Introduction

Research suggests that community-engaged research (CEnR) and community-based participatory research (CBPR) frameworks have the potential to build equitable partnerships, promote translational science, and improve individual and community health [Reference Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel and Minkler1]. CEnR is an umbrella term used to describe a wide range of participatory activities and approaches to promote positive health outcomes through academic-community collaborations, resource mobilization, and institutional change [Reference Eder, Evans and Funes2]. Over the past two decades, participatory approaches to science have increased exponentially to challenge traditional deficit-based scientific frameworks and build meaningful strength-based partnerships between universities and community stakeholders [Reference Barkin, Schlundt and Smith3]. This is reflected in key federal initiatives such as Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) [Reference Fleurence, Selby and Odom-Walker4,Reference Forsythe, Carman and Szydlowski5], Clinical Translational Science Awards (CTSA) [Reference Rubin, Martinez and Chu6,Reference Llewellyn, Carter, Rollins and Nehl7], and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Participatory Research Programs [Reference Minkler and Wallerstein8].

In 2006, the NIH launched their CTSA initiative to foster collaboration and support academic institution’s efforts to design and translate research to real-world settings and inform public health practice and policy [Reference Heller and de Melo-Martín9]. Engaging communities in research is one of the primary goals of CTSAs. Thus, universities have established Community Engagement (CE) programs within Clinical Translational Science Institutes (CTSI) to strengthen the knowledge and skills of community stakeholders and researchers in CEnR by developing and disseminating CEnR trainings and resources [Reference Holzer and Kass10–Reference Zerhouni12]. Given that training offerings in CEnR across institutions differ, research has introduced a community-engaged dissemination and implementation (CEDI) competency framework to develop effective CEnR partnerships by assessing the level of readiness reflected in researcher’s attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors in nine major domains: (1) perceived value of CEDI research, (2) introspection and openness, (3) knowledge of community characteristics, (4) appreciation for stakeholder’s experiences, (5) preparing partnership for collaborative decision-making, (6) collaborative planning, (7) communication effectiveness, 8) equitable distribution of resources and credit, and (9) sustaining the partnership [Reference Shea, Young and Powell13]. While research has documented the impacts of CTSA initiatives in training community stakeholders [Reference Balls-Berry, Billings and Ernste14–Reference Stallings, Boyer and Joosten18], limited research has explored key processes implemented in partnership with community stakeholders to codevelop relevant CEnR curriculum to train health researchers and doctoral students in CEnR.

For example, University of Texas Health Science Center coordinates project St. Mary’s Academic Research Team (SMART), a service-learning course that provides students with opportunities for practical experiences while partnering with a local elementary school system [Reference Marcus, Taylor, Hormann, Walker and Carroll19]. Students in these programs report creating defined outcomes with their community partners, learning new practical skills, and improving their understanding of theoretical knowledge [Reference Hynie, Jensen, Johnny, Wedlock and Phipps20]. Additionally, some schools offer non-course student research assistantships with community agencies [Reference Savan21].

CEnR approaches, such as CBPR, have also been added to medical school curricula, particularly for Family Medicine residents, partially due to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s requirement that all Family Medicine residents study community medicine [Reference Gimpel22]. At UCLA, the Family Medicine program requires residents to engage with local partners and build upon existing projects, such as a school asthma program and walking groups. Organizers note these opportunities strengthen community ties and existing partnerships, while increasing academic capacity [Reference Moreno, Rodríguez, Lopez, Bholat and Dowling23]. In Dallas, faculty from the Department of Family Medicine at University of Texas, developed a 9-week Community Health Fellowship Program (CHFP) where medical students participate in a similar CBPR training program and conduct research in the community [Reference DeHaven, Gimpel, Dallo and Billmeier24]. Many other medical and nursing programs include CE and partnership, often with an emphasis on health disparities [Reference Brosnan, Upchurch, Meininger, Hester, Johnson and Eissa25–Reference Zandee, Bossenbroek, Slager and Gordon27].

Despite increasing interest in adopting CEnR approaches and training, research suggests practical, ethical, and political challenges persist, particularly in the ways power is established, shared, and controlled across relationships, funding structures, and roles [Reference Wilson, Kenny and Dickson-Swift28]. This is particularly salient within the domain of partnership processes that take place in hierarchical research structures where researchers and community partners experience internal and external challenges in relationship building, group dynamics, conflict resolution, and decision-making [Reference Ortiz, Nash and Shea29]. Findings of NIH-funded research that surveyed 200 CEnR partnerships and conducted a series of case studies suggest key strategies to shift and redress power imbalances including the integration of bidirectional communication, critical reflection, accountability, and community culturally competent perspectives [Reference Wallerstein, Muhammad and Sanchez-Youngman30]. In order to create the conditions for social transformation in CEnR collaborations, it is important to develop and implement relevant training and resources that engages both, researchers and community stakeholders, to identify and apply ethical principles grounded in trust and accountability to honor reciprocity and address power dynamics, including racism and discrimination in the partnership [Reference Andress, Hall, Davis, Levine, Cripps and Guinn31–Reference Khodyakov, Mikesell, Schraiber, Booth and Bromley33].

In an effort to build a relevant CEnR course for graduate students and trainees across Boston University, we engaged community stakeholders, namely non-university affiliated community leaders and staff from distinctive organizations across multiple fields, in identifying priority content areas for interdisciplinary graduate CEnR education. Specifically, we examined community stakeholders’ perceptions of (1) CEnR, (2) promoting and hindering factors associated with CEnR collaborations, and (3) recommendations for the training of prospective CEnR scholars through individual semi-structured in-depth interviews. Community stakeholders are essentially the “end users” when it comes to CEnR coursework. As such their expertise and priorities are critical to informing graduate student and emerging scholar training. So sustaining meaningful university–community partnerships requires creating opportunities not only for prospective scholars to develop relevant skills, but also to gain critical knowledge and experiences from community stakeholders that challenge graduate training that privileges traditional methods to research. In addition, by developing training based on community partner priorities and expertise, we are modeling for the important CBPR principles related to recognizing the community as a unit of identity [Reference Braun, Nguyen and Tanjasiri34].

Methods

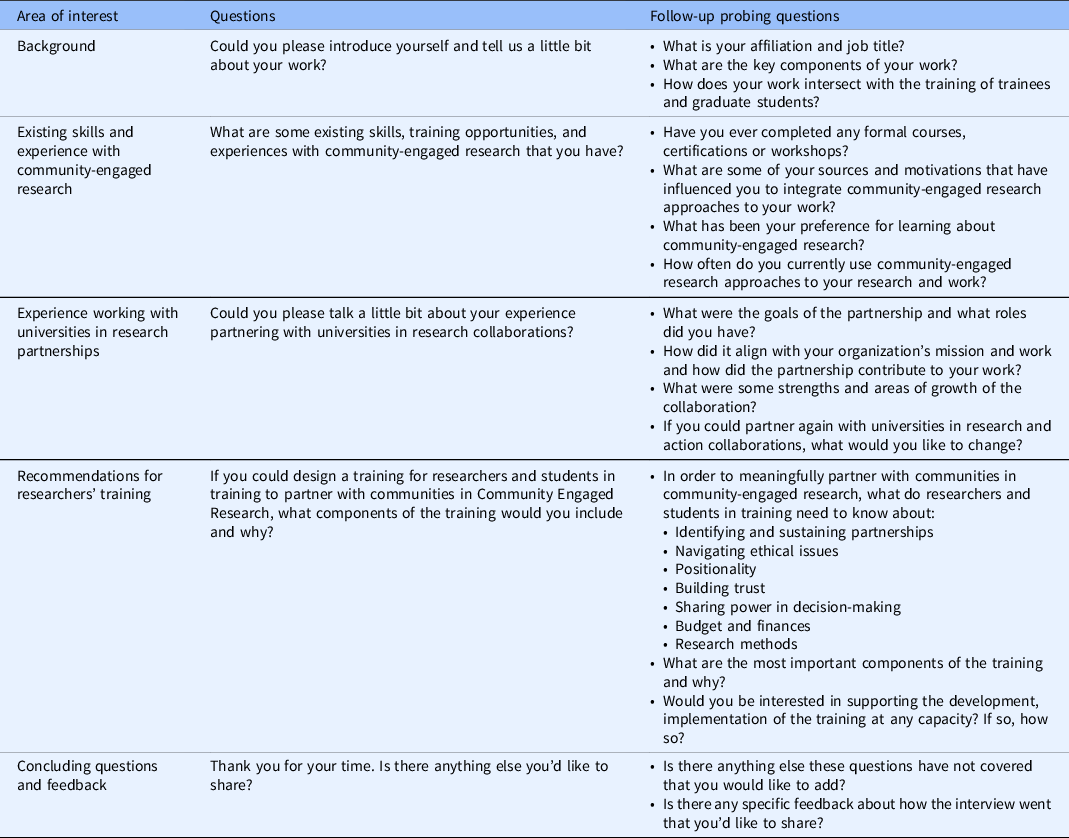

This study was approved by the Boston University Charles River Campus Institutional Review Board Protocol Number 5635X. Qualitative interviews were used to explore community stakeholder perceptions of CEnR and their recommendations for the training of prospective researchers. Community stakeholder was defined as community residents, individuals, or staff whose primary employment was not focused on research at a university and who had distinctive affiliation with social institutions from multiple fields such as educational and political grassroots community-based organizations, health centers, and municipal institutions. Additionally, community stakeholders had prior or existing experienced partnering with university faculty in conducting community engaged research. Given the exploratory nature of the research questions, qualitative methods were identified as appropriate to explore community stakeholders’ perceptions and meaning making in relation to CEnR collaborations, facilitating factors, barriers, and recommendations for the graduate doctoral level CEnR course (See Table 1). Interview protocol questions were vetted with members of the CTSI CE core and collaborators. Moreover, the interview protocol included open-ended questions to allow interviewees highlight priority areas inductively which were facilitated by one doctoral researcher with no prior experience working with the community partners identified. In-depth semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with community stakeholders (n = 13) with prior experience in CEnR in the greater Boston area. This qualitative methodology took an inductive and deductive approach to data collection and analysis where both emerging themes from the data and areas of interest identified in prior research were considered [Reference Azungah35]. Thus, in addition to including open-ended questions to explore emerging priority areas based on interviewee’s situated experiences, the interview protocol also consisted of open-ended questions that examined CEnR ethical challenges identified in previous scholarly literature such as community ownership, sustainability, and orientation to action [Reference Mikesell, Bromley and Khodyakov36]. In general, the study’s primary research inquiry as well as inductive and deductive qualitative approaches guided and determined priorities explored in the interview protocol.

Table 1. Community stakeholder interview protocol

Members of the CTSI CE Core used purposive sampling strategies [Reference Campbell, Greenwood and Prior37] to recruit interview participants through the development of a contact list of community stakeholders and collaborators. This sampling strategy was appropriate given that it allowed CTSI CE Core members to explore training priorities within a geographic catchment area relevant to the intended audience of the CEnR course at the university. One doctoral researcher from the team led the data collection phase and actively engaged in writing analytic memos and having debriefing sessions with interviewees and CTSI CE Core team members as strategies to reduce researcher bias [Reference FitzPatrick38]. The doctoral researcher from the team invited each community collaborator via email to participate in one 60-minute interview via zoom. Verbal consent was obtained from interested participants at the time of the interview. Interviewer explained interview procedures following ethical standards and reminding interviewee that their participation is voluntary and that responses will be deidentified. Interviewer provided opportunity for the interviewee to ask any clarifying questions before obtaining verbal consent to participate and have the interview video recorded. Interviews were video recorded using Zoom which generates a transcript. Zoom transcripts were cleaned by the researcher and a research assistant by proofreading transcripts and then listening to the interview and editing the transcript to match the spoken word in the text.

Interview transcripts were proofread and analyzed in NVivo software using thematic analysis. Research suggests thematic analysis is appropriate to understand experiences, thoughts, or behaviors that answer research questions, as opposed to developing mere summaries or categorizations of codes [Reference Kiger and Varpio39]. Thematic analysis consists of six key phases: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generation of codes, (3) construction of themes, (4) review of potential themes, (5) definition of themes, and (6) production of written manuscript or report [Reference Clarke, Braun and Teo40]. Multiple readings of the transcripts and annotations were conducted by two researchers. The researchers discussed the initial analysis to ensure consistency in their analytic approach [Reference Boyatzis41]. Drawing from the initial notes, a codebook was developed and entered in NVivo. All transcripts were coded separately by two researchers who assigned coding labels to text segments throughout the transcripts. Researchers met to reconcile codes and clarify any discrepancies until reaching full consensus. Once consensus was achieved, a coding report was generated, and summary reports were prepared for each code. The researchers then sorted codes into possible themes and explored relationships between themes, and codes across levels, ensuring data within each theme was both cohesive and distinct [Reference Clarke, Braun and Teo40,Reference Patton42]. The larger story within the data was then identified, and illustrative quotes were selected to develop a clear and concise story within and across the identified themes [Reference Clarke, Braun and Teo40].

Findings

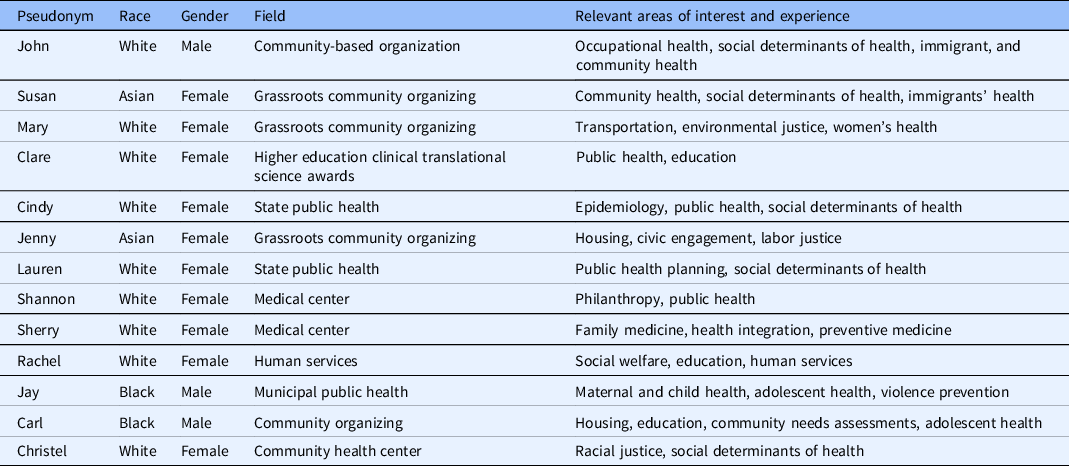

Interviewees had relevant interests and experiences (See Table 2). Community stakeholders interviewed (n = 13) represented a wide range of fields and including nonprofit community-based work (n = 3), government (n = 2), higher education (n = 1), medical science (n = 2), human services (n = 1), public health (n = 1), community health (n = 1), and community organizing (n = 2). Racial identities most represented included White (n = 9) followed by Asian (n = 2) and Black (n = 2). All individuals interviewed were affiliated with a distinctive institution that had prior or current experience partnering with university faculty in CEnR. There were no individual participants representing multiple organizations or institutions. Most of the interviewees identified as female (n = 13) and CBPR collaborations were concerned primarily with community health and public health. Interviewees shared a wide range of experiences, perceptions, and recommendations to inform CEnR training. Recommendations ranged across multiple domains including CEnR partnership development, research methods, and course format. This article focuses primarily on researcher training and skill development, specifically on building meaningful and equitable partnership development processes, which was the most referenced code across all interviews. Within this domain, there were four major priorities that emerged: (1) researcher’s positionality, (2) power-sharing, (3) funding, and (4) ethics. Each of these themes are described and illustrated through participant quotes.

Table 2. Community stakeholders demographics

Note: Relevant areas of interest and expertise are not exhaustive. Each community stakeholder represents a distinctive institutional affiliation.

“People have to kind of challenge themselves to really understand what is your motivation for doing this research”: Training for Researchers About Positionality

Positionality refers to researchers’ seen, unseen, and unforeseen racialized and cultural subjectivities that shape researchers’ views, perspectives, and biases [Reference Milner43]. Throughout the interviews, community stakeholders emphasized the importance of prioritizing researchers’ critical awareness of their personal motivations, biases, and community’s history in CEnR training programs.

I think people really need to be cognizant of how their own worldview, biases, and presumptions can negatively impact… people have to kind of challenge themselves to really understand what is your real motivation for doing this research… and I think a community engagement curriculum has to push that really hard question at the front end, not in the middle of the process, or in the back end, but from the very first day. It has to be designed in a way that really challenges people’s assumptions, challenge what they’re comfortable with… you have to acknowledge certain realities and if you don't acknowledge those realities, then you kind of operate in a world that’s not real… you miss an opportunity to really address some core issues.

In addition to ensuring a critical examination of individual motivations and biases is integrated in the training of CEnR scholars, community stakeholders described the importance of investing efforts to learn further about community’s expertise and stepping out of academic settings that were removed and disconnected from community stakeholders’ worlds.

The more you sit in the chair of academic, the more you start valuing academia, the research. On the idea of like getting out of that chair and sitting with community, learning about expertise, learning about historical efforts like that’s critical, for I think some type of training.

Moreover, community stakeholders recommended researchers to integrate a critical lens to their role in research by interrogating the implications of traditional scientific neutral and objective stance and linking the production of knowledge to critical theory to advance community-driven priorities. Among the frameworks discussed, Critical Race Theory (CRT) – a framework developed by legal scholars of color that defines a set of antiracist tenets to eradicate systemic racism in the social fabric of society, including the ways it is embedded in biomedical institutions and research [Reference Ford and Airhihenbuwa44–Reference Delgado and Stefancic46] – was suggested as an essential approach to challenge individual assumptions of research in the context of health promotion.

…all researchers need to be critical race theorists…it’s impossible to be objective… we have to unlearn that assumption that we could be objective… there is a role for research. I think it should be called something different. It’s going to look totally different. But we do need people who help us codify and measure for justice, healing, and community stabilization… a practice that researchers really need to understand is like pop ed [popular education]. … As we decide what we want to start measuring and looking at, there has to be a way that we democratize the learning.

Overall, community stakeholders highlighted the importance of CEnR scholars to develop relevant knowledge and skills that can increase researchers’ critical awareness of their positionality, biases, and assumptions.

“We’re not going to have a problem with your deliverables, just get off my back”: Sharing Power Equitably in Partnerships

In addition to being able to critically examine individual biases and motivations, community stakeholders underscored the importance of recognizing and shifting power imbalances by listening, fostering community ownership, and recognizing the limitations of hierarchical structures. “Building trust” and “listening” to community stakeholders’ experiences and perspectives “before you can jump in and just take action” were described unanimously as essential skills in equitable CEnR partnerships. One community stakeholder added: “I think building trust is critical, learning how to listen, learning how to ask open-ended questions, learning how to get out of your own way and in terms of what the agenda is of the community and meet community members where they are.” Community stakeholders recognized the presence of power imbalances in their partnerships and the importance of integrating key strategies in the CEnR course to promote shared leadership and ownership in “open, transparent, and respectful” collaborations.

Despite the importance and benefits of building trust and listening, community stakeholders also discussed experiencing major tensions and power dynamics associated with hierarchical research and funding structures. For example, a longtime community organizer working over 5 years in partnership with faculty in environmental health research highlights tensions experienced when faculty questioned her role, participation, and ownership in the project:

[Name of PI} would question like, you know, we're paying this much, you know, for this much of your time and I don't see you… if I would miss some meetings he would start getting irritable and saying, you know, You can't, you know, we're paying you this for this much and your time and you know you're not even like showing up at meetings and I would just get like I would get pissed off at him, I'd be like, you know, I just missed these different meetings for a good reason. You know, don't worry. And he would start like saying, you know, it’s not that you have to be at every meeting, but you know we have to make sure that you're going to do these deliverables. And I'm like, we're not going to have a problem with your deliverables, just get off my back.

As illustrated in the quote, the community organizer describes the frustration and tension experienced because of the researchers’ efforts to reinforce institutional norms and practices that are static and rigid. Moreover, limited communication regarding organizational norms as well as limited capacity were associated with hierarchical power structures of funding. One community stakeholder stated:

I think our funding structures don't really allow us to do that… It’s very rare that there’s a grant opportunity where you can actually give half your budget to community residents, stakeholders. Money is power. If the grant institution is saying it has to be one way, how do you share power when you can't cover the time and effort of folks that are community stakeholders? I think we see ourselves as collaborate, collaborate, collaborate, but probably don't get to the power sharing side of things.

From the perspective of the community stakeholder, equitable power sharing processes are influenced heavily by funding structures that are important to be considered.

“That’s some unequal footing right there”: Sharing Resources Equitably

Community stakeholders spoke about the number of resources and capacity required to engaged in CEnR. Given limited organizational capacity, community stakeholders identified inequitable distribution of funds in CEnR as a challenge, primarily due to the high indirect percentage cost from universities. As an alternative, community stakeholders recommended to “level the playing field” and build the capacity of community partnerships by changing these percentages:

I think that research institutions, definitely can do more to build the capacity of community partners, you know, in terms of grant writing, how to put together a budget for research project, how can you support financially, because it takes resources to do community engagement work, but the university has a very high indirect percentage, you know even indirect cost percentage, and then the community based organizations no more than 10% whatever… so again that’s some unequal footing right there. So, you know if there’s a way to level the playing field and to give better percentages for indirect costs that the community partners can bill for the project that will be better.

Moreover, community stakeholders highlighted the importance of revising the language of university and academic partnerships contracts to focus on deliverables and promote community stakeholders’ autonomy and ownership.

… I think it’s also a tension between, like, how are those contracts perceived, and I think that it’s important that for community partners, to NOT be employed as individuals in a project where it’s like, you know, the project is supervising you and what, how, and your hours. But it should be more [of] a contract where you're responsible for certain deliverables and that gives the community organization more autonomy over how it achieves that.

Community stakeholders discussed possible alternative structures and systems that could increase community’s ownership and autonomy while considering organizational capacity, resources, and norms.

“You want to give people the tools to act”: Rethinking Research Ethics Training

Community stakeholders noted the need for research trainees to be thinking beyond traditional human subjects’ research ethics training. Major ethical issues identified stemmed from incongruent goals, power imbalances, and limited understanding of community’s history. Rather than defining research ethics based on participant protections and scientific integrity, community stakeholders highlighted the importance of CEnR researchers’ commitment to an expanded set of community-driven research ethics that includes honoring community partners’ ownership, being accountable in addressing power imbalances, and applying research into action. Partners noted that using resources inefficiently and distributing them inequitably would be unethical, contributing to tensions. As such, participants suggested that project management in these projects are vital. Moreover, community stakeholders suggested institutional changes to promote equitable distribution of resources. Additionally, CTSI training should encompass best practices around project management and translational science for researchers. One community stakeholder described “best practices around project management, managing a group, convening a group… I think some type of training around that is super helpful.”

Furthermore, community stakeholders also described translating research into action as a continuous area of growth for researchers: “Academics don't really, when you’re doing research to action, you want to give people the tools to act.” This was evident even in CEnR and participatory approaches to research. One community stakeholder stated: “I would just say that the one thing that gets lost, especially in things like CBPR is there’s a lot of focus on the research and not a lot of focus on the action.” To mitigate this issue, community stakeholders suggested researchers to develop and implement research dissemination skills that reflect a critical awareness of how to communicate effectively with multiple audiences. One community stakeholder raised thoughtful questions: “Sharing the information out… how do you make this available for an audience who are policymakers? How do you make it available to an audience for just like your typical community member thinking through?”

Similarly, interviewees suggested that researchers need to be trained to value community’s expertise and actively engage with the communities involved in the project through listening, learning, and contextualizing the histories of communities. Ethically speaking, researchers should take the time to learn about communities they aim to partner with and work in.

I think it’s important to also have researchers learn about communities and not just kind of like learning and becoming familiar with the community that they're working with, but also starting to understand what it is that the community partners themselves are doing and how the project fits into the community partners' own goals and agenda ….that piece of understanding the priorities and strategies and of the community partners is important because out of that conversation it’s also possible that new possibilities for partnership might come …. Otherwise, it’s usually driven by the academics.

In addition to having an orientation to action and critical awareness on community partners’ work, interviewees raised questions on sustaining partnerships with limited resources beyond the completion of the collaboration as a major ethical issue to consider.

So, I think how the accountable equitable partnerships is super helpful, I think some level of history of the Community. Right, that is like, knowing understanding what the community is working with, and you never gonna get the full history, but thinking about how to approach gatekeepers…Sustainability, what does that mean, and how to plan for it from day one. How do you plan for sustainability program, even if the funding goes away?

Researchers taking the time to fully engage with the community was seen a way to ensure the responsibility of educating and informing the academics involved in the research is not the sole responsibility of the community stakeholders. It was also seen as a way to help research academics approach community stakeholders with an informed lens able to add to the partnership, as opposed to simply extracting local knowledge. One community stakeholder stated: “So, I think it’s [mutual learning] is a critical part of training… how it happens, where the folks, the community who is doing the education gets as much out of the educational process as the person receiving the education.”

As indicated earlier in the discussion about positionality, interviewees emphasized the importance of approaching community partnerships with cultural and intersectional introspection which can help researchers, particularly those in charge of steering the projects, to understand the realities from which the different stakeholders are approaching the project and how this impacts the power dynamics within the collaboration team. This was also seen as an ethical issue in that failure to recognize positionality can reinforce the dominant narrative, causing further harm in communities.

…but the thing is you can interact with the population and not really fundamentally understand how much a large part of this community has been disempowered and been marginalized and then you kind of come in, in a way… that really serves to reinforce that and not really recognize that, essentially, you're part of that exploitation. If you don't look at it in a way and say, I'm going to be different in the sense that I'm looking to have a true partnership and I recognize fundamentally that there’s a value in these individuals and these partners that have worked for me and my approach from day one is coming in. I'm bringing a certain skill set. I understand and believe these partners I'm working with also have skill sets and I value back…. If you bring that from the front, from the beginning, then that really shapes the interaction and the value … But, if you say it, but you don't really act it, you don't mirror it then it gets lost, it’s a wasted opportunity.

In their own words, community stakeholders highlighted researchers need to have critical awareness “from the beginning” about health inequities in disadvantaged communities within the context of historical, racial, and structural determinants of health. In addition to relevant knowledge and understanding, community stakeholders suggested researchers to integrate concrete actions and changes to their research approaches that disrupt the cycle of exploitation.

Discussion

Meaningful, authentic, and equitable CE in clinical and translational science is essential to improve the health and well-being of communities [Reference Duran, Oetzel and Magarati47]. To accomplish this, education and training opportunities grounded in CEnR core competencies and community priorities are indispensable to ensure that researchers are well prepared to address challenges and to establish successful CEnR partnerships and collaborations.

Through this study, the CTSI CE core gathered and analyzed community stakeholders’ perceptions on CEnR training priority areas for researchers to inform the development of a graduate level course. Importantly, results from interviews with our partners add critical insight to the training needs of CEnR scholars. Findings suggest four key training areas of focus: (1) critical examination of researcher’s positionality, (2) revisit the centrality of relationship building and sharing power equitably in partnerships, (3) building community stakeholder’s capacity and funding support, and (4) CEnR ethics working with community partners. This study contributes to scholarly literature relevant to the development of CEnR training curriculum from the perspectives of community stakeholders in CEnR partnerships.

Our findings are consistent with the literature that highlights the need for training academic researchers on equitable community partnerships [Reference Ziegahn, Joosten and Nevarez48]. Findings of a systematic review of online CEnR resources from all CTSAs between 2018 and 2019 found that major areas of domain address across online resources included CEnR methods and knowledge and relationships with communities [Reference Piasecki, Quarles and Bahouth49]. Community stakeholders in our study emphasized the importance of having a critical examination of personal biases due to its potential impact on relationships and the collaboration. Moreover, interviewees highlighted the centrality of integrating an orientation to action and sustainability of the partnership even beyond the completion of the research project. This is a domain of continuous discourse, particularly when academic partners have focused primarily on traditional research outcomes, whereas community stakeholders have discussed the importance of committing to a long-term, ongoing relationship beyond the project scope when funding and resources are no longer available [Reference Alexander, Sullivan and Joosten50].

Doberneck and colleagues [Reference Doberneck, Bargerstock, McNall, Van Egeren and Zientek51], in developing CE competencies for graduate and professional students identified “Criticality in Community Engagement” as a key competency. Criticality was defined as the ability to identify positionality and reflect critically on how one’s own position impacts relationships. This was seen to ensure that oppressive systems are not replicated in the context of the partnership by grappling to the inequitable distribution of power. Building the capacity for critical reflection allows learners to engage in difficult dialog in a meaningful way, deepening relationships with partners, and strengthening their commitment to research that advances structural change. Similarly, Coffey et al. [Reference Coffey, Huff-Davis and Lindsey52] in developing community-led workshops for researchers relied on popular education which is steeped in critical pedagogy, which challenges learners to critically reflect on root causes and to act collectively. In the process of combatting personal biases, discrimination, and racism, research suggests ongoing individual and collective reflexive praxis that combines critical reflection and critical action as relevant tools for CEnR partnerships to promote equitable decision-making and discussion of common areas of concern [Reference Roche, Shimmin and Hickes53,Reference Wallerstein, Oetzel and Sanchez-Youngman54].

Inequities in resource distribution remain a challenge for partnerships. Institutional funding practices and mechanisms, particularly at the university level have been discussed in the literature. Some include small size of grants as well as administrative, academic, and financial roadblocks such as institutional review board approval process, contracting and disbursement of funds, and lack of salary support [Reference Kegler, Blumenthal and Akintobi55]. Training opportunities to increase knowledge and understanding of scholars and students to tackle these challenges remain limited and scholarly evidence suggests adopting long-term sustainable training strategies, systems, and supports to address these gaps [Reference Warren, Park and Tieken56]. Research suggests increasing knowledge of the process of subcontracts, communicating clearly fiscal responsibilities of the grant and budget allocation, and establishing mechanisms to expedite subcontract payments at university levels as potential strategies to overcome barriers to executing successful community subcontracts and achieve equitable resource sharing in CEnR partnerships [Reference Huff-Davis, Cornell, McElfish and Kim Yeary57]. In summary, findings are consistent with scholarly evidence that underscore the importance of considering multilevel approaches to address financial inequity within CEnR including both, 1) changing inflexible institutional policies that prevent equitable distribution of funding, and 2) training scholars to be accountable in their roles to name, challenge, and shift power hierarchies [Reference Shoultz, Oneha and Magnussen58,Reference Mohammed, Walters, LaMarr, Evans-Campbell and Fryberg59]. These findings also inform the work of the CTSI CE core by considering iterative series of training offerings to various audiences including students, trainees, and community stakeholders on centering equity in the grant writing process to build relevant financial capacity, knowledge, and skills. While prospective CEnR scholars, students, and trainees may not necessarily have direct control over existing institutional policies and mechanisms that contribute to inequitable distribution of funds and power differentials, students and trainees in the CEnR course can engage in various short-term and long-term foundational initiatives to deepen their awareness on navigating complex financial structures, develop relevant skills, and contribute to institutional changes to advance the spectrum of participation and achieve transformative changes that promote equity [Reference Salerno, Coleman, Jones and Peters60].

In general, findings of the study validate existing CEnR competency frameworks and shed light on critical nuances to consider. Interviewees’ generated recommendations to strengthen CEnR training priorities, particularly on establishing collaborative decision-making processes, are in alignment with Shea and colleagues’ [Reference Shea, Young and Powell13] CEDI domains and competencies that assess researchers’ readiness levels to engage in equitable partnerships. However, major distinctions emerge when analyzing interviewees’ feedback in comparison with existing CEnR competency models. Interviewees highlighted how individual actions, behaviors, and attitudes can be insufficient to develop equitable collaborations, particularly when these processes are shaped by structural and institutional factors. In addition to integrating multilevel approaches to CEnR competencies, findings also underscore the ways CEnR partnerships should observe the centrality of action-driven initiatives to inform policy and practice. Overall, findings validate existing CEnR competency frameworks and suggest expanding multiple CEnR competency domains for researchers to engage in a continuous and ongoing learning journey. Further research should explore comparative analyses of community stakeholders’ perceptions and existing competency frameworks to build a model that includes these nuances.

Our study is limited by a small sample size of community stakeholders. It is possible that the group of community partners interviewed are not representative of all community stakeholders engaged in CEnR partnerships and therefore, findings are not generalizable. Community partners interviewed were recruited primarily through CTSI CE core members’ personal networks and relevant data on the CEnR partnership was not captured. While this sampling strategy contributed to gathering data within a relevant geographic and research-specific context pertaining to university faculty, researchers, and CTSI CE core team, findings are not generalizable given the sampling strategy used and the small sample size. Relevant nuances of CEnR partnerships across multidisciplinary fields may not have been documented. Further studies should recruit multilevel stakeholders engaged in CEnR partnerships across local and national established networks and capture additional information on organizational capacity, CEnR partnership length, and field discipline of projects engaged.

Despite these limitations, this study identifies critical domains of training for CEnR scholars from the perspective of community partners, a voice underrepresented in clinical and translational research and training. A key recurring recommendation from community partners was to acknowledge that both research collaborations and their goals are dynamic. This can serve a two-fold purpose: (1) ensuring that resources and expertise of various stakeholders are being utilized efficiently throughout the span of the collaboration and (2) it can prevent tensions from rising out of conflicting perspectives and expectations. Hence, throughout the course of the partnership, it is important to continue aligning various stakeholders’ goals with the broader scope of the project through continuous and sustained communication.

Conclusion

Developing CEnR training curriculum in partnership with community stakeholders can increase scholars’ capacity to build meaningful and equitable CEnR partnerships because of its potential for highlighting overlooked areas of tension and continuous areas of growth. Findings of this study are well aligned with multilevel and complex challenges CEnR partnerships experience within community-based research collaborations when funding inequity, labor, and hierarchical power dynamics are considered. Further research should be conducted to explore and evaluate CEnR scholars’ competencies from the perspectives of key community stakeholders to inform training curriculum and advance the science of CE. Moreover, community-engaged approaches to pedagogy and CEnR training development present relevant implications to inform policy. Involving community stakeholders in critical discussions and examinations of how university’s structures and policies can better align with CEnR principles towards creating equitable community–academic collaborations which has the potential to identify structural barriers and potential solutions to systems reinforcing inequity and dominant worldviews steeped in white supremacy. Finally, CE can enhance research training, policy, and practice. This can only happen when scholars achieve relevant CEnR competencies towards building equitable and meaningful partnerships through the development and application of relevant knowledge and best practices that reflect critical awareness of researcher’s positionality and power differentials while valuing community expertise and promoting community ownership and autonomy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank each of the community stakeholders who contributed their valuable expertise to the development of this manuscript. This study was supported by the National Center to Advance Translational Science, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL54TR004130. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the office views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Linda Sprague Martinez is an evaluation consultant for the Boston Public Health Commission. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.