Childhood obesity has increased dramatically during the past decades, both in developing and developed countries( Reference Wang and Lobstein 1 , Reference de Onis, Blössner and Borghi 2 ). In 2009–2010, 18·2 % of US children and adolescents aged 6–19 years were obese( Reference Ogden, Carroll and Kit 3 ). As a populous country, it was estimated that 5·1 % of Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years were obese in 2010( Reference Ji and Chen 4 ). Therefore, the worldwide prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents, with its attendant health risks, has become an important public health concern( Reference Franks, Hanson and Knowler 5 , Reference Karnik and Kanekar 6 ).

BMI is perhaps the most commonly used measure for defining overweight and obesity in clinical practice and population surveys. However, BMI cannot distinguish between fat and fat-free mass; it provides no information on body fat distribution. Several studies have shown that compared with BMI, the amount and distribution of body fat play a greater role in the development of obesity-related complications such as CVD and type 2 diabetes( Reference Despres 7 ). A number of different tools and methodologies have been developed to measure body composition, of which skinfold thicknesses (SFT) have been shown to be closely correlated with total body fatness( Reference Mei, Grummer-Strawn and Wang 8 – Reference Addo, Pereira and Himes 10 ). Furthermore, SFT measurements are non-invasive, simple and less expensive than laboratory-based techniques, so they have been widely applied in large-scale epidemiological studies.

Shandong Province, located in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, facing Japan and the Korean Peninsula to the east, is an important littoral province in East China. Secular trends in BMI and the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in this region have been documented in previous studies( Reference Zhang and Wang 11 , Reference Zhang, Zhao and Chu 12 ). In the present article, we report the trends in the prevalence of elevated SFT among children and adolescents over the last 19 years (1995–2014) in Shandong, China.

Participants and methods

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Shandong Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shandong, China.

Study population

Data for the present study were obtained from two national surveys on students’ constitution and health carried out by the government in 1995 and 2014 in Shandong Province, China. A total of 16 917 students, aged 7–18 years, of Han nationality in Shandong Province were included in the study (7198 in 1995 and 9719 in 2014). The sample size of age groups of each survey is given in Table 1. There were 299 to 427 participants in each of the age and sex groups in different years. The sampling method was stratified multistage sampling based on socio-economic status, drawn from three citiesFootnote * as survey districts, and using randomly selected primary and secondary schools, the sample proportions in these three districts in each survey were equal. Six public schools (two primary schools, two junior high schools and two senior high schools) from each of the three districts in Shandong were randomly selected and invited to participate in the survey. From the selected schools, two classes in each grade were selected and all students of the selected classes were invited to join the study with informed consents. All participants were primary- and secondary-school students, ranging from 7 to 18 years of age, and all were of Han ancestry that accounts for ~99·32 % of the total population in Shandong. Most importantly, the schools from which the participants were sampled were relatively stable since 1995, and the method and quality control of measurements of the two surveys was the same.

Table 1 Prevalence of ‘high SFT’ (sum of triceps and subscapular skinfold thickness above or equal to the national age- and sex-specific 85th percentile) among children and adolescents aged 7–18 years, Shandong Province, China (n 16 917), in 1995 and 2014

Difference between 1995 and 2014: *P<0·05, **P<0·01.

Measurements

All measurements were performed by well-trained health professionals in each of the three districts using the same type of apparatus and following the same procedures. SFT were measured on the right side of the body using a skinfold calliper (Minjian model GMCS-PZQ; Beijing Xindong Huateng Sports Instruments Company, Limited) to the nearest 0·5 mm, at two sites: (i) triceps, halfway between the acromion process and the olecranon process; and (ii) subscapular, 1·0 cm below the inferior angle of the scapula, at an angle of 45° to the lateral side of the body. In each participant, three measurements were taken, and the middle value was recorded for one skinfold site. The sum of triceps and subscapular SFT (SSFT) was applied.

Statistical analyses

Children and adolescents with SSFT above or equal to the national age- and sex-specific 85th percentile( 13 ) were defined as ‘high SFT’. Prevalence rates of ‘high SFT’ were determined, with comparisons between 1995 and 2014 made by the χ 2 test. All analyses were performed with the statistical software package SPSS version 11.5. Significance was defined at the 0·05 level.

Results

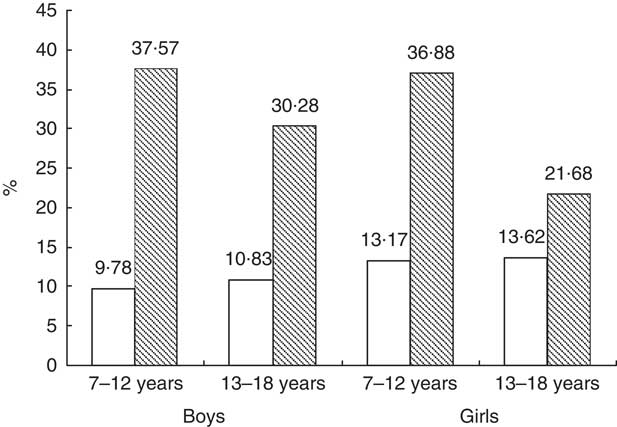

The prevalence of ‘high SFT’ among children and adolescents by gender and age categories in 1995 and 2014 is shown in Table 1. The χ 2 test indicated that the prevalence of ‘high SFT’ surveyed in 2014 was significantly higher than that in 1995 in all age groups (P<0·05 or 0·01). The overall prevalence of ‘high SFT’ increased from 10·31 % (boys) and 13·40 % % (girls) in 1995 to 33·94 % (boys) and 29·30 % (girls) in 2014 (P<0·01). The prevalence of ‘high SFT’ by gender and age stage is shown in Fig. 1. During the 19-year period, for children (aged 7–12 years), the prevalence of ‘high SFT’ increased by 27·79 (boys) and 23·71 (girls) percentage points (from 9·78 % for boys and 13·17 % for girls in 1995 to 37·57 % for boys and 36·88 % for girls in 2014), while for adolescents (aged 13–18 years), ‘high SFT’ prevalence increased by 19·45 (boys) and 8·06 (girls) percentage points (from 10·83 % for boys and 13·62 % for girls in 1995 to 30·28 % for boys and 21·68 % for girls in 2014), respectively, indicating that the increment was bigger in children than in adolescents.

Fig. 1 Prevalence of ‘high SFT’ (sum of triceps and subscapular skinfold thickness above or equal to the national age- and sex-specific 85th percentile) in children (aged 7–12 years) and adolescents (aged 13–18 years), Shandong Province, China (n 16 917), in 1995 (![]() ) and 2014 (

) and 2014 (![]() )

)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first examining the trends in the prevalence of elevated SFT among children and adolescents over the last 19 years in Shandong, one of the populous provinces in China. We found that there are more children and adolescents with very high levels of SFT; these trends describe very unfavourable changes in the body composition and should give cause for concern.

Body fat increases when energy intake is consistently greater than energy expenditure. In China, the rapid economic growth has led to changes in dietary and physical activity patterns, including an increase in the consumption of energy-dense foods and a decrease in physical activity( Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng 14 , Reference Du, Bennett and Li 15 ). These changes in lifestyle may play an important role in the observed increases in SFT reported here. Our results are in accordance with findings from other studies( Reference Olds 16 ).

In the current study, we found that the prevalence of ‘high SFT’ among children and adolescents had a rapid increase in the past 19 years, supporting other analyses based on BMI, which show a rapid increase in the prevalence of overweight and obesity( Reference Ji and Chen 4 , Reference Zhang and Wang 11 , Reference Zhang, Zhao and Chu 12 ). The increasing prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity may be attributed to a markedly changed lifestyle associated with inactivity and dietary habits. Chinese diets have changed vastly in the last decades. The traditional diet, in which plant foods were given priority, has been replaced by the ‘Western diet’, which is broadly defined by high intakes of refined carbohydrates, added sugars, fats and animal-source foods( Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng 14 ). Some researchers suggested that the rapid development of the Western fast-food market (such as McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken) and physical inactivity are the two major predisposing factors for increasing prevalence of childhood obesity( Reference Cheng 17 ). The first Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonald’s restaurant opened in China in 1987 and 1990 respectively, and now there are more than 2000 McDonald’s (http://www.mcdonalds.com.cn/index/McD/about/company) and 5000 Kentucky Fried Chicken (http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KFC#Asia) outlets in the country. Chinese children well recognize the images of McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken and like to eat Western fast foods. Furthermore, some parents will even use these junk foods as a reward for their children. Chinese children are under great pressure to achieve scholastically, so they usually spend a lot of time doing homework instead of gymnastic exercises and sports activities( Reference Tudor-Locke, Ainsworth and Adair 18 , Reference Tudor-Locke, Ainsworth and Adair 19 ). In addition, the activity patterns of children have shifted from outdoor play to indoor entertainment: television viewing, Internet and computer games( Reference Popkin 20 ). Fortunately, the Chinese Government has realized the importance of obesity control and of playing a leading role, with the introduction of laws and regulations aimed at obesity prevention. For example, the Ministry of Health released the Nutrition Improvement Work Management Approach in 2010 to promote national nutrition initiatives and to enhance the nutrition and health status of Chinese residents( Reference Wang and Zhai 21 ). A new policy of one hour of physical activity in schools every day was mandated by the Ministry of Education in 2011, which has had a beneficial effect in preventing obesity in adolescents( Reference Zhang, Zhou and Zhao 22 ).

We also found that children (aged 7–12 years) showed a more rapid increase in the prevalence of ‘high SFT’ than adolescents (aged 13–18 years) between 1995 and 2014. The reason is still unclear but may be related to the difference in lifestyle and dietary patterns between the two age stages; compared with children, adolescents generally pay more attention to their body shape and engage in more physical activity( Reference Zhang, Seo and Kolbe 23 ).

Two limitations should be noted. First, data for the present study were acquired from two independent cross-sectional surveys spanning 19 years rather than from a longitudinal cohort study, thus preventing further assessment of cohort and time effects. Second, the absence of detailed information concerning living environments, dietary patterns and physical activity at the individual level also limited our study.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The surveys on students’ constitution and health were conducted under the auspices of the Department of Education in Shandong Province, China. The authors thank all the team members and all participants. Special thanks go to Mr B. Yu for providing access to the survey data. Financial support: This study was supported by the Medical and Health Program of Shandong Province, China (2014WS0376). The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest on behalf of any of the authors. Authorship: S.-R.W. performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript, Y.-X.Z. designed the study and gave instructions on data analysis, Y.C. and M.C. helped with data collecting and sorting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Shandong Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shandong, China.