This is the hitherto untold history of some 100 ‘Madagascar Youths’ who, in the 1810s and 1820s, British authorities accepted for education and training in Britain, on Mauritius, and on British naval vessels. Their agreement to do so followed a diplomatic mission in 1816 to Radama I (r. 1810–28), king of the small landlocked kingdom of Imerina, in the central highlands of the large Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. This mission led first to a draft accord in 1817, which was amended and confirmed in a full Britanno-Merina treaty in 1820 through which the British aspired to suppress the slave trade from Madagascar and secure political and economic hegemony over the island. They promised the Merina king compensation for loss of slave-export earnings, notably in the form of military aid, to enable him to subject the rest of Madagascar to Merina rule, and educational and technical assistance, in the form of British missionary teachers and artisans, as well as secular craftsmen from neighbouring Mauritius. This history is well known.Footnote 1 However, there was an additional facet to the Britanno-Merina alliance that is almost completely absent from the historiography. As a result notably of the 1820 treaty, and an additional agreement in 1824, British authorities agreed to pay for ‘Madagascar Youths’, selected by Radama, to be educated and trained abroad. Accounts of two of these youths, the twin brothers Raombana and Rahaniraka, have appeared in French and Italian.Footnote 2 However, what is almost completely unknown is that the twins formed part of a group of about 100 Madagascar Youths selected for training outside Madagascar, under British supervision. The British authorities envisaged that, once they had completed their apprenticeships and returned to Madagascar, these youths would help to cement British political, economic, and religious paramountcy in the island. However, in 1826, Radama decided to break the British alliance, a decision endorsed by his successor, Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828–61). This rupture had profound implications for Britanno-Merina relations, the Mauritian and Malagasy economies, and the Madagascar Youths.

This volume comprises seven chapters. This chapter sets the context for the story of the Madagascar Youths. It outlines the history of European interest in Madagascar that led to the first Malagasy visiting Europe and to the emergence of the island as a significant supplier of provisions and slaves to European colonies in the region. It discusses the reasons for a specifically British focus on Madagascar that resulted in the 1816 mission and the Britanno-Merina accord of 1817, and the main authorities involved. It analyzes why that accord was undermined and the fallout of its failure. Finally, it examines the renewal of the alliance and its outcome in the form of the 1820 treaty that included the decision to send a select group of ‘Madagascar Youths’ abroad for training under British supervision. Chapters 2–4 investigate, in sequence, the histories of the youths sent to Britain, to Mauritius, and for training aboard British naval vessels. Chapters 5 and 6 explore the history upon their return to Madagascar of the youths sent abroad for technical training. The final chapter examines the careers of those Madagascar Youths who, upon their return, were employed for various periods as court officials and diplomats for the Merina crown. Central to this theme were the twins Raombana and Rahaniraka, who in Britain received a liberal education, rather than technical training, and who upon their return to Madagascar served the Merina court, notably as foreign secretaries.

Madagascar in the European Mind

From the time of the ‘Voyages of Discovery’, Madagascar figured large in the minds of Europeans. It did so for two very different reasons. First, it was considered to be a tropical island Eden possessing exotic animals, plants, and human inhabitants. Second, it was thought to be of significant economic and strategic importance, due to its natural resources and its strategic location on the maritime route to the East.Footnote 3

With a total land surface of 587,041 km², and a coastline of 9,935 km, Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island (after Greenland, New Guinea, and Borneo), approximately the size of Texas or 2.4 times the size of the British Isles. It is widely believed to hold the world’s greatest concentration of unique flora and fauna: 98 per cent of Madagascar’s land mammals, 92 per cent of its reptiles, 68 per cent of its plants, and 41 per cent of its indigenous bird species are found nowhere else in the world.Footnote 4 Madagascar also possesses a distinctive human population. Early European voyagers noted small communities of Swahili, who they called ‘Arab’ and the Malagasy termed Antalaotra, and Indians, called locally Karana, who probably arrived in Madagascar from, respectively, East Africa in the ninth to tenth centuries and India (notably Gujarat) in the eleventh to twelfth centuries.Footnote 5 Excluding these groups, Madagascar appeared to be inhabited by two ethnic groups: a lighter-skinned people resembling Malays who inhabited the high central plateau that runs on a north–south axis almost the entire 1,592 km length of the island and a darker-skinned African-looking people who occupied the lowlands. This was confirmed by recent DNA research revealing that, while the island’s population is of mixed ‘Bantu’ (African) and ‘Austronesian’ (Indonesian) genetic heritage, the degree of African ancestry was less (42 per cent) in the Merina of the central plateau than amongst, for example, the coastal Vezo, Mikea, and Taimoro (62–65 per cent).Footnote 6 However, all speak variants of what Europeans commonly called a ‘Malay’ or ‘Malayo-Polynesian’ (linguists now use the term ‘Austronesian’) language. This indicated that the forebears of at least some Malagasy originated from the east, from the broader Malayo-Indonesian-Polynesian region. Additionally, they possessed certain distinctly southeast Asian cultural traits, such as irrigated riziculture and rectangular huts.

The only groups in Madagascar with a clear idea of their origins were the Swahili, the Indians, and the Zafimaniry of the southeast coast who claimed that their ancestors had sailed from Mecca in the fourteenth century.Footnote 7 Other Malagasy communities had at most a vague indication that their ancestors had come from somewhere ‘overseas’. Indigenous names for Madagascar are as indeterminate. The island was traditionally termed Izao rehetra izao (‘this whole’) in accordance, claimed English LMS missionary James Sibree (1836–1929), with the Malagasy concept that their land was the centre of the universe, Nosin-dambo (‘Island of Wild Hogs’), or Ny anivon’ny riaka (‘the [land] in the midst of the flood’).Footnote 8 In many Arabic texts it was termed Kamar or Komr (‘Island of the Moon’) or ‘Bukini’.Footnote 9 The famous English explorer Richard Burton (1821–1890) considered that ‘Madagascar’ derived from ‘Mogadishu’, after the sheik of that city who had once invaded the island.Footnote 10

Merina oral traditions complicate rather than clarify the issue. They assert that the forebears of the present-day Merina were the last wave of migrants to reach Madagascar, the result of a shipwreck around the start of the sixteenth century.Footnote 11 On the coast, they suffered from disease (probably malaria) and encountered hostility from local people, so quickly made their way to the malaria-free highlands where they encountered the Vazimba, a dark-skinned Stone Age population of hunter-gatherers who spoke an unintelligible language. Many Western scholars initially assumed that the Vazimba were either a group indigenous to Madagascar or the earliest immigrants from Africa – possibly related to the Wazimba or the Khoi. The encounter between the two groups was unbalanced as the Merina, equipped with Iron Age technology, swiftly conquered the Vazimba, who they killed, assimilated, or forced to flee west.Footnote 12

Human settlers greatly impacted the environment of Madagascar. The current evidence is that people established permanent settlements in the island from the eighth to ninth centuries CE.Footnote 13 They deliberately introduced plants and animals of Southeast Asian and African origin, such as rice, bananas, dogs, and oxen, and, inadvertently, the rat and diseases – including malaria. They probably hunted to extinction the pygmy hippopotamus, a giant tortoise, and several species of giant lemur, some larger than female gorillas.Footnote 14 The island’s enormous flightless elephant birds, including the world’s largest avian species (Aepyornis maximus), probably met the same fate, as did the giant eagle, Stephanoartus mahery, which preyed on primates such as lemurs. These birds almost certainly inspired Marco Polo’s story of the elephant-carrying rukh:

it was for all the world like an eagle, but one indeed of enormous size; so big in fact that its wings covered an extent of 30 paces, and its quills were 12 paces long, and thick in proportion. And it is so strong that it will seize an elephant in its talons and carry him high into the air, and drop him so that he is smashed to pieces; having so killed him the bird gryphon swoops down on him and eats him at leisure. The people of those isles call the bird Ruc, and it has no other name.Footnote 15

Voyager accounts of Madagascar stimulated the curiosity of European savants and royalty, some of whom requested the captains of ships visiting the island to return with both natural history and human specimens. Probably the first Malagasy to reach Europe were two boys from the southeast of Madagascar. Seized by the Portuguese captain Ruy Pereira in 1506, following his nation’s ‘discovery’ of the island, they were shipped to Mozambique from where in early 1507 his superior, Tristan da Cunha (c.1460–c.1540), despatched them to Portugal aboard the Santa Maria, under the command of Antonio de Saldanha. They arrived in August 1507 and were presented to King Manuel I (1469–1521), who ordered further exploration of Madagascar.Footnote 16

In the mid-seventeenth century, several Malagasy were also taken to France as examples of exotic savages. The first to arrive, in 1655, were brothers, sons of a ruling house, again in southeastern Madagascar, where the French had founded a settlement under Étienne de Flacourt (1607–1660) which lasted from 1643 to 1674. One of the brothers was aged five years, the other was somewhat older. In France, they entered the household of Cardinal Jules Mazarin (1602–1661), chief minister to Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715), who sought to educate them as gentlemen. The eldest boy found difficulty adjusting to life in France and died of ‘grief’. However, his brother thrived in his new environment and became standard bearer in the cavalry of the cardinal, accompanying his master when he was appointed governor of Alsace, a region bordering German provinces that France had conquered in 1639. The Malagasy was described in 1675 as

a young man of about twenty-five, very well made, of average height, a perfect dancer. He had … the complexion of a negro, but it was not pure black; he was rather of an olive reddish-brown colour. What seems to me particular, is that unlike most Moors, he has straight flat hair … he had only a confused memory of his native country: did not know even two words of his mother tongue; but remembered his abduction well enough.Footnote 17

Of a third Malagasy, who was sent to Nantes, a French nobleman commented in 1658:

We came across a monster … who, however, is not so ugly or frightful that no woman in Nantes has asked M. de la Milleraye, to whom he came from Madagascar, for his hand in marriage. Avarice is at its peak, and triumphs over love and all that is invincible for those [women] who ask for him want only to run around the country displaying him for money.Footnote 18

This very much set the trend whereby, as part of a pattern of conspicuous consumption intended to reflect their wealth and status, the wealthiest members of the European elite ‘collected’ and displayed individual non-Europeans.

Madagascar was also considered to be of great strategic importance on the maritime route to the East and rich in natural resources such as tropical hardwoods. Further, contrary to conventional accounts of African gold production which largely exclude Madagascar, the island possesses significant rift and alluvial gold deposits. This was suspected by all early European voyagers and confirmed in the eighteenth century. Thus, English astronomer William Hirst (d. 1769/1770), who visited Madagascar in 1759, supported the 1729 observation by Robert Drury (1687–c.1743–50) that Madagascar produced three sorts of gold – one of which, called ‘malacassa’, was pale, as easy to cast as lead, and worth up to 20 florins an ounce.Footnote 19

As a result, Madagascar figured in a number of European schemes of colonization. From the time Vasco da Gama (c.1460s–1524) rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1497 en route to India, the Portuguese sought to supplant Muslim commercial influence in the Indian Ocean, including Madagascar. However, initial projects to colonize the island were quickly abandoned when the Portuguese encountered hostility from its inhabitants and found scant evidence of precious metals or spices. In the seventeenth century, Dutch and English attempts to establish colonies on the island also failed due to local hostility and the ravages of malaria. By the early eighteenth century, the British and the Dutch valued Madagascar only as a provisioning base for their East Indiamen– merchant ships sailing to and from the East, notably India.Footnote 20

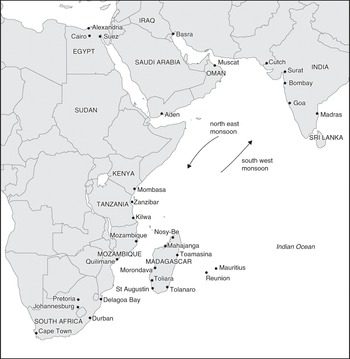

In 1642, Richelieu (1585–1642), chief minister to Louis XIII of France (r. 1610–43), granted the Compagnie française de l’Orient a charter and ten-year monopoly to colonize and exploit Madagascar. In the same year, a settlement was founded in the southeast of the island, governed (from 1648) by Étienne de Flacourt. However, in addition to malaria and the enmity of the Malagasy, it suffered a rupture in supplies from Europe during the Fronde civil wars in France (1648–53), and in 1654 the fourteen remaining colonists were removed to Réunion (called Bourbon from 1642 to 1793). In 1664, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), first minister of state (1661–83) under Louis XIV, created the Compagnie des Indes, in emulation of the Dutch and English East India companies. As the French were excluded from large parts of the East by their European rivals, the Compagnie sustained a more durable interest in less contested fields, such as Madagascar and the Mascarenes. Colbert envisaged transforming Madagascar, termed La France orientale, into a centre for French imperial and commercial activity east of the Cape (see Map 1.1). The seat of the ‘Supreme Council of Trade with India’, it would supervise imperial expansion in India and China, and cultivate cash crops for export and food crops to provision French fleets. In 1665, a colony was established in southeast Madagascar, but the last settlers abandoned it in January 1676 for Réunion. Internecine conflict, along with malaria, local hostility, and lack of metropolitan support, precipitated its collapse.Footnote 21

Map 1.1 The Western Indian Ocean

In 1649, Flacourt had asserted French sovereignty over the Mascarene Islands, east of Madagascar, claims consolidated for Réunion in 1674 and for Mauritius (called Ile de France until 1810) in 1712. The Mascarene economy flourished after Bernard-François de la Bourdonnais (1699–1753) transformed Réunion into a granary to provision both islands and passing ships and Mauritius into a major Indian Ocean entrepôt. He also encouraged the cultivation of a variety of cash crops.Footnote 22 Nevertheless, local supplies of food and labour proved insufficient, so both were increasingly sought from external sources.Footnote 23 The closest and cheapest source was Madagascar. From 1773 to 1810, 77 per cent of the 739 regional maritime expeditions from the Mascarenes charged at Madagascar, most for rice but 56 per cent also for slaves.Footnote 24 Following the decisions by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) that slavery could be maintained in the colonies (in 1802) and that the French slave trade be legalized (in 1803), it is estimated that between ten and twelve Mascarene ships, each carrying on average 100 slaves, made several return trips each year to Madagascar.Footnote 25

Following the collapse of the Flacourt settlement in 1674, French claims to Madagascar were maintained through a series of royal edicts. However, lest it come to be considered more important than the Mascarenes, the white population of Réunion and Mauritius generally opposed plans, periodically hatched in France, to colonize Madagascar. In its turn, Paris blocked Mascarene projects to colonize Madagascar on the grounds of expense and the alleged harshness of Mascarene settlers towards the Malagasy.Footnote 26

British Interest in Madagascar

In the seventeenth century, there was a brief period of English fascination with Madagascar. In 1637, Endymion Porter, a courtier, presented Charles I (r. 1625–49) with a project for the colonization of the island, the virtues of which were subsequently lauded in works published in 1640 and 1641 by passengers who had been aboard visiting English ships. The first of these volumes was written by Walter Hamond, a surgeon on the East India Company (EIC) vessel, the Jonas (or Jonah), who on one occasion spent four months in Madagascar.Footnote 27 The second book was authored by London merchant Richard Boothby. After a stopover of three months in Madagascar on a return voyage from Surat, India, Boothby enthusiastically advocated the island to rivals of the EIC as an ideal location for a European colony:

without all question, this country far transcends and exceeds all other countries in Asia, Africa, and America, planted by English, French, Dutch, Portuguese, and Spaniards: and it is likely to prove of far greater value and esteem to any Christian prince and nation, that shall plant and settle a sure habitation therein, than the West Indies is to the king and kingdom of Spain: and it may well be compared to the land of Canaan, that flows with milk and honey a little world of itself, adjoined to no other land, within the compass of many leagues or miles, or the chief paradise this day upon earth … In further commendation thereof, I will take the liberty of extolling it, I hope, without offence, as Moses did the land of Canaan: ‘It is a good land, a land in which rivers of waters and fountains spring out of the vallies and mountains; a land of wheat and barley, of vineyards, of fig-trees and pomegranates; a land wherein thou shalt eat without scarcity, neither shalt lack any thing therein; a land whose stones are iron, and out of whose mountains thou mayest dig brass.’Footnote 28

However, an attempt in 1645–6 by wealthy English merchant William Courteen (1572–1636) to found a colony of 145 men, women, and children in Saint Augustin Bay collapsed within a year, following the death of over 50 per cent of the settlers.Footnote 29 Efforts in 1649–50 to establish an English colony in northwest Madagascar also failed, due to malaria and the hostility of local Malagasy.Footnote 30

Subsequently, from 1680 to the 1720s, Madagascar commanded English attention because European pirates, chased from the Caribbean, made it their main base for raids on East Indiamen. The pirates included Scotsman William Kidd (c.1654–1701), Englishmen Henry Every (1659–c.1699–1714) and Thomas Tew (1649–1695), and Bermuda-born Creole, John Bowen (d. 1704). Piracy in the Indian Ocean inflicted such losses to European merchants that, in a rare show of solidarity, the French and British navies combined in a successful effort to drive them away by the early 1720s.Footnote 31

Of ultimately greater consequence was the threat that French possession of Mauritius posed to British East Indiamen and the maritime route to India. Ottoman control over the Red Sea meant that Europeans sailing to and from the Indian Ocean arena had to use the Cape route to India, on which Madagascar and the Mascarene islands, notably Mauritius, played increasingly significant roles. Mindful of the significance of Bombay for the British, Bourdonnais, governor of Mauritius from 1735–40, transformed Port Louis, the island’s capital, into a major port and dockyard that played a pivotal role in French imperial adventures in the region. For example, during the Wars of Austrian Succession (1740–8), the Mascarene fleet harassed British shipping, annexed the Seychelles in 1743, and in 1746 routed the British squadron under Admiral Edward Peyton (d. 1749) before relieving the siege of Pondicherry and capturing Madras – then Britain’s most important Indian possession. Again, from 1780 to 1783, over 100 French ships sailing to India called for provisions at Mauritius, which in 1781 also supplied recruits to fight the British in India. So important had Mauritius become by 1785 that Antoine Joseph de Bruni, chevalier d’Entrecasteaux (1737–1793), commander of the French navy in the Indian Ocean, and governor of Mauritius from 1787 to 1789, successfully argued for the French regional headquarters in the Indian Ocean to be transferred to Mauritius from Pondicherry.Footnote 32

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars proved decisive. In 1793, the disorganized French navy could spare no ships for the Indian Ocean and the British quickly captured French bases in India. In 1796, the British destroyed French trading posts on the northeast coast of Madagascar and occupied the Cape of Good Hope, which it then declared it a colony in 1806, in order to prevent the French from using it, as they had in 1778, to supply the Mascarenes.Footnote 33 However, Mascarene corsairs inflicted enormous damage to British East Indiamen. For instance, from 1807 to 1809 the EIC lost a minimum of forty ships to Mascarene privateers who, between 1793 and 1810 seized from EIC ships an estimated £2.5 million worth of booty. This transformed Port Louis into a major international emporium, and the Mascarenes were recognized as the maritime ‘key to the East’. Given the Russian presence on India’s northern frontier, the British considered it vital to secure mastery of the Cape route to India, and in a prolonged campaign from 1809 to 1811 they captured Mauritius, Réunion, and the French posts in Madagascar.

Under the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Réunion was returned to France, but Mauritius was retained by Britain, which subsequently attempted to extend its influence over the region. This inevitably included Madagascar, the chief supplier of provisions and cheap labour to the Mascarenes, and led to a treaty, signed in 1820, between the British and the Merina of Madagascar that laid the basis for one of the most remarkable accords of the early nineteenth century between a European power and an African sovereign, through which the British government paid for the education and training abroad of some 100 Malagasy youths.Footnote 34

The Main Authorities Involved

The main authorities involved in the Madagascar Youths project were, on the British side, Robert Farquhar, governor of Mauritius, and the London Missionary Society and, on the Malagasy side, King Radama of Imerina.

Robert Farquhar

Robert Townsend Farquhar (1776–1830; see Figure 1.1), first British governor of Mauritius, was born in 1776, the second son of Walter Farquhar (1738–1819), royal physician, and his wife Anne (née Stephenson; d. 1797). He attended Westminster School, and in 1793, aged seventeen, obtained an EIC writership in Madras. He served as British commercial resident in Amboyna (present-day Ambon, Indonesia) from 1798 to 1802, when he was appointed commissioner for adjusting the British claims to the Moluccas, with responsibility for transferring those islands to the Batavian Republic. In 1804–5, he acted as lieutenant-governor of Prince of Wales Island (Penang).Footnote 35 During these early years of service in the East, Farquhar acquired a reputation as an efficient, ambitious administrator and gained the approbation and support of Lord Wellesley (1760–1842), governor general of India from 1798 to 1805. On 10 January 1809, Farquhar married Maria Frances Geslip de Latour (1782–1875), one of the two daughters of Joseph François Louis de Latour, who had left France before the revolution and settled in Madras as a banker and merchant before retiring to Bedfordshire, England.Footnote 36 Robert Farquhar and his wife had a son, Walter Minto Townsend-Farquhar (1809–1866), and Farquhar confided to Wellesley, just before joining the Mauritius campaign, that he enjoyed a ‘very happy marriage’Footnote 37 – to which there is ample testimony during the years they subsequently spent on Mauritius. It appears that Maria fully accepted Farquhar’s strong attachment to his illegitimate son, Walter Farquhar Fullerton (1801–1830), born in Calcutta, who was at Eton in 1809, the year his father married Maria.Footnote 38

In 1810, Farquhar sailed to the Mascarenes with the British fleet under Commodore Josias Rowley (1765–1842), which captured Réunion in July that year and Mauritius the following December. Farquhar made Mauritius his base, serving as governor and commander-in-chief in 1810–17 and in 1820–23. He immediately recognized the dependence of Mauritius, as a plantation island, on slave labour imported from Madagascar and East Africa. He also realized the significance of Madagascar as a supplier of provisions. In 1746, before sailing to India to beat the English fleet and seize Madras, Bourdonnais had sought supplies for his fleet in Antongil Bay where later French Vice Admiral Pierre André de Suffren (1729–1788) also provisioned his fleet prior to fighting the English fleet off India.Footnote 39 However, while aware of the importance of Madagascar to Mauritius, and of Mauritius in guarding the route to India, Farquhar was also charged with implementing the 1807 ban on the slave trade. The issue was a major concern, as Mauritian planters were dependent on slave labour. Moreover, the prohibition of the slave trade was the prelude to abolition of slavery. It thus raised the problem not only of combatting the slave trade in the region but also how to substitute free for slave labour. In 1807, Farquhar had published ‘Suggestions for Counteracting any Injurious Effects upon the Population of the West India Colonies from the Abolition of the Slave Trade’, in which he proposed a project for the introduction into the West Indies of free Chinese labour to be paid for by planters or the government.Footnote 40 On Mauritius, Farquhar had the opportunity to implement similar migrant labour schemes. Between 1810 and 1823, he introduced over 1,500 convicts from Bengal, Bombay, and Sri Lanka, who were to be employed chiefly in road building and maintenance in Mauritius.Footnote 41 Also, between 1817 and 1840, over 100 Mauritian prisoners, slaves and free, convicted chiefly for theft, were despatched from Mauritius to Sydney, Australia, to work on penal labour projects.Footnote 42

Figure 1.1 Robert Farquhar (1776–1830).

Further, Farquhar authorized the employment of slaves, called ‘Government Blacks’, in an arrangement first established in 1786 when the French authorities purchased 286 slaves to replace a traditional system whereby slave owners were periodically obliged to supply slaves for public works. After the British seized Mauritius in 1810, they employed Government Blacks in many areas, including servicing the military, and hired them out to individuals. In 1831, the number of Government Blacks stood at about 1,300. Government Blacks were differentiated from Prize Negroes – slaves captured aboard slaving ships by the British Navy – some 3,000 of whom were landed on Mauritius between 1813 and 1827. ‘Liberated’ from slavery, Prize Negroes were immediately obliged to serve fourteen-year apprentices, most to private individuals but some in the British military and in colonial government departments.Footnote 43

Farquhar developed a strategy of incorporating Madagascar into Britain’s informal empire through seeking alliances with Malagasy chiefs and persuading them to ban slave exports, founding a British settlement in Madagascar, and encouraging British missionaries to travel to the island, under his protection, to promote Christianity, the English language, and more generally the values of European civilization (see Table 1.1). To facilitate the realization of his ambitions, Farquhar built up a formidable library of primary and secondary material relating to Madagascar.Footnote 44 From the outset, he also envisaged inviting select Malagasy youths – his predilection was for those who as adults would become chiefs – to receive an English education outside Madagascar and return to their native island imbued with civilized values and pro-British sentiments.

Table 1.1 British intervention in Madagascar, 1811–20

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1811 | Capture of French trading posts at Tamatave and Foulepointe, northeast Madagascar – abandoned due to malaria |

| 1814–15 | Attempt to establish a settlement in Antongil Bay, northeast Madagascar – settlers massacred by Malagasy |

| 1815 | Temporary British occupation of Tamatave and Foulepointe |

| 1815–16 | Mauritian settlers attempt to establish plantations near Tamatave – failure (malaria/cyclones?) |

| 1816 | Second attempt to establish a colony in Antongil Bay – abandoned due to malaria |

| 1816 | Embassy to Imerina returns with two Merina princes for education in Mauritius |

| 1816–17 | Embassies to Imerina |

| 1817 | Draft treaty with Radama, king of Imerina – General Hall, interim governor of Mauritius refuses ratification |

| 1818 | LMS mission to northeast coast fails due to malaria |

| 1820 | Britanno-Merina treaty grants right of settlement in Madagascar to British subjects and provides for training of Malagasy Youths in Mauritius and Britain |

Note: See Campbell, ‘Imperial Rivalry in the Western Indian Ocean’.

In late 1815, Farquhar attempted to found a British settlement at Port Louquez (Lokia), in northeast Madagascar, under the leadership of two army officers, Birch (or Burch) and Bleuman, who renamed the locality Port Farquhar, in the governor’s honour. However, after Birch, an inexperienced young man, struck ‘Chichipi’, a Malagasy chief who had complained about not having received the customary gift of blue cloth, Chichipi’s subjects massacred the colonists. Another attempt to settle Port Loquez in 1816 under army lieutenant [Bibye/Bybye] Le Sage (d. 1843), accompanied by British naval lieutenant Vine and a party of volunteer Mauritian Créole soldiers, was abandoned due to continued local hostility and the ravages of malaria which, endemic on the Malagasy lowlands, generally killed about 80 per cent of Europeans who attempted to settle in the island and incapacitated the rest.Footnote 45

In April 1816, acting on reports that the interior of Madagascar possessed a healthy, malaria-free climate, Farquhar sent an embassy to Radama, king of Imerina.Footnote 46 The embassy was headed by Jacques Chardenoux (or Chardenaux) (b. c.1766), a former trader to the island, who was instructed to inspect the prospects for a British settlement. Chardenoux, who was well known to Radama, opened discussions for a possible treaty with Britain that would include a ban on slave exports, and invited the king to send young members of his court to Mauritius to receive an English education. Radama appeared sympathetic to the idea of an alliance on condition that, if he prohibited slave exports, the British would provide the means to develop alternative export earnings. The two agreed in principle and engaged in a blood-brotherhood ceremony. Chardenoux returned to Mauritius in August 1816, accompanied by three Merina emissaries, Rampola, Ramanohy, and Ratsilikaina; three ministers of Jean René (c.1773–1826), ruler of the main east coast port of Tamatave; and ‘two southern chiefs, and a numerous suite’ comprising thirty people.Footnote 47

The Malagasy embassy presented Farquhar with gifts comprising mainly ‘botanical and other specimens of the products and manufactures of the island, but curiously also a female dwarf, extraordinarily diminutive, being of a race peculiar to the interior of Madagascar’.Footnote 48 This may have been in response to Farquhar’s request to confirm the reports of Flacourt and others such as Louis-Laurent de Féderbe (1728–1778), governor of Fort Dauphin from 1768 to 1770, of the existence of a pygmy race called Quimos (or Kimos), said to inhabit southern central Madagascar, at latitude 22°S, about 290 km northwest of Fort Dauphin. The Quimos were said to be itinerant, lighter coloured than most Malagasy, with woolly hair and very long arms. In addition, they were excellent craftsmen, and ferocious in defence.Footnote 49 There was also widespread belief in forest-dwelling pygmy groups, including the Kalanoro of eastern Madagascar, and the Vazimba and the Mikea in the west of the island.Footnote 50

Delighted at Radama’s positive reaction to his first embassy, Farquhar despatched another in November 1816 led by Le Sage. Amongst other things, Le Sage was instructed to discuss with Radama the possibility that ‘A boy of 9 or 10 years old … live with the King’ and that a school be founded in Imerina.Footnote 51 However, in his haste to secure an agreement with Radama, Farquhar failed to heed the prevalent advice against travelling to Madagascar during the rainy season. Of Le Sage’s thirty-two-strong party – which included about twenty artillery men, a surgeon, and two interpreters – Jolicoeur and Verkey, a slave – twenty-seven died of malaria within six months. Only one of the survivors remained healthy.Footnote 52 Le Sage introduced a number of seeds, including cotton, pepper, and coffee, but attempts to cultivate them failed due to a lack of ‘husbandry’ and appropriate soil. Suffering badly from malarial bouts, Le Sage soon returned to Mauritius.Footnote 53

Farquhar learned his lesson, and he despatched a third mission to Imerina in June 1817, during the next dry, and thus healthy, season. It was led by James Hastie (1786–1826; see Figure 1.2). Born into a Quaker family in Cork, Ireland, in 1786, Hastie had from an early age thirsted for adventure and, despite having lost his sight in one eye because of a childhood accident, enlisted in the British Army. He served in India with the 56th regiment of foot during the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–5), and in 1815, by which time he had risen to the rank of sergeant, Hastie’s regiment was posted to Port Louis, Mauritius. There, in September 1816, he distinguished himself in saving Government House in the capital from burning down:

On 25 September 1816 a fire broke out in a government warehouse in Port Louis close to a gunpowder depot. When a volunteer was called for to put out the fire, Hastie offered himself. He drenched a blanket with water and covered himself with it; then using his mouth, he carried water in a bucket, climbed onto an already burning joist, and threw the water onto the flames. After emptying the bucket, he threw it down attached to a rope so that more water could be put in it and remained there until the fire had been extinguished. By risking his life, he saved the city and many human lives.Footnote 54

This exploit led Farquhar to recommend Hastie for a commission and appoint him preceptor to the two Merina princes who Radama had sent to receive British government instruction on Mauritius (see Chapter 3).Footnote 55

Figure 1.2 James Hastie (1786–1826).

In mid-1817, the princes returned to Madagascar with Hastie. On landing at Tamatave, they were met by Radama, who, at the head of an army of 30,000 men, had just established Merina control over the major trade route linking the highland interior to the northeast coast.Footnote 56 Only the arrival of Hastie aboard a British warship deterred the king from annexing the port. On 9 July 1817, René acknowledged Radama’s suzerainty and signed a ‘Treaty of Amity and Alliance offensive and defensive between His Majesty RADAMA King of Ova [i.e. Imerina] and Dependencies on the one part and His Elder Brother JOHN RENE King of TAMATAVE and Dependencies on the other part.’Footnote 57 Radama’s boldness in marching on Tamatave so impressed Farquhar that he altered his conception of the Merina role within the envisaged British colonization of Madagascar. Thus, he announced Radama to be ‘a most powerful and intelligent, but still semi barbarous and superstitious Monarch’ who might hold ‘the destinies of the vast, populous, and fertile, but ill-treated Island of Madagascar entirely in his hands.’Footnote 58 However, he underlined to Radama his protectorate status and emphasized that ‘this happy and powerful and flourishing island of Mauritius is but as one drop of rain compared with the great ocean, when considered as a part of the wealth and power and glory of my Sovereign, whose friendship I will obtain for you.’Footnote 59

On reaching Antananarivo in August 1817, Hastie replaced Le Sage in negotiations with Radama. Farquhar instructed Hastie that he would send HMS Phaeton to Tamatave towards the end of September that year and that he anticipated that Radama would be there to sign the treaty and would appoint two Malagasy envoys to accompany the treaty to London: a Merina ambassador – Farquhar considered Rampola to be a good choice – and a scribe capable of writing Arabic.Footnote 60 In the draft treaty, duly signed in Tamatave on 23 October 1817 by Thomas Robert Pye (fl. 1808–1836), a naval lieutenant serving as chief British agent in Madagascar, Radama pledged to ban the slave export trade – much to the disgruntlement of many of the Merina elite who had become rich on the traffic in slaves. Farquhar upgraded Radama, naming him king of all Madagascar. Further, he promised Radama military aid to subjugate the other peoples of the island, technical assistance to promote the development of legitimate exports, and compensation (called the ‘Equivalent’) for the ban on slave exports. He also insisted that Radama accept a resident British agent at the Merina court.Footnote 61

The draft treaty was, on the Merina side, written in Sorabe (Malagasy written in Arabic script), probably by Andriamahazonoro (d. 1838) and Ratsilikaina, two Taimoro from the southeast of the island where scribes traditionally wrote on handmade paper and Ravinala leaves.Footnote 62 It is also worthy of note, in the context of the ban on the slave trade, that Farquhar instructed the first official expedition to Madagascar to assess the potential for the employment there of Indian convict workers, particularly in silk weaving, and dyeing,Footnote 63 and assigned convicts to accompany all subsequent missions. For example, in 1816–17, Hastie took with him to Madagascar at least eighteen such convicts, possibly as many as thirty-one. From 1815 to 1817, Farquhar granted various agents he sent on missions to Madagascar a minimum of twelve government slaves.Footnote 64

Hastie returned to Mauritius with the 1817 draft treaty, which Farquhar took to Britain for ratification, unaccompanied by any Malagasy representation. On leaving, he ordered Hastie to return to Imerina: ‘you will proceed to Madagascar with the Ministers and suite of King Radama, as soon as a passage can be procured, where you will consider yourself as the Chief Officer of His Excellency’s Government.’ He was to give Radama the ‘Equivalent’, comprising articles of ‘the first quality’. Moreover, his pay – which as second assistant to the agent for Madagascar had been $150 per month – was from 20 June 1817, the date of his appointment as chief British agent in Madagascar, to be raised to $200 per month.Footnote 65 As soon as he reached London, in early 1818, Farquhar met the London Missionary Society directors to discuss the Madagascar mission.Footnote 66 However, within a few months, all Farquhar’s aspirations had been crushed – for Gage John Hall (1775–1854), his temporary replacement, repudiated the Merina alliance and, abolishing the position of British agent in Madagascar, recalled Hastie.Footnote 67

The London Missionary Society (LMS)

The LMS was founded in 1795,Footnote 68 part of an intense upswell of British evangelical interest in converting the heathen in the British Isles and abroad that also extended to Jews and, notably from the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), to Catholics.Footnote 69

Initially, the LMS supported the view of Anglican evangelical Thomas Haweis (1734–1820) that their overseas missionary endeavour should be concentrated upon heathens ‘in an inferior state of knowledge and civilization’.Footnote 70 In this spirit, a mission was despatched in 1796 to the Pacific, a field that had caught the public eye after the three voyages of James Cook (1728–1799) between 1768 and 1779, and another mission was contemplated for Africa.Footnote 71 However, following the failure of the first South Seas mission, David Bogue (1750–1825), a Scottish evangelical and one of the society’s founders, persuaded the LMS to back his viewpoint that missionaries required special training and that the society should pay greater attention to non-Christian societies that possessed a higher civilization. As director of Gosport Academy, which gave specialist missionary training to LMS candidates, Bogue followed Enlightenment thinking in teaching that there existed a clear global hierarchy of civilization. At the top came Western European Christian societies, followed by literate monotheistic societies, namely Jews and Muslims. Next came non-monotheistic societies that had attained a high level of literary and technical achievement, such as the Chinese, the Japanese, and the Hindus. These were followed by less-civilized non-literate pagan societies, such as the indigenous ‘Indians’ of the Americas, and finally the barbaric dark-skinned pagan peoples of the South Seas, New Guinea, and sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 72 He subsumed these into two broad categories. The more civilized group were distinguished by populations that were large, spoke a common language, possessed a literature, enjoyed widespread literacy, encouraged mental ‘improvement’, and promoted significant exchange with other peoples.Footnote 73 By contrast, less civilized societies were characterized by small populations and geographical size, minority languages with restricted linguistic range, illiteracy, lack of intellectual activity, limited domestic interactions, and minimal foreign relations and influence.Footnote 74 The more civilized mission fields should be reserved for ordained men with a missionary vocation who ‘possess superior talents’ and ‘whose understandings have received considerable enlargement by a previous attention for a longer term to the sources of knowledge’ that thereby endow them with ‘a high degree of intellectual improvement.’Footnote 75 Once in the field, they might apply with advantage not only their classical training but also the ‘Useful sciences Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Geometry, Chemistry &c.’Footnote 76 Missionary candidates for more barbaric countries should comprise either industrious students of comparatively poor education, who had nevertheless graduated from the missionary seminary to become ordained, or artisans ‘unqualified for the higher branches of Missionary duty’,Footnote 77 who could instruct in agriculture and the ‘Common arts Carpenter, masons, Black-smiths, weaver &c.’Footnote 78

From the outset, Bogue enthusiastically supported the idea of a mission to Madagascar, which the LMS classified as part of Southern Africa.Footnote 79 He presented to the first and second LMS general meetings, on 25 September 1795 and on 13 May 1796, a memoir written by Andrew Burn (1742–1814), a fellow evangelical Scot and a retired soldier, advocating the establishment of a mission in Saint Augustin Bay, in southwest Madagascar.Footnote 80 In 1799, the LMS sent John Theodosius Van Der Kemp (1747–1811) to establish in South Africa a missionary endeavour that he aspired to extend to Madagascar. From 1805–6, when Van Der Kemp manumitted and married sixteen-year-old Sara van de Kaap/Sara Janse (1792–1861), the daughter of a Malagasy slave woman, this aspiration deepened.Footnote 81 In October 1811, following the British capture of the Mascarenes, Van Der Kemp heard from Mauritius that ‘the Governor (Farquhar) was very desirous that a Mission sh[oul]d be established on Madagascar that he would give a free passage to that island and also presents for the Chiefs &c.’Footnote 82 Van Der Kemp thus determined to found a mission in Madagascar.

Two months later, in December 1811, Van Der Kemp died while preparing to leave for Mauritius.Footnote 83 The LMS reacted in 1812 by sending John Campbell (1766–1840) to examine their South African enterprise and ‘to obtain information respecting the island of Madagascar, to which the Society are anxious to send a mission’.Footnote 84 Campbell received most of his information about Madagascar from William Milne (1785–1822), an LMS missionary appointed to China who sailed there via the Cape and Mauritius in 1812–13. It was a minor miracle that Milne’s account reached Campbell. Milne despatched the information in a letter, from Macao, entrusted to the William Pitt, an East Indiaman that sank some 240 km off South Africa with the loss of all lives. In his letter, one of a number wrapped in a wax cloth parcel that washed ashore in Algoa Bay and was salvaged, Milne suggested that the best locations for a European mission were in the south and southwest (Saint Augustin Bay) of Madagascar.Footnote 85

In 1814, the LMS appointed Jean Joseph Le Brun (1789–1865) missionary to Mauritius with instructions to prepare the groundwork for an LMS mission to Madagascar.Footnote 86 Farquhar asked the LMS to authorize him to send Le Brun to Madagascar, ‘promising him protection and assistance’.Footnote 87 The LMS instead considered sending to Madagascar George Thom (1789–1842), a missionary in Cape Town.Footnote 88 This plan evidently didn’t work out, probably due to Thom’s marriage in December 1814 to Christina Louisa Meyer (1785–1817).Footnote 89 This act ruled him out as a candidate for Madagascar to which, because of the notoriety of ‘Madagascar fever’ (malaria), the LMS initially determined to send only bachelor missionaries.Footnote 90 Subsequently, the LMS resolved to look for other candidates in Britain. They noted in May 1815, ‘The Governor [Farquhar] having expressed his earnest desire to promote a mission to the island of Madagascar, the Directors have resolved to commence that work as soon as proper instruments can be obtained, with which they hope soon to be furnished.’Footnote 91 This message was reiterated at the LMS general meeting in May 1816,Footnote 92 but as they delayed appointing an agent, Farquhar grew impatient and in October that year asked Le Brun directly to accompany Le Sage’s expedition to Imerina, due to leave the following month. Le Brun refused to Farquhar’s invitation – which was fortunate for him given the ravages caused by malaria to the members of the expedition.Footnote 93

However, in October 1816, the LMS finally appointed two missionaries to Madagascar.Footnote 94 In accordance with their policy of reserving the most cultivated and educated missionary candidates for the more civilized pagan realms, such as China and India, and less refined candidates for ‘barbarous’ regions of the world, the LMS selected for Madagascar, an uncivilized island, David Jones (1796–1841), a native Welsh-speaker of West Walian peasant origins, and Stephen Laidler (1789–1873), an Englishman who came from an ill-educated and impoverished background.Footnote 95 They were scheduled to leave Britain in January 1817, but their departure was delayed when Laidler requested to continue his missionary studies at Gosport. He was replaced by Thomas Bevan (1795–1819), who was of rural Welsh-speaking stock, born into a peasant family of ‘low circumstances’ in West Wales.Footnote 96

Jones and Bevan refused to accept the LMS directive that they go to Madagascar as single men. Facing potential competition from the Methodists, who were investigating the possibility of establishing a mission in Madagascar, the LMS directors relented. The Welshmen and their wives reached Mauritius in July 1818, only to discover that Farquhar, their promised benefactor, had left for London with the draft Britanno-Merina treaty. Hall, the interim governor, refused to honour the draft treaty and broke off relations with Radama. Thus deterred from their intended destination of Imerina, Jones and Bevan attempted to establish a mission under the patronage of Jean René on the northeast coast of Madagascar – with disastrous consequences.Footnote 97 In August 1818, Jones and Bevan sailed to Tamatave, leaving their pregnant wives on Mauritius.Footnote 98 Hall sent with the missionaries two government slaves as interpreters and two army medical officers ‘who understood the treatment of the Malagasy fever’ – Dr W. A. Burke (appointed chief of the medical department and physician general on Mauritius in May 1817) and Dr William Sibbald (1789–1853).Footnote 99 In Tamatave, the missionaries received an invitation from Radama to settle in Imerina ‘but on account of its distance, the badness of the roads, and the great expense which would have been incurred by the journey, they respectfully declined’.Footnote 100 Their refusal to go to Imerina was probably due to political pragmatism, for by 1818 René appeared to be the leading political authority in Madagascar. René was born in Fort Dauphin in about 1773 to an Antanosy female slave and Bouchet, a Mauritian Creole agent of the Compagnie des Indes. He was raised and educated on Réunion or Mauritius before returning to Madagascar, where a devoted guard of 100 Africans helped him seize Tamatave from its ruler, Tsiatana. René subsequently assumed the title of mpanjakamena (‘red king’ – red being the colour of royalty and mpanjaka mena meaning, symbolically in this instance, a sovereign both of whose parents were of royal line)Footnote 101 and placed Fiche (or Fisatra), his half-brother, as chief of Ivondrona, a settlement a short distance to the south of Tamatave. This enabled René to control the main east coast port and its hinterland. René, who spoke fluent Malagasy and French, sometimes ‘put on a Malagasy dress, a cashmir for a simbon [i.e. loincloth] and a kind of muslin tunic’ and at other times he ‘dressed up like an elegant creole of the period’ and ‘rode beautiful horses’.Footnote 102 André Coppalle (1797–1845), a French painter summoned to Madagascar in 1825 to execute a portrait of Radama, described René in July 1825, six months before his death, as possessing ‘a highly bizarre facial appearance; his large head, flat on the top; his patchy red colouring, hollow cheeks, sunken eyes half hidden under thick eyebrows, and moustache like a raptor give him a more savage air than any other native of Madagascar’.Footnote 103

René persuaded Bevan and Jones to start a school, on the Lancastrian plan, at Mananarezo, near Ivondrona, for ten boys, all sons of local chiefs. The pupils included Berora (c.1798–1831), son of Fiche.Footnote 104 Shortly afterwards, the missionaries returned to Mauritius for their families. Some Mauritians had warned Bevan and Jones that they were ‘going amongst a sort of stealing, poisoning, murdering and savage people who were not looked upon better than stupid wicked brutes’.Footnote 105 However, it was malaria that undermined their mission: Jones returned to Tamatave with his family on 24 November 1818 but by the end of the year his child and wife were dead, and he was desperately ill. Bevan arrived with his wife and child in Tamatave on 6 January 1819. By 3 February 1819, all had succumbed to malaria.Footnote 106

In early 1819, following the collapse of the LMS mission, René negotiated an alliance with a French agent, Sylvain Roux (1765–1823), a Mauritian Creole, later French governor of Sainte Marie (1821–3), who called at Tamatave on the French frigate Golo, under the command of Baron (Ange René Armand) Mackau (1788–1855). Roux arranged to take Berora, ‘Mandit Sara’, the child of a local chief’s daughter, and Glond, a Portuguese-Indian Creole living on Mauritius,Footnote 107 to Paris, where their education was paid for initially by the Ministry of the Marine and from 1830 by the Ministry for the Colonies. Berora went on to receive military training in France, before returning to Tamatave where he died in 1831.Footnote 108 The willingness of French authorities to pay for the education of children of Malagasy chiefs in France undoubtedly influenced future plans of Farquhar, the LMS, and Radama.

Radama

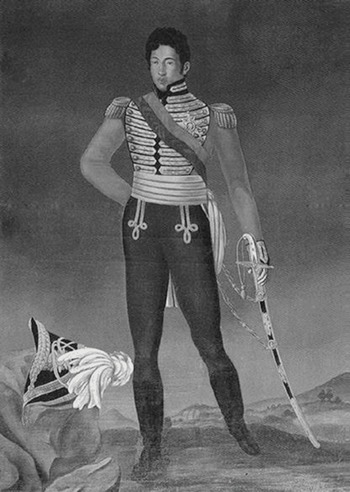

Radama I (b. c.1791–5, d. 1828; see Figure 1.3), also known as Lahidama,Footnote 109 king of Imerina, played a crucial role in the Madagascar Youths project.Footnote 110 Radama’s father, Andrianampoinimerina (c.1745–1810), described as ‘rather tall, bony and sinewy’,Footnote 111 is popularly considered to have been the founding father of the nineteenth-century Merina kingdom. One of a number of contending princes in the Merina civil wars of the late eighteenth century, he staged a coup d’état in 1787 to become king of Ambohimanga, which secured for him domination of northern Imerina, the largest market for slaves exported to the Mascarenes in exchange for gunpowder, arms, and specie. This in turn laid the basis for military success against rival princes and his domination of all Imerina by about 1794. He subsequently established his administrative capital in Antananarivo and set about raiding neighbouring highland provinces for both slaves and cattle, which were also in high demand in the Mascarenes. Under his rule, Imerina became the economic centre of Madagascar and attracted significant numbers of foreign traders, Swahili traders from the northwest coast, and European and Créole traders from the northeast coast. When Andrianampoinimerina died in 1810, he was succeeded by Radama.Footnote 112

Figure 1.3 Radama I (r. 1810–28).

There is dispute as to the year of Radama’s birth. Raombana, court secretary under Ranavalona I, who as a child had known Radama, asserted that he was born in 1782, while Europeans familiar with the king considered that he was born sometime between 1791 and 1795.Footnote 113 Radama was one of the younger children of Andrianampoinimerina, who had many wives (if not the ritual ‘twelve’ royal spouses), and numerous offspring. Rambolamasoandro (d. 1828), Radama’s mother, enjoyed sexual liberty and had several children by different men, including two half-brothers of Radama, who, when he became king, sent them to Mauritius for a year to be educated (see Chapter 3).Footnote 114 In c.1800–4, Andrianampoinimerina summoned Andriamahazonoro (d. 1838) and Ratsilikaina, two Taimoro sages from the southeast of the island, to inaugurate a palace school where, by 1817, they had taught Sorabe to five or six royal children, including Radama.Footnote 115 By 1820, according to Jones, Radama had also mastered the French language.Footnote 116 This was probably Créole French, which Radama had learned early in life from the Mascarene slave traders who visited Imerina every dry season between May and October.

Radama was the favourite son of Andrianampoinimerina, who, to ensure he inherited the throne, had his eldest son, Rabodolahy, killed, rejected the claims of his second eldest boy, Rakotovahiny, on the grounds that he had failed as a military leader, and had a third son, Ramavolahy, and many of his allies assassinated for allegedly plotting a coup.Footnote 117 While they were still children, Andrianampoinimerina arranged for Radama to be married to Rabodo/Ramavo (c.1780–1861), daughter of Andriantsalama, a close ally of Andrianampoinimerina.Footnote 118 Rabodo thus became Radama’s first and senior wife. After Radama succeeded to the throne in 1810, he followed royal tradition and, with the exception of his mother, Rambolamasoandro, married all his father’s wives.Footnote 119 He also married a further three women (see Table 1.2).Footnote 120 Radama divorced at least two of his wives,Footnote 121 two or three of his other wives lived until at least 1880.Footnote 122 Radama also maintained in Antananarivo palace a harem of select slave concubines with whom he spent considerable time.Footnote 123

Table 1.2 Radama’s wives

| Inherited from Andrianampoinimerina: | 11. Ramiangaly |

| 1. Rasendrasoazokiny | 12. Ravoandriana. |

| 2. Rasendrasoazandriny | |

| 3. Rasamana | Arranged by Andrianampoinimerina |

| 4. Ramatoaramisa | 13. Ranavalona: senior wife |

| 5. Ravolamisa | |

| 6. Razafitrimo (4–6 were sisters) | Chosen by Radama: |

| 7. Rabodomirahalahy | 14. Rasalimo (Sakalava Menabe princess) |

| 8. Rafostsirahety | 15. Ramoma |

| 9. Razafinamboa | 16. Ravo |

| 10. Rasoamananoro |

In the 1820s, Radama was described by Aristide Coroller (1799/1802–1835), a close counsellor, as about 1.6 m tall, ‘slender and small in his limbs and body, his figure in general being well-proportioned … [and somewhat contradictorily] He was broad and square across the shoulders but very small in the waist. He had a pretty hand, small feet, and fair skin.’Footnote 124 French voyager and planter, Jean-Louis Carayon (b. 1794), stated that he had an expressive face and eyes, possessed a commanding presence, and was an excellent orator.Footnote 125 Merina men traditionally wore their hair long, but in April 1822, when at his ‘country-seat’ of Mahazoarivo, Radama employed ‘an Englishman’ to cut his hair short in emulation of the British military style.Footnote 126 Naturalists Karl Hilsenberg (1802–1824), a German, and Wenceslas Bojer (1795–1856), from Bohemia, sent by Farquhar to study and collect natural history specimens in Madagascar, provided an intriguingly detailed description of the king:

He possesses considerable natural understanding and extraordinary shrewdness; he is as gay and amiable as he is hasty tempered, but susceptible of much sensibility and affection. He is very desirous of instruction, and is fond of the society and manners of Europeans, whom he does all that is possible to attract to his court, and takes pleasure in their conversation, especially on the subject of war. His chief delight is in hearing anecdotes of heroes who have distinguished themselves, and whom he neglects nothing that lies in his power to imitate. Since the period that Europeans have frequented the country, King Radama has much changed his manners, he wears their costume, adopts their manner of living, and has learned the French language, which he writes with tolerable accuracy. He is a great amateur of music, and as we can both of us play on the German flute, we often have the pleasure of his society, and of moving him and all his family, even to tears.

But all these pleasing qualities are eclipsed by his great self-love, pride, and distrust, which unfortunately have increased since the British Government has kept up an intercourse with him. He has little gratitude for friendship shown him, because he looks upon it as his rightful due; he is sometimes generous, and even capable of giving largely and granting unexpected favours, but at other times his avarice is most sordid and degrading.Footnote 127

Radama loved horse-riding, Malagasy and European music, and dancing.Footnote 128 He was also very fond of drink. Raombana asserted that intoxication with brandy influenced Radama’s decision in 1822 to execute the ringleaders of the female protest against the cutting short of his, and his officers’, hair.Footnote 129 André Coppalle, who painted a portrait of Radama, noted in 1825 that Radama preferred gin to wine, while others considered that alcohol consumption hastened Radama’s death. Thus Coroller commented that ‘Towards the latter years of his life, he was addicted to feasting and drinking to excess.’Footnote 130

Radama was a child during the last engagements of the Merina civil wars: Andrianampoinimerina captured the town of Antananarivo in 1795 or 1796, Ambohidratrimo in 1801, Anosizato in 1802, and Antsahadinta in 1803 – when he finally became ruler of what was then considered to constitute the territory of Imerina.Footnote 131 By the time of his father’s death in 1810, Radama too had become a competent military commander, leading expeditions against Ambositra in the highland province of Betsileo, to the south of Imerina, and against the Menabe Sakalava of western Madagascar. When Andrianampoinimerina died, a number of subjected towns and regions rose in rebellions that Radama ruthlessly suppressed. For example, he captured the rebel town of Ambatomanga, which commanded the eastern approach to Imerina, burnt all its dwellings, and deported its surviving inhabitants.Footnote 132

To consolidate his economic position, Radama expanded the western frontiers of Imerina through obtaining the peaceful submission of the large neighbouring provinces of Imamo and Vonizongo, rich in silk and in cattle respectively.Footnote 133 His armies overran Vakinankaratra, a significant slave supply centre to the immediate south of Imerina, and rival trade routes, such as the one in Antsihanaka, the highland province to the north, forged by the Swahili to link the west and the northeast coasts.Footnote 134 He also ordered devastating attacks upon the Bezanozano of the Ankay, to the east of Ambatomanga, to eliminate them as intermediaries in the trade with Europeans on the northeast coast. Further, he established Merina military colonies (voanjo) on the rich agricultural lands of north Betsileo and the Lake Alaotra region of Antsihanaka. By 1814, Merina-ruled territory had quadrupled in area to about 18,000 km2, creating the core of the future Merina empire. From it, a series of cattle and slave raids were launched on other peoples. In 1816, one such expedition returned from southwest Madagascar with a booty of 2,000 slaves and 4,000 cattle.Footnote 135 A few years later, Radama likened himself to Napoleon, who he considered ‘my model … the example that I want to follow’.Footnote 136 However, the destruction wrought by his military campaigns often created famine conditions and resulted in rampant insecurity along the main trade arteries, including that to Tamatave, Imerina’s most important foreign trade outlet.Footnote 137

The opportunity of an alliance with the British thus came at an opportune moment. At first, Radama resisted British pressure to ban slave exports. The slave trade financed the court and its expansionist policies and was the chief source of revenue for the Merina elite, whose support had been critical to Andrianampoinimerina’s success in the civil wars and who, from 1810, comprised the most important segment of Radama’s council.Footnote 138 Nevertheless, Radama felt that members of his royal council were too powerful and wished to increase the crown’s authority at their expense. A ban on slave exports would certainly diminish the wealth of his councillors. In order to avoid it similarly undermining royal revenues, it was imperative that Imerina develop alternative export staples and secure an immediate outlet to the coast. In June 1817, a 30,000-strong Merina force marched on Tamatave, where Radama accepted the submission of René.Footnote 139 Subsequently, the British negotiated a draft treaty in which Radama agreed to ban the slave export trade in return for annual compensation from the British, who also promised him military aid to conquer the entire island, over which, for the first time, they declared him sovereign.Footnote 140

Hall’s decision to cancel the alliance with Imerina completely undermined Radama’s new policy. It obliged him to renew the slave traffic to the Mascarenes that amounted, according to Hastie, to ‘between three and four thousand souls, at the lowest computation every year’.Footnote 141 Consequently, Tamatave quadrupled in size from 1818 to 1820, at which time it housed sixty European slave traders.Footnote 142 In 1819, in order to ensure his control over the trade, Radama despatched a Merina army to the northeast coast that killed Fiche and massacred his men at Ivondrona.Footnote 143 The Merina force was commanded by John Brady (c.1795–1835), a Jamaican Creole of Irish extraction who, as a British corporal, had accompanied the 1816 Mauritian expedition to Imerina and remained behind in Radama’s service.Footnote 144 In 1819, Brady also obliged René to again swear allegiance to Radama, although Coppalle later commented that René was ‘polite with the French whose company he enjoys, flattering to the English whom he needs, fearful of and submissive to Radama whom he dreads and hates’.Footnote 145

Further, Radama engaged Robin (fl. 1812–1830), a Frenchman, to establish a school at court instead of the one Farquhar had envisaged supervised by British missionaries. Robin was born in France where he studied medicine before, in 1812, enlisting in Napoleon’s army. Following peace in 1815, Robin travelled to Réunion. There, in 1817, he was jailed for theft, but he escaped and fled to Tamatave where Lagadière, a French trader, and René, hired him to visit Imerina – presumably to purchase slaves. In Antananarivo, Robin was engaged by a wealthy Merina cattle merchant to teach his children French. He learned Malagasy and, in 1819, married one of his Merina pupils – a fifteen-year-old called Augustine. Impressed with his teaching abilities and his military service under Napoleon, Radama hired Robin to teach him arithmetic and metropolitan French – Robin used the French versions of the Life of Napoleon and History of Tippo Saib to teach the king.Footnote 146 Robin also formed a school in Masoandro (a house in the royal compound in Antananarivo) comprising three classes, two for academic and one for military instruction.Footnote 147

In sum, it appeared that Farquhar’s long campaign to establish an alliance with the Merina crown of central Madagascar that would result in a ban on slave exports and secure durable British hegemony in the island, had failed. Hall, interim governor of Mauritius during Farquhar’s visit to Britain, annulled the draft treaty, and despatched the newly arrived LMS agents to the east coast where all bar one succumbed to malaria. Radama immediately renewed the slave trade and swung the Merina realm, incorporating the central highlands and eastern seaboard around Tamatave, the single most important port in the island, into French not British imperial sway.

Renewal of the Britanno-Merina Alliance and the Madagascar Youths Project

In mid-1820, Farquhar returned to Mauritius. He immediately ordered Hastie, who Hall had demoted, to return to Antananarivo, in the company of the LMS missionary David Jones to attempt to renew the Merina alliance. Farquhar instructed Hastie,

You will inform Radama that it is the intention of the Government to send him some good Artificers with their Tools, and that if he wishes it, we shall receive several of his free Subjects here, for the purpose of instructing them in the most useful handicraft trades. But you will by no means encourage any idea of an enlistment of Apprentices by Individuals, as People here and at Bourbon [Réunion] have spoken of, which appears rather to lead to a concealed Slave traffic, however pure the intentions of those who propose it may be supposed.

The Persons whom Radama may choose to send should be placed under the care of Mr. Jones, the Madagascar Missionary, for their instruction, and not be considered as bound to any individual, but under the special care of the Government, on the same footing exactly as those sent up by you before, on the execution of the Treaty, and who were returned to Madagascar by the Person then holding the Administration [Hall].Footnote 148

Jones informed the LMS that Farquhar had instructed him, upon reaching Antananarivo, ‘to request Radama to allow Missionaries to settle within his dominions, and, in case of his consent being obtained, to determine upon the most eligible places for Missionary Stations; to open a regular communication between Ova, Radama’s capital, and Tamatave, and to obtain his permission for some Malegache boys to return with the Deputation to the Mauritius, in order to be there instructed, under the patronage of the Governor’.Footnote 149

On 9 September, Hastie and Jones reached Tamatave. There they were well received by René, who informed Hastie that he wished Farquhar to send him ‘Indians, Chinese and, in fact, sons of every nation, and giving these people permission (subject to his approval) to obtain concession of ground here’. Influenced by his recent instructions from Farquhar, Hastie responded by ridiculing such ‘wild schemes’ and informing René that each family resident in Tamatave should place one to two boys as apprentices to mechanics in Mauritius, who, upon completion of their training, would return to Tamatave.Footnote 150

On 16 September, Hastie and Jones left Tamatave and, en route to the high plateau, passed a convoy of about 1,000 slaves, including many children, being marched to the coast for export.Footnote 151 On 3 October, they reached Antananarivo, and on 7 October entered into negotiations with Radama and his counsellors, in which Robin, who had also been appointed royal secretary, assisted. The negotiations were conducted in French,Footnote 152 a testament to Robin’s teaching ability and to Radama’s knowledge of the language.Footnote 153 On 8 October, Hastie, known locally as ‘Andrianasy’ (from Andrian – ‘Andriana’ and asy – ‘Hastie’),Footnote 154 informed the king that ‘Farquhar would receive Radama’s free subjects for instruction’ in response to which, on the following day, Radama ‘requested permission to send some of them to England, for that purpose’.Footnote 155 Overnight the king’s resolve cemented. David Jones recorded that, on 10 October, Radama informed Hastie that he would agree to a treaty on the condition

that he should be allowed to send some of his people to the Mauritius and England for instruction, and that artificers should be sent to him. Mr. Hastie said, that he was authorised by his excellency to promise artificers, and to take back some of his people for instruction, but beyond this he had no authority. The king sent again, requiring that twenty persons should be sent to England for instruction, as he was persuaded nothing but instruction could reconcile his people to the abandonment of the slave traffic. In this dilemma, Mr. Hastie consulted with me. I observed, that as the treaty would tend to open a door for the secure residence of missionaries in Madagascar, I thought it probable the Missionary Society itself would not object to take some of the proposed Malegaches under its care, for education. It was now agreed by Mr. Hastie, that six of the free subjects of Radama should be sent to England for education. This proposal was sent to the king, and his reply was, that he would again see Mr. Hastie in the evening. In the interval, we prepared a paper, containing translations into French of what the society has published relative to Madagascar in its Annual Reports, and stating, that I was sent by the Missionary Society, to ask Radama’s permission and protection for missionaries to settle in his country, and that, if he consented to grant these, I was authorised to promise, that the society would send out more missionaries to civilize, as well as to Christianize his people. I sent also, with this document, a copy of the Society’s Report for 1819, and the Missionary Sketch, which represents the people of Otaheite destroying their idols, and building a chapel. I requested the king’s secretary to explain these to his majesty, in like manner as I had explained them to him …

The next morning [11 October 1820], at eleven o’clock, his majesty sent to communicate his final determination, which was, that the treaty should be signed this day, and that he would republish his former proclamation, requiring the immediate cessation of the slave traffic, provided Mr. Hastie would agree to take twenty of his subjects for instruction, ten to proceed to the Mauritius, and the other ten to England. The moment was now arrived when the welfare of millions was to be decided. Mr. Hastie came to me and asked what was to be done, and whether the Missionary Society would take some of them under their charge. Having no authority, I could not go beyond what I had said yesterday; on which Mr. Hastie said, that he would agree to the king’s proposal, even if he himself should bear the expenses of the ten Malegache youths who were to be sent to England. The agreement was accordingly made, a kabar held, and a proclamation published.Footnote 156

The agreement formed the substance of a supplementary clause to the 1820 treaty, which Robin helped draft, in which it was agreed that ‘Mr. Hastie engages on the part of his government, to take with him, twenty free subjects of his Majesty King Radama, to be instructed in, and brought up to different trades, such as mechanicians, gold and silversmiths, weavers, carpenters, blacksmiths; or placed in the arsenals, dock yards, &c. &c. &c. whereof ten shall be sent to England, and ten to the Island of Mauritius, at the expense of the British Government’.Footnote 157 This accord formed the foundation of the Madagascar Youths project whereby, in the 1820s, the British authorities paid for the training abroad, in Britain, in Mauritius and on British naval vessels, of some 100 Malagasy youths. The next chapter explores the history of those selected to go to Britain for education and training.