Introduction

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder, impacting the daily lives of millions around the world [Reference Léger and Bayon1,Reference Morin and Jarrin2]. This disorder is characterized by dissatisfaction with sleep quality or quantity as well as difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep; these sleep complaints cause clinically significant impairment or distress [3]. Individuals with insomnia have lower health-related quality of life and higher healthcare utilization rates, including more emergency department visits, calls to providers, and use of over-the-counter medications [Reference Hatoum, Kong, Kania, Wong and Mendelson4]. In the workplace, adults with insomnia have higher rates of absenteeism and greater difficulties concentrating [Reference Léger, Guilleminault, Bader, Lévy and Paillard5]. Insomnia is also related to high rates of vehicle, workplace, and home accidents [Reference Léger, Bayon and Ohayon6,Reference Shahly, Berglund and Coulouvrat7]. One study estimated that the direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia over a 6-month period exceed $1000 dollars per patient [Reference Ozminkowski, Wang and Walsh8]. Another calculated that the annual cost of insomnia-related workplace accidents and errors in the United States (US) totaled $31.1 billion [Reference Shahly, Berglund and Coulouvrat7].

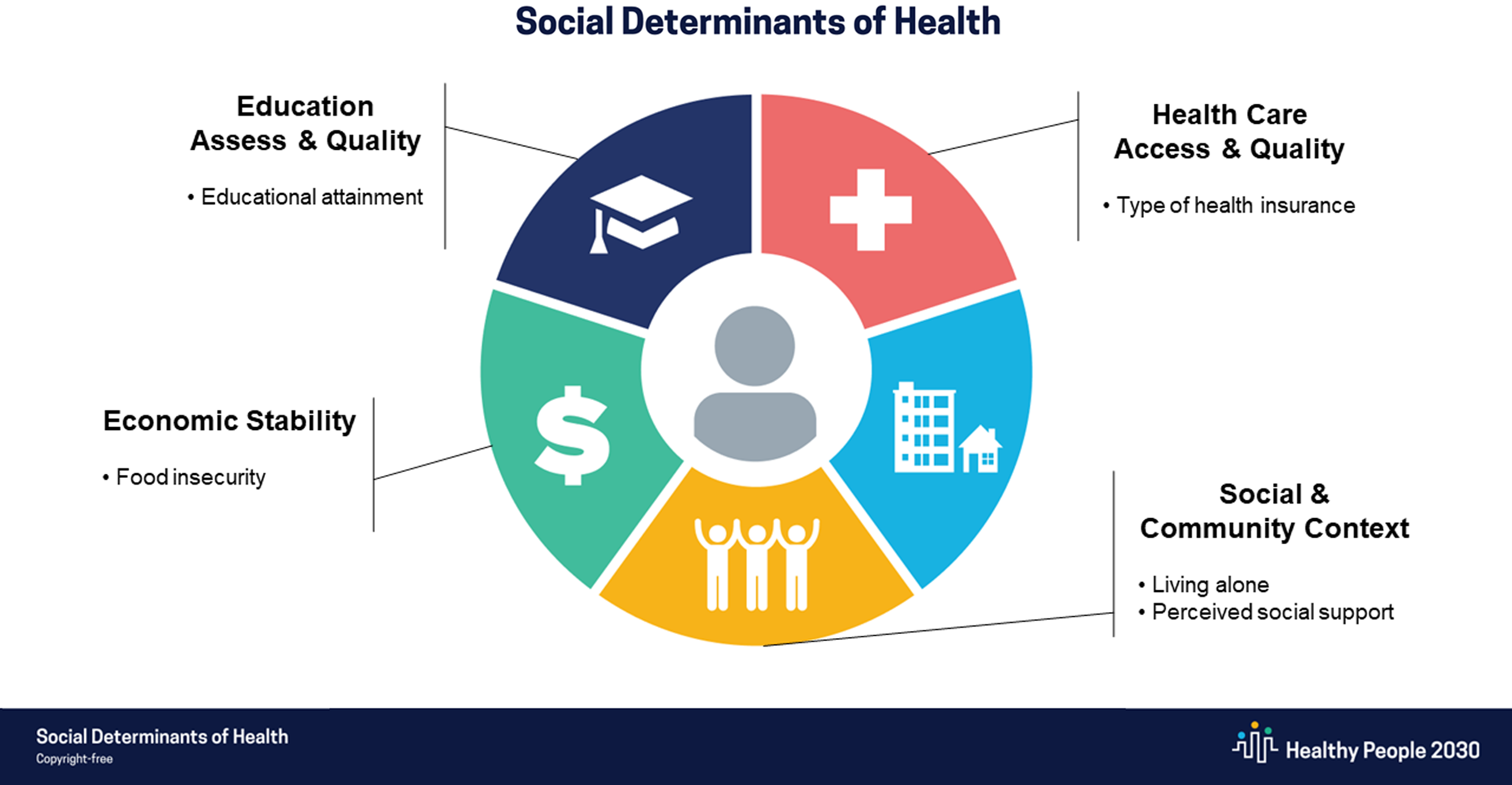

There have been multiple calls to explore the impact of social determinants of health (SDOH) on sleep [Reference Jean-Louis and Grandner9,Reference Jean-Louis, Grandner and Seixas10]. SDOH are the conditions in people’s environments that affect their health and quality of life [11]. Healthy People 2030 identified the following five SDOH domains: economic stability (e.g., food insecurity), education access and quality (e.g., high school graduation), health care access and quality (e.g., inadequate health insurance), neighborhood and built environment (e.g., quality of housing), and social and community context (e.g., social cohesion, discrimination) [11]. Research suggests historically marginalized and socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals experience higher rates of insomnia and other sleep problems [Reference Grandner, Williams, Knutson, Roberts and Jean-Louis12,Reference Grandner, Ruiter Petrov, Rattanaumpawan, Jackson, Platt and Patel13]. Discrimination may be a contributing factor and has been associated with worse sleep outcomes, such as poor sleep quality and shorter sleep duration [Reference Slopen, Lewis and Williams14].

Within the United States, the construct of race is considered a proxy for structural and economic disparities [Reference Buchanan, Perez, Prinstein and Thurston15]. It is well established that Black individuals tend to have significantly shorter sleep durations than non-Hispanic White individuals [Reference Jean-Louis, Grandner and Seixas10,Reference Ahn, Lobo, Logan, Kang, Kwon and Sohn16,Reference Ruiter, DeCoster, Jacobs and Lichstein17]. Although a meta-analysis of nine studies published prior to 2009 suggested White individuals report higher rates of insomnia symptoms than Black or African Americans [Reference Ruiter, DeCoster, Jacobs and Lichstein17], a more recent review indicated mixed findings of self-reported insomnia across Black, Hispanic, and Asian groups when compared to non-Hispanic Whites [Reference Ahn, Lobo, Logan, Kang, Kwon and Sohn16]. Individuals and households with lower educational attainment appear to be at greater risk for insomnia, even after controlling for ethnicity, age, and gender [Reference Gellis, Lichstein and Scarinci18]. Loneliness has also been associated with insomnia and sleep disturbances [Reference Griffin, Williams, Ravyts, Mladen and Rybarczyk19,Reference Hom, Hames and Bodell20]. However, it is unclear to what extent mental health conditions may be influencing this association. There is limited research on insomnia within transgender populations, with a 2020 review finding that only four publications specifically examined sleep among transgender individuals [Reference Butler, McGlinchey and Juster21]. Studies suggest transgender adolescents and college students have higher rates of sleep difficulties, insomnia symptoms, and insomnia diagnoses than their cisgender peers [Reference Levenson, Thoma, Hamilton, Choukas-Bradley and Salk22,Reference Hershner, Jansen, Gavidia, Matlen, Hoban and Dunietz23]. A meta-analysis of over 1.2 million participants found that women had a 1.41 greater risk of developing insomnia than men [Reference Zhang and Wing24]. Insomnia symptoms become more prevalent with age [Reference Brewster, Riegel and Gehrman25,Reference Ohayon26] and veteran status [Reference Soberay, Hanson, Dwyer, Plant and Gutierrez27].

Insomnia is frequently comorbid with physical and mental health disorders. Within the past decade, there has been an increased effort to examine relationships between cardiometabolic disease and insomnia; the American Heart Association recently added sleep health as the eighth and newest component of cardiovascular health [Reference Lloyd-Jones, Allen and Anderson28]. One review provided support for increased rates of hypertension, coronary heart disease, and heart failure among those with insomnia [Reference Javaheri and Redline29]. Suboptimal sleep was associated with history of heart disease [Reference Williams, Grandner and Wallace30] and cardiometabolic diseases, which include obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [Reference Rangaraj and Knutson31]. Insomnia is also highly comorbid with mental health disorders, including anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [Reference Griffin, Williams, Ravyts, Mladen and Rybarczyk19,Reference Hom, Hames and Bodell20,Reference Bragantini, Sivertsen, Gehrman, Lydersen and Güzey32–Reference Wynchank, Bijlenga, Beekman, Kooij and Penninx34].

There is a crucial need to better understand who is at-risk for developing insomnia, given the substantial public health burden [Reference Morin and Jarrin2,Reference Hatoum, Kong, Kania, Wong and Mendelson4–Reference Ozminkowski, Wang and Walsh8]. This project is responsive to the recent call to address sleep health disparities and better understand the role of sociocultural contributors to sleep health [Reference Jackson, Walker, Brown, Das and Jones35]. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the extent to which insomnia is related to demographics, social determinants of health, and other physical and mental health conditions among a community sample in Florida. More specifically, this project aimed to (1) identify associations between demographic variables, health conditions and a reported history of insomnia and (2) determine whether individuals with lower social support are more likely to endorse insomnia than those with higher social support while controlling for mental and physical health conditions. As an extension of our prior work [Reference Serdarevic, Osborne, Striley and Cottler36], the current project includes an additional 3500 participants and has a novel focus on the impact of social support. We hypothesized that females, older adults, and individuals of historically marginalized races would be more likely to report insomnia. We also expected that individuals with lower levels of educational attainment, who experienced food insecurity, do not have health insurance, previously served in the armed forces, had a cardiometabolic disease, anxiety, depression, or ADHD, and had lower social support would be more likely to report insomnia versus their counterparts.

Methods

Participants

Participants included members of HealthStreet, a community outreach program at the University of Florida (UF) that aims to reduce disparities in healthcare and research through community and other stakeholder engagement. Community health workers (CHWs) approached individuals at locations within their communities, such as grocery stores, laundromats, and libraries. CHWs conducted health assessments using the Health Needs Assessment, which took approximately 20 minutes. Assessed domains broadly included demographics, views about research, mental and physical health conditions, healthcare utilization, and substance use. Based on the participant’s responses, CHWs linked community members with existing research opportunities at UF as well as any needed community medical and social services. For the purposes of this study, we limited participants to those 18 years of age and older. The protocol was approved by the Human Studies Committee of UF. Participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection occurred between 2011 and 2021, continuing throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. HealthStreet was granted essential research exemption by the Institutional Review Board to continue research activities during the pandemic. HealthStreet engaged the community by providing COVID-19 testing, food distribution, clothing and toiletries, and Narcan nasal sprays for opioid overdose prevention. Due to restrictions surrounding in-person research activities, HealthStreet switched to conducting virtual informed consent and health needs assessments through Zoom. Pandemic and virtual community engagement affected data collection during 2020 and 2021. Prior to the pandemic (2011–2019), assessments averaged 1303 per year. The annual number of assessments declined to 263 in 2020 and 526 in 2021.

Figure 1. Measures within context of Healthy People 2030’s SDOH framework. CHW = community health worker.

Figure 2. Participant flow diagram. CHW = community health worker.

Measures

Insomnia

History of insomnia was measured via participant self-report with the question: “have you ever been told you had, or have you ever had a problem with insomnia?” Positive endorsement of this question indicated a reported history of insomnia, which is consistent with prior epidemiological research [Reference Olfson, Wall, Liu, Morin and Blanco37].

Demographics

Participants reported their age, gender, and race. Age was dichotomized into younger adults (aged 18–64) and older adults (65 years and older). We classified individuals above the age of 65 as older adults due to the typical vocational and lifestyle transitions that occur around the traditional retirement age. Educational attainment was measured by total years of education, excluding kindergarten or preschool. Health insurance was measured categorically; options included whether an individual had private insurance, Medicare/Medicaid, or no insurance. Food insecurity was assessed via the question “have there been times in the last 12 months when you did not have enough money to buy food that you or your family needed?” Participants also reported whether they ever served in the armed forces.

Physical and mental health conditions

Reported history of anxiety, ADHD, depression, and cardiometabolic disease were assessed using a similar question stem. Participants were asked “have you ever been told you had, or have you ever had a problem with [health condition]? Cardiometabolic disease was indicated by endorsement of: arrhythmias, chest pain, coronary artery disease, heart attack, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or type II diabetes.

Social support

Participants reported the number of people living in their home; we classified participants into two groups: those who lived alone and those who lived with others. We measured perceived social support via three items using a five-point Likert scale, where one equaled strongly disagree and five equaled strongly agree. The items included: “There is a person I can talk to about things that are important to me. There is a person I can rely on for practical things like doing favors for me. In general, I am satisfied with the support I receive from people in my life.” The three items were strongly correlated (r range of 0.64–0.68) and had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). Consistent with prior work [Reference Emerson, Fortune, Llewellyn and Stancliffe38], we summed scores across the three items and converted this social support scale into a binary predictor of perceived social support. A score of 12 to 15 indicated “higher” perceived social support, given that a 12 corresponded with an average rating of “agree” across items. A score of 3–11 indicated “lower” perceived social support. These items measuring perceived social support were added to the Health Needs Assessment approximately 4 years into the study. Fig. 1 illustrates how our measures map onto Healthy People 2030’s SDOH framework [11].

Analyses

We described the sample demographics using frequency count, mean, and standard deviation (SD). We conducted two binary logistic regressions to examine the amount of variance in reported history of insomnia explained by demographic factors, physical and mental health conditions, and social support. We used block entry of all explanatory variables, meaning all explanatory variables were controlled for, and we did not eliminate any predictors from the models. Model 1 covariates included age, gender, race, education, food insecurity, health insurance, veteran status, cardiometabolic disease, anxiety, depression, ADHD, and living alone. Model 2 consisted of all Model 1 covariates plus perceived social support. We conducted two separate models due to over half of the sample (59.6%) missing the perceived social support measure; those items were added approximately four years into data collection. Model 2 examined the impact of perceived social support on insomnia while controlling for all other covariates and was restricted to individuals with complete data (40.4% of sample). Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to assess the relationships between insomnia and variables of interest. Data analysis was performed using SAS. Results were considered significant at α = 0.05.

Results

Participants

Our sample is comprised of a total of 11,960 community members who completed the Health Needs Assessment; this represents 80% of community members engaged by CHWs (see Fig. 2). Participants ranged from 18 to 94 years of age (M age = 45.55 ± 16.57) and were predominantly female (60%). The sample was comprised of the following racial/ethnic groups: 55% Black/African American, 38% White, 5% Other, 1% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1% Asian. Due to the small number of individuals identifying as Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 21), this group was combined with the “Other” racial group. On average, participants completed 13 years of education. Insomnia was reported by 27.3% of the sample (n = 3,265). Table 1 includes demographic data and the relationship of each variable to reported insomnia through adjusted ORs and their confidence intervals.

Table 1. Relationships between social determinants and insomnia

A Indicates only a portion of sample (4830 out of 11,960) completed this measure.

* Indicates 95% CI does not include 1.00.

Aim 1: Associations Between Insomnia, Demographics, and Health Conditions

Insomnia was reported more by older adults compared to those aged 18–64 years (OR = 1.16, 95% CI [1.001, 1.34]) and females versus males (OR = 1.18, 95% CI [1.04, 1.31]). Rates of insomnia did not significantly differ between transgender individuals or males. Black/African American individuals reported significantly lower rates of insomnia than White individuals (OR = 0.72, 95% CI [0.65, 0.79]). There were no significant differences between other racial/ethnic groups, across education levels, or across types of health insurance. Individuals with food insecurity reported higher rates of insomnia than those with food security (OR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.39, 1.68]). Veterans reported higher rates of insomnia when compared to those who did not serve in the armed forces (OR = 1.30, 95% CI [1.11, 1.51]). Individuals with cardiometabolic disease (OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.44, 1.74]), anxiety (OR = 2.33, 95% CI [2.09, 2.59]), depression (OR = 2.57, 95% CI [2.31, 2.85]), and ADHD (OR = 1.44, 95% CI [1.24, 1.67]) reported higher rates of insomnia than those without these health conditions. Depression had the strongest association with insomnia.

Aim 2: Associations Between Insomnia and Social Support

Individuals who lived alone were more likely to endorse insomnia than those who lived with someone else (OR = 1.14, 95% CI [1.03, 1.27]). Individuals with lower perceived social support were also more likely to endorse insomnia than those with higher perceived social support (OR = 1.24, 95% CI [1.07, 1.45]).

Discussion

Over one-quarter (27.3%) of our sample of community members in Florida reported a history of insomnia, which is consistent with self-reports of sleep difficulties in other community samples [Reference Morin and Jarrin2,Reference Olfson, Wall, Liu, Morin and Blanco37,Reference Kessler, Berglund and Coulouvrat39]. This study makes a substantial contribution to the literature base as it provides additional evidence regarding who is at greater risk for insomnia among a community-based sample. It is also responsive to a recent call to address sleep health disparities by examining multiple domains of influence, including SDOH [Reference Jackson, Walker, Brown, Das and Jones35].

Community members aged 65 years and older reported higher rates of insomnia than their younger counterparts, which is consistent with our hypothesis and a prior review [Reference Patel, Steinberg and Patel40]. It is important to note that healthy adults experience normative age-related changes in their sleep architecture, which may partially contribute to the development of insomnia [Reference Ohayon, Carskadon, Guilleminault and Vitiello41]. More specifically, as adults age, they experience decreases in percentage of REM sleep, total sleep time, and sleep efficiency as well as increases in sleep latency, percentage of stage 1 and stage 2 sleep, and wake after sleep onset [Reference Ohayon, Carskadon, Guilleminault and Vitiello41]. Additionally, retirement is considered a risk factor for insomnia among older adults [Reference Brewster, Riegel and Gehrman25]. It has also been suggested that age-related increases in insomnia may be primarily attributable to age-related increases in physical and mental health disorders [Reference Vitiello, Moe and Prinz42]. Although within our sample, older age remained associated with insomnia after controlling for numerous physical and mental health conditions.

Consistent with prior meta-analyses [Reference Zhang and Wing24], women reported higher rates of insomnia than men within our sample. It is also worth noting that our findings offer a preliminary signal that transgender individuals may experience higher rates of insomnia. Although not statistically significant, transgender individuals appeared to report higher rates of insomnia than men (OR = 1.37, 95% CI [0.62, 3.02]); however, this finding should be considered within the context of a small sample of transgender individuals (n = 31). Given the relative nascency of this literature base [Reference Butler, McGlinchey and Juster21], more research within larger samples of transgender individuals is needed.

Black/African American adults within our sample reported significantly lower rates of insomnia than White adults. These findings contradict recent studies suggesting that Black/African American adults report higher rates of insufficient sleep and poorer sleep quality [Reference Williams, Grandner and Wallace30,Reference Carnethon, De Chavez and Zee43]. Our results add to the mixed findings related to insomnia rates across Black and non-Hispanic White groups [Reference Ahn, Lobo, Logan, Kang, Kwon and Sohn16]. One review suggests that there may be differences in reported insomnia symptoms across races, but not differences in actual insomnia rates [Reference Petrov and Lichstein44]. Additionally, a study found that Black adults were more likely to report having a sleep latency greater than 30 minutes, but less likely to endorse “trouble falling asleep” when compared to White adults [Reference Grandner, Ruiter Petrov, Rattanaumpawan, Jackson, Platt and Patel13]. This discrepancy between two self-reports of sleep onset difficulties highlights the importance of question wording and its potential impact on participants’ responses. Future research should explore how health literacy may impact findings.

The relationship between SDOH and insomnia was mixed within our study, with findings differing based on which domain of SDOH was examined. Individuals with food insecurity reported higher rates of insomnia within our sample, which is consistent with extant literature demonstrating that higher rates of household food insecurity were related to higher sleep latency, difficulties falling asleep, difficulties maintaining sleep, and early morning awakenings [Reference Grandner, Ruiter Petrov, Rattanaumpawan, Jackson, Platt and Patel13]. One review suggests that both biobehavioral and psychological mechanisms may account for the relationship between food insecurity and sleep difficulties [Reference Lee, Deason, Rancourt and Gray45]. For example, the stress associated with food insecurity may negatively impact sleep[Reference Lee, Deason, Rancourt and Gray45]. Additionally, food insecure adults are more likely to have lower quality diets, which have been associated with shorter sleep durations, worse sleep quality, and insomnia [Reference Lee, Deason, Rancourt and Gray45]. However, contrary to previous research [Reference Grandner, Ruiter Petrov, Rattanaumpawan, Jackson, Platt and Patel13,Reference Gellis, Lichstein and Scarinci18], we did not find any differences in insomnia based on educational attainment or health insurance status. The possibility exists our lack of significant findings may be partially attributable to different categorizations of educational attainment and health insurance.

Adults who live alone and who have lower levels of perceived social support reported higher rates of insomnia. These findings further support prior work demonstrating that loneliness is related to both insomnia and sleep disturbances [Reference Griffin, Williams, Ravyts, Mladen and Rybarczyk19,Reference Hom, Hames and Bodell20]. Living alone is considered a measure of objective social isolation, whereas perceived social support is related to perceived social isolation, which is commonly referred to as loneliness [Reference Cacioppo and Cacioppo46]. It has been proposed that depression may account for the relationship between loneliness and insomnia [Reference Hom, Hames and Bodell20]. However, within our sample, the association between social support and insomnia remained even after controlling for depression and anxiety. Although we acknowledge that mental health and social factors are intertwined, we suggest social isolation be considered a separate precipitating or perpetuating factor in the development and maintenance of insomnia. More longitudinal research is needed to better understand relationships between living alone, perceived social support, and the experience of insomnia. There is a need for interventions targeting loneliness, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. One recent review suggests that mindfulness-based interventions, weekly Tai Chi classes, visual arts discussions, and laughter therapy have demonstrated significant improvements in loneliness and social support [Reference Williams, Townson and Kapur47]. Other promising approaches included educational lessons (e.g., addressing barriers to social integration, making friends) and interventions that facilitated interactions between peers [Reference Williams, Townson and Kapur47]. Although our work cannot establish any causal relationship between social isolation and insomnia, it raises important questions about whether these loneliness interventions may indirectly improve some aspects of sleep.

Consistent with prior research [Reference Soberay, Hanson, Dwyer, Plant and Gutierrez27], military veterans had higher rates of insomnia when compared to civilians. Integrated theoretical models have been developed to illustrate the cyclical nature of insomnia among military veterans in the USA. These models demonstrate how precipitating factors, such as a prior trauma history, can be perpetuated by stressful events (e.g., military-related deployment or re-integration), which can lead to a stress response and the development of insomnia [Reference Hughes, Ulmer, Gierisch, Nicole Hastings and Howard48]. Although deployments have been linked to significant sleep disturbances [Reference Peterson, Goodie, Satterfield and Brim49], one study found individuals on active duty had lower rates of insomnia than both veterans and civilians [Reference Soberay, Hanson, Dwyer, Plant and Gutierrez27]. It is also important to note that insomnia has been associated with a greater risk of suicidal thoughts, suicidal behaviors, and likelihood for a future suicide attempt among military service members [Reference Soberay, Hanson, Dwyer, Plant and Gutierrez27].

Adults with anxiety, ADHD, depression, and cardiometabolic disease were more likely to report insomnia within our sample, which is consistent with our hypotheses as well as existent literature [Reference Javaheri and Redline29,Reference Bragantini, Sivertsen, Gehrman, Lydersen and Güzey32,Reference Wynchank, Bijlenga, Beekman, Kooij and Penninx34]. Multiple models of insomnia, including the neurocognitive model and the 3P behavioral model, illustrate how physical and psychiatric illness can be considered predisposing and precipitating events that lead to chronic insomnia [Reference Perlis, Shaw, Cano and Espie50]. It is worth noting that the direction of causality has not yet been determined. Some studies suggest that there are possible pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie associations between insomnia and other physical or mental health disorders. For example, the relationship between insomnia and cardiovascular disease may be related to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis or increased systemic inflammation [Reference Javaheri and Redline29].

It is important to consider these findings within the context of certain limitations. Our assessment of insomnia was a self-reported history and did not include current symptoms or a definition of insomnia, which may limit the precision of this measurement and result in misclassification. Previous research has demonstrated that the use of more precise definitions is related to lower prevalence rates of insomnia [Reference Ohayon26] and that reports of insomnia may depend on question wording [Reference Grandner, Ruiter Petrov, Rattanaumpawan, Jackson, Platt and Patel13]. Notably, among over 34000 adults who took part in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III, 27.3% endorsed having “problems falling or staying asleep” within the past year [Reference Olfson, Wall, Liu, Morin and Blanco37]. A positive response to that question meant the individual was classified as having insomnia. They were then asked whether a doctor or other health professional told them they had problems falling or staying asleep. If they responded affirmatively to the follow-up question, they were classified as having clinically recognized insomnia. Only 7.6% reported having clinically recognized insomnia, suggesting that a large amount of adults in the USA have unrecognized, and likely untreated, sleep difficulties [Reference Olfson, Wall, Liu, Morin and Blanco37]. Furthermore, the estimated prevalence of insomnia was 23.2% in a national sample of employed health plan subscribers [Reference Kessler, Berglund and Coulouvrat39]. This prevalence rate was based on the Brief Insomnia Questionnaire, a 32-item structured interview that was developed to determine whether an individual met criteria for insomnia as established by at least one of the following diagnostic classification systems: the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), and the Research Diagnostic Criteria/International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 (RDC/ICSD-2) [Reference Kessler, Berglund and Coulouvrat39]. In conclusion, although our measure of insomnia is imperfect, it yielded results that were generally consistent with two national studies, one of which included a structured interview based on three of the major classification systems used to diagnose insomnia [Reference Kessler, Berglund and Coulouvrat39] and another that measured sleep difficulties within a nationally representative sample of over 34000 adults [Reference Olfson, Wall, Liu, Morin and Blanco37].

Other limitations include the inability to determine causality due to the cross-sectional nature of this data. Certain subgroups had a small sample size (e.g., transgender individuals), which makes those estimates less reliable and more susceptible to change with the addition of new participants. Given that our sample was primarily recruited from one geographic location and approximately 20% of community members approached were not included in our final sample, these results may not be generalizable to broader populations. Additionally, we measured only select social determinants of health and did not directly collect data on racism or discrimination. Lastly, we did not have a measure of perceived social support for the entire sample as it was added partway through data collection. We acknowledge this data is not missing at random. Given the high percent of our sample missing these items (59.6%), we ran a separate model that restricted the perceived social support analysis to individuals with complete data (Model 2). It is important to note that the addition of perceived social support had minimal effect on the other coefficient estimates in Model 2.

We suggest that future research studies utilize a longitudinal design to better understand the development of insomnia over time or across life stages. Future projects should also use a more precise measure of insomnia, such as the Insomnia Severity Index [Reference Bastien, Vallières and Morin51]. It would also be helpful to replicate findings in larger samples of transgender individuals, given the large estimated odds ratio and unstable CI within this study. As described in a recent workshop report, using multilevel and multifactorial study designs is needed to explore causal pathways for sleep health disparities and advance the field [Reference Jackson, Walker, Brown, Das and Jones35]. Meta-analyses should continue to calculate aggregate effect sizes across multiple samples to increase generalizability. Clinically, our findings highlight the importance of screening for insomnia, particularly among patients who experience food insecurity, are military veterans, have anxiety, depression, ADHD, or cardiometabolic disease, as well as those who live alone or who have lower levels of social support.

As a modifiable determinant of health [Reference Kyle and Henry52], sleep must be optimized and has the potential to improve overall population health. We suggest clinicians and community-based providers assess for insomnia so that proper tailored treatment can be suggested. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is a first line of treatment for chronic insomnia and produces clinically meaningful improvements in sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, and sleep efficiency [Reference Trauer, Qian, Doyle, Rajaratnam and Cunnington53]. Proper insomnia treatment via CBT-i also serves to identify, treat, and support these individuals’ underlying mental health and social correlates more effectively. CBT-i has been adapted to fit the needs of many specific populations and to be more broadly disseminated. Based on a recent systematic review, most cultural adaptations of CBT-i resulted in significantly improved insomnia symptoms [Reference Alcántara, Giorgio Cosenzo, McCullough, Vogt, Falzon and Perez Ibarra54]. Adaptions included changes to the delivery modality (e.g., group-based or online setting), the use of nonclinician interventionists, shortened length of treatment, and linguistic adaptations [Reference Alcántara, Giorgio Cosenzo, McCullough, Vogt, Falzon and Perez Ibarra54]. Given the substantial public health burden of insomnia [Reference Morin and Jarrin2,Reference Hatoum, Kong, Kania, Wong and Mendelson4–Reference Ozminkowski, Wang and Walsh8], there is a crucial need to increase awareness of effective insomnia treatments and to continue advancing implementation research [Reference Koffel, Bramoweth and Ulmer55]. We recommend that future public health campaigns provide education on the symptoms and treatment of insomnia as well as promote evidence-based strategies for improving sleep.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under award number UL1TR001427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.