There is a paucity of Palaeolithic art in the southern Levant prior to 15 000 years ago. The Natufian culture (15 000–11 500 BP; Grosman Reference Grosman, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013) marks a threshold in the magnitude and diversity of artistic manifestations (Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef, Conkey, Soffer, Stratmann and Jablonski1997). Nevertheless, depictions of the human form remain rare—only a few representations of the human face have been reported to date. This article presents a 12 000-year-old example unearthed at the Late Natufian site of Nahal Ein Gev II (NEGII), just east of the Sea of Galilee, Israel (Figure 1). The object provides a glimpse into Natufian conventions of human representation, and opens a rare opportunity for deeper understanding of the Natufian symbolic system.

Figure 1. The human face carved on a limestone pebble from Nahal Ein Gev II (Late Natufian) (photograph by Gabi Laron).

The human face carved on a pebble and its parallels

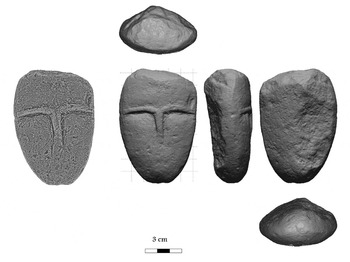

The NEGII face is carved from a limestone pebble measuring 90 × 60mm. Minimalistic manipulation of the pebble's surface creates a simple but realistic human expression. The artist used the natural form of the pebble to represent the outline of a human head, and slightly modified the stone's perimeter with a flat band to shape the contours of the face (Figure 2a). The main modification engraved on the front of the pebble consists of a T-shaped linear relief that emphasises an eyebrow ridge and nose; two low arcs that meet at the centre of the pebble form the eyebrow ridge and then turn downward to depict a straight, elongated nose.

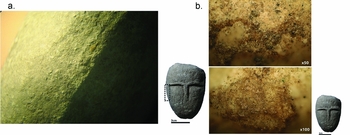

Figure 2. a) The flattened band around the edge of the pebble; b, top) stereomicroscope observation at 6× magnification; b, bottom) micropolish associated with the dark and shiny areas observed at high magnification. The micropolish is discontinuous, bright and smooth (the magnified area is marked by the rectangle).

By skilful play with line depth and curvature, the artist has achieved a soft depiction of the cheeks and deep, shaded eye sockets (Figure 3). The artistic qualities of the representation are schematic, but they present a realistic and uniquely expressive human face. The back of the pebble is not carved but is lightly modified at the edges. Microscopic analysis shows a few small, smooth and shiny areas that may have been created by gentle polishing of the surface with a soft material such as skin or fabric, or by contact with soft fabric wrappings (Dubreuil Reference Dubreuil2004; Dubreuil et al. Reference Dubreuil, Savage, Delgado, de la Torre, Plisson, Stephenson, Marreiros, Gibaja and Bicho2015; Figure 2b). No residues or signs of colouration adhere to the stone's surface.

Figure 3. 3D scan of the Nahal Ein Gev II stone face documented in Artifact3-D (Computerized Archaeology Laboratory, Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University; Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Karasik, Harush and Smilansky2014). The grey rendering provides a clear visualisation of the geometry of the object, specifically the lines that depict the face. Note the carved lines that deviate from the lower part of the nose to the left.

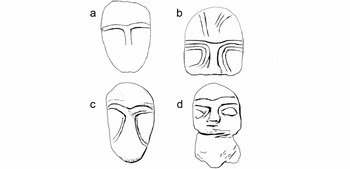

A small yet diverse group of anthropomorphic human representations have been recovered from Natufian contexts (e.g. Perrot Reference Perrot1966: figs 21.17 & 23.1; Weinstein-Evron Reference Weinstein-Evron1998: fig. 58.2–3). To date, only three pebbles depict the human face: one from el-Wad Cave (Garrod & Bate Reference Garrod and Bate1937: pl. XIII.4) and two from Eynan (Perrot Reference Perrot1966: fig. 23.2–3) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of human faces on pebbles: a) Nahal Ein Gev II; b–c) Eynan (after Perrot Reference Perrot1966); and d) el-Wad (after Garrod & Bates Reference Garrod and Bate1937) (not to scale, drawn by Hadas Goldgeier).

Collectively, these stone faces share an artistic quality—the eyebrow ridge and nose are drawn in linear relief, resulting in a schematic depiction. The stone face from NEGII is most similar to one of the two examples from Eynan (Figure 4c); both are minimalistic—the image is created by only a few lines. Yet the stone face from NEGII is unique in its more precise representation of human expression.

Nahal Ein Gev II

The NEGII site is located on a flat alluvial terrace on the right bank of Nahal (wadi) Ein Gev. The site dates to the very end of the Natufian period (12 550–12 000 cal BP). Abundant architecture, built features and thick archaeological deposits suggest that it represents a large, intensive village that was inhabited for several centuries (Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Munro, Abadi, Boaretto, Shaham, Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef2016).

The excavations and test pits at NEGII reveal an extensive habitation area covering around 1200m2. Excavations have concentrated on the naturally sloping eastern edge of the site, which was partially eroded by a stream. The deep stratigraphy (2.5–3m deep) contains only a homogeneous Natufian unit that can be divided into multiple construction sub-phases. Dense material remains, particularly lithic artefacts, are distributed throughout the layers. Lithic attributes verify the chronological assignment of the site to the end of the Late Natufian.

On the first day of the 2016 excavation season, a path was constructed down the eroded east slope of the site to contain foot traffic and to protect the loose, sloping, Natufian deposits. During construction, the carved-stone human face was discovered on the surface of the exposed Natufian deposits (Figure 5), in excavation square RG63. Although we are certain that it was embedded in Late Natufian deposits, the square remains unexcavated, and thus we do not yet know its specific archaeological context (e.g. structure or feature).

Figure 5. Area B at Nahal Ein Gev II in 2016, a view to the south-east. The location of the findspot is indicated by the red arrow (photograph by Dana Shaham).

Discussion

The human face carved on a pebble from NEGII shows a schematic depiction that lacks detail. This quality also characterises other Natufian human-face representations, and thus might reflect a Natufian cultural convention. Schematisations of this kind generalise the human face rather than offering an individual ‘portrait’. Nevertheless, unlike other Natufian carved-pebble faces, the cheeks of the example from NEGII are softly moulded, while the eye sockets are emphasised using expressive shading: qualities that create a lively expression.

The three other carved-stone human faces are Early Natufian in date, whereas NEGII is dated to the end of the Late Natufian. Consequently, the NEGII example may reflect either a virtuosic artist or part of a diachronic trend that bridges the Early Natufian and Early Neolithic artistic traditions. Other aspects of the NEGII art assemblage (Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Munro, Abadi, Boaretto, Shaham, Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef2016) exhibit a style that is closely related to the Early Neolithic world, although it reveals deep roots in the Early Natufian tradition. Importantly, these changes in art accompany other documented changes in subsistence, settlement and technology that are already underway by the very end of the Natufian period.

Acknowledgements

We thank the students of the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University and other Israeli and international institutions for participating in fieldwork at NEGII. Special thanks go to Keren Nebenhous, who found the object. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (1415/14 to L.G.) and the National Science Foundation (BCS-1318381 to N.D.M.); Israel Antiquities Authority permit G-77/2016 (L.G.); Nature Parks Authority permit to excavate at Ein-Gev 24/16 א (L.G.).