Around the middle of the third century BC, the diphthong /ɛi/ underwent monophthongisation to close mid /eː/; about a century later, this /eː/ was raised further to /iː/, thus falling together with inherited /iː/ (see p. 40). We will see that neither <ei> nor <e> for /iː/ – and for /i/ which results from shortening of /iː/ – are very well attested in the corpora. Nonetheless, even after the first century BC/Augustan period a few plausible examples of each do pop up, in the case of <ei> in one of the Claudius Tiberianus letters, which in general often seem to preserve old-fashioned spelling, and, in the case of <e>, at Vindolanda.

<ei> for /iː/

The effect that this monophthongisation had on spelling was a subject of considerable discussion in the second and first century BC and beyond. The advantage of <ei> was that it provided a spelling that allowed /iː/ and /i/ to be distinguished, but Roman writers disagreed on the exact contexts in which <ei> should be used, with Lucilius, Accius and Varro all apparently taking differing positions (Reference SomervilleSomerville 2007; Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 53–8; Reference Chahoud, Pezzini and TaylorChahoud 2019: 50–3, 57–9, 67–9).

The use of <ei> for /iː/ was still extant in literary contexts towards the end of the first century BC and perhaps later. The Gallus papyrus (Reference Anderson, Parsons and NisbetAnderson et al. 1979), probably from c. 50–20 BC, with the reign of Augustus particularly likely, contains the spellings spolieis for spoliīs, deiuitiora for dīuitiōra, tueis for tuīs and deicere for dīcere, all with <ei> for *ei̯ beside mihi (whose final syllable scans heavy) and tibi (with light final syllable) < *-ei̯;Footnote 1 <ei> for /iː/ is attested in manuscripts of authors as late as Aulus Gellius (13.4.1, writing in the second century AD), along with corruptions which suggest scribes dealing with the unfamiliar spelling (Reference Gibson and ClacksonGibson 2011: 53–4). According to Reference NikitinaNikitina (2015: 58–70), legal texts and ‘official’ inscriptions of the first century BC show a tendency to prefer <ei> for /iː/, especially from original /ɛi/, whereas from the Augustan period there is a clear move to using the <i> spelling, with very occasional instances of <ei>.

The Roman writers on language send mixed messages about the status of <ei>. In the late first century AD, Quintilian says:

diutius durauit, ut e et i iungendis eadem ratione, qua Graeci, ei uterentur: ea casibus numerisque discreta est, ut Lucilius praecipit … quod quidem cum superuacuum est, quia i tam longae quam breuis naturam habet, tum incommodum aliquando; nam in iis, quae proximam ab ultima litteram e habebunt et i longa terminabuntur, illam rationem sequentes utemur e gemina, qualia sunt haec “aurei” “argentei” et his similia.

The habit of joining e and i together lasted rather longer, on the same reasoning as the Greeks used ei: and this usage is decided by case and number, as Lucilius teaches … This is entirely superfluous, because i has the same quality, whether long or short, and sometimes it is actively inconvenient; because in words which end in an e followed by long ī (like aureī and argenteī) we would have to write two es, if we followed this rule [i.e. aureei, argenteei].

It is not clear from this passage whether or not there are contemporaries of Quintilian who still use <ei>; although he only mentions Lucilius, the fact that Quintilian feels the need to argue against it may suggest that in fact there are. The same is true of Velius Longus’ discussion:

hic quaeritur etiam an per ‘e’ et ‘i’ quaedam debeant scribi secundum consuetudinem graecam. nonnulli enim ea quae producerentur sic scripserunt, alii contenti fuerunt huic productioni ‘i’ longam aut notam dedisse. alii uero, quorum est item Lucilius, uarie scriptitauerunt, siquidem in iis quae producerentur alia per ‘i’ longam, alia per ‘e’ et ‘i’ notauerunt … hoc mihi uidetur superuacaneae obseruationis.

Now I turn to the question whether certain words should be written with ei as in Greek. For some have written long instances of i in this way, while others have been content to use an i-longa for this long vowel or to have given it a mark. Still others, among whom is Lucilius, have written it in various ways, since they have written long i sometimes with i-longa and sometimes with ei … This seems to me to be unnecessary pedantry.

However, Charisius (Reference BarwickBarwick 1964: 164.21–29) attributes to Pliny (the Elder) a rule for explaining when third declension accusative plurals are in -eis, suggesting that at least some writers in the first century AD used <ei>, at least in this context, and in the late second or early third century AD, Terentianus Maurus also implies that <ei> is still in use, at least in particular lexemes and endings:

sic erit nobis et ista rarior dipthongos ‘ei’, ‘e’ uidemus quando fixam principali in nomine: ‘eitur in siluam’ necesse est ‘e’ et ‘i’ conectere, principali namque uerbo nascitur, quod est ‘eo’. sic ‘oueis’ plures et ‘omneis’ scribimus pluraliter: non enim nunc addis ‘e’, sed permanet sicut fuit lector et non singularem nominatiuum sciet, uel sequentem, qui prioris saepe similis editur.

For us that diphthong <ei> is rarer, when we see <e> fixed in the original word: in ‘eitur in siluam’ it is necessary to join <e> and <i>, because <e> occurs in the base word, which is ‘eo’. In the same way, we often write ‘oueis’ and ‘omneis’ in the [accusative] plural: here we are not adding an <e>, rather it is retained from the nominative plural so that the reader knows it is not the nominative singular or the case which follows it [i.e. the genitive], which is often identical.

Marius Victorinus (Ars grammatica 4.4 = GL 6.8.13–14) attributes the <ei> spelling to the antiqui, and at 4.59 (GL 6.17.21–18.10) notes that the priores used it to represent the nominative plural of second declension nouns as opposed to the genitive singular. He follows this with the observation that the use of <ei> is a topic which has exercised all writers on orthography, although without making it clear whether any modern writers use it (he himself appears to be opposed).

Diomedes, however, in the late fourth century, is much more explicit that he considers this spelling out of use:

ex his diphthongis ei, cum apud ueteres frequentaretur, usu posteritatis explosa est.

Of these diphthongs, ei, while it was used frequently by the ancients, has been rejected in subsequent usage.

Any kind of conclusive, or even representative, survey of the use of <ei> in the inscriptional context is made extremely difficult by the problems involved in searching on the online databases. The string ‘ei’ in standard spelling represents several sequences of phonemes, while ‘i’ represents (at least) /j/, /i/ and /iː/, all highly frequent phonemes. It is thus extremely difficult to get results which are restricted to the use of <ei> which is desired, and completely impossible to compare it with instances of <i> for /iː/ (and even more impossible, so to speak, to isolate cases of /iː/ < /ɛi/). I carried out a search for the sequence ‘{e}i’ on a plaintext copy of all the inscriptions in the EDCS downloaded on 18/06/2019. After removing cases of <ei> which did not represent /iː/ or /i/, I identified a maximum of 15 dated to the first four centuries AD.Footnote 2 However, this is highly likely to undercount the total instances, partly because of the usual problems with this database, partly because of my own decisions of what to include.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, this does not suggest that <ei> was in common usage in this period (as of 06/04/2021, the database finds 150,594 inscriptions dated from the first to fourth century AD).

In general, the corpora agree with this picture, since <ei> for /iː/ is entirely absent from the Vindonissa, Vindolanda and London tablets, the TPSulp. and TH2 tablets, the Bu Njem ostraca, the Dura Europos papyri, and the graffiti from the Paedagogium.Footnote 4 There are a couple of examples where <ei> is used for the sequence /i.iː/: one in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets ([ma]ncipeis, CIL 4.3340.74, for mancipiīs), in the scribal portion of a tablet which is undated but presumably belongs to the 50s or 60s AD; and one in the Isola Sacra inscriptions (macereis, IS 1, for māceriīs).

There are two possibilities to explain these spellings. The first is that the sequence /i.iː/ has contracted to give /iː/ (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 110). In this scenario, <ei> is being used to represent the remaining /iː/. The second possibility is that the speaker has undergone raising of /ɛ/ to /i/ before another vowel in words like aureus ‘golden’ > /aurius/ (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 102–4). If this were the case, <ei> could be a hypercorrect spelling for /i.iː/. An example of such hypercorrection can be found in Terenteae for Terentiae in another Isola Sacra inscription (IS 27). There is no way to distinguish between these possibilities: neither inscription shows any other old-fashioned or substandard features (and nor do any of the other inscriptions from the same tomb, in the case of IS 1).

Otherwise, only the curse tablets and letters provide a certain amount of evidence for the continuing use of <ei> either to represent /iː/, [ĩː],Footnote 5 or etymological /iː/ which became /i/ by iambic shortening (on which, see p. 42), in words like ubi ‘when’ < ubī < ubei.Footnote 6

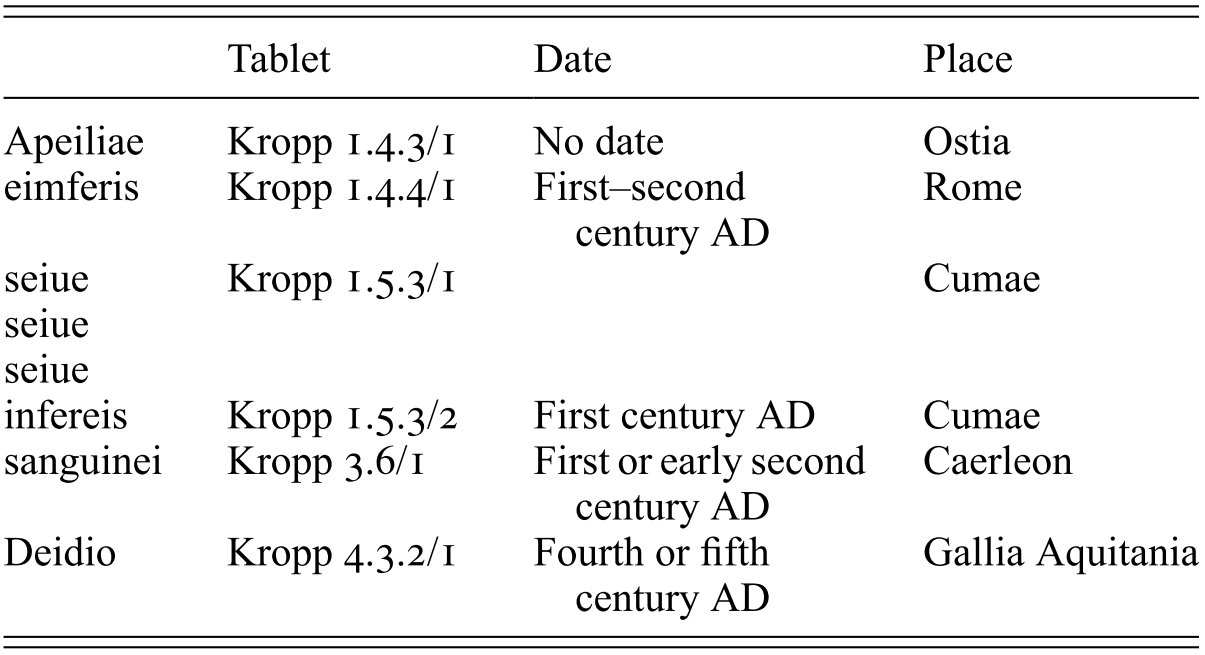

In the curse tablets <ei> is found, on the whole, in fairly early texts: in Kropp 10.1.1, from the later second century BC, and 1.4.4/3, 1.4.4/8, 1.4.4/9, 1.4.4/10, 1.4.4/11, 1.4.4/12, 2.1.1/1, 2.2.3/1, all from the first century BC, <ei> is used frequently (but not necessarily consistently), including for iambically shortened /i/ in tibei (1.4.4/3). There are a handful of other examples, although some are in undated tablets (see Table 1).Footnote 7 1.4.4/1, dated to the first two centuries AD, has the spelling suom twice, and otherwise is entirely standard (including nisi, whose final vowel would have been /iː/ prior to iambic shortening). 1.5.3/2 has largely standard spelling, though it is possible that the writer had the /eː/ and /i/ merger, given the spellings Caled[um, Cale[dum] for Calidum and niq[uis] for nēquis and possible ni[ue for nēue if correctly restored. However, the author could also be using the variant nī for nē in the latter two. In 3.6/1, sanguinei reflects the (originally i-stem) ablative *-īd; <i> is used for the iambically shortened final vowel of tibi and for /iː/ in ni ‘if not’. Substandard spellings are found in domna for domina and hyper-correct palleum for pallium. In the case of the very late Deidio (4.3.2/1), the use of <ei> may have been preserved in the family name: <i> is used for /iː/ in oculique. The writer shows substand-ard spelling in bolauerunt for uolāuē̆runt and pedis for pedēs.

Table 1 <ei> in the curse tablets, undated and first to fourth (or fifth) century AD

| Tablet | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apeiliae | Kropp 1.4.3/1 | No date | Ostia |

| eimferis | Kropp 1.4.4/1 | First–second century AD | Rome |

| Kropp 1.5.3/1 | Cumae | |

| infereis | Kropp 1.5.3/2 | First century AD | Cumae |

| sanguinei | Kropp 3.6/1 | First or early second century AD | Caerleon |

| Deidio | Kropp 4.3.2/1 | Fourth or fifth century AD | Gallia Aquitania |

Likewise, in the letters most examples of <ei> are found in texts dated to the first century BC or the Augustan period. In the case of CEL 3, from the second half of the first century BC, the writer seems not to have learnt the rule of when to use <ei> well, deploying it for short /i/ in sateis for satis and defendateis for dēfendātis alongside /iː/ in s]ẹi for sī and conserueis (twice) for conseruīs. If the author Phileros is also the writer he may not have been a native speaker of Latin. CEL 12, dated to 18 BC, has <ei> in eidus for īdūs. CEL 10, from the Augustan period, includes <ei> for iambically shortened /i/ in tibei beside <i> in mihi, and, mistakenly, in the second person singular future perfect uocāreis for uocaris by confusion with the perfect subjunctive uocārīs. Alongside these, the genuine cases of /iː/ (originally < /ɛi/) in quī and sī are spelt with <i>. This letter is characterised by both conservative spelling features alongside substandard orthography (on which, see pp. 10–11). CEL 13, from the early first century AD, includes tibei (beside tibi); other instances of etymological /ɛi/ are spelt with <i>in ịḷḷịṣ and ṣc̣ṛịp̣si.

Probably the latest example of <ei> in the corpora is reṣc̣ṛeibae (P. Mich. VIII 469.11/CEL 144) for rescrībe in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, in which most other instances of /iː/ are spelt <i>, including original /ɛi/ in uidit, [a]ttuli, tibi (with iambic shortening). This letter also includes three instances of the dative singular of illa written illei, as well as ille[i]. This could represent Classical illī but scholars have instead suggested that it be understood as an innovative feminine dative /illɛːiː/ which lies behind Romance forms such as Italian lei ‘she’ (Cugusi, in the commentary in CEL; Reference AdamsAdams 1977: 45–7; Reference Adams2013: 459–64).Footnote 8 Adams makes the point that in the other letters of the Claudius Tiberianus archive the masculine dative is always spelt illi, and that illei in this letter is therefore more likely to be a specifically feminine form. This is not a strong argument, however, since none of the other Tiberianus letters is written by the same hand. None of the other scribes uses <ei> at all, while that of 469/144 also uses it in reṣc̣ṛeibae. So the fact that in the other letters the masculine dative is illi tells us nothing about the spelling illei in 469/144.

Similar forms appear in the letters of Rustius Barbarus from the first century AD: a feminine dative illei (CEL 75), and a genitive illeius (CEL 77), the gender of whose referent cannot be determined. Nowhere else in these ostraca written by the same hand is there any example of /iː/ being spelt with <ei> (and there are very many examples of /iː/); this includes one instance of illi (in the same letter 77, probably masculine). Now, it is conceivable that this has something to do with the unique genitive and dative endings of pronouns: perhaps <ei> was preserved as a spelling in the educational tradition to mark out these curious endings; this would be particularly relevant in the genitive where original illīus underwent shortening to illius. The spelling with <ei> could then preserve a memory of the original length. However, in this case, given the existence of other evidence for similar feminine genitive and dative forms in Latin put forward by Adams, and the absence of other instances of <ei> for /iː/ in Rustius Barbarus, there is a strong possibility that illei and illeius represent special feminine forms rather than illī and illīus. Since these forms are therefore present in a corpus of similarly early date, it cannot be ruled out that illei in the Claudius Tiberianus letter is also a form of this type, rather than having <ei> for /iː/.

<e> for /iː/

In addition to the continuing use of <ei> for /iː/, <e> too apparently remained an infrequent possibility to represent /iː/. Quintilian provides the relevant examples leber for līber and Dioue Victore for Iouī Victorī in his list of old spellings at Institutio oratoria 1.4.17, implying that they are no longer in use, and I have not found any other reference in the writers on language. There are significant difficulties in finding examples of <e> for /iː/ in the epigraphic record as a whole; I have found 114 instances on LLDB in the first four centuries AD.Footnote 9 This number is almost certainly too high since some cases will be things like a mistaken use of the ablative -e in place of dative -ī, and many examples are for original /iː/, not from /ɛi/: these may be hypercorrect of course, but may also suggest that a different explanation should be sought. Nonetheless, these results imply that the <e> spelling did survive to some extent, although the spellings with <e> must represent a tiny proportion of all instances of <i> for /iː/.

Unsurprisingly, then, in the corpora there are only a very small number of examples of <e> for /iː/, of which a couple are very plausible. One is deuom (CEL 10) for dīuom ‘of gods’ in Suneros’ letter from the Augustan period characterised by conservative as well as substandard spelling (see pp. 10–11). Another is amẹcos (Tab. Vindol. 650) for amīcōs ‘friends’ in a letter at Vindolanda authored by one Ascanius who was apparently a comes Augusti, and hence of relatively high rank. The text is all in a single hand, but we cannot tell if it was that of Ascanius himself or a scribe. The letter was sent to Vindolanda and therefore does not necessarily reflect the same scribal tradition. The spelling is all otherwise standard, as far as we can tell. Reference AdamsAdams suggests (2003: 535) that the maintenance of pronunciation of /eː/ < /ɛi/ ‘was seen as a regionalism and belonged down the social scale’, but this does not fit well with the social context of the Vindolanda letter (although of course it could be a feature of the scribe’s Latin rather than Ascanius’).Footnote 10 However, Festus (Paul. Fest. 14.13) notes amecus as an old spelling,Footnote 11 so it may be better to see the spelling as old-fashioned.

In the curse tablets, a first century BC instance of <e> for /iː/ may be nesu (Kropp 1.4.2/2), if this stands for nīsum ‘pressure, act of straining’, although this text has a number of errors of writing (see p. 132 fn. 2).Footnote 12 Otherwise we find only 4 instances of <e>, all from Britain: deuo for dīuō (Kropp 3.15/1, 3.19/3) ‘god’, demediam (3.15/1) for dīmidiam ‘half’, and requeratat (3.7/1) for requīrat ‘may he seek’. Reference AdamsAdams (2007: 602) suggests that deuo could reflect a British pronunciation of deo ‘god’, or be a code-switch into British Celtic, for which dēuos would have been the word for ‘god’;Footnote 13 at any rate, it is not a good example of <e> for old-fashioned /iː/. We could have a hypercorrect old-fashioned spelling with <e> for /iː/ < *ī in demediam, but perhaps instead one should think of confusion between the prepositions dī- and dē-. Nor is requeratat a plausible example, since the writer of the text has made a large number of mistakes in the writing of the text (as distinct from substandard spellings), such as memina for fēmina, capolare for capitulāre, pulla for puella, uulleris for uolueris, llu for illum, Neptus for Neptūnus etc.

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, C. Novius Eunus writes dede (TPSulp. 51.2.13) for dedī‘I gave’. This could well be an old-fashioned spelling, since Eunus uses other old-fashioned spellings (see pp. 187, 202–4, and 262).Footnote 14 But we could also imagine repetition of the first syllable by accident (and Eunus is prone to mechanical errors in his writing, as shown by ets, 51.2.9, for est, Cessasare, 52.2.1, for Caesare, and stertertios, 68.2.5, for sestertiōs).

In the Isola Sacra inscriptions, there is one example of coniuge (IS 249, second–third century AD) in place of dative coniugī ‘for his wife’. There are no other substandard features in this short text, but perhaps this is a slip into the ablative (or even the accusative with omission of final <m>) rather than an old-fashioned spelling. The dative ending is spelt with <i> in merenti ‘deserving’.

A much more complicated situation arises where <e> represents short /i/ from long /iː/ by iambic shortening (see p. 42) or other types of shortening. This could be an old-fashioned spelling, reflecting the mid-point of the development /ɛi/ > /eː/ > /iː/. But from the first century AD onwards, at least some speakers in certain contexts use <e> for /i/, presumably due to a lowering of /i/ to [e] and the raising of (original) /ɛː/ to /eː/; with the loss of vowel length distinctions these phonemes would end up falling together as /e/ in the precursor of most Romance varieties (see p. 40). In cases where original /ɛi/ > /eː/ > /iː/ underwent iambic or other types of shortening, it is then difficult to tell whether <e> for <i> is old-fashioned or substandard, and each example needs careful investigation.

Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 51–5) entertains the possibility that several <e> spellings in the Rustius Barbarus and Claudius Tiberianus letters may be old-fashioned, and notes the following observation by Quintilian:

“sibe” et “quase” scriptum in multorum libris est, sed, an hoc uoluerint auctores, nescio: T. Liuium ita his usum ex Pediano comperi, qui et ipse eum sequebatur. haec nos i littera finimus.

Sibe and quase are written in the books of many authors, but I do not know whether this is what the authors intended: I have learnt from Pedianus – who followed him in doing this – that Livy used these spellings. We write these words with a final i.

Quintilian clearly thought this spelling was old-fashioned (in addition to what he says in this extract, it forms part of a list of archaic spellings), and Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 54) follows him, saying that ‘[i]t is inconceivable that Livy and other literary figures used such spellings as a reflection of a proto-Romance vowel merger that was taking place in speech. They must have been using orthography with an old-fashioned flavour to it’.Footnote 15 According to Adams, use of <e> is retained from the time when sibi was still /sibeː/.

However, I have my doubts about this. Quintilian himself is aware, as shown by his comment ‘sed, an hoc voluerint auctores, nescio’, that it was possible for an author’s spelling to become corrupted by subsequent copyists (as noted by Reference De MartinoDe Martino 1994: 743). It is striking that the examples given by Quintilian are of <e> in absolute word-final position. Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 51–62, 67) has identified /i/ in closed word-final syllables as showing evidence of lowering to [e] in the first and second centuries AD. The apparent frequency of <e> in words like tibe and nese might instead be taken as showing that this lowering also affected /i/ in absolute word-final position. If lowering of /i/ to [e] had already happened, at least in words like sibi and quasi, by the first century AD, it is not impossible that it could have entered the manuscript tradition of earlier literary authors by the time of Quintilian.

In either case, it is probably not coincidental that the words in question all involve final /i/ resulting from iambic shortening. If Adams is right that this is an archaism, the old-fashioned spelling could have been retained in these words because iambic shortening applied to forms like /sibeː/ and produced a variant /sibe/; after /sibeː/ became /sibiː/ (and then /sibi/) the standard spelling sibi followed, but sibe remained as an alternative spelling.Footnote 16 This would explain, for example, why <e> is only found to write synchronic short /i/ in tibe in the Rustius Barbarus letters, despite a large number of instances of synchronic /iː/ < /ɛi/, which is what we might expect an old-fashioned use of <e> to represent. If, on the other hand, <e> in these words is due to lowering of /i/ in final syllables, it is also not surprising that the examples are in originally iambic words: iambic shortening of /iː/ is one of the very few sources of absolute word-final short /i/ in Latin.

The explanation by lowering seems particularly likely in the case of the Rustius Barbarus letters. As Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 55) notes, ‘these letters are very badly spelt, with no sign of hypercorrection or other old spellings, and there is an outside chance that tibe here is a phonetic spelling’. We find 4 examples of the spelling tibe (CEL 73, 74, 76, 77) for tibi beside 8 of tibi (these are the only examples of absolute word-final short /i/ in the letters). This compares with 4 (certain) examples of <e> for /i/ in final closed syllables of a polysyllabic word (scribes for scrībis ‘you write’, CEL 74, scribes, mittes for mittis ‘you send’ 75, scribes 76),Footnote 17 and 6 examples with <i> (dixit, enim 73, talis, leuis 74, possim 75, traduxit 77). The rate at which <e> is written for /i/ in these contexts is therefore almost identical,Footnote 18 so it makes sense that the same explanation, lowering of /i/ to [e] in final syllables, should apply to both. Consequently, it seems more probable that the tibe spellings are substandard rather than old-fashioned.

The same explanation could pertain in most of the other examples of <e> for /i/ by iambic shortening in the corpora, and cannot be ruled out in any of the examples I now discuss, from the tablets of the Sulpicii, the Isola Sacra inscriptions and the Vindolanda tablets.

In the tablets of the Sulpicii we find ube for ubi < ubei ‘when’ in the chirographum of Diognetus, slave of C. Novius Cypaerus (TPSulp. 45.3.3, AD 37). Although there are no other examples of <e> for /i/ in final syllables, Diognetus also spells leguminum ‘of pulses’ as legumenum, suggesting that /i/ may have been lowered to [e] more generally in his idiolect (although short /i/ is otherwise spelt correctly several times, including in a final syllable in two instances of accepit).Footnote 19 There are two examples of sibe in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, and these too are likely to be due to lowering. IS 27 contains several other substandard spellings, including Terenteae for Terentiae, filis for filiīs, qit for quid, aeo for eō. IS 337 has mea for meam and nominae for nōmine. These may reflect carelessness on the part of the engraver rather than lack of education, since mea comes at the end of a line (and in space created by erasure of a previous word or words), while nominae follows poenae and looks like the result of eyeskip. But the same carelessness could presumably have allowed <e> to be used, reflecting his pronunciation, instead of <i> in his copy of the text.

In the Vindolanda tablets ụbe (Tab. Vindol. 642) for ubi is the only instance of <e> for short word-final /i/.Footnote 20 The spelling in this tablet seems otherwise standard, and note in particular an instance of ṭibi. Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 91; Reference Adams2003: 533–5) has emphasised the general lack of confusion between /i/ and /eː/ in the Vindolanda tablets. But given that this appears to be the only text written in this hand, it was probably not written by a Vindolanda scribe,Footnote 21 and that it has no other examples of /i/ in a word-final syllable, we cannot be absolutely sure that <e> is not due to lowering rather than being old-fashioned.

The final case of <e> for short final /i/ is nese (P. Mich. VIII 468/CEL 142, and CEL 143) for nisi in the Claudius Tiberianus archive. Could this be due to lowering? In 468/142, there are two other instances of <e> for <i>, both in a final syllable: uolueret for uoluerit ‘(s)he would have wanted’ and aiutaueret for adiūtāuerit ‘(s)he would have helped’ (beside 3 cases of <i>: nihil, [ni]hil, and misit). But apart from nese there are 10 examples of short /i/ spelt <i> in an open final syllable: tibi (twice), [ti]bi, ṭibi, mihi (4 times), [mih]i, sibi. In CEL 143, written by the same scribe, apart from nese there are no other instances of <e> for /i/, and 5 of short /i/ in an open final syllable: tibi (twice), mihi (twice), miḥi. On the one hand, therefore, the writer of these texts did seem to have lowering in word-final syllables followed by a consonant. On the other, nese is the only example of possible lowering of /i/ in absolute word-final position, compared to 15 examples spelt with <i>. I am not certain whether use of <e> is due to lowering or is old-fashioned.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the letters include some further instances of <e> being used for /i/ which are not due to iambic shortening but could also reflect old-fashioned spellings. The first vowel of sene (468/142) for sine was originally /i/, but the writer may have thought of sine as being connected with sī ‘if’. A hypercorrect spelling seine (CIL 12.583), presumably resting on this false etymology, is attested in the second century BC. The forms nese, nesi in 468/142, and nese in 143 also have <e> for /i/ in their first syllable. This could be an old-fashioned spelling accurately reflecting original /ɛ/ here, since nisi probably came from *ne sei̯ (Reference FriesFries 2019: 94–7). The spelling nesei is attested in the two copies of the Lex luci Spoletina (CIL 12.366 and 12.2872, probably from the mid-second century BC), and nesi is mentioned by Festus (Fest. 164.1).Footnote 22 Alternatively, it could be a hypercorrection, with analysis of the ni- in nisi as being derived from the alternative negative nī < /neː/ < /nɛi/.

However, given that the writer (or author, dictating) of the text does have lowering of /i/ to [e], at least in final syllables followed by a consonant (i.e. in a position of minimal stress: Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 60), it is still possible that it is lowering that is to blame for the spelling with <e> in sine, nese, nesi, especially because these are function words, which are particularly likely not to receive phrasal stress (see p. 42), and hence might have undergone the same lowering seen in the final syllable despite not being in the final syllable of the word.

There is not enough evidence to draw completely certain conclusions. However, I do not think that we can be sure that the various types of <e> for /i/ used by the writer of P. Mich. VIII 468/CEL 142 and CEL 143 are to be attributed to old-fashioned spelling (which would be of several different types). I would be inclined to explain all instances as due to lowering of /i/ to [e] in relatively unstressed position (in function words and in final syllables).