Introduction

In February 1978, the young Arsenal fan Colin Ward travelled to Anfield to watch the first leg of the League Cup semi-final against Liverpool. Arsenal would lose the match 2–1 but a disappointing result was to be the least of Colin's worries upon exiting the Anfield Road End. Caught in the midst of escalating crowd disorder in the surrounding streets, safely reaching Lime Street Station proved far more troublesome. Ward recalled that:

Outside in the narrow streets it was chaos…we turned right into the road leading up to the Kop, the rows of terraced houses silhouetted against the night sky by the one remaining street lamp that had not been smashed. The road looked dark and forbidding. I heard a roar and the Arsenal fans in front of me turned back. I could see fear and panic on their faces…I ran straight through a hedge into a front garden and then cleared two more gardens…I was so frightened I could hardly breathe, let alone think. I decided to strike out on my own and head up the street towards the Kop…I just kept walking and miraculously, no one hit me.Footnote 1

Two more mêlées and a delicate negotiation of Liverpool's inner city would be necessary before Ward reached Lime Street. His account of that unnerving evening provides an acute example of the temporary yet dramatic changes that football could impose upon the post-war city. As Britain's urban crisis unfolded and the spectre of hooliganism increasingly dominated discussions regarding the national game from the late 1960s onwards, stadiums would come to hold a uniquely marginal place in the urban imagination and the public psyche – stigmatized as points of disorder and violence, where disdained social activities were undertaken by deviant populations in the shabby and dilapidated areas of Britain's crumbling cities. Shaped by disaster and disorder in equal measure, it was a process that would by extension settle on the mostly working-class populations that attended fixtures and, crucially, the urban areas that surrounded many of Britain's major stadiums.

The unsightly events described around Anfield were thoroughly emplaced, played out in interaction between supporters, the stadium and the surrounding city. Two years later, a report from Merseyside Police's Public Relations department simultaneously framed their analysis of supporter conduct within the boundaries of class and urban decline, commenting that:

Even on their best behaviour football crowds are never going to sound or look like the parade on the lawns of Ascot. They will always have more vinegar than Chanel. The average fan is naturally tough and accustomed to a level of aggressive conduct in the everyday life of our large cities and conurbations; something which is probably little known on the cricket ground or the racecourse.Footnote 2

Recent scholarship has used the material transformations experienced by post-war British cities as a means through which to explore social and cultural change.Footnote 3 This article advances this area of study in two ways. First, it examines how football-related disorder in Liverpool informed perceptions of urban decline and social malaise and investigates how those perceptions affected the lived experiences of inner-city populations. Worsening spectator behaviour from the early 1960s onwards was partly driven by urban renewal programmes, whereas the temporary atmospheres of disorder summoned by unruly crowds ensured that the city's stadiums became some of the most acute points of its urban crisis; a central contributory factor in the perceived social and moral breakdown of the inner city and its creation as, in the words of Jacquelin Burgess, ‘an alien place, separate and isolated, located outside white, middle-class values and environments’.Footnote 4 Secondly, in tracing the increasing level of government attention to stadiums like Anfield and Goodison Park and in the regulation of supporters’ behaviour, this article demonstrates how the resulting promotion of a range of aggressive architectural policies both reflected and further encouraged trends towards the micro-management and policing of problematic urban spaces more broadly in the late twentieth century. The changing materiality of the stadium would have significant, although often unintended, consequences for supporters and inner-city communities in Liverpool as disorderly behaviour once seen on the terraces instead became common on nearby streets. Hooligans, the police and local communities therefore became implicated in a struggle over the use and control of a deteriorating urban form; the crisis within British football converging upon the crisis within the British city. Indeed, while many of the wider problems and proposed solutions to urban policing and public order were formulated in and around especially violent and problematic places like stadiums, by the late twentieth century their wider application as a necessary means of governing urban spaces had become well established.

With a post-war history defined by sporting excellence and drastic urban change, Liverpool provides an excellent case-study from which to investigate this process. As described by Aaron Andrews, the city stands as a paradoxical archetype of the de-industrializing city, a symbolic example of wider national experiences in tabula rasa modernist urban planning, piecemeal and gimcrack implementation and a subsequent decline defined by unemployment, depopulation and dereliction so that by 1981 Lord Esher suggested that Liverpool provided the locus classicus of inner-city collapse.Footnote 5 Astonishing sporting success occurred alongside urban decline, ensuring that football remained a central aspect of Liverpool's society and culture. Between 1960 and 1990, the city amassed 36 domestic and European league and cup titles. In his 1968 account of the national sport, the journalist Arthur Hopcraft noted that ‘more than any other English city, Liverpool experiences its hope and its shame through football’.Footnote 6 When asked if football mattered too much on Merseyside, the city council's deputy leader, Derek Hatton, compared the question to asking if mice cared too much about cheese.Footnote 7 Boasting two of the country's principal teams brought large numbers of people into regular contact with the urban fabric – over two million in 1978, with average weekly attendances totalling 46,400 at Anfield and 35,500 at Goodison.Footnote 8 Situated in the heart of Liverpool's inner city and separated by less than a mile, Anfield and Goodison Park (home to Liverpool FC and Everton FC, respectively) provided two monumental landmarks in the city's physical and mental geography. Simon Inglis’ descriptions from 1983 portray each stadium as thoroughly immersed within Liverpool. Hemmed in on three sides and with a church pressed into the corner of the ground, Inglis likened Goodison Park to a gaunt cathedral among low terraced houses.Footnote 9 Of Anfield, Inglis suggested that the experience began in the surrounding streets; a ‘particularly disorientating approach’ in which ‘all of the houses gradually seem to be decked in red and white’.Footnote 10

Focusing on these urban spaces is important, particularly given that the socio-cultural characteristics of football stadiums are often overlooked and under-researched within the context of the history of the post-war city and the urban crisis. As sites capable of attracting substantial numbers of people to singular locations for the creation and consumption of cultural spectacle, focusing on sport and stadiums help to draw wider conclusions regarding the spatial and social practices of urban life, highlighting how certain spaces acted as vehicles through which notions of crisis materialized; enlisted agents shaping and informing wider cultural discourses in the national psyche. In analysing the Department of the Environment's Inner Area Studies, Otto Saumarez Smith correctly observed that the inner city of the 1970s had become ‘a spatially materialized locus for all that was perceived to have gone wrong with Britain's state and society’.Footnote 11 By utilizing a wide variety of source material – including oral histories, memoirs, media representations and local archival sources – to investigate an overlooked space, this article traces the function of disorder through a specific urban setting, shifts the focus away from studies of state-led approaches to urban decline and opens newer perspectives that focus on the interaction between the political and cultural construction of the inner city and the identities and experiences of individuals who lived within its boundaries. In scrutinizing precisely where the urban crisis and its concurrent anxieties appeared manifest and in tracing how it interacted with the experiential understandings of local communities, this article demonstrates how the idea of an inner-city crisis grew up around the negative representations of certain material spaces and the emplacement of discursive constructs within them, highlighting the diverse and varied ways in which individuals used supposedly problematic urban spaces in late twentieth-century Britain.

Urban renewal, football disorder and the stadium

The mid-1960s were in many respects a high-water mark for Liverpool; widely regarded as a global cultural mecca in the wake of Merseybeat's transatlantic success and with municipal renewal programmes predicting an imminent transformation of the city's nineteenth-century fabric into a modern urban area boldly looking forward into the twenty-first.Footnote 12 Football followed suit, with three First Division titles, two FA Cups and two Charity Shields returning to the city between 1962 and 1966 and average attendances shy of 50,000. However, alongside regular sporting success emerged the growing problem of public order within Anfield and Goodison, so much so that each were increasingly viewed as the city's most acute and challenging points of governance.

Writing in January 1964, Pat Collins described the match-day scene at Goodison as one of prowling plainclothes detectives, volleys of flying cans and bottles and police dogs stalking the edge of the pitch.Footnote 13 Collins’ article came soon after Everton had hosted Glasgow Rangers, a raucous and ill-tempered affair in which the Liverpool Daily Post commented how nervous club officials – who had posted warning notices around the ground voicing the FA's displeasure at recent crowd conduct – were dismayed to see missiles flung onto the pitch as the match unfolded.Footnote 14 Over the course of that particular season, Everton supporters would collect an assortment of unwelcome headlines, including for throwing a dart at an opposing goalkeeper, a stone at an opposing manager and attacking the referee.Footnote 15 Matters appeared to hit a new low in November 1964, when 43,000 supporters packed into Goodison to watch Everton host newly promoted Leeds United. An expectant audience waited just four minutes to witness Everton left-back Sandy Brown dismissed for punching Johnny Giles following a chest-high tackle from Leeds’ diminutive midfielder, thereby setting the tone of what was to follow. Players threw themselves into tackles and scuffles alike. An enraged crowd, baying for retribution, rained missiles onto the pitch. Players were spat at if they ventured too close to the touchline. One aggrieved supporter even invaded the pitch to remonstrate with Leeds’ tough-tackling midfielder, Billy Bremner. After a thirty-eighth minute tackle left Everton's Derek Temple being stretchered off unconscious, the beleaguered referee decided to halt proceedings and march the remaining 20 players – none of whom had been booked – into their dressing rooms.Footnote 16 When the match restarted shortly afterwards, the visitors left Goodison with a victory, albeit only after eight players had sustained injuries and the Liverpool and Bootle Constabulary's Mounted Division had dispersed irate crowds congregating in the surrounding streets. Even with the Goodison crowd's tempestuous reputation, the level of violence on display shocked the national press; the Sunday Express described the fixture as a ‘wild and sickening exhibition’; the Guardian pondered whether the collective irresponsibility of the players outweighed the ‘disgusting’ behaviour of the crowd; the Daily Mail insisted that the gates at Goodison be shut for a month.Footnote 17 Similar scenes were witnessed at Anfield. A fixture against Glasgow Celtic in April 1966, for example, was scarred by crowd disorder that left around 100 spectators injured and press photographers ‘running for their lives’.Footnote 18 Little wonder that the Daily Mirror dubbed supporters on Merseyside as ‘the roughest, rowdiest rabble who watch British soccer’.Footnote 19

As a city with some of the most acute urban problems in Britain and with a long-standing reputation as a tough, working-class port with identities shaped by transient and casual patterns of employment, Liverpool's crowds were an obvious, if predictable, target of national attention. However, what had been christened as the ‘Battle of Goodison Park’ appeared as part of a wider trend of disorder in British football in the mid-1960s, with displays of a similar nature reported to a greater or lesser extent across the country. Contemporary commentators and subsequent analyses linked increasing violence to the growing personal autonomy and leisure opportunities afforded to young people by post-war affluence, a process in which youth culture, juvenile delinquency and the teenager were framed as a pressing social problem.Footnote 20 Less well recognized was how escalating terrace disorder was instigated by changes to the very structure and demography of British cities from the 1950s onwards. The nation's urban renewal programmes and subsequent population shifts – which, as Simon Gunn has observed, were innocent of people's complex relations to time, space and place – were largely focused on the inner-city neighbourhoods that surrounded stadiums.Footnote 21 Shifting youth cultures therefore coalesced with renewal programmes that were blind to the pre-existing social order of the city and to the deep links between working-class communities and collective neighbourhood associations such as football clubs. The consequences for the nature of spectatorship were significant. In their 1970s ethnography of Arsenal's North Bank stand, David Robins and Philip Cohen, for example, concluded that the ‘mass deportation of families’, often to the suburbs of Uxbridge, Elstree or Borehamwood, ‘opened up a space for kids on the terraces’.Footnote 22 Robins and Cohen traced how loose affiliations of youth – generally more vocal and aggressive in their support and tending to gather en masse – increasingly watched from fixed locations within the stadium. More often than not, youth gangs staked their claim to the terraces directly behind the goals in a process that heightened notions of territoriality within the stadium and led to the development of informal home and away ‘ends’.

Processes underway in north London were also afoot in Liverpool. All four of the city's central wards recorded a 45 per cent or more decrease in occupied housing between 1961 and 1971 as dispersal programmes uprooted communities to the outer estates of Kirkby, Speke, Cantril Farm and Netherley.Footnote 23 With low levels of car ownership – just three in ten households on Cantril Farm in 1977, for example – and sporadic public transport options reducing the mobility of dispersed communities, a variety of local testimonies suggest that gaps left by working-age men were at least partially filled by youth gangs.Footnote 24 Interviewed by Robins in 1984, one Liverpool supporter commented how ‘there used to be less trouble with the Kop because there was older men mixed in with the kids’.Footnote 25 As young Liverpool supporters in the 1970s, both Dave Hewitson and Nicky Allt commented on the growing ‘crews’ and ‘mobs’ attending fixtures.Footnote 26 With this came the development of home and away ends – Everton's Gwladys Street and Liverpool's Kop assuming the mantle of the former, the Park End and Anfield Road End gaining a reputation as the latter. The violent rituals of territory observed by Robins and Cohen on the North Bank were likewise on display in Liverpool. During a fourth round FA Cup match between Everton and Millwall in February 1973, approximately 50 Millwall fans positioned themselves within the Gwladys Street. By kick-off, 11 had been seriously injured, with a screwdriver and a hatchet amongst the weapons confiscated.Footnote 27 Interviewed from his hospital bed the next day, one of the victims – 17 years old – framed the events within the intricate socio-spatial geography of the stadium: ‘there was no provocation. It was just because we were at their end of the ground.’Footnote 28 Andy Nicholls, who witnessed the scenes as a young Everton supporter, offered a similar explanation: ‘the Gwladys Street was the home end and was never taken. Only Millwall ever tried, and they paid dearly.’Footnote 29

If the transformation of the inner city was enabling fundamental changes to the cultures of football spectatorship, then those changes were occurring within an urban space that, as highlighted by John Bale, had been broadly static for much of the preceding half-century.Footnote 30 Whereas clubs had previously enacted piecemeal changes at the request of local police forces – curved arches behind Goodison's goals in 1964 for the protection of goalkeepers, for example – stadiums across the country remained largely unregulated urban spaces that tolerated the fluid movement of people within them. The shifting nature of terrace spectatorship was therefore seen to combine with out-dated stadiums so that national concerns soon translated into political action, centred on Denis Howell during his spells as minister for sport between 1964 and 1979. A series of parliamentary enquiries, reports and working groups were commissioned by the Home Office and the Department of the Environment from the late 1960s onwards in an attempt to better understand the stadium and regulate the behaviour of disorderly spectators. For example, commissioned by Howell to undertake an experiment into crowd psychology in 1968, John Harrington recommended a variety of physical alterations to stadiums to allow for more invasive policing practices, including perimeter barriers, gangways and enclosed pens.Footnote 31 One year later, Howell established a working party on crowd behaviour under the stewardship of Sir John Lang, vice chairman of the Sports Council. The subsequent Lang Report recommended comprehensive improvements in the segregation, policing and surveillance of supporters, including the separation of stands by barriers and their subsequent division into pens. On occasions when trouble was expected, Lang urged local authorities to substantially increase policing presence while also contemplating the potential applications of closed-circuit television systems, a technology that had already been tentatively utilized by police forces in London and Liverpool as a means of policing problematic urban areas.Footnote 32 The 1972 Wheatley Report – commissioned in the aftermath of the 1971 Ibrox Park disaster, in which 66 spectators were killed in a crush while attempting to leave the stadium during a Glasgow Old Firm match – firmly recommended that stadiums be subject to a national licensing system.Footnote 33 The subsequent Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 adopted many of Harrington's, Lang's and Wheatley's recommendations, essentially mandating updates to terrace structures, crush barriers, fencing and pens, framing the concept of public order around the issue of the movement and confinement of supposedly problematic urban populations. The Act established a ‘Green Code’ that compelled stadiums to seek a safety certificate issued by the local authority and – while designation was ultimately reliant on the varying interpretations of local authorities – by 1982, 50 league grounds across the country had been officially designated.Footnote 34

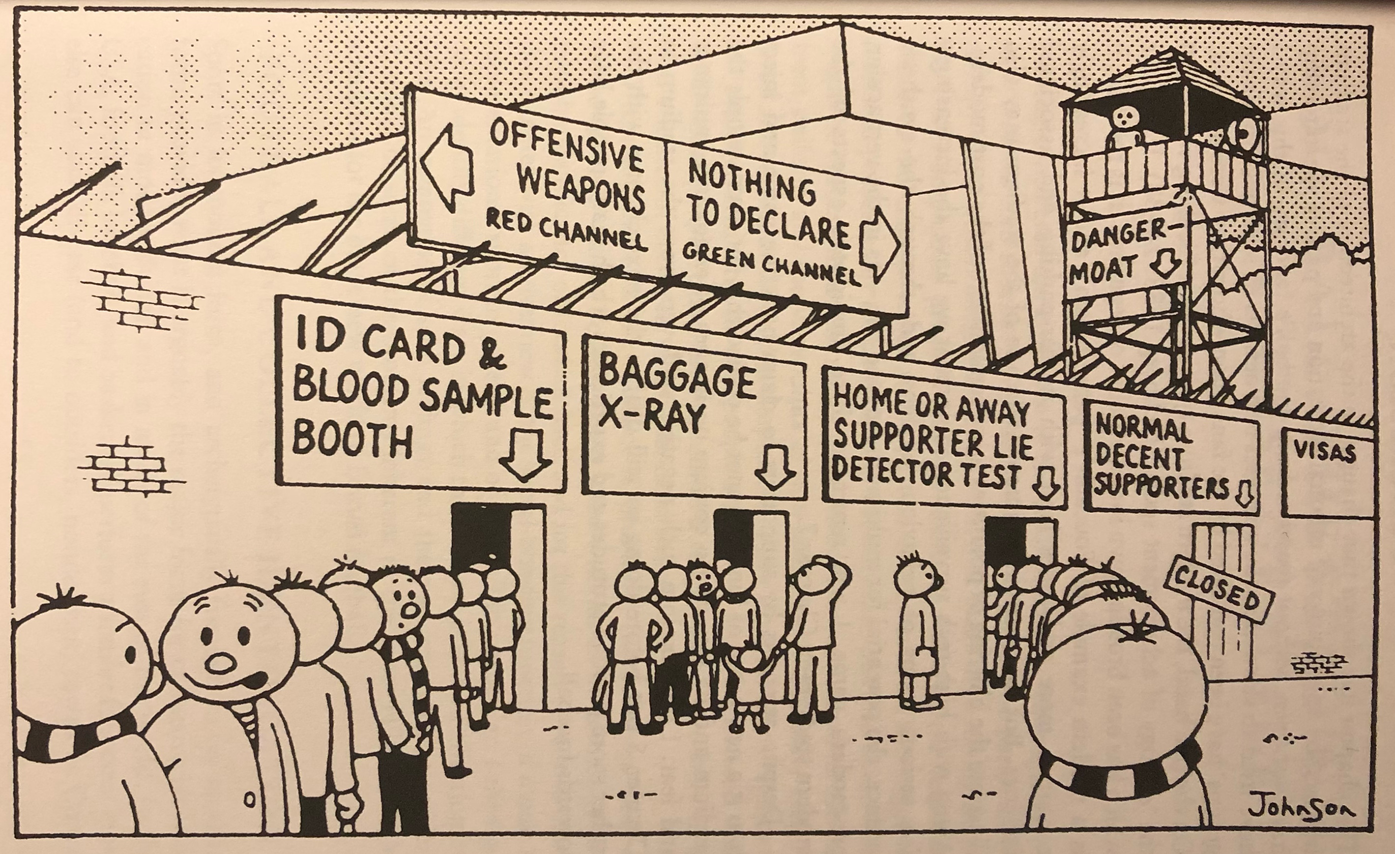

The similitude between the figure of the football delinquent and actual football supporters can be easily questioned. While national attendance figures undoubtedly dropped between the beginning of the 1960s and the mid-1980s, First Division crowds remained large, whereas figures for actual violence were low and disorder only ever engaged a small proportion of spectators – although several contemporary studies noted how official statistics perhaps better reflected diverse and poorly defined legal interpretations of public order offences as well as the contextual contingenices of policing.Footnote 35 Moreover, direct experience of disorder was largely dependent on positioning within the stadium, with seated grandstands serving up a more leisurely experience than the standing terrace. Regardless of this, concern for ‘football rowdyism’ took on all the hallmarks of a fully fledged moral panic and it is undoubtedly the case that the figure of the football delinquent made tangible material changes to the city. In a process that would reflect broader trends towards the micro-management of problematic inner-city spaces via doctrines that relied upon the assumption that poorly designed environments inherently fostered disorder – such as vandal-proofing, defensible space and ‘broken windows’ – the result of increased state interest in regulating the behaviour of football supporters was the promotion of a range of aggressive architectural policies that transformed stadiums from largely open and fluid arenas into disciplinary landscapes of surveillance and control.Footnote 36 Indeed, Brett Bebber has described the Act as the definitive articulation of a total policy of containment, addressing both popular fears about football disasters in unsafe, decrepit stadiums and the threat to enjoyment of football leisure by disruptive, violent fans.Footnote 37 By the mid-1970s, physical barriers and pens were commonplace, whereas technological developments in CCTV were improving the coverage and sophistication of surveillance.Footnote 38 With individuals inserted into enclosed and segmented places and with movements supervised and recorded, British stadiums bore increasing resemblance to Foucauldian panopticons, a comparison not lost on one American observer, who in 1980 noted that the ‘guards, barbed wire fences and escape tunnels which are deemed necessary…reminds those from the other side of the Atlantic of a security system more suitable to a prison’.Footnote 39 Indeed, the scene was only half-parodied in Figure 1, a cartoon published in national fanzine, When Saturday Comes, in the late 1980s illustrating the high degree of fortification within British stadiums.

Figure 1. Cartoon in popular fanzine, When Saturday Comes, illustrating the high degree of fortification within British stadiums by the late 1980s. Source: When Saturday Comes, 25 (1989), 10–11.

Liverpool's stadiums underwent a series of alterations in line with national trends. For example, in August 1972, The Observer reported that Liverpool Police had installed ‘steel shackles in the detention rooms at the city's two First Division football grounds to help them deal with soccer hooligans’, although in an attempt to ease concerns, a spokesman for the force commented that he ‘would prefer to call them restraining rings’.Footnote 40 With an upcoming home fixture against Manchester United causing concern for the city's police force in 1975, Liverpool took the decision to erect two five-feet-high walls of tubular steel up the entirety of the Anfield Road End, with a three-foot gap in between for police officers to patrol and remove disorderly spectators.Footnote 41 Ostensibly a temporary measure, the wall became a permanent fixture and was described by the Guardian as ‘Liverpool's own “Iron Curtain”’.Footnote 42 Two years later, perimeter fencing had been erected around the entirety of the stands to deter pitch invasions, with similar precautions taken at Goodison.Footnote 43 Finally, in 1985, Everton and Liverpool became the first British clubs to install colour CCTV cameras and immediate printing technology linked to monitors in the grounds’ control rooms. Merseyside Police boasted that improved systems allowed high-quality colour images to be handed to police ‘in seconds for immediate identification’ and arrest of troublemakers.Footnote 44

Spectator and community responses

The changes witnessed at Anfield and Goodison had a significant effect on how the stadiums were used by supporters and, by extension, local communities and the police. The material changes brought into law under the Safety of Sports Grounds Act with the intention of quelling public disorder within a problematic urban space instead had a series of dysfunctional and unintended consequences. Far from eliminating disorder amongst certain sections of spectators, those wishing to engage in hooliganism found continuing opportunity to do so both within the stadium's evolving architecture of surveillance and, crucially, in the surrounding streets onto which the crisis of the inner city was unfolding. This section will consider the actions of disorderly spectators, local communities and the police and how the activities of each party were inherently framed within the context of the decaying inner city.

By eliminating the tradition of swapping ends and cutting down on the opportunity for face-to-face confrontation, the material changes to Liverpool's stadiums undoubtedly ensured a greater degree of order and control over spectators. However, the introduction of fences, pens and barriers had the inadvertent effect of condensing disorder into specific sections of Anfield and Goodison, demarcating and legitimating territories with a greater clarity than spectators could have ever achieved on their own.Footnote 45 With home ends now practically unassailable, spectators seeking confrontation situated themselves as near as possible to visiting supporters, thereby shifting rather than eliminating the spaces of disorder. At Anfield, Hewitson commented that by the late 1970s ‘the Kop was losing its charm’ and a ‘nascent rival was emerging in the form of the Anfield Road End’, whereas at Goodison, Nicholls suggested that he was ‘always in the Park End if there was going to be trouble’.Footnote 46 Moreover, poor construction and variable levels of policing meant that barriers were frequently circumvented. In a 1971 derby fixture at Goodison, for example, police reported that Liverpool spectators used various tools to disassemble crush barriers.Footnote 47 In describing a fixture against Middlesbrough in 1978, Allt recalled how around 80 supporters climbed over Liverpool's ‘Iron Curtain’ into the away end, suggesting that ‘no matter what the police did, more and more kept making their way across the narrow divide’.Footnote 48 That face-to-face confrontation within the stadium remained possible was dramatically highlighted at Anfield in April 1985, as the Daily Post reported that three Manchester United fans had been hospitalized with knife wounds and a policeman injured following clashes inside the ground.Footnote 49 Ticketed checks and surveillance along entry gates were supposed to avoid scenes of this nature unfolding, though a feigned native accent would see away supporters pass through these obstacles easily enough.

The issue of compartmentalizing disorder was perhaps best exhibited by the boys’ pen, a development that more broadly reflected the ambiguous position of youth within inner-city settings and the key rhetorical role of the juvenile delinquent in understandings of the urban crisis. Bill Osgerby has observed that, by the 1970s, sections of working-class youngsters had become subject to much harsher measures of discipline and control, whereas John Davis has commented on how the hooligan was to be elevated to one of the major positions in the gallery of working-class deviant youth types as the decade wore on.Footnote 50 Indeed, the process of demonizing working-class youth was inherently emplaced and, in much the same way as Louise Jackson has suggested that coffee clubs became the site of rigorous attempts at a local level to define and regulate public space and to intensify surveillance on young people, so the boys’ pen became a crucial method of similarly controlling youth within a different urban setting.Footnote 51 Prompted by the very fears described by Osgerby and Davis, Lang had specifically endorsed ‘the segregation of unaccompanied schoolchildren’, a practice that had long been employed at Anfield and Goodison via the boys’ pens – situated within the Kop and in the corner of the Bullens Road and Gwladys Street stands.Footnote 52 The pen's intentions were ambiguous – appearing to exist both as a means of protecting youth from the harsher vagaries of the adult crowd and as a way of minimizing their own potentially deviant effects – although the effect of concentrating youths into a smaller space largely free from adult supervision was clear. Far from providing sanctuary, the pen was recalled as rowdy and violent. Upon the closure of Anfield's pen in 1978, the Liverpool Echo claimed that it had ‘virtually guaranteed safety due to the presence of two police officers in a segregated expanse of terracing’.Footnote 53 Safety from what, and whom, was never established and personal accounts paint a contradictory picture. Brian Burrows, attending his first matches at Goodison in the mid-1960s, recalled how ‘I foolishly used to go into the boys’ pen. It was nuts. It had all the scallies of Liverpool in there with knives, blackmailing and taking money off you.’Footnote 54 Likewise, Eddie, a young Liverpool fan during the mid-1970s recalled how ‘you only went into the boys’ pen if you could survive it. And to do that, you had to be cute, tough or as wide as the hills.’Footnote 55 Indeed, escaping the boys’ pen became a rite of passage, as Allt recalled how ‘kick off was followed by a mass bunk-out…a quick up and over the steel fence, followed by a graceful dive into the swaying arms of the Kop’.Footnote 56

That the material changes recommended by Lang and others were ineffective or easily eluded was reflected in the continuing problem of projectiles. A national Sports Council report from 1978 found that ‘where physical contact is inhibited, the next best thing is contact via missile throwing’.Footnote 57 By the late 1970s, prominent messages had been installed across both stadiums – including on Everton's Main Stand, as seen in Figure 2 – asking fans to refrain from throwing missiles. The message was, at best, only partially effective. Nicholls, for example, recalled coins, darts, golf and snooker balls occasionally ‘raining from end to end’.Footnote 58 At Anfield, the ‘Anny Road Darts Team’ was of particular notoriety, the impact of which can be witnessed in Figure 3.Footnote 59 Hosted at Goodison Park, the 1985 FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Manchester United witnessed both sets of supporters throw an assortment of objects over the barriers. Two days later, a shocked Merseyside Police displayed a diverse arsenal of weapons, ranging from keys and batteries to a lump of glass, a marble egg and, most troublingly, a nail-studded golf ball.Footnote 60

Figure 2. Everton's Bob Latchford beats Chelsea goalkeeper Peter Bonetti to score, with prominent anti-projectile messaging in the background, 1978. Source: Harry Ormesher/Popperfoto.

Figure 3. A Tottenham supporter is led way from the Anfield Road End after having a dart thrown at him by Liverpool fans, 1980. Source: PA Images/Alamy.

Disorder therefore continued to function within the stadium, evolving in response to the measures designed to erase it. However, as face-to-face confrontation became more difficult, those seeking to engage in disorder shifted their view towards the surrounding inner city, a trend picked up in Scottish football in 1977 by the Working Group on Football Behaviour. The report stressed that ‘the recipients of the worst anti-social aspects of this behaviour are in many instances innocent members of the public and their property in the immediate vicinity of the ground’.Footnote 61 In a similar fashion, a 1984 Department of the Environment report commented on how segregational measures at football grounds ‘may have led to trouble being “squeezed out” to other places – the streets’ in particular.Footnote 62 Colin Ward's introductory account of attempting to escape Anfield is particularly poignant in this regard. Pushed beyond the confines of the stadium, those seeking disorder actively appropriated surrounding streets as theatres for violent confrontations. In short, legislation focused on tackling disorder within the stadium had the unintended consequence of exporting it outwards and into inner-city communities where it was generally more difficult to control. By the time the Working Group published its conclusions, both Liverpool and Everton had largely completed the installation of security measures within the city's stadiums. It is therefore telling that the Anfield Tenants’ Association called a meeting in response to an upsurge in trouble after recent matches in March 1977.Footnote 63 The 1976/77 and 1977/78 seasons were witness to unprecedented trouble in the streets surrounding the grounds, and Anfield in particular. Street skirmishes between rival fans were, of course, nothing new. In 1970, for example, Superintendent Carroll of the Liverpool and Bootle Constabulary suggested that the city's most common public order issue was that of ‘football hooligans attacking supporters of the visiting teams’ and ‘rampaging through the streets after the game’.Footnote 64 By the late 1970s, however, the scale and increasing regularity of street disorder was a significant source of fear and annoyance for local communities and the police. Crucially, Liverpool's unfolding urban crisis gifted disorderly spectators a landscape highly amenable to their intentions.

A variety of first-hand testimonies attest to the emplaced nature of public disorder as hooligans appropriated the characteristics of the decaying inner city to create a series of topophobias. For away supporters, the city's stadiums represented the finishing line in a treacherous three-mile journey from Lime Street Station, a route that took in a significant section of the inner city that was, by the mid-1970s, an epitome of urban decay; a muddled landscape of alleyways, tenements, high rises and derelict land mixed with remaining terraced communities. Parts of the city became notorious for trouble. For example, in 1971, one community newspaper described the area between Everton Valley and Mile End as a ‘hooligan's hunting ground’.Footnote 65 The area's visual characteristics contributed towards a sense of fear among visiting supporters, with Scotland Road particularly dreaded. Once the thriving hub of a working-class community, it was left eviscerated by high-rise renewal projects and the approach road for the Wallasey Tunnel. Nicholls described the area as ‘a feared stretch that typified inner-city decay. You could be mugged on “Scotty” on a Tuesday morning in June, never mind a Saturday in November when thugs…were on the lookout for a stray Cockney or Manc.’Footnote 66 Similarly, Eddie recalled that ‘it looked evil, you weren't walking around Chelsea Flower Garden. You could tell just by the surroundings this was going to be dodgy – put yourself in the shoes of an away supporter and it must have been scary.’Footnote 67 Seemingly designed for concealment, those seeking disorder utilized their knowledge of a landscape that provided ample opportunity for ambush. For example, Allt reimagined the flats and tenements along Scotland Road as points of opportunity:

Gerard and Fontenoy Gardens, along with the myriad of streets that ran off Scotland Road and Great Homer Street were the main ambush points. The tenement landings and back jiggers would be full of marauding skinheads and bootboys…and were a concrete maze if you didn't know the layout. The bizzies had an impossible task of clearing out the gangs on a match day.Footnote 68

Able to appear and disappear like fleeting shadows, many were encouraged to engage in disorderly activities, so much so that a reputation for ambush became the area's distinguishing feature.Footnote 69 A Middlesbrough supporter hauled in front of Liverpool City Magistrates and fined £300 for possessing a knife in 1977, when asked to explain why it was on his person, simply replied, ‘I had it to protect myself. I've been to Liverpool before.’Footnote 70 Tellingly, a 1987 report from the University of Leicester suggested that Liverpool's hooligan groups were best known ‘less for their organisation or general fighting prowess than they were for their alleged dangerousness when faced in Liverpool’.Footnote 71

Although hooliganism attracted relatively small numbers – what Merseyside Police would deem an ‘irresponsible lunatic minority’ – their activities caused considerable distress for local communities, periodically transforming inner-city areas into warzones.Footnote 72 After Liverpool had entertained Newcastle in March 1977, the Daily Post reported how several streets around Anfield had witnessed large numbers hurling bricks, breaking windows and damaging cars. Likening the scene two hours before kick-off to a ‘living hell’, Bob Hardcastle, a resident of Wylva Road, suggested that ‘there must have been over 2,000 altogether and they just picked up anything they could find as they marched towards each other. It was like a battleground and everyone in the area was terrified.’ Hardcastle went on to imply that it was the decaying nature of Liverpool's inner city that provided the opportunity and the resources needed to conduct street mêlées. At the bottom of Wylva Road was an empty and derelict plot of land where a church had once stood, strewn with bricks and debris. ‘Someone ought to clear that’, Hardcastle said, ‘it's like a red rag to bull.’Footnote 73 Two weeks later, the Anfield Tenants’ Association was forced to present a petition to the city council after a particularly troublesome cup weekend in which Everton and Liverpool had both been playing at home and close to 100,000 spectators descended upon the area. The next day, the Echo reported on countless windows that had been broken and one youth stabbed as fans left each stadium.Footnote 74 Urged on by the Tenants’ Association, county councillor for Anfield, Frank McGurk, pleaded with local authorities to get a grip on the situation, whilst his city council counterpart, Myra Fitzsimmons, called for a conference of the city's top public figures to discuss potential solutions to disorder in the build-up and aftermath of fixtures.Footnote 75

When Colin Ward arrived in Liverpool a year later, the community's patience had reached breaking point. The Daily Post described the clashes after the Arsenal fixture as ‘the worst scenes witnessed by police and local residents for many years’ and the sense of fear and frustration amongst the local community was tangible.Footnote 76 Mr Carp of long-suffering Wylva Road recalled the view from his front window as one of ‘dozens of youths taking turns to kick at somebody’, whereas Carp's neighbour, Mrs Kelly, described how her grandchildren had to be ‘evacuated from the house like refugees in the middle of a war’.Footnote 77 The publican of the Albert and Park Hotel in nearby Walton Breck Road, which found its windows the target of both home and away supporters, even likened it to his experiences in the military: ‘I was in the army in Northern Ireland in 1972 – tonight was so bad that I can compare the two situations.’Footnote 78 While these incidents were far from a weekly occurrence, disturbances of this scale – simmering to the surface as the match approached before boiling over in the ensuing hours – would last long in the community's memory and their unpredictable nature and looming threat of reoccurrence caused considerable unease. In response, the indignation of local residents and their desire to restore control over their streets was often expressed through a variety of small, everyday acts that aimed to expand techniques of surveillance and segregation beyond the confines of the stadium and directly into inner-city streets. The Daily Post reported how residents near Anfield ‘stand at their gates to make sure no damage is done to property when the match is on’, whereas local businesses ‘barricade themselves in for protection’.Footnote 79 After the unsavoury scenes of the Arsenal fixture, the Anfield Residents Committee threatened to ‘launch a “people's war” to protect themselves and their homes’ and even discussed blocking roads with cars to create ‘manned barricades’.Footnote 80 Councillor Fitzsimmons recognized the need to filter out potentially disorderly crowds from local communities and suggested exploring the possibility of channelling supporters to avoid residential streets.Footnote 81

Fitzsimmons’ appeal was already on the minds of authorities, both nationally and locally.Footnote 82 Sophisticated and coercive techniques of public order policing, which burst into the nation's consciousness alongside the petrol bombs and pitched battles of the 1981 disturbances, were partially practised on football supporters in problematic sections of Liverpool's inner city from the mid-1970s onwards. Indeed, as a method of stymying disorder, Merseyside Police wholeheartedly embraced the segregation of visiting supporters in their movement through the inner city. By 1979, the provision of escorts to and from the ground involved what the force described as ‘a considerable commitment’.Footnote 83 Eddie remembered the route well: ‘Scotland Road was where the police used to take them. They'd never bring them into the housing estates. Didn't wanna go up Netherfield Road in case windows got smashed. So they'd take them to the main roads and keep them there.’Footnote 84 Likewise, in his 1980 profile of Merseyside Police's A-Division, James McClure witnessed similar practices:

The station exit suddenly fills with the vanguard of 2000 supporters, looking as any new arrivals in a strange city usually look like, slightly dazed and unsure of themselves.

‘Turn to yer right, lads.’ Says the first Liverpool policeman they set eyes on. ‘You've got a long way to go, y'know, so don't waste yer –’

‘How far is it then?’

‘Two mile – but don't let that bother yer.’ He grins and adds, ‘Lambs to the slaughter!’

That gets a big laugh…Lambs they may not be, but they seem willing, even gratefully eager, to be shepherded along Lime Street in a wide column…The sergeant's van moves ahead of the marchers to check the route once again for any pockets of ambushers that may be lurking.Footnote 85

By the mid-1980s, it was not uncommon for Merseyside Police to stop incoming trains at Edge Hill Station and shuttle supporters onto stadium-bound buses, or to hold away supporters within the ground after the match, thus completely removing the risk of potential clashes between large groups within the urban environment. That the city's specialized public order departments – the Task Force, established in 1969, and their replacements, the Operational Support Division from 1976 – often assisted these assignments was indicative of broader changes to inner-city policing during this period, reflecting the shift away from consensual policing towards more intrusive approaches that utilized technologies such as wireless communications, electronic surveillance and centralized operational support that adopted the logic of swamping problematic urban spaces at certain times. Indeed, by 1979, the Guardian suggested that Merseyside Police had ‘chosen to react to its environment by adopting an aggressive, high profile presence, patrolling incessantly and reacting quickly and in strength’.Footnote 86 By the mid-1980s, one study suggested that it was ‘rare to see identifiable visiting fans walking around or near the Merseyside grounds without police cover’ and championed the success of police segregation in noting that local supporters ‘barely come across visiting fans face-to-face during the entire season as the approaches to the home terraces…are well clear of the normal routes used to ferry visitors to and from games’.Footnote 87

With the odds of either side stumbling across each other in a chance encounter becoming increasingly improbable, hooligans began to self-segregate as a means of continuing disorderly activities. Although undoubtedly contentious, former hooligans’ assertions that they only sought to engage with those who were willing appears to hold some truth as, policed to the margins, they sought out liminal urban spaces to host skirmishes where surveillance would be negligible and policing difficult – such as Stanley Park, 110 acres of green space situated between the city's stadiums.Footnote 88 Entry into these spaces relied on a pre-existing knowledge of the local landscape and those who did either wittingly or unwittingly signalled their desire to fight. Crucially, these spaces were a point of negotiation for many ‘ordinary’ supporters as well. Whereas the declining attendances of the 1970s and 1980s cannot be attributed to hooliganism alone – increasing unemployment, rising ticket prices, more varied forms of leisure and inner-city depopulation all played their part – the topophobias created by hooligans undoubtedly influenced individual decisions to enter the inner city on a Saturday. In stating that ‘I wont let my son go to the matches because of the violence’, one mother quoted in a 1977 Daily Post op-ed on hooliganism appeared to summarize the concerns of many.Footnote 89 However, outright avoidance of the landscapes moulded by football was not the most common decision, something to which relatively stable local attendance figures during this period attest. More often than not, the negotiation was nuanced and relied upon supporters’ pre-existing knowledge of the city's disorderly spaces, established through hearsay or experience. Dave, for example, commented on how easily confrontation could be sidestepped. Just as hooligans utilized their understandings of inner-city neighbourhoods to evade surveillance and engage in disorder, ordinary supporters deployed their own knowledge precisely to avoid such trouble:

Stanley Park was where all the shit happened. We'd circumvent that and go down Walton Lane. So you'd hear it, and you'd see it, but it was easy to avoid. It was concentrated in certain areas. The troublemakers wouldn't go looking for anyone else. It was almost like you were invisible. I'm sure there were exceptions, but if you went round it, it was almost as if it didn't happen.Footnote 90

Conclusion

Tracing the connections between specific urban spaces such as stadiums and their relationship to wider discursive constructs and particular lived experiences is important to the study of the post-war city, especially given that the social and cultural characteristics of the stadium as an urban space are often overlooked. The connections between the stadium and the city raise intriguing questions about the perceptions and reactions to and experiences of urban decline during the 1970s and 1980s. As a physical location through which many of the period's emerging urban anxieties manifested, the profound changes taking place within British stadiums were driven by the ostensibly worsening behavioural standards of the ‘naturally tough’ urban supporters who frequented the terrace. Those changes – be that the erection of fencing, the installation of CCTV or the more sophisticated techniques of policing – epitomized broader trends towards the micro-management of problematic urban spaces through architectural doctrines like ‘defensible space’ or ‘vandal-proofing’, or to the development of public order policing techniques and specialist police divisions. In short, the idea of an inner-city crisis grew up around material spaces like the football stadium and the emplacement of discursive constructs such as the hooligan within them. Perhaps most importantly, this process points to the complex relationship between the state, the city and its citizens, and how attempts to exert authority and control over the urban working class in this period were met with myriad responses that demonstrate the capacity of urban populations to resist and modify the schemes that attempted to mould their behaviour.

Dave's allusion to the fact that the match-day inner city was viewed and perceived in vastly different ways by all parties is a useful point upon which to conclude. Liverpool's urban renewal programmes were partly responsible for worsening standards of spectator behaviour from the early 1960s, with the resulting disorder subsequently used to portray the city's stadiums as some of the most acute points of its urban decline and central to its supposed social and moral collapse. However, for many football supporters arriving within the vicinity of stadiums on a Saturday afternoon, the inner city was not a singular landscape but a series of concurrent ones; a continuum between order and disorder, normality and absurdity, inclusion and exclusion. The football stadium, and the routines and rituals that surrounded it, legitimated certain forms of behaviour and established concurrent landscapes of fandom and disorder; the former steeped in affective and carnivalesque notions of place, the latter transforming everyday urban spaces into battlegrounds defined by fear and violence. In short, the unease and anxiety generated by football fixtures made drastic changes to the governance, materiality and, crucially, the use of a variety of inner-city spaces in this period. Stadiums were not merely the location for the passive consumption of spectacle or governmental and architectural intervention but were instead sites of collective urban experience, with supporters and stadiums locked in a mutually constitutive relationship by which spectators shaped the social and material geography of the stadium, just as the materiality of the stadium shaped them in turn.