INTRODUCTION

Bargaining is central to politics. Politicians are engaged in near-constant negotiation with different actors, including fellow politicians, citizens, and other stakeholders, and these interactions directly shape government structures, legislation, policies, institutions, and resource distribution. Bargaining by politicians takes many forms: it is sometimes formal, as when negotiating a trade or labor agreement, or when forming a governing coalition. Other times it is informal, for example, when bargaining with colleagues over the content of legislation, or “trial-ballooning” policy ideas to citizens and assessing their receptivity. Political bargaining also varies by whether it takes the form of a one-shot affair or of repeated interactions. Politicians are required to bargain both with those who share their broad goals—that is, co-partisans and/or coalition partners—and with those who oppose them, such as political rivals.

Given the centrality of bargaining to politics, it has unsurprisingly been the focus of substantial work across subfields in political science, including international relations (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1981; Fearon Reference Fearon1998; Hafner-Burton, LeVeck, and Victor Reference Hafner-Burton, LeVeck and Victor2017; LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014; Reiter Reference Reiter2003; Wagner Reference Wagner2000), legislative studies (Austen-Smith and Banks Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988; Baron Reference Baron1991; Fenno Reference Fenno1962; Fowler Reference Fowler2006b; Strøm Reference Strøm1994), electoral studies (Blais and Indridason Reference Blais and Indridason2007; Hibbing and Alford Reference Hibbing and Alford2004; Lupia and Strøm Reference Lupia and Strøm1995), and theories of democracy and policymaking (Leach and Sabatier Reference Leach and Sabatier2005; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1988). There is a rich literature on bargaining in politics, which we revisit below. Despite the breadth of this work, there are limits to how much we know about how elected politicians bargain, for at least three reasons. First, much of bargaining happens behind closed doors, so the details, contents, and structure of negotiations are often unknown. What is revealed and available to researchers will often be nonrandom or strategic in its disclosure, or, often, simply the outcome of these bargaining processes. Second, the choice to engage in negotiations is itself nonrandom or otherwise susceptible to selection pressures. Politicians are not randomized to different matters of conflict and debate, and so in seeing how they behave in some situation, selection pressure and strategic elements keep us from understanding why they are making the decisions they make. Third, it is difficult to recruit politicians into the controlled settings that are normally used for studying bargaining in the social sciences, where research is typically conducted with non-elites (Christiansen and Kagel Reference Christiansen and Kagel2019; Frechette, Kagel, and Morelli Reference Frechette, Kagel and Morelli2005; Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze Reference Güth, Schmittberger and Schwarze1982). Taken together, these factors bound our knowledge on how politicians make decisions when they engage in bargaining.

In this paper, we report results from an experimental study fielded with sitting politicians in five countries in which we provide a first systematic exploration of political bargaining. We begin by investigating how politicians bargain with co-partisans versus the partisans of other parties—what we term “partisanship effects” in the paper. There are obvious reasons to expect partisan affiliation to matter in bargaining: parties are central to the organization of formal politics and to the running of elections; they shape and are shaped by the ideology and preferences of those who support them, let alone those who serve as their representatives (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995), and those positions and interests define the substance of political negotiations. Party attachment is also a strong source of social identity, one that reflects shared commitments between members (Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004), and sometimes deep concern for in-group members and antipathy toward out-partisans, as has been extensively documented in the literature on partisan affective polarization (Fowler and Kam Reference Fowler and Kam2007; Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). How does this central feature of politics shape elite bargaining? Does partisanship completely over-determine how politicians approach each other and citizens in negotiations, and if not, when is it more important? Direct evidence on these questions is surprisingly scant.

We also explore how partisanship matters when politicians bargain with each other versus how they bargain with citizens. Politicians regularly engage in bargaining with one another—to pass legislation, to secure advanced positions, and to increase their chances of reelection, among other things (Austen-Smith and Banks Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988; Baron and Ferejohn Reference Baron and Ferejohn1989; Diermeier and Fong Reference Diermeier and Fong2011; Strøm, Müller, and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008). However, they bargain with citizens on an equally regular basis—they propose to pursue certain policy agendas, and in doing so, they ask for support from the public in the eventual form of votes (Hibbing and Alford Reference Hibbing and Alford2004; Kedar Reference Kedar2005; Lupia Reference Lupia1992; Romer and Rosenthal Reference Romer and Rosenthal1978). Do politicians react to partisan cues similarly when bargaining with these two groups, or do they result in divergent reaction depending on the role of the bargaining target?

To study the effects of these two features, we recruited more than one thousand sitting politicians in Belgium, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, and the United StatesFootnote 1 to participate in a series of modified ultimatum games—a canonical instrument in the study of bargaining behavior, and certainly one of the most frequently used designs, having been deployed in hundreds of studies (Güth and Tietz Reference Güth and Tietz1990; Nowak, Page, and Sigmund Reference Nowak, Page and Sigmund2000; Oosterbeek, Sloof, and Van De Kuilen Reference Oosterbeek, Sloof and Van De Kuilen2004). In the game, a sender is given some sum of money. They make an offer of a share of that money to a receiver. The receiver can choose to accept that proposal—leaving the sender with the remainder—or can refuse it and cancel payment to both players. The properties and empirical regularities of the game are well known; they map onto many legislative scenarios; and the game has been the cornerstone of several classic theoretical models of legislative bargaining (Frechette, Kagel, and Lehrer Reference Frechette, Kagel and Lehrer2003; Romer and Rosenthal Reference Romer and Rosenthal1978). While ultimatum games certainly do not capture the full spectrum of bargaining scenarios that politicians encounter, their prominence in the literature on legislative bargaining makes them the most natural departure point for our empirical investigation. Importantly, the ultimatum game formally simulates one-off, short-term negotiation dynamics, potentially making it less useful for observing long-term patterns or analyzing repeated interactions, yet it still captures a substantial proportion of what constitutes political bargaining (Sulkin and Simon Reference Sulkin and Simon2001); it is especially useful for the study of elite bargaining (LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014);Footnote 2 and it is particularly well suited to capturing beliefs about an offer that the other party will accept or make, which is the core bargaining outcome we are interested in evaluating. In our version of the game, we implement a between-subject experimental design to control for the target’s partisanship relative to the respondent, allowing us to directly evaluate how this feature impact politicians’ bargaining behavior. We also control for whether the bargaining target is a fellow politician or a citizen, allowing us to assess whether partisanship is factored differently by politicians in these two scenarios. Our work represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first study of the ultimatum game with sitting politicians as participants.

What we find has important implications for both our understanding of how politicians bargain with each other and for our understanding of partisanship. We document large and important partisanship effects: overall, politicians display a consistent favoritism toward co-partisans. When paired with a co-partisan compared with a supporter of another party, they offer more and they demand less. We further find that the degree of partisan discrimination is conditioned by the identity of the bargaining partner. Politicians propose far more and demand far less from co-partisan citizens (relative to out-partisans) compared with how partisanship information alters their behavior when faced with co-/out-partisan colleagues. This results in partisanship effects on bargaining that are about half the magnitude of those estimated when the targets are citizens. In our findings, partisanship appears to matter markedly less when the target is a fellow politician than it does when politicians engage non-elites.

Our findings are consistent across all our five country cases. They have important implications for how we understand politicians as bargainers. First, our findings inform and expand the ongoing debate on the quality of politicians’ in-office decision-making (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Hafner-Burton, Hughes, and Victor Reference Hafner-Burton, Alex Hughes and Victor2013; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2020; Sheffer et al. Reference Sheffer, John Loewen, Walgrave, Soroka and Shaefer2018). Bargaining has so far been left largely unexplored in studies of elites’ cognitive biases and choice heuristics, and we contribute to this literature by demonstrating that politicians’ logic in ultimatum bargaining systematically shifts in predictable ways in response to partisan cues, and that these patterns are stable across countries and levels of representation. Second, they provide supportive experimental evidence for, and elaboration on existing sociological accounts of cooperative norms between politicians (Fenno Reference Fenno1962; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1989). As a result, the findings reported here help us better understand how legislative institutions fulfill one of their core theorized roles, which is to facilitate cooperation among members (Best and Vogel Reference Best and Vogel2014; Döring Reference Döring1995; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999), a function that is especially worthy of attention on the backdrop of recent accounts that highlight the role of politicians as spearheading patterns of affective polarization and partisan animosity (Brownstein Reference Brownstein2008; Fiorina and Levendusky Reference Fiorina and Levendusky2006; McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2016).

This paper is organized as follows: in the following section, we expand the theoretical basis of our paper. We then review our instrument and sample in the Methods section, followed by a presentation of the results. We then return to the implications of our findings, before concluding.

THEORY: ELITE BARGAINING

What Do We Know About How Politicians Bargain?

Bargaining is inherent to legislative politics.Footnote 3 In existing accounts, the outcomes of legislative bargaining are most often seen as being strongly governed by institutional and structural conditions. Partisan affiliation and opposition/coalition status alongside existing issue positions shape executive behavior and decisions on voting and policy substance (the literature is vast, but see, e.g., Baron Reference Baron1991; Huber and McCarty Reference Huber and McCarty2001; Laver, Laver, and Shepsle Reference Laver, Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2004; Müller and Strom Reference Müller and Strom2003), and political power and the rules of the electoral system determine who is able to force their will in negotiations, whether they concern legislation, coalition formation, election timing, intraparty dynamics, or career prospects (Austen-Smith and Banks Reference Austen-Smith and Banks1988; Baron and Ferejohn Reference Baron and Ferejohn1989; Diermeier and Feddersen Reference Diermeier and Feddersen1998; Gamson Reference Gamson1961b; Kam Reference Kam2009; Lupia and Strøm Reference Lupia and Strøm1995; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2003; McKelvey and Riezman Reference McKelvey and Riezman1992; Persson, Roland, and Tabellini Reference Persson, Roland and Tabellini2007; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Tsebelis and Money Reference Tsebelis and Money1997; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2001).

These determinants undoubtedly play a major role in constraining and shaping how legislative negotiations unfold and conclude. Yet, political bargaining is a process that is rooted in individual-level decision-making: it is done by specific politicians and those they negotiate with, and as such it is a profoundly interpersonal, socializing, and transactional process (Best and Vogel Reference Best and Vogel2014; Caldeira and Patterson Reference Caldeira and Patterson1987; Fenno Reference Fenno1962; Kirkland Reference Kirkland2011; Peoples Reference Peoples2008; Reingold Reference Reingold1996), and its outcomes are often shaped by individual shortcomings of information neglect and misreading of intentions (Sabatier, Hunter, and McLaughlin Reference Sabatier, Hunter and McLaughlin1987; Strøm Reference Strøm1994), and dynamics of trust formation (Leach and Sabatier Reference Leach and Sabatier2005). Perhaps most importantly, how well politicians bargain carries very direct career implications for them: politicians are in the business of realizing policy goals—often far reaching in scope, duration, and cost. For them to realize these goals, they almost inevitably have to negotiate with each other (and with other actors) in order to form legislative coalitions and gain executive support.Footnote 4 Their ability to correctly identify the intentions and logic of others is a major factor determining their career success and ability to hold office (Rathbun, Kertzer, and Paradis Reference Rathbun, Kertzer and Paradis2017; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002), something that they are by and large deeply invested in (Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974; Przeworski, Stokes, and Manin Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). In that sense, not only is the outcome of bargaining likely dependent on the choices and competencies of individual politicians, but if any group has a strong incentive to bargain well and develop expertise in it, elected officials are among the top contenders (Hafner-Burton, Hughes, and Victor Reference Hafner-Burton, Alex Hughes and Victor2013; LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014).

Because the choices politicians make translate directly into large-scale policy outcomes, and because they by definition act as representatives of citizens’ opinions and preferences, there are broader consequences for how they bargain and how they form beliefs about others in the process. How politicians negotiate is consequential for the quality and nature of democratic representation in the systems they operate in: for example, ascribing adversarial intentions and spiteful behavior to colleagues motivates uncooperative legislative behavior, which itself can lead to gridlock and policy stagnation, but also to heightened levels of political polarization inside legislatures (Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Ingold, Sciarini and Varone2016; Leach and Sabatier Reference Leach and Sabatier2005). Moreover, because citizens are responsive to elite messaging and behavior, these processes run the risk of contributing to heightened levels of affective polarization in the general population (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018; Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Rogowski and Sutherland Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016). Conversely, if politicians believe that their peers are largely utilitarian and/or act fairly and cooperatively, this could facilitate opposite patterns, both in terms of concrete policy outcomes and public perceptions of legislative politics. This is likewise relevant for how politicians perceive the expectations of citizens: if they believe the public to be more polarized based on partisan lines, or more distrusting or spiteful of others and of government, this could well affect the kinds of policies politicians are willing to pursue and how they bargain over them (Broockman et al. Reference Broockman, Carnes, Crowder-Meyer and Skovron2021).Footnote 5

In sum, politicians operate in a high-stakes environment where forming accurate beliefs about others is consequential for the success of the many forms of bargaining they engage in, and as a result, for their professional trajectories and for the policy outcomes of parliamentary politics.

Insofar as bargaining matters for politicians’ policy and career goals, they have a strong incentive to engage in bargaining strategically and (from their perspective) successfully: that is, if they identify agreement as a desirable outcome, they should be able to act purposively to reach it, given what they know about the interests of the other party. If they identify conditions under which avoiding agreement is preferable, they should be able to act to avoid compromise (and, arguably, to construct a favorable narrative around it that serves their goals). Indeed, evidence on experts from nonpolitical domains suggests that experience breeds more strategic behavior when interacting with peers (Chiappori, Levitt, and Groseclose Reference Chiappori, Levitt and Groseclose2002; Fehr and List Reference Fehr and List2004; List Reference List2003; Muller et al. Reference Muller, Sefton, Steinberg and Vesterlund2008; Walker and Wooders Reference Walker and Wooders2001).

All of the above, however, does not guarantee that in practice politicians are strategic, expert negotiators. Cumulative evidence demonstrates that elected officials are often no better than non-elites in standard decision-making tasks (Kertzer and Renshon Reference Kertzer and Renshon2022; Linde and Vis Reference Linde and Vis2017), even when they directly relate to judgments that are central to their expected competencies (Sheffer et al. Reference Sheffer, John Loewen, Walgrave, Soroka and Shaefer2018). Politicians regularly exhibit a biased perception of public opinion, despite it being a core tenet of what makes them likely to be reelected (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Pereira Reference Pereira2021; Walgrave et al. Reference Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans, Soontjens, Pilet, Brack and Varone2023). And other (nonelected) policy elites who engage in similar tasks behave in ways that are often far from meeting expectations of strategic conduct or second-order reasoning (LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014; Tetlock Reference Tetlock2005).

What should we expect to observe when politicians engage in bargaining, then? Our knowledge of how individual-level dynamics play out in bargaining among politicians is surprisingly limited: reviewing the literature, LeVeck et al. (Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014, 18536) note that “much of the existing literature assumes that elites are more ‘rational’ and display fewer of the biases in beliefs, preferences, and decision making that are evident in less experienced populations. …the prevailing view is that, when bargaining, elites merely pay lip service to issues like equity while actually bargaining closer to a norm of rational self-interest.” Indeed, a large body of formal modeling research on legislative bargaining makes strong assumptions about the degree of rationality and strategic foresight of representatives, which are then used to support game-theoretic predictions or explanations of various outcomes that rely on in-office negotiations (famously, Baron and Ferejohn Reference Baron and Ferejohn1989; Gamson Reference Gamson1961b and subsequent work, but see also Bendor and Meirowitz Reference Bendor and Meirowitz2004; Dewan and Myatt Reference Dewan and Myatt2010; Dewan and Squintani Reference Dewan and Squintani2018; Winter Reference Winter1996). These accounts, by and large, expect politicians to be highly rational and strategic bargaining actors.

Large-scale empirical explorations of these theoretical accounts are rare. In the few instances when predictions of relevant theories are evaluated empirically, non-elite samples are invariably used, often reporting patterns that deviate from the predictions of the tested models, highlighting the role of variance on individual-level factors such as negotiators’ egalitarian preferences and their capacity to deal with information overload (Diermeier and Gailmard Reference Diermeier and Gailmard2006; Diermeier and Morton Reference Diermeier, Morton, Austen-Smith and Duggan2005; Frechette, Kagel, and Lehrer Reference Frechette, Kagel and Lehrer2003; Frechette, Kagel, and Morelli Reference Frechette, Kagel and Morelli2005; Gamson Reference Gamson1961a; Kagel, Sung, and Winter Reference Kagel, Sung and Winter2010; see also Peter Reference McKelvey, Peter, Enelow and Hinich1990 for a review of some earlier work). While this body of research represents an important step forward, making inferences about elite behavior from convenience samples is not without risks, because, as Druckman and Lupia (Reference Druckman and Lupia2012, 1178) put it, “typical experimental subjects often lack the experience needed to act ‘as if’ they were professional legislators.” Indeed, if politicians develop a unique type of bargaining expertise or alter their behavior in light of accumulated experience, these designs are not best-equipped to document them.

Additional work on bargaining in politics relies on descriptive case analyses that provide rich accounts of cooperative and adversarial in-office dynamics (Fenno Reference Fenno1973; Greenstein Reference Greenstein2009; Johnson Reference Johnson2009; Putnam Reference Putnam1976; Strøm Reference Strøm1994; Warwick and Druckman Reference Warwick and Druckman2006), or document the outcomes of decisions to collaborate using network analysis of legislative data (Fowler Reference Fowler2006b; Kessler and Krehbiel Reference Kessler and Krehbiel1996; Kirkland Reference Kirkland2011; Tam Cho and Fowler Reference Tam Cho and Fowler2010). But overall, these studies do not systematically theorize on how individual-level factors feature in bargaining outcomes. Rare exceptions to this exist in the long-standing (and, in the last three decades, largely abandoned) literature on socialization in parliaments that explores how antagonistic cooperation norms form (Best and Vogel Reference Best and Vogel2014; see also Caldeira and Patterson Reference Caldeira and Patterson1987; Reingold Reference Reingold1996). This literature uses large-scale observational research to identify learning and accumulated experience as causes of gradual absorption of these norms.

While controlled empirical investigations of legislative bargaining have been relatively limited, in recent years, scholars of international relations have begun to systematically explore how elites engage in practice in international negotiations and diplomacy, and what individual-level factors are in play when they do so. These works employ lab and survey experiments to identify the impact of factors such as altruism and epistemic motivation in predicting bargaining outcomes (Chilton, Milner, and Tingley Reference Chilton, Milner and Tingley2020; Kertzer and Rathbun Reference Kertzer and Rathbun2015; Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016; Rathbun, Kertzer, and Paradis Reference Rathbun, Kertzer and Paradis2017; Tingley Reference Tingley2011). Others employ sophisticated descriptive approaches to study the same phenomena (Hall and Yarhi-Milo Reference Hall and Yarhi-Milo2012; Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo Reference Weisiger and Yarhi-Milo2015; Yarhi-Milo Reference Yarhi-Milo2013). Relevant to our methodological choice, some of the most rigorous contributions in this literature directly recruit (largely nonelected) elites to participate in simulated bargaining scenarios in order to explore what role their personal characteristics play in these situations (Hafner-Burton et al. Reference Hafner-Burton, LeVeck, Victor and Fowler2014; Hafner-Burton, LeVeck, and Victor Reference Hafner-Burton, LeVeck and Victor2017; LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014; Yarhi-Milo, Kertzer, and Renshon Reference Yarhi-Milo, Kertzer and Renshon2018). This group of studies has already generated important insights on how differences among elites on qualities such as strategic reasoning and patience matter for the outcomes of foreign relations negotiations, and serve as a template for how we study determinants of bargaining by legislative elites.

It is clear then that our understanding of bargaining in politics is partial, at minimum, and is lacking empirical evidence directly collected from politicians. Here, we explore what the literature identifies—often implicitly—as one major factor that should impact how politicians bargain: how information about the partisan identification of the bargaining target impacts how politicians bargain—what we refer to as partisanship effects. We use it as the starting point for what we hope would be a more systematic empirical evaluation of the quality and substance of bargaining by politicians.

Partisanship Effects

Political parties facilitate and shape the behavior of politicians, both inside and outside legislatures. In the context of legislatures, parties serve an organizational function (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1995), allowing for the collective pursuit of shared ideological and programmatic agendas. With a few notable exceptions,Footnote 6 nearly every legislature in the world is organized around political parties, and these parties are often organized with a division of labor around portfolios or areas of expertise, enforced by varying degrees of party discipline (Bowler, Farrell, and Katz Reference Bowler, Farrell and Katz1999; Kam Reference Kam2009). Politicians have obvious incentives to work together to further collective interests of other representatives in their party, and to engage in competitive and/or adversarial behavior with members of other parties (Binder Reference Binder2004; Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Jones Reference Jones2001), and the extensive literature on the rise in elite partisan polarization has documented how these patterns increasingly dominate legislative politics and subsequently drive polarization among citizens (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus Reference Druckman, Peterson and Slothuus2013; Fiorina and Levendusky Reference Fiorina and Levendusky2006; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010).

However, politicians also rely to varying degrees on the cooperation of those in other parties, both to advance legislation (Fowler Reference Fowler2006b; Harward and Moffett Reference Harward and Moffett2010; Kirkland Reference Kirkland2011; Reingold Reference Reingold1996) and to maintain system-level legitimacy. The practice of legislative politics often involves more cooperation and compromise across partisan lines than citizens prefer or understand (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002; Ramey, Klingler, and Hollibaugh Jr Reference Ramey, Klingler and Hollibaugh2017). In sum, we should expect partisanship to matter when politicians negotiate with politician counterparts. Specifically, we expect politicians to offer more and demand less of co-partisans, but these effects should be tempered by the need to and experience of frequently working across partisan lines.

We are further interested here in evaluating whether and how partisanship matters for politicians when they engage in bargaining outside of legislatures relative to its impact within them. Outside of legislatures, there are fewer strategic constraints that limit how partisanship, as a social identity, shapes the behavior of those who hold it. To be the partisan of a party is not only or even principally to share its policy aims, but also to affirm one’s membership in other larger, social groups (Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004), to engage in collective action on behalf of others (Fowler Reference Fowler2006a; Fowler and Kam Reference Fowler and Kam2007; Loewen Reference Loewen2010), and to collectively experience an election and its subsequent status gain or loss and changes in power relations (Anderson Reference Anderson2005; Sheffer Reference Sheffer2020). Moreover, in the presence of ideological sorting, partisanship becomes a more salient and overarching social identity (Mason Reference Mason2015), as greater convergence emerges between other social identities and policy preferences. These features are important for how both citizens and politicians process and respond to partisanship, but when the latter operate within legislatures, the strategic incentives for cooperation mentioned above are expected to put those motivations in check in at least some situations.

As a result, partisan identities should, if anything, matter more when politicians bargain with non-elites than when they face politician counterparts. Politicians bargain with citizens less frequently than with one another, and when they do negotiate with citizens, it is often in the context of elections and what is on the line is first and foremost their careers (Groseclose and McCarty Reference Groseclose and McCarty2001; Kedar Reference Kedar2005; Przeworski, Stokes, and Manin Reference Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999). Therefore, for politicians, the stakes of these infrequent interactions with citizens are likely much higher than any single interaction with other politicians. Indeed, their career depends on earning votes, and knowing that a potential voter shares a candidate’s partisanship arguably provides a strong signal regarding their likelihood of responding favorably in these vote-seeking interactions. Moreover, those co-partisans are those who are most likely to reward politicians who offer them greater in-group reward. In negotiating with in-office colleagues, shared partisanship is also a strong signal of someone’s willingness to cooperate, and obviously dictates negotiation positions on many issues, but is far from being the only available heuristic, and shared interests are in some cases diffuse across party lines (Best and Vogel Reference Best and Vogel2014; Mughan, Box-Steffensmeier, and Scully Reference Mughan, Box-Steffensmeier and Scully1997). The implication, then, is that insofar as partisanship impacts politicians’ bargaining strategies, it should be more pronounced, and result in stronger behavior change, when the counterpart is a citizen compared to when they are engaging a fellow politician.

METHOD

Instrument: The Ultimatum Game

Bargaining behavior has been studied experimentally in the lab and in the field using numerous instruments. Our design utilizes a modified version of the classic ultimatum game, originally pioneered by Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze (Reference Güth, Schmittberger and Schwarze1982), which is among the most frequently employed modules in the study of bargaining dynamics, used both as a theoretical model and as an empirical method. In the game’s simplest form, two players are matched: one is assigned to be the proposer, who makes an offer to the other player on how to divide a fixed resource (usually a sum of money). The other player then decides whether to accept or reject the offer. If they accept, the money is divided according to the offer. If they reject, both players receive nothing. For simplicity, the lowest amount the other player is willing to accept (i.e., the lowest offer they will not reject) is called their demand. Hibbing and Alford (Reference Hibbing and Alford2004, 66) note that the ultimatum game “has been replicated and extended in hundreds of scholarly publications” to the point that it is a candidate for being “the single most employed experimental scenario.” The standard finding in ultimatum game experiments is that individuals act in violation of game-theoretic expectations. Rather than proposing to give nothing or the smallest amount possible, the modal proposed allocation observed empirically is 50/50, with an average amount of 30%–40% offered to the recipient. On the recipient side, rather than accepting nothing or the smallest amount possible, recipients often reject nonzero offers—about half of the time for offers that allocate them 20%–30% or less of the total amount (Camerer and Thaler Reference Camerer and Thaler1995; Cooper and Dutcher Reference Cooper and Dutcher2011; Cram et al. Reference Cram, Moore, Olivieri and Suessenbach2018; Nowak, Page, and Sigmund Reference Nowak, Page and Sigmund2000). These patterns—allocating significant proportions to recipients and rejections of low offers—are remarkably consistent across countries, societies, and contexts (Alvard Reference Alvard2004; Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Fehr, Camerer and Gintis2004; Oosterbeek, Sloof, and Van De Kuilen Reference Oosterbeek, Sloof and Van De Kuilen2004). They have been explained by a series of mutually nonexclusive interpretations: these include revenge (Nowak, Page, and Sigmund Reference Nowak, Page and Sigmund2000), enforcement of fairness expectations and punishment in face of cooperative norm violation (Bolton and Zwick Reference Bolton and Zwick1995; Mendoza, Lane, and Amodio Reference Mendoza, Lane and Amodio2014; Sanfey Reference Sanfey2009), altruism (Oosterbeek, Sloof, and Van De Kuilen Reference Oosterbeek, Sloof and Van De Kuilen2004), heuristic thinking (Calvillo and Burgeno Reference Calvillo and Burgeno2015), empathy and perspective taking (Zak, Stanton, and Ahmadi Reference Zak, Stanton and Ahmadi2007), reputation building and strategic reasoning (Hibbing and Alford Reference Hibbing and Alford2004; Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, McCabe, Shachat and Smith1994), response to structural market integration levels (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Boyd, Bowles, Camerer, Fehr, Gintis and McElreath2001), and a reflection of societal and situational power relations (Kertzer and Rathbun Reference Kertzer and Rathbun2015; Solnick and Schweitzer Reference Solnick and Schweitzer1999).

As LeVeck et al. (Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014, 18537) explain, the ultimatum game is especially relevant for the study of elite bargaining because “although the ultimatum game is stylized …the game offers the advantage of precision in measurement in a setting that makes salient the question of how players allocate a fixed sum. Because the game is widely used in the behavioral sciences, results …can be readily compared with studies on other populations.” We subscribe to this motivation here as well. Beyond generalizability and comparability, ultimatum game bargaining dynamics are directly reflective of a host of politically relevant behaviors and outcomes. In addition to its direct applicability in the context of domestic bargaining and different interactions that elected politicians have, as reviewed earlier in the paper, ultimatum-style bargaining has been used in the international relations literature as a standard model for analyzing armed conflict initiation (Reed Reference Reed2003), followed by empirical tests conducted using franchised versions of the game (Kertzer and Rathbun Reference Kertzer and Rathbun2015; Rathbun, Kertzer, and Paradis Reference Rathbun, Kertzer and Paradis2017; Tingley Reference Tingley2011), and to analyze negotiations on trade, finance, and other international agreements (Hafner-Burton, LeVeck, and Victor Reference Hafner-Burton, LeVeck and Victor2017; LeVeck et al. Reference LeVeck, Alex Hughes, Fowler, Hafner-Burton and Victor2014).

In the current study, we use ultimatum games with hypothetical stakes rather than real payoffs. This was necessary from a practical standpoint, as offering politicians monetary rewards for their participation in the game is ethically questionable and in some cases potentially illegal. While this choice may raise validity concerns, existing research comparing real and hypothetical stakes in ultimatum games finds little to no meaningful differences in behavior (Bolle Reference Bolle1990; Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze Reference Güth, Schmittberger and Schwarze1982; Hoffman, McCabe, and Smith Reference Hoffman, McCabe and Smith1996; Roth et al. Reference Roth, Prasnikar, Okuno-Fujiwara and Zamir1991; a few studies were specifically designed to assess differences in play between hypothetical and real payoff in ultimatum bargaining. They find either no differences or, at best, mixed evidence (see, e.g., Cameron Reference Cameron1999; Gillis and Hettler Reference Gillis and Hettler2007). A comprehensive review on the effects of financial incentives in experiments by Camerer and Hogarth (Reference Camerer and Hogarth1999) concludes that ultimatum games belong squarely in the category of games for which financial incentives make no difference in behavior (22–3).

We emphasize that the ultimatum game simulates one-off, short-term negotiation dynamics, making it potentially less useful for observing long-term patterns or analyzing repeated interactions. In our opinion, and as is evident in the extensive literature using it to model political dynamics, it nevertheless still captures a substantial proportion of what constitutes bargaining by politicians, and is thus especially well suited for our purpose in this study.

Application

Our use of the ultimatum game here introduces two innovations: first, we field it to sitting politicians, who have not been previously recruited to play it. Second, we introduce a novel, independently assigned experimental treatment that manipulates whether the bargaining partner our participants face shares the participant’s party identity or is a member/supporter of a rival party. We also include a second, cross-cutting treatment, in which we control for whether the bargaining partner is a colleague from the politician’s own parliament/council or a citizen. This “counterpart-type” treatment is not the focus of the current analysis, although we leverage it to evaluate the differential impact of partisanship when politicians bargain with colleagues versus citizens.

We fielded our modified version of the ultimatum game with sitting politicians as participants by embedding them in larger surveys that our participants responded to. In all cases, this module was the only one dealing with bargaining, and was the only hypothetical scenario the politicians were presented with. The game was played with hypothetical stakes, with respondents being asked to distribute (or accept/reject a distribution of) 1,000 Euros, American Dollars, Canadian Dollars, or Swiss Francs, depending on the country.

In Belgium, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland, the interviews were conducted in person, as part of the POLPOP project,Footnote 7 with participants completing the modules on tablets and laptops. In the United States, the experimental module was fielded as part of an online survey of American local- and state-level politicians, conducted by the CivicPulse project.Footnote 8 In all cases, modules were fielded using Qualtrics, with texts translated to the relevant local languages.

We used a strategy method—that is, we asked respondents to indicate both the allocation that they would propose to the other player, and the amount below which they would reject an offer made by the other player (their lowest acceptable offer—i.e., their demand). To avoid order effects, we randomized the order of strategy elicitation: half of the respondents were asked to make their proposal first and then state their demand, and the other half provided their demand first.

Experimental Treatments

In addition to randomizing the order of presentation, we included two substantive treatments that are the core moving pieces of the module. The first treatment manipulated the partisan identity of Player 2, describing them alternately as a co-partisan (“a supporter of your party” for citizens, “also a member of your party” for politicians), or an out-partisan who supports a political opponent (“a supporter of a party from the opposite side of the political map” for citizens, “a member of a party on the opposite side of the political map” for politicians). The second manipulated the identity of Player 2 in the game, describing them alternately as a citizen (in the United States: a citizen from the politicians’ locality) or as a politician from their legislature (in the United States: a politician from their locality).

In the U.S. context, candidates for local office frequently do not run on a partisan ticket: 45.5% of respondents in our sample reported not running as a member of a party, and 23.7% self-described as independents or having other party ID. To accommodate this, our partisanship treatment had three conditions, describing Player 2 as either a Democrat (“a supporter of the Democratic Party” for citizens, “a member of the Democratic Party” for politicians), a Republican, or as unaffiliated (“does not identify with any political party” for citizens, “is not affiliated with a political party” for politicians.)

The above resulted in a

![]() $ 2\times 2\times 2 $

design in Belgium, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland,Footnote

9 and a

$ 2\times 2\times 2 $

design in Belgium, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland,Footnote

9 and a

![]() $ 2\times 2\times 3 $

design in the United States. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the resulting 8 or 12 vignettes, and provided both their proposal and lowest acceptable offer.

$ 2\times 2\times 3 $

design in the United States. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of the resulting 8 or 12 vignettes, and provided both their proposal and lowest acceptable offer.

To allow for meaningful comparisons between the U.S. design and the rest of the cases, we subsequently identified the U.S. respondents as assigned to the co-partisan or out-partisan treatment based on whether they were presented with a target sharing their self-reported identity or the opposite one. We excluded respondents who did not identify as Democrats or Republicans and respondents who were assigned to see a no-affiliation target. This procedure created full congruence with the partisanship treatment in our other cases, but substantially reduced the U.S. sample used in the partisanship analysis to 343 respondents, down from 625 in the overall sample.

A sample vignette is provided below to illustrate the module. This vignette represents a propose-first, co-partisan politician target condition, of the design fielded in Belgium, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland; full vignette texts are provided in the Supplementary Material (SM):

“Consider the following hypothetical scenario. There is €1000 that needs to be divided between yourself and a politician. The money is unrelated to politics or to your work and carries no legal obligations. It is purely hypothetical. All you know about the politician is that s/he is also a member of your party.

In this scenario, you propose to the politician how to split the money.

-

• You can divide the money between you two in whatever way you like: you can take the entire amount yourself, give it all to the politician, or split it.

-

• You can only make one proposal to the politician and you cannot negotiate with them.

-

• Once you make your proposal, the politician decides whether to accept or reject the offer.

-

• If the politician accepts your offer, the money is split between the two of you according to your proposal.

-

• If the politician rejects your offer, you both get nothing.

-

• The politician will never know your identity. They only know how you propose to split the money.

What would be your proposal? Please indicate how much you would give to the politician of the €1000. The remainder is what goes to you.”

[Text box for input]

[In new page] “Now assume the politician is the one making the proposal and you are required to accept or reject their offer. Remember that if you accept, you take the amount the politician offers you, and they take the rest. If you reject, you both get nothing. What is the lowest offer that you will be willing to accept?”

[Text box for input]

Sample

We fielded the experiment with sitting politicians in Belgium, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland, with in-person interviews starting in early 2018 and largely concluding by mid-2019, and an online survey fielded in August 2018 in the United States.Footnote 10

Taken together, our five cases provide us with substantial variation across levels of government (provincial and federal in Canada; regional and federal in Belgium; and local and state government in the United States), across electoral systems, and political cultures. The normal career trajectory of politicians also varies across our cases. The results we present below suggest substantial similarity in results across all politicians, despite these national differences.

In Belgium, the experiment was fielded with 237 legislators: 88 from the Belgian Federal Parliament (out of 150 total, 59% response rate), 85 from the Flemish Parliament (out of 124, 68% response rate), and 64 from the Walloon Parliament (out of 75 seats, 85% response rate). In Canada, we recruited 50 Members of Parliament from the Federal House of Commons, Canada’s Parliament’s lower chamber (out of 338 seats, 15% response rate), and 27 Members of Provincial Parliament from the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Canada’s largest province (out of 124 seats, 22% response rate). In Germany, 74 members of the Bundestag participated (out of 709 seats, 10% response rate). In Switzerland, 96 legislators participated, from both chambers of the Swiss Federal Assembly (total of 246 seats, 39% response rate). In the United States, 625 local (

![]() $ N=356 $

), county (

$ N=356 $

), county (

![]() $ N=160 $

), and state-level (

$ N=160 $

), and state-level (

![]() $ N=109 $

) representatives participated in the experiment.Footnote

11 Basic sample descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1.

$ N=109 $

) representatives participated in the experiment.Footnote

11 Basic sample descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Note: Tenure—time in office since year of first election to current position, in years. Figures reported are sample means. Gov. exp.—cumulative number of years working as a public official. Figures reported are sample means.

RESULTS

Our quantities of interest in this analysis are the proposals made by participants to the second player, and their demands—that is, the lowest offer made by the second player that participants indicated they would still accept. Both quantities are on a scale of 0 to 1,000 (either Dollars, Euros, or Francs). For both quantities, we report raw means for groups of interest, and estimation results from regression models with the treatment variables as predictors (and country fixed effects for pooled models). We first report overall results, and then present findings on the direct effects of our experimental treatments, and on their interaction. In doing so, we describe both the effects on both proposals and demands, in that order.

Overall Findings

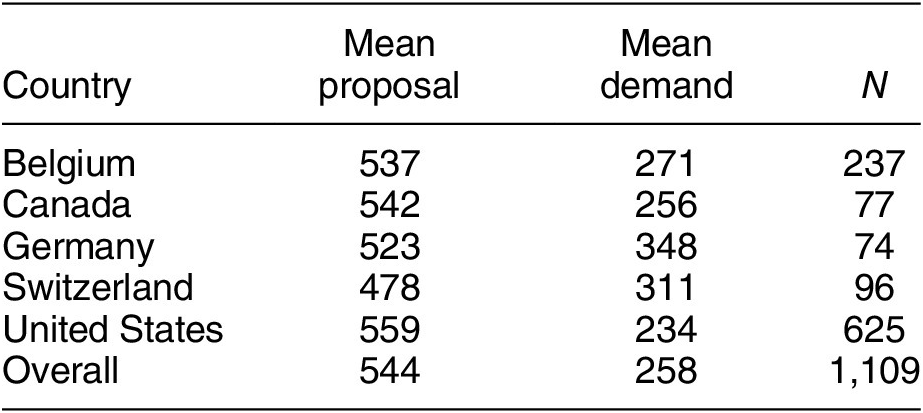

Figure 1 and Table 2 report the mean proposals and demands made by participants, across all treatment conditions. As is evident, in all countries, politicians make proposals that are on average higher than or close to half the amount they are asked to distribute, and on average report that they will reject offers that are below 25%–30% of the allocation. A breakdown of these results by whether the target in the game was a fellow politician or a citizen is available in the SM.

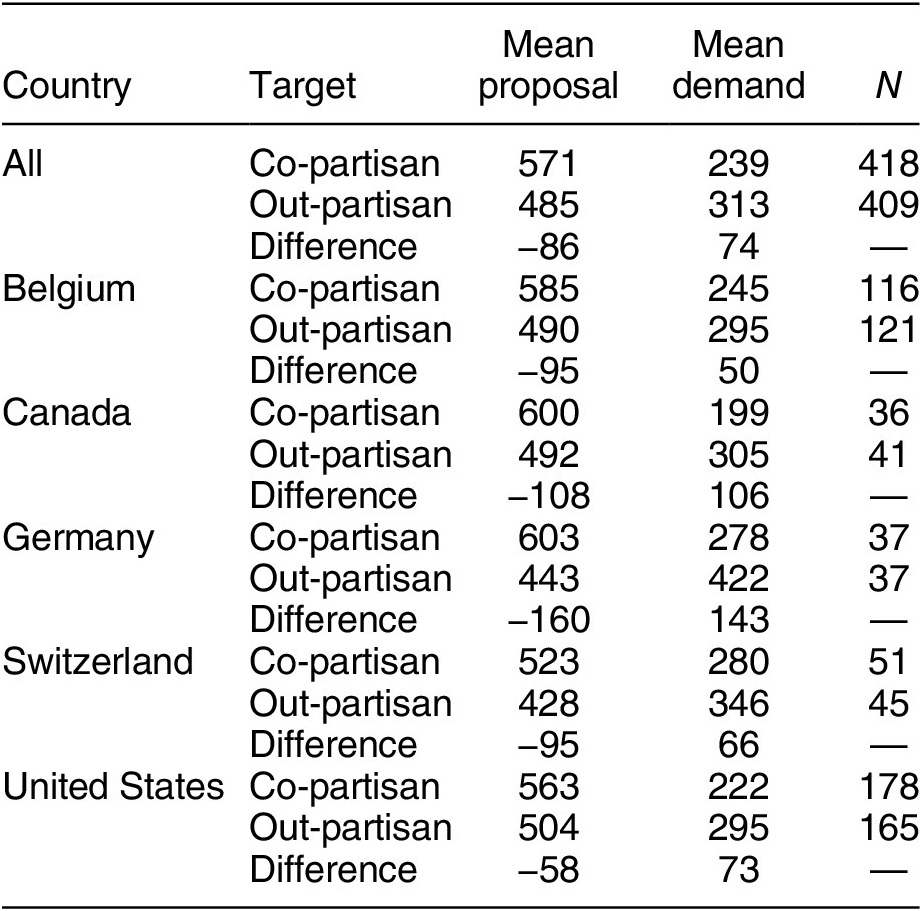

Table 2. Proposals and Demands Made by Politicians in the Ultimatum Game

Note: Figures are mean proposals and demands reported by the participating politicians, across treatment conditions. Figures reported are amounts in either Euros, Dollars, or Francs, out of 1,000.

Figure 1. Proposals and Demands Made by Politicians in the Ultimatum Game

Note: Figures are means by country. Corresponding results are reported in Table 2.

These results are perhaps best understood when compared with existing findings on how non-elites play the ultimatum game. Meta-analyses of ultimatum game studies find that proposals in industrialized societies amount to about 40%–43% of the shared pie, on average, and rarely exceed 50% (Cochard et al. Reference Cochard, Le Gallo, Georgantzis and Tisserand2021; Oosterbeek, Sloof, and Van De Kuilen Reference Oosterbeek, Sloof and Van De Kuilen2004; Tisserand Reference Tisserand2014, see also Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel and Grossman2001). The offers made by politicians in our sample are substantially higher, averaging 54% of the endowment, or 11–14 percentage points (pp) higher than those population figures. In proposals, at least, politicians opt for far more generosity compared with the general population, across all our cases. Switzerland is the only case in which the mean offer is lower than half of the endowment (48%), but it is still much higher than the non-elite mean. Moreover, and as reported in the SM, the mean offers made by politicians to citizens are even higher on average, at 60% of the endowment. Their offers to fellow politicians are lower (49%), but still well above established levels among citizens.

A comparison of politicians’ and citizens’ demands yields different patterns. First, there are surprisingly less meta-analyses of reactions to offers in the ultimatum game, compared with evidence on offers. The evidence that does exist shows that among citizens, a majority of respondents reject offers that are under 20%–30% of the pie, with rejection rates rising as the offers become lower (Camerer Reference Camerer2003; Cooper and Dutcher Reference Cooper and Dutcher2011; Nowak, Page, and Sigmund Reference Nowak, Page and Sigmund2000). Because we use the strategy method to elicit demands, we do not present respondents with a concrete offer that they are requested to accept or reject, but instead request them to state the lowest offer they will not reject. Nevertheless, using this method, we find that politicians report mean demands that are around 25%–30% of the endowment, largely in line with ultimatum game behavior among citizens. These amounts vary substantially by country, with Canadian and American politicians demanding 26% and 23% of the pie, and German politicians demanding 35%. The mean demands politicians pose to colleagues tend to be about 10 pp higher than those they present to citizens (see the SM for a full breakdown), but in all cases demands are far lower than the offers the same politicians make, a pattern that is in line with existing evidence on non-elite behavior.

The Effect of Partisanship

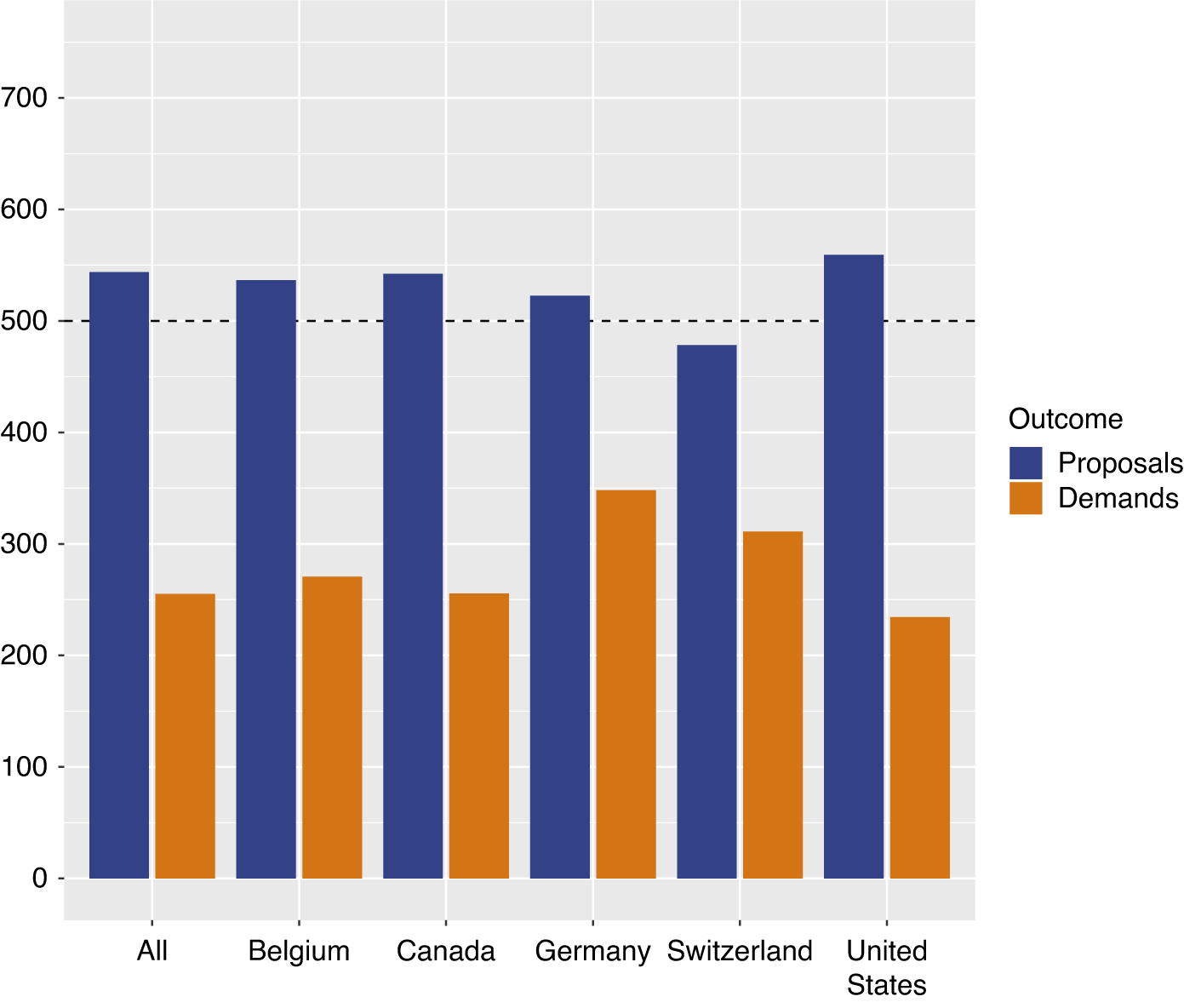

Figure 2 and Table 4 report the effect of our main experimental treatment of interest—being partnered with a co-partisan versus an out-partisan target. Results are reported for the pooled sample (“All”) and for each country separately. The effects are remarkably consistent across country cases and substantively large: politicians strongly favor co-partisan targets, making offers that are 8.5 pp higher, on average, than those made to out-partisans. And similarly, they make substantively lower demands—about 7.5 pp lower—from co-partisans.Footnote 12

Figure 2. Partisanship Treatment Effects by Country

Note: Figure reports effect size estimates of the partisanship treatment used in the study, by country case. Dot estimates are the effect of playing with a co-partisan versus out-partisan target, for proposals (left panel) and demands (right panel). Bars are 95% confidence intervals from two-sided t-tests. Corresponding quantities are reported in Table 4.

Partisanship appears to matter the least in the United States, where local-level politicians who run on party tickets make proposals to out-partisans that are on average 6 pp lower than those they make to co-partisans, and demands that are 6 pp higher. However, these effects are statistically significant and are quite similar to those observed in the other country cases.

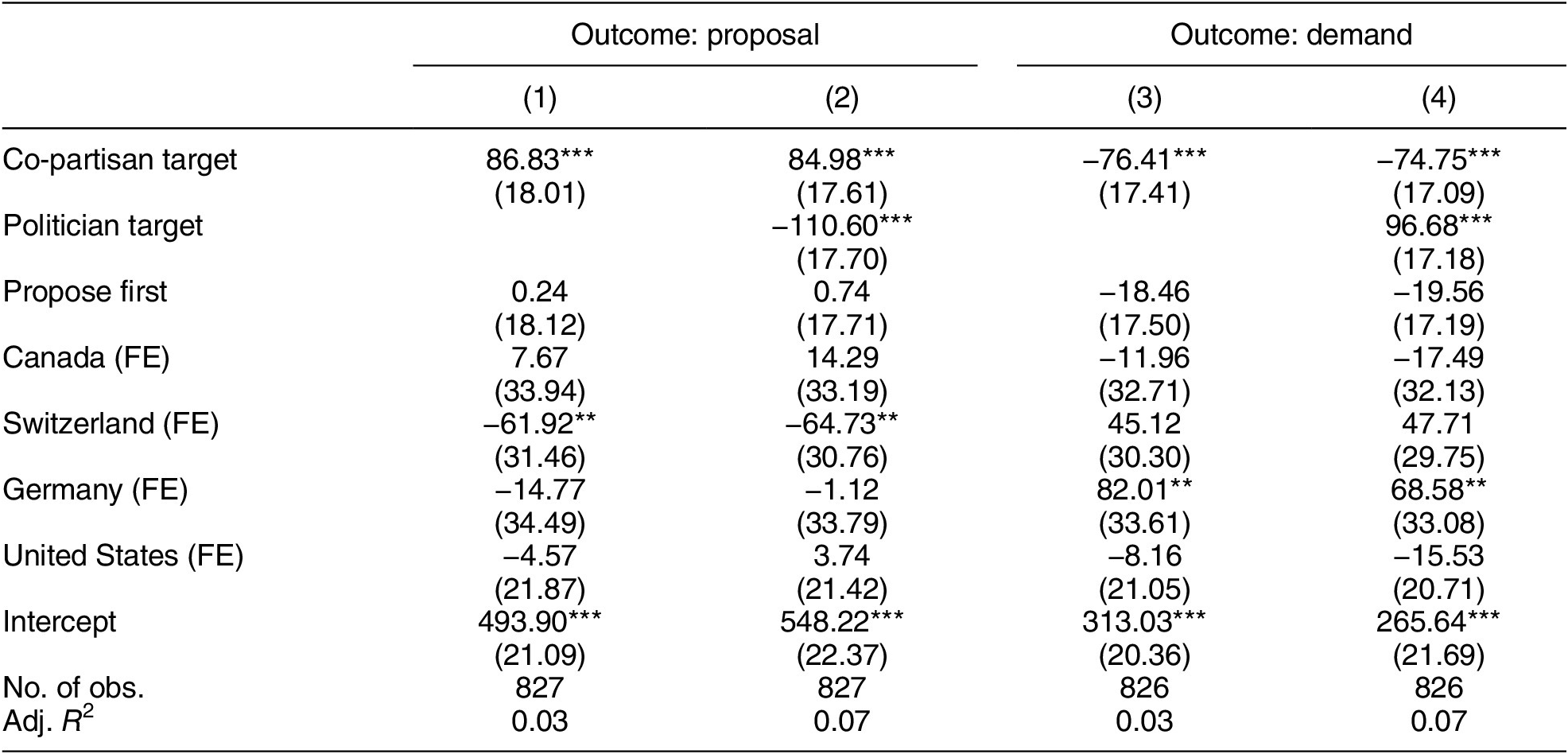

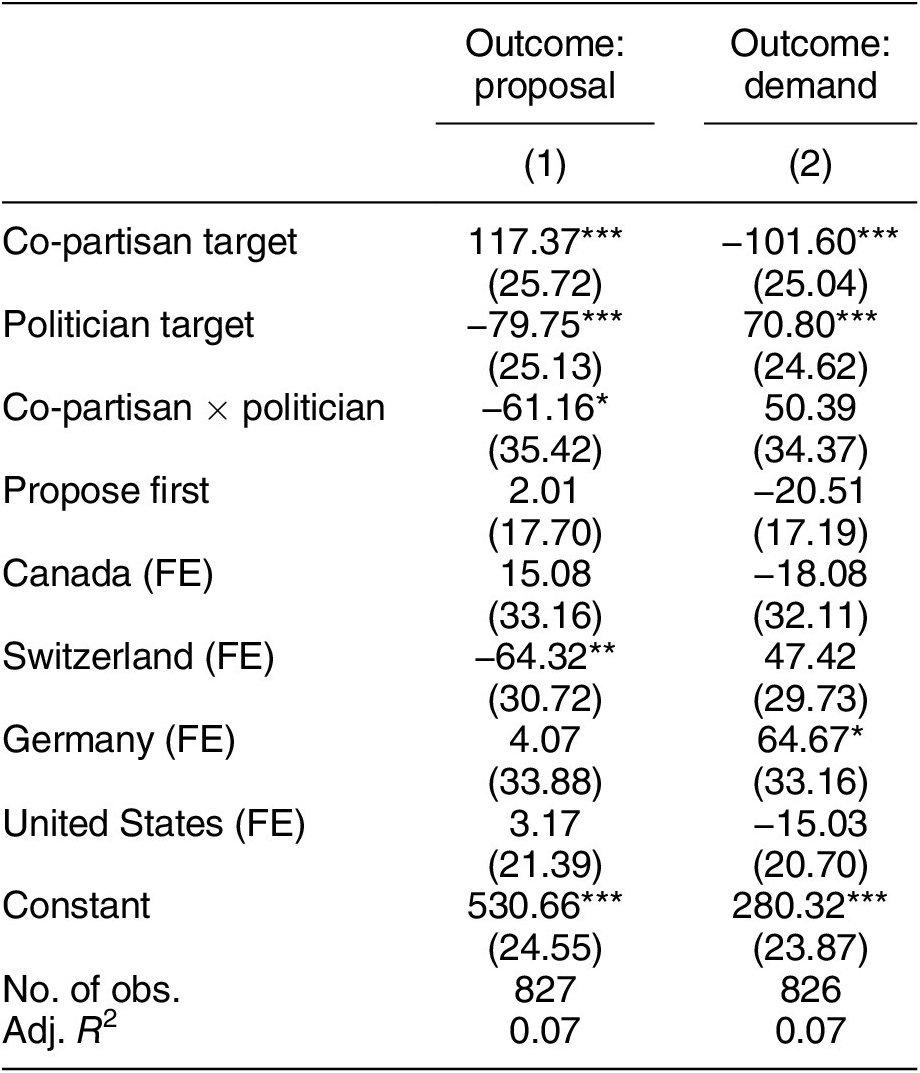

Regression analysis further confirms these effects. Models 1 and 2 in Table 3 report estimation results of linear regression models capturing treatment effects on proposals in the ultimatum game for the pooled sample. Models 3 and 4 report the corresponding estimation results for demands. These models include country fixed effects, and Models 2 and 4 include the cross-cutting politician/citizen treatment for completeness. By-country models estimating these quantities in each of our cases separately are available in the SM. The impact of partisanship is significant, substantively large, comparable to the raw results, and stable across the two specifications for both proposals and demands: co-partisanship results in an 8.5 pp increase in proposals and a 7.5 pp decrease in demands.

Table 3. Main Regression Estimation Results

Note: Estimation is performed on the pooled sample of politicians. Models are linear regressions. Country fixed effects are included, with Belgium as the base rate. Propose first—respondent was asked to make the proposal before stating the lowest acceptance amount. Standard errors reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Interaction: Partisanship Effects Are Conditioned by Counterpart Type

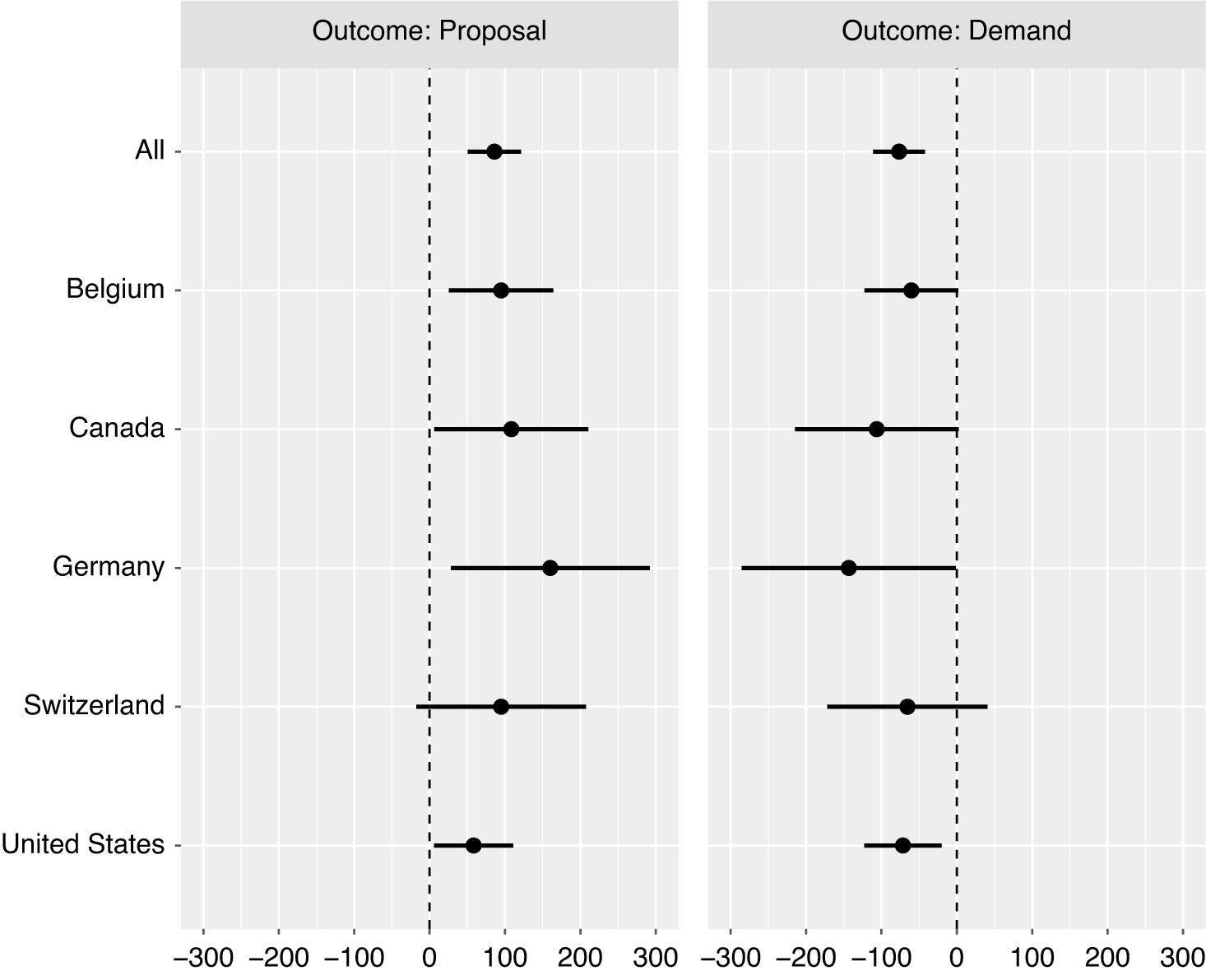

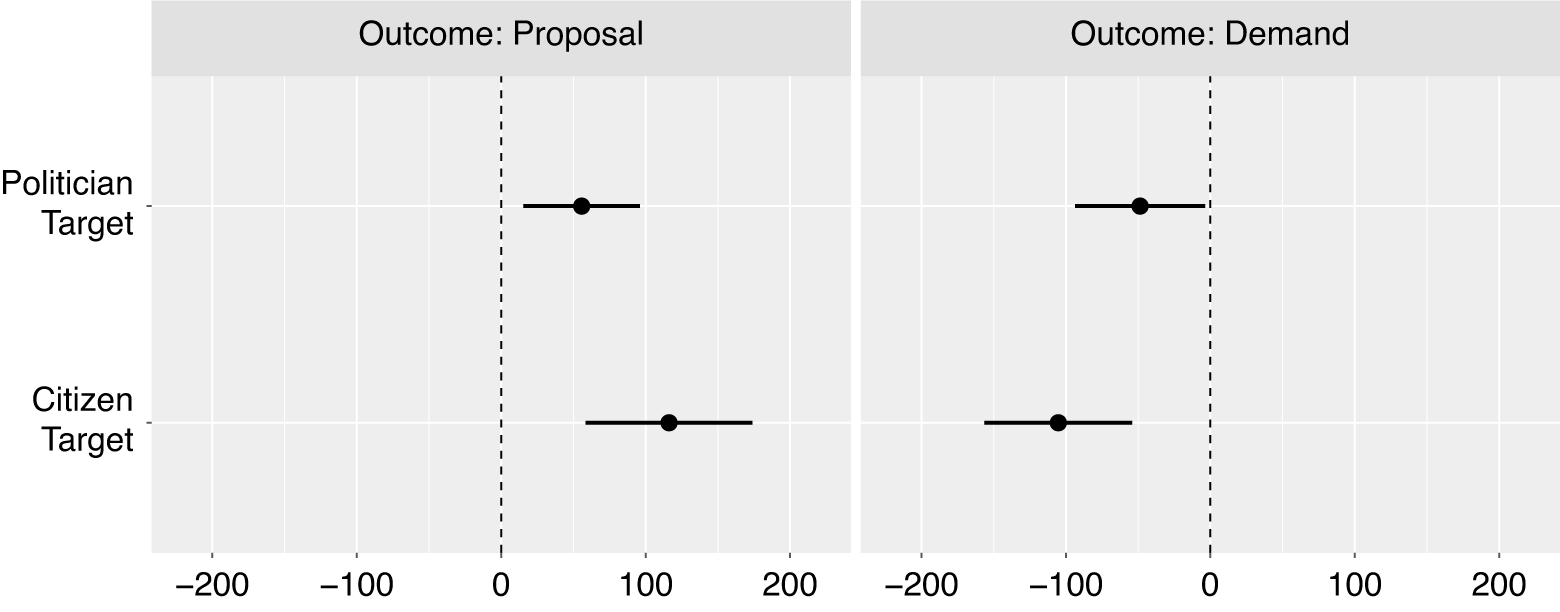

Finally, we examine the expectation that information about partisanship operates differently when politicians bargain with each other relative to when they bargain with citizens. We do so using an interaction analysis estimating whether the effect of co-partisanship on offers and demands is different when the politicians in our study were randomly assigned to a colleague or a citizen as their ultimatum game counterpart. Figure 3 reports our findings. Partisanship has a statistically significant effect on proposals and demands made by politicians in both cases, but the effects are markedly different. When politicians bargain with citizens, partisanship generates a large effect, with co-partisan counterparts receiving proposals that are on average 11 pp higher than those politicians make to out-partisan citizens (mean amounts of 643 Dollars/Francs/Euros vs. 527, respectively). The demands are equally discriminatory, with minimum acceptable offers from co-partisans being about 10 pp lower than those politicians demand from out-partisan citizens (171 vs. 276, respectively). These patterns are separately observed—with varying degrees of statistical significance—in each of our five country cases (see the SM for full details). Importantly, these patterns largely reflect strong in-group favorability: politicians already give over half their allocation to out-partisan citizens, but become hyper-generous toward co-partisans, offering them close to two thirds of the amount. Similarly, they reduce the already-low demand they make to out-partisan citizens. In that sense, politicians mostly discriminate in favor of citizens they identify as supporters, but this discriminatory gap is very large.

Figure 3. Partisanship Treatment Effects by Counterpart Type

Note: Figure reports effect size estimates of the partisanship treatments used in the study (co-partisan vs. out-partisan), for the pooled sample, by whether the target was a politician or a citizen. Dots are the partisanship effect sizes, and bars are the 95% confidence intervals from two-sided t-tests.

In contrast, when politicians engage their colleagues, partisanship still has a statistically significant effect, but it is cut by a full half: the mean effect size of partisanship on proposals and demands is only about 5 pp when the target is a fellow politician. Co-partisan politicians receive on average half of the allocation (505 Dollars/Euros/Francs), whereas rival politicians are offered 449 Dollars/Euros/Francs, or 45% of the amount. A similar pattern is observed with demands (294 vs. 343, respectively). Estimation results for these effects are reported in Table 5. They show an interaction coefficient that is nearing conventional levels of statistical significance for proposals, but not for demands. We note that in terms of the gap between offers and demands they make, the politicians in our sample appear to be better calibrated when engaging out-partisan colleagues than they are when bargaining those from their party, with the former resulting in a difference of about 10 pp between proposals and demands, compared with 21 pp when the target is a co-partisan politicians. Section 8 of the SM reports these results in full and discusses potential interpretations.

Table 4. Partisanship Treatment Effects by Country

Note: Figures reported are mean proposals and demands politicians in the ultimatum game experiment, by co-/out-partisan target treatment. Figures reported are amounts in either Dollars, Euros, or Francs, out of 1,000.

Table 5. Interaction Estimation Results

Note: All models are linear regressions. Propose first—respondent was asked to make the proposal before stating their lowest acceptable offer. Standard errors reported in parentheses. *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Nevertheless, the substantive differences we observe in how partisanship factors in when politicians are faced with different types of counterparts are noteworthy: while partisanship clearly plays an important role in elite bargaining, its effect is substantially reduced compared with how politicians express it when interacting with non-elites. This suggests that a different logic might underlie the way that politicians consider information on the partisan identity of individuals they bargain with: politicians readily and heavily favor co-partisan citizens—perhaps signaling an increased sensitivity to the attitudes of potential supporters over those of foes and a willingness to forego potential personal gain in order to guarantee satisfaction by those whose votes they rely on. One interpretation of the more reserved expression of partisan considerations when facing colleagues is that purely partisan position-taking can be more costly in in-office bargaining, and that different norms of fairness—ones that more closely resemble rational bargaining—shape the expectations of politicians from each other, above and beyond partisan and ideological interests.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we explore how politicians in five different countries engage in a foundational bargaining task. Our results suggest the shared or opposed partisanship of their counterpart systematically affects the strategies they use. This pattern presents with notable consistency across countries, despite the substantial institutional, historical, and political differences between our cases.

On average, politicians’ demands of colleagues do not exceed offers, and more broadly, reflect a high degree of generosity in offers compared with extant findings with non-elites (about 11–14 pp higher than mean offers documented in the literature) while making demands that are on par with non-elite behavior (about 25%–30% of the endowment). However, when the politicians we study are paired with co-partisans, they offer on average 8.5 pp more, and demand 7.5 pp less, compared with when they are pitted against out-partisans. This effect is observable when bargaining with politicians, and is even larger when the negotiation targets are citizens.

We wish to highlight what we believe are three important implications of our findings. First, we think that the consistency of these findings—across widely varying contexts—suggests a certain core element of political expertise. Part of being a practicing politician is to recognize that shared partisanship changes the expectations of how one allocates a scarce resource, as does doing so in a legislative environment versus another, perhaps more public environment. The case for politicians as experts has been downgraded in recent years, with studies showing that politicians systematically fail to accurately grasp public opinion (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Pereira Reference Pereira2021), that they do not pursue policy information when it is available (Loewen, Rubenson, and McAndrews Reference Loewen, Rubenson and McAndrews2020), that they commit the same decision-making mistakes as citizens (Sheffer et al. Reference Sheffer, John Loewen, Walgrave, Soroka and Shaefer2018; Tetlock Reference Tetlock2005), and that they are more generally indistinguishable from non-elites in how they respond to various types of information (Kertzer Reference Kertzer2020). But here, we demonstrate that when engaging in a task central to their roles, they consistently alternate between different strategies when bargaining with counterparts of different partisan identities. Future research could explore what leads politicians to display or develop this specialization, when in so many other aspects of their roles they display what existing research characterizes as a lack of competence or expertise.

Second, we think there are important implications for our understanding of legislative bargaining and the interactions between legislators more generally. To articulate this, suppose that we had seen instead that politicians play a stereotypically rational strategy when pitted against other legislators, in which they offer very little, and demand essentially nothing. Such predictions were long made about ultimatum game behavior (Rubinstein Reference Rubinstein1982), and they are occasionally witnessed empirically under certain conditions (see, e.g., Bornstein and Yaniv Reference Bornstein and Yaniv1998). However, such a strategy does little to generate or sustain cooperation between politicians, as the outcomes of such offers are inequality producing. Imagine a second broad strategy, in which politicians make comparatively low offers to colleagues, all of which are rejected by the recipients. Such a strategy is also unlikely to generate or sustain cooperation between actors, as it depends on high degrees of costly spite from recipients. Instead, what we see is a strategy in which politicians are willing to pay a high price to enforce fairness in interactions with each other, with proposers willing to meet that high price, and then more, but not much more. Such a strategy reflects an abiding concern with fairness and a preference for cooperation. Importantly, this pattern is strongly conditioned by partisanship, suggesting that there is some premium associated with shared partisanship, in keeping with several related findings among citizens in non-ultimatum scenarios (Fowler and Kam Reference Fowler and Kam2007; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015). However, the most important element of the finding is that when bargaining with colleagues, most politicians pursue a strategy which does not destroy wealth (through rejected offers), suggests limited generosity, but still advantages on average the proposer. We do not know whether the operative factor here is norms, internalization of power relations (and meta-perceptions of power relations), or other incentives, but these findings nonetheless help us understand an important feature of legislative institutions: they teach politicians how to work together.

Our investigation is limited to bargaining between politicians (and between them and citizens), yet politicians regularly negotiate with a host of other actors, and these interactions are natural targets for future experimental work. As one notable example, there is an extensive literature exploring how bargaining between politicians and bureaucrats shapes policy outcomes and state institutions (the literature is vast, but see, e.g., Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984; Wildavsky and Caiden Reference Wildavsky and Caiden1988), but we are unaware of studies that recruited senior bureaucrats and politicians to directly evaluate how they negotiate. The absence of bureaucrats in our sample—and the hypothetical targets of bargaining being either politicians or citizens, but not public servants—leaves open the question of what strategies politicians employ when they engage public servants, and whether the latter use their own unique strategies. Future work in this vein could also control for the context of the scenario—e.g., whether the negotiation is taking place at the policy design or implementation stage—and in doing so help identify bargaining scenarios that breed more (or less) trust, cooperation, and compliance in principal-agent relationships, informing existing theories of policy-making and implementation.

Another design element that is not part of the current investigation is a direct comparison of politicians’ behavior with that of their constituents. There is extensive evidence on how non-elites engage bargain in ultimatum scenarios, but none that we are aware of that looks at partisanship effects, or that engages participants with politicians (or other types of elites). Conducting such an investigation is a promising extension of our work that could provide a clearer baseline against which to evaluate the patterns we document among elected officials.

Our work has several other important limitations. First, we are presenting results from games with hypothetical, rather than real stakes. This may impair the construct validity of our findings, although some important work suggest that this should not be a major concern (Cameron Reference Cameron1999; Gillis and Hettler Reference Gillis and Hettler2007; see Smith Reference Smith2005 for a discussion in the context of bargaining). We also focus exclusively on ultimatum-type bargaining, which captures only a subset of the full spectrum of bargaining scenarios that politicians face. Empirically exploring other kinds of legislative bargaining models is necessary for completeness and is a priority for future work.

Second, and related, we have chosen to use a bargaining task, rather than survey politicians on or observe them in a series of real-world scenarios involving cooperation and bargaining. This limits the external validity of our design and the resulting findings. The advantage of using a well-established bargaining protocol, even in the absence of real stakes, is that we can easily compare behavior across individuals, and against well-established empirical regularities in the existing literature. Furthermore, we avoid the endogeneity that would exist in asking politicians to describe real-world bargaining situations or experiences into which they selected. Future extensions of this research could flesh out the implications of these design choices by having politicians consider scenarios which more closely model the kinds of bargains they make in real life, perhaps by focusing on allocations of public funds, controlling for public scrutiny, and varying the reputation and experience of the bargaining counterpart. Another such extension could compare scenarios where the partisan identity of the bargaining counterpart varies in more nuanced ways that often characterize multiparty coalition-based systems; for example, examining differences between negotiations that involve partisans who are both members of a governing coalition, compared with partisans who do not share governing goals, or differences in bargaining between partisans who compete over the same pool of votes versus those who have distinct electoral constituencies.

Third, our design is well positioned to identify the partisanship effect we document, but we cannot definitively adjudicate between competing explanations for it. For example, politicians could be more or less generous toward co- and out-partisans because of factors not directly related to politics, such as perceptions of deservingness based on social status or income, or inferences on personality traits that imply trustworthiness and cooperative disposition, among other possible alternatives. Future work that assesses the relative impact of different determinants of politicians’ bargaining choices is certainly needed, and is a natural extension of this study. Another useful line of future work could more closely examine the assumptions politicians make on what their bargaining targets know about them, and whether this impacts their behavior. While the phrasing of the vignette used in this study entails that the respondents’ partisanship is not known to the target, we do not know if participants assumed otherwise, leaving this as an open question in our work.

The current study is particularly limited in its ability to explain differences in results between the country cases in our sample. While the overall patterns we document are consistent across our cases, we still observe noteworthy differences. For example, when facing co-partisans, politicians in Canada make the second-highest mean proposals and pose by far the lowest demands compared with politicians in the rest of the countries in our sample. Out-partisans receive an especially stingy treatment by German and Swiss politicians (mean offers of 448 and 428, respectively, and mean demands of 422 and 345), and American and Belgian politicians show the smallest degree of partisan discrimination in offers (a 5.8 pp gap in offers in the United States) and demands (a 5 pp difference in demands in Belgium). These differences in how politicians engage different partisans can be attributed to a host of potential system-level factors, such as the types of constituents that politicians represent or expect to interact with (e.g., systems where re-nomination—and subsequently re-election—is based on a broad constituency of citizens vs. those where it is more strongly dependent on party members and leaders, or systems with a district-based vs. at-large electorate). Explaining such variation is theoretically important and exceeds the scope of the current paper. It could be undertaken, for example, by conducting simulated laboratory experiments that control for various institutional features.

Finally, future replications of our work would be useful, and, in line with the previous point, especially those that consider extensions and replications in other country cases. The countries we examined are all developed and stable liberal democracies. Whether the patterns we see appear when tested with politicians in more authoritarian systems, or in emerging democracies, and certainly in countries where the electoral and partisan environments are different from those that characterize our cases, is of crucial importance for the comparative study of legislative behavior, and for the study of elite bargaining in particular.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001459.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the American Political Science Review Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MKWIHN.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Arno Jansen, Karolin Soontjens, Julie Sevenans, Kirsten Van Camp, Pauline Ketelaars, Yves Dejaeghere, John McAndrews, Matthew Ayling, Blake Lee-Whiting, Jonah Goldberg, and Roosmarijn De Geus for their contributions to this project. We also wish to thank the Editor and four anonymous reviewers for their thorough and helpful feedback. For invaluable discussion and comments, we wish to thank Dominik Duell and Brad LeVeck; participants of the mini conference on Political Institutions and Elite Behavior: Experimental Approaches in the 2019 Midwest Political Science Association conference; the 2020 American Political Science Association Conference; the 27th EGAP Conference; the 2020 Nordic Workshop on Political Behavior; and the 2022 Reading University research seminar.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was supported by the following grants: Flanders-Belgium: Stefaan Walgrave (FWO, grant number G012517N); Wallonia and Brussels-Belgium: Jean-Benoit Pilet and Nathalie Brack (FNRS, grant number T.0182.18); Canada: Peter John Loewen and Lior Sheffer (supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant and by the Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science at the University of Toronto); Germany: Christian Breunig and Stefanie Bailer (funded by AFF 2018 at the University of Konstanz); Netherlands: Rens Vliegenthart and Toni van der Meer; and Switzerland: Frédéric Varone and Luzia Helfer (SNSF, grant number 100017_172559).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the relevant ethics boards. In Belgium, we first obtained ethical approval from the Ethische Adviescommisse Sociale en Humane Wetenschappen of the University of Antwerp (Flanders, Belgium) on February, 10, 2017, and then ethical clearance from the Comission éthique de la Faculté de Philosophie et sciences sociales de l’ULB (Wallonia) in March 2018. In Canada, we obtained ethical approval from the University of Toronto’s Social Sciences, Humanities & Education REB on November 27, 2018. In Switzerland, we obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Commission of the Geneva School of Social Sciences (University of Geneva) on April 16, 2018. In Germany, the Ethics Committee (IRB) of the University of Konstanz judged that approval by the IRB or any regulatory body was not required for this project (but note that the university more generally enforces the proper adherence to ethics guidelines).

The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.