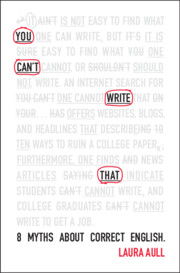

It is easy to find what you can’t, or shouldn’t, write. An internet search for you can’t write that … will lead to “grammar mistakes that make you look dumb” and news articles saying students can’t write and college graduates can’t write to get a job.1

My own students, whether brand new undergraduates or graduate students training to be professors, have all heard these messages. They learned them by having their writing corrected continuously. “Correct English was whatever my English teacher deemed correct and had written in red all over my writing assignments,” said a college student this fall. “I learned that the language we used in school, particularly for written tasks, was the most ideal for all situations,” noted another. They describe dreading timed writing tests, following rules such as “don’t use I,” and learning to avoid words they use with family and friends, like ain’t.2

Most reveal that in the process they also learned they are bad writers, or not writers at all. When I tell them they write every day, crafting text messages, posting ideas and reactions, and sending emails, they say that doesn’t count. “But that’s not real writing,” one said to me last year. “Anyone can do it.” What I am getting at is that none of these messages actually mean people can’t write. They mean writers aren’t always using one kind of writing, the kind expected in schools and tests. That’s why we understand the blog title “How to write a college application essay when you can’t write” – because it is common to use terms like “write” and “writing” to refer only to what is so-called correct writing.3

As you can tell, I am using correct writing to refer to the formal, written English required in school, particularly in and after secondary education. By then, most students are expected to write formal sentences and paragraphs, and they are taught and tested according to only a small part of the writing they do every day. Accordingly, there are some things I don’t mean by correct writing. I don’t mean literary or fiction writing. Though admired, literary writing is not how most people have to prove their learning or gain employment, and it has more flexible norms than the norms we will see emerge in myth 1. I also don’t mean all standardized English, since people can use standardized English and any other English dialect more and less formally, in speech or writing. Correct writing does vary across authors and audiences (e.g., general or specialist), genres (articles, proposals, essays), and fields (engineering, history); even so, correct writing entails some important overall ideas and language patterns we will see throughout this book.

i.1 The Writing We Actually Do

The actual writing most people do goes far beyond correct writing. In a single day, it is common to write a text message in one moment, an email in another, and a paper or report after that. Even these won’t all be the same – your text to your friend may be more informal than one to your coworker, for instance. Table i.1 shows a continuum of written English, beginning with informal, interpersonal, and personal texting and ending in formal, informational, and impersonal published writing. Remarkably, this whole diverse, dynamic continuum is possible in written English.

Table i.1 Writing continuum

i.2 Language Regulation Mode

This continuum is not what most of us learn, at least not explicitly. In school, we learn about what we can’t or shouldn’t write, according to the far right of the continuum only. We don’t learn what we can and do write – or might write in the future – across the full continuum.

In other words, most people learn in language regulation mode, which means they actually learn less about language. They learn only to regulate, and be regulated by, correct writing rules and errors, rather than to understand a range of possible writing choices. The sociolinguist Geneva Smitherman calls this “linguistic miseducation,” which is when “teachers be obsessed wit teaching ‘correct’ grammar, spelling and pronunciation rather than teaching students what language is and allows human beings to do.”

In this quote, Smitherman describes and defies the limits of language regulation mode. She follows some norms on the far right of the continuum, including spelling choices dating back to Chancery English, as we will see in myth 1. She also follows some spelling and grammar norms used beyond the far right of the continuum, including wit and the continuous be verb (be obsessed) used in informal and formal Black English.

But many of us have learned only language regulation, rather than learning to understand the power of a full continuum of writing options. In the process, we’ve learned several myths about writing.

In particular, we’ve learned eight writing myths addressed in this book:

1. Only one kind of writing is correct.

2. Schools must regulate writing.

3. Writing indicates natural intelligence.

4. Tests must regulate writing.

5. Most students can’t write.

6. Writing should be mastered in secondary school.

7. College writing ensures professional success.

8. New technology threatens writing.

Some of these myths – for example, the first three – have been with us since English came to schools and tests 150 years ago, and all of them fuel one another. It is hard to even recognize that they are myths. Individuals such as Geneva Smitherman may see past them, but her view is the exception, not the rule.

Here’s one way to think about this, if you are a sighted person: These myths are like a pair of shutter glasses we began wearing very early, before our eyes were trained without them. The myths don’t give us a true (or unadjusted) view of writing, but that view is real – it is our perceived reality.4

Figure i.1 Myths glasses

We take the myths for granted, like glasses (bear with me) we never realized we put on. We trust the view, even when key facts don’t make sense, such as the fact correct writing is not useful across the continuum in Table i.1 but is the writing considered correct. Or the fact that we say every student should have a chance, but we only give correct writers credit and opportunity. Or the fact that tests call only the right side of the continuum “clear,” as though informal writing cannot be understood. Through the myth glasses, we get used to these contradictions. We don’t know how to see writing, or talk about it, any other way.

All the while, schools and tests automatically reward people with the most exposure to the right side of the continuum – most often middle- and upper-class families, white people, children of parents who went to college. As this goes on, writing myths limit everyone’s knowledge of the actual writing people do.

If we are looking through the myth glasses, none of this appears to be a problem, or at least not a solvable one. It is impossible to use contrary evidence (such as writing variation) because that very evidence is treated as irrelevant, or as lowering standards. Put another way: Even when we see limitations and contradictions, we are likely to be told the problem is us, not the glasses.

So it is that with writing myths, we judge more, and we learn less.

i.3 What Should We Do Instead?

To judge less, and learn more, we need language exploration instead. We need to explore writing patterns across the continuum, instead of regulating one part of the continuum. To illustrate, we’ll look at two examples my students often mention: first-person pronouns like I, and the word ain’t.

In language regulation mode, many of us learn “don’t use I” and “don’t use ain’t.” In language exploration mode, instead, we learn how people tend to use first person pronouns and ain’t.

For example: First-person pronouns are used across the writing continuum, but differently. On the informal, interpersonal, personal side of the continuum, writers tend to use first-person pronouns in “text external” ways, meaning they emphasize personal experiences and reactions in the “real world.” In a recent tweet I saw, for instance, a new user introduced themselves using the first person my to emphasize personal experience, and informal punctuation and spelling norms to convey excitement and familiarity: english is not my first language !!.

On the formal, informational, impersonal side of the continuum, writers tend to use first-person pronouns in “text internal” ways, meaning they focus on information in the unfolding text or research. In this book, for example, I include text-internal first person and formal punctuation and spelling norms, like I just did: In this book, for instance, I include text-internal first person.

Ain’t, on the other hand, is rarely used on the right side of the continuum. Historically maligned in upperclass conversation, ain’t has been viewed with the myth glasses firmly on. As we will see in myth 1, early usage guides put ain’t on the left side of the continuum and told writers it was always incorrect, even though it is grammatically possible and meaningful in English, used by writers of English, and very like the contraction won’t. Today, ain’t is regularly used on the left side of the continuum, often with negation and first- and second-person pronouns – for instance, in expressions like if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, and usage such as ain’t no stopping me now.5

What I’ve done here is pay attention to patterns in how people use written English, across the continuum. To say more about this, I’ll address why we should do language exploration now, and why we shouldn’t keep doing what we are doing, which is prioritizing correct writing only.

i.4 Why Language Exploration Mode?

Today, the gates to universities and other schools are much more open than they were 150 years ago, when myth 1 emerged. Black, brown, female, neurodivergent, and working-class students, people not welcome until relatively recently, pass through the gates. Even as more diverse writers are welcome, however, more diverse writing is not.

We have similar writing gatekeepers, no matter the wider gates, in other words. More than a century ago, we had the monocled eighteenth-century grammarian Lindley Murray (more on him later); today, we have the style guide Eats, Shoots & Leaves saying we live in a world where “Everywhere one looks, there are signs of ignorance and indifference.” At universities, we had Harvard’s Charles Eliot in the 1870s, ensuring entrance exams in all subjects were checked for correct writing; today, we have standardized writing exam scores used in college admissions.

Writing gatekeepers demand correct writing before college; then they follow everyone inside, hovering about in writing courses and papers and playing a decisive role in college graduation and job applications. Correct writing gratekeepers have numerous tools to help them, from standardized writing exams to cover letter advice. They have trusted institutions, which give up on people who don’t use correct writing.6

And yet we have had an alternative all along.

Patterns across the writing continuum are already part of our language knowledge. At minimum, we have unconsciously been paying attention to language patterns all our lives: in the womb, to sound patterns; as toddlers, to grammatical patterns; as teens, to texting punctuation and school-essay formats.

These patterns created a foundation for understanding and producing English. When we started writing English, for instance, we didn’t memorize and regurgitate what we read. We relied on patterns, big and small:

happy birthday, not *merry birthday

make a decision (or: make the right decision or make difficult decisions), not *decision make a right

capitals as emphasis (AMAZING!!!) in informal text messages, but capitals at the start of a sentence in a formal chapter.

These are example patterns we recognize, consciously or subconsciously. They appear at all levels of writing, from phrase (happy birthday) to genre (text message or book chapter) to register (informal or formal). Sometimes, these patterns are obvious, and sometimes, they are subtle. But we can explore and learn about them if we know what to look for.

Since most of us learned by language regulation – instead of language exploration – many students, educators, and employers do not have conscious knowledge of writing patterns. Unfortunately, subconscious knowledge is less usable than conscious knowledge, and it makes it much easier to keep the myth glasses on.

i.5 But Shouldn’t We Still Prioritize Correct Writing?

Most of us have learned that we have to prioritize correct writing in school, in the name of access to opportunity, or based on the idea that the alternative means having no standards at all. But language exploration is not the same as anything goes. Language exploration means we explore what people can and do write rather than limiting ourselves to what they can’t or shouldn’t write.

Expanding our understanding of writing makes us more knowledgeable about what is already true. Diverse writing is correct in different contexts, already, even if it is not understood or studied as correct writing.

Furthermore, we haven’t tried the alternative. We have never had a widespread English schooling model that explores diverse writing patterns for native and early learners of English. We’ve only ever had language regulation of one part of the continuum. This why throughout the myth chapters, you will see government policies, school reports, and news headlines that reinforce the myths, as they have for over a century.

On the one hand, this repeition reminds us not to take correct writing too seriously, seeing as we could go back to the nineteenth century and tell writing gatekeepers that written English did survive, and people kept right on complaining about it. It reminds us that some doomsayers will always believe that writing is going to hell on a Ferris wheel, no matter what this book says.

On the other hand, longevity doesn’t make writing myths harmless – quite the contrary. Writing myths, benefit some people and not others, and their consequences are more dire for some than others. Some of the writing myths have been specifically used to erase Indigenous languages, to label Black and brown people lazy or dumb, and to pronounce women less capable of college. Many groups and individuals who have not used the far right of the continuum at the right moment – even as they write in many compelling and successful ways – have faced consequences that correct writers, perceived as disciplined and intelligent, have not.

Worse: We are still living with the myth glasses on. Writing myths are not a thing of the past. I still encounter them all the time, and I use we in this book because, like so many, I learned to write, and evaluate others’ writing, with the myth glasses on.

The good news is that many of us are seeking better answers. Better answers for the student told they cannot write, and the employer who won’t hire someone who uses ain’t or a comma splice. Better answers to the claim that people don’t write anymore, and the fear that English writing is doomed.

Regardless of prior training, this book is written for the many of us in this situation – educators, students, employers, scholars, parents – who regularly encounter English writing and writers, and want better ways to do so. I have accordingly tried to make this book accessible for a range of readers, by noting references at the end (organized by myth chapter and section) and avoiding the dense syntax customary on the far right of the continuum. I also focus on how historic, educational, and linguistic details come together in myths, though many of these details have their own stories beyond the scope of this book.

i.6 Chapter Outline

The book addresses eight writing myths in eight myth chapters. Each myth chapter is organized in three parts:

Context: how we got the myth

∘ An origin story

Consequences: why the myth matters

∘ Why we should care

Closer to the truth: how we move beyond the myth

∘ Exploring language patterns

The myths are summarized briefly below according to their opening scenes, leading characters, and key details. In the conclusion, I talk more about what to do next.

Myth 1 You can’t write that

Or, Only one kind of writing is correct

Opening scenes: fifteenth-century spelling standardization

Leading characters: Chancery spelling, dictionaries, usage guides

This myth starts with early spelling standardization and continues with early usage guides. Its consequences include making enemies of formal and informal writing, and making people think correct writing means one thing – and means a capable and good person. Closer to the truth? Terrible writers can be good people, good writers can be terrible people, and all shared writing includes some fundamental similarities, and some differences. Formal writing fancies nouns more than verbs, for instance, and it likes informational subjects. Informal writing has more equal affection for nouns, verbs, pronouns, and adverbs, and it favors interpersonal subjects.

Myth 2 You can’t write that in school

Or, Schools must regulate writing

Opening scenes: eighteenth-century schools

Leading characters: language policies, English literature, school curricula

This myth starts as English shifts to schools (away from home instruction), and schools shift to English (away from classical languages). Its consequences include making English regulation common and desirable, and making language variation a threat. Diverse ways of writing persist, but they aren’t studied in school. Closer to the truth is that language diversity and language knowledge are human rights, but school writing focuses only on a narrow part of the writing continuum.

Myth 3 You can’t write that and be smart

Or, Writing indicates natural intelligence

Opening scenes: mid nineteenth-century schools and tests

Leading characters: phrenology, IQ tests, writing scales

Myth 3 starts as correct writing becomes a tool for ranking students and innate ability. Consequences include limiting how we understand intelligence, trusting tests instead of teachers, and trusting test results without understanding tests. Closer to the truth is that uniform tests and scales are not fair, and they tell us a two-dimensional story about writing. Closer to the truth is that writing is three-dimensional – social, diverse, and unnatural – and on a continuum rather than a scale.

Myth 4 You can’t write that on the test

Or, Tests must regulate writing

Opening scenes: late nineteenth-century expansion of higher education

Leading characters: college entrance examinations, standardized exam tasks

This myth starts as spoken and interactive exams end and written English exams begin. Its consequences include that every exam becomes an English exam, as correct writing gets evaluated in everything from history to geography to English composition exams. Its consequences also include that exam culture overshadows learning culture, and we prioritize efficiency and sameness over variation. Closer to the truth is that standardized test scores measure socioeconomic status, tests only test what is on tests, and exam tasks solicit a narrow continuum of writing.

Myth 5 Chances are, you can’t write

Or, Most students can’t write

Opening scenes: twentieth-century news

Leading characters: writing exam reports, standardized test results, news headlines, standardized exam writing

This myth begins when early college exam graders say students cannot write, then really emerges when headlines begin reporting standardized test results. Consequences include that test results define writing and writing failure, and we accept test-based claims and criteria. We make limited standards the same thing as excellent standards, and we think about writing in terms of control rather than practice. Closer to the truth is that early exam reports were sometimes inaccurate, errors are changing but not increasing, and tests and scoring criteria change. Standardized exam writing is limited, but most students write across a broad writing continuum when they are not writing standardized exams.

Myth 6 You can’t write if you didn’t write well in high school

Or, Writing should be mastered in secondary school

Opening scenes: twentieth-century secondary schools

Leading characters: standardized tests, composition courses, news headlines, secondary writing, college writing

Myth 6 starts at the same time as myth 5, but in this one, we learn that correct writing should be mastered by secondary school. As a result, this myth limits how we think about writing development, including who we think is responsible for it. Other consequences include that we ignore important differences between secondary and college writing, like the fact secondary writing tasks tend to be brief, persuasive, and rigidly organized, while college writing tends to be multistep, explanatory, and organized according to topic and genre. Closer to the truth is that writing development is a spiral rather than a line: It is ongoing, and not everything comes together at once. Also closer to the truth is that we can support the move from secondary to college writing by exploring writing continuum patterns.

Myth 7 You can’t get a job if you didn’t write in college

Or, College writing ensures professional success

Opening scenes: twentieth-century colleges and workplaces

Leading characters: magazines, university presidents, college papers, workplace email

This myth begins when popular magazines and university presidents start selling the idea that college education will lead to economic mobility. Consequences include that workplace writing is a “sink-or-swim” process for many new workers, while college assignments and courses are often limited to correct writing only. Closer to the truth is that college and workplace writing are different worlds, with different goals and tasks. Yet we can build metacognitive bridges between writing worlds, by exploring writing patterns within and across them.

Myth 8 You can’t write that because internet

Or, New technology threatens writing

Opening scenes: late twentieth-century headlines

Leading characters: television, digital writing, news headlines, formal writing

The final myth brings us full circle to myth 1, because it keeps limiting correct writing. It puts correct writing at odds with informal digital writing, even when correct writing is critiqued for being stodgy. We get the idea that correct writing is controlled, whereas informal digital writing is careless, and we limit who reads correct writing and what writing is studied in school. Closer to the truth is that if you are alarmed by something – say, text message slang – you will notice it more, even if most written English is neither changing nor fundamentally different. Informal writing is not the same thing as careless writing, and it is both similar to and different from formal writing on the writing continuum.

Conclusion: Writing continuum, language exploration

The conclusion looks back over the myths to consider where we’ve come from and where we can go next. We already have language patterns, subconscious knowledge, and interest in language to help us. With awareness of timeworn myths, we can move to a new metaphor for writing: a continuum with shared purposes, as well as distinct patterns. A continuum enables us to recognize the range of informal and formal, personal and impersonal, interpersonal and informational writing our world demands. It allows us to see that all these types of written English are systematic, meaningful, similar, and distinct. It allows us to approach a full range of written English as fodder for knowledge and exploration.