I

No subject affecteth us with more delight than history, imprinting a thousand forms upon our imaginations from the circumstances of place, person, time, matter, manner, and the like. And what can be more profitable, saith an ancient historian, than sitting on the stage of human life, to be made wise by their example who have trod the path of error and danger before us …Footnote 1

In this article I will consider the relationship between the human body as a material object and visual signifier, and the complex philosophical concepts it is sometimes called upon to articulate in theatrical and cinematic contexts. In particular, I will outline an understanding of the body as a disruptive site that has problematized the creation of theatrical and cinematic meaning, as well as the conveyance of performative intertextual authority, in recent performances of Shakespearian drama. My case study is Lavinia in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, with a focus on the ways in which Lavinia’s body has distracted film and theatre directors (and audiences) as a result of the immediacy of the physical torment it undergoes, and how, ironically, it has turned them away from the potentially feminist performative, literary and historical intertextuality it is intended to provide. My argument centres on the fact that Lavinia is not meant at all times to be a representation of individual human subjectivity; rather, like many Renaissance characters, she is frequently a dramaturgical device incorporated into the play in order to provide a way into intertextual frames of reference essential to more meaningful understandings of Shakespeare’s drama. Unfortunately, approaches to the presentation of dramatic character that incorporate notions of performative intertextuality, abstraction and character-as-metaphor are very much out of fashion in contemporary theatrical and cinematic practice.

Titus is a challenging play, a slippery rhetorical text upon which it is very difficult to get a sustained philosophical grip. Perhaps this is why so many critics and theatre directors have misunderstood it over the years, and have detected in it the kind of cliché of classical allusions that Shakespeare himself ridicules in comic terms in later plays. Some have scorned its supposedly amateurish formal conception.Footnote 2 As Bate, Waith, Palmer, James and Rowe have shown in a new critical tradition beginning in the 1950s, however, such responses are just plain wrong-headed. Shakespeare’s use of contrasting literary and historical sources is not the mess that unsympathetic critics have claimed it to be. Rather, a playfully eclectic use of classical intertextuality is what gives Titus its philosophical cohesiveness: like a bicycle wheel, the play is held together by the creative tension of significant forces pulling in different directions. In response to T. J. B. Spencer’s 1957 accusation that ‘the author seems anxious not to get it all right, but to get it all in’,Footnote 3 Jonathan Bate has famously replied: ‘quite so, but this is exactly the point’.Footnote 4 Recent philological readings of Titus have accordingly outlined the ways in which Shakespeare uses Livy’s Histories and Ovid’s Fasti (for Tarquin and Lucretia) to speak about the legitimacy of absolutist monarchy and the move towards republicanism. Equally insightful have been readings that pick up on Shakespeare’s choice of the wicked emperor Saturninus from Suetonius and Tacitus – in whose work the tyrant is contrasted with wholesome, pastoral Germans who stand as code in the Renaissance imaginary for Protestant Reformation. Even the fact that Shakespeare chose Virgil’s Lavinia, the mother of early Rome, as the mutilated daughter of that empire in decline has been used to demonstrate that ‘the founding acts of Empire turn out to contain the seeds of its destruction’.Footnote 5

Of the many horrendous sights in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, Lavinia’s mutilated body stands apart as one of the play’s most powerful testaments to the barbarity of both Roman and Gothic cultures. Despite the acts of sensationalist violence that are visited upon it, this body somehow persists; its ‘lopped and hewed’ trunk remains unremittingly on stage as an awkward and yet perplexingly beautiful signifier of the thorny relationship between human bodies and the concepts they are used to articulate in performance. The text of Titus Andronicus asks the Lavinia actor to embrace oxymoron, to use his (or her) body as a ‘map of woe, that … dost talk in signs’ (3.2.12), a figurative and emblematic trope pointing to the human cost of the play’s central themes: loyalty, revenge, filial duty, the lust for power and dominion. Lavinia’s stage and screen body accordingly derives power from the fact that it is a channel through which much of the play’s intertextuality is mediated. Much of Lavinia’s performative force accordingly comes from the fact that she exists in a symbolic theatre and is presented through a significant distancing device: theatrical transvestism. Transvestite representations of femininity, from the stages of ancient Athens to those of early modern England, derived much of their potency from the fact that audiences did not consider them to be real in all respects, but rather that they could also be understood as rhetorical investigations of the nature of human (both male and female) subjectivity.Footnote 6 Lavinia’s existence on stage, post-rape and dismemberment, is a biological impossibility that indicates she has more in common with the figurative emblems of Ripa’s Iconologia than she does any actual human subject. Her dramatic power and performative agency are accordingly rooted in the ways in which she both evokes and resonates against a variety of classical exemplars.

In what follows I consider the fundamental difficulty that seems to exist in attaining a similar theatrical and cinematic reception and interpretation history for Titus as that which has been achieved in critical terms. To do this, I shall ask two questions: (1) why does it seem that so few modern directors have been capable of connecting all of the pieces of Shakespeare’s complex intertextual theatrical puzzle?; and (2) why do a significant number of directors appear to be more interested in the physical actions undertaken by and upon performers (and particularly female performers) than in the rhetorical language that the same dramatic constructs, or those around them, simultaneously articulate vocally to represent the play’s philosophical arguments?

Which brings me to performance.

II

The first account of Titus is a production in the home of Sir John Harrington on 1 January 1596. Jacques Petit, the French tutor to Harrington’s household, offers a glimpse of the apparent tension he felt between the performative elements of Titus and the play’s more sophisticated literary, philosophical and political intentions.Footnote 7 Following a performance by an unnamed London company (presumably the Lord Chamberlain’s Men), Petit observed, ‘on a aussi joué la tragédie de Titus Andronicus mais la monster a plus valu que le sujet’.Footnote 8 His opinion is that the play’s spectacle (la monster) was of greater import than its subject matter (le sujet). A second early modern response makes the point even more forcefully. In an account of Titus that appeared in a collection of plays translated into German by Frederick Menius in the 1620s, purporting to be a record of plays acted by the English in Germany during the period,Footnote 9 we see a version of Titus stripped entirely of its intertextual relevance. The cast is cut to twelve speaking parts and two silent extras; all of the play’s classical allusions are removed (even to the point of providing just a bucket of sand and a stick for Lavinia – no copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses exists here for her to draw the parallels to Philomela that are so important to Shakespeare’s text). Jonathan Bate has observed of this written German account of a touring English player version that a ‘“lower” audience than Shakespeare is implied, one which requires a strong concentration on spectacle and action rather than ornate rhetoric’.Footnote 10 The reasons for the absence of any desire to prompt understanding of the play’s highly developed intertextuality in this account would appear obvious: profound understanding of Shakespeare’s Titus can only be achieved by those who: (1) have seen its contemporary theatrical intertexts staged (and thereby derive metatheatrical pleasure in Shakespeare’s exploitation of contemporaneous London theatregrams);Footnote 11 and (2) also have knowledge of the play’s literary and historical intertexts. A popular German audience, separated by language, geographical distance and cultural location, would have seen few, if any, of the plays that speak to Shakespeare’s fashionable staging, nor would they have understood classical allusions made in English. The author of this German-language account of an English touring production, like the French tutor in Harrington’s household, accordingly documents an understanding of Shakespeare’s text predicated upon only the simplest physical aspects of its performance – the only elements of production they had been able to understand.

Two significant aspects of current film and theatre practice have exactly the same effect as the cultural and linguistic distance that affected the degree and mode of understanding that either Petit or Menius could attain in watching a ‘foreign’ Titus. The first is the prevalence in current British and American film and theatre practice of naturalistic staging techniques, and the dominance of acting processes predicated upon psychological realism, including method acting; the second is the sometimes disorientating presence of female actors in modern performances of early modern English drama. Before I turn to the significance of these factors on the performance text that I will consider in most detail (Julie Taymor’s filmed Titus of 1999) however, I want to consider a number of key theatrical productions from recent years, in order to establish a performative genealogy for this play and the character of Lavinia during the second half of the twentieth century and onwards.

III

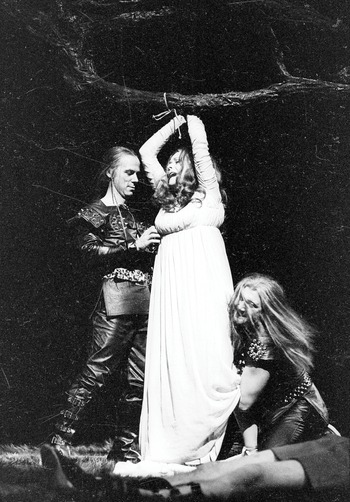

According to Milton Shulman, until Peter Brook staged Titus Andronicus at the RST in 1955 (Illustration 1), the play had ‘only been given two major productions in 100 years’; the same critic added that ‘[t]he squeamish may well wonder why there have been so many’.Footnote 12 Brook’s version of Titus is considered a landmark production that influenced theatrical approaches to the play for the next thirty years, until Deborah Warner (1987) and Bill Alexander (2003) broke decisively from its legacy.Footnote 13 Brook omitted unnecessary violence and created horror using elegant and beautiful images. Working within what he considered to be an Artaudian theatrical episteme that made much of Asian symbolism, he emphasized the stylistic nature of Shakespeare’s play rather than acquiesce with the excesses of literalized violence that Titus has sometimes suggested to less astute practitioners. A key example of Brook’s strategy was the vision of Lavinia after her rape and mutilation, in which Vivien Leigh stood in front of an abstract forest, with scarlet and white streamers flowing from her mouth and wrists. The discovery was accompanied by an eerie, slow plucking of harp strings, described as being ‘like drops of blood falling into a pool’ (Brook composed the music and ‘clashed experimentally with pots and warming pans, played with pencils on Venetian glass phials [and] turned wire baskets into harps’ in his attempts to write the perfect score).Footnote 14

1. Vivien Leigh in an abstract forest, with scarlet and white streamers flowing from her mouth and wrists (1955).

The lack of gore achieved by Brook’s rejection of naturalistic approaches to stage violence ensured that the director ‘created an atmosphere in which the [play’s] horrors [could] take hold of [the audience]’.Footnote 15 Paradoxically, the effect of this tacit elision of violence was an augmentation of the power of the play’s viscerality. According to the Daily Express, extra St John Ambulance volunteers had to be called in during the run because at least three spectators passed out each night. Other critics drew attention to the evident contradiction, claiming that the production was ‘full-blooded and bloodless’ whilst observing ‘[w]hat a gory Gala night Mr Brook could have made of it! And how triumphantly he resisted the temptation!’.Footnote 16 The Manchester Guardian observed that Brook conjured ‘dazzling simplicity out of a terrifying tawny darkness’.Footnote 17 Despite no explicit verbal reference or semiotic visual allusion of any kind being made in the production to events of the recent and traumatic past, the Times review chillingly concluded that ‘There is absolutely nothing in the bleeding barbarity of Titus Andronicus which would have astonished anyone at Buchenwald.’Footnote 18

Brook’s Titus had immense power because it was staged in ways that involved non-literal and non-naturalistic approaches to the play’s martial, homicidal and sexual violence. The director claimed that ‘the real appeal … was obviously for everyone in the audience about the most modern of emotions – about violence, hatred, cruelty, pain – in a form that because unrealistic, transcended the anecdote and became … quite abstract and thus totally real’.Footnote 19 In his attempts to achieve this theatrical ‘reality’, Brook cut the play by over 850 lines, including the entirety of Marcus’s discovery speech in Act 2, scene 3. The discovery of Lavinia was accordingly rendered as silent tableaux within an upstage discovery space, described by the promptbook thus: ‘Enter C[entre] Lavinia stands desolate … Demetrius and Chiron slowly close the column doors meeting C[entre]’.Footnote 20

Faced with the forty-seven lines of sublime poetry that Shakespeare gives Marcus at the discovery of his niece, Brook saw simply an exercise in verbal stylization and replaced words with a powerful stage image – an approach that, according to Jonathan Bate,

Answer[ed] to the first rule of strong theatrical reinvention. The long red ribbons serv[ing] as a translation of the language of the text in that they stand in the same evocative but oblique relation to blood as do such similes as that of the bubbling fountain … Brook’s innovation[s] may … be said to grow from the original script. And at the same time they speak in the new language of the post-Artaudian theatre in which stage events are ritualized and their correspondence to reality outside theatre is skewed and problematized.Footnote 21

2. Lavinia’s dress, designed by Peter Brook. Note the crumpled fabric of the underskirt, resembling tree bark.

This may well be true; nevertheless, in the early modern period, heightened audience understanding was derived from an appreciation of the emblematic nature of Shakespeare’s theatrical spectacle together with an acknowledgement of the play’s rich vein of literary and historical intertextuality. Without the combination of heavily mediated spectacle (a boy actor representing a totem of femininity, using symbolic representations of bloodshed to articulate the violence that has been enacted upon it) alongside the power of literary and historical allusion (communicated through deliberately intertextual Shakespearian verse), the scene’s philosophical importance and the power implicit in its reception are both diminished.

In the twentieth century, Brook’s production is testament to the fact that Titus can achieve significant theatrical power when its violence is rendered metaphorical, when the human bodies onstage are considered not as psychologically complete human entities, but rather as emblematic tools in the communication of raw human emotions (what Brook describes as a quality of performance that enabled his production to ‘[touch] audiences directly because [it] tapped in it a ritual of bloodshed which was recognised as true’).Footnote 22 However, to separate the play’s spectacle from its literarily and historically specific aural referents is to do much damage to its wider project. Thus Brook, in his very attempt to render symbolic (and therefore universal) the violence of Titus, inevitably tied it down to a response appropriate perhaps only to his own historical moment: a European society emerging from the annihilation of the Second World War – acts of genocide that were as yet still unspeakable amongst those who had discovered them.

Many producers of Titus in recent years have responded in like manner; such metaphorical abstractions range from Freedman in 1967 to Ninagawa in 2006 – whose Marcus likewise omitted all references to Ovid and instead keened animalistically as he encountered a kabuki-inspired symbolic representation of the mutilated Lavinia.Footnote 23

IV

So where can we find an alternative to this stripped-down, visually metaphorical but verbally cut tradition? And what alternate valences can a different approach to staging Titus in the modern world offer? The answers come from the political landscape of British imperialism towards Ireland during the 1970s. In 1972, Trevor Nunn, Buzz Goodbody and Euan Smith staged a version of Titus at the RST that rejected entirely the theatrical symbolism of Brook and its influential legacy. Nunn’s production was predicated upon stage realism and, to Colin Blakely, an Irishman who played Titus and saw numerous analogies to Conservative British politics and the occupation of his homeland, the similarities he detected between Rome and Britain (in Ireland) or America (in Vietnam) as empires in decline, led him to observe: ‘of all [Shakespeare’s] Roman plays it is the most apposite to our present time. It is quite up to date. It takes a look at an empire in decay and a system which has become so hard, so brittle, that it breaks.’Footnote 24

Nunn’s production accordingly represented violence in a naturalistic way, with the in-your-face realism of the mass media news camera. This frankness was seen as the only possibility for a team of politicized directors and actors who recognized that ‘people can see what violence is really like when they watch the news on television’, and confessed: ‘whatever we did, it would never be as horrible as that picture of the officer pushing a gun into a man’s head in Vietnam’.Footnote 25

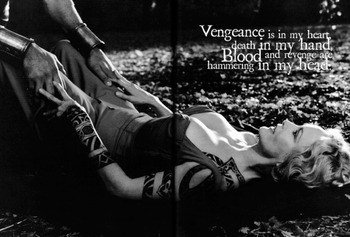

The rape of Lavinia was presented as a horrifying physical assault. Subsequent to her violation, Suzman acted a Lavinia who, due to the severity of the assault she had endured, experienced difficulty in standing upright, or in walking; she was hung up by the arms by Chiron and Demetrius during the course of their taunts and, according to Billington, presented ‘a pitiable, hunched, grotesque, crawling out of the darkness like a wounded animal’ (Illustration 3).Footnote 26 As Titus embraced his daughter upon their first post-rape encounter, Suzman ‘presse[d] against her father for comfort like some terrified animal’.Footnote 27 In the context of this ‘lingering, slow-motion realism … naturalistic weight and stress’, there was no room for Marcus’s poetic explications of his niece’s state either.Footnote 28 The RSC promptbook accordingly shows that twenty-nine of Marcus’s forty-seven lines in 2.3 were cut, including all the Ovidian ones.Footnote 29

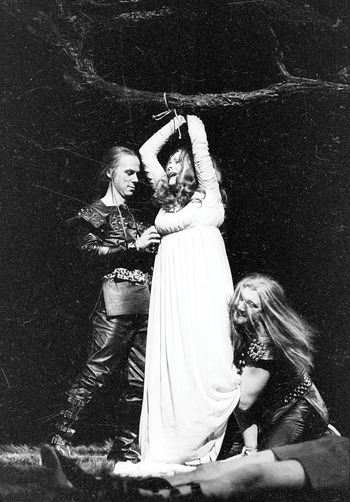

By contrast, in 1987, Deborah Warner directed an uncut version of Titus at the RSC’s Swan theatre. Dessen notes that the production

started with no overriding interpretation (or music or design concept), but rather assembled the best actors available, actors who wanted to do this script, and then went through, scene by scene, confronting each problem as it emerged, with the designer … on hand, making sketches so as to adjust design and costume choices to those ongoing decisions. The word repeated constantly among Titus personnel was trust: trust in the script, in the audience, in the Swan … in each other.Footnote 30

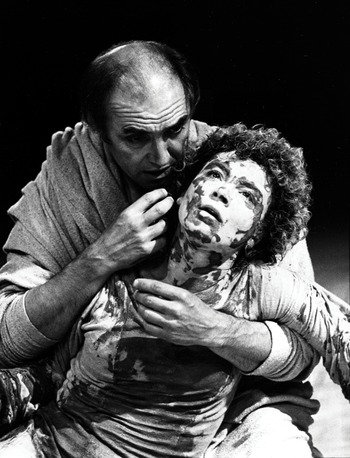

The stage of the relatively new and deliberately intimate Swan was practically bare, save for the occasional stage property, sometimes historical, sometimes modern. As a result, Warner displayed a ‘stripped simplicity of means [that] enable[d audiences] to feel the terror of a bucket, cheesewire, and a little stage blood’.Footnote 31 In Act 2, scene 3, Lavinia’s plight was indicated not by buckets of blood, but by a coating of clay or mud applied to her body, through Ritter’s posture, and in the improvised bandages that had been applied to her stumps (Illustration 4). Presented in its entirety in one of the rare examples of textual fidelity since the Second World War, Marcus’s monologue became a desperate attempt to rationalize and contextualize a horror that, precisely because of her uncle’s oral explications, was no longer specific to Lavinia (and hence utterly unknown and unexpected), but rather a horror enacted as part of a long tradition of violence against women. The staging of the scene did not, accordingly, present Lavinia as entirely subdued, the kind of quivering animal who ran to the arms of the nearest patriarch (as in Nunn); rather, ‘A two actor scene, wherein [the audience] observe[d] Marcus, step-by-step, use his logic and Lavinia’s reactions to work out what has happened, so that the spectators both [saw] Lavinia directly and [saw] her through his eyes and images.’Footnote 32 The terror was thus mediated through the poetic consciousness of Shakespeare’s reworked classical narrative and, halfway through his speech, Marcus moved to hold Lavinia – a position he held up to and including his penultimate line ‘do not draw back’, which Warner used to highlight the difficulty that Lavinia had, as a rape victim, in moving forwards either emotionally or physically from this utterly devastating moment.

4. Sonia Ritter and Donald Sumpter in Deborah Warner’s discovery scene (1987).

Nevertheless, despite fulfilling all the demands placed upon her by an uncut script, Lavinia did not seem to escape the trauma of this pivotal scene and, as the play progressed, like Suzman before her, she became ‘a sub-human … who in the final two scenes … has lived so long with the memories of Act II as to become catatonic’.Footnote 33 Ritter consequently ‘played her part in Titus’ plans but left it to the men to take the decisions’.Footnote 34 As Dessen observes, ‘Ritter responded to the challenges in Lavinia’s silences in a powerful and often disturbing fashion that signalled her status as a reflection [of] and, as a result, a victim of the men in this Rome’.Footnote 35 Theatre critics likewise saw not an active and assertive woman who became an agent of her own retribution, but a victim of and a servant to the forces of patriarchy – a point that was perhaps made most forcefully by Coveney’s description of Lavinia’s dead body, following her father’s breaking of her neck in Act 5, scene 3, as the falling of ‘a discarded dummy on a ventriloquist’s knee’.Footnote 36 Bate points out the gender-political rationale behind Warner’s interpretation:

Warner in her direction of Marcus and Sonia Ritter in her portrayal of Lavinia achieved what they did because rape matters to them as late-twentieth-century women more than it could possibly have done to Shakespeare writing for Marcus and the boy who first played Lavinia … Watching Ritter and sensing Warner behind Sumpter, one could with Marcus begin to share the rape victim’s anguish. The scene was so powerful to so many members of the audience because our culture is more conscious of rape and its peculiar vileness than many previous cultures have been: so it was that the words from the 1590s … worked a new effect in the context of the 1980s.Footnote 37

Such sentiments have influenced productions from Warner’s Titus onwards, particularly Alexander’s 2003 Royal Shakespeare Company production, for which assistant director Tom Wright and Lavinia actor Eve Myles went to a rape crisis centre for guidance, describing their experience as follows:

It was such a difficult, intense experience – we were in a place where women are daily counselled for exactly the things Lavinia has experienced. We told them the story and they said how remarkably similar it seemed to the stages people go through when they’ve been raped. The key stage that you reach at the start of recovery is to acknowledge what has happened. Lavinia chooses a very specific moment to write RAPE in the sand. That marks the beginning of her recovery. We also described the very short scene with Chiron and Demetrius after the rape and were told that rapists rationalize very quickly …Footnote 38

I would like to suggest that a combination of the entirely understandable and ethically proper gender-political imperatives of modern directors in relation to the representation of the act of rape and its consequences, and their less defensible reliance on psychological realism and emotion-recall-based, Stanislavskian systems of actor training and rehearsal to achieve them, has led modern theatre and cinema into a performative cul-de-sac in which more credence is given to prevailing sociological constraints and moral contexts than to either the Shakespearian play-text or its historical and literary intertexts. For a director to guide an actor who is to play Lavinia towards a rape crisis centre rather than to offer her copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and a selection of feminist readings that articulate patterns of resistance within those difficult narratives, is to place the performer in a social and psychological context that neither suits the play, nor from which it is easy to escape. Certainly, if psychology, understood through verbal articulation, is to be the exit strategy, then Shakespeare’s play-text offers no way out – because Lavinia never tells us how she feels. She cannot. In addition to the manifest inaccuracy of the assumption that they ‘were in a place where women are daily counselled for exactly the things Lavinia has experienced’, in taking recourse in psychology and the trauma of real, lived human experience, Wright and Myles (like most modern directors and actors who approach the role of Lavinia) were closing off many more performative possibilities than they were opening up.

In contrast, by incorporating Ovid at the moments he does, Shakespeare not only locates Lavinia’s rape within a narrative tradition in which there is clear classical precedent for the actions that have happened, but also within one that powerfully adumbrates the events of retribution that are to come. The dramatist also significantly offers a route to redemption and release that is predicated not merely upon the vengeful acts of Lavinia’s male family members, but upon those of the sufferer herself – an intertextual frame of reference that powerfully foreshadows the female vengeance that is to come and highlights not only Lavinia’s role in the capture and mutilation of Demetrius and Chiron, but her eventual corporal release from the torment of physical and emotional suffering.Footnote 39

V

Classical scholarship of approximately the past thirty years has demonstrated the ways in which Ovid’s poetic output evinces ‘recognition of aspects of [the female] condition that are only now becoming common currency’. In particular, Metamorphoses, which contains approximately fifty instances of ‘forcible rape, attempted rape, or sexual extortion hardly indistinguishable from rape’ provides analyses of the ways in which patriarchal oppression and predatory sexual expectation are endured, avoided and revenged by female characters.Footnote 40 In certain instances, Ovidian rape entirely dehumanizes its victims, partly because an overriding generic telos of the Metamorphoses is to lead its characters towards final acts of transformation from human into animal or vegetal states. As Curran observes, in Ovid:

Rape does worse than undermine a woman’s identity; it can rob her of her humanity [therefore] transformation into the non-human is uniquely appropriate in the case of rape, for the process of de-humanisation begins long before any subsequent metamorphosis of the woman’s body. The transition from human to sex object and then to object pure and simple proceeds by swift and easy stages, its onset being simultaneous with the decision to commit rape. The final physical transformation of so many rape victims is only the outward ratification of an earlier metamorphosis of the woman into a mere thing in the mind of the attacker and in his treatment of her …Footnote 41

The Ovidian character who best exemplifies the dynamic of desire, objectification, transformation and inertia is Daphne, the nymph who in her desire to flee the advances of Apollo, is transformed into a tree. In Daphne, Ovid writes version of female experience in which the only line of defence when faced with unconstrained male sexual desire is to become an inanimate material substance incapable of being raped because it does not possess the reproductive biology of human, divine or animal worlds. Daphne avoids ravishment, true, but at the significant price of giving up her human form – and it is important to remember that this was a form that not only led to Apollo’s desire of her, but also constituted the corporeal frame in and through which Daphne had been able to perceive of and engage with the world. In phenomenological terms, therefore, Daphne’s metamorphosis is not merely a loss of agency, it is rather a retreat from all sentient existence as ontological subject. Moreover, such an exit from the world of apprehension and agency seems to be prefigured into Daphne’s culturally encoded identity as woman, because ‘[a]s Daphne runs from Apollo, the effect of the wind on her fluttering clothing and streaming hair corresponds closely to what the wind will do to the branches and leaves of the tree she is to become’.Footnote 42

This physical similarity between the object of Apollo’s desire and the objectified tree that is Daphne’s teleological destiny is disturbing enough; but what is perhaps more shocking is the willingness of critics to ascribe its non-human, ontologically absent characteristics to the experience of the real women who have been raped throughout history:

After her transformation, Daphne as tree is an exact analogue of a victim so profoundly traumatized by her experience that she has taken refuge in a catatonic withdrawal from all human involvement, passively acted upon by her environment and by other persons, but cut off from any response that could be called human. Ovid’s language describing what he and Apollo choose to take as the laurel’s ‘reactions’ (l. 556 and 556–7) has an eerie but psychologically correct ring to it.Footnote 43

The impassive inertia of the rape victim detected here resonates chillingly against the ‘catatonia’ also perceived by the performance critic, Alan Dessen in relation to Ritter’s portrayal of Lavinia. Such a response to the act of rape in textual or performative terms as inertia, absence, the closing in and off of any ability to engage sensorially, corporally and articulately with the world, is also chillingly seen as being ‘psychologically correct’ by both men.

Fortunately for feminist critics and modern theatre practitioners interpreting the Ovidian influences acting in and through Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, Daphne is not the most prominent intertextual referent pointing towards the modalities of Ovidian rape in the play. Lavinia is much more frequently and systematically compared, by both Shakespeare and his critics, to Ovid’s character Philomela, the sister-in-law raped by Tereus and tormented by him in her still living, still human form through having her tongue cut out and being forced to continue her life in a sequestered, mutilated, silenced form. Unlike the tale of Daphne, however, in Philomela’s story the protagonists remain for a long time unremittingly human. As Marder observes: ‘While most of the preceding Ovidian tales depict conflicts between human and divine figures, present confusions of animal and inanimate worlds, and involve magical or supernatural operations, the story of Philomela is presented as a human drama among characters who are endowed solely with human powers, proper names, and social positions.’Footnote 44

Because the detailed narrative events of Ovid’s tale of Tereus, Procne and Philomela are central to my argument, I will summarise them here: Tereus, a Thracian king, marries a woman called Procne and brings her to his home in Thrace. After a brief period, Procne becomes homesick for her sister, Philomela, and implores her husband to return to her father’s home in order to solicit Philomela as a companion for his new wife. Tereus consents and travels to Procne’s father’s house, where he sees Philomela for the first time. Upon seeing her, he is consumed with a burning passion, and convinces the father to consent to Philomela travelling back to Thrace, ostensibly as companion to her sister. On their arrival in Thrace, however, Tereus drags Philomela into a forest, tells her that he is going to rape her, then rapes her. When Philomela threatens to speak out concerning her ravishment, Tereus cuts out her tongue and rapes her once again. Tereus then locks Philomela in a cottage in the forest. Unable to speak, Philomela uses a loom in the dwelling to weave a communication relating to her rape, using red thread on a white background. She sends the cloth to her sister, Procne. Upon receipt, Procne uses the pretext of a Bacchic festival as an excuse to leave Tereus’s palace. She then dances her way to the cottage in which Philomela is imprisoned. She immediately brings her sister back to the palace and plots appropriate revenge. Although Procne considers castrating Tereus or cutting out his tongue, she is finally moved by the physical similarity between Tereus and their son, Itys. She therefore stabs Itys, decapitates and disembowels him, and puts the remaining cuts of his human flesh into a stew, which she serves to Tereus. As he eats, Tereus asks to see his son; at which point Procne tells Tereus that Itys is now in his stomach. Philomela enters, bearing the decapitated head of Itys, which she throws in the King’s lap. When Tereus draws his sword to kill the two sisters, all three protagonists are turned into birds and fly away.

Marder argues that Ovid’s tale of Philomela is not simply a powerful exemplar of male aggression and female revenge, but, precisely because its figuration of the male violation of women is framed in relation to access to language, it acts as a metaphor for the modern feminist project.

The text appears to stage two ‘rapes’: one ‘literal’ and the other ‘symbolic’. While one might assume that the literal rape rapes the body and the figurative rape violates access to speech, the text reverses these two registers. The first actual rape is accompanied and preceded by a speech act that announces the crime. The act of speaking rape is supplemented by the act of ‘raping’ speech – the cutting off of the tongue – that occurs later. Between these two acts comes the act of sexual domination. The Latin text insists on the convergence between speaking the crime and doing the deed: ‘fassusque nefas et virginem et unam vi supererat … [the crime being spoken, he overwhelmed the virgin, by force, all alone]’ (l. 524 …). One cannot speak ‘rape’ or speak about rape, merely in terms of a physical body. The sexual violation of the woman’s body is itself embedded in discursive and symbolic structures …Footnote 45

These ‘symbolic structures’ relate most profoundly in feminist terms to the ways in which silenced and violated women (all women within a patriarchal world) must, if they are to escape oppression, take ownership of, subvert and refashion male discourses and behaviours in order not only to assert their rejection of such oppression but also their right to exist in a world that exists outside patriarchy and its linguistic and behavioural confines. But the journey is not a straightforward one, and, despite an ostensibly Maenadic enactment of revenge, Ovid’s story does not immediately allow escape from patriarchy, but rather draws attention to the cycles of violence, disenfranchisement and atrocity that inevitably spring from it. To Marder, therefore,

The text invites a feminist reading not only because it recounts the story of a woman’s rape, but also because it establishes a relationship between the experience of violation and the access to language. Unable to speak, Philomela weaves the story of her rape. Only after she has been raped and mutilated does Philomela attempt to write. Through weaving, she writes the story because she cannot speak, and the only story she has to tell is that she has lost her voice. She writes out of necessity and in response to violation, but that writing is bound by the terms of violation.Footnote 46

In raping his sister-in-law, Tereus has violated not just the order of familial relations but also the patriarchal order itself. It is for this reason that, in the moment in which Tereus seizes Philomela’s tongue and moves to cut it out, Ovid has her tongue call upon patriarchal authority to defend her: ‘he seized her tongue with pincers, as it protested against the outrage, calling ever the name of the father [et nomen patris usque vocantem] and struggling to speak, and he cut it off with merciless blade’ (lines 555–60). At this moment of mutilation, the only language (lingua) that Philomela’s tongue (also lingua) can speak is that of patriarchal authority; and the only response that comes from a male in the light of her invocation of ‘the name of father’ is one of abuse and violation. Thus Philomela is ‘doubly silenced, first by the rapist, and then by the paternal law itself. [Her] tongue speaks only the language of the law: the name of the father. While the horror of the rape violates the paternal order, the effects of the rape disclose the implicit violation by the paternal order.’Footnote 47

In Ovid’s narrative, once Philomela has experienced this third, metaphorical rape (the first being the announcement by Tereus of his intentions, the second being the physical act of his raping her), she begins of necessity to seek means of articulation through embodied discourses: she weaves, she dances, she cuts, she cooks, she throws, she sings as a bird. It is in the moment of literal and metaphorical rupture that is constituted in/by the rape that Ovid’s text begins to provide the possibility of resistance. Interestingly, therefore, there is no definitive indication in the Metamorphoses that Philomela uses either script or language as a means of communication subsequent to her violation. Indeed, the most significant things about Ovid’s description of the tapestry she produces for Procne (her textile but not necessarily textual message) are its emphasis on the colours of the woven document (red and white) and its use of ‘signs’ [notas] (line 577) – which, in addition to denoting the marks of writing on a page, can be used in Latin to mean ‘rupture or puncture’, ‘branding’, ‘observation’ or ‘visual record’. Thus, while Marder is correct to observe

the Latin text implies that the story of Philomela’s mutilation and rape is communicated by neither words or pictures. The purple words on a white background figure the bloody writing as tattoo marks on a branded body. Although alienated from her body, this form of writing through weaving represents and writes the mutilated body … [t]his is a form of writing born from a violation of speech; its clarity and urgency derive from marks of pain. But the language that is derived from pain and mutilation can say nothing outside a discourse of pain and mutilationFootnote 48

the significant retreat in the Ovidian text from the world of language to a world of embodiment is also deeply significant here.

In the feminist discourse of theorists such as Butler and Kristeva, a retreat from language towards embodiment, and particularly embodiment in and through abjection, allows for the creation of a more significant site of resistance than that which is possible through male-authored languages and socialized modes of thought/behaviour.Footnote 49 In a corporeal world that rejects the primacy of language, an emphatically embodied evocation of the female other can defy, and eventually replace, the patriarchal order. This is what the Philomela myth tells us. And it is why the transformation at the end of it is so radically different from that at the end of the myth of Apollo and Daphne. Thus while Tereus’s transgression is communicated by the male rapist most emphatically in linguistic terms (before he commits the act of rape he must name it, and subsequent to the act itself he seeks to control knowledge of his crime through control of the access to the means of linguistic production: Philomela’s patriarchally instructed lingua), Philomela’s, and subsequently Procne’s, route(s) to the destabilization of Tereus’s patriarchal authority are all intensely corporeal. When Philomela’s textile expression of history and identity arrives with Procne, the response it provokes in her sister is silence: ‘evolvit vestes saevi matroni tyranni fortunaeque suae carmen miserabile legit et (mirum potuisse) silet: dolor ora repressit, verbaque quaerenti satis indignantia linguae defuerunt, nec flere vacat [opening out the fabric, she reads the wretched state of her sister (a miracle that she is able to) and she is silent. Grief represses her mouth and her questioning tongue fails to find words equal to her rage nor could she weep]’ (lines 582–6).

Next, Procne’s use of a Bacchic festival as the pretext for her flight to rescue her sister furthers Ovid’s exploration of the embodied female other as radical agent. She dances away from the patriarchal world represented by the palace to the forest, the locus of male desire and sexual violence in which Philomela waits; the pair then use Bacchic dance as a means of escaping the confines of the forest. In all their actions, Procne and Philomela embody and enact corporeal sites and behavioural modes of resistance that are mediated not through words but in action. When ‘Procne, rejects a logic of symmetry or exchange [and] refuses to take a tongue for a tongue, or even a penis for a tongue [and when] the weapon that is stronger than the sword is a language fuelled by excess instead of loss’, each articulation of this new ‘language’ is a corporeal one.Footnote 50 Such ‘languages’ of female agency – motion, action and revenge – are never articulated phonetically or scripturally; rather, they are articulated in performative iterations of movements that are either culturally or generically associated with the female body, or inversions of acculturated female functions such as birthing, sustaining, or nurturing human bodies. Thus Procne

stuffs [Tereus’s] mouth and belly with the body of his son, leaving Tereus no room for words. Procne violates her husband by making him gag on the law of the father; she arrests the progression of paternity by feeding him his own child through the mouth. Procne thus uses her own child as a substitute for a tongue. She speaks through her child, forcing the child into her husband’s mouth and belly. In the body of the father, the belly becomes the place of the tomb instead of womb. Rather than relying on a logic of exchange and a discourse of loss, Procne transgresses the boundaries of the male body by forcing it to assume the presence of another. Metaphorically, Procne turns Tereus into a pathetic mimicry of a sterile, masculine maternity.Footnote 51

In such a move, all patriarchy is mocked, muted and overcome.

VI

Despite her opinion that Titus Andronicus ‘speak[s] directly to our times’, Julie Taymor’s film adaptation gains much of its power from its refusal to render Titus as a simile for any event with which a modern audience could easily identify.Footnote 52 The film’s aesthetic laudably embraces a deliberate eclecticism with regards to historical costume, architectural location and the selection of stage properties.Footnote 53 Such plurality militates against audiences interpreting the film’s temporal and/or geographical location with any degree of specificity. Taymor accordingly resists the impulse of many directors to render aspects of the violence in Titus literal, to speak of the way in which they are ‘excited by the play because it seems so contemporary’, to render it a story about real people, or to treat it as a simile for mid-twentieth-century European fascism, the ethnic genocide in Rwanda, the religious ‘cleansing’ of Bosnia, or any other contemporary conflict.Footnote 54 In this respect, her film works well because it echoes what we can presume of the original production’s visual style (at least in relation to that notoriously problematic early modern representation of the play, the Peacham manuscript).Footnote 55 Taymor’s non-naturalistic treatment of the Roman army, her pan-historical depiction of political struggles between Bassianus and Saturninus, her use of puppetry, blue screen graphics and time-slice photography are all excellent translations of the play’s original juxtapositional textual and performative modalities into modern media, which contribute to the overall success of the film. Yet there is one significant respect in which I consider Taymor’s adaptation to be seriously flawed: her treatment of the rape of Lavinia.

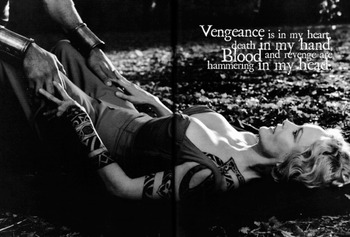

The fifteen minutes of Act 2, scenes 2 and 3 sit uncomfortably with most of the rest of the film because here the director chooses to have the action rendered extremely brutally and naturalistically. From the opening duologue between Tamora and Aaron, the performances are characterized by overt physicality and a hyper-sexualization of the female bodies presented. In the case of Aaron, the lusty performance he is directed to provide runs counter to the sense of nearly all of the speeches he delivers (in which he rejects Venus in favour of Saturn and places his desire for revenge above any sexual desire that Tamora encourages him to have). Significantly, Taymor uses the bodies of the female performers she has cast to provide repeated images of the eroticized and fetishized female form. This is true of her representation of both Lavinia and of Tamora (the latter of whom begins to undress, is caressed on the neck, breasts, buttocks, thighs and belly by Aaron – who also places his fingers in her mouth and kisses her repeatedly, before she dresses once more with almost post-coital luxury). Taymor’s spin-off publication, intended to capitalize on the success of her film, Titus: The Illustrated Screenplay, makes the point even more graphically as the recumbent body of Jessica Lange spreads across pages 74–5 in the manner of a pornographic centrefold (Illustration 5). From the entrance of Demetrius (04:37)Footnote 56 and Chiron (04:55), the voyeuristic realism of Taymor’s scene is augmented by an immediacy achieved through the cinema verité technique of circling hand-held camera shots rapidly intercut to provide shifting perspectives every few seconds. The attack of Chiron, and Demetrius, both participated in and overseen by their mother, is sold to the cinema audience as documentary fact. The Screenplay provides further evidence of this directorial intention through the use of slightly blurred cinematic frames and grainy black and white photo-journalistic shots (one of the rare occasions the book uses black and white images) (Illustration 6). In the film, Lavinia’s gloves are stripped fetishistically (07:44) and Demetrius is made to lick Lavinia’s naked hand (07:52) prior to straddling her from behind and cutting the buttons from the back of her dress with a knife in close-up (08:18). Chiron subsequently swaps positions with his brother, straddles Lavinia from behind and rips open her dress, once again in close-up, to reveal Lavinia’s naked back together with the straps and bodice of a low-cut corset (08:24). A reverse shot is provided next, in which Lavinia clutches her black dress against her stripped torso in an inadvertent revelation of first one shoulder and then both, together with a view of her falling corset straps (08:28). The scene is disturbing; it invites audiences to contemplate both the trauma of rape and the pleasure of highly eroticized, fetishistic sexual intercourse. It is an audacious directorial choice and, like that of other recent stage directors, it is intended to bring home the social reality of rape, together with a notion of the personal desecration it entails.

6. Black and white still from Titus: The Illustrated Screenplay. Note the grainy nature of the image, evocative of high-speed, low-light news photography, and the limited depth of field.

The problem with such a deliberately scopophilic treatment of the female body, however, is that it goes against the sense of Shakespeare’s writing. Lavinia’s plea to Tamora to ‘tumble me into some loathsome pit / Where never man’s eye may behold my body’ (2.3.176–7) sits somewhat awkwardly with a scene in which (1) so much visual use is made of both Lavinia’s and Tamora’s fetishized anatomy and (2) both shot choice and aesthetic approach focus the audience’s attention on the immediacy of one particular human subject’s graphically real situation.Footnote 57 The naturalistic, documentary, almost photo-journalistic style chosen by Taymor to communicate the beginnings of what will culminate in a double rape, not only creates a performance that has more to do with the objectification of the female form in the medium of contemporary pornography than it does Shakespeare’s play-text, but also presents what is happening as a series of real and frightening events.Footnote 58 In terms of its representation of the social reality of rape, this is a commendable set of decisions. But, given that the scene in Shakespeare is a linguistic precursor to the violence that takes place, quite deliberately, offstage and in which spectators are accordingly rendered complicit with the act of violence as a result of the fact that they are required to produce in their own mind’s eye versions of the rape of Lavinia during the action of the pit scene (albeit guided by Shakespeare’s poetic description of the briars that cover it), the fundamental dramatic function of both Shakespearian scenes is lost. Hence, through the strategies of naturalism, cinematic immediacy and the important fact that Taymor provides her spectators with documentary evidence of other people committing this act, the essential point is entirely lost that violence that is not seen theatrically or cinematically must be imagined and therefore renders auditors not only complicit in but also responsible for any and all acts of atrocity that they imagine. Put simply, it is easy for us to condemn Demetrius and Chiron in this film, because we do not mentally commit the act of rape for them.

The full effect of Taymor’s decisions to victimize Lavinia absolutely, however, is not seen until the discovery scene of Act 2, scene 3, in which Taymor slowly returns her audience to the symbolic impressionism, expressionism and abstraction that characterize so magnificently the majority of her film. The audio/visual treatment of Marcus’s discovery speech intercuts images of the speaker with sustained shots of the raped and mutilated Lavinia, over which the speech continues. By means of this subtle visual intercutting, Taymor is able to exploit a naturalistic version of the cinematic device of the voiceover – a technique that enables Marcus’s lines prior to the opening of Lavinia’s mouth to be laid over a bravura tracking shot that eventually cranes upwards as blood falls from the mutilated Lavinia’s gaping mouth. The affective power of this moment is augmented by a stylized rising ‘scream’ in Goldenthal’s orchestral underscoring (the music is present from the moment it is faded in over an establishing atmosphere of cicadas and birdsong, ten seconds after the scene’s beginning and at Marcus’s line ‘Who’s this? My niece?’).

This is undoubtedly powerful cinema. It is an uncomfortable moment of visual spectacle that makes much of the opposition between viewers’ appreciation of the aesthetic beauty of Taymor’s cinematography and their revulsion at the horror that it depicts. Such representation has a price, however, and the way that this moment has been aesthetically achieved makes its images so shocking that spectators need time to contemplate the full terror (and beauty) of what they are witnessing. Accordingly, a thirty-two-second silence follows the falling of blood from the windswept Lavinia’s mouth. It is an eternity of screen time, accompanied only by a falling topos of grief in Goldenthal’s Debussy-like, impressionistic score.

Unquestionably this is a major moment of Shakespeare cinema history but the cost is great, because it is not just Lavinia who is silenced in the sensory overload of Taymor’s representation: Shakespeare’s voice is also muted in this treatment, because the thirty-two seconds of verbal silence that Taymor needs for her audience to come to terms with her metaphorically beautiful vision of the ugliness of the results of male brutality replace some thirty lines of text.Footnote 59 Significantly, yet unsurprisingly given the genealogy of performance outlined above, these are lines that resonate within the intertextual history of literary considerations of sexual barbarity against women; references that add weight and significance to the rape of Lavinia, rendering it more than the representation of a single woman’s plight.

Compounding this focus on Lavinia’s pitiful, victimized silence and state of inertia is the fact that Taymor chooses to locate the scene in the muddy, marshy area of a river delta, with shattered sticklike trees protruding from the riverbed’s churned-up mud. The vista is evocative of Augustus John’s expressionistic scenery for the World War I scenes of The Silver Tassie (1928), or photographic stills of devastated Flanders battlefields. In this mutilated landscape of shattered trees, which clearly alludes to iconic images of nature assaulted by men, Taymor has decided to place Lavinia on a shattered stump, with twigs sticking into her own ‘stumps’ as a visual incarnation of the mockery of hands promised to her by Chiron and Demetrius. The result is perhaps the most powerful image of Lavinia as Daphne to have been created in the performance history of Shakespeare’s play.Footnote 60

The tenor of this awkward static victim representation continues in the film’s fourth Penny Arcade Nightmare (PAN): which re-presents Lavinia’s rape as a psychological haunting. Taymor inserts this mental flashback during the revelation of Lavinia’s attackers (prompted by a copy of Ovid) and the inscription of [STUPRUM] CHIRON DEMETRIUS in the sand. Here, Taymor makes a brave decision to have Lavinia reject Marcus’s textual instructions to take the phallically figured stick in her mouth and between her hands in a moment of re-engagement with language through inscription that would simultaneously symbolically refigure her own violation. Yet, despite this, once again, the chosen mode of performance is based on fixation with psychological remembrance of the defilement of the victim, this time through memorial reconstruction in which Taymor presents iconic images of the objectification of Lavinia as an object of male desire/attack. Now taking the form of Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch (Illustration 7), Lavinia in her own memory is ‘rooted’ on a classical pedestal, attacked by Demetrius and Chiron in the form of tigers and transformed into a fawn, with a doe’s head and hooves, which she uses to try to keep her billowing skirts in check (Illustration 8).

Taymor states that she devised the concept of the PAN (used throughout her film) ‘to portray the inner landscapes of the mind as affected by the external actions’, arguing that ‘[t]hey depict in abstract collages, fragments of memory, the unfathomable layers of a violent event’.Footnote 61 Ironically, of course, by choosing to retreat into Lavinia’s psyche and represent her imagined remembrance of rape as a visual essay in victimization, Taymor inadvertently inverts and thereby negates the narrative of Ovid, according to whom, in their revenge, ‘[Procne] pounced on Itys, like A tigress pouncing on a suckling fawn … And dragged him to a distant lonely part Of the great house… struck him with a knife [as] Philomela slit his throat’ (636–42). The original Ovidian imagery is a figuration of Maenadic female revenge, yet this possibility is usurped in favour of the so-called trauma psychology of the objectified rape victim.

VII

The danger in seeing a character like Lavinia in a play like Titus Andronicus from the perspective of only our own cultural moment (and its political and gender-political agendas), is that we render the cultural, geographical and historical dialogue upon which Shakespeare’s play is based simply a route of transmission – and even there, one in which the line can easily go dead. Conventional understandings of ‘source study’ see the relationship of Shakespeare and the classics as a one-way street from antiquity to the Renaissance and perhaps not beyond. I want, however, to posit a version of literary, historical and performative intertextuality that is based upon exchange: for if antiquity renders up its texts for Shakespeare (and for us), what is required of us during the processes of production and performance is to give back the sense of honour and respect that comes from listening, reading and interpreting them. If we close the borders with antiquity, if we consider Shakespeare’s classical allusions to other lands, times and cultures to be unstageable and inappropriate to our own, then we lose not only the possibility of understanding Greek and Roman history, culture and literature through Shakespeare, but also the possibility of understanding Shakespeare himself, because for Shakespeare, the classics held deep meanings, not only for his own, but for all historical periods.

In one of the best essays to have been written about Lavinia in recent years, Katherine Rowe criticizes the tendency of certain feminist critics to read her as an emblem of the absolute oppression of the female – a position of subjugation characterized by the violated woman. She suggests that Lavinia should instead be seen as an emblem for the general loss of agency in the play and thus Titus’s counterpart, not his opposite.Footnote 62 For such an argument to make sense, the character needs to be connected to the Lavinia of Virgil’s Aeneid, to the Lucretia of Livy’s Histories and Ovid’s Fasti, as well as to Shakespeare’s explorations of the same subject in The Rape of Lucrece; most importantly, however, she must also be connected to the Philomela of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Her plight must be seen from multiple perspectives in a deliberately transhistorical, transcultural and intertextual frame of reference, rather than from the purely personal and psychological ones that characterize our own times. It is difficult for modern directors to do this, for as Dessen has observed,

theatrical professionals … place great emphasis on ‘realism’ in the narrative and in the motivation of … characters, but, especially in this early Shakespeare script, the images (for both the ear and the eye of the spectator) can be especially strong and can exhibit their own logic and consistency. Our sense of theatre or staging, often controlled by unacknowledged assumptions about naturalism, can at times collide with the rationale behind a playscript designed for a pre-realistic stage without any pretence to ‘theatrical illusion’ at a time when the major literary event was the emergence of Books I–III of The Faerie Queene.Footnote 63