Like Hannah Gadsby, Dave Chappelle understands the art of quitting. Chappelle famously walked away from a $50 million deal with Comedy Central when he quit during production of the third season of Chappelle’s Show in 2005. In interviews he has pointed to a white crew member’s reaction to a particular sketch when explaining his reasons for leaving the critically acclaimed show, which was known for its boundary-pushing treatment of race. In a 2020 episode of My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman, Chappelle tells Letterman that in the sketch, he played a pixie “dressed in blackface, who would pop up anytime a person felt the pains of racism” (in Letterman Reference Letterman2020; see also Oprah.com 2006). While filming this sketch, Chappelle explains, he heard the white crew member laugh and felt the crew member was laughing at the blackface, rather than Chappelle’s use of racialized humor to make a critical point. Chappelle then felt ashamed of the way he was portraying his own race. Chappelle’s stated reason for quitting his hit show is similar to Gadsby’s rationale for quitting comedy in Nanette (2017; 2018 on Netflix), the show in which she infamously “broke comedy”: having built a career on self-deprecating humor, Gadsby came to feel she was deprecating her actual self and wanted to stop. In the show, she linked her feeling of humiliation to her marginality as a gender-nonconforming lesbian from rural Tasmania (see Balkin Reference Balkin2020:74). Footnote 1 Both comedians were uncomfortable with what they were inviting audiences to laugh at when they performed in ways that could be perceived as reinforcing their marginalization and oppression.

Figure 1. Hannah Gadsby in Nanette (2018), directed by Jon Olb and Madeleine Perry and filmed at Sydney Opera House for Netflix. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)

In his 2021 Netflix special The Closer, Chappelle quits again, but differently. This performance of quitting responds to and often inverts the politics and structure of Nanette. The Closer is the last of six Chappelle comedy specials released by Netflix between 2017 and 2021. It follows Sticks and Stones (2019), which asserts a thick skin — the opposite of politically correct, oversensitive “snowflakes” — with its title. Nanette is an unnamed intertext in both Sticks and Stones and The Closer, an emblem of the “cancel culture” Chappelle rails against in these shows. Like Nanette, The Closer challenges audiences to consider what is and isn’t funny: Gadsby’s challenge takes the form of withholding tension-relieving punchlines and, like Gadsby, Chappelle is “far more comfortable than most of his peers in going long stretches without jokes” (Zinoman Reference Zinoman2021). But whereas Gadsby’s performance of quitting in Nanette strives to show how comedy can harm marginalized performers, in The Closer Chappelle invites cancellation by leaning into the persona of a homophobic, transphobic comedian, making a platform out of the accusations leveled at him following the release of Sticks and Stones. But he does not maintain this persona consistently: toward the end of the show, he tells a serious story about transgender comedian Daphne Dorman, who defended Chappelle and whose death by suicide he attributes to hounding by Twitter activists. At the end of the show Chappelle claims he is “done” telling jokes about LGBTQ people “until we are both sure that we are laughing together.” Footnote 2 Here too, the structure of The Closer echoes that of Nanette with its serious ending and disavowal of a brand of humor for which Chappelle has become well known.

Cancel culture is “the action or practice of publicly boycotting, ostracizing, or withdrawing support from a person, institution, etc., thought to be promoting culturally unacceptable ideas.” Footnote 3 It “most often starts with a social media campaign […] and can end with that person losing their job or reputation” (Button Reference Button2021). Critics of cancel culture often “sit to the political right, describing it as a kind of political correctness, or identity politics gone mad” (Bouvier and Machin Reference Bouvier and Machin2021:308). Indeed, cancel culture is often said to be an invention of the right designed to deflect criticism, though the contemporary usage of “cancel” to denote boycotting celebrities deemed politically problematic emerged circa 2014 on Black Twitter (Romano Reference Romano2021; Holloway Reference Holloway2021). Cancel culture has also been criticized by some comedians, not all of them right-wing, on the grounds that it limits what they can say, making comedy “safe” and “boring” (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2021). Chappelle’s invitation to cancel him in The Closer worked, without causing Netflix to remove it from the streaming platform: amidst a slew of tweets and media articles denouncing The Closer, transgender Netflix employees staged a walkout; and Jaclyn Moore, the showrunner for the Netflix series Dear White People (2017–21), announced on Twitter that she would no longer work with the network due to its support of Chappelle’s transphobic content ( Jaclyn Moore Reference Moore2021; NBC News 2021). Footnote 4 Chappelle subsequently noted in a video posted to Instagram that his documentary film, Untitled (2021), had been disinvited from film festivals; in the video he invited the audience to decide whether he had been cancelled. In the same video he set three “conditions” for meeting with trans people who are offended by The Closer: they must watch the whole special, they must meet at a place and time of Chappelle’s choosing, and they must “admit that Hannah Gadsby is not funny” (Chappelle Reference Chappelle2021). Meanwhile, The Closer scored a 96% audience approval rating on popular review site Rotten Tomatoes, emphasizing a gap between “woke critics” and average viewers (Hammer Reference Hammer2021) and the fact that cancellation is excellent publicity. Footnote 5

Figure 2. Dave Chappelle in The Closer (2021), directed by Stan Lathan and filmed at The Fillmore, Detroit, for Netflix. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)

Much of the public debate about The Closer was about whether speech is free and whether comedy has real-world effects. Chappelle has contributed to the terms of this debate with the title of Sticks and Stones and with familiar rhetoric about what comedians are “allowed” to say. Netflix co–chief executive Ted Sarandos reinforced these terms when he defended Chappelle, arguing in a leaked memo that “content on screen doesn’t directly translate to real-world harm” (Donnelly 2012b). Sarandos later apologized in an interview with Variety, noting, “Of course storytelling has real impact in the real world” (Donnelly Reference Donnelly2021b). The terms of the debate obscure the conventions of persona and comic license that have governed comedians’ speech since the mid-20th century. Comic license “is the product of negotiation: between performer and audience, between communicating intention and having that intention realized” (Aarons and Mierowsky Reference Aarons and Mierowsky2017:166). But while some comedians including Chappelle and Chris Rock invoke the dialogic nature of comic license as superior to and more ethical than cancel culture, its reliance on liveness makes comic license an incomplete and even misleading framework for understanding stand-up in the era of the Netflix comedy special. Chappelle in particular addresses his online critics more than his live audience in his most recent specials, suggesting The Closer must be understood as a performance inseparable from its extended mediatized context. Analyzing it in dialogue with Nanette and other intertexts including social media posts, the secret epilogue to Sticks and Stones, and Chappelle’s favorite book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (Reference Douglass1845), reveals a series of bad-faith speech acts that have had real impacts in the real world. Seen in this light, the internal inconsistencies in Chappelle’s rhetoric do not undermine his project so much as constitute it.

Persona and Truth-Telling

At the start of a show, a stand-up comedian “establishes his or her comic persona, discussing personal background, lifestyle, and some attitudes and beliefs” (Mintz Reference Mintz1985:71). This convention has been foundational to stand-up since the mid-20th century, when the genre shifted from “impersonal joke-telling” to a new style that was “far more personal and improvisational” (Oppliger and Shouse Reference Oppliger and Shouse2020:12). In the wake of this shift, Eric Shouse argues, “almost every aspect of the stand-up performance has evolved to give the impression of truthfulness” (Shouse Reference Shouse, Patrice and Shouse2020:33). Some comedians understand this genre convention as something like an ethical imperative, feeling “that a comic’s persona should accurately reflect his or her essential personhood” (31), while others distance persona from performer to varying degrees. For those in the former category, performing stand-up might be understood to overlap with the practice of “speaking my truth,” a popular phrase emphasizing the authentic lived experience of the speaker. Indeed, Gadsby invokes the idea of speaking her truth at the end of Nanette, when she says that she “must quit comedy. Because the only way I can tell my truth and put tension in the room is with anger.” Footnote 6 Gadsby rejects the stand-up convention of changing stories from her life to conform to the affective structure of jokes. A good example of this convention is Richard Pryor’s differing accounts of the time he set himself on fire. While in Pryor’s 1995 autobiography he describes the event as a suicide attempt, in his 1982 show Live on the Sunset Strip he framed it as an accidental explosion while freebasing cocaine (42). Pryor’s account of how, as a comedian, he would “take the emotion to a peak and then level it off…with a nice laugh” (in Watkins [Reference Watkins1994] 1999:544) likewise resonates with Gadsby’s description of the comedian’s role in Nanette: “I make you all feel tense, and then I make you laugh, and you’re like, ‘Thanks for that. I was feeling a bit tense.’” But, Gadsby notes, “in order to balance the tension in the room,” she cannot tell her own traumatic story “as it actually happened.”

The traumatic story Gadsby refers to is one of the most famous bits in Nanette, which initially appears to be an old standby from her comedy career: the time she was nearly beaten up for flirting with a woman at a bus stop in Tasmania. The woman’s boyfriend turned up and started shoving Gadsby, calling her a “fucking faggot” and telling her to “keep away from my girlfriend, you fucking freak!” The woman intervened by telling her boyfriend Gadsby was a woman. The man apologized and backed off, saying, “I don’t hit women. Sorry, I got confused, I thought you were a fucking faggot, trying to crack onto my girlfriend.” Footnote 7 The joke is about the man’s ignorance, first in mistaking Gadsby for a gay man who was nonetheless coming onto his girlfriend, and then in assuming that a woman could not possibly be hitting on his girlfriend. Later in the show, Gadsby returns to this story and reveals that in real life it had a different ending. The man returned to the bus stop after he realized Gadsby was hitting on his girlfriend; he called her a “lady faggot,” added, “I’m allowed to beat the shit out of youse,” and did so. Gadsby’s point in restoring the real ending is that comedy is not structurally built for it: a joke, she explains, creates and then releases tension when the punchline makes the audience laugh, but the ending to this story is not funny. Footnote 8 Much of Nanette is an exercise in building tension and then not releasing it; the show contains long humorless stretches as a result. The aim is to make audiences think about what they are laughing at and how comedy works by withholding that release.

The Closer contains an inversion of the bus stop story in which Chappelle casts himself as a man who beat up a butch lesbian after misgendering her. I believe Chappelle’s bit responds to Gadsby’s, though he does not mention her:

Another time, about six years ago, there was a lesbian woman that tried to sell a story about me to TMZ. Thank goodness, TMZ could see right through the sham of that story. This woman claimed that I beat her up in a nightclub because she was a lesbian. That is fuckin’ crazy. Bitch, I didn’t even know you was a woman.

Thank God TMZ didn’t believe that because I did beat the shit out of her, I am not gonna lie.

It was her fault, I had no choice. I came into the club minding my own business and a woman came up to me, and she goes “Oh my God, Dave Chappelle.” And I was just being reciprocally nice. “Hey, miss, how are you?” Blah, blah, blah. Benign talk, nothing to it. And all of a sudden this lesbian fellow stepped between us. “Hey n*gga, that’s my girl!” I said, “Yo, my man, back up.” Like that. She said, “I ain’t backing up off shit, n*gga, that’s my girl!” I said, “Bro, you gonna have to give me three feet, like this.” She said, “Stop calling me a man, motherfucker. I am a woman.”

I said, “What?” And then I looked deep in this n*gga’s cheek bones. And I said, “Oh my God, you are a woman.” This is too much for me to even wrap my mind around but I tell you what, I un-balled my fist immediately and I softened my posture so that she would know she is in no danger. I even changed the tone of my voice. I said softly, sweetly, like a pimp might say: “Bitch, I’m ’bout to slap the shit out of you.”

The bit shows how Chappelle leans into the persona of homophobic comedian in The Closer. A comedian’s persona can be a character distant from the performer’s “real” self, an exaggerated version of the performer, or virtually indistinguishable from them (Double Reference Double2014:121–34). Because “there are elements of authenticity in exaggerated personas” as well as “elements of exaggeration in comedians who apparently go onstage as a naked self” (133), the second and third types of personae are often hard to tell apart. Chappelle’s persona appears to be the performer Dave Chappelle; as such, his performance of homophobia both invites and preempts the cancel culture that is his purported target. This bit is structurally brilliant comedy containing a series of surprising punchlines: firstly, that the story offered to TMZ was a “sham” not because Chappelle didn’t beat the butch lesbian up but because he misrecognized her gender; secondly, that Chappelle, on realizing he has misgendered the lesbian, changes his posture and tone in line with the bus stop man’s “I don’t hit women” stance; and thirdly, that he does hit her. Rather than defending himself against the accusations of homophobia that have plagued his recent career, Chappelle performs the role of gender-normative homophobe.

Chappelle’s provocation lies in the conventional rather than faithful authenticity of comic persona. There are several such moments in The Closer, as when Chappelle discusses transgender comedian Daphne Dorman’s response to his offer to have her open for him whenever he performed in San Francisco: “And she grabbed me real tight, hugged me, squeezed me. And I pushed her off violently, ’cause I’m transphobic.” In these moments, Chappelle plays with the relationship between persona and performer. Chappelle has had his share of public confrontations, some of which are the basis for bits in The Closer. For example, he tells the story of a gay man who called the police on him during a verbal altercation at a bar in Austin, Texas, during which Chappelle called the man a “bitch-ass n*gga.” Photos and video of the incident as well as an account of what happened from the perspective of the other man, Chad Laboy, are available online (Butterfield Reference Butterfield2020). But I could find no coverage of the story of beating up a lesbian outside of reactions to The Closer; indeed, part of the set-up of the bit is that TMZ did not run the story because they “could see right through” it. It is worth noting that I found no coverage of Chappelle engaging in physical violence of any sort. But my point is not about the difference between verbal and physical violence, though Chappelle emphasizes this distinction with the title of Sticks and Stones; nor is it unconventional for comedians to mix events from their lives with invented scenarios. Instead, I am interested in the fictionality of the bit about beating up a lesbian because it highlights a difference in Chapelle’s and Gadsby’s framing of persona. In providing the real ending to the bus stop story, Gadsby collapses the distance between her comic persona and her sense of self, arguing that performing a humorous, fictionalized version of her own traumatic story was harming her (Balkin Reference Balkin2020:72, 74). Chappelle’s bit about beating up a lesbian, in contrast, relies on an unmarked but significant distinction between persona and performer. That is, it relies on at least some of the audience understanding that the performer is not quite the same as his persona, precisely because Chappelle leans into the idea that he is violent.

It is likely that some portion of Chappelle’s audience in The Closer — who laugh uproariously, though there are also moments of hesitation — assume no difference between persona and performer, imagining that Chappelle really did beat up the butch lesbian and that it is funny. Some other portion of the audience might assume that Chappelle did not really beat up the lesbian but would still think the idea of a lesbian getting beaten up is funny. Both groups of these hypothetical audience members are the sort Dave Chappelle of 2005 would have had qualms about, if we entertain the premise that his 2021 aims are critical rather than homophobic. But more of the audience, I suspect, would say that a lesbian getting beaten up in real life is not funny, but Chappelle’s jokes about it are. Chappelle makes a version of this distinction with the title of Sticks and Stones, and Sarandos’s claim that art does not cause real-world harm is an extension of the same logic. Danielle Fuentes Morgan effectively dismantles Sarandos’s claim when she notes how the tropes of the 19th-century minstrel stage “were used to support chattel slavery, recruit KKK members, and enact continuing violence against Black people” (2021). Gadsby likewise emphasizes how art and words do harm in her Instagram response to Sarandos, who referenced her as an example of Netflix’s diversity in his defense of Chappelle: “Now I have to deal with even more of the hate and anger that Dave Chappelle’s fans like to unleash on me every time Dave gets 20 million dollars to process his emotionally stunted partial worldview. You didn’t pay me nearly enough to deal with the real-world consequences of the hate speech dog whistling you refuse to acknowledge, Ted” (Gadsby Reference Gadsby2021). As well as being untrue, the claim that art and words do not cause real harm is not very interesting, though it has dominated much of the public debate around The Closer. Footnote 9 The “just jokes” argument has been well refuted, but there is a better point to be made about the occasion and contract of stand-up, where a comedian’s words register differently than they would in conversation. Here, again, my point is not that performance is “not real” and therefore exempt from scrutiny; it is that comic persona (sometimes subtly, sometimes radically) and the situation of utterance are traditionally understood to license different kinds of speech.

Figure 3. Hannah Gadsby responds on Instagram to Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos’s defense of Dave Chappelle during the controversy sparked by The Closer. 15 October 2021, www.instagram.com/p/CVCiLl9FWoB/. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)

Comic License vs. Cancel Culture

Chappelle insists that those who object to The Closer as homophobic and transphobic “must watch The Closer in its entirety” before he will meet with them (Chappelle Reference Chappelle2021). Chappelle wants people to consider The Closer as comedy with a critical point to make; that is, he wants it to be considered as a particular kind of speech. He wants the latitude conventionally afforded by comic license. As Debra Aarons and Marc Mierowsky note, the audience can revoke comic license at any time by not laughing, by booing, or by leaving (2017:160). Chappelle’s live audience keeps laughing, despite some moments of hesitation, such as when Chappelle makes a joke about “Space Jews,” or the Chinese origins of Covid-19; still, they do not revoke the license. “It is going to get way worse than that,” Chappelle warns, framing the show as intentionally overstepping the bounds of what he is allowed to say. In a 2021 interview, Chris Rock argues that the dynamics of comic license make cancel culture unnecessary: “when you’re a comedian, when the audience doesn’t laugh, we get the message. You don’t really have to cancel us because we get the message. They’re not laughing” (in McCarthy Reference McCarthy2021). An audience can revoke comic license for many reasons: because the comedian is incompetent, or offensive, or simply unable, under the circumstances of a particular performance, to read the room and adjust their material in a way that makes the audience laugh. The subject matter deemed unacceptable to an audience will necessarily change from room to room. Thus, under the conventions of comic license, there is no particular thing that comedians “can’t say,” even as the history of stand-up is rife with comedians who have tested and overstepped the limits of what an audience will accept. According to Rock, cancel culture is superfluous to this system and “disrespectful” to the live audience whose role is already to judge the content (in McCarthy Reference McCarthy2021).

Chappelle implicitly makes the same point in The Closer in his account of the time Daphne Dorman opened for him, bombed, but then won over the crowd through her handling of a heckler during Chappelle’s performance. Chappelle has been criticized for “exploiting the death of a friend” (Gay Reference Gay2021) in this section of the show, though Dorman’s sisters maintained in text messages to The Daily Beast that Daphne found Chappelle gracious and funny (Roundtree Reference Roundtree2021). My interest is in how Chappelle uses this story to argue that the live-audience contract of comic license facilitates better communication than the identity politics associated with cancel culture. Following Dorman’s bombed opener, Chappelle says, she good-naturedly took a seat in the audience rather than leaving in disgrace. Dorman, who was drunk, started talking to Chappelle during his set, to the audience’s displeasure:

And a guy in the back of the room stood up and Daphne’s hair was dyed blonde at the time and the guy screamed out, and his energy felt wild as fuck. He said, “Hey Daphne!” and everybody got clamped, they got tense. We didn’t know who was a heckler or active shooter, and he said, “Does the carpet match the drapes?” It was fucked up. The whole crowd kind of groaned, ’cause it was so like, mean. Everybody groaned, except for Daphne. She kind of laughed, which was weird. And she didn’t even look all the way back. She said, “Sir, I don’t have carpets I have hardwood floors.” Just like that. Just like that.

Boy, when she said that shit, it blew the roof off the place. Cut through all the tension, with that one joke. She had made up for 45 minutes of a stinker of a show. And after that, she could do no wrong. And I kept on rocking, and she kept on talking to me. And then the show became something cooler than a show. It became like a conversation between a black man and a white trans woman and we started getting to the bottom of shit. All of them questions that you think about that you’d be afraid to ask, I was just asking them and she was answering them and her answers were funny as shit. The crowd was falling out of their chairs and at the end of the show, I go, “Well, Daphne,” I said “Well, that was fun.” I go, “I love you to death, but I have no fuckin’ idea what you’re talking about.” The whole crowd laughed except for Daphne. Man, she looks at me like I’m not her friend anymore. Like I’m something bigger than me, like I’m the whole world in a guy. Then she said, “I don’t need you to understand me.” I said, “What?” She said, “I just need you to believe,” just like that, she goes, “that I’m having a human experience.” And when she said it the whole crowd kind of gasped. And I gave the Fight Club look. I said, “I believe you, bitch.”

Because she didn’t say anything about pronouns. She didn’t say anything about me being in trouble. She said, “Just believe I’m a person and I’m going through it.” I know I believe you, because it takes one to know one. (in Lathan Reference Lathan2021)

At the end of the show, as Chappelle reports it, Dorman got a standing ovation and Chappelle invited her to open for him whenever he was in San Francisco. Chappelle presents Dorman as the opposite of an oversensitive snowflake; instead, she is someone who can take a mean-spirited joke and diffuse the tension it creates with a comeback that shows she is funnier than the mean audience member. In the process, Dorman gets the audience on her side. The point Chappelle tries to get across with this story is that because comic license relies on real-time negotiation and dialogue, it can facilitate communication that can cut across (without negating) differences of race and gender.

But the era of the Netflix comedy special amplifies a change that was already underway in televised stand-up: the principle that Andrea Greenbaum (following Isocrates) calls kairos, or situatedness, gets recorded without being sustained: the live performance situation, including audience responses, is filmed, but the recording is edited and the Netflix viewers are in a different situation than the live audience. In live stand-up the comedian must respond flexibly to the exigencies of a discourse situation in order to maintain control of the room (Greenbaum Reference Greenbaum1999:40). While stand-up is conversational, involving direct communication in the present tense that “acknowledges the performance situation” (Double Reference Double2014), it is also rhetorical and persuasive (Greenbaum Reference Greenbaum1999:33). The comedian does most of the talking and most audience responses are conventionalized (laughter is part of the rhythm of jokes), but individuals can interject or heckle and the audience has the collective power to revoke the comedian’s permission to speak. There are several moments in The Closer that illustrate these dynamics; for example, when Chappelle notes that he is “not indifferent to the suffering of someone else,” he begins to describe an anti-trans North Carolina law that says people “must use the restroom that corresponds with the gender they were assigned on their birth certificate.” A portion of the audience cheers and Chappelle pulls them back: “No, no, no, no. No, that is not a good law. That is a mean law. No American should have to present a birth certificate to take a shit at Walmart, in Greensboro, North Carolina, where DaBaby shot and killed a motherfucker.” Australian trans comedian Cassie Workman sees this as a moment when “this thing has sort of gotten out of [Chappelle’s] hands”; she notes that Chappelle’s audience clearly wants him to “go further and be meaner, and he has to shut them down” (in Faruqi Reference Faruqi2021). This moment is good evidence of anti-trans sentiment in Chappelle’s audience, but the live performance has not gotten out of Chappelle’s hands, in that he easily regains control of the room, steering the audience back to laughing in the places he intends. Indeed, the readiness of Chappelle’s line about DaBaby (a callback to an earlier joke about the rapper, whose homophobic comments made more headlines than his violent behavior) suggests he might have anticipated the cheers for North Carolina’s anti-trans bathroom law, though Chappelle is also skilled enough to improvise. In contrast, the performance situation in mediatized stand-up is retained insofar as the live audience’s responses are recorded and influence reception, but there can be no present-tense response to the much larger, asynchronous digital audience; the “room” is gone and with it, the comedian’s opportunity to steer the audience back to laughing at the right things. And if you are not having fun anymore, you can turn off the television or click away, as poet Saeed Jones did partway through The Closer when he felt betrayed by Chappelle’s politics ( Jones Reference Jones2021), but the comic cannot respond in real time as they might to a heckle, a walkout, or laughter at the wrong thing during the taping. This is different than the live contract of comic license, though the audience still has a choice.

Figure 4. Transgender activist and comedian Daphne Dorman defends Dave Chappelle on Twitter during the controversy sparked by his special Sticks and Stones (2019). 29 August 2019, twitter.com/DaphneDorman/status/1166937728681791488. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)

Chappelle’s requirement that people watch the whole show before he will debate them and Gadsby’s post about his fans unleashing on her on social media speak to the ease with which digitally disseminated stand-up bleeds into public discourse, giving rise to different kinds of speech experienced under different conditions. Footnote 10 These include “dragging,” the practice of publicly humiliating someone on social media. Chappelle both invokes and dismisses this sort of speech in The Closer: “When Sticks and Stones came out a lot of people in the trans community were furious with me and apparently they dragged me on Twitter. I don’t give a fuck, ’cause Twitter is not a real place.” If Chappelle really didn’t care, he probably would not have made a stand-up special specifically responding to the public response to his recent work. The statement also contradicts his response to Dorman’s defense of Chappelle on Twitter when he was accused of transphobia. Dorman tweeted:

Punching down requires you to consider yourself superior to another group. @DaveChappelle doesn’t consider himself better than me in any way. He isn’t punching up or punching down. He’s punching lines. That’s his job and he’s a master of his craft. (Dorman Reference Dorman2019b)

In The Closer, Chappelle responds, “Beautiful tweet, beautiful friend, it took a lot of heart to defend me like that, and when she did that the trans community dragged that bitch all over Twitter.” Dorman’s tweet was real enough to mean something to Chappelle. Reflecting on the cause of Dorman’s suicide soon after, Chappelle speculates, “I don’t know if it was them dragging or I don’t know what was going on in her life but I bet dragging her didn’t help.” Chappelle’s point is about dragging as an aspect of cancel culture, showing how the disciplinary enforcement of “woke” identity politics harmed a trans woman who thought differently. But as journalist Michael Hobbes notes, there is no evidence that a woke mob dragged Dorman; her tweet had only 12 replies in 2019 and they were supportive. And even if we understand Chappelle’s woke mob as “the Platonic ideal of an alt-right clickbait story” (Hobbes Reference Hobbes2021) fictionalized for performance, the example also neatly contradicts Chappelle’s “sticks and stones” stance and makes Gadsby’s point for her. Indeed, when Chappelle frames The Closer as being about cancel culture, he puts comedy forward as a genre capable of saying something critical about the discourse situations of social and popular media. As Helen Lewis notes in her astute response to The Closer, Chappelle “spends most of the show in an implicit dialogue with an audience outside the room” (2021).

In so doing, Chappelle invites engagement outside the conventions and implicit ethics of comic license he puts forward with the story of Dorman’s handling of the heckler. One kind of engagement he invites is cancellation, which registers an impasse in mediatized public discourse that the live dynamics of comic license are less well-placed to address. Roxane Gay gives a good summation of the impasse in public discourse on comedy in her response to The Closer:

We generally have the same debates about comedy over and over. Let’s address those upfront: Art should be made without restriction. Free speech reigns supreme. Sometimes good art should make us uncomfortable, and sometimes bad people can make good art. Comedians, in particular, are going to punch up and down and side-to-side.

Also true: Comedy is not above criticism […]. It’s just laughs, right? Lighten up. All criticism is forestalled with this setup, in which when you object to anything a comedian says, you’re the problem. You’re the one who’s narrow-minded or “brittle” or humorless. (Gay Reference Gay2021)

Chappelle does forestall criticism in The Closer in that most critical responses to it wind up performing examples of the sorts of rhetoric Chappelle is mocking. As conservative political commentator Andrew Sullivan notes, “You could write it yourself, couldn’t you? 1. He’s a bigot […]. 2. He’s out of date” (2021). But while Chappelle certainly argues that people should be able to take a joke, he does not frame comedy as “just laughs”; instead, he positions comedy as a powerful discourse with its own superior rules of engagement. As I have shown, the live-audience contract of comic license is not sufficient to account for how comedy circulates in a larger, digitized media landscape. Comic license can nonetheless help us to get away from the rhetoric of whether art and speech are “real” or “free”; instead, it draws our attention to genres of speech and conditions of performance that already shape what can be said, and where, and by whom.

Infelicity: The Punchline

But the question remains: what kind of speech is The Closer, if the logic of comic license cannot encompass it? J.L. Austin’s influential theory of performative speech posits that “the issuing of an utterance is the performing of an action” ([1962] 1975:6). For performatives to produce their intended effects, the correct context and conditions must be in place. “I quit,” said to one’s boss, is a good example. Austin famously excludes theatrical speech from his theory because it operates outside of “ordinary circumstances” (22); jokes too are excluded because “the words must be spoken ‘seriously’ and so as to be taken ‘seriously’” (9). Nonetheless, theatre and performance scholars have long found Austin’s performatives useful and Aarons and Mierowsky have analyzed how speech acts shape the relationship between performer and audience in stand-up. Footnote 11 Aaron C. Thomas suggests that “the constant use of performative by theatre scholars” reflects a belief that performances “make things happen in the world, and […] immediately produce those effects” (2021:21). Aarons and Mierowsky make a similar, genre-specific case that “standup performers use the complex communicative context of the comedy performance as a way of getting people to do things in the world” (2017:159). Where Aarons and Mierowsky leave the “perlocutionary success of the speaker’s intention” an open question (159), Thomas emphasizes the failure (Austinian “infelicity”) that inheres in performance, asking whether “our very desire for felicitous performatives” might “be working to obscure the manifold possibilities of performance as such” (22). Indeed, Sheila Lintott argues that stand-up “maximizes the experience of failure,” not least because “stand-up stands alone in requiring a live audience for its rehearsal” (in Oppliger and Shouse Reference Oppliger and Shouse2020:214). Chappelle’s performance, then, is the kind of felicitous infelicity whereby the success of the speaker’s intention produces the effect of cancellation. By the “effect” of cancellation I mean both that cancellation is what Chappelle gets people to do in the world, using the expanded communicative context of The Closer — and that Chappelle’s career has not been especially harmed by it. The effect of cancellation (or the cancellation effect), in this latter sense, is perceptible not in Chappelle’s disappearance from Netflix or other platforms but in his ubiquity in the mediatized public discourse that condemns him.

Chappelle rehearsed such felicitous infelicities in “Epilogue: The Punchline,” the secret bonus ending to the Netflix release of Sticks and Stones. The epilogue is a predecessor to The Closer in its framing of liveness, in its structural position at the end of a show that must first be watched all the way through, and in its engagement with absent critics. While Sticks and Stones was filmed in Atlanta, the 23-minute epilogue was filmed during his Dave Chappelle on Broadway performance at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in New York City. Unless they already knew it was there and skipped ahead, Netflix viewers had to watch Sticks and Stones all the way through to reach the epilogue, in which Chappelle invites his live audience to ask him questions. At the start of the Q&A, Chappelle notes, “I understand why I could hurt some people’s feelings, so tonight […] I’m going to give you an opportunity that I rarely give anybody. I’m going to let you say whatever it is you need to say to my face.” Footnote 12 The offer seems to promise the live audience access to the “real” Chappelle and to suggest that some of them might be upset with him. Notably, the audience questions do not broach the subjects of homophobia, transphobia, or cancel culture at all; if the epilogue was designed as a face-to-face opportunity for Chappelle’s detractors to work through their issues with his material, it was not a success. But I do not believe it was designed this way. As Chappelle says in the epilogue, the Broadway audience paid up to $800 per ticket to see him. None of their questions are accusatory or suggest hurt feelings. In combination with The Closer, the epilogue establishes speaking to an audience outside the room as a through line in Chappelle’s late work, with the difference that he frames his speech as a response to questions the live audience have not asked.

It is Chappelle who steers the epilogue to what are now his pet topics: in response to the audience question, “is there anything you’ve learned from another comedian that you feel like will stay with you for life?” Chappelle first gives an answer about considering comedians his family and then, unasked, tells a story about two audience members who attended his show at the Punch Line, a club in San Francisco. The first, a cisgender white woman, stood up while Chappelle was telling #MeToo jokes and said, crying, “You can’t say that!”; after announcing she was a sexual assault survivor, the woman walked out. The story draws familiar lines in the sand as the offended, humorless #MeToo feminist attempts to police what the comedian can say. The second audience member is Daphne Dorman, who laughed uproariously at Chappelle’s trans jokes. After the show, Chappelle says in the epilogue, he had a drink with Dorman at the bar during which she raised the “bad rap” Chappelle gets for his trans jokes and proposed that Chappelle “normalized transgenders by telling jokes about us.” Chappelle tells the audience, “And I’d never thought about that, it had never occurred to me. And we started making out. And then, like I…I reached up just to see what it felt like. And it felt like pussy, it did” (Dean’s Comedy Channel 2021). The bit makes a serious point about how jokes can normalize as well as marginalize and then shifts to a fictionalized make-out and groping session. The joke both enacts and punctures the normalization for which Dorman praised Chappelle with a vocally deemphasized punchline (“it felt like pussy”) that emphasizes anatomical difference when the audience laughs at it. The two stories, which are primarily addressed to Netflix viewers and critics, model political orientation through anecdotes about audience behavior.

But there is one live audience question in the epilogue whose answer raises yet again the intentions, effects, and framing of Chappelle’s speech in these specials. Asked about his “favorite book of all time,” Chappelle replies, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” He does not elaborate and moves on to the next question. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass ([Reference Douglass1845] 2014) is the most famous example of a slave narrative, an autobiographical genre that details a former slave’s life and escape to freedom. Literacy often sparks the quest for freedom in this genre, but Douglass’s narrative is unique in taking readers past the point of his escape and concluding, instead, with his becoming an abolitionist lecturer. Foundational to this text is the premise that written and performed rhetoric has effects in the world; indeed, the book from which Douglass learns to read, The Columbian Orator (1797), contains a dialogue between a slave and his master in which “The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master — things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master” (Douglass [Reference Douglass1845] 2014:39). The premise of this Enlightenment text is that it is possible to have a good-faith dialogue in which the slave’s articulacy and rationality cause the master to recognize his humanity and free him. But although The Columbian Orator influenced Douglass profoundly, he was not naïve about oratory’s power to free him, or to make people believe him. Douglass published the Narrative in part as a response to critics who doubted that a black man who was so eloquent on the lecture platform could really have been a slave (Lampe Reference Lampe1998:255). Its subtitle, “Written by himself,” shores up the truth claim of autobiography. But as the necessity of making such a claim suggests, it was not enough: although the published narrative did help Douglass’s credibility (and immediately became a bestseller), it was also buoyed by the written testimonies of white men in the form of prefaces, a convention of the fugitive slave narrative that speaks to the difficulty of making credible truth claims as a black man. Douglass thus puts forward the dialogue between slave and master in The Columbian Orator as an idealized model of what rhetoric can do in the world even as the framing Narrative comprehends and mediates the social conditions that are barriers to perlocutionary success.

The conditions under which Douglass speaks — where testimony repeatedly comes up against racist skepticism — are part of the history of the conditions under which Chappelle speaks. But while Chappelle’s chosen genre, stand-up, is often autobiographical, as I noted earlier, its perceived authenticity is conventional rather than faithful; that is, it’s normal to make some things up. Whether or not we find him funny, many of the ways Chappelle fictionalizes in the epilogue to Sticks and Stones and in The Closer are recognizable as such in context, as when he talks about violently pushing Dorman off him, groping her, and, arguably, when he discusses beating up the butch lesbian. In contrast, Chappelle’s story of Dorman being dragged on Twitter, narrated in a “serious” part of the show, feels (in the face of Hobbes’s evidence to the contrary) more like a lie. The difference is partly that Chappelle is not leaning into a transphobic persona as he tells this story; he has exaggerated events rather than himself in a part of the show that seems to claim to be true. Footnote 13 And rather than changing the details of his own story to make it funny, as in Pryor’s account of setting himself on fire or Gadsby’s first iteration of the bus stop story, Chappelle attributes a fictional cause to Dorman’s tragic story to make a moralizing point. That viewers generally perceived it to be true is shown by the story’s adoption in respected media such as The Economist (Hobbes Reference Hobbes2021) and The Atlantic (Lewis Reference Lewis2021) as well as in new replies to Dorman’s tweet about punching lines following the release of The Closer. Footnote 14 This part of his show structurally resembles Gadsby’s refusal to make audiences laugh for long stretches of Nanette, in which she was accused of performing lectures rather than comedy (see Berkowitz Reference Berkowitz2020); the tone is didactic. Thus, while I agree with Goltz’s assertion that in a contemporary “cultural climate where comedy is so often at the center of controversy, too often we engage comedic work as if it were parallel to political speech” (2017:6), the humorless sections of Chappelle’s show also invite this misapprehension. And as in Nanette, Chappelle seems to have dropped his persona in favor of his “real” self, though the dropping of the mask is part of the performance. If we consider The Closer as a performance that is not separable from its extended communicative context, then it is a series of bad-faith speech acts: an invitation to cancel that traps commentators into performing scripted actions and rhetoric; a valorization of dialogue and liveness that addresses an absent, mediatized audience; and a serious story that misattributes Dorman’s suicide to the tweets of a fictional woke mob.

“Stop punching down on my people”

In The Closer, Chappelle tells the story of a trans woman who confronts him in a club about transphobia in his comedy and asks, “Do you mind not punching down on my people?” “Punching down” in comedy is a frowned-upon practice of making jokes at the expense of groups with less power. Chappelle notes his hatred for the phrase, which has followed him around for 16 years since he performed transgender jokes in Oakland. When the woman in the club confronted him, Chappelle tells the audience, “She kept calling transgenders ‘her people.’ Ain’t that weird? ‘My people this, my people that.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, your people? Were you all kidnapped in Transylvania, brought here as slaves?’” Chappelle’s language and attitude here suggest a cisgender straight guy persona more clueless than Chappelle actually is. Footnote 15 The joke questions, as Chappelle does several times in the special, whether a black man making a joke about a white trans woman can be called punching down. The joke is also about what makes a group a “people,” and Chappelle’s punchline asserts the legitimacy of a group identity conferred by a shared history of enslavement, in the Moses “let my people go” sense or as per the legacies of American slavery. It questions whether blackness and transness might be different orders of experience.

“My people” is also an assertion of representation. Gadsby and Chappelle have both traced discomfort with their own comedy to the pressure to represent for queer and black people, respectively. Gadsby refers to LGBTQ folk as “my people” throughout Nanette, but she also notes, “I don’t think I’ve been representing my people as much as I should be.” Chappelle has linked his discomfort with the blackface pixie sketch that led him to quit Chappelle’s Show to his own felt responsibility to represent; as he told Oprah in 2006, “I don’t want black people to be disappointed in me for putting that [message] out there…It’s a complete moral dilemma” (Oprah.com 2006). In Nanette Gadsby discusses the fatigue such pressure to represent engenders. She tells the story of a fan who wrote to her and said:

“You owe it to your community to come out as transgender.” All jokes aside, I really do want to do my best by my community. I really do. But that was new information to me. I’m not…I don’t identify as transgender. I don’t think even lesbian is the right identity fit for me, I really don’t. I may as well come out now. I identify…as tired. I’m just tired.

Gadsby’s joke resonates with her trademark slowness and low-affect comic delivery as well as marking her fatigue with the politics of representation. But where Nanette diagnoses comedy as part of the problem, in that it does not allow Gadsby to represent her full self or speak her whole truth, Chappelle frames comedy as part of the solution in his account of how Dorman handled the heckler, only to announce at the end of the show that he is going to quit telling particular kinds of jokes.

In The Closer, Chappelle reinforces the idea that comedy can trump other kinds of affinity when he claims Dorman as one of his tribe after her death: “And I don’t know what the trans community did for her but I don’t care, because I feel like she wasn’t their tribe, she was mine. She was a comedian in her soul.” The low-hanging fruit is to note that Chappelle ignores intersectionality; Dorman was a trans activist as well as a comedian. Footnote 16 But I am more interested in the change in logic: are comedians more convincingly a “tribe” or a “people” than trans folk? Have the culture wars so united and elevated comedians in what Lewis calls the “hierarchy of suffering” (2021)? The Closer’s ending amplifies these questions. After noting that “taking a man’s livelihood is akin to killing him” and decrying campaigns to cancel DaBaby and comedian Kevin Hart over their homophobic speech, Chappelle finishes:

LBGTQ, L-M-N-O-P-Q-Y-Z, it is over. I’m not telling another joke about you until we are both sure that we are laughing together. I’m telling you this is done. I’m done talking about it. All I ask from your community, with all humility, will you please stop punching down on my people? Thank you very much and good night. Footnote 17

As Workman notes in her response to this ending, “Dude, you just did 35 minutes of jokes about us!” (in Faruqi Reference Faruqi2021). The man who insists in Sticks and Stones on the difference between words and physical violence conflates loss of livelihood with loss of life. The man who hates the phrase “punching down” deploys it. The man who queries what sort of shared experience makes a group a people now uses the term loosely to denote African Americans, comedians, and celebrities. Gay’s reading of this ending is compelling:

If it wasn’t clear from his words, the snapshots of him with his famous pals in the closing credits of “The Closer” make it abundantly clear that Dave Chappelle’s people aren’t men or women or Black people. His people are wealthy celebrities, and he resents even the possibility of them facing consequences for their actions. (Gay Reference Gay2021)

But is this all there is to it?

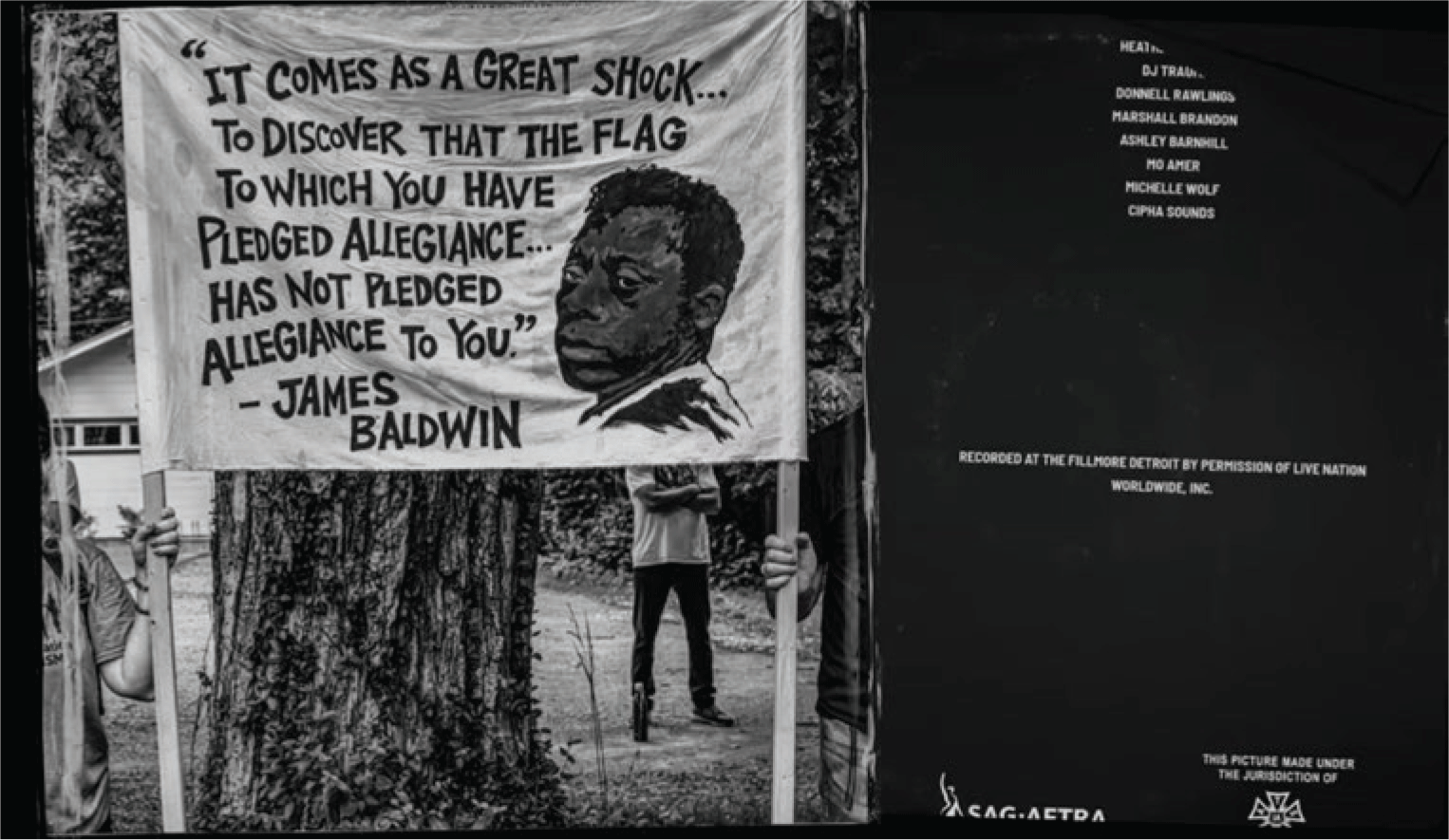

In one respect, the photos of Chappelle with celebrities during the credits of both Sticks and Stones and The Closer are yet another inversion of Nanette, in which Gadsby condemns the celebrity culture that has excused misogynistic and abusive behavior by Pablo Picasso, Louis C.K., Harvey Weinstein, and Bill Cosby on the basis of “genius.” Footnote 18 I cannot help but also think about the photos of Chappelle with celebrity friends in light of the testimonials that accompany and shore up the truth claims of Douglass’s Narrative. The Closer’s credits include photos of Bill Murray, Jon Stewart, Kevin Hart, Chris Tucker, Jerry Seinfeld, David Letterman, Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def ), Kanye West, and Norm Macdonald (to whom the special is dedicated), among others. The photos seem to vouch for Chappelle, or at least to make it more difficult to dismiss him. Interspersed with the celebrity photos are shots of Chappelle’s family as well as images of people holding protest signs that include a quote by James Baldwin and the slogans “Black Trans Lives Matter” and “Stonewall.” One way to read the inclusion of the protest signs is that they frame The Closer with yet another kind of speech that strives to create change in the world, and with the protest movements that Chappelle distinguishes from politically correct speech and cancel culture in the special, as when he states his respect for “old school” Stonewall gays over “newer,” “sensitive,” “brittle” gays. The protest signs might also be said to fulfill Chappelle’s promise at the end of the special by introducing non-joking genres of speech about LGBTQ people. But they leave a sour taste after a special in which Chappelle proclaims himself “team TERF” (trans exclusionary radical feminist).

Figure 5. Jerry Seinfeld and Dave Chappelle in the closing credits to The Closer. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)

The sour taste is the crux of the special. The Closer’s ending shows Chappelle’s recognition that the necessary conditions for “laughing together” are not in place. Moreover, by contradicting the key points he has laid out across two comedy specials, his final lines frame The Closer as an exercise in misfire. The exercise implicates Chappelle as well as the leftist rhetoric he ridicules. By this logic, the cancellation effect is the special’s best success, and I begin to reconsider who the dupes are: the critics and social media commentators who walk into Chappelle’s trap when they condemn him, or the live audience who license speech that is not primarily addressed to them? Perhaps I am also one of the dupes for seeing something worthy of sustained attention in Chappelle’s bad faith. But I can’t escape the feeling that The Closer’s infelicities enact something essential about public speech at the present time.

Figure 6. One of several images of protest signs in the closing credits to The Closer. (Screenshot by Sarah Balkin)