Impact statement

This qualitative study aims to shed light on the experiences, daily problems and challenges young refugees, particularly ones from Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan face while living in the Netherlands, with the view of developing a suitable adaptation of Problem Management Plus (PM+) to address posttraumatic stress. Young refugees may be at risk for common mental disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, they experience several barriers and challenges reaching mental health services available in the Netherlands. By adapting an effective scalable intervention PM+ for young refugees from Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan in the Netherlands, this study aimed to develop a potentially acceptable and safe treatment strategy, contextually adapted for use in youth refugee care. This study also contributes significantly by introducing a newly developed, brief module that can be delivered through task-sharing and designed to address the processing of emotions associated with memories of negative or traumatic past experiences and reduce symptoms of PTSD. This module can be used in future randomized controlled trials among refugee youth exposed to traumatic experiences. Given the prevalence rates of PTSD among young refugees, integrating a module specifically targeting traumatic experiences into a scalable intervention like PM+ holds substantial promise. PM+ with the emotional processing module, adapted for use among young refugees, has the potential to yield improved outcomes in terms of reducing PTSD symptoms and related mental health problems among young refugees.

Introduction

Every year, millions of individuals are displaced globally due to wars, conflicts or various atrocities. The experience of such life-altering events during adolescence or young adulthood profoundly impacts psychological well-being. While prevalence rates differ across studies, most research demonstrates elevated rates of mental health problems among young refugees (Fazel, Reference Fazel2018; Kien et al., Reference Kien, Sommer, Faustmann, Gibson, Schneider, Krczal, Jank, Klerings, Szelag, Kerschner, Brattström and Gartlehner2019; Nesterko et al., Reference Nesterko, Jäckle, Friedrich, Holzapfel and Glaesmer2019). Given the heightened distress levels and the critical nature of formative years, prioritizing mental health interventions for young refugees is essential (Kien et al., Reference Kien, Sommer, Faustmann, Gibson, Schneider, Krczal, Jank, Klerings, Szelag, Kerschner, Brattström and Gartlehner2019). Furthermore, research also underlines the profound impact of distress related to the ongoing stressors in the host country (Miller and Rasmussen, Reference Miller and Rasmussen2017; Dangmann et al., Reference Dangmann, Solberg and Andersen2021). Understanding these daily stressors, alongside the potentially traumatic experiences, is crucial for developing psychological interventions tailored to address common mental health problems.

Refugees face barriers to accessing psychological interventions even in host countries with established mental health services (Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Acarturk, Bird, Bryant, Burchert, Carswell, de Jong, Dinesen, Dawson, El Chammay, van Ittersum, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Miller, Morina, Park, Roberts, van Son, Sondorp, Pfaltz, Ruttenberg, Schick, Schnyder, van Ommeren, Ventevogel, Weissbecker, Weitz, Wiedemann, Whitney and Cuijpers2017). A systematic review revealed that despite asylum seekers and refugees in Europe utilizing physical and emergency care at hospitals more frequently than the host population, they underutilize mental health services (Satinsky et al., Reference Satinsky, Fuhr, Woodward, Sondorp and Roberts2019). In a recent study examining the responsiveness of health systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East, researchers found that in European countries, the most important challenges hindering mental health service utilization included prolonged waiting periods and language-related barriers (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Fuhr, Barry, Balabanova, Sondorp, Dieleman, Pratley, Schoenberger, McKee, Ilkkursun, Acarturk, Burchert, Knaevelsrud, Brown, Steen, Spaaij, Morina, de Graaff, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Roberts2023). These challenges were compounded by additional issues concerning stigma and lack of mental health awareness (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Fuhr, Barry, Balabanova, Sondorp, Dieleman, Pratley, Schoenberger, McKee, Ilkkursun, Acarturk, Burchert, Knaevelsrud, Brown, Steen, Spaaij, Morina, de Graaff, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Roberts2023). Similarly, refugee youth who are resettled in Europe access mental health services less frequently than their peers in the host country, as demonstrated in studies conducted in Denmark (Barghadouch et al., Reference Barghadouch, Kristiansen, Jervelund, Hjern, Montgomery and Norredam2016) and the Netherlands (Bean et al., Reference Bean, Eurelings-Bontekoe, Mooijaart and Spinhoven2006).

The utilization of scalable psychological interventions, which are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as brief transdiagnostic interventions that aim to reach more people at lower costs (World Health Organization, 2017; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Harper-Sehadeh, Carswell, van’t Hof, Hall, Malik, Au and van Ommeren2018) can be a solution to improve access to mental health care. The necessity for scalable interventions emerged due to the inadequacies of mental health systems in conflict-affected settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Pinninti, Irfan, Gorczynski, Rathod, Gega and Naeem2017). A task-shifting strategy, in which the intervention is carried out by trained, nonspecialized people often from the same cultural backgrounds as the people who need these interventions, is often used. In the context of refugees having difficulties in accessing mainstream mental health services, scalable interventions have been beneficial for refugee populations in both LMICs and high-income countries that may have insufficient mental health specialists fluent in the refugees’ languages, or where refugees do not utilize services due to mental health stigma (Bryant, Reference Bryant2023; Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Fuhr, Barry, Balabanova, Sondorp, Dieleman, Pratley, Schoenberger, McKee, Ilkkursun, Acarturk, Burchert, Knaevelsrud, Brown, Steen, Spaaij, Morina, de Graaff, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Roberts2023).

One scalable intervention with strong evidence of its effectiveness is Problem Management Plus (PM+; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015; World Health Organization, 2017). PM+ has different modalities including an individual version (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015; World Health Organization, 2016), a group version (World Health Organization, 2020), a digital version (step-by-step; Carswell et al., Reference Carswell, Harper-Shehadeh, Watts, Van’t Hof, Abi Ramia, Heim, Wenger and van Ommeren2018) and a version that can be used with young children between 10 and 14 years old (Early Adolescents Skills for Emotions [EASE]; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Watts, Carswell, Shehadeh, Jordans, Bryant, Miller, Malik, Brown, Servili and van Ommeren2019). A recent meta-analysis that included 23 studies with individual PM+ or the digital version, step-by-step, reported a small to moderate effect on distress indicators such as general distress, anxiety, depression and PTSD symptom outcomes (Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Thomas, Lindner and Lieb2023). While initially developed for LMICs, recent research has shown that PM+ can also be effective in high-income settings in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety, PTSD symptoms and self-identified problems (e.g., the main unique problems participants report, such as problems with work or study; de Graaff et al., Reference de Graaff, Cuijpers, Twisk, Kieft, Hunaidy, Elsawy, Gorgis, Bouman, Lommen, Acarturk, Bryant, Burchert, Dawson, Fuhr, Hansen, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Morina, Moergeli, Park, Roberts, Ventevogel, Wiedemann, Woodward and Sijbrandij2023). However, no study to date focused on its feasibility for older adolescents (16–18) and young adults (18–25) specifically.

PM+ is considered a transdiagnostic intervention, aiming to reduce symptoms of various common mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety and PTSD. Indeed, PM+ has been found to reduce symptoms of PTSD such as re-experiencing and avoidance (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Koyiet, Rahman, Schafer, Hamdani, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij and Bryant2022). Although PM+ does not include trauma-focused strategies, the strategies taught in the PM+ program may facilitate emotional processing (EP) which could potentially contribute to reductions in PTSD symptoms (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Koyiet, Rahman, Schafer, Hamdani, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij and Bryant2022). Even though some studies found improvement in PTSD symptoms (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016; de Graaff et al., Reference de Graaff, Cuijpers, Twisk, Kieft, Hunaidy, Elsawy, Gorgis, Bouman, Lommen, Acarturk, Bryant, Burchert, Dawson, Fuhr, Hansen, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Morina, Moergeli, Park, Roberts, Ventevogel, Wiedemann, Woodward and Sijbrandij2023), other trials encompassing trauma-exposed populations found PM+ did not reduce PTSD symptoms (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, van’t Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bawaneh, Awwad, Al-Hayek, Giardinelli, Whitney, Jordans, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Ventevogel, Dawson and Akhtar2022). This may be explained by the lack of trauma-focused strategies in PM+ (e.g., exposure to traumatic memories), which is recommended for individuals with PTSD symptoms (ISTSS GC, 2018). Given the high prevalence rates of PTSD symptoms or experiences that might lead to PTSD among young refugees (Björkenstam et al., Reference Björkenstam, Helgesson, Norredam, Sijbrandij, de Montgomery and Mittendorfer-Rutz2020), integrating a scalable EP component into the PM+ intervention is an important topic to investigate.

Scalable interventions are easily adaptable across different cultures and contexts (Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Harper-Sehadeh, Carswell, van’t Hof, Hall, Malik, Au and van Ommeren2018). Research on the effectiveness of culturally adapted interventions has several methodological limitations (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Gega, Degnan, Pikard, Khan, Husain, Munshi and Naeem2018). It has been found, for example, that active control arms or non-adapted versions of the same intervention are often absent (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Gega, Degnan, Pikard, Khan, Husain, Munshi and Naeem2018). Despite these limitations, there is evidence that adapted interventions have larger effect sizes (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014) and to ensure the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of the interventions, carrying out cultural adaptations while maintaining the fidelity and core components of the intervention is recommended (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; Fendt-Newlin et al., Reference Fendt-Newlin, Jagannathan and Webber2020). Various frameworks have been proposed for cultural adaptation. Among these, the ecological validity model (EVM) by Bernal et al. (Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009), which recommends adaptations across eight domains (language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods and context), is widely used.

This study aimed to adapt PM+ to the context of refugee youth (16–18 years old) in the Netherlands while acknowledging the diversity of young refugees resettled in high-income countries. We developed a scalable EP module that can be integrated alongside the existing modules of the PM+ intervention. In this article, we describe the adaptation of PM+ with the EP module for refugee youth in the Netherlands, using a rapid qualitative assessment (RQA).

Methods

Setting and population

The total number of asylum applications in the Netherlands was recorded as 29,435 in 2019 and 19,132 in 2020 (IND, 2020). In 2019 and 2020, 1,470 asylum applications were submitted by young refugees aged between 16 and 18 years, with 1,005 of these being unaccompanied minors (IND, 2020). Most asylum applications in this age group were from Syria, followed by Morocco, Eritrea, Algeria, Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq (IND, 2020). For this study, we focused on the three most prevalent war-affected countries among this demographic (Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan).

Participants and data collection

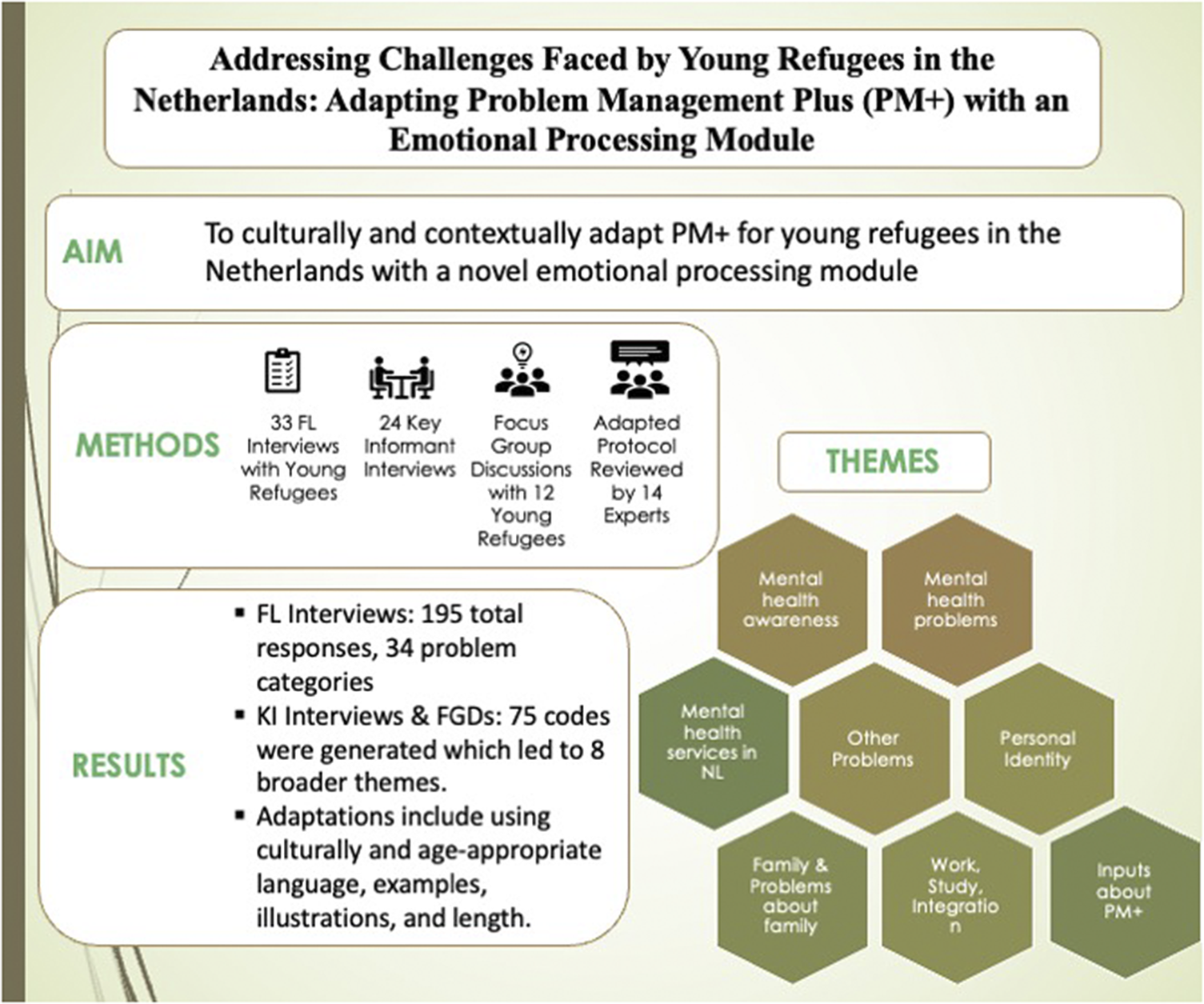

To adapt PM+ to the relevant context of young refugees living in the Netherlands, we conducted an RQA composed of three phases based on the Development, Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation (DIME) Model (Applied Mental Health Research Group, 2013). These three phases were (a) free listing (FL) interviews (n = 33), (b) key informant interviews (KI) (n = 24) and (c) focus group discussions (FGD) (n = 11 and one focused interview).

FL interviews are brief, structured interviews, which consist of a series of questions designed to elicit responses in a list format (Applied Mental Health Research Group, 2013). For FL interviews, a purposive sampling method called maximum variation in which participants are selected based on variations of some key characteristics (Suri, Reference Suri2011) was used. Relevant characteristics were country of origin, gender and age. Participants were young refugees, aged 16–18 years old and who had fled from Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan.

KI interviews were semi-structured interviews administered to professionals working with refugee youth (mental health professionals, teachers, NGO staff, etc.), policymakers and influential members of the target communities. Policymakers and professionals working with adolescents were interviewed to get more information on the problems of refugee adolescents. KIs from relevant communities were individuals without mental health training to gather insights reflecting commonly held community views on selected problems. A purposive sampling method was used; professionals and policymakers were contacted via professional networks, with a focus on their significant roles and expertise in refugee care and policies. KIs from the communities were identified either via young refugees’ responses from the FL interviews or through local organizations. Additionally, three separate FGDs were planned, one for each target refugee population (Syrian, Eritrean and Afghan). Purposive sampling and snowball sampling methods were used to recruit participants for FGDs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, recruitment relied on social media.

Procedure

This study was conducted in the Netherlands between October 2019 and July 2020. Ethical approval was received from the VUmc Medical Ethical Committee (2019.441). Three research assistants (one native Tigrinya speaker, one native Arabic speaker and one native Dari speaker) conducted interviews with refugee youth and key people. The researcher interviewed English-speaking KIs. Beforehand, they underwent a 3-day training which included principles of the DIME module, basic communication skills, interviewing, research ethics and data management. Two additional assistants (one Eritrean one Syrian) facilitated FGDs as co-facilitators after receiving training.

In FL interviews, participants were asked to list problems faced by their peers and common activities they are engaged in. Participants were prompted to list all problems affecting their communities and to further elaborate on identified mental health and psychosocial issues. Additionally, the participants were asked to identify influential members of their communities for subsequent KI interviews. The second part of the interviews centered on the daily activities of their peers caring for themselves, their families and their communities.

Separate topic lists were prepared for the semi-structured KI interviews with professionals working with refugee youth, policymakers and key people from the communities. Professional and policymaker interviews addressed refugee youth issues, mental health literacy, care-seeking behaviors, the Dutch mental health system and opinions on PM+ implementation. KIs from communities focused on three priority problems identified from FL interviews within each cultural group, covering problem characteristics, perceived causes of mental health problems in the community, effects on individuals and ideal solutions with adequate resources.

The goals of the FGDs were to (a) expand on the responses collected during the free listing interviews, (b) obtain participants’ opinions on how PM+ will be best implemented for their peers, (c) obtain information on the health care-seeking behaviors and (d) see if there are differences between the three communities regarding above-listed issues. The FGDs were divided into three key sections: first, participants reviewed FL interview outcomes and added overlooked aspects; second, they discussed help-seeking behaviors among their peers; and finally, the PM+ intervention was introduced for their input.

Initial interviews were conducted face-to-face. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic interrupting recruitment, the study was temporarily put on hold. With approval from the medical ethical review committee (METc) of the Amsterdam UMC, the remaining interviews with refugee youth, KIs and FGDs were conducted via teleconferencing. Remote interviews were conducted with the Skype for Business program (Version 7.0.2046.116, 2019), which allowed encrypted network communications.

Participants provided informed consent before the interviews. All forms were prepared in English and translated into Arabic, Tigrinya and Dari. Participants were informed that their answers would be confidential, all personal information would be pseudonymized and they could opt out without explanation. Following the transition to teleconferencing, informed consent was obtained orally and was recorded with a professional audio recorder separately from the interview responses and securely stored in an encrypted environment.

Interviews with refugee youth and refugee key people were carried out in their native languages. Detailed notes were taken during FL interviews by research assistants; no audio recordings were made to avoid discomfort. Similarly, during FGDs, co-facilitators took detailed notes, and no audio recording was taken. All KIs were recorded on an audio recorder and transcribed verbatim. Non-English interviews were translated into English post-transcription. KI interviews took approximately 45 min and FGDs took 1 to 1.5 h. Refugee youth and refugee KIs received €10 vouchers per hour for their participation.

Intervention

PM+ is a brief and transdiagnostic psychological intervention that relies on task-shifting. It was developed by the WHO for people who have experienced adversities (WHO, 2016). The individual PM+ consists of five 90-min sessions and includes four main strategies derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In each session, a new strategy is introduced and previously introduced strategies are practiced. Session 1 focuses on stress management, session 2 on managing problems, session 3 on behavioral activation, session 4 on strengthening social support and session 5 on relapse prevention.

As part of a wider study (Alozkan Sever et al., Reference Alozkan Sever, Cuijpers, Mittendorfer-Rutz, Bryant, Dawson, Holmes, Mooren, Norredam and Sijbrandij2021), we developed a new module for PM+, named “Managing Emotions and Memories.” This module helps participants to discuss challenging emotions and memories across multiple sessions for effective processing. The initial draft of the module was prepared in parallel with the data collection process and introduced to refugee youth during the FGDs. Facilitators explained the module’s aim and its components. They then invited participants to provide feedback, particularly regarding the metaphors employed to represent life narratives (namely, a puzzle or rollercoaster). Insights from PM+ discussions significantly shaped the module, influencing its structure, language and duration.

The initial module, along with the adapted PM+ protocol, was shared with 14 experts in the fields of child psychotherapy and psychiatry or refugee mental health care. Their feedback and evaluation led to revisions of the module. These changes included modifications to the length of the psychoeducational section, the use of metaphors to explain traumatic responses, the addition of grounding exercise within the stress management segment, as well as recommendations for the training of helpers. Subsequently, the revised module underwent further refinement before finalization, incorporating insights provided by these experts.

In the “Managing Emotions and Memories” module, participants are asked to think about all their memories as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and select three significant ones, including distressing memory. Additionally, participants recall two positive memories, as research indicates that focusing on positive memories can improve mental health and reduce PTSD severity (Contractor et al., Reference Contractor, Weiss and Forkus2021). These positive memories can include everyday events (e.g. “the day I helped my sister and made her happy”) or any other positive experiences that made the participants feel good about themselves. The EP module is carried out over a total of three sessions. In session 3, after reviewing the previous weeks, 30 min are dedicated to the EP module, followed by a 10-min stress reduction exercise (grounding). In the subsequent weeks, the module is repeated, with 15 min allocated to it, followed by a 10-min stress reduction exercise (grounding). In sessions 3–5, participants imagine those memories and talk about them in detail. Furthermore, participants are asked to evaluate their emotions before and after discussing the distressing memory. This distressing event should be a significant adverse event with a negative emotional impact for the youngster but does not need to represent the worst event. In session 5, they envision their “good-enough self” 5 years from now. By discussing these life events in terms of emotions, thoughts and future expectations, the module aims to process difficult emotions and foster hope. This adapted PM+ intervention comprises six 75-min sessions, with the new module introduced in session 3 and practiced in sessions 4 and 5.

The intervention is delivered by trained nonprofessionals (helpers) from the same cultural backgrounds as participants, in their native language. These helpers receive a 9-day training which focuses on the core strategies of PM+, common mental health problems, basic counseling skills and strategies on self-care as well as the new module. After completing one practice case, helpers start working with the participants and receive supervision from two trained PM+ supervisors throughout the implementation.

Data analysis

KI and FGD transcripts were entered in ATLAS.ti (Version 8; Scientific Software Development GmbH, 1997) for analyses. FL interview data guided the selection of problem topics for KI interviews and FGDs. To generate a response list, responses were categorized separately for each cultural group, similar responses were grouped and unclear ones were discussed with research assistants (Table 1). Codes were generated inductively in ATLAS.ti using KI interviews and FGD transcripts. FGD data were analyzed at the group level for each cultural group. The same codes generated during the coding of KIs were used for analyzing FGDs. The co-occurrence function and network analyses of ATLAS.ti were used to understand which codes frequently appear together and to create broader themes. All subsequent adaptations of the intervention were based on the information collected during the study and were guided by the EVM (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009).

Table 1. Problems faced by refugee youth

Abbreviations: AFG, Afghanistan; ERT, Eritrea; SYR, Syria.

Results

FL interviews provided insights used to shape KIs and FGDs. A total of 33 young refugees from Syria (n = 10), Eritrea (n = 16) and Afghanistan (n = 7) were interviewed. Analyses highlighted 34 problem categories and 195 responses across all cultural groups. Primary challenges included Dutch language difficulties, educational issues and loneliness, but variations existed among cultural groups. Syrians faced challenges with education and language barriers, while Eritreans emphasized stress, family separation and concerns about alcohol, drugs and suicide. Afghans underlined problems with receiving legal status in the Netherlands and cultural differences. Despite coping mechanisms such as sports, hobbies and socializing, some turned into less adaptive coping strategies such as smoking or alcohol. Many contributed to family and community through various activities. These FL findings aligned with information conveyed during FGDs and informed subsequent KI interviews (see Table 1).

We interviewed KI professionals working with refugee youth (n = 9), policymakers (n = 5) and 10 key people from the communities (three Syrians, four Eritreans and three Afghans). FGD participants were recruited through social media and local organizations. Two separate sessions were conducted: one with Eritrean youth (n = 6) and another with Syrian youth (n = 5). Despite using identical recruitment strategies across three cultural groups, we only recruited one Afghan participant and conducted a focused interview using the FGD questions. Data from the KI interviews and FGDs were analyzed together and based on them 75 codes were generated, leading to the emergence of eight broader themes. These themes are summarized below, with illustrative quotes for each theme presented in Table 2. The following broader topics were identified:

-

1) Mental health problems: The most frequently mentioned problems were stress, loneliness, traumatic experiences, feelings of isolation and problems related to alcohol and drug use. Stress was mostly mentioned alongside legal status in the Netherlands, education, integration and adaptation. Among the three groups, Afghans were concerned about their asylum status in the Netherlands most frequently. Concentration problems and isolation were often mentioned along with stress. Loneliness often co-occurred with cultural differences, language and isolation from the host community. Isolation often co-occurred with depression. Drugs and alcohol were mentioned as a coping mechanism for some youth (FL and KI from communities).

-

2) Mental health awareness: Most KIs agreed that the mental health knowledge and awareness of refugee youth was low. Help-seeking often co-occurred with the following codes: cultural differences, stigma, shame and trust. Eritrean and Afghan key people mentioned that talking about mental health problems is viewed as something to be ashamed of. In FGDs, both cultural groups mentioned girls tend to seek help more than boys. Syrians emphasized the cultural pressure on men to appear strong, which discourages help-seeking. Afghans expressed fear of jeopardizing asylum status by seeking mental health care. According to the participants, to reach youth about participating in the PM+ program it is important to work with key people from the communities.

-

3) Mental health services in the Netherlands: Many professionals and policymakers stated the need for more culturally sensitive treatments. According to them, there are culturally sensitive treatments, but they are not available across the Netherlands and vary widely according to the region. They also mentioned that coordination should be better between the different parties who work closely with refugee youth. Finally, they mentioned long waiting lists for services, which poses a significant challenge in accessing care.

-

4) Personal identity: Culture was deemed to be an important determinant of personal identity. According to the key people from the communities and inputs from FGDs, gender differences potentially affect help-seeking behavior (males showing less inclination to seek help) and adaptation (girls exhibiting greater ease in adaptation). Moreover, all three groups mentioned a stronger inclination toward collectivistic norms compared to Dutch cultural norms.

-

5) Family and problems related to family: Another recurring theme from the interviews was the issues and challenges regarding family. For all three groups, missing family and close friends was a common issue as reported by young refugees. According to the KI professionals, this was more pronounced among unaccompanied youth who are without parents or guardians in the Netherlands, this seems like an important stressor. Furthermore, the prolonged and uncertain nature of the family reunification process compounded this stress, adding to their emotional burden. Comparatively, for Syrian youth, cultural clashes seemed to be a significant issue, possibly because they are mostly here with their families. During the FL interviews, several participants mentioned that young people want to live independently, while their parents do not permit it, leading to disagreements. KIs from the communities reported their impression that parents are concerned that their children will “become too Westernized” and potentially experience a detachment from their cultural heritage. Meanwhile, according to the KIs, youth seem to be more inclined to behave more like their native peers.

-

6) Work, study and integration: An important challenge faced by youth from all three groups seems to be learning the Dutch language. Problems related to language were often mentioned in the context of integration and adaptation, which also appear to be linked to seeking assistance and feelings of loneliness. Refugee youth, as noted in interviews, often lack adequate time to rest and recover from their difficult journey (KI professionals). They start courses on language and integration, which can be challenging after difficult life events they have endured. Moreover, the loan extended by the government for Dutch language education becomes a substantial source of stress, since they need to repay it if they fail to pass language exams. This pressure to learn the language quickly seems to add an extra burden, making the learning process even more stressful. Most participants mentioned if the youth could go to school or work, they would feel less alone and isolate themselves less (FL). However, the ones who are already in the education system also face challenges such as different teaching methods, being placed in a lower academic level, encountering unfamiliar school subjects, language barriers and lack of support (FL). Additionally, delays in starting school and the nonrecognition of diplomas cause further frustration. For example, one participant stated, “We have to do everything alone and we are not helped,” while another noted, “Because the education system differs, your diplomas are not recognized, causing delays or cancelation.”

-

7) Other problems: The most notable additional challenges were issues related to one’s legal status in the Netherlands, unrealistic pre-arrival expectations and financial constraints. Many young refugees expected life in the Netherlands to be easier, including better education, quicker employment and smoother cultural integration. However, these unfulfilled expectations, combined with status-related challenges, may have been a source of stress.

-

8) Inputs about PM+: KI and FGD participants positively received the PM+ program, considering it a valuable addition to existing interventions, after receiving information about its content. KIs highlighted its potential in addressing a treatment gap within mental health interventions available. Participants provided varied feedback on several aspects of the program. Preferences regarding the program format – individual or group sessions – were divided, with considerations for sensitivity of topics discussed in such programs leading to suggestions for the availability of both formats. Shorter sessions were favored over longer ones. Involving parents or holding family sessions was seen as beneficial. Trust was highlighted as pivotal in how the PM+ program and the helpers would be perceived. Some emphasized the importance of cultural background alignment with the helper, while others preferred specialists or individuals of Dutch origin for increased trust (FGD). The majority mentioned that helper gender was not a crucial factor (FGD).

Table 2. Findings about eight themes and quotes

Findings from the study led to several adaptations in the generic PM+ protocol and its delivery (see Table 3). The final intervention, individual PM+, consisted of six 75-min sessions, available either in person or via teleconferencing. The term ‘client’ was replaced with ‘participant’ across the manual. Activities predominantly pursued by young refugees, such as internet use, sports and biking, were included in the behavioral activation module. Cases were adapted to resonate more with the youth’s experiences. Insights from the interviews acknowledged the diversity of young refugees, highlighting common issues like cultural adaptation, while also noting specific challenges such as family conflicts among Syrians and loneliness experienced by Eritrean and Afghan youth traveling alone. These distinctions informed recommendations for targeted training and supervision processes.

Table 3. Example adaptations made in line with the Bernal framework

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate challenges encountered by young refugees arriving in the Netherlands to inform the adaptation of the PM+ individual and the newly developed EP module for use in young people with a refugee background. To achieve this, we conducted FL interviews, KI interviews and FGDs among Syrian, Eritrean and Afghan young refugees (16–18 years old) and community members and professionals knowledgeable about young refugees in the Netherlands. Our aims while implementing this assessment were to identify problems encountered by refugee youth in the Netherlands, grasp concepts such as health and distress through the lens of their cultural backgrounds and acquire valuable information regarding the implementation of PM+ with the new EP module.

Both FL interviews and KI interviews revealed that the primary challenge for young refugees in the Netherlands revolves around difficulties in learning the language. This was a common issue expressed among all three cultural groups in the study impacting their daily lives, integration and likely contributing to feelings of isolation. This finding aligns with previous research showing that refugees consider language proficiency a key factor in integration (Earnest et al., Reference Earnest, Mansi, Bayati, Earnest and Thompson2015). Language proficiency has a special importance since many studies have also proved its connection with mental health problems. Lower language proficiency seems to be associated with higher mental health problems in migrant populations (Montemitro et al., Reference Montemitro, D’Andrea, Cesa, Martinotti, Pettorruso, Di Giannantonio, Muratori and Tarricone2021), and this relationship is more pronounced in refugee children and adolescents (Fazel et al., Reference Fazel, Wheeler and Danesh2005). While our study does not definitively link language struggles to increased mental health issues, it highlights the need for further investigation. The process of integration for refugees involves passing Dutch language exams, which many refugees prepare for with a loan (DUO, n.d.). However, this loan adds stress to young refugees’ lives, potentially overwhelming them with immediate responsibilities before addressing their pre-migration challenges as reported by the participants in our study (FL interviews and KIs).

For all three groups, educational challenges were mentioned by young refugees (FL interviews and FGDs), notably differences in teaching styles from their respective countries. This insight is important since teachers’ understanding of cultural backgrounds and facilitating culturally appropriate school transitions are recognized as valuable resources in school adaptation (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Minhas and Paxton2016). Moreover, young refugees in our study emphasized the importance of continuing their education, particularly for their integration (FL). Similarly, a study conducted in the Netherlands with refugee youth reported that schooling is seen as both crucial for adaptation and a strategy to cope with traumatic memories, yet it also serves as a source of stress (Sleijpen et al., Reference Sleijpen, Mooren, Kleber and Boeije2017).

Our research revealed that refugee youth, regardless of cultural background, often experience loneliness, stress and low mood. Eritrean and Afghan youth mentioned more frequently loneliness and longing for their families and friends back home. It is known that family reunions play a vital role in improving the well-being of unaccompanied minors (Fegert et al., Reference Fegert, Sukale, Brown, Hodes, Gau and De Vries2018). Similarly, the participants in our study mentioned prolonged waiting periods for family reunification is a stress factor for them (FL). Additionally, Syrian youth highlighted conflicts with parents due to cultural differences, reflecting challenges in parenting after resettlement. Some participants also mentioned that the cultural clashes between Dutch and Syrian norms led to tensions within families (KI Syrians). These conflicts with families are anticipated considering the previous studies which have consistently highlighted challenges in parenting following resettlement in a new country (Merry et al., Reference Merry, Pelaez and Edwards2017; Pangas et al., Reference Pangas, Ogunsiji, Elmir, Raman, Liamputtong, Burns, Dahlen and Schmied2019; Västhagen et al., Reference Västhagen, Özdemir, Ghaderi, Kimber, Giles, Bayram Özdemir, Oppedal and Enebrink2022). This study is not equipped to understand why distinct cultural groups highlighted specific issues, possibly influenced by family presence, the refugee status process and urgent concerns unique to each group.

The insights from this study prompted several adaptations in the PM+ protocol. The majority of the suggested adaptations were in the domains of language (such as not using technical words, using youth-friendly metaphors, translation of short protocols and the worksheets into the native language), context (offering online sessions or reimbursing travel costs for more accessibility, sending additional reminders for the sessions, flexibility in scheduling the sessions) and content (adding a new module for EP, adding a new technique, adapting the case examples, adding activities young people engage in) of the intervention. The adaptations we implemented closely resemble those highlighted in a systematic review that emphasized cultural modifications in depression interventions, mostly concentrating on language, context and persons domains (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Jotheeswaran, Nadkarni, Hollon, King, Jordans, Rahman, Verdeli, Araya and Patel2014). Additionally, we aimed to enhance PM+ by incorporating an EP component. The development of this component was enriched by the inputs of the expert panel and participants of FGDs. There is growing body of evidence about task-shifting approaches (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Uphoff, Singh, Thapa Pachya, Abdulmalik and van Ginneken2020; van Ginneken et al., Reference van Ginneken, Chin, Lim, Ussif, Singh, Shahmalak, Purgato, Rojas-García, Uphoff, McMullen, Foss, Thapa Pachya, Rashidian, Borghesani, Henschke, Chong and Lewin2021). Studies show that trauma-focused treatments like trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT; Cohen & Mannarino, Reference Cohen and Mannarino2008) and narrative exposure therapy (NET; Schauer et al., Reference Schauer, Neuner and Elbert2005) can be effectively used to treat PTSD treatment in refugee populations, even when delivered by nonprofessional helpers (Goninon et al., Reference Goninon, Kannis-Dymand, Sonderegger, Mugisha and Lovell2021; Ellis and Jones, Reference Ellis and Jones2022). However, there is heterogeneity in the findings, especially for NET (Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Tedeschi, Cuijpers, Del Giovane, Kip, Morina, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Purgato, Ricciardi, Sijbrandij, Tol and Barbui2021). Additionally, neither TF-CBT nor NET are transdiagnostic, as they specifically target PTSD symptoms, nor scalable as they require more extensive training and consist of more sessions (8–16 sessions). Our aim in developing the new EP Module was to contribute to the literature by investigating the feasibility of delivering elements targeting difficult life events as a part of a transdiagnostic and scalable intervention.

While this study offers valuable insights into the challenges faced by refugee youth and proposes a scalable trauma processing module within an effective intervention, it faces several limitations. Firstly, despite efforts to achieve maximum variation in sampling across cultural groups, not all groups are equally represented. Recruiting Afghan youth for FLs and FGDs proved challenging, resulting in their underrepresentation in the sample and hindering our ability to draw strong conclusions about this group. This may be due to the smaller Afghan population in the Netherlands compared to the Syrians and Eritreans, making recruitment more difficult. Although an expert group familiar with young refugees reviewed and provided feedback on the adapted protocol, time constraints prevented us from conducting additional cognitive interviews with local community members regarding the final version. Due to these limitations, it is important to underline the limited generalizability of our findings. However, we believe that despite these limitations, the finalized protocol represents an adapted PM+ protocol, with an integrated new EP module, tailored to the unique context and challenges faced by refugee youth in the Netherlands. Future research should focus on larger and more diverse samples, incorporate both qualitative and quantitative methodologies and involve multiple systems such as family, school and friends to comprehensively understand the multifaceted challenges encountered by young refugees and how these might inform intervention development. Additionally, it is important for researchers to transparently document and share the qualitative and formative processes undertaken before testing interventions to enhance the reproducibility and transparency of future studies.

Conclusion

To conclude, our study provided valuable insights into the challenges faced by refugee youth in the Netherlands, highlighting language barriers, educational challenges and integration. These findings informed the adaptation of the PM+ intervention, including a new EP module, tailored to address these specific issues. The adapted PM+ protocol now includes context-specific modifications and language, as well as additional support mechanisms. The adapted PM+ intervention, incorporating the novel EP module, requires piloting and testing in randomized controlled trials to investigate its feasibility and efficacy, ensuring it effectively meets the unique needs of refugee youth.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.93.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank to all participants whose input was invaluable in this study. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude to the expert panel who provided their valuable feedback on the newly written EP module and the adapted protocol. Additionally, we thank Yenovk Zakarian, Michael Matewos Abraham and Sahar Zohouri for their efforts in the recruitment and conducting interviews with the participants.

Author contributions

C.A.S. is the primary researcher for this study, responsible for the data collection, analyses and drafting of this manuscript. M.S. is the principal investigator of this study, conceptualized the study, acquired funding and supervised the study and writing process of this manuscript. P.C. co-supervised this study and reviewed the manuscript. E.M.R. is the coordinator of the REMAIN Project, which this study is a part of. R.A.B. and K.S.D. collaborated with C.A.S. and M.S. in writing the novel EP module introduced in this study. A.A. reviewed the manuscript and helped with interpreting the findings. All authors have made substantial contributions to the revision of the drafted manuscript and approved the final version.

Financial support

This study was funded by Swedish Research Council (Grant No. 2018-05783).

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study has been reviewed Medical Ethical Committee of VUmc (2019.441) and embedded in the Amsterdam Public Health (APH) Research Institute under Mental Health research program (SQC2020-016).

Comments

To whom it may concern,

We are writing to submit an original research article entitled “Addressing Challenges Faced by Young Refugees in the Netherlands: Adapting Problem Management Plus (PM+) with an Emotional Processing Module” for consideration by The Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health Journal. We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

In this study, we describe the cultural and contextual adaptation process of the Problem Management Plus (PM+) intervention for young refugees living in the Netherlands. Our study is novel in its approach as it not only summarizes the cultural and contextual adaptation process of the PM+ intervention but also introduces a newly developed emotional processing module tailored specifically for young refugees. By employing rapid qualitative assessment that includes free listing interviews with young refugees, and key informant interviews with professionals, policymakers, and knowledgeable individuals from the communities, as well as focus group discussions, we were able to gain invaluable insights into the problems and needs of our target population. In parallel to the qualitative assessment, we developed a novel module to incorporate into the PM+ intervention for emotional processing to better address the needs of young refugees who have been exposed to several challenging past events.

We believe that our manuscript will contribute significantly to the field of global mental health by providing valuable insights into the adaptation and enhancement of evidence-based scalable interventions for young refugee populations.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please address all correspondence concerning this manuscript to me at c.alozkan@vu.nl.

Thank you for your consideration of this manuscript.

Sincerely,

Cansu Alozkan Sever, MA

Department of Clinical, Neuro- and Developmental Psychology

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

WHO Collaborating Center for Research and Dissemination of Psychological Interventions

Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute