Significant numbers of women of color major in political science as undergraduates, but they persistently are less likely than other subgroups to complete graduate degrees, obtain doctorates, find faculty positions, and successfully advance through promotion and tenure. The number of job candidates from underrepresented backgrounds is much smaller than the number of white non-Latinx candidates (Jackson and Super Reference Jackson and Super2018). Women of color face barriers including lack of sponsorship and mentorship, financial resources, and significant familial responsibilities in their pursuit of higher education and subsequent careers in political science—one of the most male- and Anglo-dominated fields of study in the social sciences.

To combat the erosion of women of color in our discipline, we hosted a series of workshops in 2013,Footnote 1 2015, and 2017 to foster deep mentoring and investigate the experiences of women of color in political science from graduate school through faculty and administrative positions. Workshop participants represented a diverse mix of graduate students, faculty in various positions, and administrators—and also was varied by ethno-racial group, including sizeable numbers of Black, Latina, and Asian-descent women. The workshops had powerful positive impacts on our participants, as measured in pre- and post-workshop surveys and focus groups and also as noted in unsolicited social media testimonials.

In the surveys, we asked respondents to rate their confidence in the following areas: navigating the job market, getting tenure, post-tenure strategies for advancement, teaching and identity in the classroom, public intellectualism, receiving and providing mentoring, and negotiating a job offer. Across all areas, significant proportions of our respondents indicated a lack of confidence before the workshop and higher levels of confidence after participation (figure 3).

Figure 3 Pre- and Post-Workshop Confidence, Women of Color in Political Science 2013–2017

Participation in the workshop significantly increased participants’ confidence in knowledge and skills across a variety of areas, which is evidence that progress toward their inclusion as full members in the discipline was uneven and fragmented. The results are a serious wake-up call for those who laud the increasing diversification of our graduate student and faculty ranks without recognizing the harsh reality that women of color often face in the profession. There is considerable room for improvement in political science—and the academy in general—in the representation, mentoring, and treatment of women of color (Lavariega Monforti Reference Lavariega Monforti, Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2013).

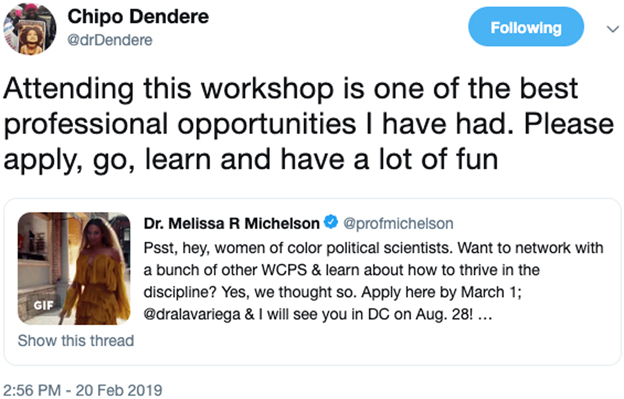

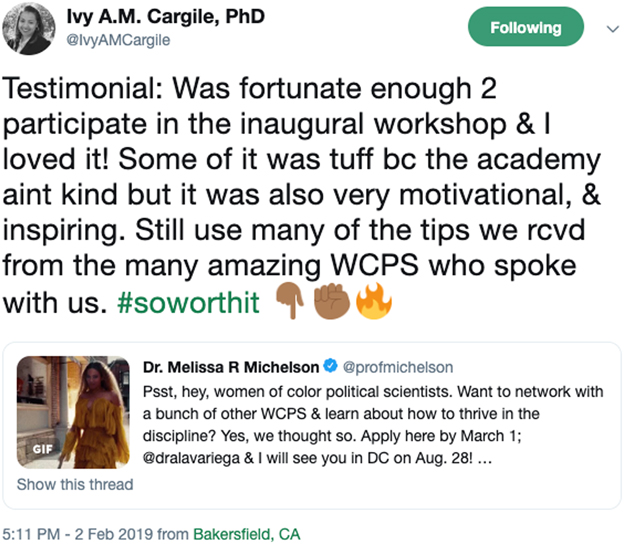

The bottom line is that these workshops were enormously effective; the quantitative and qualitative data we collected support this. Participants found the experience to be transformational. We know this because they keep telling us—unsolicited. Figures 4–6 are examples of their tweets in response to our most recent call for applications to apply.

Figure 4 Tweet from Dr. Angela X. OcampoFootnote 2

Figure 5 Tweet from Dr. Chipo DendereFootnote 3

Figure 6 Tweet from Dr. Ivy A. M. CargileFootnote 4

The survey results, as well as our focus-group evidence (Lavariega Monforti and Michelson, forthcoming), speak to the persistent invisibility of women of color in political science and the need for an intersectional approach to mentoring. The intersectional space that women of color inhabit must be recognized; women of color are not only people of color and not only women. Usually, they are mentored by scholars who are not women of color; although these mentors may be well intentioned, they are not fully able to understand the challenges faced by their mentees. Women of color are told that they are exceptional and are not provided opportunities to gain the tools to succeed. Whereas it often is perceived as impressive to be the first or ONLY fill-in-the-blank in your department, in actuality, it often is alienating and frustrating. It is difficult to break new ground and succeed as a graduate student or faculty member—or to effectively teach your students—when constantly treading water.

Whereas it often is perceived as impressive to be the first or ONLY fill-in-the-blank in your department, in actuality, it often is alienating and frustrating.

Our workshops provide participants with the space to develop these tools: networking happens differently, posse building happens, and skills are honed in a way that recognizes the full humanity of participants. In one full day, we fill significant gaps about how to thrive in the discipline that these scholars did not have the opportunity to fill during graduate school or at the institutions where they teach. What makes our workshops effective is that they center on the voices of women of color. We bring elders in the field together with rising scholars in an environment that nurtures deep networking and persistent interpersonal connections. Women of color do more than their share of service work and student mentoring at their home institutions, focusing on the success of others rather than their own. At the workshops they can focus on their own development, without demands being placed on them.

Connecting women of color with one another is the most significant way to create a pipeline from graduate school through tenure and promotion (and beyond). It is much more difficult to envision a future for yourself when you do not have an example to follow of someone like you: a role model to prove that your imagined future is possible. Bringing together senior women of color with graduate students and junior women of color proves that it is possible for those students and junior scholars to become senior scholars. Few departments (or colleges) provide for that opportunity. These workshops provide real-world examples of success stories and makes them tangible because participants are interacting with those senior women in an intimate space where they feel safe sharing their personal narratives.