Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 800,000 people die by suicide each year worldwide [1]. Suicide and suicide attempts (SA) are major public health problems, representing an economic burden [Reference Shepard, Gurewich, Lwin, Reed and Silverman2,Reference Vinet, Le Jeanic, Lefèvre, Quelen and Chevreul3] and a great emotional burden, impacting families and relatives. SA are nearly 20 times more common than suicide deaths [4], and history of SA is predictive of subsequent attempts and risk of death by suicide (which typically occurs after several repeated attempts) [4,Reference Wasserman, Rihmer, Rujescu, Sarchiapone, Sokolowski and Titelman5]. The risk of complete suicide for people who have already had a previous history of SA is higher individuals with a single suicide attempt [Reference Weiner, Richmond, Conigliaro and Wiebe6,Reference Bostwick, Pabbati, Geske and McKean7]; this risk increases with each SA and remains high for more than 30 years [Reference Haw, Bergen, Casey and Hawton8]. According to Aresman et al., nearly half of repeat events occur within the first 3 months after the initial attempt and nearly two thirds (64%) within the first 6 months [Reference Arensman, Griffin, Corcoran, O’Connor and Pirkis9]. The risk of recurrence is highest immediately after discharge from hospital, with one in three patients repeating the attempt within 30 days [Reference Kapur, Cooper, King-Hele, Webb, Lawlor and Rodway10].

It has been shown that the method used in the first SA is an important predictor of subsequent SA [Reference Elnour and Harrison11,Reference Runeson, Tidemalm, Dahlin, Lichtenstein and Långström12]. A number of studies have found that recurrence rates are higher in people who presented with low lethal methods such as self-cutting, while those who used more lethal methods, such as hanging or drug over dose, had lower recurrence rates [Reference Madge, Hewitt, Hawton, de Wilde, Corcoran and Fekete13–Reference Perry, Corcoran, Fitzgerald, Keeley, Reulbach and Arensman15]. Conversely, other studies have found that subsequent SA were more likely to have occurred among people who use high-lethal methods in the index attempt (such as poisoning by domestically used gas, poisoning by other gases and vapors, hanging, drowning, firearms, air guns and explosives, jumping from high places, and other unspecified means) [Reference Huang, Wu, Chen and Wang16].

Given all of these characteristics, the implementation of recidivism prevention techniques is important. Among the many elements to be considered, the recommendations recommend monitoring programs such as maintaining contact at hospital discharge after a SA [17,18]. These monitoring programs are commonly referred to as “brief contact interventions” (BCIs) [Reference Milner, Carter, Pirkis, Robinson and Spittal19,Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Kawanishi, Yonemoto, Sugimoto and Furuno20]. These BCIs include: telephone recontact [Reference Vaiva, Vaiva, Ducrocq, Meyer, Mathieu and Philippe21], issuing a “resource card” mentioning the call number of a professional crisis manager [Reference Evans, Evans, Morgan, Hayward and Gunnell22]; sending letters written by a person who met the suicidal patient during a hospital stay [Reference Motto and Bostrom23]; sending postcards [Reference Carter, Clover, Whyte, Dawson and D’Este24]; and sending text messages to maintain contact [Reference Berrouiguet, Alavi, Vaiva, Courtet, Baca-García and Vidailhet25]. Several studies have shown the effectiveness of BCIs in reducing SA [Reference Fleischmann26–Reference Cebrià, Parra, Pàmias, Escayola, García-Parés and Puntí28]. Bertolote et al. found the efficacy of phone calls on suicide mortality, but did not demonstrate this effect on SA, contrasting with Cebrià et al. who found a decrease in the number of suicide reattempt related to phone calls, agree with those of a study on telephone follow-up as a protective factor against repeated suicide attempt [Reference Bertolote and De Leo27,Reference Cebrià, Parra, Pàmias, Escayola, García-Parés and Puntí28]. Fleischmann et al. found a significant reduction in death by suicide among suicide attempters, based on continuous communication in combination with standard treatments [Reference Fleischmann26].

In 2015, Milner et al. and Inagaki et al. published simultaneously two meta-analyses evaluating the effect of BCIs on people who have done SA. Their converging findings suggested that patients benefited from recontact procedures, with significantly lower relapse and suicide rates compared to controls treated as usual [Reference Milner, Carter, Pirkis, Robinson and Spittal19,Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Kawanishi, Yonemoto, Sugimoto and Furuno20]. According to the results of Milner et al., BCIs were effective on the number of suicide reattempts per person (incidence rate ratio = 0.66) [Reference Milner, Carter, Pirkis, Robinson and Spittal19]; according to the meta-analysis of Inagaki et al., BCIs were effective to prevent a repeat suicide attempt at 12 months (relative risk = 0.83) [Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Kawanishi, Yonemoto, Sugimoto and Furuno20].

The well documented effectiveness of BCI procedures, as well as their low cost and ease of deployment, are strong arguments in favor of their integration into a comprehensive multilevel prevention strategy [Reference Fleischmann, Arensman, Berman, Carli, De Leo and Hadlaczky29]. Furthermore, by taking into consideration the strengths and limitations of each of these strategies (e.g., crisis card had a significant effect for first attempters than others) [Reference Vaiva, Vaiva, Ducrocq, Meyer, Mathieu and Philippe21–Reference Carter, Clover, Whyte, Dawson and D’Este24], a combination of BCIs has been proposed to allow for flexible and effective implementation [Reference Messiah, Notredame, Demarty, Duhem and Vaiva30,Reference Vaiva, Walter, Al Arab, Courtet, Bellivier and Demarty31]. This is the case of the VigilanS program [Reference Duhem, Berrouiguet, Debien, Ducrocq, Demarty and Messiah32–Reference Fossi Djembi, Vaiva, Debien, Duhem, Demarty and Koudou34].

Created in 2014 in collaboration with the hospitals of Nord-Pas de Calais, and operational since 2015, VigilanS allows to contact any suicidal person immediately after a SA, by a team of mental health professionals specially trained in suicide crises management. It is a regional BCI, combining several interventions: a resource card, telephone calls, and sending postcards [Reference Duhem, Berrouiguet, Debien, Ducrocq, Demarty and Messiah32]. Unlike clinical trials, VigilanS is implemented in the entire population, under real conditions. Studies on BCIs are generally clinical trial studies, but the major disadvantage is the lack of generalization to the whole population, due to significant selection bias [Reference Inagaki, Kawashima, Yonemoto and Yamada35]. To our knowledge, there is a lack of literature on regionally implemented post-attempt BCIs. Previous studies have been done on VigilanS. These previous studies on VigilanS concerned the description of VigilanS in its functioning and implementation, and the relationship between the variation in SA and VigilanS penetration (proportion of people who had a suicide attempt and were included in VigilanS, relative to all people who had a suicide attempt regardless of their inclusion in VigilanS), in Nord-Pas de Calais hospitals (NPC) [Reference Jardon, Debien, Duhem, Morgiève, Ducrocq and Vaiva33,Reference Fossi Djembi, Vaiva, Debien, Duhem, Demarty and Koudou34]. Nevertheless, the description of the profile of the patients followed by VigilanS as well as the analysis of suicide reattempt after inclusion in VigilanS are important analyses that have not yet been explored in these previous studies conducted on VigilanS. This is therefore the point of our article.

Objective

The objective of this article was to study suicide reattempt in patients followed for at least 6 months in VigilanS. More specifically, the aim was to describe the characteristics of the patients, to estimate the mean time between suicidal iterations, and to identify the profiles of patients who had a suicide reattempt compared to other patients.

Methods

Description of the VigilanS system

VigilanS is a 6-month monitoring program, after a SA. As soon as the patient is discharged from the emergency room, he or she receives a resource card with the VigilanS number on it. From this point onwards, VigilanS takes charge of the intervention and patients follow-up, which complement the routine care provided by the participating centers, for a 6-month period.

Telephone calls between the 10th and 21st day (D10–D21)

Between 10th and the 21st day after discharge from hospital (D10–D21), all non-primary suicide attempters are recalled because they are at high risk of doing a new SA. During the D10–D21 call, decisions are made, depending on the case at hand as judged by the calling professional: an emergency or a regular appointment is planned; a new telephone call is scheduled; personalized postcards are sent; these actions can be combined; or no further action is planned.

Six-month calls

At the 6th month, all patients (primary and non-primary suicide attempters) are called for an end of follow-up interview. A non-primary suicide attempter is a patient who have done at least one previous SA when included in VigilanS, and a primary suicide attempter is a patient who have done a first suicide attempt when included in VigilanS. Before each call, the patient is informed in advance of the call that will be made. If judged necessary by the calling clinician, the program can be extended for another 3 or 6 months. In case of a new SA during the follow-up period, the entire VigilanS program is reset for another 6 months. If a patient reiterates a SA after the follow-up period, (s)he re-enters VigilanS. There is no limit on the number of entries.

Other telephone calls during follow-up

In addition to these two systematic calls, intermediate calls are also made during the 6-month follow-up period. Intermediate calls are calls made at the initiative of VigilanS (outgoing calls) outside the two calls provided for by the program (at D10–D21 and at 6 months), or calls made by patients (incoming calls). A detailed description of the VigilanS intervention is published for more information [Reference Duhem, Berrouiguet, Debien, Ducrocq, Demarty and Messiah32,Reference Jardon, Debien, Duhem, Morgiève, Ducrocq and Vaiva33].

Patient selection

Our study was conducted on all the patients included in VigilanS over the period from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018 in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. July 1, 2019 marks the end of the follow-up of our study. Patients who died during the first stay follow-up (before the second inclusion in VigilanS) were excluded from the analysis.

Data processing

The same patient can be included several times in VigilanS in case of repeated SA. Therefore, the statistical units of analysis (SUA) can be either the SA that triggered an inclusion in VigilanS, with possibly several records per patient, or the patients, with a single record consisting of all successive inclusions, if any. For our study, the statistical units were the patients; for those who had multiple inclusions in VigilanS, the first inclusion was selected.

Statistical analysis

The outcome was suicide reattempt, and the explanatory variables were the characteristics of the patient at entry and during follow-up in VigilanS, at the first inclusion in VigilanS if there were several. The recurrence was identified by a second entry in VigilanS. The list of variables and description can be found in Appendices 1 and 2.

We performed three types of analyses: descriptive analyses, bivariate analyses, and multivariate analyses. A survival analysis was also done.

Descriptive analysis

A general description was made on all the patients in order to give the size of each variable, as well as on the non-primary suicide attempters successfully contacted during the D10–D21 call.

Survival analysis of suicide reattempt

As suicide reattempt is a time-dependent event, censored on the right, it was treated by survival analysis, performed by the Kaplan–Meyer method. This made it possible to estimate (a) the median time of suicide reattempt after inclusion in VigilanS; and (b) the rate of patients having reiterated at a given time.

The survival analysis of suicide reattempt included all patients selected in our study. The duration of follow-up depends on the last successful telephone call with the patient (difference between the SA date and the date of the last successful telephone). The last successful call can be either the last successful call made to the patient or received from the patient. For those with no successful telephone calls, the duration of follow-up depends on the end date of our study (difference between the SA date and the end date of the study “1st July 2019”). The event analyzed is the suicide reattempt, the time of occurrence of which is obtained by the difference between the date of the first SA and the date of the first suicide reattempt.

Bivariate and multivariate analysis

The event to be studied being time-dependent, we performed Cox models. The duration of follow-up concerns the difference between date of SA and the end date of the study “July 1, 2019”) for those who do not have the event; the difference between the date of the first SA and the date of the first suicidal reattempt for those who have the event.

Bivariate analysis was performed to study the relationship between two variables: dependent and independent. Variables whose p-value was less than 0.1 in bivariate analysis were selected for the multivariate analysis. For variables with multiple modalities, the global effect of the variable was also studied in order to include them in the multivariate analysis (global p-value less than 0.1). Analyses were adjusted for age and gender, which were considered as potentially confounding factors.

The multivariate analysis was performed using the multivariate Cox model. We used a step-by-step top-down selection. Before further interpreting the model and the significance of the effects, we tested the hypothesis of the model’s validity by analyzing residuals over time (time-dependent co-variables). According to this hypothesis of validity, a cox model is valid if the residuals are not time-depending.

A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, as well as a hazard ratio (HR) that did not include the value 1 in its 95% confidence interval. The software used was R, version 4.0.5.

Results

From January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2018, we had 10,666 patients, of which 905 patients (7.6%) had a suicide reattempt (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart for patient selection in the analysis.

Patient description

The mean age of all patients was 40.6 ± 15 years. Most patients were women (58.7%) and from the North (54.5%). The most frequent length of hospitalization was 1 day (48%) and the majority of SA was by voluntary drug intoxication (VDI) (83.2%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Description of patients at first entry into VigilanS.

Abbreviation: SA, suicide attempt.

a Means ± SD.

Concerning primary and non-primary suicide attempters, there were some variations: there were more women among non-primary suicide attempters than among the primary suicide attempters (61.4 vs. 56.3%), more alcoholics among non-primary suicide attempters than primary suicide attempters (54.6 vs. 48.5%), but fewer patients with a companion in the emergency room among the non-primary suicide attempters as opposed to the primary suicide attempters (69.9 vs. 79.0%). Calls made and received were higher among the non-primary suicide attempters than among the primary suicide attempters (Table 1).

Among the non-primary suicide attempters interviewed on D10–D21 call (Table 1), more than three fourth of patients needed help (77.4%) and more than half of the patients had postcards sent following this interview (62.8%). Apart from VigilanS, most patients were followed by a psychiatrist (65.8%).

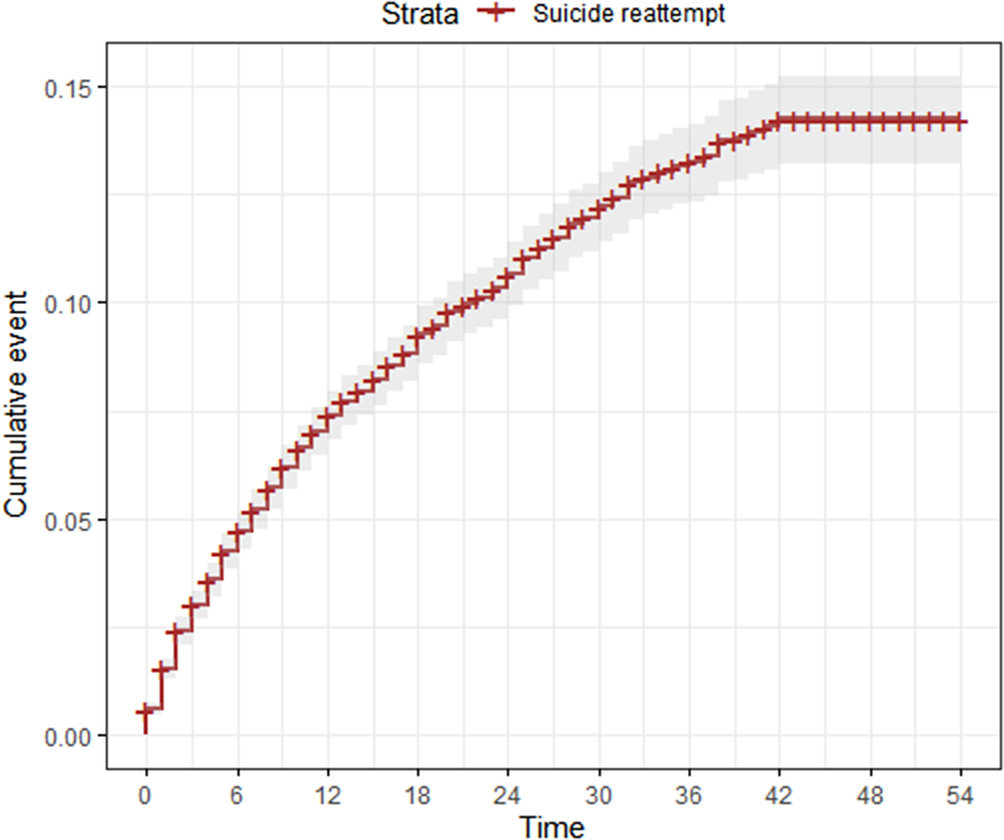

Suicide reattempt survival curve

The rate of suicide reattempt in our study was 8%. Figure 2 shows the survival analysis of suicide reattempt in all suicide attempters as a function of their length of follow-up in months. We see that nearly 26% of patients had a suicide reattempt during the first 6 months of follow-up, nearly 42% within 12 months. The mean time of suicide reattempt was 18 months.

Figure 2. Suicide reattempt survival analysis as a function of follow-up time in months (N = 10,666).

Bivariate analysis

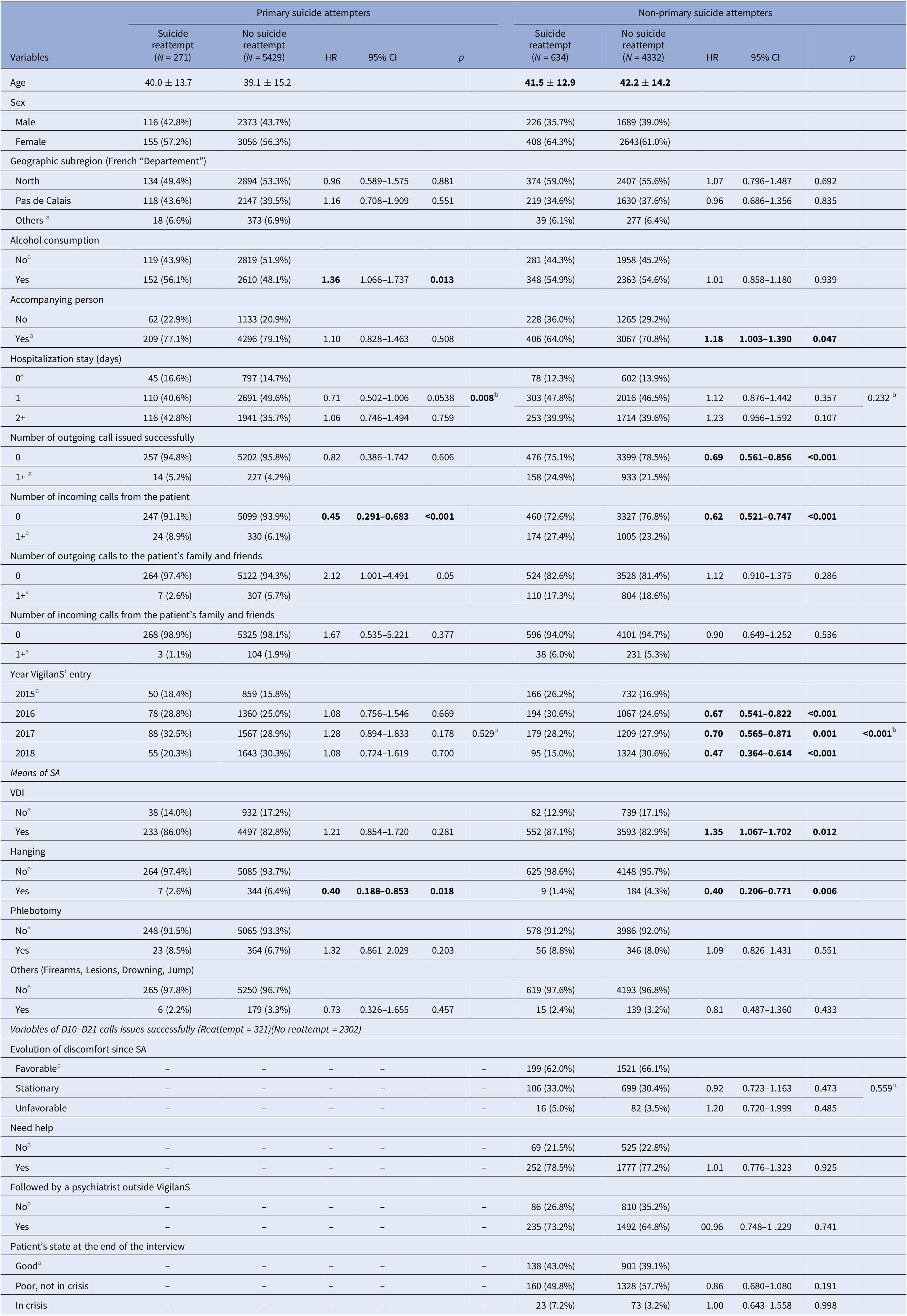

After adjusting for age and sex (Table 2), there was a significant relationship between suicide reattempt and: being a non-primary suicide attempter; regular alcohol use; being unaccompanied during the emergency room visit; no calls made to or received from the patient; no calls made to or receive from entourage; year of entry in VigilanS; means of suicide by VDI, hanging, and phlebotomy.

Table 2. Comparison of general characteristics of suicide reattempt and no suicide reattempt patients and simple age and sex-adjusted logistic regression.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SA, suicide attempt; VDI, voluntary drug intoxication.

a Means ± SD.

b Reference modality in the variable.

c Global p-value of the multimodality variable. Bold values: significant relationship with suicide reattempt

The variables significantly associated with suicide reattempt in primary suicide attempters were alcohol users; length of hospitalization; no calls received from the patient; means of SA by hanging (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of general characteristics of suicide reattempt and no suicide reattempt patients and simple age and sex-adjusted logistic regression.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SA, suicide attempt; VDI, voluntary drug intoxication.

a Reference modality in the variable.

b Global p-value of the multimodality variable. Bold values: significant relationship with suicide reattempt

In contrast, among non-primary suicide attempters, the variables significantly associated with suicide reattempt were: no presence of a companion during the visit to the emergency room; no calls made to and received from the patient; year of entry in VigilanS; means of SA by VDI and hanging (Table 3). Variables concerning the call at D10–D21 were not significant.

Multivariate analysis

After analyzing the validity of the model, the variable “years of entry into VigilanS” was not taken into account in the final model, because their residuals had a very strong relationship with time, making Cox’s model less valid. According to the model validity assumption, the residuals should not be time dependent. The year effect increases linearly with time. The other effects appear to be fixed (See “Appendices 3 and 4”).

In our multivariate analysis (Table 4), the patients at risk of suicide reattempt were non-primary suicide attempters (HR = 4.85); patients whose call was not made to their family and friends (HR = 1.23), and patients who attempted suicide by VDI (HR = 1.32) and phlebotomy (HR = 1.34). Alcohol consumption was identified as a risk factor for suicide reattempt in primary suicide attempters (HR = 1.26) and patients without a companion during the emergency room visit as a risk factor for suicide reattempt in non-primary suicide attempters (HR = 1.38).

Table 4. Multiple regression of suicide reattempt and no suicide reattempt patients.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; VDI, voluntary drug intoxication. Bold values: significant relationship with suicide reattempt

However, the protective factors identified were hanging (HR = 0.49, p = 0.008) and patients who did not make calls to VigilanS during follow-up (HR = 0.61, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Main findings and comparison with findings from other studies

Suicide reattempt is one of the important concerns in suicide prevention, as repetition can lead to final suicide. It is important to know which types of patients are at risk of suicide recurrence, especially when they have been followed by a post-attempted prevention program. In our study, the program is installed in hospitals in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. The interest and the originality of this study was to focus on a large population observed in real conditions.

The rate of suicide reattempt in our study was 8%, and the mean time of suicide reattempt according to our survival results was 18 months. This rate of suicide reattempt was lower to rates obtained in other studies. According to the study by Exbrayat et al. also concerning an BCI, the rate of reattempt among study patients was 12.6 and 21.2% in the study by Carter et al. [Reference Exbrayat, Coudrot, Gourdon, Gay, Sevos and Pellet36,Reference Pushpakumara, Thennakoon, Rajapakse, Abeysinghe and Dawson37]. Lilley et al. also found 17%, although survival analysis revealed a suicide reattempt rate of 33% of patients in the year following an episode [Reference Lilley, Owens, Horrocks, House, Noble and Bergen14], lower than our result, 42% in 1 year. In other studies, suicide reattempt occurred slightly earlier, within 3–6 months after SA [Reference Arensman, Griffin, Corcoran, O’Connor and Pirkis9,Reference Kwok, Yip, Gunnell, Kuo and Chen38–Reference Carter, Clover, Whyte, Dawson and D’Este40]. According to the study by Carter et al., more than half of the reattempt occur nearly 6 months after the intervention [Reference Pushpakumara, Thennakoon, Rajapakse, Abeysinghe and Dawson37]. This thus suggests the effectiveness of VigilanS on suicide reattempt, from the first entry into VigilanS. Maintaining contact is of great importance for the patient’s future.

Non-primary suicide attempters were four times more likely to repeat suicide than the primary suicide attempters. This result is similar to several studies, which have also shown that a history of SA is a risk factor for suicide reattempt [Reference Carroll, Metcalfe and Gunnell41–Reference Ribeiro, Franklin, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman and Chang44]. In the study by Ribeiro et al., non-primary suicide attempters were 3.6 times more likely to repeat suicide [Reference Ribeiro, Franklin, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman and Chang44], and the higher the number of previous SA, the higher the risk [Reference Park, Lee, Youn, Kim, Park and Kim43]. This risk of suicide reattempt identified in our study in non-primary suicide attempters supports the hypothesis that patients who have already made a failed SA have a high suicidal intention, and may have acquired the ability to engage in suicidal behavior with increased tolerance to physical pain and decreased fear of death, which may lead to a fatal suicide act [Reference van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner45,Reference Joiner46]. It is in this context that VigilanS has set up a specific telephone call to patient non-primary suicide attempters, between the 10th day and 21st day after their SA, because these patients are at high risk of suicide reattempt.

We found that the means used during SA were associated with suicide reattempt; patients who attempted suicide by VDI and Phlebotomy were more likely to have a suicide reattempt than those who used another method. However, those who attempted suicide by hanging, were less likely to have a suicide reattempt. This result is almost similar to that of Perry et al., who found that rates of recurrence were low in patients who used methods such as hanging, but also chemical poisoning, which is rather identified as a risk factor in our study [Reference Perry, Corcoran, Fitzgerald, Keeley, Reulbach and Arensman15]. According to Oflson et al., the risk of suicide reattempt did not differ significantly between patients who initially used violent (firearm-related methods and “other violent” methods) and nonviolent methods (poisoning or cutting) [Reference Olfson, Wall, Wang, Crystal, Gerhard and Blanco47]. These differences can be explained by the fact that these studies were carried out on a national level, unlike our study which was carried out on a regional level and the methods of attempted suicides may differ from one region to another.

Patients who had not made calls to VigilanS were identified as being at lower risk of suicide reattempt. Incoming intermediate calls (calls made outside D10–D21 call and 6-month call) are usually long calls from patients in need of help and/or listening, and outgoing intermediaries’ calls are often intended for patients at high risk of suicide, or for patients who have could not be reached in previous telephone calls. Regardless of the type of incoming or outgoing call, there is a risk of repeat suicide attempt in these patients, which necessitates the importance of paying special attention to these patients through telephone follow-ups. However, it was found that no call to the relatives was a risk factor for a new suicide attempt. This result shows the importance of family and friends in supporting suicidal patients, helping the patient to avoid making a new suicide attempt.

Other risk factors such as alcohol consumption and absence of a companion during his or her visit in the emergency room were specifically identified in primary suicide attempters and non-primary suicide attempters. Alcohol consumption is an important profile of SA. Nearly a quarter of suicide deaths are directly attributable to alcohol [48], which is often used in SA (both nonlethal and lethal) [Reference Kaplan, Giesbrecht, Caetano, Conner, Huguet and McFarland49–Reference Borges, Bagge, Cherpitel, Conner, Orozco and Rossow51]. Regarding the absence of a companion during his or her visit in the emergency room. The presence of a person around the patient, especially one with whom the patient shares many affinities, leads to less loneliness. Liu et al. also emphasize the importance of a relative. According to them, hopelessness and social support emerged as significant predictors of suicide reattempt [Reference Liu, Zhang and Sun52]. By Holma et al., a presence of partner is an important factor in protecting patients against from SA, in support [Reference Holma, Melartin, Haukka, Holma, Sokero and Isometsä53].

Strengths and weaknesses

However, our study had some limitations. It was based only on a limited number of patients, due to a large number of patients lost to follow-up (LFU) in VigilanS. More than half of the patients were LFU (no news from them during the program after several contact attempts). In addition, patients who died during the first follow-up were excluded from our study, which may have been due to a new suicide attempt or illness or other reason (95 patients). This may modify our estimate of the suicide reattempt rate. However, if there is a recurrence, then the patient re-enters VigilanS (unless the patient dies, is not hospitalized, or does his SA outside the NPC region, which is a minority). The recurrence is therefore correctly identified for a majority of patients.

For the survival analysis, the last successful telephone call was considered as the end date of the follow-up, and the end date of the study for those with no successful telephone calls. This variation of the date of the follow-up could influence the estimate of the mean duration of suicide reattempt.

Another limitation is that our population was based only on the hospital environment, and some of the SA in the population do not lead to hospitalization. In France, however, the proportion of nonhospitalized SA is small, around 8% [Reference Léon, Chan-Chee and du Roscoät54], but this can still pose a difficulty in generalizing our results to the entire population.

In addition, not all patients admitted to the emergency department during our study period were fully analyzed. Not all patients admitted to the Emergency Department included in VigilanS, and some patients who were not in the study may have different suicidal behaviors from those included in the study. This nonexhaustive inclusion may therefore influence our analyses, mainly the rate of suicide reattempt.

Analysis on the patient’s psychiatric profile would have been desirable but could not be carried out, as attempts to establish this profile proved too cumbersome in the context of a large-scale implanted program and were abandoned. It is still important to pay attention to other factors.

On the other hand, a strength of this study is the almost exhaustive collection over 4 years of data on patients passing through the care system following a SA, over an entire region. This study provides a baseline that can help in the design of suicide prevention interventions because, to our knowledge, no previous data on suicide reattempt among patients followed by a post-attempt system in France is available to allow comparisons. Our results provide knowledge on suicide reattempt, identify people at risk of suicide reattempt and allow for better post-suicide follow-up. In addition, the study evaluates the effectiveness VigilanS, which is based on a simple methodology that could easily be applied in other countries.

To conclude, after a SA, the risk suicide reattempt is present in some patients, especially non-primary suicide attempters with a very high risk of suicide reattempt. However, VigilanS plays an important role in post-attempt follow-up, with a low rate of suicide reattempt compared to the literature. VigilanS suggests the possibility of better identification of patients likely to repeat, and to strengthen prevention efforts in these populations.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of all investigators who contributed to our study.

Financial support

Larissa D. Fossi was supported by a fellowship from the Faculty of Medicine of Paris-Sud University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authorship contributions

All authors made significant contributions to this study and read and approved the final manuscript. Antoine Messiah and Guillaume Vaiva contributed to the conception, analysis, and critical revisions. Larissa D. Fossi contributed to the analysis, drafting of the manuscript, interpretation, and critical revisions. Christophe Debien and Anne-Laure Demarty contributed to the interpretation and critical revisions.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Larissa D. Fossi, with the permission of Guillaume Vaiva.

Ethical statement

The VigilanS study was authorized by the French Ministry of Health and approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes of Nord-Pas-de-Calais region (Ethics Committee). It was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03134885).

Abbreviations

- BCI

-

brief contact interventions

- CI

-

confidence interval

- D10–D21

-

call between the 10th and 21st days after SA

- HR

-

hazard ratio

- LFU

-

lost to follow-up

- p

-

p-value

- SA

-

suicide attempt

- SUA

-

statistical units of analysis

- VDI

-

voluntary drug intoxication

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

A. Appendix 1

General variables

B. Appendix 2

Variables at D10–D21 phone call (non-primary suicide attempters)

C. Appendix 3

Residuals from the initial model with the variable “Year”

The effect of the variable “Year VigilanS’ entry” increases linearly with time, unlike the other variables.

D. Appendix 4

Final model (residuals from the final model without the variable “Year VigilanS’ entry”)

The other effects appear fixed.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.