, it is sex. The representation of the crime is dependent upon descriptions of sexual acts, situations, and behaviors that are voluntary, and upon subjects involved in a joint sexual activity. The subjects are not gendered, with only a few exceptions.Footnote 79

The focal point for attributing criminal responsibility, moreover, is choice. To be more precise, it is the choice made by the subject of criminal protection that matters. The preparatory works state that the primary good to be protected in sexual offenses is sexual self-determination, along with sexual integrity.Footnote 80 But another aspect of choice is that its presence is a precondition for consent. Representing rape as a matter of sex/not sex implies that the subject of criminal protection must make a decision—to participate or not to participate.Footnote 81 Choice as the key determinant for criminal responsibility builds upon three distinctions.

First, choice is something other than the subject’s inner will, and the subject’s inner will is not decisive for criminal responsibility.Footnote 82 This is motivated by the right to self-determination—one has the right to choose to have sex that one might not want—and the notion that a person who has sex with someone who has expressed that he or she wants to participate should be able to rely on that.Footnote 83 The subject of criminal protection can want one thing but choose the other. This distinction has been described as consensual sex as opposed to wanted sex,Footnote 84 or as positive consent as opposed to constrained consent.Footnote 85

Second, there is the distinction between on the one hand the subject’s choice and on the other hand expressions of that choice, also known as performative consent.Footnote 86 As mentioned above, opinions diverged regarding the governmental commission’s proposal that if the complainant did not express their choice to participate voluntarily in a sexual act, that should be sufficient to ground criminal responsibility for rape. Both positions have in common that they see the new rape law as addressing the problem of what the subject of criminal protection wants, chooses, and expresses. When the documents discuss situations where there is ambivalence regarding whether they should fall under the new definition of rape, those discussions are concerned with a lack of congruity on the part of the subject of criminal protection—when the subject wants one thing, but chooses the other, or expresses neither what they want nor what they choose. One such borderline situation where inner will differs from choice is so-called “tjatsex”, a word used in the Bill whose literal translation is “nag-sex” meaning when a person after much persuasion makes the choice to participate in a sexual act.Footnote 87 Further, the complainant’s passivity appears as a problem when defining rape, indicating an underlying assumption that choice is normally expressed in some way in sexual situations. The right to express choice through passivity, however, is also held to exist,

“A person who is subjected to a sexual act against their will has no responsibility to say no or clearly show their aversion to a sexual act. Also, they have no responsibility to clearly show their desire for sexual intercourse. In the same way that everyone must decide whether he or she wants sexual intercourse, it is part of the sexual right to self-determination to respond to sexual approaches as one wishes to do, including with passivity.”Footnote 88

This passage further indicates that passivity cannot be the absence of choice. It is understood as an expression either of voluntary or of nonvoluntary participation. The passive subject is constructed as a problem because passivity deviates from the presupposition that the subject knows what he or she wants, makes a choice, and expresses that choice.

A third distinction concerns situations where the ability to make a choice is restricted in such a way that criminal responsibility should be attributed. Whereas the old law defined rape in terms of the means used by the subject of criminal responsibility—force, violence, threat, exploitation—these means are still present in the new rape definition, but now as circumstances that restrict the free will of the subject of criminal protection.Footnote 89 Violence and force become intelligible through the lens of voluntary participation, and it is not the violence per se that constitutes rape. For example, concerning acts of violence that do not constitute rape,

“If those who participate in sexual intercourse agree that violence should be included as part of the intercourse, the choice to participate cannot be considered a consequence of the violence. This may be the case e.g. within the framework of so-called BDSM sex.”Footnote 90

In the context of intimate partner violence, too, rape is represented as a matter of the free will of the subject of criminal protection,

“It could be questioned whether persons living under a constant threat of violence in a relationship can be considered to express their free will. At the same time, there may be periods in the relationship without elements of violence or threats. The starting point must, in the Government’s opinion, be that there may be voluntary sexual intercourse even in such relationships.”Footnote 91

Further examples of how the ability to choose is now the foundation for the distinction between sex and crime include the discussions about whether making an offer in exchange for sex limits the subject’s ability to choose freely, and the discussions about situations of deception.Footnote 92

Last, while the updated rape law presumes a subject of criminal protection who expresses his or her choice to engage in a sexual act, it also implies a subject of criminal responsibility who understands what the other person wants and expresses. If the choice of the subject of criminal protection is one key determinant of responsibility, the other key determinant is the ability to comprehend and interpret what the other person wants. The new law, I contend, represents rape as a matter of—failed—communication. The subject of criminal responsibility is expected to explain what made them believe that the other person participated voluntarily.Footnote 93 This subject is also expected to ask questions when in doubt.Footnote 94 Mutual, good, voluntary sexuality requires communication. The ability to communicate is mostly visible in the sections that describe the new crime of negligent rape, which prescribes diligence in sexual situations: “A law based on voluntary participation is founded on the premise that anyone who intends to have sexual intercourse with someone else must ensure that the will to have such intercourse is mutual. Therein lies a requirement for caution."Footnote 95

While largely invisible in sections describing in more detail what amounts to nonvoluntary participation, the subject of criminal responsibility appears the more clearly in sections on intent and negligence. The subject of criminal responsibility is expected to have communication skills and to be diligent enough to understand the other person’s signals and to ask if uncertain.

To conclude, I have shown that Sweden’s new law on rape represents rape as a matter concerning choice and communication between gender-neutral subjects in sexual situations. The subject of criminal protection is expected to make a choice, and this choice is the determining factor for whether a crime has been committed. I suggest that the legal uncertainty pointed out in the previous section may be related to this form of representation. By centering the crime around choice and expression on the part of the subject of criminal protection, the question of when a person is to be held responsible for rape—the distribution of punitive censure—is pushed aside. Characterizing rape in this way tells us what the subject of criminal protection should do to avoid having nonvoluntary sex, but is less explicit regarding what is required for criminal blameworthiness, apart from the fact that the subject of criminal responsibility is expected to have communicative skills and be diligent in sexual situations. Considered in a larger context, I suggest in the following sections that the way rape is represented in the new law relates to the emergent problem of sexual communication that can be found in discourses in society beyond the legal, and that it has a historical background in the shift from a thick to a thin normativity that permeates law and intimate relations in late modernity.

E. The Emergent Problem of Sexual Communication

The current representation of rape in Swedish criminal law discourse relates to an emergent problem of sexual communication described in such disparate spheres as public health, social media campaigns, sexual education, and gender studies research. This problem is characterized by a concern with gray zones in sexual encounters; behavior that does not amount to a crime, nor is good sex, but lands somewhere in between. It captures experiences of sex in these gray zones, previously “unheard within dominant discourses on both sex and sexual violence.”Footnote 96 The 2010 Twitter-initiated #talkaboutit campaign, started by Swedish journalist Johanna Koljonen, is one example of the discourse on gray areas in sexual encounters.Footnote 97 The campaign related to rape in a legal sense, as it was initiated in response to the rape accusations against Julian Assange, but the gray zones were mainly framed as a matter of sexuality rather than criminal violence.Footnote 98 According to Karlsson, the hashtag campaign attempted to find a more capacious language around negative sexual situations and “sought to find discursive room for ambiguous sexual experiences in between choice and coercion.”Footnote 99 The narratives of the campaign partially concerned how to express oneself when subjected to unwanted sexual advances.Footnote 100

The problem of sexual communication is also, I suggest, characterized by an interest in investigating how people do communicate what they want, how they comprehend what other people want in sexual situations, and how such communication can be improved. A recent study conducted by the Swedish Public Health Agency entitled “Sexual Communication, Consent and Health” is one example.Footnote 101 The aim of this study was to gain knowledge about how people communicate whether and how they want to have sex, how they perceive their ability to communicate, and whether that ability has an effect on their well-being.Footnote 102 The new rape law is mentioned as a background to the study, but the study is mainly framed as a matter of sexual and reproductive health.Footnote 103 Another example is Gunnarsson’s interview study in the field of gender studies that focuses on how people express sexual consent. It relates to the new rape law and the concept of voluntary participation, but its aim is to investigate the dynamics of consent in human and social processes.Footnote 104 In addition, and also with reference to the new rape law, Holmström et al. conducted an interview study to investigate how young people in Sweden interpret sexual consent and sexual negotiations, and how they understand the legal imperative that sex must be voluntary.Footnote 105 Further examples are educational projects from nongovernmental organizations such as FattaFootnote 106 and the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education, hereinafter Riksförbundet för Sexuell Upplysning (RFSU),Footnote 107 which offer tools and courses aimed at helping people learn to communicate about sex, express consent, and avoid having sex with someone who does not want to have sex.

Putting the representation of rape in the context of the emergent problem of sexual communication makes visible two discursive effects, which the next section addresses.

F. Towards Choice and Communication in Late Modernity

First, one effect of the way that the new legislation represents rape as gender-neutral and bound up with choice is that it risks rendering invisible the notion of rape as gendered and unilateral violence. In Sweden, rape was strongly framed as a form of male violence against women and an issue of gender inequality in the 1990s.Footnote 108 Although rape is now framed as a gender equality issue in politics at large,Footnote 109 criminal law reforms since the early 2000s have been narrowly concerned with rape from a legal dogmatic perspective and include neither sociological knowledge nor a structural or contextual perspective on sexual violence.Footnote 110 This is true of the most recent reform, and the new legislation intensifies the representation of rape as involving a gender-neutral individual’s choice in sexual situations. This portrayal of rape is at odds with feminist understandings that conceptualize sexual violence as part of the continuum of violence against women.Footnote 111 Further, representing rape as something that occurs between equal and non-gendered individuals when they are engaged in the mutual enterprise of having sex is, is turning rape into an agentless mistake rather than an act of unilateral violence.Footnote 112 The critique against the criminal law conceptualization of sexual violence, in short, is that law is particularly poor at comprehending and taking into consideration the structural violence against women of which rape forms a part.Footnote 113 Whereas rape in criminal law discourse is represented as a gender-neutral, individualistic problem, the problem of sexual communication includes considering the way gender norms influence the ability to communicate in sexual situations and stresses the need to problematize normative assumptions about gender to improve sexual communication. A tension exists, however, regarding to what extent sexual violations should be understood as a matter of a structural power hierarchy that subordinates women and privileges male sexuality.Footnote 114 Therefore, the emergent problem of sexual communication can also be seen as a move away from conceptualizing rape as violence against women.

The intersections of gender, sexuality, and power in understanding sexual violence have been thoroughly theorized and my intention here is not to further contribute to this discussion, save to point out that the issue is complex.Footnote 115 In the effort to comprehend the problem of sexual communication and its relation to the representation of rape in criminal law discourse, a way forward might be to consider the role of choice, consent, and communication in late modernity in a wider sense. Illouz argues that in late modernity, choice “is the chief trope under which the self and the will in liberal polities are organized,” and to have a self is to exercise choice.Footnote 116 The new rape law and the problem of sexual communication are each part of the organization of intimate relationships in late modern capitalist societies, where choice and consent are the dominant ethical discourse.Footnote 117 The sexual liberation movement and the feminist striving for gender equality both foreground choice and consent.Footnote 118 Against this background, the shift to consent-based rape laws in Sweden and elsewhere is simultaneously a feminist triumph and an extension of late capitalism consumer rationality. In addition, the focus on communication can be understood against the background of emotional capitalism, where the ability to communicate in sexual situations can be understood as a form of an emotional capital that has emerged as a new form of capital in late modernity.Footnote 119

Second, while the legislative materials analyzed in Section D aim at constructing clear and unambiguous legal concepts—i.e. nonvoluntary participation—the problem of sexual communication aims rather at embracing complexity and brings to the fore nuances and ambivalence in sexual encounters. The aim of the #talkaboutit campaign was to problematize the black-and-white distinction between rape and sex and to make the gray zones visible. The study by the Public Health Agency emphasizes that sexual consent can be complex and context-dependent, and suggests doing further research into these complexities and the norms surrounding sexual communication.Footnote 120 Gunnarsson’s study underscores that the process of consent is—the same time—very simple and very complex, and suggests further collective reflections on ambiguousness in sexual relations.Footnote 121 A similar conclusion was reached by Holmström et al.Footnote 122 Obviously, there is a contradiction here. If sexual communication is complex and if it is difficult to pin down the exact difference between rape and sex, it seems futile to try to achieve a proper definition of rape in criminal law.

This contradiction can be further explored by considering sex offense laws and morality in the longer perspective. The modern history of sexual offenses—the ninetenth to twenty-first centuries—in Swedish criminal law is usually presented as a narrative where the primary good has changed from public morality to individual integrity.Footnote 123 The law on sexual offenses has gradually improved since the Penal Code of 1864 in such a way that the legal protection of sexual integrity has become increasingly comprehensive—for example, the definition of rape has expanded considerably—while crimes against decency—for example, fornication against nature—have been abolished. In a previous work I have shown that along with this development, sexuality also became something positive and worthy of protection, and a part of the subject’s inner personality.Footnote 124 This means that sexual criminal offenses had to be understood in relation to this lustful, mutual, erotic sexuality. The way rape is represented as a matter of sex in the most recent rape law reform is therefore not something entirely new or different; instead, it is the result of a lengthy process in the modern history of sexual offenses. What is different from before is that the reformed rape legislation now explicitly frames rape as a matter of sex, choice, and communication.

The narrative in which morality has been replaced by the individual’s sexual integrity and sexual self-determination corresponds with a larger shift from a thick normativity to a thin, procedural normativity that governs intimate relations in late modernity.Footnote 125 Thick normativity, says Illouz,

“contains elaborate stories and prescriptions that define actions in terms of good and bad, immoral and moral, pure and impure, shameful and commendable, virtuous and vile, and thus connects human behavior to cultural cosmologies, large collective stories . . . that contain definite conceptions of the good and the bad, the moral and the immoral.”Footnote 126

Thin normativity, on the other hand, “gives individuals the right to decide about the moral content of their preferences and focuses on the rules and procedures to secure respect for the psychic and bodily autonomy of the individual.”Footnote 127 Thin normativity is silent “on the moral valence of actions, and evaluates them in reference to the degree to which they respect the subject’s autonomy and capacity to experience pleasure.”Footnote 128 This thin normativity, I suggest, is apparent both in criminal law discourse and in how the problem of sexual communication is portrayed. But it is rather inadequate for deciding when to attribute blameworthiness. As many have shown, consent—or procedural normativity—is a poor concept when it comes to defining blameworthy behavior, or understanding sexual violence, both in the legal context and elsewhere.Footnote 129 I suggest that the role of criminal law in providing guidelines for sexual behavior needs to be explored further. Criminal legal regulation of rape is used to put forward the normative stance that sex should be voluntary. The increasing engagement of criminal law as a response to sexual violence that we have witnessed in many jurisdictions can, against the background of the current state of thin normativity, be a sign of a certain expectation of criminal law to, in Illouz’s words quoted above, define actions in terms of good and bad, immoral and moral.

G. Connecting Legal Uncertainty with Sexual Communication

The effects I have described above engender more questions than answers and concern theoretical and practical challenges regarding the interplay between criminalization, feminist activism and gender politics, and the role of rape laws in sexual educational projects. Rape laws that center the choice and consent of the subject of criminal protection—whether in terms of a “no means no” model or an “only yes means yes” model—are here to stay, in Sweden and elsewhere. The exercise of choice is too central to the very understanding of the self in late modernity to be left out of rape crime policy. In addition, the emergent problem of sexual communication is a discursive framing of rape that is related to how individuals perceive and express communication and violations in sexual encounters. Sexual communication, too, is central for the very understanding of the self in late modernity.

At the same time, the legal uncertainty pointed out in Section C must not be overlooked. It is problematic because it goes against the fundamental rule of law principle that criminal provisions must be predictable. In addition, it matters for crime prevention. As Larcombe puts it, “[i]f the criminal law cannot communicate and maintain clear and accepted norms, it has no chance of guiding conduct and influencing community attitudes and values so as to prevent sexual violence.”Footnote 130 Acknowledging these problems, I insist that the uncertainty that accompanies the new rape law is not in itself an argument against a rape definition based on non-voluntariness. Neither is the solution a more refined statutory wording.Footnote 131 The great scope for discretion that the new rape law has created requires, in a more explicit way than before, that criminal justice practitioners have some kind of common conception of how people behave in sexual situations and a normative comprehension of what constitutes blameworthy—and acceptable—behavior in sexual encounters. The courts must provide meaning to concepts such as choice, consent, and communication to accurately attribute responsibility for rape in individual cases. To punish individuals for transgressing criminal legal norms may be viewed as illegitimate if the rape law departs from accepted social norms.Footnote 132 The emergent problem of sexual communication may be conceived as a search for substantial knowledge on how people behave in sexual situations and what the accepted social norms are, and, if considered, may therefore provide normative thickness to criminal law.

I suggest that research, policy, and legal decision making should take into account the interrelation between criminal legal regulation of rape and knowledge about sexual communication. Consider the following examples. When asked “[h]ow did you show that you wanted to have sex with the person you last had sex with?”, the majority answered that they did so verbally and/or with body language and eye contact.Footnote 133 However, eleven percent of the respondents answered that they did not know whether or how they showed this and three percent answered “did not show.”Footnote 134 While a majority of the respondents stated that they have the ability to communicate to a partner whether, when, and how they want to have sex—fifty-six percent—ten percent answered that their communication skills do not work.Footnote 135 How does criminal law deal with an inability to communicate? Conversely, can the new rape law enhance individuals’ ability to communicate in sexual situations? Further, Gunnarsson’s study suggest that whether a person perceives a sexual transgression as a violation depends to some extent upon how the person responsible for the transgression deals with the mistake in terms of correction and repair.Footnote 136 To what extent does criminal law accommodate mistakes in sexual situations that have been corrected? Does the new rape law facilitate for individuals to correct and repair transgressions in sexual situations? Further, if communication in sexual situations is a skill that we need to learn, as Fatta and RFSU suggest, does criminal law consider the extent to which young people, especially, have been given the opportunity to learn to communicate and tune in to other people? There are no easy answers to these questions, but I contend that a rape law that addresses rape as a matter of choice and communication in sexual situations and sends the normative message that sex must be voluntary needs to consider this kind of knowledge to attribute blameworthiness with certainty and legitimacy.

H. To Conclude

In criminal law discourse, rape is represented as a problem that has to do with sex, choice, and communication. This characterization of rape relates to the emergent problem of sexual communication within disparate spheres such as governmental public health, social media campaigns, sexual education, and gender studies research. Both can also be related to a discursive reframing of rape that has taken place in Sweden in recent decades—a move from addressing rape as gendered violence towards framing rape as a question of individual sexual integrity and self-determination. I have further suggested that the centrality of choice and communication is part of a move from thick normativity to a thin one, and that choice and communication are crucial for the very construction of the self in late modernity. It is difficult not to concur with the message sent by the Swedish government when the new rape law was introduced that “sex must be voluntary.” However, the new rape definition comes with uncertainties that need to be addressed further, both to overcome the pedagogical challenge of explaining in more detail what behavior amounts to a crime and to accurately attribute criminal blameworthiness in individual cases.

The current uncertainty is not only a problem for future defendants, but also for victims of sexual violence and for crime prevention at large. As policy has moved towards governing the gray zones of sex with criminal law, crime policy may benefit from studies about sexual communication to accurately attribute criminal responsibility. As mentioned in the introduction, there are several jurisdictions where rape reform is set to happen soon. A lesson from Sweden is that future legal reforms should put less effort into describing what the subject of criminal protection should do to avoid having nonvoluntary sex, and pay more attention to defining the kind of behavior by the subject of criminal responsibility that is worthy of criminal censure and punishment. To do so, the legislative process may benefit from knowledge of how people communicate in sexual situations and must not address the problem of rape as solely a legal positivistic quest for the most accurate legal wording.