1. Introduction

That part of the UK fiscal framework, which determines how UK government (UKG) funding is allocated across the four home nations, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, has undergone profound change since 2012. The Scotland Act 2012 instigated some modest changes to Scotland’s tax powers. These were given further impetus in the Scotland Act 2016, which followed the 2014 independence referendum that had resulted in a relatively narrow victory for the ‘remain’ camp. Growing support for additional powers also led to increases in the fiscal powers of the Welsh Parliament as legislated in the 2014 and 2017 Wales Acts. The changes in Scotland and Wales were complex and still not complete at the time of writing in early 2022. Yet they mark a significant change from the status quo, with the ‘devolved governments’ (DGs) in Scotland, Wales and potentially Northern Ireland accepting additional fiscal risk in return for greater control over local funding streams (Fiscal Commission NI, 2021).

During this period of fiscal transition, the UK has also had to deal with two significant exogenous shocks—Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic. These have strained relations between the UKG and the DGs in different ways, and have tested the sustainability of the devolved fiscal frameworks.

Prior to Brexit, there was broad agreement around the functions or ‘competences’ of the UKG on the one hand, and the DGs on the other. Broadly, the DGs controlled education, health, local government and economic development within their jurisdictions, while welfare, foreign relations, macroeconomic management and so forth were the preserve of the UKG.Footnote 1 Brexit set in train a sequence of events that have challenged these assumptions. Further, the fiscal frameworks implicitly acknowledged that occasions might occur when additional support or borrowing powers might be offered to the DGs. But they did not anticipate the magnitude of the increases in public finance across all parts of the UK that were necessary to respond to the pandemic.

The changes to the fiscal framework, along with Brexit and the pandemic have both stretched the policy bandwidth of both the UKG and the DGs. Because many of the outcomes are contested, they have also widened opportunities for conflict and grievance leading to increased strains on the union.

In this article, we document recent changes in the fiscal arrangements affecting the DGs. We explain the complex way that these redistribute fiscal risk across the UK. We then separately discuss the stresses caused by the pandemic and Brexit to these inter-governmental fiscal flows. We argue that in response to the pandemic, ad hoc mechanisms had to be invoked to prevent fiscal crises among the DGs. Brexit has undermined the DG fiscal frameworks in a different way: competences previously assigned to the European Union were repatriated to the UK post–Brexit. These have mainly been retained by the UKG although previously the DGs had a significant role in their operation. This has caused conflict between the DGs and UKG with possible negative effects not only on the fiscal framework agreements but also on the political ties that bind the union together. The final section concludes by considering the stresses placed on the union by these various events and policy responses. It also examines whether proposals to take the heat out of such disputes are likely to succeed.

2. Developments in the fiscal framework 2016–2021

At the beginning of the last decade the DGs had relatively little autonomy over tax policy. The main exception to this picture was local tax policy, where the DGs determined the broad design of domestic property taxes (council tax in Scotland and Wales, and domestic rates in Northern Ireland) and the design and rates of commercial property taxes (non-domestic rates). As part of the legislation that governed its establishment, the Scottish Parliament also had the power to vary the basic rate of income tax by up to 3p in the pound via the Scottish Variable Rate (SVR), but never exercised this power. The Northern Ireland Executive also had the power to create new taxes, provided they substantively differed from those levied by the UKG, although again this power has never been exercised.

All three DGs therefore experienced high ‘vertical fiscal imbalances’. The vast majority of their budgets took the form of block grants provided by the UKG, the level of which was determined by the Barnett formula. Under this formula, which remains in place, the block grant each year is set equal to the block grant the previous year, plus a population share of the change in planned spending in England on the services devolved to the DG in question (termed ‘comparable spending’).Footnote 2 Thus, if spending on education in England, which is a fully comparable spending category, increases by £100, the Scottish block grant would increase by £9.60, given that its population is 9.6 per cent of England’s, with similar calculations determining the increase in the Welsh and Northern Irish block grants. Though in principle the DGs can spend these Barnett ‘consequentials’ as they see fit, for high profile areas such as health, they often pledge to pass on the funding to their equivalent services.

The UK’s high level of vertical fiscal imbalance reflects the centralised nature of the UK state relative to other advanced economies, an issue discussed in detail in McCann (Reference McCann2021). The OECD (2016) estimated that sub-national government revenues in the UK comprised 1.6 per cent of GDP and 5.9 per cent of total public tax revenue in 2014. This compares with OECD averages of 7 per cent of GDP and 31.6 per cent of public tax revenue.

A key moment for the subsequent evolution of the DGs tax powers and funding arrangements was the SNP victory in the 2007 Scottish Parliament election. In response, the unionist parties—Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrats—established the Calman Commission, with a remit to consider how to enhance the financial accountability of the Scottish Parliament, including through extending the Scottish Parliament’s tax and broader fiscal powers. The Commission’s recommendations included that the Scottish Parliament be given greater control over setting the rates of income tax and full control over Stamp Duty Land Tax, the Aggregates Levy, Landfill Tax and Air Passenger Duty.

Though some progress was made in implementing these powers, a further political development changed the course of fiscal arrangements again: the SNP’s majority in the Scottish Parliament elections in 2011 led to a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014. The result was a narrow victory for the ‘No’ campaign, but the political response from the UKG was to consider a further extension of fiscal powers in Scotland. The Smith Commission was established to consider this issue. It recommended that the Scottish Parliament be given power to set the rates and bands of income tax for Scottish taxpayers. The tax would continue to be administered by HMRC. It also proposed that VAT revenue raised in Scotland be shared between the Scottish and UKGs and that the Scottish Parliament be given control over disability-related welfare payments—Attendance Allowance, Personal Independence Payments, and so forth—and some other relatively small benefits (such as Winter Fuel Payments). The Smith Commission argued that these new fiscal powers would ‘strengthen the Scottish Parliament’s ability to pursue its own vision, goals and objectives’ and make the Scottish Parliament ‘more accountable and responsible for the effects of its policy decisions and their resulting benefits or costs’, ultimately making the parliament ‘more responsive, durable and stable’ (Smith Commission, 2014). The Scotland Act 2016 made the necessary legislative changes.

In Wales, the Holtham Commission (2010) and the Silk Commission (2012) proposed the Assembly Government should have powers to vary income tax rates, and to control those taxes—Stamp Duty, Landfill Tax, Air Passenger Duty and Aggregates Levy—that the Calman Commission recommended for Scotland. Echoing the language of the Calman Commission, the Silk Commission made the case for tax devolution on the basis of accountability:

Because the budget comes largely in a grant from the UK Parliament, the Welsh Government and National Assembly for Wales are not accountable to the Welsh electorate for how revenue is raised in the same way that they are for how it is spent… changes to the existing system could deliver greater responsibility and empowerment to the Welsh Government (Silk Commission, 2012 ).

The Wales Act 2017 modified income tax rules in Wales, reducing the rates collected by the UKG by 10p in each band. The Welsh Parliament was given powers to set a ‘Welsh’ rate for each band on top of the new lower UKG rates, with the revenues accruing to Wales. As in Scotland, HMRC continues to administer the tax. Two of the other taxes included in the Holtham proposals—Stamp Duty Land Tax and Landfill Tax—were also transferred to the Welsh Parliament in 2017.

In Northern Ireland, although there has been extensive discussion, little progress has been made to date in establishing new fiscal powers. Unlike in Scotland and Wales, corporation tax has been a particular focus of attention due to the difficulties that Northern Ireland has faced in competing with the Republic with its much lower corporation tax rates. The ability of the NI Executive to vary the headline rate of Corporation Tax in NI was legislated for at UK level in 2015, but has not yet been commenced. More recently, the Fiscal Commission NI was established in 2021 to review the scope to enhance the NI Assembly’s fiscal responsibilities and increase its ability to raise revenues to sustainably fund public services (Fiscal Commission NI, 2021).

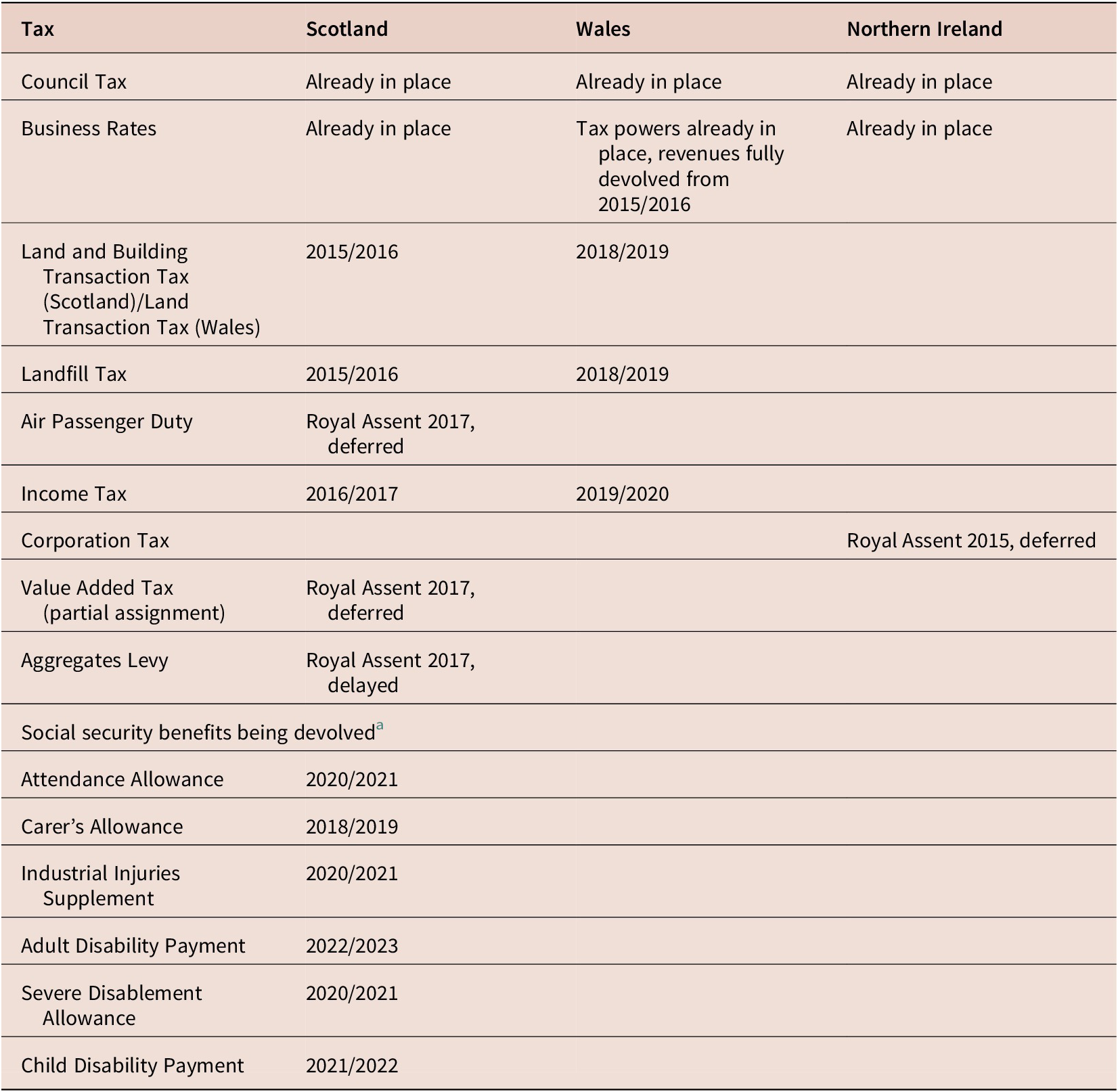

Table 1 brings together the changes to the tax and welfare powers across the DGs in recent years, showing clearly how the changes have clearly been most extensive in Scotland. It also shows that the introduction of the devolved tax and welfare benefits has frequently been delayed following the passing of the enabling legislation. This is largely due to delays in setting up the necessary administrative arrangements, these being particularly complex in relation to welfare benefits. Issues with data (in relation to VAT revenue assignment) and state aid (in relation to aggregates levy and Air Passenger Duty) have also proved problematic.

Table 1. Timetable of the implementation of devolved tax and welfare powers in the devolved governments

Notes. Income tax is partially devolved in Scotland and Wales, although to slightly different models. The model of Corporation Tax legislated for in Northern Ireland was partial, with the Executive having the power to vary the headline rate only. Value Added Tax was due to be partially assigned to Scotland, rather than devolved—offering no scope for policy variation in Scotland. For welfare payments, the dates shown in table 1 are the dates by which the replacement Scottish benefits begin to be rolled out; but the Scottish Government bears the fiscal responsibility for all aspects of the legacy welfare payments in Scotland (including the Disability Living Allowance and Personal Independence Payment) from 2020/2021.

3. Designing the block grant adjustment mechanism

Following devolution of any tax, a deduction needs to be made to the DGs block grant to reflect the transfer of revenues from the UK government to the DG. The ‘block grant adjustment’ (BGA) can be thought of as an estimate of the revenues that the UK government has foregone as a result of transferring a revenue stream to a DG, not just in the first year of devolution but in any subsequent year.

The precise way in which these BGAs are calculated has implications for the way in which fiscal risks associated with a devolved tax are distributed between the DG and UKG. As a result, the way in which they should be calculated has been subject to significant debate (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Eiser and Phillips2016; Fiscal Commission NI, 2021; Ifan et al., Reference Ifan, Poole and Phillips2017). This section outlines these arguments, and the implications of the way in which they have been resolved to date.

3.1. Principles for the design of BGAs

In Scotland’s case, the challenge was to identify a way to calculate and update these BGAs that would simultaneously meet a set of principles for fiscal devolution laid out by the Smith Commission. Most significantly these included:

-

i. No detriment as a result of the decision to devolve: Neither the budget of the DG nor of the rest of the UK should be better or worse off simply because of the devolution of a tax or welfare benefit.

-

ii. Economic responsibility: The DG should capture the full budgetary impacts of its policy decisions, whether they increase or reduce revenue. For example, if income tax is devolved and the DG increases income tax rates, its budget should benefit in full from any resultant increase in revenues. Likewise, if tax rates are reduced for a tax that has been devolved, its budget should be exposed to any consequent fall in revenues.

-

iii. UK economic shocks: That the UK Government should bear the risks of revenue shocks that impact the whole of the UK. If a shock (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) hit the UK as a whole, then the UK Government should manage revenue impacts of this, even in relation to taxes that are devolved.

-

iv. Taxpayer fairness: Changes to taxes in England, for which responsibility has been devolved, should only affect public spending in England. Changes to devolved taxes should only affect public spending in the DG. For example, if income tax is devolved and the UK Government reduces income tax and spending in rUK, then this should not have a negative impact on the DG budget, since the tax cut would not apply within its territory.

These principles, while initially set out for Scotland, have also informed the choice of BGA mechanism in Wales, and informed recent discussions in relation to Northern Ireland. However, the BGA calculations in Wales differ from those in Scotland, reflecting different priorities for how different types of revenue risks are shared between the DG and UKG. Indeed, there are a range of ways to calculate the BGAs that partially satisfy these principles, but as discussed below, none that fully satisfy them, making this complex and seemingly technocratic issue a key source of disagreement between the DGs and UK.

3.2. Operationalising these principles

So how can BGAs be calculated?

The Smith Commission recommended that the calculation of the BGA for each devolved tax should consist of two parts, an initial deduction and an indexation mechanism. The initial deduction is usually the revenue raised (or spent) in the year before the fiscal instrument is devolved. This accords with the first of the Smith Commission’s no detriment principles, ensuring that neither party should be immediately better or worse off as a result of devolution. This part of the BGA is relatively uncontentious, though there is an argument that fairness would also require that the devolved territory and England should be at the same stage of the economic cycle.

The more problematic part is to determine how to index the initial deduction over time, in such a way that the BGA in subsequent years provides a reasonable estimate of the revenues that the UK government has foregone, and simultaneously satisfies the Smith Commission principles. However, a natural place to start is to index the growth of the BGA to some measure of the growth of the equivalent revenues in England.

For example, imagine that in the year before tax devolution, revenues raised from income tax by the UK government in a devolved territory are £20.7bn; this is therefore the initial deduction. The BGA for income tax in the first year of devolution could be calculated simply by applying the growth rate of English tax revenues in the subsequent year to that initial deduction. If English revenues grow at 3 per cent, this 3 per cent growth rate would be applied to the initial deduction, giving a BGA in the second year of approximately £21.3bn.

This simple example, which is known as the ‘Indexed Deduction’ approach, is exemplified in table 2, which illustrates various indexation mechanisms for the case of income tax. The baseline statistics on population and income tax are drawn from England on the one hand, and the sum of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland on the other for 2019/2020. The rightmost column gives assumed constant growth rates for population and revenues which are used to calculate population and revenue totals in years 2 and 10. The simulated outcomes thus correspond to the case of the BGA for an imaginary income tax levied jointly by Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Block grant adjustment indexation mechanisms

Note. DA, Devolved Administration.

The amount, £21.3bn, calculated through the Indexed Deduction would be deducted from the block grant. If revenue growth in the devolved territory keeps pace with that in England, then there would be no net effect on the DG’s ability to fund public services. If it is slower, then the DG’s spending power would be cut, relative to a counterfactual world where devolution had not happened. But if it is faster, the DG’s spending power would be increased. In effect, a BGA calculated this way is making the implicit assumption that, had income tax not been devolved, the UK government’s revenues from that tax in the devolved territories would have grown at the same percentage rate as they have in England. The DG budget captures differential growth in revenues relative to that counterfactual.

In broad terms this simple indexation mechanism, achieves two of the Smith principles:

-

i. It protects the devolved budget from UK-wide shocks that affect tax revenues throughout the UK. If revenues fall by the same proportion right across the UK, the reduction in revenues in the devolved territory will be matched by a fall in the corresponding BGA, insulating the devolved budget from the fall in its own revenues.

-

ii. It ensures economic responsibility: It enables the DG to benefit from the revenue impacts of its own policies. If an increase in tax rates relative to those in England leads to increased revenues, the devolved revenues will exceed the BGA—the DG budget has increased in line with the relative revenue increase. There is no effect on the BGA, which depends only on revenue growth in England.

Whether such an indexation mechanism achieves the taxpayer fairness and no detriment principles is more debatable. This is partly because of the question about whether the growth in total English revenues is a reasonable benchmark on which to grow the BGA—we return to this point subsequently. But it is also because of the way in which growth in English revenues would affect spending in the DGs when we look in more detail at the interaction of the BGA with the Barnett formula.

To see this, think about what happens if the UK government were to increase income tax rates in England after devolution. A tax rate increase would raise revenues in England, which in turn would increase the BGA, implying a larger deduction to the DGs’ block grants. This is not in itself unfair, since taxpayers in the DGs would benefit from the subsequent increase in UKG spending:

-

i. If the UKG increases spending on ‘comparable’ public services in England, then the DGs’ block grants increase automatically through the application of the Barnett formula. The higher BGA offsets the increase in the block grant, reducing the extent to which the DGs benefit from increased spending in England from a tax rise that applies only in England.

-

ii. If UKG spends the additional revenues raised in England on ‘reserved’ matters (like defence, welfare or debt interest) that residents across the entire UK benefit from, the increased BGA ensures that taxpayers in the devolved territories also contribute, despite the tax increase not applying to the DG.

However, whilst the BGAs appear broadly to ensure taxpayer fairness in this context, on closer inspection the increase in BGA does not exactly offset the increase in block grant. This is because of the higher levels of ‘tax effort’ required of the devolved territories because they have significantly lower tax capacity than England.

To see this, let us return to the hypothetical numbers in table 2. Between year 1 and year 2, English revenues have grown by £5.2bn, which is equal to a 3 per cent increase. If the UK government spends the £5.2bn on public services in England, it will generate just under £1bn in additional funding for the DGs via the Barnett formula (this being the DG’s population share of the English spending increase), despite no tax increase applying in those territories. The DGs BGAs will increase, by 3 per cent. But since the DGs raise relatively less revenue from income tax than England, the 3 per cent rise in the BGAs will amount to significantly less in cash terms than £1bn. Specifically, the increase in the BGA will be around £0.6bn, as noted above in the discussion of the Indexed Deduction. In other words, a tax rise that applies only in England will generate additional spending for the DGs, because the Barnett formula works on a ‘per capita share’ basis, whereas the deduction to the block grant works on a ‘percentage change’ basis. In debates with the Scottish government about the design of the BGAs, the UKG argued that the percentage change approach infringed the taxpayer fairness principle.

There is a BGA design that ensures that increases in the Barnett determined block grant are offset in full by increases in the BGA. This method is the ‘levels deduction’ (LD) approach. It increases the BGA by a population share of the increase in English tax revenues. If English revenues increase by £5.2bn generating additional English spending of £5.2bn, the increase to the block grant and increase to the BGA would be symmetric, at just under £1bn. This is because the BGA is calculated by applying the DGs population share to the increase in English tax revenues, in just the same way that the Barnett formula applies the DGs’ population share to the increase in English spending.

But implicitly, given the DGs’ lower tax capacity, the LD approach requires the DGs tax revenues to grow more quickly in percentage terms than England’s, merely for their budgets to be no worse off than they would have been without tax devolution. In table 2, the growth in the BGA under ‘LD’ increases from £20.7bn to £21.7bn, implying a growth rate of 4.6 per cent, compared to the 3 per cent tax revenue growth observed in England. This might be considered an unreasonable baseline; one would not have expected the UKG’s revenues from the devolved territories to grow at this faster rate in the absence of devolution, and it would arguably infringe the ‘no detriment’ principle, since it would imply that the DGs’ budgets would almost certainly be worse off as a result of tax devolution.

Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Eiser and Phillips2016), comparing the properties of these different methods of indexation, conclude that ‘it is impossible to design a BGA system that satisfies the spirit of the “no detriment from the decision to devolve” principle at the same time as fully achieving the “taxpayer fairness” principle: at least while the Barnett Formula remains in place’.

During the 2016 negotiations on Scotland’s fiscal framework, in an attempt to address the argument that expecting DG tax revenues to grow more rapidly than England’s is inherently against the spirit of the Smith principles, the UK government proposed another indexation mechanism known as the ‘comparable method’ (CM). It adapted the LD approach by multiplying the population share of the change in English tax revenues by a factor reflecting the DGs’ tax capacity relative to England’s. Referring to table 2, the CM takes the growth rate of English revenues, £5.2bn, multiplies this by the DGs population share (10.5/57.2), and multiplies this by the ‘comparability factor’ which is a measure of the revenues raised per capita in the DGs relative to per capita revenues in England in year 1 (64.7 per cent in table 2). The BGA calculated through the CM is lower than the BGA calculated under LD, since the former takes account of the DGs lower tax capacity.

Implicitly this approach accepts that some redistribution of English tax revenue growth to the DGs will continue after a tax has been devolved. This was what the UK government proposed in the final negotiations of the Scottish fiscal framework, tacitly accepting that the Taxpayer Fairness principle would not be fully satisfied.

3.3. Which fiscal risks should the DGs be exposed to post-devolution?

But there is another issue that has to be considered in the design of the BGAs, and this relates to the question of which fiscal risks of tax devolution should be borne by the DG, and which by the UKG. Each of the ID, LD and CM approaches index the BGA to some measure of the change in total English revenues. An important determinant of revenue growth is population. If the population of the devolved territories is projected to grow more slowly than the population of England, is it reasonable to index the BGA to changes in total English revenues?

In negotiations around the Scottish fiscal framework, the Scottish government argued that it would not be reasonable to index the BGA to the change in total English revenues—doing so would implicitly require Scottish revenues per capita to grow more quickly than English revenues per capita, merely for the devolved budget to be no worse off. It proposed an indexation mechanism called Indexed Per Capita (IPC). This increases the BGA in line with the percentage increase in English revenues per capita (rather than total English revenues) and Scottish population growth, effectively insulating the Scottish budget from the risk of slower population growth.

In table 2, growth in English revenues per capita is 2 per cent. This 2 per cent growth is applied to DG revenues per capita in year 1 (£1971). The resulting estimate of revenues per capita in year 2 (£2011) is multiplied by DG population (10.5 m) to calculate the BGA of £21.1bn. This method, by protecting the DG budget against the adverse effect of slower population growth on tax revenues, therefore results in smaller BGAs than the ID method.

The UK government was opposed to the IPC method, again on the grounds of the interaction with the Barnett formula on the spending side. The Barnett formula does not account for differences in population growth when calculating changes to block grant funding each year, effectively rewarding the DGs with a bigger increase in funding per capita than England when their populations are growing more slowly.Footnote 3 From this perspective, there is no rationale to insulate the Scottish budget from the effect of slower population growth on the revenue side.

To summarise, the IPC method removes population risk from the BGA, and controls for the DGs lower initial tax capacity. The LD approach does not control for either relative population growth or lower initial tax capacity, resulting in much more rapid BGA growth and hence relative shrinkage in the DG budgets. The CM and ID methods both protect the DG budgets from their lower initial tax capacity, but offer partial or no protection against relative population growth. The larger BGA associated with the CM is favoured more by UKG, while the Scottish Government favours the IPC, with both claiming that their chosen method is closer to the Smith Commission principle of taxpayer fairness.

In the Scottish case, the UK and Scottish governments agreed to adopt the IPC approach to index Scotland’s BGAs, albeit with some convoluted wording in order to keep the CM approach on the table over the longer term (Scottish Government, 2016). It was intended that the system would be reviewed after 5 years, that is, in 2021. This review process is now in train, albeit somewhat later than intended.

The approach agreed to indexing the BGAs in Wales differs from that used in Scotland in two ways. The Welsh BGA is calculated using a variant of the CM approach that protects the Welsh budget from fiscal risks arising from it having a different distribution of income taxpayers relative to England (Welsh Government, 2016).

Protection against the risks associated with having a different distribution of taxpayers is afforded through calculating separate income tax BGAs for each band of income tax. Such protection is important because Wales has proportionately many fewer higher and additional rate taxpayers than England. This means that if revenues from these top tax bands grow more quickly than those from the basic rate, then even if growth in Welsh revenues from both these top tax bands and the basic rate matches revenue growth in England from those bands, Wales would lose out. That is because if a single BGA was used for all of income tax, this would grow more rapidly than Welsh revenues, given that overall English income tax revenues would be much more influenced by the high revenue growth from the top tax rates. Such risks are particularly likely to arise if tax policy changes introduced at UK level make income tax more progressive, that is raising tax rates on high incomes and/or cutting tax rates on low incomes. This has indeed been the case in recent years, given real terms increases in the tax-free personal allowance but a cash freeze in the additional rate threshold.

The price of the Welsh government securing this ‘by band’ methodology was that it agreed to the use of the CM approach rather than the IPC approach. So whilst the Welsh budget is protected from risks associated with the distribution of its income tax base, it is not protected against the risk of a relatively slower growing population in future years.

Since there has been no recent tax devolution to Northern Ireland, the BGA question has not yet explicitly raised its head there. However, one of the reasons why devolution of Corporation Tax to Northern Ireland was delayed and ultimately not implemented related to debates about the appropriate BGA mechanisms, and in particular which fiscal risks should be borne by each government. The UKG argued that the Northern Irish budget should bear the risk that a lower Corporation Tax rate might lead to the shifting of profits from Great Britain—with some form of compensating mechanism in place. How this might work in practice was never agreed.

3.4. Tax revenue performance in practice

Even if there were no disagreements of the appropriate measure of the change in revenues in England with which to index the BGAs, if DG revenues under- or over-perform relative to this benchmark, the DGs’ budget will be higher or lower than in the absence of devolution even in the absence of policy change. The risks of tax devolution are real and have been realised in Scotland’s case. Income tax policy changes introduced by the Scottish government in 2018/2019 are estimated to have raised around £240 million in additional revenues compared to what would have been raised had UK income tax rates and bands been implemented.Footnote 4 However, the net benefit of income tax devolution to the Scottish budget—reflected in the difference between revenues and the income tax BGA—in 2018/2019 was only £119 m. Around half of the anticipated revenue impact of the policy changes was offset by relatively slower growth in the Scottish income tax base compared to the equivalent tax base in rUK. A similar story emerges in 2019/2020—the Scottish budget is only around £148 m better off as a result of income tax devolution, despite tax policy changes that would in theory raise Scottish revenues by over £400 m compared to what would be raised under rUK policy. This outcome is because the income tax base has grown more quickly in rUK than in Scotland. Without income tax devolution, Scotland would have received a population share of this faster growth in rUK tax revenues via the Barnett Formula. But following tax devolution, growth in rUK income tax revenues are only partially pooled and shared across the UK.

3.5. Summary

Although they are central elements of the fiscal frameworks, the issues around the selection of BGAs are complex. One clear lesson from table 2 is that, even with a somewhat artificial choice of levels and growth rates, choice of indexation method makes a significant difference to BGAs and therefore in the ability of the DGs to spend, particularly in the longer run. Recall also that their effects are purely redistributive since losses incurred by the DGs become gains for England. BGA mechanisms also differ between the DGs, implying different agreements around the distribution of risk and reducing the incentive for the DGs to act jointly in negotiations with UKG. And unfortunately, the complexity of the choice between them undermines public debate on the merits of the different indexation mechanisms and the consequent incentives to improve economic performance.

The fiscal frameworks for Scotland and Wales also set out new arrangements for DG borrowing and the use of cash ‘reserves’ in order to mitigate the impacts of forecast errors on their budgets. The scope of these budget management tools is quite constrained, particularly in the Scottish government’s case (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Eiser and Phillips2021). The Scottish and Welsh governments also gained some ability to borrow to fund capital spending. McCann (Reference McCann2021) points out that borrowing limits for sub-national governments in the UK are substantially lower relative to GDP than those in other developed countries. This issue is also discussed by Armstrong and Ebell (Reference Armstrong and Ebell2014).

The changes to the Scottish and Welsh fiscal frameworks have been significant, increasing the DGs’ accountability for taxation and economic performance. Negotiations around the supporting arrangements, in relation to BGAs and borrowing powers, have been somewhat contentious, and created tensions around the interpretation of the so-called ‘principles’ of the Smith Commission, which in reality leave a lot to interpretation.

However, two major subsequent shocks—Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic—have provided a substantial stress test of the new arrangements, both because of their impact on levels of public spending and taxation, but also because of their influence on the balance between reserved and devolved competencies.

4. Brexit

Brexit raised important political and economic questions for the DGs as well as for UKG. This section focuses on the economic issues and how they interact with the fiscal frameworks. We argue that whereas the changes to the fiscal framework extended the economic powers and responsibilities of the DGs, Brexit has lessened the clarity around the division of competences between the UKG and the DGs and has worsened relationships between the DGs and UKG. This has occurred in several ways. The way in which EU Structural Funds have been repatriated to the UK reduces the policy autonomy of the DGs, relative to their involvement in designing and implementing EU schemes. The UKG’s decision to exclude the DGs from any role in negotiating post-Brexit trade deals has created inter-governmental tensions, given the DGs’ role in implementing the outcomes of trade agreements. Changes to the UK’s regulatory framework and State Aid regime post-Brexit both have the potential to effectively limit the policy freedom that the DGs may have expected to have post-Brexit, and reduced opportunities for scrutiny and engagement by the DGs relative to EU policymaking processes. In this section, we provide a brief overview of these issues.

First, a major post-Brexit issue for the DGs was the replacement of the European Structural Funds. Although funding was channelled through the EU, these funds were among the main instruments of regional policy within the UK. In the 2014–2020 budget round, €16.3 billion from these funds was allocated to the UK (Brien Reference Brien2021), of which €11 billion was aimed at general economic development, and €5.3 billion for rural and coastal development through the Common Agriculture and Fisheries policies. Their geographical distribution was determined by a combination of EU eligibility rules which were based largely on local levels of GDP per head, and UK government decisions on other needs indicators (Davenport, North and Phillips, Reference Davenport, North and Phillips2020). This made them unusual for the UK in the sense that they were explicitly based on indicators of need whereas the Barnett Formula—the main mechanism for allocating funding to the DGs—is based on historic funding levels. Wales was the main beneficiary with the 2014–2020 allocation being worth around £800 per head per annum (Bell, Reference Bell2017). The DGs were responsible for allocating Structural Funds within their territories, and had a degree of policy autonomy to determine the funding priorities, within a general EU framework.

The 2017 Conservative Manifesto committed to the creation of a United Kingdom Shared Prosperity Fund (SPF)—‘to reduce inequalities between communities across our four nations’. It would also ‘respect the devolution settlements across our four nations’. However, there was still no clarity on the design of the replacement by the end of 2021, though the 2021 Spending Review committed to a spend of around £1.5bn per year. As a precursor to the SPF, the UKG introduced the Community Renewal Fund in 2020/2021. The fund was administered by MHCLG, which invited applications from local authorities across the UK. The DGs had no role in the application or the awards. Their contention is thus that the taking back of control of regional development policy from the EU to Westminster has weakened their own scope to determine economic development policy.

Related to this, a contentious element of the Internal Market Act that was passed by the UK parliament to facilitate regulatory changes required post-Brexit is the power it gives the UKG to spend on ‘economic development, providing infrastructure, supporting cultural and sporting activities and supporting education and training activities and exchanges’. This is an enabling mechanism which could be used by UKG to distribute the SPF across all of the nations without involving the DGs. These new UKG spending powers overlap with competences previously thought to be the preserve of the DGs because they were not listed as ‘reserved powers’ under the various Acts that established the DGs. The Internal Market Act thus provides UKG with powers to compete or co-operate with the DGs in providing economic development assistance, infrastructure and so forth. Yet, the fiscal frameworks have developed independently of this important change in UK legislation. Brexit precipitated the requirement to replace EU regulation, but the form of the associated legislation is not consistent with the design of the fiscal frameworks and pre-existing devolution legislation.

It is worth noting however, that even in some relatively decentralised federal countries like the United States, the federal government has and utilises the power to direct resources to spending on areas such as infrastructure, economic development and skills—so it is perhaps unsurprising that the government of a formally unitary state also desires such powers. Of course, beyond the political and constitutional issues posed by the fact that this is inconsistent with prior interpretations of the devolution settlement, it could also lead to inefficient overlaps or gaps if the UKG and DGs do not properly coordinate policies.

Second, the DGs have played no part in developing negotiating mandates, negotiating or ratifying post-Brexit deals, and have been given limited sight of these deals during their development (Eiser et al., Reference Eiser, McEwen and Roy2021). Many federal nations at least consult their province or state governments when negotiating trade deals especially where their specific interests are at stake. Fafard and Leblond (Reference Fafard and Leblond2013) make the case that Canadian provinces, although consulted on the Canadian-EU trade agreement (CETA), did not have a veto on the trade deal organised between the blocs. Hübner et al. (Reference Hübner, Deman and Balik2017) take an opposing view of CETA, arguing that so many actors are now involved with such deals that their ratification is increasingly difficult. UKG has avoided this problem by not involving the DGs in any way in the trade deals agreed during 2021. Thus, even though, for example, the share of agriculture in GDP is higher in both Wales and Scotland than in England, the UKG did not consult the respective DGs during trade negotiations with Australia and New Zealand, both major agricultural exporters.

In a formal sense, this is little change from the situation pre-Brexit: UK DGs did not have a formal say in EU trade deals (unlike DGs in some other countries). However, the process for agreeing and ratifying trade-deals in the EU, including the agreement of each member state, arguably gave more opportunity for scrutiny and engagement more generally, including by the DGs.

Third, Brexit also triggered regulatory changes that have affected the relationships between DGs and UKG. The UK Internal Market Act embeds the principle of ‘mutual recognition’—that any good that is compliant with product standards in one of the UK nations can be sold in any other nation. This disincentivises DGs from legislating to raise local product standards since these might be undercut by similar products from elsewhere in the UK. Partially offsetting the effects of imposing mutual recognition are the ‘common framework agreements’ that are being negotiated between the four nations to manage differences in areas of EU law that have been returned to the UK.

Lastly, a particular sticking point in the Brexit negotiations between the UK and EU was the treatment of state aid, which was previously overseen by the EU. Disputes were resolved by the European Court of Justice (ECJ).Footnote 5 Brexit required a change to these arrangements. The UKG now uses the terminology ‘Subsidy Control’ to cover these issues. During the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) negotiations the EU wanted to ensure a ‘level playing field’, so that its companies were not undercut by state-subsidised competition from UK enterprises. The UKG has introduced the Subsidy Control Bill to comply with EU requirements. But its design differs considerably from the EU State Aid regime.

The Subsidy Control Bill proposes six principles that any granting of a subsidy by a public body to a ‘beneficiary’ (usually a firm) should respect. These principles are broad brush—they allow considerable room for interpretation and therefore for dispute. The UK Secretary of State will introduce secondary legislation to clarify the kinds of scheme that will be considered allowable within the principles, but this gives considerable powers to UKG to introduce schemes opposed by the DG, or block schemes proposed by them. Peretz (Reference Peretz2021) argues that:

The Secretary of State’s extensive regulation-making powers, and his power to make “streamlined subsidy schemes” without any review by the CMA [Competition and Markets Authority], are all exercised without any requirement to consult, let alone obtain the agreement of, the devolved administrations, even though those powers may have considerable impact on their powers and policies.

Not surprisingly, both the Scottish and Welsh governments have expressed significant reservations about this Bill.

Brexit has thus had two sorts of impacts on the policy space available to the DGs. In relation to the repatriation of Structural Funds, there is a real concern that Brexit may have reduced the ability of the DGs to design and implement economic development policy in their own territories. In relation to trade, market regulation and state aid, the DGs do not necessarily have less formal ability to influence these institutions than previously, EU regulation having been replaced by UKG determination. But the UKG’s insistence that the DGs should have no role in developing policy in these areas, despite the DGs role in implementing trade agreements and the scope of state aid and market regulation frameworks to constrain the DGs policy space—has further weakened relationships between the UKG and DGs.

The UKG approach might be described as ‘muscular unionism’ or perhaps ‘competitive devolution’. But it seems that the DGs now feel threatened by the extension of UKG spending into competences previously thought to be their sole preserve.

These developments also cast doubt on the design of the fiscal framework since the operation of the Barnett Formula is based on the annual ‘Statement of Funding Policy’, HM Treasury (2021a) which specifies exactly the proportion of each spending programme that will attract Barnett ‘consequentials’. New powers for UKG to spend directly in the territories of the DGs undermines the clarity of these arrangements.

More broadly, Brexit has changed the case for, or the feasibility of, the devolution of particular policy competencies. Devolution of VAT to Scotland, rather than assignment of VAT revenues as had previously been proposed, is now legally permissible, which was not the case whilst the UK remained in the EU, a point that the Scottish Government has made repeatedly in recent years. Devolution of excise duties to Northern Ireland is now not only legally possible, but hypothetically much more administratively feasible given the presence of the Northern Ireland protocol—a fact that has influenced the deliberations of the NI Fiscal Commission. Brexit also, in the Scottish Government’s view, strengthens the case for migration policy to be devolved. Devolving control over migration is strongly advocated by the Scottish Government (2020) which is the only part of the UK where population is projected to fall (Office for National Statistics, 2022). Brexit may thus in theory provide some opportunities for devolution that did not previously exist. To date however, Brexit has tended to result in a tendency towards greater centralisation rather than devolution of power.

5. The COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic drove a quite different and more immediate set of pressures on the fiscal frameworks. These came about because of the huge within-year spending pressures caused by the pandemic. In 2020/2021, UK public spending increased by £231bn (26.2 per cent) compared with 2019/2020.Footnote 6 The UKG’s response to the pandemic in relation to working age social security, the furlough scheme, and income support to the self-employed, applied across all parts of the UK. The DGs are responsible for designing and implementing the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic in their respective territories, and significant elements of the economic response, including funding support to businesses, local authorities and transport providers. By design, the DG fiscal frameworks provide no scope for the DGs to borrow to address unforeseen shocks—the assumption being that the UKG bears responsibility for the responsibility for fiscal shocks that are common to the UK. The DGs were thus reliant on increased grant from the UK government to implement their responses.

The pandemic was thus a serious stress test of the devolved fiscal frameworks. At the outset, there were legitimate reasons to be concerned about how the devolved fiscal frameworks might cope. Primarily these concerns related to the possibility that the pandemic might have very uneven, or asymmetric, fiscal effects across the UK nations, which the devolved funding frameworks, with their implicit emphasis on equivalence of fiscal treatment relative to England, might have been ill-equipped to deal with.

But these also included risks around delays and uncertainties to the confirmation of DG funding, which may have created difficulties for the DGs in planning and implementing a timely response. Normally, it is only when the UKG announces new spending on comparable public services in England that a consequential change in the block grants of the DGs is triggered via the Barnett formula. In the early stages of the pandemic, the high frequency of new policy and spending announcements from UKG created planning challenges for DGs who were constantly in the position of trying to second guess what policies the UKG might announce for England, and how much spending would be associated with these. Only when the UKG confirmed what funding was associated with its own policies could the DGs confirm the design of their own schemes.

In the end, Bell et al. (Reference Bell, Eiser and Phillips2021) conclude that the devolved fiscal frameworks coped reasonably well with the pandemic shock, for three reasons.

-

i. First was the fact that the health and economic impact of the shock was felt fairly symmetrically across the UK nations. This meant that the notion of per capita equivalence in funding changes at the heart of the devolved fiscal frameworks was not in principle problematic or resulted in obvious funding inequities. The oft-maligned BGAs worked as intended to protect the DG budgets from revenue falls during the pandemic, since these revenue falls were experienced UK-wide.

-

ii. Second, the sheer scale of funding increases by the UKG in England generated such substantial increases in the DGs block grants (table 3) that the DGs were never seriously in a position where they could argue that they had insufficient funding to implement their policy aspirations.

-

iii. Third, the UK government made one important ad hoc change to the devolved funding arrangements in July 2020. This was the move to so-called funding guarantees. These were minimum guaranteed increases in the DGs’ block grants for the 2020/2021 financial year, in advance of the confirmation of specific policies by the UKG in England. The funding guarantees meant that the DGs could make financial plans in the knowledge that they would receive at least these minimum grant uplifts, even if the UK government’s eventual spending would have implied a lower allocation under the traditional Barnett formula approach.

Table 3. Allocations of core and COVID-19 related resource grant to the devolved authorities 2020–2022

Note. The DGs allocation of COVID funding was not ring-fenced from the DGs perspective, although it was accounted for separately for budgeting purposes.

A second ad hoc change made to the fiscal arrangements was the relaxation of reserve drawdown limits. Whilst this was not as significant an ad hoc change as the introduction of funding guarantees, it was important in enabling the DGs to transfer additional funding, received late in the 20/21 financial year, into the following financial year—again allowing a more strategic approach to be taken by the DGs.

The devolved fiscal frameworks therefore largely passed the stress test of the pandemic, even though this did require some ad hoc muddling through by the UKG. Inter-governmental tensions around funding were therefore not as prevalent as one might have expected, although more substantive disagreements in relation to the furlough scheme were only narrowly avoided. The issue here related to uncertainties around the extent to which the furlough scheme (CJRS) could be made available within a devolved nation if a DG felt the need to apply tighter coronavirus restrictions than prevailed in England. The resulting inter-governmental tensions around this issue in autumn 2020 may have marginally influenced the timing of particular restrictions being applied in Scotland and Wales. But major crisis around this issue was averted by the UK government’s subsequent decision to extend the furlough scheme across the UK when England entered lockdown again in November 2020.

We can only wonder how the devolved fiscal frameworks might have coped had the effects of the pandemic been more obviously asymmetric across the UK nations. Had the effects been less symmetric, population-based increases in funding under the Barnett Formula would have been less successful. One or more of the DGs could have been unable to mount an adequate policy response to the pandemic.

Accommodating differential fiscal responses to asymmetric shocks would be difficult, especially in the short run, because the information used to trigger such a response would have to be accepted as accurate by the UKG and relevant DGs. Unless all parties agree on the existence and scale of the asymmetric shock, accurately tailored fiscal responses are unlikely. Prior agreement on the information necessary to trigger a fiscal response targeted on one of the DGs might aid agreement but is unlikely unless the nature of the shock can be accurately predicted. Less restrictive borrowing limits would enable the DGs to take their own view on the severity of the challenge they face, giving more time for analysis of the nature of the shock.

6. Conclusion

The past decade has resulted in very significant alterations to the UK sub-national fiscal architecture. Scotland in particular, and Wales to a lesser extent, have taken control over important tax and welfare policy instruments. The changes have been driven to some extent by the reaction of unionist politicians to perceived threats of secession, principally from Scotland. But they are also motivated by well-founded aspirations to raise the fiscal responsibility of the devolved parliaments, and hence to enhance the accountability of those parliaments to their electorates.

The extent of the changes and their implications are not well understood. This is largely due to their complexity. The BGAs which offset the new tax revenues devolved to the DGs are complex mechanisms which redistribute some risks based on principles derived from the Smith Commission that are difficult to reconcile. These risks are much less extensive than those that would be associated with ‘full fiscal autonomy’: the DGs are insulated from differences in their fiscal capacities at the point of devolution, and from common shocks affecting revenue and spending across the UK as a whole post-devolution. Nevertheless, differences over the design of the BGAs and therefore over the allocation of risk have done little to enhance inter-governmental relations.

Those relations have then been subject to two unforeseen stress tests in the shape of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Brexit stress test has further weakened inter-governmental relations due to disputes between the DGs and the UKG over the latter’s decisions on the repatriation of powers previously exercised by the EU. These include lack of consultation over trade agreements, the Internal Market Act, the Subsidy Control Bill, the delay to and design principles of the UK SPF (the replacement of EU Structural Funding), and disputes over migration policy. These measures have led to the DGs feeling side-lined with their powers being circumscribed by the Internal Market Act and the Subsidy Control Bill. As a result, there is a view that there is less clarity over the division of competences between them and UKG than there was a decade ago. Whether described as ‘muscular unionism’ or ‘competitive devolution’, Brexit is leading to further strains on inter-governmental relations.

The fiscal frameworks have arguably coped more ably with the COVID-19 stress test, through a combination of one important ad hoc change to the normal funding rules, and an element of luck in the form of a pandemic whose impacts were evenly felt across the UK nations. The scale of the UKG’s funding response, and its willingness to flex normal devolved funding arrangements, enabled all parts of the UK to manage their public health response to the pandemic without encountering significantly different fiscal restraints.

Nevertheless, this is an uncomfortable time for the future of the union, with inter-governmental relations at a low ebb. Fiscal interactions between the UKG and the DGs have played a central role in recent conflicts. DG frustrations with the lack of progress and confused messaging in relation to the UK SPF are but one example of such tensions. Such problems were recognised in a recent review of inter-governmental relations during Brexit (House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, 2018). It argued that:

There is a growing consensus that the current inter-governmental relations mechanisms in the UK are not fit for purpose (P5).

A recent review of inter-governmental relations undertaken jointly by the UKG and the devolved administrations has suggested a solution to these issues (Cabinet Office, 2022). It is proposing an entirely new approach to aspects of inter-governmental relations that concern finance and the economy. The ‘Finance Interministerial Standing Committee’ will be set up to deal with these issues and will meet each quarter. Its aim is to consider the impact of macroeconomic and fiscal matters affecting the UK. However, its disputes mechanism is quite restrictive and limited to apparent breaches of the principles of the Statement of Funding Policy. This development seems like an attempt to reset UK inter-governmental relations. But, with a narrowly defined disputes mechanism for financial issues, as McEwen (Reference McEwen2022) argues ‘the proof will be in the practice’. Improved relations may guide the fiscal frameworks towards a more stable future. In the case of Scotland, continued sparring between governments may be one of the pretexts for increased pressure to hold another independence referendum.

This article has attempted to explain the complex nature of the UK fiscal framework, how it developed over the last decade, and continues to develop. It has also considered the effects of both Brexit and the pandemic on the stability of fiscal and economic relationships between UKG and the DGs, arguing that they have played a part in the worsening of inter-governmental relations in recent years. Whether the new architecture proposed for inter-governmental relations will restrain the centrifugal forces affecting the UK union remains to be seen.