INTRODUCTION

In this article I argue that eminent domain should be understood not only as an involuntary individual loss of property for public use, but also as a kind of government expenditure that redistributes property for the public’s good. Hence, one might posit that this form of public expenditure would follow the same distributional patterns as does direct spending, disproportionately imposing the burden to supply public goods on politically weak minority communities and landowners. Through an empirical study of eminent domain in Jerusalem, I argue that the standard constitutional protection of property rights ignores the community or group aspect of land, and thus enables the state excessive power that may be employed to the detriment of minority communities, even in cases where their dispossession is unintentional and subject to common protections such as due process and fair market value compensation.

A large-scale comparative study shows that governments across all legal traditions have the constitutional power to seize property when it is required for the public good (Versteeg Reference Versteeg2015), as long as just compensation (of fair market value) is available to the aggrieved owner (Lindsay, Deininger, Hilhorst Reference Lindsay, Deininger, Hilhorst, Kim, Lee and Somin2017). The constitutional takings power is usually justified in that it enables the government to overcome strategic bargaining problems such as holdout and land assembly to acquire land needed to provide public goods (Miceli Reference Miceli2018; Kelly Reference Kelly, Ayotte and E. Smith2011). Theoretically, at least, the harm suffered is fully redressed by compensation to the individual, while the public use requirement supposedly mitigates the concern that the land is taken to benefit a privileged private party. The enormous volume of literature on constitutional taking focuses on that model, i.e., what should be considered proper “just compensation” and “public use” (see, e.g., Stern Reference Stern2019).

The empirical data presented in this article points at the weaknesses of existing constitutional property protections to sufficiently ensure the cohesion and prospects for future development of minority communities facing the risk of constitutional taking. When one flips the perspective from focusing on the harm that an expropriation decision causes the individual to that suffered by the community, the potential abuse of power, racism, and dispossession become starkly apparent, even if all existing legal requirements have been met. While this claim may be intuitively appealing, it is very hard to test and hence the novelty of this study.

A notable example of racial discrimination through constitutional taking is the razing of African-American neighborhoods for the construction of interstate highways or purported “urban renewal” in the 1950s and 1960s. The properties of the poor or minority communities were crushed under the wheels of “transportation modernization” (see, e.g., Frieden and Sagalyn Reference Frieden1991; Gans Reference Gans1982) and the recreation of American cities (Joo Reference Joo2017; Sugrue Reference Sugrue2014; Avila and Rose Reference Avila and Rose2009; Gotham Reference Gotham2001). While many suspect that this discrimination was intentional, even assuming that policymakers were not racially motivated, group-level discrimination may nonetheless be the outcome (Lippert-Rasmussen Reference Lippert-Rasmussen2014, 59–60). Absent evidence of intentional discrimination, courts are unlikely to block takings on the grounds of racial discrimination. In the American context, for example, there have not been thus far “direct cases involving the use of eminent domain for a solely discriminatory use” (Tierney Reference Tierney2019, 187); and in other contexts, such as the Israeli one, only clear and direct legislative efforts toward discriminatory expropriation were invalidated (Hostovsky Brandes Reference Hostovsky Brandes2020).

Identifying the discriminatory nature of eminent domain activities when they are not prima facie discriminatory requires highly rich longitudinal data that can reveal hidden patterns. A unique institutional situation in Jerusalem allows me to create such a dataset. For historical and political reasons, mainly the one-sided annexation of Palestinian parts to Jerusalem after the 1967 War, Jerusalem exhibits an extremely high degree of segregation: Jews and Palestinians live in separate neighborhoods, with differing education systems and above all differing civil statuses. In addition, the Palestinian communities have limited political influence. Most East Jerusalem Palestinians lack citizenship and therefore do not exercise their municipal voting power, and they generally avoid alternative forms of asserting their collective rights against the local government, such as political protest (Blake et al. Reference Blake, Bartels, Efron and Reiter2018). They are thus “practically invisible to the Israeli planning authorities,” according to some (Rosen and Charney Reference Rosen and Charney2016, 169), and, as others argue, subject to dispossession and displacement through a complex mechanism hidden behind seemingly innocuous planning laws and mundane bureaucratic procedures (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2016b, 190; Braverman Reference Braverman2007).

My interdisciplinary investigation aims to translate empirical social science into the actual practices of constitutional taking for legal professionals while also translating the constitutional taking law and dynamics for social scientists (Erlanger et al. Reference Erlanger, Garth, Larson, Mertz, Nourse and Wilkins2005). I compiled and coded handwritten minutes and files from the city archives, as well as official public records, on all proceedings of eminent domain for local public uses by the city from 1990–2014. In that period, the city exercised its taking powers over 369 development projects, which include 3,448 discrete taking observations. I used land records to verify owners’ identity; analyzed comprehensive plans and zoning maps to identify the communities benefiting from the subsequent projects; conducted interviews with local officials; conducted GIS analysis of land cover, status of land registration, and demographic patterns; and drew on supplementary statistical and geographical resources.

The empirical analysis reveals a correlation between the ethnoreligious and political divide between Palestinians and Jews in Jerusalem and their burden:benefit ratio under constitutional takings used to provide strictly public goods such as roads, parks, and public buildings. It concludes that Palestinian owners’ land is prone to being taken significantly more than their proportion among property owners, and for uses that do not directly benefit their communities. This is especially apparent with respect to the allocation of quality-of-life-enhancing public works such as parks, playgrounds, and schools.

In addition, the data reveals the clear effect of weak property rights on the propensity to have one’s property taken for noncommunity uses. As the national process of formal land recording was not undertaken in some parts of Palestinian Jerusalem, this case study enables distinguishing between randomly registered and nonregistered Palestinian properties. The regression analysis shows that nonregistered land claimed by the politically weak minority is significantly more susceptible to being taken for noncommunity uses than is any other land category. Consequently, where formal land records do not exist, the risk of redistributive discriminatory expropriation is much higher than that faced by formally recorded owners. While this outcome contradicts the conventional wisdom that weak property rights help explain limited infrastructure investment (Cai, Murtazashvili, and Murtazashvili Reference Cai, Murtazashivili, Murtazashvili and Wang2020; Uribe Reference Uribe2017; Davidson Reference Davidson2015; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Trebilcock and Veel Reference Trebilcock and Veel2008), it is consistent with newer studies that question the relationship between property protections and development (Holland Reference Holland2019; Vahabi Reference Vahabi2016).

DISTRIBUTION OF THE TAKING BURDENS AND BENEFITS ACROSS POLITICAL COMMUNITIES

In standard law and economic literature, eminent domain power is distinguished from the tax and transfer system in that the latter is aimed at redistribution as per substantive policy formulation, while the former is not. Compensation for land taking is therefore “thought to promote the equitable distribution of burdens throughout a community by avoiding the taking’s distributional effects” (Kaplow Reference Kaplow1986, 519). Extensive theoretical scholarship has been devoted to examining whether the eminent domain system works, i.e., whether the just compensation and public use requirements indeed impose fair and efficient limitations on the taking power. Empirical studies, however, are still quite limited, as “eminent domain has proven difficult to study due to severe data constraints” (Kitchens Reference Kitchens2014, 456; for a review of empirical studies, see Atuahene Reference Atuahene2016b).

A few notable exceptions focus on the outcomes for owners, especially in terms of compensation for forced taking (Portillo Reference Portillo2018; Kitchens Reference Kitchens2014; Chang Reference Chang2010; Munch Reference Munch1976), and on reactions to eminent domain among legislators (Morriss Reference Morriss2009; Nadler and Diamond Reference Nadler and Seidman Diamond2008) and the public (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Murtazashvili and Murtazashvili2020; Metcalf Reference Metcalf2014; Becher Reference Becher2014).

In the theoretical scholarship, the just compensation requirement has been justified on efficiency grounds, based on the assertion that government officials ignore costs that their actions impose on private parties as long as they do not affect their budget. The need to compensate the private owner supposedly remediates this “fiscal illusion” problem (Blume, Rubinfeld, and Shapiro Reference Blume, Rubinfeld and Shapiro1984). This assertion has been criticized. Some writers suggested that decision makers do not respond to budgetary considerations but rather to political ones. Hence, the price mechanism provided by the compensation requirement does not reflect the entire set of relevant costs (and considerations) entailed in taking decisions (Levinson Reference Levinson2000). This claim has been supported by recent empirical studies that show that government officials are less responsive to budgetary maximization considerations, especially compensation costs, than had been assumed by the fiscal illusion hypothesis (Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky Reference Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky2016; Chang Reference Chang2009).

The fairness of the compensation mechanism has also been questioned. Some argue that fair market value compensation is not sufficiently “just” unless the subjective value and other considerations are taken into account, while others disagree (see e.g., Fennell Reference Fennell2013; Lee Reference Lee2013; Wyman Reference Wyman2007; Bell and Parchomovsky Reference Bell and Parchomovsky2006). In addition, in rare examples of attention to the aspect of community in the expropriation context, it has been stressed that monetary compensation does not compensate for loss of community associated with takings (Stern Reference Stern2014; Parchomovsky and Siegelman Reference Parchomovsky and Siegelman2004).

In the past decade, increasing judicial and scholarly attention has been devoted to the question of who wins and who loses in cases of takings for economic development (Somin Reference Somin2015, 228; Hoehn and Adanu Reference Hoehn and Adanu2014; Nadler and Diamond Reference Nadler and Seidman Diamond2008; Garnett Reference Garnett2006; Boudreaux Reference Boudreaux2005).Footnote 1 In particular, recent studies support the common claim that in the American context, African-Americans and other minorities bear the burden, but not the benefit, of economic development projects (Werkneh Reference Werkneh2017). At least in some cases, this is considered to be the outcome of a deliberate effort to clear “slums” or “underdeveloped” properties held by members of these communities (Somin Reference Somin2015; Becher Reference Becher2014; Carpenter and Ross Reference Carpenter and Ross2009; Frieden and Sagalyn Reference Frieden1991; Gans Reference Gans1982).

To date, however, no study has systematically questioned the community-level distributional aspect of takings for strictly public, rather than economic-development, purposes. Specifically, no prior research has managed to correlate owners and beneficiaries of land takings. Hardly any study has sought to test the question of whether such takings induce parity or deepen disparity across political and ethnoreligious lines. This might be due to the difficulty of constructing a benchmark of what an unbiased allocation of burdens and benefits would look like (Kasara Reference Kasara2007); and the risk that identifying a pattern of favoritism with respect to one outcome might be counterbalanced by another, even opposite pattern of favoritism with respect to other, unmeasured outcomes (Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2013).

In an important contribution, Chen and Yeh (Reference Chen and Yeh2012) examined the effects of pro-taking court precedents. They reported that court decisions that expanded the government’s power of expropriation spurred economic growth and property prices by 0.2 percent, but reduced racial minorities’ home ownership and employment by 0.5 percent and 0.3 percent, respectively. Their study did not distinguish, however, between pro-taking decisions regarding takings for strictly public purposes (roads, public spaces, public buildings, etc.) and decisions regarding economic development purposes (such as for residential or commercial uses), but rather mostly documented the effects of the latter. Furthermore, Chen and Yeh’s methodology was limited in that they did not study the direct distribution of the taking burden or the various levels of benefit from the public goods facilitated thereby.

I contend that eminent domain should be observed not only as an involuntary individual loss of property for public use, but also as a government expenditure that enables advancing redistribution of property for the public’s good. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is that politically weak communities will bear a disproportional burden of supply of public goods through eminent domain that will not be offset by the benefits of those goods.

To test the distributional effect of takings and observe the effect of sociopolitical and other differences on the distribution of burdens and benefits, we need to identify an environment with clear cross-community differences, a way to identify the communities burdened with contributing land and those that benefit from its taking, and the specific public uses for which it is taken. Below, such an environment is described: the case of expropriations in Jerusalem.

THE EFFECT OF WEAKLY VERSUS STRONGLY DEFINED PROPERTY RIGHTS ON OWNERS’ VULNERABILITY TO EXPROPRIATION

Identifying the effect of political power relations on the risk of expropriation requires understanding the effect of weak property rights on that risk. As several studies have shown, selective protections of property rights that track power relations are common (Cai, Murtazashvili, and Murtazashvili Reference Cai, Murtazashivili, Murtazashvili and Wang2020; Greif Reference Greif2006; Haber, Maurer, and Razo Reference Haber, Maurer and Razo2003). This is also the case with Jerusalem, as some parts of city which are resided in by Palestinians, are deliberately among the only locales that have yet to be included in the official land registry that was executed by the Israeli government across the country. The existence of areas with and without land records in one city enables studying the effect of weak versus properly defined property rights on the propensity to being vulnerable to aggravated harm by eminent domain.

An extensive new institutional economics literature advances the importance of properly defined and enforced property rights (North and Thomas Reference North and Thomas1973, 3), emphasizing the virtues of formal title to capitalize on land possession (De Soto Reference De Soto2000). The accumulated evidence on the outcomes of land titling efforts worldwide is rather mixed and puzzling, and there are ongoing debates on whether, in various jurisdictions, their economic benefits outweigh their costs and their distributional impact (Leeson, Harris, and Myers Reference Leeson, Harris and Myers2021; Perego Reference Perego2019; Hornbeck Reference Hornbeck2010; Besley and Ghatak Reference Besley, Ghatak, Rodrick and Rosenzweig2009; Field Reference Field2007; Deininger and Chamorro Reference Deininger and Sebastian Chamorro2004; Glaeser et al. Reference Glaeser and Porta2004; Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Binswanger-Mkhize, Deininger, and Feder Reference Binswanger-Mkhize, Deininger, Feder, Behrman and Srinivasan1995; North Reference North1981, 198). The consensus is that the impact of titling is highly context specific (Atuahene Reference Atuahene2016b, 183).

The basic theoretical premise in political economy is that property rights, well defined and enforced, provide incentives for undertaking socially beneficial activities by the owners, and allow avoiding the “tragedy of the commons” (Demsetz Reference Demsetz1967). As North and Thomas argued, the mechanism of property rights is required to “bring social and private rates of return into close parity” (1973, 2). The conventional wisdom is therefore that weak property rights help explain limited infrastructure investment (Cai, Murtazashvili, and Murtazashvili Reference Cai, Murtazashivili, Murtazashvili and Wang2020; Uribe Reference Uribe2017; Davidson Reference Davidson2015; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). Well-defined property rights are essential for economic development, through two complementary mechanisms: They incentivize private sector investments, and they lower transaction costs (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Besley and Ghatak Reference Besley, Ghatak, Rodrick and Rosenzweig2009; North and Thomas Reference North and Thomas1973). Writers such as Scott (Reference Scott1998, 36) and Katz (Reference Katz2012) further argued that governments have an interest in creating a system of well-defined and well-recorded property rights to render owners more vulnerable to state power. Land registry, so the claim goes, expands government power in terms of enforcing taxation and norms (Leeson and Harris Reference Leeson and Harris2018 suggested that the process of formalization itself may be beneficial to government agencies overseeing it). Anecdotal case studies also reveal that knowing the identity of owners was crucial to accomplishing infrastructure projects (Holland Reference Holland2019; Uribe Reference Uribe2017, ch. 5; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012, 197), and that overall, countries’ wealth is correlated with property protections (Besley and Ghatak Reference Besley, Ghatak, Rodrick and Rosenzweig2009).

Contrary to this common wisdom, Behrer et al. (Reference Behrer2021) argued that formal ownership does not necessarily enhance government power: It can also place limits thereon. Without institutional constraints on the state’s ability to intervene with property rights, political officials are prone to exploiting their power (Boettke and Candela Reference Boettke and Candela2020). While there is a robust positive relationship between development and investment security, puzzlingly, there is likewise a negative relationship between investment security and state investment in infrastructure. Holland (Reference Holland2019) compared Colombia and Ecuador, countries that differ in their property rights protections against governmental taking, and demonstrated that where better protections exist, so do longer infrastructure delays. Arguably, well-protected property rights induce high transaction costs for infrastructure projects due to opportunistic behavior on the part of property owners. Holland thus correlates the level of owners’ expected opportunism with the level of protection provided by property rights using three dimensions of property rules: who owns property (state, individual, community); how compensation is assessed (objective/subjective value); and whether there is a right to appeal a taking decision and stall the project until its resolution. For instance, when the community owns the land, compensations are paid based on subjective value, and there is a substantive right of appeal, opportunistic behavior is expected to be higher, as indeed is observed in the cases studied.

In this article, I take a different approach that is not focused on the behavior of the affected parties (landowners, communities, strategic investors) in response to the government’s decision, but rather on the behavior of the deciding party, i.e., the government, that has to decide which infrastructure project to advance, where to locate it, and consequently, which land to forcefully acquire. I ask whether the government’s actions at the decision stage are informed by the level of property protection that is available to the potentially affected owners. In doing so, I utilize a case study that, under Holland’s (Reference Holland2019) terms, offers a statist system with the prediction of minimal opportunistic behavior on the owners’ parts. In this setting, properties’ values and accordingly the compensation for their taking are based on objective, administrative assessment. There is a right of appeal against expropriation decisions, but it is severely constrained, as the government does not have to secure a pre-taking agreement with the owner about the land’s valuation. This statist setting enables me to add another layer to that typology: the availability of trusted land records. I thus aim to offer a nuanced analysis of the specific effect of land formalization on the government’s taking behavior. Accordingly, Hypothesis 2 is that weak property rights—i.e., nonformalized land—will be more appropriable than will strong property rights—i.e., formalized land, and therefore subject to greater predation by the government. This is due to two related reasons: Firstly, the political and judicial limitations on abuse of power are weaker where there is ambiguity concerning the residual claimant of the land. Secondly, the value of nonformalized land is lower due to limited transferability and smaller investments therein (Dippel and Frye Reference Dippel and Frye2020). As a result, nonformalized land is more seizable by the state (Vahabi Reference Vahabi2016). Hence, by controlling the process of land formalization, the state can decide selectively which communities’ properties to register, thus enabling it greater scope for predation (Cai, Murtazashvili, and Murtazashvili Reference Cai, Murtazashivili, Murtazashvili and Wang2020).

To my knowledge, this hypothesis has not been studied heretofore. There is related literature that is focused on popular views on the perceived risk of expropriation by property owners depending upon their official status. For instance, Bezu and Holden (Reference Bezu and Holden2014) studied the decision to invest in purchasing formal title in Ethiopia, and noted that the fear of expropriation, which may be more pronounced on larger farms, may suppress willingness to pay for a land registration certificate. They explained that farmers fear that the elective outlay would be lost under conditions of a less-than-comprehensive compensation scheme, while the formal title would not provide them with additional security.

Others, however, have reached differing conclusions, providing qualified evidence for how the perceived risk of expropriation affects people’s behavior (Ghebru, Koru, and Taffesse Reference Ghebru, Koru and Seyoum Taffesse2016). Based on a study of unplanned urban settlements in Tanzania, Collin et al. (Reference Collin, Dercon, Lombardini, Sandefur and Zeitlin2012) found that the implementation of an infrastructure upgrading program had positive effects on the demand for land titles, thanks to both increase in land values and a higher perceived risk of expropriation—two mechanisms that the researchers could not uncouple. Most recently, Perego (Reference Perego2019) found that Ugandan farmers who perceived greater risk of land grabbing (which included all threats to rights, governmental or otherwise) became more willing to formalize their land tenure as crop prices rose. Pertinently, Dari-Mattiacci and Fabbri (Reference Dari-Mattiacci and Fabbri2021) reported that social preference for respecting others’ property increased for subjects who had experienced land titling reform. In this study, I therefore test which of these popular intuitions is better echoed in a given government’s actual taking behavior.

JERUSALEM: A TALE OF TWO CITIES

Following the 1967 War, the Israeli government unilaterally annexed an area of about 17,273 acres that was under Jordanian rule before the war (Jerusalem Statistical Book 2015; Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics 2014; Hoshen, Hason, and Kimhi Reference Hoshen, Hason and Kimhi2004; Hazan Reference Hazan1995; GIS analysis).Footnote 2 Commonly referred to as East Jerusalem, it includes the Old City and the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif, and was immediately incorporated into the City of Jerusalem’s jurisdiction (Dumper Reference Dumper2014). Only 10 percent of the annexed area had been part of Jordanian Jerusalem; the remainder contained villages and surrounding rural land. Following the annexation, Jerusalem was populated by 74 percent Jews and 26 percent Palestinians, compared to 99 percent and 1 percent respectively in pre-annexation (West) Jerusalem; over the years, the ethnonational gap narrowed, so that by 2014, it was 61 percent and 37 percent (Jerusalem Statistical Book, 2015).

Many consider the annexation illegal under international law, and it remains unrecognized by most countries. According to the International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion on the matter of the Separation Barrier, East Jerusalem is an occupied territory even though Israel annexed it (ICJ 2004, para. 78; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005, 303). In terms of citizenship, most Jerusalem Palestinians lack Israeli citizenship (Zemach Reference Zemach2020; Ramon and Ronen Reference Ramon and Ronen2017). Concomitantly, ever since 1967, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem have refused to participate in local elections despite their power to do so.Footnote 3 Over the years, their voter turnout has been around 1 percent, and there has never been a Palestinian city council member (Blake et al. Reference Blake, Bartels, Efron and Reiter2018). Notwithstanding, the Jerusalem Municipality functions as the only local government on the ground. The outcome of avoiding participation in municipal politics is that Palestinian communities in Jerusalem are left totally unrepresented at the local level, in particular in the land use planning commission, where expropriation powers lie (Rosen and Charney Reference Rosen and Charney2016).

The city was dramatically transformed shortly after the 1967 annexation, as the state expropriated large chunks of land in East Jerusalem for the purpose of establishing new Jewish neighborhoods (Holzman-Gazit Reference Holzman-Gazit2016; Cohen Reference Cohen2011) to forcefully “Judaize” the space in breach of international law (ICJ 2004, para. 120). Due to these expropriations being clearly intended for the sole benefit of the Jewish population and given that they were executed by the state, they are not the subject of this study and are presented only to provide proper background. Furthermore, I seek to focus on the development of Jerusalem decades after the annexation. Doing so enables me to discover the effect of the political setting on the practices of city officials even thirty and forty years after the annexation. In total, about 6,253 acres were expropriated by the state in East Jerusalem, mostly in the 1970s (Sandberg Reference Sandberg2010; Jerusalem Municipality: City Planning Division 1996; GIS analysis). These state expropriations amount to 36 percent of the annexed territory, leaving to Palestinian neighborhoods 64 percent of the annexed territory, or 36 percent of the entire city. Some of the expropriated land was uninhabited Palestinian land prior to its expropriation, some of it was cultivated by Palestinians, and some was vacant rural land, which Israeli law considers state property. No exact numbers are currently available (Sandberg Reference Sandberg2007, 97–98).

In Israel, expropriation decisions are often made even with respect to properties that are already owned by the state or other government agencies, so that the mere act of expropriation is not enough to determine that the land in question is privately owned. This occurs due to “releasing” land from one agency to another; clearing ownership rights in cases of competing claims; when there is uncertainty concerning property boundaries; and when state ownership is shared with private owners. In the context of the state’s 1970s expropriations, an additional motivator was the political urgency of developing the annexed areas as much and as fast as possible so as to “‘turn over a new leaf’ in the history of the title of the expropriated land” (Sandberg Reference Sandberg2004, 217).

It is difficult to determine whether the land expropriated in the 1970s was originally private or public, for two main reasons. Firstly, we cannot learn from actual compensation paid (even if this data was available) as it is reasonable to assume that many potential Palestinian claimants did not submit a claim for compensation, perceiving such claims as legitimizing the illegal annexation (cf. Atuahene Reference Atuahene2016b, 190).Footnote 4 Secondly, most of East Jerusalem’s land was not registered prior to 1967. In particular, no records are publicly available for the land expropriated in the 1970s. Some portions of these expropriated lands remained uninhabited or undeveloped decades later (e.g., Nuseiba v. Minister of Finance, 1994). As a result, it is possible to assume that some of the land that by the 1990s was categorized as “state land” was in fact formerly expropriated property of Palestinians. If discriminatory patterns with respect to the use of state land are found, that fact of former Palestinian ownership makes this discrimination even harsher.

Israel’s system of land records is based on a British Mandate procedure still in effect. This Torrens-type procedure, also referred to as “settlement of title,” is based on a comprehensive land survey of all claims to land in each and every locale, followed by a judicial determination of the governing property rights, the outcome of which process is conclusive title. The settlement of title thus combines both the process of land formalization and the substantive decision of to whom the land belongs (Kedar Reference Kedar2016, 880–81; Forman Reference Forman2002). The settlement procedures begun by British officials were continued by the State of Israel after it gained independence in 1948, so that today about 96 percent of the country is covered (Land Registry Annual Reports). Concomitantly, the Jordanians also continued with settlement of title processes in the areas that they governed, East Jerusalem included, until 1967.

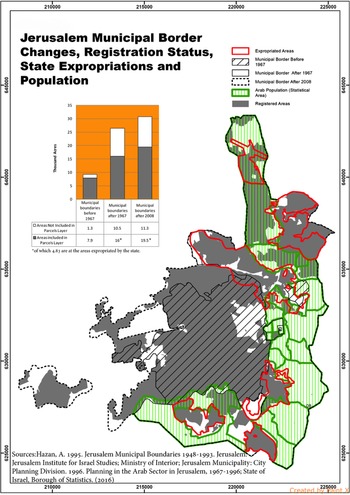

Starting in 1967, Israel suspended the settlement of title procedures in East Jerusalem as a matter of policy related to the prevailing political (cf. Cai, Murtazashvili, and Murtazashvili Reference Cai, Murtazashivili, Murtazashvili and Wang2020). Thus, and alongside other contexts of settler or colonizer societies, such as the case of the American Indians (Alston et al. Reference Alston, Crepelle, Law and Murtazashvili2021), it maintained disparate property institutions for the two groups, where those serving Palestinians were clearly weaker. Consequently, while 84 percent of West Jerusalem’s land, including the neighborhoods built on the 1970s expropriations, have undergone settlement of title or otherwise registered in the land registry,Footnote 5 only 27 percent of East Jerusalem (excluding the 1970s expropriations) is currently registered (17 percent) or under (de facto suspended) settlement of title proceedings (10 percent). I shall refer to these 27 percent as “registered” or “formalized properties” [Map 1].

The distinction between formalized and nonformalized properties in East Jerusalem itself can be regarded as-if randomly (Dunning Reference Dunning2012, 11). Firstly, the land settlement process that preceded 1967 was not organized in any particular way: The Jordanians had planned to complete the process for all lands under their control; it was only the sudden outbreak of the war that put an end thereto, leaving some properties settled, others in process, and still others completely nonformalized. Secondly, it is commonly asserted that there are no significant differences between formalized and nonformalized lands held by Palestinians owners, in terms of land transactions, land cover, and land prices (Nesher Reference Nesher2018). This can be explained by the great volume of properties that are not formalized, and by the fact that for the relevant buyers and sellers in the market—mostly Palestinians—there are other unofficial means to secure a transaction (e.g., the mukhtar system, see Mishal v. Camal, 2020; and compare with Hajj Reference Hajj2016 on the development of property records in a stateless setting of Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon).

The ethnoreligious residential separation between East and West Jerusalem, the result of historical and political circumstances,Footnote 6 has been maintained to date [Map 1]: Less than 1 percent of West Jerusalem’s population is Palestinian. Of Jerusalem’s Jewish population, 63 percent reside in West Jerusalem, while the rest inhabit the new neighborhoods erected on the 1970’ expropriated land in East Jerusalem (Jerusalem Statistical Book 2015). It is more accurate therefore to distinguish between the two subcities of Jerusalem: a Jewish subcity (West Jerusalem, plus Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem); and a Palestinian subcity (East Jerusalem, excluding the Jewish neighborhoods).

As evidenced from Jerusalem’s highly segregational composition, these two subcities are self-sustaining, i.e., one does not have to travel from Jewish to Palestinian Jerusalem in order to secure most services. This is especially true of Jewish Jerusalem (Baumann Reference Baumann2016; Raanan and Shoval Reference Raanan and Shoval2014). There are, however, many citywide roads (including the recently completed light rail) that bisect the city. In addition, regional and national roads run within the city’s boundaries. Other parts of the city that serve all populations include the Old City, two industrial areas, hospitals, government offices, the central business district, shopping malls, stadiums, and the zoo (Shtern Reference Shtern2016). When analyzing the functionality of public goods, we can distinguish between those that benefit Palestinian or Jewish neighborhoods, and goods that have citywide functions. Citywide goods are not necessarily planned for the equal benefit of the two communities. It is reasonable to assume that what may be viewed as being of neutral character is in fact predominantly aimed at serving the Jewish communities.

Map 1. Jerusalem municipal border changes, registration status, state expropriations, and population.

The two subcities are distinct in their religion and national-ethnic identities of their inhabitants, which is strongly associated with differences in voter turnout and the respective presence/absence of land registration. Many other differences between the two subcities are likely also related to ethnoreligious differences or to consequential differences in political power and security of title [Table A1]. For example, in 2010–2014, only 15 percent of building permit applications were submitted for properties in Palestinian Jerusalem (State Comptroller 2016, 1153). One of the purposes of this article is to elucidate the political implications of occupation and illegitimate government. It empirically tests how the political setting shapes day-to-day decisions, and ferrets out whether the veneer of legality hides an abuse of power.

The City of Jerusalem argues that its taking decisions follow planning needs and are not biased against Palestinian residents, contrary to Hypothesis 1. However, it does admit a worrisome gap in the supply of elementary schools and playgrounds between Jewish and Palestinians residents (e.g., Abu Labada v. Minister of Education, 2011). Corroboration thereof can be found in a recent study that showed that as of 2019, the per capita share of public buildings in Palestinian Jerusalem is half (4.4 sqm) that of Jewish Jerusalem (9.6 sqm) (Assaf-Shapira and Yaniv Reference Assaf-Shapira and Yaniv2020, 19). The city has argued that its failure to provide sufficient playgrounds in Palestinian neighborhoods is partly due to poor land registration and the “necessity” of expropriating land, which is fraught due to the difficulty in determining the owners’ identity and calculating the compensation costs where land records are lacking (TZAHOR v. Jerusalem Municipality, 2015). The city thus echoes the conventional wisdom, contradicting Hypothesis 2, that weak property rights (in this case, lack of land records) induce low levels of development and expropriation activity. This will be now tested.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Strategic Approach

In Israel, as in many other jurisdictions, taking powers are reserved for both local and central governments. This study analyzes local-level takings only.Footnote 7 In order to take private property for local uses, the local government must first enact a comprehensive plan or a zoning map (or amend an existing one) and designate land for public uses. In large cities such as Jerusalem, the local planning and building commission (i.e., zoning commission) is comprised of all members of the city council, headed by the mayor, so that there is a complete overlap between the planning body and the elected local government. Elections for mayor and city council, and consequently, a seat on the zoning commission, are held every five years.

Under the law, the zoning commission is responsible both for approving the designation of certain lots for public uses and for their ensuing taking. In practice, taking decisions are made by a subcommittee of the zoning commission headed by the mayor or his/her deputy. After a zoning map is amended to designate property for public use, the commission may publish a notice declaring its intent to take the designated property and demand immediate transfer of possession.Footnote 8

I used correlating methodology to identify for each taking instance the identity of the contributor (landowner) and the beneficiary (the city as a whole, or one of the communities: Palestinian, or Jewish) that the repurposed land would benefit. I also matched the results with information on the specific public use for which the land was expropriated, and studied the effects of land records on the taking practice.

The beneficiaries of a taking project are those communities whose living conditions are expected to improve consequent to the development. For instance, a new public school benefits its immediate surroundings (in terms, e.g., of quality of life and property values). Obviously, public uses such as landfills do not create positive externalities. Projects of this type are not included in the present study, as they were not found. In all of the cases wherein municipal taking was involved, the use thereof was for roads, open public spaces, and public buildings such as schools—uses that generally generate positive values (Bertram and Rehdanz Reference Bertram and Rehdanz2015; Mikelbank Reference Mikelbank2005). In a segregated city such as Jerusalem, each public good benefits either a Jewish or a Palestinian neighborhood, or citywide users (e.g., inter-neighborhood roads) and services meant to benefit unidentified residents, commuters, or tourists (main arteries, government offices, major parks, etc.).Footnote 9

Land ownership in Jerusalem can be public or private, or jointly shared by the state and private owners. Public ownership, referred to as “state land,” is comprised of land administered by the Israeli Land Authority (ILA), Custodian of Absentee Property (see Supplement for details), or municipal property. Private owners can be Palestinians or Jews. Religious institutions, such as the Islamic Waqf and churches also own property in Jerusalem. The former and latter were identified as Palestinian and Jewish owners, respectively.Footnote 10 Nonformalized land in Palestinian Jerusalem is referred to as Palestinian/state land, and given the identity of the potential claimants thereto.

Note that the city often expropriates state land that was already public, owned by the state or other government agencies. As further elaborated below, the decision process and the taking notices do not distinguish between the taking of private and public land.

Data

The primary data resource is a hand-coded dataset of all taking notices published in public records by the Mayor of Jerusalem on behalf of the local Zoning Commission. These records are known as “Official Records” or “Official Gazette” [Hebrew: yalkut ha-pirsumim], and are published on an ongoing basis by the Governmental Publisher. Taking is not complete if a notice has not been published in these records.

The research period includes all notices signed and published between January 1, 1990 and December 31, 2014. The notices were collected from the official records in two complementary ways. First, through an online search of a leading legal database, which contains all of the official records as.pdf files. In addition, a manual search through all hard-copy records was conducted (two independent research teams conducted each of these searches).

A taking notice includes, for each taking instance, the taking date, reference to the number of the relevant zoning amendment, and the specific public use for which the land was taken (i.e., roads, open public spaces, public buildings, or a combination of these uses).Footnote 11 In many cases, the public notice contains information about the location of the taken lots as identified by block and parcel numbers. In other cases where the land is not listed in the records, only block numbers are available or just a general description of the taking area bounded by longitude and latitude lines. In many of the cases in the past decade, the notices contain information about the size of the land taken. Due to lack of minimal data, I was unable to compile sufficient data for 3 percent of the takings out of the entire sample. In total, there were 3,448 taking instances, related to 369 development projects.

An additional primary resource for this study was the city archives, to which I was granted full access thanks to the support and cooperation of the City Hall.Footnote 12 My research assistant scanned all of the city’s hard-copy files for the research period: 422 files, including 2,348 documents. The taking procedure was not completed in all files, in which cases the data was not included in the study. In some cases, a single project was covered by several files. I conducted a matching process to identify whether all taking notices gathered from the Official Records were included in the city’s files. Indeed, in a few cases, there was an official taking notice, but the city’s file was missing.

For 312 (85 percent) of the development projects included in this study, the city’s taking file was available. Some files were lost due to bureaucratic disorganization. Most of the files contain photogrammetric maps of the taking area, as well as measurement charts of the taking size per lot taken (or per area defined by its location), compiled by a land surveyor. In many cases, the files contain information about the landowners. The files also contain the minutes of the decision to expropriate the land. In the vast majority of cases, the minutes are just standard format with no evidence of specific deliberation on the project at stake. I coded the place names appearing on the city file’s cover, as well as all other information from the taking process contained in the files.

As an additional data resource, I reviewed the zoning amendment documentation for each project, including the zoning map and the written explanation. The data is scanned and available on the city’s website, including through a GIS platform that presents the geocoded zoning maps.

I also conducted several meetings and open interviews with municipal officials.Footnote 13

I obtained additional data on land ownership as described below.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

Taking Activity Levels

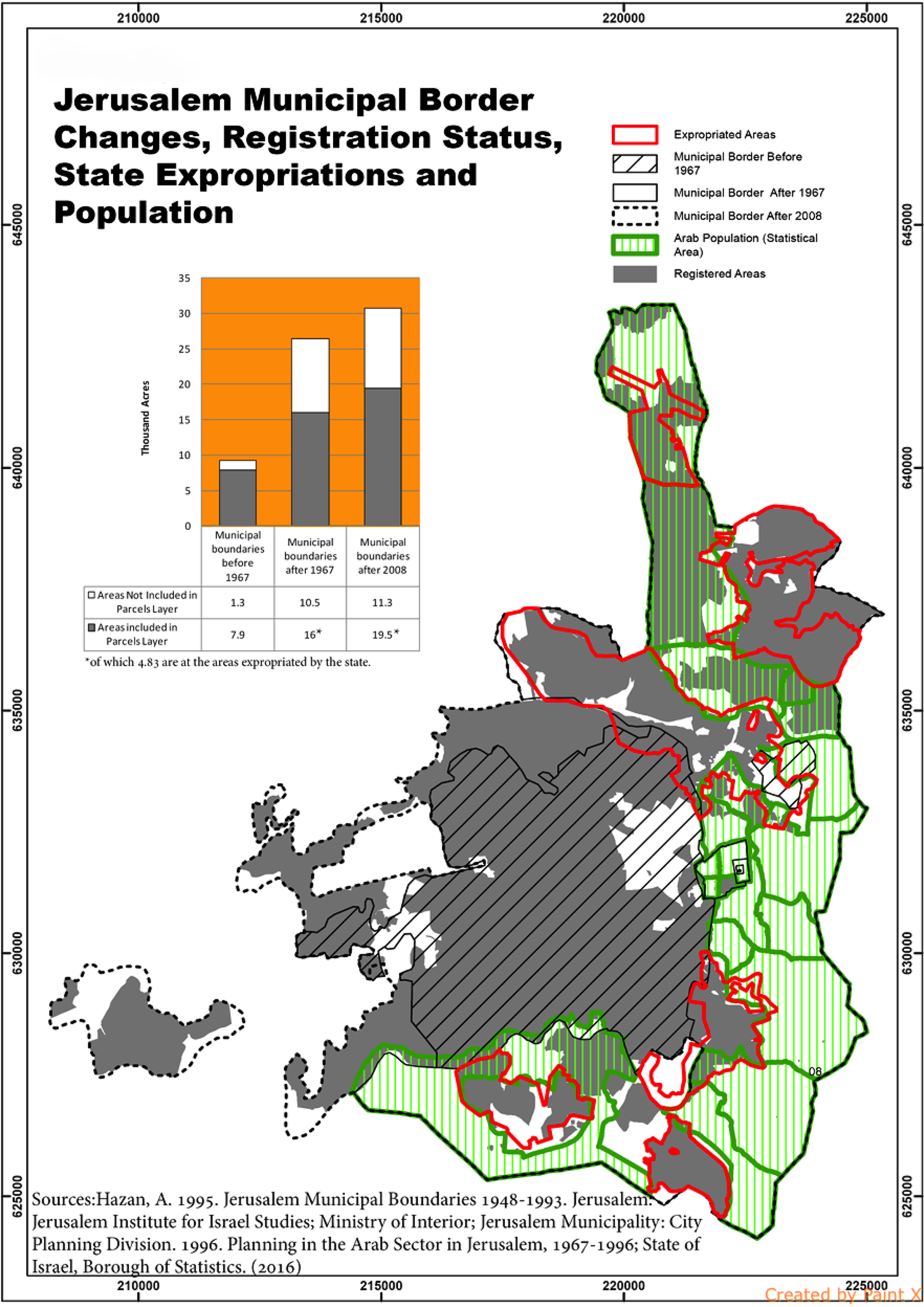

The number of projects varies year to year without any identifiable trend. The year 2014 witnessed a peak with 29 (8 percent) development projects. The lowest number of projects was three, in 2003. The annual average was fifteen. There is insignificant correlation between the number of projects undertaken and the amount of land taken each year (r = 0.38, p < 0.06) (Figure 1). In total, at the time of this study, 1,935 acres have been taken, amounting to 6.28 percent of Jerusalem’s size. This compares to 926 acres taken during the same period in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, and to a similar share of 7.2 percent of the city’s size. The average taking per development project in Jerusalem is 5.25 acres, compared to 2.06 acres in Tel Aviv (Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky Reference Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky2016), which can be explained by the existence of underdeveloped land reserves in Jerusalem.

FIGURE 1. Number and Size of Takings Projects, 1990–2014.

Beneficiaries

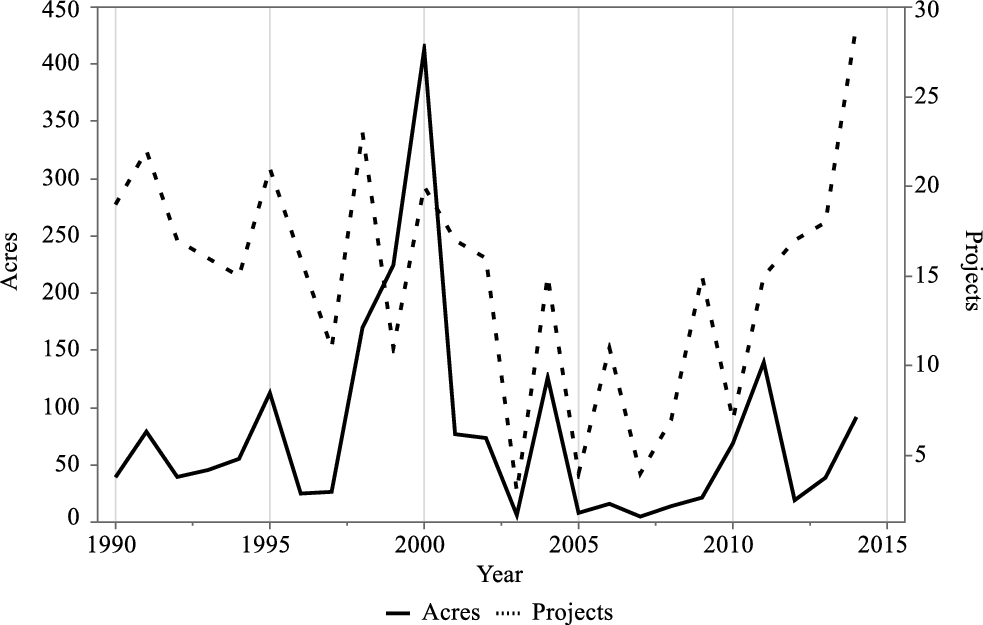

For each project, I analyzed location, designated purpose, and functionality as described in the zoning file. In addition, I referred to the place names appearing on the city file’s cover, as well as other information from the taking process (minutes, etc.). The type of beneficiary was determined accordingly. Figure 2 presents the distribution of land taken by type of beneficiaries: 1,088 acres (56 percent) were allocated to citywide purposes, 646 acres (33 percent) to Jewish neighborhoods, and the remaining 200 acres (10 percent) to Palestinians.

FIGURE 2. Land Taken by Beneficiaries.

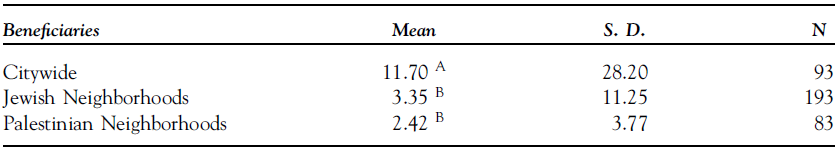

When inspecting the distribution of projects (not the amount of land taken), it appears that the Jewish population benefited from 52 percent of the development projects, while the rest were almost evenly distributed between citywide (25 percent) and Palestinian purposes (22 percent). Table 1 shows the correlation between project size and beneficiary type and can explain why, despite the similar shares of projects aimed to benefit citywide and Palestinian purposes, the distribution of land taken for the benefit of each of these groups is dramatically different: Citywide projects require much more land than neighborhood-level projects.

TABLE 1. Project Size (in Acres) by Beneficiaries

Levels not marked by the same letter differ significantly.

(Total α = 0.05)

The differences in the distribution of benefits between Jewish and Palestinian neighborhoods should be evaluated against differences between these communities in terms of overall neighborhood area and population. Both measures are about the same: 37 percent of Jerusalem’s population is Palestinian, and 36 percent of the city’s land lies in Palestinian Jerusalem. Based thereon, assuming that all else is equal, the proportional allocation of benefits between Jewish and Palestinian neighborhoods is 64–36 percent. The de facto allocation of land taken for Palestinian neighborhood uses (200 acres) is only 0.55 of what it should be (363 acres) relative to their size given the benefits enjoyed by the Jewish community. If, however, the citywide share (1,088 acres) is deducted, then the relative allocation of the rest becomes 542 acres to Jewish neighborhoods (64 percent), and 305 acres to Palestinian neighborhoods (36 percent). The actual distribution is, nonetheless, 76–24 percent (Odds Ratio = 1.82; 95 percent Confidence Interval 1.47–2.26; p < 0.001), meaning only 0.67 of what it should be relative to neighborhood size.

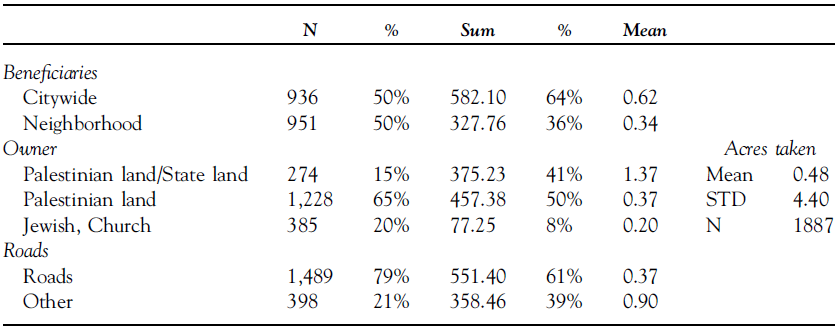

Owners

In order to determine the ownership of land prior to its taking, a two-stage procedure was employed. First, the ownership category was asserted based on the property’s geographical location (Jewish or Palestinian Jerusalem) and its surroundings, identified by GIS, and on its registration status as per the taking notice (where unregistered land in Palestinian Jerusalem would be initially considered Palestinian/state land). Several verification methods were then employed: If land records exist, the owner’s name clearly indicated whether s/he was Palestinian.

Out of 3,138 observations, 2,805 lots were identified by block and parcel, and therefore potentially traceable in the registry.Footnote 14 For a sample of 877 observations out of this subset (31 percent), a request for official land records was submitted.Footnote 15 In 397 cases, land records were unavailable; hence, the lots had been surveyed for tax purposes, but not registered. In 497 cases, land records were obtained. The success rate for a record request was therefore 57 percent.

The sampling method was randomized as follows: Data was requested for every ten consecutive parcels in the registry that contained one to two taken properties. If more than two parcels were taken in a given ten-parcel set, information for two randomly selected parcels was requested, or for more if no information was available for the first two. Given the city’s segregational composition and jurisdiction, it is fair to assume that properties adjacent in parcel listings are neighboring and owned by the same owner type (Grigoryeva and Ruef Reference Grigoryeva and Ruef2015; Sandberg Reference Sandberg2000).Footnote 16 Therefore, where records were obtained, adjacent properties (identified by sequential parcel numbers) were assigned the same owner class. However, if there were reason to doubt that the results would be systematic—i.e., when each of the two sampled records per ten-parcel set referred to a different type of owner, or when at least one record indicated private Jewish ownership in a Palestinian neighborhood or vice versa (highly rare)—land records were requested for the entire set of adjacent parcels.

Next, state ownership was verified using the ILA online database.Footnote 17 Where land records were not obtained, I relied for verification on information found in the city’s taking files and in the zoning records. In many cases, the city’s files contained a note about the funding source for the compensation; public land was usually noted, as this status had bearing on the compensation component. In addition, as required by zoning regulation, in many of the small-scale development projects, the developers had to be the owners or leaseholders, and this information was available in the files. The land’s characteristics—built, vacant, or agricultural—as described on the survey maps in the files, and its current status based on GIS analysis, were also considered. In cases of unregistered land in Palestinian Jerusalem, if there was no clear data about the owner’s identity, it was regarded as Palestinian/state land. For this group, I estimate that a share of 73 percent should be reasonably attributed to Palestinian owners.Footnote 18

Figure 3 shows the share of land taken by owner type. As can be seen, takings from state land represent the dominant group (52 percent), followed by Palestinian owners (24 percent), and a mix of these two categories (19 percent). Representing this category as per relative shares (73 percent Palestinian, 27 percent state) would mean that effectively, state land in the sample is 57 percent of the taken land, while Palestinian Land includes 38 percent of the taken land. Only 4 percent of the land in the taking sample was taken from private Jewish owners and churches (2.8 percent and 1.2 percent, respectively). A small fraction (1 percent) of land was taken from other mixes of owners, and was therefore excluded.

FIGURE 3. Landowners in the Takings Sample v. in Jerusalem.

An important consideration is the baseline: how land ownership is distributed among the various owner types at city level (not in the expropriation sample). There are no clear data thereabout. According to expert estimates, churches own about 1,236 acres in post-1967 Jerusalem (Margalit Reference Margalit2012). Another 6,253 acres of Jewish Jerusalem are categorized as “state land” following expropriation in the 1970s, while another 4,349 acres are mostly vacant land west of the city that was incorporated to the city limits in 1993 (Hazan Reference Hazan1995; Jerusalem Statistical Book 2015, Table I/1). Regarding the rest, of 7,954 acres in Jewish Jerusalem, based on previous estimates of the small share of private Jewish ownership in Israel (Sandberg Reference Sandberg2007; Kark Reference Kark, Troen and Lucas1995), I attributed 10 percent to private Jewish ownership and the rest to state ownership. However, enlarging the share to 20 percent or even 30 percent, for instance, would not have changed dramatically the overall map of ownership, allowing 5–8 percent of private Jewish ownership. In Palestinian Jerusalem, 2,991 acres were settled or under settlement of title proceedings at the time of annexation. I estimate that 90 percent of these properties are privately owned by Palestinians, and the rest are state land (including local roads). The rest of this part of the city, 8,029 acres, I regard as Palestinian/state land.Footnote 19

I therefore cautiously estimate that state land represents 59 percent of Jerusalem’s land, which are respectively 90 percent of Jewish Jerusalem and 3 percent of Palestinian Jerusalem; Jewish and church ownership is 7 percent (3 percent and 4 percent respectively), or 10 percent of Jewish Jerusalem. The Palestinian private ownership rate is 9 percent of the entire city, or 24 percent of Palestinian Jerusalem. Palestinian/state land represents 26 percent of Jerusalem, or 73 percent of Palestinian Jerusalem.

Palestinian land is clearly overrepresented in the taking sample, i.e., land is taken from Palestinian owners 2.7 times more than their share in the general population of landowners. Jewish land is represented in the sample at the exact same rate as in the general population.Footnote 20 However, the church category is underrepresented: 4 percent ownership versus 1 percent taking rate; the state land and Palestinian/state land categories are also slightly underrepresented in the taking sample.Footnote 21

Owners v. Beneficiaries

The next step is to correlate beneficiaries and owners. Figure 4 shows the beneficiaries of the taken land by owner type. A few observations can be made here. Firstly, state land is distributed almost exclusively and nearly equally to citywide and Jewish neighborhood uses (49 percent and 48 percent, respectively). State/Palestinian land is also used exclusively for citywide (75 percent) and Jewish neighborhood (25 percent) uses.Footnote 22 Recall that 27 percent of this category can be attributed to state land and the rest to Palestinian land, although none of the taken land in this category was redistributed for the benefit of Palestinian neighborhoods. The Palestinian land category is mostly used for citywide uses (61 percent), but also for Palestinian uses (38 percent). Jewish land, however, is mostly distributed to Jewish neighborhood uses (71 percent), with the rest going to citywide uses.

FIGURE 4. Distribution of Beneficiaries by Owners.

Specific Public Uses

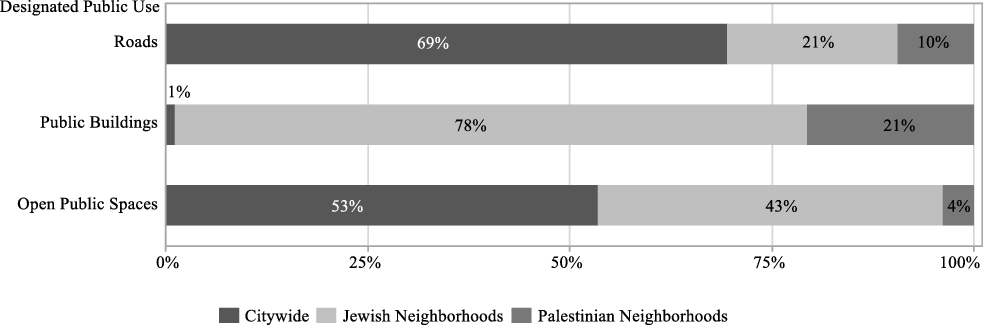

For each observation, the public use for which the land was taken was identified in the taking notice or the city’s file.Footnote 23 I found that the main public use for which land is taken in Jerusalem is roads: 69 percent of all land taken over the years (for similar results in Tel Aviv, see Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky Reference Levine-Schnur and Parchomovsky2016), while the rest is split evenly between public buildings and open public spaces.

Notably, 85 percent of the land taken for citywide uses is for roads (the rest is divided 15 percent for open public spaces and 0.003 percent for public buildings). When comparing designated uses between Jewish and Palestinian neighborhoods, the results differ dramatically: For Palestinian neighborhoods, only 37 percent of the land is allocated to uses other than roads: 6 percent for open public spaces and 31 percent for public buildings; for Jewish neighborhoods, the respective shares are 43 percent for roads, 37 percent of open public spaces, and 20 percent for public buildings. Figures 5 and 6 show the relationship between uses and beneficiaries by beneficiary type in either direction, respectively.

FIGURE 5. Distribution of Public Uses by Beneficiaries (Land Taken).

FIGURE 6. Beneficiaries of Land Taken by Taking Uses (Land Taken).

Keeping in mind the groups’ relative sizes (Palestinian Jerusalem is 0.56 of Jewish Jerusalem in terms of size and population), it is evident that Palestinian neighborhoods are underrepresented in land designated for public buildings and open public spaces, but fairly represented in land designated for roads (assuming equal needs and past distributions).

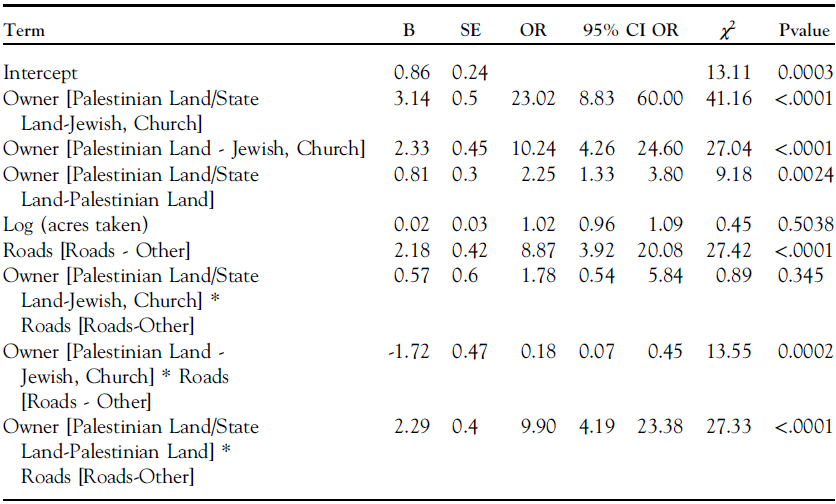

Modeling the Effect of Owners’ Identity and Weak Property Rights

To examine the effect of owners’ identity as well as that of weak property rights on the expropriation risk, I estimate a binary logistic regression wherein the dependent variable is Beneficiaries, i.e., who benefits from the land taken—the community or the city at large. Because Jewish land is hardly ever taken for Palestinian neighborhood uses and vice versa, and hence intersectionality at the neighborhood level is rare, the model can be best characterized as categorical: whether the beneficiary is the owner’s community (Neighborhood) or the general public (Citywide). The independent variables are Owner Type (state land is excluded), Taking Size, and the dummy Roads (equals 1 for takings whose sole use is roads, and 0 otherwise). Interactions between the variables are also shown.Footnote 24 The correlation between the probability of contribution to citywide uses, owner type, and specific public use can thus be estimated.

The model enables comparing the propensity of land to be taken from an owner for noncommunity ends, for three types of owners: Jews, formalized Palestinian, and nonformalized Palestinian owners. It also enables observing whether there are differences between the groups if the land taken for noncommunity uses is for citywide roads or other public uses.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the breakdown of the takings across beneficiaries, owners, and purposes. Table 3 depicts the logistic model.

TABLE 2. Descriptive Statistics

TABLE 3. Regression Analysis for Beneficiaries (Citywide v. Neighborhood) (State Land Excluded)

For log odds of citywide/Neighborhood. McFadden’s R2=0.114, N=1,887

The model reveals that there is a significant land records and landowners’ effect. Compared to Jewish land, for formalized Palestinian land the odds ratios for citywide taking ranges between 10.24 and 16.29 for nonroads and roads, respectively. For nonformalized land (that is mostly claimed by Palestinians) the odds ratio for citywide takings is 23.02 and there is no significant difference between the specific public purposes (roads and nonroads). Comparing formalized Palestinian land and nonformalized land the odds ratios for citywide takings are 2.25 for nonroads purposes and 19.94 for roads (all findings are significant at p < 0.005).

Thus, the taking of nonformalized land for noncommunity purposes is always higher when compared to formalized land. These findings are consistent across purpose categories. The model also indicates the significance difference between Jewish and Palestinian Land (formalized and nonformalized). Land owned by non-Jews has a higher propensity to be taken for city wide purposes by ten to twenty-three times.

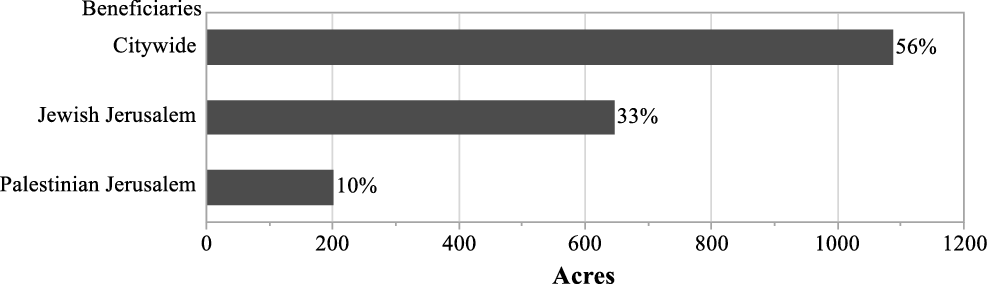

DISCUSSION

The data reveals clear differences in taking patterns between Jews and Palestinians in Jerusalem. In this city, Palestinians bear most of the private costs of supplying public goods, while benefiting from less than their relative share in terms of the size of their community or their forced contribution of land. Considering their relative share in nonformalized land, Palestinians contributed effectively 38 percent of the land taken by the Jerusalem Municipality in 1990–2014, while their neighborhoods benefited at the local-neighborhood level from only 10 percent of that land. For Jewish owners, the opposite ratio applies: 4 percent and 33 percent, respectively. The majority of the land expropriated from Palestinians was used for citywide purposes, and the rest for Palestinian neighborhood ones. Land taken from Jews and churches, however, was used almost only for Jewish neighborhood purposes. State land was used almost only for Jewish and citywide purposes.

Thus, despite the fact that over the course of twenty-five years, Palestinians contributed 36 percent of the land used for citywide goods, they benefited at neighborhood level from only 2 percent of the land taken from the state to be redistributed in the planning process. For Jews, again, the opposite ratio applies: 3 percent and 48 percent, respectively. Furthermore, most of the land designated for public buildings (schools, kindergartens, daycares, etc.) and spaces (parks) went to Jewish neighborhoods, whilst land taken for Palestinian neighborhoods was used mostly for roads. Thus, the city took land from Palestinian owners for citywide services but failed to supply Palestinian neighborhoods with enough open public spaces and public buildings compared to Jewish neighborhoods, despite their greater land contribution.

The large share of state land takings is not surprising and follows the relatively large share of state land in the city’s ownership map. Again, the redistribution of this public property is problematic. The data show worrisome disparities in the reallocation of state land between Jewish and Palestinian communities. Of the 1,105 acres (57 percent of the entire sample) taken from state or other public authorities, including the state’s relative share in Palestinian/state land, 50 percent of the land was repurposed for citywide uses and 47 percent for Jewish communities. Palestinian neighborhoods, however, benefitted from only twenty acres of state land (less than 2 percent of this category). At the same time, they effectively contributed 484 acres to citywide uses—66 percent of the land taken from Palestinian owners (including their relative share in Palestinian/state land).

The very small share of takings from non-Palestinian private owners—only 4 percent of the entire sample (seventy-seven acres) was taken from Jews and churches—can be partially explained by the low rates of private Jewish ownership in Jerusalem. Moreover, Jewish owners sometimes secure agreements with the local government where property is voluntarily transferred to the government’s hands in return for density bonuses or other benefits. Previous studies on these agreements in Jerusalem did not report any case where a Palestinian developer was party to such an agreement (Alfasi and Ganan Reference Alfasi and Ganan2015). Another mechanism is reparceling or readjustment of land, which allows identifying portions of a newly demarcated parcel as designated for public uses without following full expropriation procedures (Gielen and Mualam Reference Gielen and Mualam2019). In such cases, the designated land is used for Jewish community uses (based on interviews with city officials).

Another possible explanation for the scarcity of takings from Jewish owners might be that Jewish-owned areas of the city are more developed. The land cover may set limitations on the possibility to take land without having to evacuate people. The taking of vacant land might be cheaper and less politically sensitive, and therefore more common.Footnote 25 For example, a study in New York City found that half of the total condemnation settlements between 1990 and 2002 were of vacant land (Chang Reference Chang2010); and a study in Philadelphia reported that 92 percent of the lots taken between 1992 and 2007 were vacant (Becher Reference Becher2014). However, our GIS analysis shows that the built/nonbuilt ratios in each of the subcities are almost identical: 46 percent of Palestinian Jerusalem and 45 percent of Jewish Jerusalem are not-built areas.

The overrepresentation of takings from Palestinians owners can also be associated with possible cost differences compared to Jewish land: if the government responds to direct budgetary considerations when it decides on expropriation (Blume, Rubinfeld, and Shapiro Reference Blume, Rubinfeld and Shapiro1984), it would opt to take properties of lesser value, the compensation for which is concomitantly lower (Chang Reference Chang2010; Innes Reference Innes1997). A weaker version of this assertion, in line with recent studies (Schäfer and Singh Reference Schäfer and Singh2018; Chang Reference Chang2009; Levinson Reference Levinson2000), would be that the government responds to budgetary considerations, but not exclusively: other, political or purely professional planning considerations are also at play.

Indeed, residential land values in Palestinian neighborhoods are 55 percent of the equivalent values in Jewish neighborhoods.Footnote 26 This gap has further implications on the taking costs. The gross property tax charges per acre in Palestinian parts of the city are 37 percent of their equivalent in Jewish neighborhoods [Table A1]. It could be argued that the low level of amenities provided by the government affects the relatively low land prices, and that in return pushes the government to further take from Palestinians for citywide uses. Unfortunately, specific data about land values of the properties taken is unavailable. The redistributive effect I observe is therefore not only with regard to transfers from Palestinians to Jews, it is also potentially with regard to transfers from the poor to the rich. As already hinted and as previously observed in the literature, these two stories are not independent (Somin Reference Somin2015; Becher Reference Becher2014; Chen and Yeh Reference Chen and Yeh2012; Carpenter and Ross Reference Carpenter and Ross2009) and this is yet another case for the effects of intersectionality and the need to provide public policy solutions to them (Hankivsky and Cormier Reference Hankivsky and Cormier2011; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1988).

The differences between Jews and Palestinians are especially troubling when comparing the specific public uses between the two communities. Palestinian neighborhoods enjoy far fewer acres of open public spaces and public buildings than Jewish neighborhoods. The fallout of this practice is that Palestinian neighborhoods suffer from critical gaps in classrooms, and have practically no playgrounds in some cases, among other gaps in the supply of public services (Assaf-Shapira and Yaniv Reference Assaf-Shapira and Yaniv2020; Kashti and Hasson Reference Kashti and Hasson2016; Jerusalem City Engineer 2004). The long-term consequences for mobility and prosperity for the next generations are troubling.

Given the abundant evidence that Palestinian Jerusalem received short shrift in government direct expenditures (e.g., State Comptroller 2019, 372), the findings corroborate the assertion that as eminent domain is a kind of government expenditure, it would track the same distributional patterns as direct spending.

The ultimate question is why the city does not designate either state or private land to Palestinian uses, despite their desperate need for public goods other than roads. Obviously, this is not due to land unavailability. The land taken from Palestinian owners is more than three times the land designated to serve their community’s needs. There may be geographic or topographic or other independent reasons that affect Palestinians more than others, but this seems unlikely. The data suggest that even with respect to land taken from Palestinians the city prioritizes citywide uses over local Palestinian ones. One explanation for this outcome could be that at least in some of the cases the city only executes development policies directed and funded by higher levels of government, or other external funding sources, thus distorting its decision-making process (Fischel Reference Fischel2004). If true, however, this only lends further support to the hypothesis that the distribution of burdens and benefits in the taking context is correlated with political power. In still other cases, the city expropriates in response to a bottom-up request of landowners seeking development. Such owners are able to negotiate the terms and location of the taking with government officials. Here again, the Palestinian voting boycott is costly, as it leaves them with no strings to pull in City Hall.

With respect to Hypothesis 1, that weak communities will bear a disproportional burden to supply public goods, the regression analysis shows that the odds ratios that Palestinian and Palestinian/state land in particular would be expropriated for citywide rather than local neighborhood uses are ten to twenty-three times significantly higher than those of Jewish land are. With respect to Hypothesis 2, that weak property rights endanger greater government’s predation, the study finds that poor land records in Palestinian Jerusalem not only do not stop the city from taking such land, but also encourage it to target nonformalized land for noncommunity ends rather than for local Palestinian needs. Nonformalized Palestinian land is used more than any other category for noncommunity needs, roads or elsewise. Thus, unregistered land is not used for Palestinian purposes despite the high rate of private Palestinian rights that should be associated with it. Rather, it is regarded as the most available source for land needed for citywide uses.

Lack of formal ownership may therefore be correlated with greater risk of unfair redistributive expropriation, in line with Behrer et al.’s (Reference Behrer2021) assertion and the intuition of land owners as reported elsewhere (Perego Reference Perego2019; Collin et al. Reference Collin, Dercon, Lombardini, Sandefur and Zeitlin2012). The question is why. One reason could be that nonformalized Palestinian land is even cheaper than formalized Palestinian land. As mentioned above, a common understanding of government officials is that there are no significant differences in the land cover and land values between formalized and nonformalized Palestinian properties. However, for the government as a compulsive buyer of property through the mechanism of expropriation, nonformalized land may be cheaper as unformal owners may lack the political clout to demand compensation. In Vahabi (Reference Vahabi2016) terms, the “booty cost” of expropriating these assets is lower than their economic or market value, making them more attractive to the government. Furthermore, it seems that there are also nonbudgetary reasons that can explain the expropriation patterns arising from the present findings. Officials can defend (even to themselves) the taking of nonformalized land more easily as harming nobody, and therefore not subject to potential legitimate opposition in the decision making and consecutive judicial process or in public opinion. In other words, the government acts opportunistically when it opts to take the more weakly protected property.

Holland (Reference Holland2019) found that stronger property protections in terms of popular perception, values of compensation, and availability of judicial review, encourage opportunistic behavior on part of the people. Here, I studied the effect of another property protection, one that is more commonly referred to in the literature on political economy of property rights, the availability of formal records, on encouraging opportunistic behavior on part of the government. I find a correlative relationship converse to that identified by Holland: weaker property protections encourage opportunistic decision behavior on part of the government. However, there is an important difference between the property protections tested in this study. I further contend that unlike compensation rules that provide high levels of compensation for subjective values and unlike appeal norms that allow appellants to stall projects until they are heard, well-defined property rights—that offer by definition stronger protection of property rights—will not encourage opportunistic behavior on part of owners. Put differently, while broad protections against expropriation (e.g., subjective compensation) might indeed stand against public works, clear and well-defined property rights stand against the state’s aggressive or opportunistic behavior, a restriction that would better be in place if weak protections against expropriation exist. This is especially prevalent when property records are not uniformly available, due to the voluntary nature of land recording or, as in this case, the government’s decision not to provide this public good of land registration to the specific group of minority owners. The conclusion is that strong property rights stall the government. Whether this is a good or bad thing depends on the availability of similar property protections for all potentially effected landowners; and on the availability of a system to assure a fair redistribution of the redevelopment gains.

To conclude, the taking of unformalized properties of oppressed minorities is subject to the least rigid political and budgetary incentives to avoid excessive use of the eminent domain power. Existing mechanisms designed to prevent unfair abuse of the expropriation power against weak political communities and unformalized owners are therefore inadequate. The final question is whether this is intentional or the outcome of “an incidental, and sometimes unavoidable, side-effect of government action” (Kaplow Reference Kaplow1986, 519). If it is intentional, then the fundamental distinction that is expected to be between taxation and expropriation, where the former is supposed to be intended for redistribution while the latter should not, does not stand. Could it be that the local government simply conceals its unfair but deliberate redistribution policies under the guise of legitimate expropriation proceedings?

When I presented the preliminary findings of the study to local officials from the City of Jerusalem, they abruptly denied such an assertion, supporting their actions on pure planning considerations. Bringing aerial photos to the room, they confronted me by asking, “How would you plan the road differently? The roads are where they are because there are no alternatives,” they forcefully argued. Following the meeting, they emailed me, claiming that in East Jerusalem they cannot undertake readjustment plans as they do in West Jerusalem, for reasons that they were unwilling to provide. In addition, they argued, in West Jerusalem they lease large portions of land for long periods from the ILA, an option that is unavailable in East Jerusalem, probably due to the unavailability of state land. However, the data shows that the city expropriates large shares of land from the ILA and does not lease them, even if no compensation is paid for the taking.Footnote 27 This disavowal narrative is in line with the official minutes and decisions of the municipal planning and expropriation processes, which I reviewed, that do not reflect any intentional harm to the Palestinian community.

Prior studies have shown that Israeli officials tend to justify their discriminatory land policies as innocent and necessary application of the law. For instance, according to Braverman (Reference Braverman2007, 335), Israeli officials consider the widespread phenomenon of illegal constructions in Palestinian Jerusalem the result of an egalitarian and professional application of planning laws. Relatedly, Kedar et al. (Reference Kedar, Amara and Yiftachel2018, 40-41) observed that Israel presents its dispossession of Bedouin land rights in the Southern parts of Israel, as the inevitable result of the continued enforcement of land laws that pre-dated Israeli statehood, despite that in fact it introduced significant changes to those laws through their radical reinterpretation. With respect to our current case, is hard to tell whether the officials in charge are just wise to argue (and present in their minutes) that they act in accordance with the law although this is just to conceal their true intentions, or are they truly oblivious to the aggregate dispossessive nature of their actions. If the latter is the case, then it may be an example of direct discrimination not involving an intention to disadvantage anyone on account of group membership or even knowledge thereof (Lippert-Rasmussen Reference Lippert-Rasmussen2014, 59–60). Importantly, however, this case demonstrates the weakness of any claim that hinges on proving intention to dehumanize or dispossess as a precondition to justify critical assessment of governmental practices. It really should not matter.

From a legal perspective, proving discriminatory intent is not a prerequisite for discrimination. Outcomes-based inequality is also recognized by the law. However, a one-by-one judicial review of taking decisions and individual compensation claims does not give courts the opportunity to address the dispossessory and discriminatory outcomes of expropriation practices. Absent actual representation at the decision-making level, and when no judicial intervention is practically possible, discriminatory practices spread and prevail. To start addressing this problem, local government should be held accountable to its actions by requiring it to provide information about the burdened and beneficiaries of each and every one of its decisions, and to conduct a community-based impact survey, including alternative planning options, before approving land takings. Further research is needed to better offer working models but clearly the current practices cannot be justified any longer.