W arburgia salutaris is a popular medicinal tree in southern Africa, where there is widespread use of medicinal plants (Van Wyk, Reference Van Wyk2011). Stem bark is the most commonly used part of the tree, and leaves and roots are also used. It is claimed to treat numerous illnesses, including bronchial infections, colds, gastric ulcers, malaria, oral thrush, rheumatism, sinusitis and venereal diseases (Van Wyk, Reference Van Wyk2011; Maroyi, Reference Maroyi2013; Leonard & Viljoen, Reference Leonard and Viljoen2015), and several phytochemical and pharmacological studies attest to its medicinal value (Rabe & van Staden, Reference Rabe and van Staden2000; Madikane et al., Reference Madikane, Bhakta, Russell, Campbell, Claridge and Elisha2007; Mohanlall & Odhav, Reference Mohanlall and Odhav2009; Green et al., Reference Green, Samie, Obi, Bessong and Ndip2010). However, such popularity makes it a sought-after species, resulting in overharvesting, mainly for illegal trade (Botha et al., Reference Botha, Witkowski and Shackleton2004). Consequently, it is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Hilton-Taylor et al., Reference Hilton-Taylor, Scott-Shaw, Burrows and Hahn1998). In Zimbabwe it is categorized as Extinct in the Wild (Maroyi, Reference Maroyi2008) and exists only in cultivated populations (Maroyi, Reference Maroyi2012). In South Africa it is categorized as Endangered and is in continual decline (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Geldenhuys, Scott-Shaw and Victor2008), and in Swaziland it is categorized as Critically Endangered (Dlamini & Dlamini, Reference Dlamini, Dlamini and Golding2002).

Prior to this study there were only four occurrence records of W. salutaris in Swaziland, at Bulunga (Compton, Reference Compton1976), Malolotja Nature Reserve (Dlamini & Dlamini, Reference Dlamini, Dlamini and Golding2002), Shewula and Mlawula (Loffler & Loffler, Reference Loffler and Loffler2005), and no specimens were held in the Swaziland National Herbarium. However, discussions with foresters, traditional healers and local people revealed that subpopulations existed at other locations in the country. We conducted a country-wide survey to map the distribution of the species, estimate its population size, record threats, and revise its conservation status. This was done as part of formulating a conservation strategy to ensure sustainable utilization of the species and maintenance of genetic diversity. Given the widespread use of traditional medicine in Swaziland (Amusan, Reference Amusan, Juliani, Simon and Ho2009), such a popular medicinal plant is vulnerable to overexploitation and ultimately extinction.

Field surveys were conducted during November 2011–December 2012 in representative areas of all physiographic regions of Swaziland. Five park rangers and 33 local people (traditional healers, herdsmen and plant enthusiasts) assisted with surveys in five protected areas and 15 unprotected areas, respectively. These study sites were identified through discussions with reserve managers and community leaders. As W. salutaris is popular and easy to identify, they had no difficulty leading the researchers to its exact locations, and some suggested potential locations beyond their villages, which turned out to be correct. Eighteen voucher specimens were collected and deposited in the Swaziland National Herbarium. Geographical coordinates, habitat characteristics, number of individuals (mature and juvenile), and physical damage to the plants were recorded. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the rangers and local people to ascertain the uses of W. salutaris, threats to the species, and its conservation status.

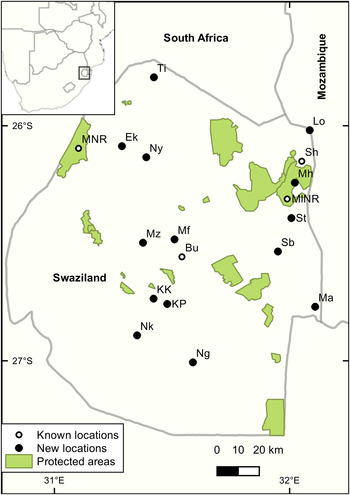

We assessed the extinction risk of W. salutaris in Swaziland using IUCN guidelines (IUCN, 2012a,b), applying criterion B, which considers the species’ geographical range, number of subpopulations, decline in habitat quality and number of mature individuals. Unlike other criteria, all data required for criterion B were available, facilitating an accurate assessment. A distribution map was plotted using QGIS v. 2.2.0 (QGIS Development Team, 2014). The area of occupancy (AOO) and extent of occurrence (EOO) were calculated using the GeoCAT tool (Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Moat, Hill, de la Torre and Scott2011).

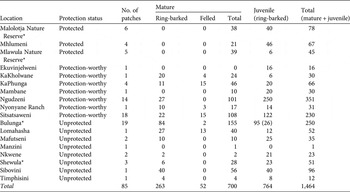

Eighteen locations of W. salutaris were found, 14 of which were new records (Table 1, Fig. 1). The species occurs in small isolated patches, with 1–19 patches per location (Table 1). Three locations (16.5%) were in protected areas, and seven (38.9%) were in unprotected areas worthy of protection, as defined by Roques (Reference Roques2002) based on biological and social importance and threats to biodiversity. Formal protection of these protection-worthy areas would thus conserve at least 55% of the species’ locations, provided harvesting was curbed. The largest subpopulations occurred in two protection-worthy areas, Ngudzeni and Sitsatsaweni (351 and 230 individuals, respectively), and in one unprotected area, Bulunga (250 individuals) (Table 1). We conclude that the previously sparse number of records of the species was attributable to lack of research rather than a paucity of the species in Swaziland.

Fig. 1 Distribution of locations of Warburgia salutaris in Swaziland. Bu, Bulunga; Ek, Ekuvinjelweni; KK, KaKholwane; KP, KaPhunga; Lo, Lomahasha; Ma, Mambane; Mf, Mafutseni; Mh, Mhlumeni; MlNR, Mlawula Nature Reserve; MNR, Malolotja Nature Reserve; Mz, Manzini; Ng, Ngudzeni; Nk, Nkwene; Ny, Nyonyane Ranch; Sb, Sibovini; Sh, Shewula; St, Sitsatsaweni; Ti, Timphisini.

Table 1 Locations of Warburgia salutaris in Swaziland (Fig. 1), with habitat protection status, number of patches per location, and numbers of mature and juvenile individuals.

*Previously known locations

Seven hundred mature individuals were recorded, of which 263 (38%) had been ring-barked and 7% were felled and debarked (Table 1). Juveniles were also ring-barked where mature individuals had been destroyed (Table 1). Such indiscriminate harvesting was observed only in unprotected areas, and all respondents attributed it to illegal trade. The need for supplementary income to alleviate poverty (48%), poor law enforcement (36%), and ignorance of the value of biodiversity (16%) were cited as drivers of the illegal trade. A decline in the number of mature individuals is inevitable if such indiscriminate harvesting persists. Soil erosion and invasive alien plants were prevalent in most of the unprotected areas, indicating a decline in habitat quality, and the occurrence of W. salutaris in small isolated subpopulations constitutes a severely fragmented distribution. Thus, despite not being as rare as previously supposed, the species is threatened.

The AOO and EOO were calculated to be 192 and 10,436.62 km2, respectively. Although the EOO falls below the threshold for the Vulnerable category, the AOO corresponds to the Endangered category. Considering the ongoing decline in number of mature individuals and habitat quality, the severely fragmented distribution, and the EOO of < 500 km2, W. salutaris, in Swaziland, meets the criteria for categorization as Endangered (EN B2ab (iii,v)). Although this represents a decreased extinction risk compared to the previous national assessment by Dlamini & Dlamini (Reference Dlamini, Dlamini and Golding2002), it does not imply an improvement in conservation efforts but rather a more accurate assessment based on more data.

Potential interventions cited in the interviews were improved law enforcement to curb illegal trade (61% of respondents), cultivating the species to relieve the pressure on wild populations (22%), and raising awareness about the value of biodiversity among community members (17%). This study has clarified the conservation status of W. salutaris in Swaziland and identified previously undocumented wild subpopulations. We recommend that this information be used in setting priorities for conservation of the species, and in updating the global status of the species on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2015). We will share our findings with conservation authorities in Swaziland to help guide conservation planning.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by Bioversity International, through the Abdou-Salam Ouédraogo Fellowship to MND, and the University of Swaziland. We thank the Swaziland National Trust Commission for providing access to protected areas and allowing their rangers to participate in the study. We also acknowledge the various individuals from local communities who readily participated in surveys.

Biographical sketches

Meshack Dludlu studies plant systematics and conservation. Priscilla Dlamini works on collaboration between traditional and conventional health practitioners. Gugu Sibandze studies pharmacological properties of medicinal plants. Vusumuzi Vilane works on the protection of indigenous knowledge systems. Cliff Dlamini conducts research on policy, socio-economics, and commercialization of non-timber forest products.