Introduction

In the last decades, several scholars have raised their voices in defence of crucial interdisciplinarity in Egyptology, promoting a profound critique of the predominant studies and methodology, since it has been constituted as a Eurocentric philological discipline, usually working separately from archaeology (whose studies, in turn, usually understand written sources as ‘elite’ data) (Quirke Reference Quirke2015, 9). Although the philological tradition of Egyptology still prevails, the rejection of the conventional division between philologists and archaeologists is pronounced (Wengrow Reference Wengrow, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 49). In Bloxam and Shaw's words:

Does Egyptology have an identity crisis? If we look back to the last decade, then the answer would probably be ‘yes’. Over the last few years, there has been a gathering consensus that the discipline needs to seriously search for its identity and relevance within the social sciences if it is to survive as an academic field in its own right. (Bloxam & Shaw Reference Bloxam, Shaw, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 1)

It is the new generations of Egyptologists which have advocated most actively for such renovation. They have argued that Egyptology should rid itself of those precepts that remained largely unchanged, alongside the influence of Orientalism on the major Western academic institutions, to focus on comparative social sciences (Baines Reference Baines, Verbovsek, Backes and Jones2014, 578–84; Bloxam & Shaw Reference Bloxam, Shaw, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 2–4; Lauer Reference Lauer, Verbovsek, Backes and Jones2014, 68; Quirke Reference Quirke2015, 6). Despite the persistence of an Egyptology focused on ‘beautiful objects’ (Moreno García Reference Moreno García and Carruthers2014, 52), several scholars have promoted greater interdisciplinarity, as seen, for instance, in the initial comparative approaches of Trigger (Reference Trigger2003) for the ‘early civilizations’, Liverani (Reference Liverani2002) for Near Eastern studies and Moreno García and Pines (Reference Moreno García2020) or Barbieri-Low (Reference Barbieri-Low2021) for ancient Egypt and China. In that sense, one of the main social sciences incorporated into the Egyptological discourse is anthropology. Since the 1970s it has occupied a prominent role, although already with Egyptologists like Petrie some ethnographic considerations were appreciated (Bussmann Reference Bussmann2015, 1–2). This is manifested in the interest in little traditions (Bussmann Reference Bussmann and Ullmann2016, 42–4), including aspects such as diverse social spheres and ‘classes’, the articulation of the Egyptian worldview or microhistory studies (Moreno García Reference Moreno García, Frood and Wendrich2018). Other current innovative trends of research are, for instance, the one carried out by El Daly (Reference El Daly2005) or Riggs (Reference Riggs2014), dealing with aspects that earlier Egyptology had addressed without much self-criticism. Likewise, areas such as gender studies have recently experienced greater development and theoretical elaboration (e.g. Sweeney Reference Sweeney, Frood and Wendrich2011; Wilfong Reference Wilfong and Wendrich2010), and other innovative perspectives have also been incorporated, such as the history of emotions (e.g. McDonald Reference McDonald, Frood and Wendrich2020).

This paper aims to apply a methodology that allows us to understand ancient Egyptian society through a comprehensive approach, attending to the bias of the Egyptian evidence, since cultural studies have tended to ignore the historical and internal context of the culture under study (Lauer Reference Lauer, Verbovsek, Backes and Jones2014, 75–8). Sociology and other related social sciences provide fitter theoretical approaches than those used in previous Egyptological analyses (Moreno García Reference Moreno García2020, 7). A dialogue between social sciences and Egyptology is crucial for determining whether what is today called ‘social exclusion’ was (or was not) present in ancient Egypt.

Like other scholars of antiquity, the Egyptologists that have adopted sociological precepts have sometimes fallen into a certain simplism by applying concepts such as ‘class’, ‘elite’, ‘middle class’, ‘high culture’ and ‘low culture’ in an uncritical way, or the opposition between ‘official’ and ‘popular’ art and piety (e.g. Baines Reference Baines2013; Richards & Van Buren Reference Richards and Van Buren2000). However, many of these terms are still necessary for most of the Egyptological studies and, with all their implications in mind, their use is mainly accepted (Grajetzki Reference Grajetzki and Wendrich2010, 180–81). Besides, two historical periods have attracted interest to apply different sociological concepts, when social logics such as kinship and solidarity are more evident: the formation of the Egyptian state and the Middle Kingdom (e.g. Campagno Reference Campagno2006; Olabarria Reference Olabarria2020). However, Egyptology continues to show reluctance to implement them and, in practice, clings to its traditional articulation (Bloxam & Shaw Reference Bloxam, Shaw, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 23). Likewise, aspects such as economic and social history have included sociological studies to a greater extent, but often lack a theoretical framework (Moreno García Reference Moreno García and Carruthers2014, 57–9).

Social exclusion in ancient Egypt

Previous approaches

Social exclusion has been dealt with in ancient Egypt in a partial and, on most occasions, superficial way. Among the several Egyptological positions we find, on the one hand, the work of Jeffreys and Tait (Reference Jeffreys, Tait and Hubert2000). They consider that networks of solidarity prevailed in Egyptian society by emphasizing the representations of people with physical deformities and the ‘benevolence’ of certain texts. However, these assertions should be nuanced. Images of physically deformed individuals do not necessarily reflect inclusivity and need to be contextualized, since they are highly biased and ideologized (Baines Reference Baines2007; Nyord Reference Nyord2020). Moreover, texts also reproduce the elite standpoint, especially the autobiographies of the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom, which emphasize the charitable character and the cliché of the ‘good shepherd’ of socially prominent figures who sought the support of their community to gain greater independence from the central state (Assmann Reference Assmann2002, 93–105; Gnirs Reference Gnirs and Loprieno1996).

On the other hand, among the studies that advocate the existence of social exclusion in Ancient Egypt, Fischer-Elfert's contribution stands out. He has analysed this phenomenon through four case studies. The first deals with diseases that could lead to exclusion, entailing a physical separation for health reasons, such as leprosy (Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 33–90). The second analyses ‘hot’ persons (šmw/šmm), which he relates to cases of epileptic convulsions (Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 91–164). The third and fourth cases, based on the Teachings of Ani and the Misfortunes of Urmai (pPushkin 127), are the women known as ‘outsiders’, possibly as a result of adultery or prostitution (Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 165–231). Despite its pioneering character, Fischer-Elfert's work has several deficiencies. Besides being a purely philological approach, with little consideration of other evidence (with only Assmann's work as a theoretical basis), he makes risky assertions and comparisons, such as associating the term šmw with epilepsy (Laisney Reference Laisney2011, 118–20).

Remarkably, all the studies that have addressed social exclusion in ancient Egypt have not applied a theoretical framework from sociology. For a social phenomenon of such complexity, the lack of such a basis makes the research incomplete.

Theoretical framework

In order to establish a sociological framework appropriate for antiquity in general and Egyptology in particular, and useful for this study, it is necessary to contextualize the terms related to the individuals who might be considered marginalized or excluded.

There is not a precise and agreed definition of social exclusion, as its application in the Western world has referred to both material poverty and non-integration into the social fabric (Lister Reference Lister and Turner2006, 575). In its earliest applications, in the 1980s, ‘social exclusion’ alluded to marginalized segments of society in the peripheries of industrialized cities. Later, it became more widespread with the EU Poverty Programmes to avoid terms such as ‘poverty’ or ‘deprivation’ appearing in academic and policy publications (Peace Reference Peace2001, 18).

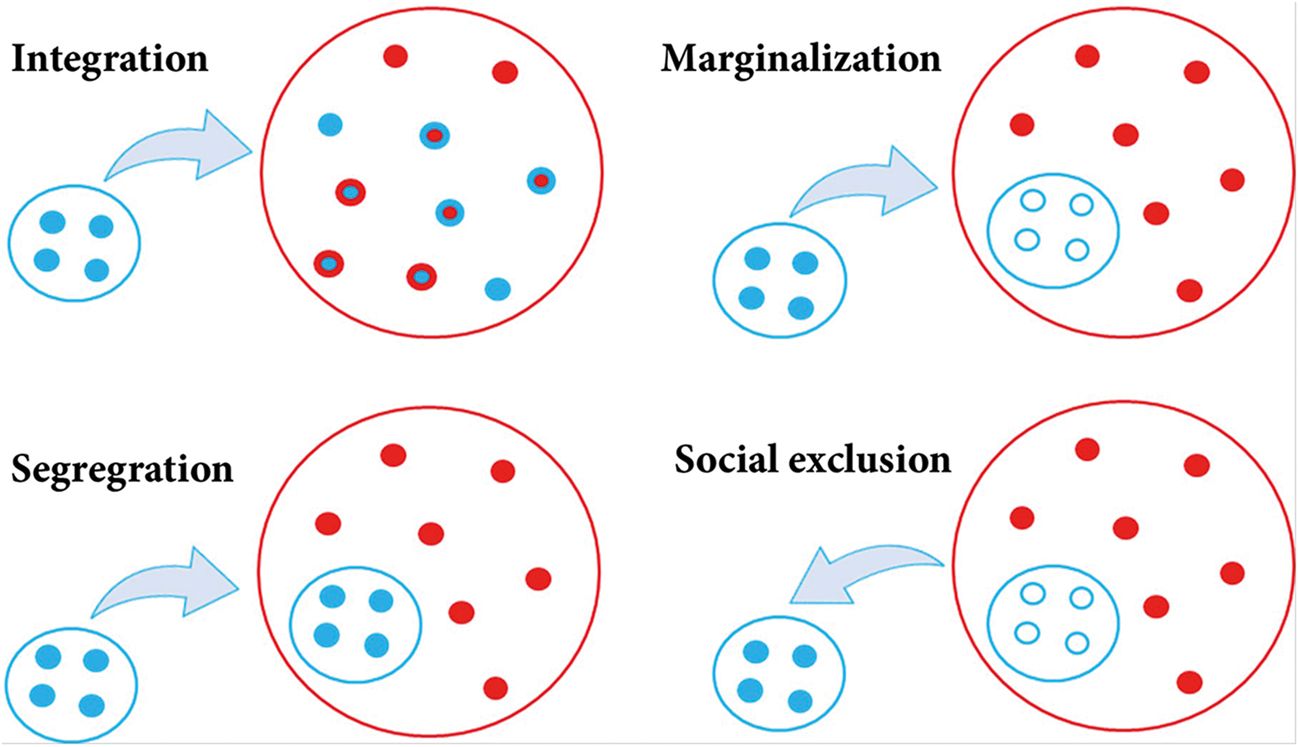

Sociology provides the main theoretical and methodological approach to this issue (Allman Reference Allman2013). To address this phenomenon, marginalization should be distinguished from social exclusion (Fig. 1). The former can be understood as a process by which members of a group who do not adapt to social prototypes are relegated to the margin, although they are not expelled or excluded because of the usefulness they may have for the rest of the group (see below). As for the latter, exclusion can imply a social rejection—which can also be physical—of those individuals who are not integrated into the social fabric of the group, since their agency and power are opposed to those that do fit the prototypes (Hogg Reference Hogg, Williams, Forgas and von Hippel2005, 250–51; Lister Reference Lister and Turner2006, 575).

Figure 1. Different forms of integration and exclusion. (Adapted from Fährtenleser CC0 1.0 [Wikimedia].)

Although most studies on social exclusion are usually limited to a modern time frame (Peace Reference Peace2001), some have dealt with it in a broader context, including Antiquity. Allman (Reference Allman2013), following the ideas of the sociologist and anthropologist D.F. Pocock, considers that the practices of social inclusion and exclusion are specific to hierarchical social groups, varying according to the social ontology of each community. Thus, the reasons for inclusion or exclusion are often contingent on the very functioning of society itself. Within his categorization, several cases of exclusion stand out in accordance with different reasons and periods. He considers Greek ostracism to be the perfect example of selective and political exclusion, as it was carried out against individuals who may endanger the status quo. Stigmatization would be another mechanism of exclusion of the individual who had a particular characteristic or was a member of a particular group, which would have led to his/her repudiation (Allman Reference Allman2013, 3–5). This category is one of the broadest and most complex, since, following this definition, many cases could be understood as stigmatization: from people suffering from infectious diseases and individuals with certain physical characteristics (e.g. malformationsFootnote 1) to factors that could culturally be a source of rejection.

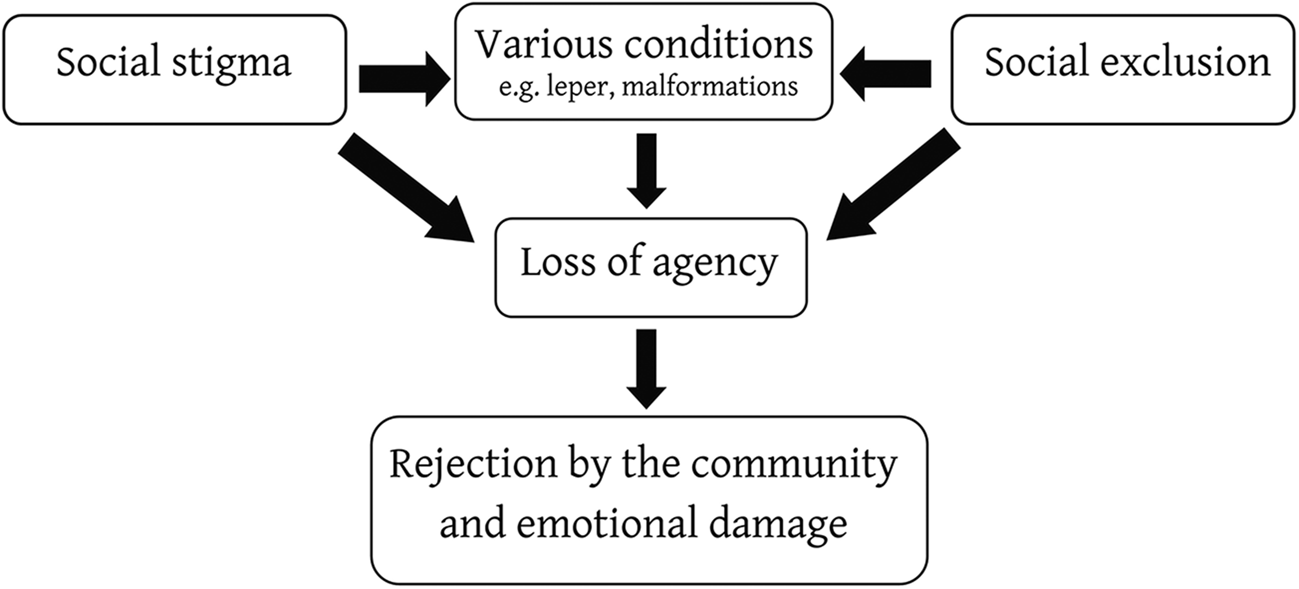

Another approach has been taken from psychology and physiology, whose analyses focus on the consequences that exclusion can have for the person and the group. Following the ‘belongingness thesis’, Baumeister and Leary (Reference Baumeister and Leary1995, 498–500) have argued that the need for identification and belonging to a social group is one of the main motivations of the individual, as it requires frequent interactions and social relations that allow the creation of bonds and affective stability. For this reason, expulsion from the community or self-exclusion can lead to extreme pain and marginalization (Fig. 2) (Baumeister & Dewall Reference Baumeister, Dewall, Williams, Forgas and von Hippel2005, 53–6).

Figure 2. Mechanisms and social consequences of social exclusion. (Adapted and modified from Sekarningrum et al. Reference Sekarningrum, Mujljadji and Yunita2017, 392.)

Sources

The main sources of evidence for the study of social exclusion in ancient Egypt lie in texts, iconography and archaeology. However, they present problems arising from their uneven distribution over time and for belonging mainly to high-culture contexts, tending to be ascribed to the cultural canon and social prototypes, with a very strict decorum.Footnote 2 In this sense, their categorization as ‘cultural artefacts’ (Bloxam & Shaw Reference Bloxam, Shaw, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 17), imbued with socio-cultural codes, has tended to be ignored. A precise study should consider their issuers, their receivers, their functions and the codes that construct them.

First of all, textual evidence has received the most Egyptological attention, although usually making an uncritical study of some examples (e.g. the Satire of the Trades: Burkard & Thissen Reference Burkard and Thissen2015Footnote 5, 183–91). Therefore, it should be properly contextualized and considered among the rest of the data (Grajetzki Reference Grajetzki and Wendrich2010, 183–4; Quirke Reference Quirke2004, 121–6).

Iconography, also linked to the canon (Baines Reference Baines2007, 302–5), only presents a few examples useful for this study, such as human depictions on tomb walls and stelae from several periods. Through an emic approach, this source might provide insight into some aspects of non-canonical culture, but it is still a complicated task (Nyord Reference Nyord2020, 76–7; Silverman Reference Silverman and Redford2001).

Finally, the archaeological evidence allows interpretations to be made in a scientific way which, in the case of Egyptology, lacks a better structured theoretical framework (Bloxam & Shaw Reference Bloxam, Shaw, Shaw and Bloxam2020, 8). Social exclusion can mainly be considered in two domains: human remains and architecture. For the former, there is some evidence of individuals showing signs of illness, mutilation and punishment. In the latter, some examples are paradigmatic in the analysis of social relations from an archaeological point of view: the sites of Heit el-Gurob for the Old Kingdom, Lahun for the Middle Kingdom and Deir el-Medina and Amarna for the New Kingdom. Both Deir el-Medina and Amarna show a very good state of preservation of housing structures, and the second also exhibits a funerary register of individuals belonging to all social strata (Grajetzki Reference Grajetzki and Wendrich2010, 186–7). However, all these cases are a ‘snapshot’, with the advantage of preserving elements that are usually lost (such as the burials of the poorest individuals) (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Stevens, Dabbs, Zabecki and Rose2013), but the disadvantage of not being able to determine whether these finds are normal or exceptional.

The Egyptian worldview: the role of maat

As members of a traditional society, ancient Egyptians did not have a sphere such as philosophy that attempted to provide answers to logical, political or cosmic phenomena, since religion offered most answers to these questions (e.g. Diamond Reference Diamond2015, 401–3; Quirke Reference Quirke2015). In this sense, the notion of maat stands out, usually understood as equivalent to concepts such as order, justice, and truth (Assmann Reference Assmann2010, 12). It can be defined as the principle on whose maintenance order depends, being the antithesis of disorder (represented by isfet). Furthermore, some Egyptologists consider that the purpose of maat is to structure reality in the spheres of the sacred, the cosmos, the state, the society and the individual (Assmann Reference Assmann2010, 148–50). However, maat also provides an example of the ancient Egyptian conception of morality or ethics (Karenga Reference Karenga2004, 3). Its preservation was the main duty of the monarch, since the Old Kingdom allusions to establishing maat by him are frequent. For example, in some instances of the Pyramid Texts (e.g. spells 249, §265c, and 573, §§1483a–c) the deceased king establishes maat and lives by it (Allen Reference Allen2015Footnote 2, 45, 184). Moreover, its maintenance was also the responsibility of the whole of society, since several ethical principles made the person ‘live in the maat’ (Menu Reference Menu2005, 19–27; Moreno García & Pines Reference Moreno García and Pines2020, 230–39), being a topos in the Egyptian officials’ autobiographies of that period and later (Kloth Reference Kloth2002, 221–3; Lichtheim Reference Lichtheim1992, 9–20). Since not only the king and elite members should maintain maat, the cases of individuals that did not live by it should be analysed, since they could suffer social exclusion for endangering the social order and the harmony of the cosmos which is promoted in the biased sources emanatimg from the ‘high culture’ (Moreno García & Pines Reference Moreno García and Pines2020, 239).

Social models and countermodels

Fischer-Elfert (Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 15) considers that the cases he studies as examples of social exclusion and marginalization are probably due to their non-integration into the social fabric as certain elements made some people operate on the margins of maat, moving to other spheres of reality. Likewise, society's role towards these individuals would have moved away from ethics causing their stigmatization (Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 27). However, this author has not analysed the role of these characters in relation to maat.

Since textual information, as the majority of the available evidence, tends to reproduce the bias of the elite (Baines Reference Baines2013), several texts show examples of what can be considered countermodels or counter-prototypical behaviours (Hogg Reference Hogg, Williams, Forgas and von Hippel2005, 245). Some prominent statements are found in the Admonitions of Ipuwer (pLeiden I 344 rto), composed in the Middle Kingdom and known from a Ramesside manuscript. There, it is said that ‘the poor have become rich’ (2.4) or that ‘one cannot distinguish the rich from the man who has nothing’Footnote 3 (4.1) (Enmarch Reference Enmarch2005; Martín Rosell Reference Martín Rosell2014, 132–3, translated). Its importance here lies in its vision of chaos, highlighting the opposed conceptualization of the poor and the rich. Similarly, the Instruction for Merykara, written in the Middle Kingdom and copied at least up to the New Kingdom (Burkard & Thissen Reference Burkard and Thissen2015Footnote 5, 109–15), in clarification of the role of maat in cases of marginalized people, remarks that ‘vagabonds (šwꜢw) cannot speak according to their maat’ (§9) (Quirke Reference Quirke2004, 114). Karenga (Reference Karenga2004, 61) suggests that its context seems to indicate that a poor person would not be able to speak freely because of being subordinated to superior individuals. This also appears in another passage: ‘whoever says “Would that I had!” cannot be righteous; he takes the side of his favourite and positions with the owner of payments’ (§§42–4) (Karenga Reference Karenga2004, 61). Although this text clearly intends to maintain the social hierarchy, it is noteworthy that the lack of maat is marked in socially marginalized people (Assmann Reference Assmann2010, 21–3).

One of the best-known countermodels in ancient Egyptian society is that of the foreigner (ḫꜢstj). The Egyptian worldview, according to a pattern of dualities—opposing or complementary—favoured a conceptualization of the foreigner as someone external to order and belonging to the realm of chaos, as external agents and outsiders to the maat (Riggs & Baines Reference Riggs, Baines, Frood and Wendrich2012, 3–7; Servajean Reference Servajean, Frood and Wendrich2008; Smith Reference Smith and Wilkinson2007, 221–9). That notion was shaped by a cosmovision that was ethnically based on cultural and habitus terms (Dornan Reference Dornan2002, 305–7; cf. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984). This cannot be understood as xenophobia, however, since the residence of foreigners in Egypt was usual, and in some cases promoted, if they adapted to Egyptian customs, ceasing to be conceived of as foreigners in a full sense and being able to integrate and become a part of the elite (Kemp Reference Kemp2018Footnote 3, 24–38; Schneider Reference Schneider and Wendrich2010, 143–8).

Study case 1: disease as a cause of social exclusion

Several sociological studies have brought to light disease and its avoidance as a widespread cause of stigmatization and social exclusion (e.g. Leary & Cottrell Reference Leary, Cottrell and DeWall2013, 11–12; Major & Eccleston Reference Major, Eccleston, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005, 67–70; Mason-Whitehead & Mason Reference Mason-Whitehead, Mason, Abrams, Christian and Gordon2007). The study of disease in ancient Egypt is complex and relies mainly on three types of sources. Firstly, the Egyptian environment and the practice of mummification have favoured the preservation of human remains. Secondly, there are some depictions of several kinds of disease, especially malformations, but decorum prevented the inclusion of reliable details.Footnote 4 Finally, medical papyri help identify and understand symptoms and remedies for some diseases, even though they tend to focus on providing a cure. While there are many documented diseases and illnesses (Nunn Reference Nunn and Redford2001, 397–401), this section will discuss those that might have led to social exclusion.

Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases have been a common factor in the exclusion and stigmatization of individuals affected throughout history (Foucault Reference Foucault1995, 197–200; Leary & Cottrell Reference Leary, Cottrell and DeWall2013, 12; Major & Eccleston Reference Major, Eccleston, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005, 69). In the ancient Egyptian evidence, several texts mention pests/plagues (jꜢdt), but it is not known exactly to which type of disease they correspond. It might refer to one of a recurrent nature, as it appears in a Ptolemaic manual for priests of the goddess of plagues, Sekhmet (pFlorence I.73 + pCarlsberg 463 A.13: Osing & Rosati Reference Osing and Rosati1998, 189–215). On the other hand, it could be one that is widespread throughout the country, but not of a periodic nature, such as that alluded to in the Admonitions of Ipuwer (2.5–6). Besides, plagues mentioned in the Old Testament Book of Exodus are very poorly documented, although in recent decades their origin has been traced back to the Pharaonic period. Thus, some studies have investigated whether bubonic plague could have occurred in Egyptian antiquity (David Reference David, Creasman and Wilkinson2017, 273–5; Panagiotakopulu Reference Panagiotakopulu2004, 269–73). Furthermore, malaria and tuberculosis are included among the plagues that are widely known in ancient Egypt. The former is mentioned by Herodotus (2.125) and attested in some mummies (David Reference David, Creasman and Wilkinson2017, 275–6; Filer Reference Filer1995, 81), whereas the latter is documented by representations and human remains from Predynastic to Roman times (Filer Reference Filer1995, 67–70). Several scholars have traced their appearance back to c. 3500 bce, considering the impact they had on the population (Zink et al. Reference Zink, Molnár, Motamedi, Pálfy, Marcsik and Nerlich2007, 385). At Amarna, archaeological evidence suggests the existence of some epidemic or disease that led to the sudden death of many people. Some Egyptologists place it in the twelfth year of Akhenaten's reign (c. 1326 bce), coinciding with the ceremony of bringing in foreign delegations to which, among others, the Hittites came, who some years later suffered one of the worst epidemics of antiquity (Dodson Reference Dodson2018, 17–18). Among the possible diseases behind this event were malaria and bubonic plague, of which various traces have been found at Amarna (Gestoso Singer Reference Gestoso Singer2017, 237–9; Panagiotakopulu Reference Panagiotakopulu2004, 269). However, none of these examples seems to show evidence of exclusion.

On the other hand, a common response to infectious diseases with a high capacity for contagion seems to have been the physical separation of the sick,Footnote 5 leading to their marginalization and social exclusion (Sekarningrum et al. Reference Sekarningrum, Mujljadji and Yunita2017, 389–92). One of the most significant infectious diseases is leprosy, which seems to have implied separation and exclusion in different periods and cultures (e.g. Boeckl Reference Boeckl2011, 45–62; Demaitre Reference Demaitre2007). Early scholars placed it in Upper Egypt in Ptolemaic and Roman times, although others consider that there is evidence of this infection (probably designated as sbḥ or ḥmwt-sꜢ) as early as the Middle Kingdom (Browne Reference Browne1980, 531; Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 46–54, 58–63). One probable example is a group of four men buried in the Ptolemaic cemetery of Balat (Dakhla oasis) who show symptoms of leprosy. The palaeopathological study carried out by Dzierzykray-Rogalski (Reference Dzierzykray-Rogalski1980) pointed to an Alexandrian origin of these individuals since their physical characteristics seemed to be ‘European’, differing from the rest of the people buried in that cemetery. This could mean that they were expelled from their city of origin, following a common pattern of behaviour with this disease, and were kept apart from society (David Reference David, Creasman and Wilkinson2017, 279–80; Filer Reference Filer1995, 72–4).

Illness as divine punishment

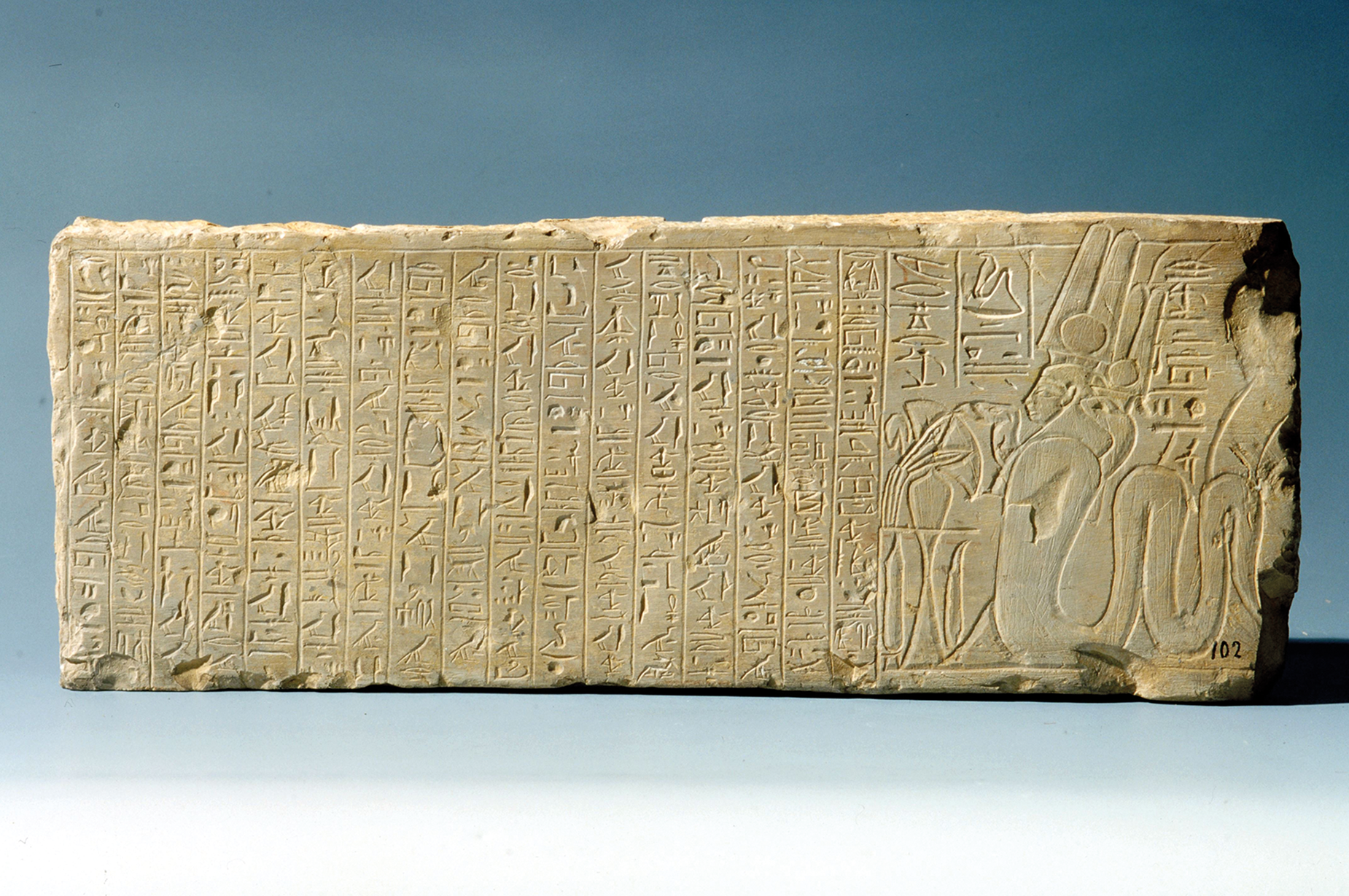

Some societies conceive of illness as punishment for a sin or fault against deities or moral standards (e.g. Bhayro & Rider Reference Bhayro and Rider2017). In ancient Egypt, at least since the New Kingdom, illness (mr) was usually conceptualized as divine punishment (from Sekhmet or Osiris) and associated with certain demons (Beck Reference Beck2018; Galán Allué Reference Galán Allué1999, 18–19; Lucarelli Reference Lucarelli, Bhayro and Rider2017, 58–60). Furthermore, in the ‘penitential hymns’ of Deir el-Medina (Galán Allué Reference Galán Allué1999, 18–25), illness is shown as a reaction to behaviours distant from the social and moral principles of maat. For instance, on the Ramesside Neferabu's stelae the punishing deities are the goddess Meretseger (Turin CGT 50058) (Fig. 3) and the god Ptah (BM EA 589), who caused him ‘to be like street dogs’ and ‘people and gods to look’ on him, ‘just like a man who has committed abomination against his lord’ (E.F. Wente apud Simpson Reference Simpson2003, 284–8).

Figure 3. Neferabu stela (Turin CGT 50058) depicting Meretseger. (Museo Egizio Torino CC BY 2.0 IT.)

Malformations

Disfigurements and malformations are common causes of social stigma and exclusion (e.g. Goffman Reference Goffman1963, 4, 91–2; Major & Eccleston Reference Major, Eccleston, Abrams, Hogg and Marques2005; Oaten et al. Reference Oaten, Stevenson and Case2009). For ancient Egypt, although individuals born with malformations or deformity-causing diseases are rare in the iconographic and textual records, their occurrence is very significant. Besides leprosy, the main documented diseases of this type are dwarfism, poliomyelitis, clubfoot and cleft lip or palate, since they imply various physical defects (David Reference David, Creasman and Wilkinson2017, 276; Robinson Reference Robinson2017, 12–17). Jeffreys and Tait (Reference Jeffreys, Tait and Hubert2000) and Zakrzewski (Reference Zakrzewski, Metcalfe, Cockitt and David2014) deny the existence of marginalization of malformed individuals. However, in chapter 25 of the Teachings of Amenemope (Burkard & Thissen Reference Burkard and Thissen2008, 108–23; Lange Reference Lange1925, 119–20), dated to the Ramesside period and with examples from the Late Period, young men are instructed to avoid laughing at or abusing this group of people, suggesting that this was a known and possibly common behaviour.

It seems not correct to assert that there was generalized discrimination against individuals with certain physical conditions. The cases of dwarfs and blind harpists are unique (Robinson Reference Robinson2017, 12–15; Verbovsek Reference Verbovsek, Wimmer and Gafus2014, 438–40). Dwarfs appear in some myths and could have a prominent role within the social elite, sometimes acquiring a very high social place in it (Dasen Reference Dasen1993). However, these cases do not reflect a generalized phenomenon that can be extrapolated to all individuals with these characteristics, but only to specific instances related to the elite.

Female conditions

Two of the physical conditions associated with women are childbirth and menstruation. As in many traditional societies, the former appears to have been a rite of passage that did not entail greater exclusion than necessary during childbirth and postpartum (Diamond Reference Diamond2015, 210–11). In the case of menstruation, however, an exclusion that was at least physical and temporal seems probable, as it has been a frequent cause of the stigmatization of women (Johnston-Robledo & Chrisler Reference Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler2013).

In ancient Egypt, menstruation was considered ‘taboo’ (bwt). Within ideals of purity, fertility and procreation, menstruation was seen as a counter-model, representing uncleanliness and lack of life as an impure and mundane process (Douglas Reference Douglas2001, 177; Frandsen Reference Frandsen2007, 81–6, 104–5). A Ramesside ostracon from Deir el-Medina (OIM 13512) refers to women in the ‘place of women during menstruation’ (st-ḥmwt jw=w m ḥsmnt), and several later demotic papyri (pLouvre 2424, pLouvre 2431, pLouvre 2443) record the obligation to menstruate (ḥsmn) in the ‘place of women’ (s(t)-ḥmt). This phenomenon is not yet attested by archaeological evidence, but in the case of Deir el-Medina, this space would be outside the city, since a departure from it and the existence of three walls are mentioned (Wilfong Reference Wilfong, Teeter and Larson1999, 421–2). The lack of documentation of the practice of separating women during menstruation and, perhaps, childbirth does not imply that it was not common (Wilfong Reference Wilfong, Teeter and Larson1999, 428–9). Likewise, male relatives of menstruating women were to avoid working in tombs for the fear of contaminating those pure spaces (Pehal & Preininger Svobodová Reference Pehal and Preininger Svobodová2018, 116).

Mental conditions

Mental illnesses and psychological and psychiatric disorders have frequently been a cause of social stigma and exclusion (e.g. Goffman Reference Goffman1963, 4 and passim; Rössler Reference Rössler2016). They are poorly recognized in ancient Egyptian evidence. However, although the most common psychological problems may be related to present-day societies, perhaps some of them were also present in antiquity.

This question has hardly been addressed by Egyptology since it is quite difficult to recognize these phenomena in ancient Egyptian archaeological record and many terms in the texts are difficult to interpret. For example, the so-called ‘hysteria’ has been associated with symptoms of the menstrual cycle (Okasha & Okasha Reference Okasha and Okasha2000, 418–19), although the physical and nervous aspect is barely alluded to. Furthermore, other scholars have associated it with diseases such as blindness or headache (Nasser Reference Nasser1987, 421).

There is evidence of people suffering from moments of extreme sadness and depression. For example, in the second part of the demotic Tale of the Magician Setne (pBM EA 10822), composed in the Late Period but known from a Roman example, a passage (3.5–10) can be understood in this sense: ‘[She] stretched out her hand inside his clothes. She found no warmth. He lay inert in his clothes (…) [She said]: “Sickness and pain are in your heart”’ (R.K. Ritner apud Simpson Reference Simpson2003, 499). Moreover, the most debated text has been the Dialogue of a man with his ba (pBerlin 3024 + pAmherst III + pMallorca I–II), from the Middle Kingdom. In this debate, the former desires death and the latter refutes him. The man explains what death means to him:

Today, death is before me like a sick man being cured, like going out into the street after mourning (…) like the flow of the flood, like a man returning home after an expedition (…) like the open sky (…) like a man longing to see his home when he has spent many years in captivity. (pBerlin 3024 130, 131, 141 & 142: Allen Reference Allen2011, 177)

The man seems to find himself socially isolated, in his own words, ‘for my situation of need has become heavy and there is no one to stand up for me’ (pBerlin 3024 28–9: Allen Reference Allen2011, 167). Thus, he wishes to be judged by the gods in the afterlife. To this would be added a possible exclusion. This is expressed by the metaphor of bad smell (‘Look, my name stinks more than the smell of carrion on harvest days when the sky is hot (…) more than the smell of an eel trap on a fishing day when the sky is hot (…) more than a married woman about whom the lie of a lover has been told’) (pBerlin 3024 86, 98 and 99: Allen Reference Allen2011, 173), and saying that he has no one by his side (‘To whom can I speak today? The brothers have become evil, and today's friends do not love’) (pBerlin 3024 104: Allen Reference Allen2011, 175). Moreover, the possibility of talking to the ba has been interpreted as a suicide attempt, a coma, or a nervous depression (Escolano Poveda Reference Escolano Poveda2017, 36–7; Renaud Reference Renaud1991; Thomas Reference Thomas1980, 285), while the function and context of the text have been attributed to multiple factors and motivations. Some interpretations have only highlighted its poetic and aesthetic aspect, while others considered that it might reflect the relationship between the living and the dead or a state of neurosis and self-therapy (Allen Reference Allen2011, 1–2).

Mental disorders could also be the consequence and not the cause of social exclusion. This can entail mental health effects that may lead to actions such as suicide. If one takes the Dialogue of a man with his ba as a possible case of exclusion, both the possibility that the man was ill and that he was in a depressive process are not incompatible. This has not been considered before, as only single causal hypotheses have been put forward so far. In that sense, exclusion in response to conditions such as physical illness could lead to poor mental health resulting in a risk factor for suicide (Thapa & Kumar Reference Thapa and Kumar2015; Yur'yev et al. Reference Yur'yev, Värnik, Sisask, Leppik, Lumiste and Värnik2011, 234–6).

Study case 2: criminals as excluded individuals

Scholarship has shown the complex relations between crime and social exclusion (e.g. Hale & FitzGerald Reference Hale, FitzGerald, Abrams, Christian and Gordon2007). Leaving aside social exclusion as a cause of criminality, the latter and its punishment seem to have been a recurrent and constant factor in the stigmatization and exclusion of individuals and their families (e.g. Foucault Reference Foucault1995, 272; Goffman Reference Goffman1963, 4; Murray Reference Murray2007).

Main punishments

Behaviours against the community or straying from social conventions could be punished in different ways. So far, no legislation has been found that would allow us to know how the law worked in ancient Egypt. Therefore, the main sources are data about the ‘Great Prison’ from the Middle Kingdom, temple decrees (e.g. Horemheb's Decree: Kruchten Reference Kruchten1981) and court records from the New Kingdom (McDowell Reference McDowell and Redford2001).

The application of justice depended on several factors and was not always effective. Assmann (Reference Assmann1992, 150–51) thinks that it followed a scheme of causality that depended on the intervention of society or the state. Additionally, other forms of punishment were applied, as the society and the state were substituted by metaphysical agents and methods, such as gods, demons, or curses.

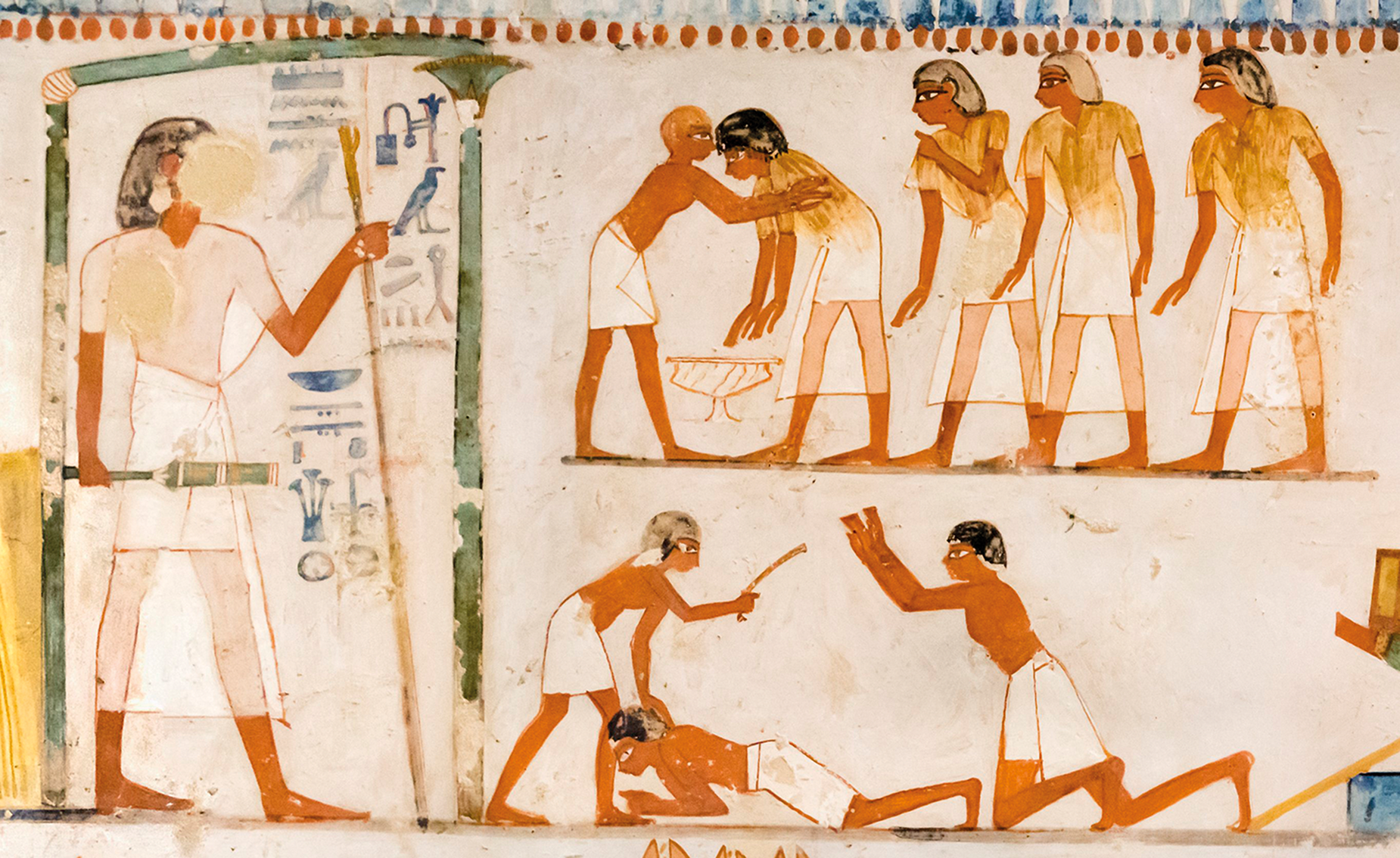

Among the best-known crimes were treason, lèse-majesté, desertion, murder, abuse, adultery, rape and robbery. All of them had different penalties, depending on the individuals involved and their degrees, which were usually determined in trials including various prestigious officials and personalities (Lippert Reference Lippert, Frood and Wendrich2012, 2; Müller-Wollermann Reference Müller-Wollermann2015, 228–33). Punishments varied according to the social status of the condemned individual: physical punishment was not as common for members of the elite as it was for the rest of the Egyptians (Fig. 4). The death penalty and the use of violence are remarkable for their marked rituality (Muhlestein Reference Muhlestein2015, 246–8), as shown by the iconographic motif of the ‘smiting of the enemy’, in which the king strikes prostrate enemies with a mace, highlighting the maintenance of order over chaos (Bestock Reference Bestock2018, 193–7, with references). However, the death of the enemy, usually characterized as a foreigner, cannot be ascribed to ancient Egypt's internal justice system. Deaths as a result of trials included skinning (rarely used, mainly ritual), decapitation (used in various cases), impalement (usually for temple robbery) and burning (in extreme cases, since destroying the body meant losing the possibility of reaching the afterlife) (Leahy Reference Leahy1984, 199–202; Muhlestein Reference Muhlestein2015, 245–7; Willems Reference Willems1990, 28–33). It should be noted that these punishments expel or distance the individual from society, and even from the afterlife, in a way similar to execration rites and damnatio memoriae (Bochi Reference Bochi1999). In this sense, the Turin Judicial Papyrus (De Buck Reference De Buck1937; Kitchen Reference Kitchen2008, 297–305), recording the legal process that followed the murder of Ramesses III, recounts that some of the perpetrators were forced to commit suicide. Moreover, the ‘anonymous mummy E’, a son of that monarch possibly involved in the plot, was ritually excluded from a dignified afterlife by being buried with both hands tied, without mummification (nor his name inscribed) and wrapped in ovicaprid skins (Borrego Gallardo Reference Borrego Gallardo, Fernandez de Mier and Cortés Martín2016, 77, with references).

Figure 4. Peasant punished in the presence of his master, from the tomb of Menna (Theban Tomb no. 69). (Modified from kairoinfo4u, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 [Flickr].)

These punishments probably involved social exclusion, not as the initial motivation but rather as a consequence of them. Moreover, there are cases where social exclusion could be a motivation in trials for those individuals sent to work camps or prisons, those who suffered physical mutilation to evidence their guilt, or the exiled and fugitives.

Prisons and work camps

The decorum regulating the textual and artistic records and the scarcity of administrative documents complicate the investigation of institutions like prisons or enforced labour camps. If we adopt modern prisons as a model, it is difficult to find a parallel for ancient Egypt, as the mechanisms of control and punishment respond to different cultural patterns (Foucault Reference Foucault1995). However, some Egyptian institutions might have had similar functions to modern ones.

Three terms may be translated as ‘prison’: ḫnrt, from ḫnr, ‘to control, to repress’; jtḥ(w), from jtḥ, ‘to force, to push someone’; and rtḥ(w), from rtḥ, ‘to repress, to confine’ (Diego Espinel Reference Diego Espinel, Torallas Tovar and Pérez Martín2003, 3–4). Ḫnrt seems to have been the most frequent, and it has commonly been translated as ‘prison’, ‘work camp’ and ‘fortress/enclosure’ (Diego Espinel Reference Diego Espinel, Torallas Tovar and Pérez Martín2003, 3–12; Mazzone Reference Mazzone2017, 22). For instance, in the Papyrus Westcar (7.15–16), dated to the late Middle Kingdom and known from a single copy dated to the Second Intermediate Period, there is mention of a ‘criminal who is in prison (ḫnrt)’ on whom penalties are to be inflicted (Diego Espinel Reference Diego Espinel, Torallas Tovar and Pérez Martín2003, 24; Mazzone Reference Mazzone2017, 35). Similarly, in the scribal miscellany of the Papyrus Lansing, dated to the New Kingdom, it is said of a soldier that ‘if he flees with deserters, all his people are put in a prison (jtḥw)’ (10.7) (Diego Espinel Reference Diego Espinel, Torallas Tovar and Pérez Martín2003, 12–13). Thus, imprisonment seems to be a punishment that could affect any individual and his/her immediate environment.

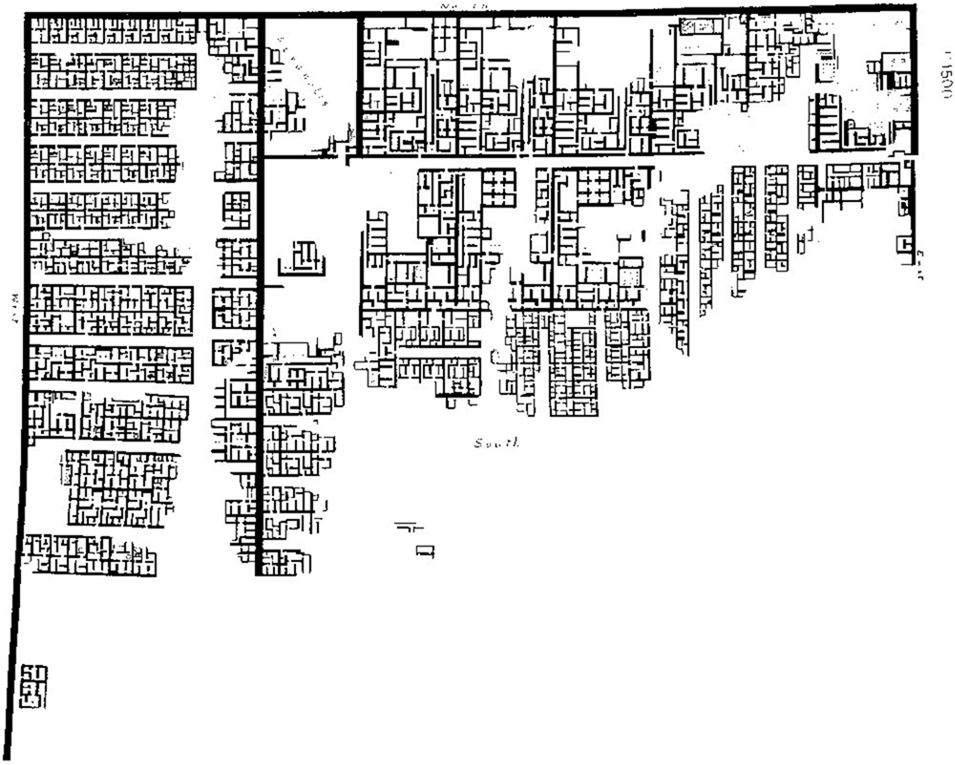

Although imprisonment or confinement are mainly known from textual evidence, these spaces for reclusion, distributed throughout the territory, have been tentatively identified in the archaeological record. One example is the ‘Great Prison’ (Ḫnrt wrt) of Lahun (Fig. 5), which has been identified in the western part of the enclosure (Mazzone Reference Mazzone2017, 24–30, 34–7). Moreover, it has been proposed that the contemporary work camp for agricultural labour at Qasr es-Sagha, an isolated site in the Fayum region, was probably created ‘with a punitive intention’ (Kemp Reference Kemp2018, 227–8, 238–9, fig. 5.18, with references). On the other hand, the case of Heit el-Gurob is a paradigmatic example of control, since the distribution of the houses and streets shows passages and corridors, as well as thick walls, that were meant to control the living population on the site, mainly workers (Lehner & Tavares Reference Lehner, Tavares, Bietak, Czerny and Forstner-Müller2010).

Figure 5. Town plan of Lahun, with the ‘Great Prison’ on the western area. (Adapted from W.M.F. Petrie, copyrighted free use [Wikimedia Commons].)

Permanent mutilations

The main physical punishment with permanent effects on the body was mutilation of the ears and nose. This practice is documented by texts, but not by iconography or human remains. It seems to be a regular practice, mainly documented for the New Kingdom, as the Turin Judicial Papyrus (6.1) shows: ‘persons who were punished by having their noses and ears cut off, for having ignored the instructions they were told’ (Loktionov Reference Loktionov2017, 266–70).

Although it may seem an unusual form of punishment, nasal ablation was common among the Hittites, in the Roman Empire or the medieval Iberian Peninsula, provoking a strong social dislike towards the punished individual (Loktionov Reference Loktionov2017, 268). In ancient Egypt, this practice responded to a person's incapacitation, since if they survived the haemorrhage and possible infections, they would suffer a continuous stigma, useful for the identification of criminals, such as thieves or adulterous women (Orriols i Llonch Reference Orriols i Llonch, Antela-Bernárdez, Zaragozà Serrano and Guimerà Martínez2017, 27). This could cause severe rejection and social and religious exclusion, as it is probable that it would impede ‘pure’ contact with the divinity (Loktionov Reference Loktionov2017, 275–8). For instance, in the Turin Judicial Papyrus (6.2), the steward Pabasa preferred to commit suicide rather than suffer the stigma that this punishment entailed (Borrego Gallardo Reference Borrego Gallardo, Fernandez de Mier and Cortés Martín2016, 71; Muhlestein Reference Muhlestein2011, 59).

Fugitives and exiled individuals

Another type of punishment that could lead to social exclusion is found in individuals who, for various reasons, were fugitives and exiles. The study of forced migration and refugees is quite controversial, since terms such as ‘slavery’ or ‘invasion’ might arise. The first and only monograph on this matter was by Gundlach (Reference Gundlach1994) and, although other scholars have dealt with this aspect, not many have applied a sociological approach to it (Langer Reference Langer2020, 5, with references).

Several sources evidence this phenomenon. Literary texts show a paradigmatic example: the story of Sinuhe, composed in the Middle Kingdom and copied up to the New Kingdom. In it, the protagonist flees Egypt and goes to the Palestinian region after the murder of Amenemhat I. He could only return after the new monarch allowed it (Burkard & Thissen Reference Burkard and Thissen2015Footnote 5, 122–33, with references). This case could be ascribed to a temporary flight and refuge of a political nature (Langer Reference Langer and Langer2017, 44). Since the New Kingdom, forced migrations are much more documented (Langer Reference Langer and Langer2017), as in the Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty between Ramesses II and Hattushili III (c. 1259 bce), which specifies the treatment of refugees (including members of the elite) from both kingdoms. This clause seems to have been a common practice among the great powers of the Late Bronze Age (Liverani Reference Liverani2002). Furthermore, in the Banishment Stela (Louvre C.256) (c. 1054 bce), the return of deported servants from the Kharga oasis is allowed after they have been forgiven by the god Amun-Ra and his high priest Menkheperra (Ritner Reference Ritner2009, 124–8, with references).

Another interesting case is found in divorced women. Although they could be readmitted by their former family, this was not always the case, as they could be expelled from the community and belong to what the sapiential text of the Instructions of Ani, composed in the Ramesside period and copied up to the end of the Third Intermediate Period (Burkard & Thissen Reference Burkard and Thissen2015Footnote 5, 99–108), designates as ‘women from outside’ (st-ḥmt m rwtj) (B 16.13–17). Some scholars have considered these women to be prostitutes, but their situation seems rather to result from divorce (Fischer-Elfert Reference Fischer-Elfert2005, 165–72, 205–8).

These cases represent a quite characteristic phenomenon, since people could be forced to live—temporarily or permanently—away from their homes, leaving their city or even the country. As the text of Sinuhe reveals, this could provoke huge emotional damage, since the protagonist was socially excluded from their family and culture, breaking the relation of belonging with the community.

Discussion and conclusions

Social exclusion understood as the exclusion of individuals who are a risk or against the group (Leary & Cottrell Reference Leary, Cottrell and DeWall2013, 11–12) is a mechanism that has taken different forms throughout historyFootnote 6 and is currently being addressed in terms of equality, humanity and solidarity (Lakin & Chartand Reference Lakin, Chartand and DeWall2013, 267–9). Despite being a recently coined concept, it is legitimate to raise the hypothesis of the existence of social exclusion in ancient Egypt in some of the terms and modalities established by sociology and related social sciences, an approach hitherto unexplored in Egyptology and only occasionally in other societies of antiquity. The application of a sociological framework from an emic perspective to the evidence for ancient Egypt should consider the functioning of Egyptian society in terms of its social models and counter-models and the role played by principles like maat. The sources are not evenly distributed in contexts and over time and have clear elite bias. However, two case studies seem appropriate to test the hypothesis.

First, some diseases involved exclusion for different reasons. Social hygiene was applied to the individuals afflicted by those of an infectious nature, mainly leprosy, establishing a physical separation from them. For its part, malformation, far from the aesthetic canon, provoked mockery and singling out, stigmatization but not exclusion as such. Female conditions such as menstruation involved marginalization and temporary exclusion according to conceptions of pollution within an androcentric society. Finally, mental illnesses or disorders seem to have been conceived as motivated by divine causes or curses for distancing from the social and moral principles of maat. This could cause exclusion and social and religious self-exclusion, breaking with the principle of belongingness and affective stability to the point of reaching extreme situations, such as depression and suicide.

Second, in the case of criminals, the example of exiles and fugitives implied exclusion as a consequence of forced departure, similar to ostracism. However, in some punishments, this intentionality seems clearer. Exclusion or deprivation of the afterlife is common in some punishments, but in life, this phenomenon is seen in prisons (involving physical exclusion) or permanent mutilations. These could entail situations similar to those suffered by the sick, as well as a stigma, rejection and repudiation of the crime committed.

The application of a theoretical framework drawn from the social sciences to the uneven set of ancient Egyptian sources has permitted us to fill some of its gaps and to determine that it is highly probable to affirm the existence of social exclusion in ancient Egypt, at least in the cases that have been analysed. As in other societies, in ancient Egypt, this phenomenon also responded to both practical and idiosyncratic motives, notably the distancing from maat.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Francisco L. Borrego Gallardo for his valuable feedback and encouragement in this research. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their comments that have improved this work.