The annual consumption of energy drink products in 2013 exceeded 5·8 billion litres in over 160 countries( Reference Bailey, Saldanha and Gahche 1 ). Available nutrition surveillance surveys in Europe give a very wide range of consumption levels, 8–30 % in adults and 1·6–68 % in teenagers; and point to a young, mainly male consumer( Reference Bailey, Saldanha and Gahche 1 – Reference Malik, Pan and Willett 4 ).

While no standard definition exists, energy drinks are commonly understood to be non-alcoholic drinks which contain caffeine as a main ingredient and which are marketed as a stimulant to improve energy levels and performance( Reference Zucconia, Volpatoa and Adinolfia 5 ). Adults tend to use this type of beverage as a mixer with alcohol but it is increasingly being consumed by children and adolescents( Reference Breda, Whiting and Encarnação 6 ). A recent European review on energy drinks raised concerns about their caffeine and sugar content( Reference Breda, Whiting and Encarnação 6 ), with products typically containing a caffeine concentration of 80 mg per 250 ml can.

Excess caffeine consumption can lead to anxiety, insomnia and gastrointestinal upset in adults( Reference Bedi, Dewan and Gupta 7 ). The effects have not been studied in children or adolescents for ethical reasons, despite these beverages’ availability. While the European Food Safety Authority has set recommended safe limits for caffeine consumption in adults, it has not done so for children or adolescents. It has, however, raised concerns over the acute effects of caffeine consumption from energy drinks and the risk of adverse health effects in adolescents and adults involving the cardiovascular and central nervous systems, particularly when consumed over a short period, at high doses, and in combination with alcohol and/or physical exercise( 2 ).

Energy drinks are classed as sugar-sweetened beverages, which have been linked to weight gain and obesity in both adults and children( Reference DeBoer, Scharf and Demmer 3 , Reference Malik, Pan and Willett 4 ). Currently one in four children and two in three adults in Ireland are overweight or obese( Reference Layte and McCrory 8 , 9 ). In addition, the sugar content has also been linked to dental erosion( Reference Hasselkvist, Johansson and Johansson 10 , Reference Marshall, Levy and Broffitt 11 ), with energy drink consumption associated with a 2·4-fold increase in dental erosion( Reference Li, Zou and Ding 12 ).

The island of Ireland consists of two jurisdictions: the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. The most recent review of energy drinks in the Republic of Ireland was conducted in 2002( 13 ), where ten products were identified. As energy drinks have become more mainstreamed in the intervening decade, we considered it important to update that survey. The availability of energy drinks in Northern Ireland has not been explored previously. The aim of the present research was to: (i) assess the availability of energy drinks on the island of Ireland (both jurisdictions); (ii) document their caffeine content; (iii) document their sugar content; (iv) define what category of Food Standards Agency label each drink would receive for sugar content; and (v) determine how many of these products meet the EU criteria for highly caffeinated products.

Methods

Energy drinks criteria

For the purpose of the current study, energy drinks are defined as ‘non-alcoholic drinks which contain caffeine as a main ingredient and which are marketed as a stimulant to improve energy levels and performance’( Reference Zucconia, Volpatoa and Adinolfia 5 ). Only products that met this definition were included. Where caffeine was included as flavouring these products were excluded from analysis. Sports drinks and other sugar-sweetened beverages were also excluded as they do not contain caffeine as a main ingredient.

Supermarkets

Products were purchased from six supermarkets in the Republic of Ireland (Tesco, Dunnes Stores, Spar, Centra, Lidl and Aldi) and six supermarkets in Northern Ireland (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Spar, Mace, Lidl and Iceland).

Data collection

All available energy drink products were purchased in February 2015. Brand name, price, volume, price promotion, health messages and caffeine content were recorded for each product. Where information on nutrient content could not be obtained from the label, this information was obtained from the official brand website. Only single-serve products, as sold, have been included in the analysis (e.g. a 330 ml can or a 500 ml bottle).

All information collected was electronically recorded and double-checked by two researchers.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22. Those drinks that did not report caffeine or sugar content were not included in the analysis. Mean values are reported for caffeine and sugar content. Regular and diet versions of products were analysed separately for sugar content.

Food Standards Agency front-of-pack labelling

The Food Standards Agency( 14 ) has issued guidelines on front-of-pack traffic light labelling for processed products. The categories are outlined below. All purchased products were categorised based on this.

EU-defined highly caffeinated products

The EU threshold for drinks to be considered highly caffeinated and to be labelled as such is ≥150 mg/l( 15 ). All purchased products were compared with this threshold.

Results

Availability

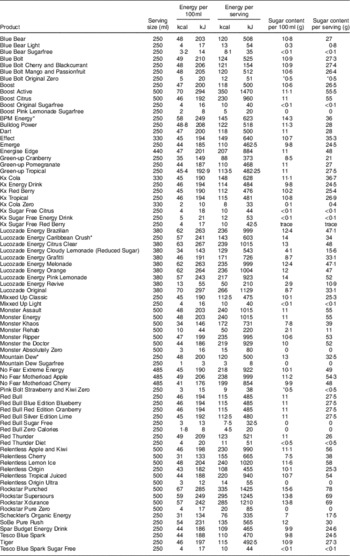

In total, seventy-eight energy drinks were identified. There were sixty-five products available in Northern Ireland and thirty-nine in the Republic of Ireland (twenty-six products in common). No energy drink ‘shots’ or alcohol and energy drink premixes were identified. There was a range of serving sizes from 250 to 500 ml with an average serving size of 353 ml. Table 1 details all products included in the analysis, along with the sugar and caffeine content per 100 ml and per serving of each.

Table 1 Brands purchased and their sugar and caffeine content per 100 ml and per serving; cross-sectional survey of energy drinks (n 78) available from six supermarkets in Northern Ireland and six supermarkets in the Republic of Ireland, February 2015

* These drinks are sold as 500ml bottles; however, the label states a serving as 250ml.

Caffeine content

All products purchased contained caffeine as an ingredient; however, only 80 % (n 67) of these noted the actual amount on the label. Mean values were calculated based on this group.

The mean caffeine content per 100 ml was 30·7 mg, with a range of 14 to 35 mg. The majority of products (88 %) had a caffeine content of between 30 and 32 mg per 100 ml. When looking at the caffeine content per serving size, the range of variation was large: 35 to 160 mg. The mean caffeine content per serving was 102·2 mg (Table 2).

Table 2 Caffeine content of surveyed energy drinks (n 67) from six supermarkets in Northern Ireland and six supermarkets in the Republic of Ireland, February 2015

Sugar content

Of the seventy-eight products, fifty-nine were full sugar/regular and nineteen were diet/light/sugar-free. The average sugar content per 100 ml for regular energy drinks was 10·6 g, with a range of 2·9 to 15·6 g. Per serving there was a mean of 37 g of sugar (Table 3). The sugar and energy content of the diet versions was minimal (mean: 0·1 g sugar/100 ml and 0·17 g sugar/serving).

Table 3 Sugar content of regular versions of surveyed energy drinks (n 59) from six supermarkets in Northern Ireland and six supermarkets in the Republic of Ireland, February 2015

Front-of-pack labelling

If displaying front-of-pack labelling, fifty-seven of the fifty-nine regular-version energy drinks would receive a Food Standards Agency( 14 ) ‘red’ colour-coded label for sugars for a serving as sold, one out of the fifty-nine products would receive an ‘amber’ colour-coded label and one would merit a ‘green’ colour-coded label. All diet versions would receive a ‘green’ label.

Highly caffeinated products

All sixty-seven of the products included met the EU criterion and can be defined as a highly caffeinated product.

Discussion

Seventy-eight energy drinks were identified on the island of Ireland, a major increase from the ten products previously reported in the Republic of Ireland in 2002( 13 ). This reflects global trends towards an increase in products and market shares( Reference Bailey, Saldanha and Gahche 1 , Reference Morenga, Mallard and Mann 16 ). The package size ranged from 250 to 500 ml, and this, understandably, had a significant impact on the caffeine and sugar content.

All (n 67) of the energy drinks met the definition for highly caffeinated products (≥150 mg/l). The mean caffeine content per serving was 102·2 mg, some products contained as much as 160 mg per serving. For comparison, an average 200 ml cup of filtered coffee contains 90 mg, a 200 ml cup of black tea contains 50 mg and a 500 ml bottle of diet coke contains 64 mg( 2 ). There is a higher mean level of caffeine in the products documented in the current survey than in those available in 2002( 13 ).

The European Food Safety Authority has advised that a single dose of up to 200 mg caffeine for an average 70 kg adult is unlikely to cause clinically harmful changes. It has also concluded that daily caffeine intake from all sources up to 400 mg is safe for adults (excluding pregnant women)( 2 ). However, it raised concerns about the quantity which is safe for children and adolescents and currently no limits are set due to insufficient data. Energy drinks are high-caffeine products and five 250 ml cans or two 500 ml cans can exceed these recommended safe limits. That does not count other caffeine sources such as tea or coffee consumed during the day. Due to the high availability of these products and the substantial increase in range since 2002 in Ireland, it is important that guidelines be developed to inform safe levels of caffeine intake for children and adolescents.

These energy drinks contained sugar levels comparable to other mainstream sugar-sweetened beverages, which have been linked to weight gain and obesity in children, adolescents and adults( Reference Malik, Pan and Willett 4 , 9 ). Due to the varying serving sizes of these products, sugar content ranged from 10·9 to 78 g. The sugar-containing drinks surveyed contained an average of 37 g of sugar per serving; this is more than 9 teaspoons of sugar per serving (calculated using 4 g per teaspoon). The WHO has recommended that free sugars contribute no more than 10 % of total energy to the diet, with a further reduction to below 5 % providing additional health benefits. The average energy drink surveyed here equated to 7·5 % of the total daily energy intake for the average adult (based on an intake of 8368 kJ (2000 kcal)), exceeding the 5 % ideal and nearing the 10 % recommended free sugars intake. This represents the mean sugar content; some products contained up to 78 g sugar per serving, equating to almost 20 teaspoons of sugar and representing almost 16 % of the total daily energy intake for a 8368 kJ (2000 kcal) diet.

The EU action plan on childhood obesity 2014–2020( 17 ) aims to halt the rise in overweight and obesity in children and young people aged 0–18 years by 2020. All member states are working to achieve this by focusing on eight key areas including restricting marketing and advertising to children, promoting healthier environments and making the healthy option the easier option. Taxation on sugar-sweetened beverages has been agreed as part of a government programme (‘A Healthy Weight for Ireland’)( 18 ) in the Republic of Ireland, which may help to decrease consumption and impact weight positively. Due to their popularity and unrestricted availability, energy drinks are easily accessible to younger children. Voluntary codes or legislation to decrease consumption in youth or restrict sale of these products could be an additional important step.

The current research generated considerable interest in the Irish media with twenty interviews, twenty additional broadcast media reports and 173 media alerts over a 3-month period. It is clear that there is an interest and awareness gap here that needs addressing. Interventions to highlight the health risks that energy drinks pose are recommended.

Limitations

We acknowledge a number of limitations to the present study. Only energy drinks available in surveyed supermarket chains were recorded and there may be other products available to the public in smaller independent stores. Brands and products are changing constantly, with new varieties being introduced and products being reformulated or discontinued, therefore our survey findings apply only to the products available in the time period of sampling (February 2015). We relied on the accuracy of the data provided on the label in our analysis. In addition, the serving size of energy drinks differed grossly with minimum volumes of 250 ml and maximum values of 500 ml; this had an impact on all nutritional analyses per serving. However, having this range within one data set is realistic as energy drinks typically are consumed per can.

Conclusion

The results of the present study serve to document the caffeine and sugar content of energy drinks sold on the island of Ireland. Findings show that energy drinks are freely available in supermarkets and other retail outlets. All products surveyed here can be defined as highly caffeinated products. The caffeine content has potential health issues, particularly in children and adolescents for whom safe limits have not been determined. The study findings support the policy recommendations made in Europe by Breda et al.( Reference Breda, Whiting and Encarnação 6 ) to establish an evidence-based, upper limit for the amount of caffeine allowed in a single serving of any drink and to restrict sales to children and adolescents due to the potentially harmful adverse and developmental effects. Further we recommend the development of guidelines regarding safe levels of caffeine consumption in children and adolescents.

Energy drinks also contribute substantial quantities of sugar to the diet, approximately 37 g per serving, with some products containing as much as 78 g per serving. In a country where rates of obesity are increasing, as they are globally, there is a need to highlight the contribution that these products could make to weight gain. The high sugar content found in the products available in Ireland also has implications for dental health, causing dental erosion and tooth decay. Interventions are required to highlight the dangers of energy drinks to consumers.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: C.F.-N. conceived of the idea and developed the research question; L.K. and S.G. designed the study, collected and analysed the data; C.B. and J.C.F.S. reviewed the data; L.K. wrote the manuscript; C.F.-N., S.G., C.B. and J.C.F.S. reviewed and contributed to the article. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.