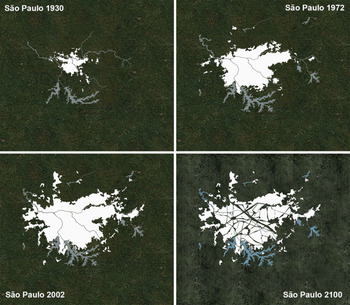

For 500 years, the urban mass of São Paulo has voided out nature, spreading itself with speed and efficiency. Fragile institutions have given way to a private logic that disregards what is public. Cars have taken up the valleys and the river, while the land has been divided, and a fragmented territory exposed its culture. In the logic of the ruling state/city, there is no space for play or for meandering. There is no space for the collective good or collective memory.

The metropolitan area of São Paulo spreads over 8,000 square kilometers with a population of 20 million people, or 10 percent of Brazil’s entire population. In the 1930s the city was remodeled to better accommodate cars and, since then, the urban logic of growth and development has followed that path.

Several consequences derived from that decision, including the disappearance of our rivers, which were buried and canalized, as our valleys became avenues. It also led to the decrease in use and importance of our public spaces, as our social lives migrated to the private realm, within walls and buildings. Today the best and the safest options for urban leisure happen in shopping malls, private condominiums, and private clubs. São Paulo became the anti-Jane Jacobs city, prisoner of a vicious cycle that walls up its buildings, abandons its streets and plazas, which then become even more dangerous and drive the walls to rise higher (Figure 26.1).

Figure 26.1 Downtown Sao Paulo in 2002.

So when in 2002 the zoning rules changed to accommodate the real estate industry’s need to sell more parking spaces and the public sector’s need to deal with the ever growing car numbers, no one seemed to mind. The new ordinance stated that one could build aboveground garages without losing any of the allowed floor area ratio, giving developers “free” building area to accommodate cars. The results were disastrous (Figure 26.2).

Figure 26.2 Walls isolate the street.

New buildings were planned to have three to five garage stories above street level, resulting in walled-up fortresses and desolated streets. In some neighborhoods one can walk for up to three blocks without encountering a single opening, a single storefront, or any sign of street life. This new architectural element, along with a zoning ordinance that rules the city’s development as an agglomeration of individual lots, created a city of walls.

Fortunately, the mindset has been changing in recent years, with citizens demanding better urban life, as several community groups and not-for-profit organizations have come together to occupy and care for public spaces. The best recognition of this change came with the city’s new master plan in 2014, which tried to promote mixed uses, street life, and use of public transportation.

It is within this new understanding that we propose to act, liberating ourselves (and the city) from the pervasive and inefficient parceling of lots defined by walls. We are not against private property. We are not against anyone’s right to own real estate. But we are against the fragmented vision of a city that imposes redundancy, isolation, and fear. We are against a city that prioritizes the car and becomes hostage within its own walls.

26.1 A Proposal

The experience of São Paulo exposes the weakness of the idea that a city should be the collection of individual lots in an ever-growing pattern of repetition and sprawl – each lot with its own garden, its own tree, its own swimming pool, its own playground, and its own walls, a fortified castle within many other castles.

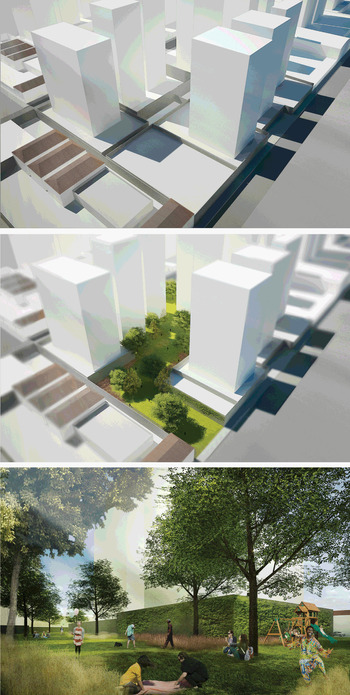

To subvert this idea, Mind the Gap proposes to reclaim the common ground by acting in the microscale of the lot, unifying urban blocks through the collective management of interstitial spaces. In a city where public spaces are regarded as no one’s land, our action provides private-owned spaces for public use (Figure 26.3).

Figure 26.3 When walls come down, space can flow.

We start by tearing down walls and other physical barriers within the block. Then we open up some of these spaces to the city and start connecting blocks, parks, plazas, and squares. We redirect the logic of flows and invite nature in. We call neighbors to cohabitate in common spaces and revert the isolation of anonymity, bringing back the basic virtues of common ground: spontaneous encounters, sedimentation of bonds, and recognition of the other (Figure 26.4).

Figure 26.4 Open private spaces are joined and opened up for common use.

The consumption rhythm of nature is reversed, as a new city structure is defined. One where the void is constant and the city develops and densifies around it, permeated by it. We advocate for the comeback of communal knowledge and the radical and simple idea of being able to practice that basic element of democracy’s foundation: conviviality (Figure 26.5).

Figure 26.5 A timeline of expanding São Paulo, but in 2100 nature starts to come back in through green corridors and open spaces.