One of the most-frequently cited challenges for early career clinician-scientists is the lack of mentoring and protected time for research or grant writing [1]. These challenges are exacerbated in IDeA (Institutional Development Award) states, which have historically low success rates when competing for National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds [Reference Snowden, Darden, Palumbo, Saul and Lee2]. The IDeA state program, established in 1993 by NIH, provides funds to build infrastructure and develop faculty to compete successfully for federal clinical and translational biomedical research funding (https://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/DRCB/IDeA). Delaware began leveraging IDeA funds with an IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) award in 2001, which catalyzed a quadrupling of NIH funds to the state over the following decade. Since 2013, a group of academic and healthcare institutions in Delaware (University of Delaware, ChristianaCare, Nemours Children’s Health, and, beginning in 2018, HBCU Delaware State University), along with the Medical University of South Carolina, have held an IDeA Clinical and Translational Research award, supplemented with Delaware state funding (DE-CTR Accel). This award aims to increase NIH funding of IDeA-state clinical and translational research by providing clinician-scientists with pilot funding, professional development, and research infrastructure.

The DE-CTR Accel Professional Development Core created the Mentored Research Development Award (MRDA) to support early career investigators. This award program has a short time frame (up to 6 months) and more focused scope (establish a mentoring team, submit one grant) than early career programs documented in the literature [Reference Hall, Mills and Lund3–Reference Ognibene, Gallin, Baum, Wyatt and Gottesman5]. This brief and focused support is crucial to efficiently launch research careers in the IDeA state context, where investigators have limited access to experienced mentors and few opportunities to offset clinical, teaching, or administrative responsibilities to engage in effective grant-writing. Here, we describe the MRDA program and outcomes from 55 participants over the first eight years.

Method

One to two times per year, a call for MRDA proposals was disseminated by email and the DE-CTR Accel website. Faculty who fulfilled the NIH criteria for a “New Investigator” were eligible to apply. In the application, investigators 1) described their intended research project (2-page summary) and a targeted grant mechanism, 2) identified at least one mentor from a DE-CTR institution, 3) detailed an MRDA-specific mentoring plan and a 5-year individualized professional development plan, and 4) described how they would use the offset and additional resources (e.g., statistical consultation, training). These application components were reviewed by 2-3 senior investigators affiliated with the Accel Professional Development Core, with one of the most important considerations being the likelihood of successful grant submission given the proposed plan (see supplemental materials for review criteria). Most investigators who participated were aspiring Principal Investigators working to launch an independent research program. For many MRDA recipients, the targeted grant submission was a career-appropriate pilot grant application through an IDeA state mechanism, institutional training award, or foundation, with the goal of then pursuing R or K mechanisms through NIH.

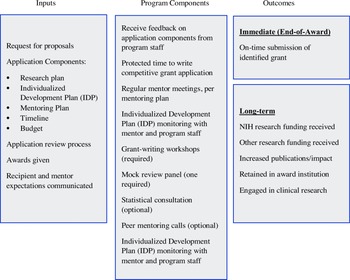

MRDA recipients requested funds to protect up to 208 hours of their nonresearch time to work on a specific grant submission. Half of the support was provided through the Accel Professional Development Core, with the remaining support from the investigator’s department. This split support was meant to ensure the commitment of the department to the investigator’s research program. In the application, investigators explained their need for protected time, described how they would structure the time (most frequently 20% effort for six months), and provided evidence that their department/division leader committed to release their time. The primary activity during the award period was grant writing, overseen by regular mentor–mentee meetings. Mentors were not compensated but were provided a stipend for education or travel ($2,250). An individualized career development plan further supported MRDA recipients with NIH grant-writing workshops (1-3 hours total, required, sample topics in supplemental materials), peer mentoring groups (weekly 20-minute calls, optional), and grant review sessions (minimally, one mock study review, required). The goal was for all awardees to submit a grant proposal at the end of the award. Fig. 1 depicts the logic model for the MRDA program, including program components.

Figure 1. Mentored research development award (MRDA) logic model.

Data for the evaluation are from administrative records and a program evaluation survey sent to all DE-CTR Accel participants from 2013-2021. Administrative records indicated grant successes proximal to program completion. The evaluation survey requested lists of publications and grants submitted or received after receiving the MRDA and about satisfaction with the MRDA program (survey in supplemental materials). We used publicly available data to determine the amount of NIH money awarded to MRDA recipients. All analyses were descriptive. These program evaluation procedures were determined to be exempt from IRB oversight by the Nemours Children’s Health and University of Delaware IRBs.

Results

From 2013 to 2021, the MRDA program received 76 applications. Of these applications, 55 investigators from four institutions were awarded 58 MRDAs. Three investigators completed two MRDAs. Findings are reported at the investigator level, using data from the first MRDA for those who received two awards. Of the 18 applications that were not awarded, five were revised and subsequently funded, and five were not awarded for administrative reasons (e.g., not eligible or left institution). Eight applications were never awarded due to concerns about feasibility of the project. Of the 55 MRDA recipients, 46 responded (84%) to the program evaluation survey between October 2021 and March 2022.

Recipient and Project Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the MRDA recipients and projects. Recipient demographic data was not routinely collected. As is typical for aspiring junior investigators across the DE-CTR, before receiving the MRDA, recipients did not have sufficient protected time for grant-writing activities.

Table 1. Mentored research development award (MRDA) recipients and projects 2013-2021

Data summarizes first MRDA for the three investigators who received two awards. Clinical degrees included MSW, MS Exercise Science, PsyD. Master’s degrees included MPH, MSCE, MSc, MTR, MSPH.

Grant Submissions and Awards

Fourteen investigators applied for but never received an MRDA. None of these investigators received NIH funding from 2014 to 2021. Before receiving their MRDA, only seven of the 46 survey respondents (15%) had ever received research funding (3 foundation, 3 NIH training/career development, 1 NIH R25, 4 IDeA mechanisms, 2 other federal).

Program outcomes related to grant submissions and awards are detailed by cohort in Table 2. Over half of MRDA awardees (n = 26, 57%) submitted a grant application associated with the award; 17 of these grants (65%) were funded. An additional four MRDA awardees who were not successful with their MRDA-targeted grant proposal had success with a subsequent grant proposal after completing the program. When considering any grant submission (i.e., MRDA-targeted or not), 67% of MRDA awardees (n = 31) submitted at least one grant proposal, and 84% of those (n = 26) received funding for their proposed research.

Table 2. Mentored Research Development Award (MRDA) recipients grant award outcomes

a Mechanisms included IDeA pilot grants (18 awards), other small IDeA support, foundation grants (9 awards), institutional training grants (4 awards), PCORI and HRSA funding.

b Only awards for research activities. Mechanisms included: K08, K23, K01 (6 awards); P20 COBRE target investigator (6 awards); R01, R15, R41, R21 (6 awards); 1 opioid supplement.

c One large NIH award (∼$4 million) to a team including an MRDA recipient was excluded from all calculations because the recipient’s role was administrative on the awarded project.

d Direct costs from NIH RePORTER, except for VA grant costs reported by PI.

Publicly available data from NIH RePORTER (https://reporter.nih.gov) indicate that after receiving their MRDA, 15 of the 55 recipients (27%) received funding as a PI for research projects from NIH, AHRQ, or the VA. Awards included career development (K awards = 6) and research projects (R01 = 2; COBRE P20 = 6; Other R = 4). The total amount of funds from these sources (direct costs) awarded to these individuals from 2014 to 2021 was ∼$9.2 million. Fourteen of the 15 projects and associated indirect costs were awarded to the same institution where these scholars had received their MRDA.

National Rates of NIH Funding During Same Time Frame

Publicly available data show success rates from 2014 to 2021 for Early Stage Investigators were 30%–33% for Career Development Awards (K) and 15%–18% for R01 applications.

Research Productivity

All 46 survey respondents (100%) indicated they had completed at least one research product since receiving their MRDA that was directly related to their award. In addition to the funding productivity described above, investigators reported publications (n = 38, 83%), presentations (n = 40, 87%), and other research products (n = 6%, e.g., nonfunded studies or research collaborations). Only two respondents (4%) indicated they were no longer conducting any research. Details are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Satisfaction with Support Received

Of the survey respondents, 96% (n = 44), somewhat or strongly agreed that the MRDA support positively impacted their career. Eighty-nine percent (n = 41) indicated they somewhat or strongly agreed that the support they received advanced their research. And 91% (n = 42) reported that the support improved their research skills.

Retention in Award Institution

Administrative records revealed that 43 of the 55 MRDA recipients (78%) remain employed at their award institution. The percentage of MRDA recipients retained in their institution varied across the four sites, ranging from 100% to 56%.

Cost of Program Administration

The average cost of salary and benefits support for the MRDA program was $17k per MRDA recipient for the DE-CTR and a matching $17k from the investigator’s department. For the period covered by this evaluation, this represents a total cost of 58 × $34k = $1.9 million. Additional program costs specific to the MRDA program are difficult to estimate, given personnel contribute to both the MRDA and the broader DE-CTR Accel Professional Development Core. We estimate the program requires a program administrator (0.2 FTE) and one or two faculty (0.2 FTE total) to lead the mentoring and training components.

Discussion

The MRDA program supported junior clinician-scientists in preparing competitive grant applications in a context with limited preexisting research infrastructure. Most applicants received and executed an MRDA, with a high proportion of them receiving follow-on funding. Almost all MRDA recipients who responded to the evaluation survey (96%) reported the award positively impacted their careers. The rate of NIH funding for all MRDA recipients (27%) was within the range of national rates of K and R funding (15%–33%) during the same time period. The NIH funds alone (∼$9 million) brought in by these scholars indicate a substantial return on investment. This kind of programming is essential for success in under-resourced IDeA states and territories, which serve highly vulnerable populations in need of further research and improved access to quality health care.

Limitations

Most limitations were related to the IDeA state context, such as limited infrastructure, software, personnel, and institutional knowledge to support research activities. Most importantly, the evaluation data were retrospective and self-reported by recipients, which is not as accurate as real-time monitoring and resulted in missing information for nine nonresponders to the survey. Of these nine individuals, four (44%) had left their institution and only one (11%) had received a follow-on NIH grant, suggesting this group received less adequate support from the MRDA. Further, we had limited opportunity to use a comparison group, no access to sociodemographic data, and insufficient capacity to monitor how recipients used their protected time. As a result, we did not have access to process data, such as how many grant writing workshops or mentor–mentee meetings a recipient attended.

While the MRDA seems to have been successful in increasing the success rate of grant applications, there were many recipients who did not submit a grant as intended. Anecdotally, reasons for not submitting applications were highly individual. For example, several investigators decided the initial target mechanism was no longer a good fit. For others, the time protected by the MRDA was insufficient for them to complete and submit a competitive application. Learning more about barriers to submitting grants may suggest further adjustments to the program.

Future Directions

As others have noted [Reference Hall, Mills and Lund3,Reference Andriole and Wolfson6], continued follow-up of award recipients is critical to monitor longer term outcomes. With increasing infrastructure, we are positioned to routinely collect sociodemographics, process data, and long-term outcomes to better understand what components of the MRDA are most impactful for whom. To reduce burden on program administrators and decrease the need for self-reporting, we are piloting Flight Tracker, an extension of the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [Reference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde7] technology (https://redcap.vanderbilt.edu/plugins/career_dev/consortium/brief.php). Further, a future opportunity for improving the program is to assess mentors’ perceptions. In addition, although the efforts described here focused on principal investigators, moving forward MRDA programming will also support co-investigators and monitor outcomes for the co-investigator role.

Conclusions

The model of providing short-term, focused “just-in-time” support for grant-writing may help IDeA institutions support early career clinician-scientists. The MRDA provides the time, resources, and accountability structures needed to execute investigators’ grant-writing plans. To effectively track program outcomes, we recommend building in automated processes for tracking use of program components and resulting research productivity for all researchers within an institution.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2023.625.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Evaluation Core of the Delaware CTR Accel Program, led by Susan Giancola, PhD, for ongoing support in collecting evaluation data.

Funding statement

This manuscript and the MRDA program are supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941 (PI: Hicks)

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This evaluation study was determined to be exempt by the Nemours Children’s Health IRB.