Introduction

The social category “people of color,” which first appeared in the United States in the late 1700s and faded in the mid-nineteenth century, has re-emerged since the 1970s and now occupies a central place in thinking about the racial order. Revived in the Black, progressive, and feminist movements, the term has entered mainstream journalism, the social sciences, and the everyday language of politics. Who is and who is not a “person of color” has become a matter of consequence in a variety of social contexts.

Originally, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, “people of color” designated an intermediate group in slave societies (the “free people of color”), while also serving as an umbrella category for non-whites, enslaved and free, including Blacks, those of mixed racial ancestry, and (in some contexts) the Indigenous. In its revived use since the 1970s, “people of color” has again become an umbrella term for non-whites, this time with broadened boundaries reflecting demographic change. During the same period, the panethnic categories Hispanic/Latino/LatinxFootnote 1 and Asian American have emerged as bases of collective organization and personal identity. Since “people of color” now encompasses both Hispanics and Asians as well as Blacks, Native Americans, and other groups, it takes panethnicity to a still higher level, often two steps removed from individuals’ primary ethnoracial identification. The boundaries of the category are hazy: Are Hispanics or Arab Americans people of color if they self-identity as white? Despite such ambiguities, “people of color” has become, at least for some Americans, a basis of inter-ethnic solidarity—what Efrén O. Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) calls a “person-of-color identity,” distinguishable, he argues, from identification with the particular groups that the term “people of color” embraces.

The ambiguities and ambivalences surrounding “people of color” are not unusual: Panethnicities inherently challenge established social distinctions, and “people of color” is a super-panethnicity. When first introduced in the 1970s, both “Hispanic” and “Asian American” met opposition. Cubans resisted being grouped with Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans (Mora Reference Mora2014); Chinese, Japanese, and others with origins in Asia did not see themselves as members of a common group (Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014). These sources of resistance presented a challenge to community leaders who sought wider alliances. Panethnicity, as Dina G. Okamoto and G. Cristina Mora (Reference Okamoto and Mora2014) argue, is “characterized by a unique tension inherent in maintaining subgroup distinctions while generating a broader sense of solidarity” (p. 219).

This tension has been central to the continuing controversies over the category “people of color.” Black intellectuals and activists, as well as other progressives, brought back the term in the process of generalizing Black experiences of racism and exploitation to other racial minorities and building inter-ethnic coalitions. In this respect, the re-introduction of “people of color” is an example of what Michael Omi and Howard Winant (Reference Omi and Winant2014 [1994]) call a “racial project,” an effort, as they conceive it, to interpret and explain “racial identities and meanings” and “to reorganize and redistribute resources (economic, political, cultural) along particular racial lines” (p. 125). In an era of racially polarized political divisions, it is not surprising that the adoption of “people of color” has come along lines that are ideological as well as racial. But, like other panethnic categories, “people of color” has also met opposition from within, as some members of minority communities—notably Black activists during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests—have objected that it erases critical differences (see, e.g., Code Switch 2020; Edwards and McKinney, Reference Edwards and McKinney2020; Sensei Reference Sensei2019; and for a Hispanic dissent, Falcon Reference Falcon2018). The spread of the alternative term “BIPOC” (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) also reflected a wave of second thoughts by those who saw “people of color” as insufficiently specific (Grady Reference Grady2020).

Changes in racial categories often indicate, and sometimes help generate, changes in social structure, identity, and politics. Writing about whiteness, Matthew Frye Jacobson (Reference Jacobson2003) notes: “Racial categories themselves—their vicissitudes and the contests over them—reflect the competing notions of history, peoplehood, and collective destiny by which power has been organized and contested on the American scene” (p. 9). Like other social categories, ethnic and racial categories embody beliefs about the world that can emerge from different origins and follow different trajectories. While identities internally generated within a group may become entrenched in law and statistics, the traffic goes in both directions: Externally imposed categories, including those of governmental and scientific authorities, may also become incorporated in personal identities (Jenkins Reference Jenkins1994). Categories migrate from one society to another, especially with flows of people (Roth Reference Roth2012). Social movements also originate new categories and new names and meanings for old categories. Both migrations and social movements have been particularly important in the historical travels of the category “people of color.”

Whether categories spread and become entrenched depends critically on the success or failure of political actors in establishing claims framed around those categories (Starr Reference Starr1992). The concept of race itself was not conceived in scientific innocence; its history is inextricably linked to claims of white supremacy. Dorothy Roberts (Reference Roberts2011) is surely correct when she writes, “Race applied to human beings is a political division: it is a system of governing people that classifies them into a social hierarchy based on invented biological demarcations” (p. xi). But race is also a field of political struggle, and in a world where demarcations are inescapable, those who are fighting white supremacy invent demarcations of their own.

In the case of “people of color,” the demarcations bridge nonwhite groups, suggesting commonality across racial lines and a potentially shared identity. To be sure, other labels might serve this purpose; the British, for example, use BAME for “Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic” (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2020). “People of color” has emerged from different historical origins in the Americas and is unusual in that it has had two lives in the United States. This article is about those two lives and the continuities that connect them. The first section asks how the category “people of color” first emerged in the late 1700s and why it declined; the second section discusses how it was re-introduced in the late twentieth century and why has it spread. Text data serve as a means of tracking these changes. Much discussion in recent years has revolved around demographic projections of the United States as a “majority-minority society,” that is, a society with a majority of people of color. Contrary to much of that speculation, however, the future racial order does not depend only on demography; it also depends on the historically shifting ways in which people are classified and identify themselves and, more particularly, on whether the traditional color line becomes a people-of-color line.

The Rise and Fall of “People of Color,” Revolutionary Era to Reconstruction

The term “people of color,” along with variations such as “persons of color,” first appeared in scattered uses in the late 1700s. As Figure 1 shows, it peaked between 1820 and 1850, declined as the Civil War approached, and then virtually disappeared before re-emerging in the late twentieth century.Footnote 2 The early rise and fall in usage were linked to changes in social structure, particularly to the changing situation of free people of African descent in the tripartite racial order that prevailed in the Caribbean and areas in the Lower South of what became the United States.

Fig. 1. Uses of POC terms per million words. “POC” search terms: people/peoples/person/persons of color/colour.

Source: Corpus of Historical American English.

In the Caribbean, three castes—free whites, enslaved Blacks, and free people of color—developed out of the flows of people from Europe and Africa. A mixed-race population originated chiefly from the sexual impositions of European men on the enslaved African and Indigenous women under their power (Garrigus Reference Garrigus2006; Lachance Reference Lachance1994). Some of the men developed long-term unions with enslaved women and emancipated them and their children; a few left them substantial property. The number of free people of African descent also increased through self-purchase by the enslaved, marriages with free spouses, and freedom suits (de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020). Some free people of color were therefore of exclusively African descent, though most were mixed-race (referred to, in the language of the time, as “mulattoes” and by other terms, according to gradations of ancestry or phenotype). By the mid-eighteenth century, free people of color in the Caribbean formed substantial communities, many of whose members acquired education, skilled trades, and property. Some became slaveholders themselves. “People of color” was thus not a synonym for “mulatto,” since most mulattoes were enslaved, and some free people of color were solely African-descended.

In Saint-Domingue (later Haiti) and other French colonies, this intermediate stratum became known as gens de couleur libres (free people of color) during the mid-1700s. Often shortened to gens de couleur (with libres ambiguously implied), this was a legal classification. Although the term appeared in French colonial laws as early as 1712, it began to be used more frequently by jurists in the 1740s and became routine by the late 1760s (Garrigus Reference Garrigus2021; Moreau de Saint-Méry 1784-Reference de Saint-Méry and Élie1790).Footnote 3 The gens de couleur libres and their counterparts in other European colonies with large enslaved populations were able to maintain their position in large part because of the support they provided the regimes, forming a major part of the militia, while also overseeing plantations and performing skilled trades (Garrigus Reference Garrigus2006).

But in Saint-Domingue—the largest of the French colonies—the growing numbers and wealth of the gens de couleur generated resentment from whites. In the 1760s, French colonial elites began to unite whites against the gens de couleur with new racist measures, excluding them from public places and occupations and forcing them to adopt African names (Garrigus Reference Garrigus2006). These apartheid-like efforts to degrade their status, however, aroused a growing group consciousness among them and prompted several of their leaders in the 1780s to go to France in an effort to restore their rights that proved only partially successful (Geggus Reference Geggus2002). In the 1790s the gens de couleur played a critical role in igniting the Haitian Revolution.

In contrast to the Caribbean pattern, Britain’s mainland slave colonies generally developed into two-caste societies. While colonization under British rule also gave rise to race mixing, several factors limited the size and power of a free population of African descent. Not only did colonial authorities prohibit and punish interracial sex; the sex ratios among whites also became more evenly balanced earlier than in the Caribbean, contributing to a decline in interracial unions by the early 1700s. The access of enslaved persons to manumission and self-purchase was also more tightly regulated. What British colonists did not do was first to allow the growth of large mixed-race communities with extensive rights, property, and an armed militia and then to impose a new restrictive regime on them that provoked collective consciousness and resistance. That was the sequence that produced the gens de couleur libres; nothing like it unfolded in Britain’s mainland colonies, although some areas of the Lower South had affinities with the Caribbean pattern. In 1790, when the first U.S. census distinguished among free whites, slaves, and “all other free persons,” it counted only 59,150 in the latter category, just 1.5 percent of a population of nearly four million (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1793).

The term “people of color” entered into American usage through two routes: through reports from the Caribbean and France about the gens de couleur, and through cities in the Lower South with deep Caribbean connections.

The first mentions of “gens de couleur” or “people of color” in the American press originated from the Caribbean in the late 1770s and 1780s—for example, a report from Guadeloupe in the Connecticut Journal (June 10, 1778) and another in the Pennsylvania Packet from Martinique (January 1, 1782).Footnote 4 The English “people of color” seems to have been a direct translation of the French. In 1794, a Philadelphia newspaper, The American Star, republished news from Saint-Domingue in both the original French and an English translation: Where the French said “mulâtres,” the English said “mulattoes” and where the French said “gens de couleur,” the English said “people of colour.” Thomas Jefferson’s correspondence between 1789 and 1791 also illustrates the passage of the French “gens de couleur” to the English “people of color” (Boyd Reference Boyd1958, p. 536; Cullen Reference Cullen1986, p. 11).

Despite the general U.S. pattern, Charleston, SC and New Orleans, LA originally developed under the influence of the same forces that produced a three-caste system in the Caribbean. South Carolina’s original leadership and many of its white settlers came from Barbados and brought with them a harsh slave regime that, unlike other mainland British colonies, had a Black-majority population and prolonged tolerance for miscegenation, resulting in the development of a free, intermediate mixed-race stratum whom white slaveholders considered useful allies in maintaining domination. Louisiana during the eighteenth century was alternately controlled by the French and Spanish, who reproduced in it the same racial regime they created in their Caribbean possessions. The population of free people of color grew especially under Spanish rule (1763-1802), primarily because the Spanish introduced coartación, a customary right enabling enslaved people to purchase their own freedom over their owners’ objections (Ingersoll Reference Ingersoll1991). Beginning in the 1790s, the revolution in Saint-Domingue set off a migration of refugees to other islands in the Caribbean and ports in the United States. In 1809, Cuba expelled a large group of gens de couleur who had settled there. Arriving in New Orleans, they tripled the number of free people of color to about 5000—nearly one-third of the city’s population—strengthening the tripartite racial order (Spear Reference Spear2009).

Charleston and New Orleans reflected influences of both class and race that affected the social position of free people of color in the Lower South. To the north, the mixed-race population in the 1600s and early 1700s originated chiefly from unions of indentured white servants and enslaved Blacks and had little access to education or property (Williamson Reference Williamson1980). By the mid-1800s, more free people of African descent lived in Virginia and other states in the Upper South, where restrictions on manumission were temporarily loosened after the Revolution. The Lower South did not see a comparable relaxation, so the overall numbers of free people of color remained small. But a significant number of them had wealthy white fathers who acknowledged them as their natural children, emancipated them, and left them property (Williamson Reference Williamson1980). Leading members of their community had come from Saint-Domingue and were generations removed from slavery. These aspects of South Carolina’s and Louisiana’s development may help explain why the term “people of color,” with its Caribbean associations, belonged primarily to the Lower South, where it was used chiefly for mixed-race people (Berlin Reference Berlin1976). As a writer in the Charleston Mercury explained in 1823, “The term ‘person of color’ is a term of as settled significance and import as any to be found in our laws, or in common parlance. It is a term in general use all over the West Indies, and is never applied to any person but those of mixed blood and who are descended from negroes” (Berlin Reference Berlin1974, p. 180). Despite the writer’s confident definition, some uses of the term in his own state included Native Americans and those of mixed white-Indigenous ancestry.

When Louisiana became part of the United States in 1803, the U.S. general taking possession of the territory wrote that “the People of Color are all armed” and posed a threat of violence (de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020, p. 80). But the gens de couleur succeeded in reassuring the new government; in 1811 their militia helped suppress a slave revolt and later fought in Andrew Jackson’s victory in the Battle of New Orleans. Whites in South Carolina had similar anxieties about free people of color, particularly after the discovery in 1822 of an insurrectionist plot in Charleston organized by a freedman, Denmark Vesey. An investigating commission concluded, however, that the free people of color were “a barrier between our own color and that of the black—and, in cases of insurrection, are more likely to enlist themselves under the banner of the whites” (Williamson Reference Williamson1980, p. 18).

But while maintaining their status, the free people of color in Louisiana and South Carolina by no means achieved equality with whites. Under U.S. rule, Louisiana lawmakers denied free people of color the rights to vote and sit on juries and ended coartación. Even so, as Alejandro de la Fuente and Ariela J. Gross (Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020) write, “Communities of free people of color peaked in population and power in the first decades of the nineteenth century” (p. 130). Following the influx from Saint-Domingue in 1809, the gens de couleur in New Orleans continued to increase in population for the next two decades and to enjoy economic opportunity and personal freedom.

This was the context for a distinctive legal understanding of the category “people of color.” The 1808 Louisiana Civil Code, still influenced by legacies of French and Spanish rule, recognized “people of color” as a separate social category from enslaved Blacks and free whites; it banned marriages across two social boundaries: between the enslaved and the free and between “free white persons” and “free persons of color” (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1986, p. 25). In Adéle v. Beauregard, a freedom suit by a woman of color in 1810, the Louisiana Supreme Court distinguished “persons of color” from “negroes” and held that while “negroes” were presumed enslaved, “persons of color” enjoyed the presumption of being free. “Persons of color,” the court declared, “may be descended from Indians on both sides, from a white parent, or mulatto parents in possession of their freedom” (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1986, pp. 25-26; Adéle v. Beauregard 1810).

Louisiana, however, was not immune from attacks that took place across the South on the rights of free people of color in the 1830s after Nat Turner’s Rebellion and again in the 1850s. These attacks resulted in restrictions on all those of African descent. Fearing that free people of color would join the enslaved in an insurrection, the white authorities sought to minimize the size of the free population by making manumission nearly impossible, prohibiting in-migration of free people of color, and supporting colonization efforts to “remove” free people of color to Africa. In 1830, Louisiana required free people of color to register; in 1834 it disbanded the community’s militia; and in the two following decades, it did away with many other institutions of theirs (de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020). An increasing white population in New Orleans displaced the gens de couleur from economic niches where they had flourished. Faced with rising hostility, many of them left for France and Haiti, reducing the community from a peak of 15,000 people in 1840 to under 10,000 a decade later (Spear Reference Spear2009). By 1860, the South, including Louisiana, “had committed itself, economically and politically, to slavery … and to the elimination of free people of color as a class” (de la Fuente and Gross, Reference de la Fuente and Gross2020, p. 157).

Although antebellum Louisiana is a special case, its laws and social practices—like those of South Carolina—illustrate one of the two general alternative conceptions of “people of color” during the era of slavery. As I suggested at the outset, “people of color” could be used either in an intermediate sense or as an umbrella term. The intermediate sense was implicit in much usage in the Lower South. South Carolina law, for example, declared, “Free negroes, and free persons of color (meaning of course mulattoes and mestizoes) are prohibited (unless they have a ticket from their guardian) from carrying any fire arms” (Oneall Reference O’Neall1848, p. 16, italics added). This was also the sense in which it was long used in Louisiana, as the court in Adéle v. Beauregard made clear when it distinguished “persons of color” from “negroes.” Louisiana law throughout the nineteenth century treated Indians as people of color (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1986). In 1860, the city of Charleston included thirteen Indians among the 371 free persons of color it listed as taxpayers (Frazier Reference Frazier1957).

This intermediate usage was “intermediate” in two respects. It conceptualized people of color as both racially intermediate (between Black and white) and of intermediate legal status (legally free but subject to racial restrictions that barred them from the full rights of citizenship). In South Carolina and Louisiana, free people of color did include some with exclusively Black ancestry as well as Indians, but the prototypical members of the category were of mixed Black-white and Black-Indian descent.

Outside of the Lower South, “people of color” came to be used in a second sense—one that has a more direct connection with its meaning today. It came to be used as an umbrella category for all non-whites, chiefly Black people. In the early republic, many organizations such as churches and schools in the Black community had included “African” in their name, but by the 1830s that choice was being reversed. For example, the African Baptist Church of Boston, established in 1806, became the “First Independent Church of the People of Color” in the 1830s (Rael Reference Rael2002, p. 91). The likely explanation is that leaders in the Black community became concerned that use of “African” could appear to legitimize the efforts of the American Colonization Society, founded in 1816, to send free Blacks to Africa. For a time between the 1820s and 1840s, “people of color” became a preferred self-definition for Black people, at least among their leaders. Meetings called to protest the colonizationist program referred to the participants as “free people of color.” In its inaugural issue in 1827, Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-owned and edited newspaper, announced that it would uphold the interests of “free persons of color.” The attraction of the term “people of color” to the Black leadership was plain: It was “relatively unsullied by the effects of racial prejudice” and had a “respectable history” associated with “African-descended social elites throughout the western hemisphere” (Rael Reference Rael2002, p. 102). Appropriated as a Black collective self-definition, the category “people of color” was not limited to a mixed-race elite, nor did it necessarily embrace Indians. The use of “people of color” as an inclusive term for Black people in the North extended beyond the Black community, as in provisions of New York State’s revised constitution in 1821 (Hirsch Reference Hirsch1931). Abolitionists often used “people of color” as an inclusive term for Black people (see, e.g., Antislavery Convention of American Women 1838). Indians were sometimes included among “people of color,” but often the category’s boundaries were ambiguous.

During the antebellum period, “colored” also had both intermediate and umbrella meanings. From the standpoint of many free people of color in the South, “colored” signified an intermediate racial identity. A study of William Ellison—a mixed-race man in South Carolina who after being emancipated at age twenty-six in 1816 became a cotton gin manufacturer, slaveholder, and patriarch of a family that left behind a trove of personal correspondence—notes:

To Ellison and his friends, a “black” person had no white ancestors and was most likely a slave; a “colored” person was the descendant of white and black ancestors and was more likely than a black person to be free; “Negro” was a collective term that encompassed all persons with any Afro-American ancestry (Johnson and Roark, Reference Johnson and Roark1984, pp. xv-xvi).

Black leaders in the North, however, used “colored” more expansively. When one of the founders of Freedom’s Journal, Samuel Cornish, took over the Weekly Advocate in 1837, he renamed it the Colored American and used “people of color,” “colored people,” and “colored” interchangeably in its pages to refer to Black people collectively (Rael Reference Rael2002, p. 102). By the 1840s, references to “colored” in Black newspapers far outstripped references to “people of color.” The same pattern is evident from the series of regional and national gatherings that are now called the “colored convention movement.” During the 1830s, these conventions styled themselves as meetings of “free people of color,” before switching in the 1840s and later to terms such as “colored citizens” and “colored people.” The use of “colored” did not necessarily imply a repudiation of the term “people of color,” which as the minutes of the meetings show, the convention participants continued to use, albeit not as frequently (Colored Convention Project Digital Records n.d.). Although historians have made little of the shift from “people of color” to “colored,” it may have subsequently exposed “colored” during Jim Crow to the accumulation of derogatory associations that “people of color” escaped—allowing the latter to be revived a century later, free of racist overtones.

Why did usage of the term “people of color” virtually disappear after the mid-1800s? Structural change in former slave societies and language change elsewhere were both involved. In the antebellum South, “people of color” had primarily referred to “free people of color,” a sociolegal category that disappeared with slavery’s abolition. During Reconstruction, the former free people of color sought to identify themselves with the freedmen and become leaders of the entire Black community; a separate group identity, which had already been eroding before the Civil War, no longer made any sense. Later, the triumph of the one-drop rule tended to collapse the old distinctions that many mixed-race people had earlier sought to maintain. In the North, language change—the shortening of “people of color” to “colored”—better accounts for the shift, though “colored” lost the cross-racial significance of “people of color.” If the colored convention movement and Black newspapers are any indication, Black people were already mainly using “colored” as a collective self-description by the 1840s. “Colored” remained the favored term among the community’s leadership until the late nineteenth century, when “Negro” began to gain traction (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2021; Smith Reference Smith1992).

Louisiana, the area where “people of color” had its widest usage, was a special case. The New Orleans “creoles of color” remained a distinct group long after the Civil War (Gehman Reference Gehman1994). In Charleston and elsewhere, an elite of light-skinned Blacks had their own separate churches and private associations such as Charleston’s Brown Fellowship Society (Gatewood Reference Gatewood2000). But while colorism remained—indeed, remains (Monk Reference Monk2014)—an intermediate racial group did not become a fixture in American society. During the nineteenth century, race theorists who sought to prove that race mixing led to debility helped perpetuate the use of “mulatto” in the Census (Nobles Reference Nobles2000). Within the Black community, the Jamaica-born Marcus Garvey tried in the 1920s to revive the distinction between Blacks and mulattoes to strengthen Black pride (Davis Reference Davis1991). But neither succeeded. In 1931, the Black sociologist Horace Mann Bond argued that no mixed-race stratum had taken a durable form in the United States for two reasons: the passing into white society of those able and wanting to do so, and “the unyielding refusal” of whites to accommodate mulattoes: “There is here no widespread wasting of energies or efforts on the creation and maintenance of an intermediate group” (Bond Reference Bond1931, p. 554). The year before, the term “mulatto” had disappeared from the decennial census, testimony to the adoption of the one-drop rule by the federal government.

In New Orleans, “creoles of color” has lingered on as an identity, although younger people in the community during the Civil Rights Era rejected it and began calling themselves Black, erasing a distinction that earlier generations had preserved (Dominguez Reference Dominguez1986). With that shift, the old intermediate meaning of “people of color” lost its powerful hold in its strongest redoubt. But while the Civil Rights Era effectively closed one phase in the history of “people of color,” it opened another.

“People of Color” Reborn

When the category “people of color” was revived in the late twentieth century, it took on an enlarged scope and significance. In the nineteenth century, “people of color” had not generally included individuals with origins in Asia or Mexico, even though Chinese and Japanese immigrants came to the West Coast, and Mexicans lived in the Southwest.Footnote 5 Dispersed in regional enclaves, they did not affiliate organizationally with one another or with Blacks and Indigenous people, and whites did not see them as members of one collective group. The revived use of “people of color” since the 1970s reflects a changed society where many people both within and outside these groups have seen them as sufficiently similar to justify referring to them collectively.

As different as the old and new meanings of “people of color” are, they have underlying continuities. Both have emerged in response to the mixing of peoples and served as a bridging identity for racial groups excluded by whites. Both have responded to immigration. In both its antebellum and contemporary uses, “people of color” has been a term of respect rather than a term of abuse. Originally, people of color were associated with freedom. Since the 1970s, the term has not only served as a collective identity for groups previously treated as residual “non-whites” or “minorities”; it has also signaled a re-imagining of their status—and their numbers as a potential voting bloc—on a co-equal plane with whites.

Although ethnoracial categories often emerge slowly, governmental policy decisions and concerted group action at distinct historical moments may matter a great deal. The same critical agents—the state, political activists, and media organizations—that Mora (Reference Mora2014) identifies in a study of the rise of Hispanic panethnicity had important roles in the re-introduction and diffusion of the category “people of color” in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. That process may be thought of as taking place in four stages:

1. the advent in the 1960s and 1970s of a new configuration of “minorities” through the federal government’s civil rights and statistical policies;

2. the adoption of the term “people of color” as a collective identity for those minorities, initially by Black, progressive, and feminist activists in the 1970s;

3. the polarized diffusion of “people of color” into the general media during subsequent decades; and

4. finally, the recent emergence of second thoughts among activists about the term “people of color” as insufficiently specific.

Just as the meaning of “people of color” evolved as it moved out of the Lower South during the early 1800s, so “people of color” has evolved since the 1970s. Much of the early, radical use conceived of “people of color” in an anti-colonialist sense as people who suffer racial oppression, and that understanding has not wholly disappeared. But as the term has become more widely adopted in the general media, it has come to serve more as a conventional, anodyne synonym for non-whites. Yet at least in some minds, the connotations dating from the 1970s raise doubts as to whether some non-whites, such as relatively privileged Asians, genuinely belong in the category.

The State and the Configuration of “Minorities” as a New Super-panethnic Grouping

During the mid-twentieth century, “minorities” in the United States came to mean racial minorities and specifically to include Blacks, Hispanics, Asian Americans, and American Indians. This configuration did not automatically flow from historical experience. The United States had treated Blacks in fundamentally different ways from other minorities, most clearly under slavery and Jim Crow. It dealt with Native American tribes, unlike any other groups, as “domestic dependent nations.” During the eras of slavery and segregation, Mexican Americans and other Spanish-speaking people insisted they were entitled to be treated as white. Immigrants from Asia were divided among themselves by persistent hostilities (Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014).

The new configuration of minorities that emerged in the mid-twentieth century required a break with historical barriers to shared panethnic identities and the advent of new assumptions about the essential likeness of all four minorities on the basis of being historically stigmatized. Until the 1960s, Blacks were a caste apart, and other minorities resisted being linked to them; by the mid-1970s, representatives of the other minorities sought inclusion in programs developed initially with Blacks in mind. This movement toward equating the other three ethnoracial groups with Blacks was the precondition for the new conception of “people of color”—the basis of a people-of-color equation. Unlike “Hispanic” and “Asian American,” the category “people of color” did not become an official legal or statistical classification. But by recognizing the three other minority groups as suffering analogous injuries and deserving the same legal guarantees, the government provided the foundation for the re-emergence of “people of color” as a social category.

During the post-World War II era, minority rights became a global as well as a domestic concern. The Nazis’ persecution of the Jews and other minorities had brought international attention to racism and discredited its open expression; now, in the Cold War, the United States found itself on the defensive because of its own racist practices, particularly as it competed with the Soviet Union for support in what was then called the “Third World.” As a result, civil rights for Blacks became a national-security issue, and the Civil Rights Movement acquired more political leverage (Dudziak Reference Dudziak2011 [2000]; Skrentny Reference Skrentny2002). The changed postwar environment also discredited the racist national-origins quotas in immigration laws, from which the government was already making exceptions so as to admit refugees from Communist countries such as Cuba. The Immigration Act of 1965 eliminated the old quotas.

The major advances in legislative protections of minority rights took place between the mid-1960s and early 1970s, the period from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. Standard accounts typically see the expansion of rights as a response, indeed, a concession to pressure from mobilized social movements and shifts in public opinion. That explanation applies well enough to the adoption of legislative protections for Blacks. Equal rights for Black people were nearly the entire focus of the protests and public discussion that led up to the passage of civil rights legislation. From 1940 to 1972, The New York Times reported on almost 3800 civil rights demonstrations, more than ninety-five percent of which concerned discrimination against Blacks (Burstein Reference Burstein1998).

But what the legislation achieved for Blacks it did not achieve for them alone. The civil rights laws generally prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, and sex. Although the government might have focused on other kinds of discrimination, it primarily used its authority in the late 1960s and 1970s to identify other groups in addition to Blacks subject to racial discrimination. This was the period when agencies such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission designated the minorities relevant to civil rights protection and created the reporting forms and policy tools for dealing with minority underrepresentation (Skrentny Reference Skrentny2002). A directive from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in 1977 consolidated the racial classifications to be used in federal programs (Nobles Reference Nobles2000). Although the ostensible purpose was only uniformity in federal data collection, the categories that the government established and the data it collected had far-reaching effects on racial classification in popular understanding, the social sciences, and private as well as governmental institutions.

For example, the original trial OMB directive classified people with origins in both India and the Middle East as white, leading to lobbying campaigns by representatives of both groups for reclassification as minorities (Nobles Reference Nobles2000). The OMB decided to reclassify only those from India as Asian Americans, a bureaucratic decision that has firmly categorized South Asians as a racial minority but created legal barriers to discrimination claims by Americans with Middle Eastern or North African origins and ambiguity as to whether they count as “people of color.”

From “Minorities” to “People of Color”: The Activists’ Role

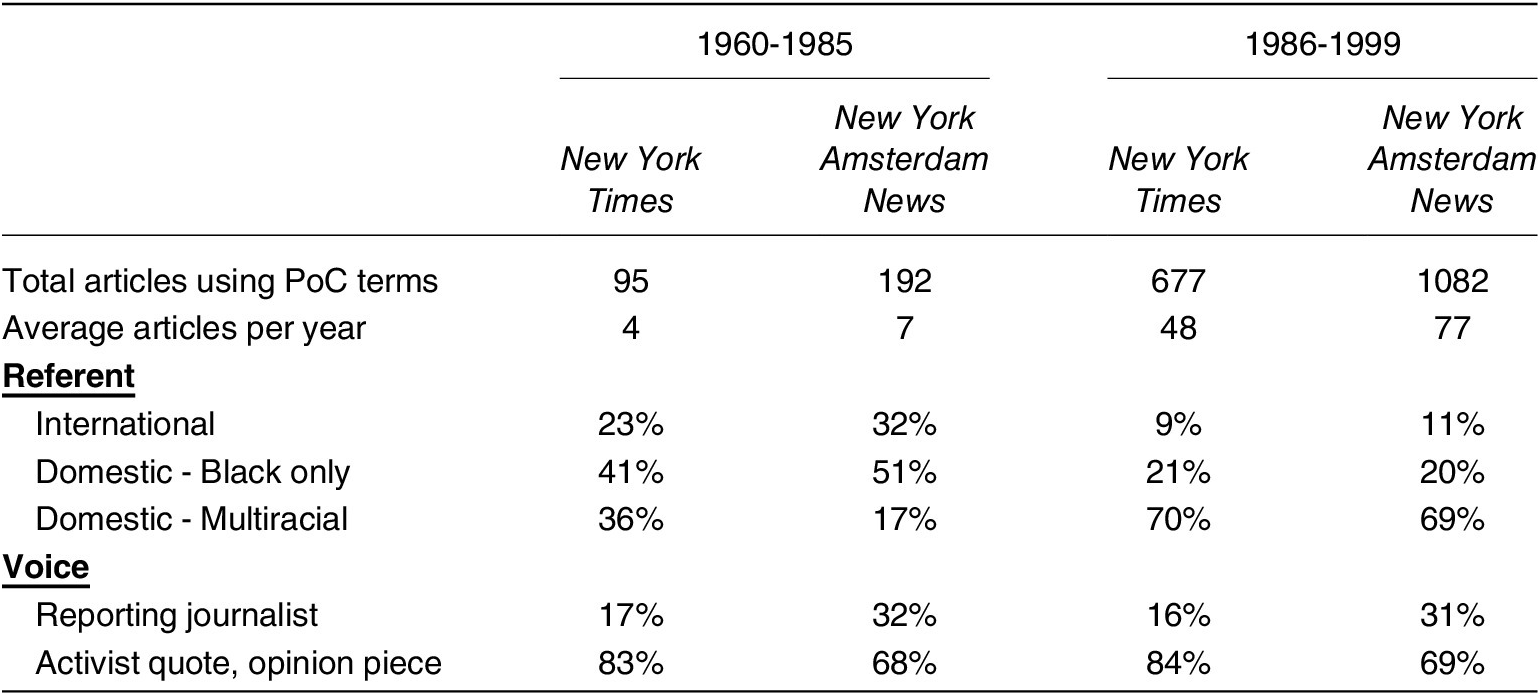

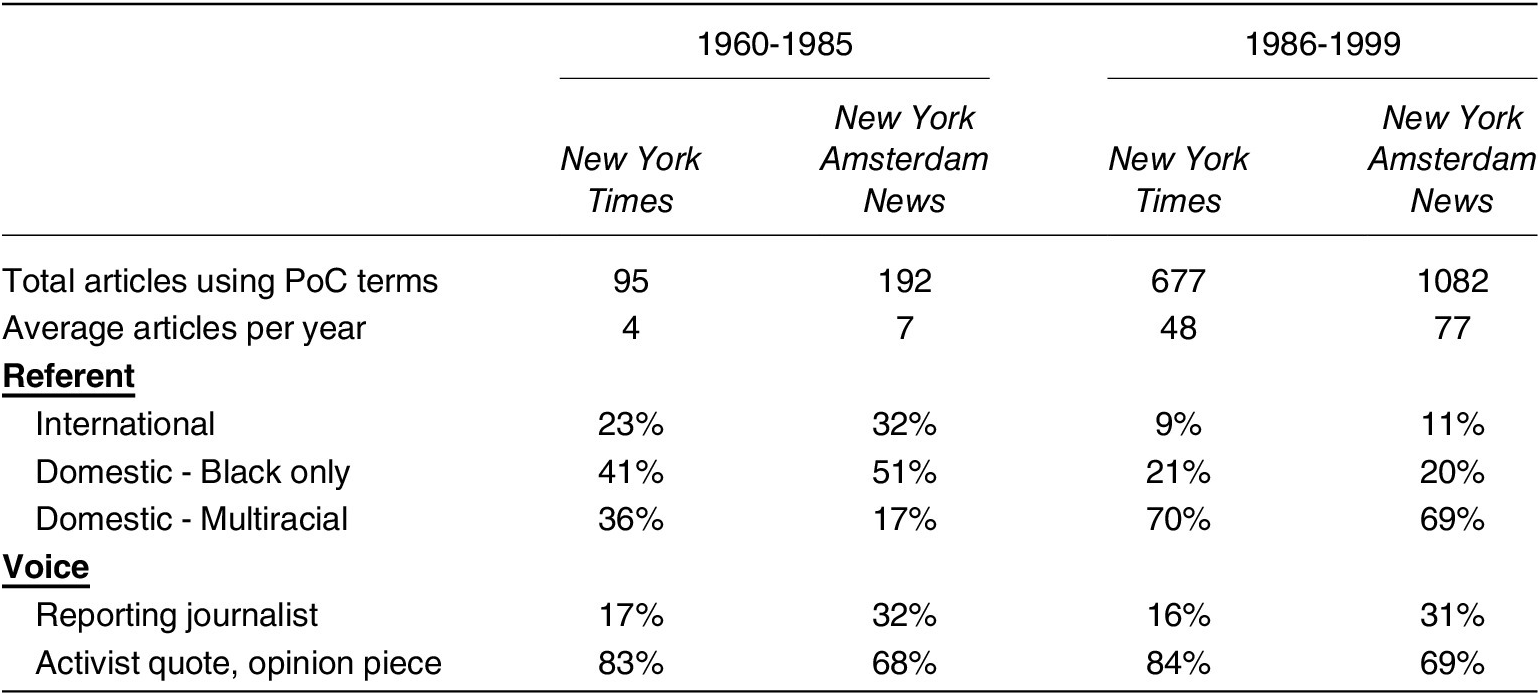

The category “people of color” slowly began making a comeback in the late twentieth century. Terms like it had never entirely disappeared. In his speech at the March on Washington in August 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke of “citizens of color,” but he was referring in that context to Black people alone. As Table 1 shows, from 1960 to 1985, “people of color” and related terms appeared infrequently in the media—only in the single digits per year on average in both The New York Times and the leading black newspaper in New York, The Amsterdam News. In The Amsterdam News, half the references were to Blacks domestically, a third to non-white peoples internationally, and only about one-sixth to domestic racial minorities collectively. In both newspapers, most of these uses came in quoting activists or in opinion pieces, not in a reporter’s voice.Footnote 6

Table 1. Usage of POC terms in two New York newspapers, 1960-1999.

Search terms: “people of color”; “person of color”; “persons of color.”

The phrase “people of color” was especially favored by the more radical and militant. In 1970, the platform of the Black Panther Party referred to “people of color” in affirming a commitment to international solidarity: “We will not fight and kill other people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government of America” (Black Panther Party Reference Party1970). “People of color” also began showing up in domestic discussions of interracial solidarity. In 1972, speaking to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Angela Davis declared that although “Black unity” should come first, “we must move to make alliances with other poor and working people of color” (quoted in Milwaukee Star 1972; see also Davis Reference Davis1974, p. 199). “People of color” fit readily into a political vocabulary that used colors as shorthand for racial groups. A writer in a Black Milwaukee newspaper in 1974, for example, referred to demands for jobs by “Black, brown, red, and other people of color” (Crosby Reference Crosby1974). The embrace of color symbolism was pervasive in militant movements of the era; the Black Power movement became a template for parallel movements calling for Red Power, Brown Power, and Yellow Power.

In the heyday of the militant ethnic-consciousness movements, “Third World” was more common as an umbrella term than “people of color,” though both were used. College campuses had Third World student organizations and Third World centers. For many radicals, Third World groups replaced the working class as the protagonist of revolutionary hopes (Yuen Reference Yuen1997). But during the late 1970s and 1980s, the label “Third World” fell into disfavor, probably because of its association with revolutionary movements abroad that by then had come to be seen as romantic or irrelevant in the U.S. context (Yuen Reference Yuen1997). So, in a sense, with its less overtly anti-colonialist intent, “people of color” fully assumed the place that “Third World” had partly occupied in the vocabulary of the American left. Reflecting on her experience in the late 1990s, a Korean American, E. Tammy Kim, writes, “In student organizing as well as immigrant-rights work, housing campaigns, and the labor movement, ‘people of color’ and the more revolutionary ‘women of color’ helped define a united front against those in power—who were almost invariably white and male, whether boss or landlord, provost or governor” (Kim Reference Kim2020).

The term “women of color” first gained the national spotlight in November 1977 at the federally sponsored National Women’s Conference in Houston, where a delegation originally calling for a “Black Women’s Agenda” attracted support from other minority women for an expanded resolution on the “double discrimination” faced by “women of color.” The resolution was read in five parts on the convention floor by a Black woman, a Native American, a Japanese American, a Puerto Rican, and finally Coretta Scott King (Perlstein Reference Perlstein2020). According to the Black feminist Loretta Ross, the focus on “women of color” was an expression of solidarity, “a commitment to work in collaboration with other oppressed women of color” (Ross Reference Ross2011). Radical minority women made the implicit bias of white-dominated feminism a major target. “We women of color,” wrote the editors of a 1981 anthology, “are the veterans of a class and color war that is still escalating in the feminist movement. … Racism affects all our lives, but it is only white women who can ‘afford’ to remain oblivious to these effects. The rest of us have had it breathing or bleeding down our necks” (Anzaldúa and Moraga, Reference Anzaldúa and Moraga1983, pp. 57, 58).

Activists often play a cultural as well as political role in reframing both the everyday and official categories of social life. The introduction of the terms “Hispanic” and “Asian American” and the re-introduction of “people of color” and “women of color” were part of an ethnoracial reframing of American society. Aggregating minorities first into panethnic groups and then into the super-panethnic category “people of color” had a cultural and political logic. The formation of larger ethnic blocs gives them “more weight in playing ethnic politics at the higher level” (Van den Berghe Reference den Berghe1981, p. 256). Blacks, Native Americans, Hispanics, Asian Americans—all of these racial blocs assemble what might otherwise be smaller fractions into more powerful wholes. Identification as “people of color” was one step further in the push toward enlargement necessary for greater cultural visibility and political power.

Polarized Diffusion: The Role of the Media

Reborn in the Black, progressive, and feminist movements, “people of color” carried ideological overtones and only gradually penetrated mainstream journalism. A controversy in 1988 put the term at the center of a characteristic culture-war dispute of the era. In a New York Times op-ed, Jacob Neusner (Reference Neusner1988), a neoconservative on the board of the National Endowment for Arts, wrote that a representative of a nongovernmental group, the Assembly of American Cultures, had told the NEA’s board that only “people of color” were authentically American. Neusner foresaw a time when “the ideologues of ‘people of color’” would delegitimize “’white culture’” as “un-American.” Three weeks later, the Times published a correction, saying that a review of the transcript of the meeting showed Neusner’s claims about it were “substantially inaccurate” (Hodsoll Reference Hodsoll1988).

Following up on this episode, the Times’s language guru, William Safire (Reference Safire1988), devoted a column to the phrase “people of color,” which he noted was controversial but “has never been more in vogue.” Although Safire was a Republican, he seemed unperturbed. “When used by whites,” he wrote, “‘people of color’ usually carries a friendly and respectful connotation, but should not be used as a synonym for ‘black’; it refers to all racial groups that are not white.” As that explanation indicates, Safire did not feel he could assume that readers knew what “people of color” meant. His own newspaper rarely used the term; for all of 1988, “people of color,” “person of color,” and “persons of color” appeared in a total of only seventeen articles.

But the late 1980s and early 1990s did see an increase in usage in the Black press and to a lesser extent in the Times. By this time, “people of color” was used predominantly to mean racial minorities in general rather than Blacks alone, though it still had not been integrated into journalists’ reporting vocabulary (see Table 1). The increase in usage may reflect political shifts. During the late 1980s, coalitions of Blacks and Hispanics had emerged in mayoral elections in Chicago, New York, and other cities, and in 1988 Jesse Jackson had organized a campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination around a “Rainbow Coalition.” But the moment was short-lived. By the mid-1990s, the urban Black-Hispanic coalitions had suffered substantial reverses as a result of Hispanic defections (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2011). Stories using “people of color” tailed off in The Amsterdam News and remained relatively low in The New York Times into the early 2000s.

“People of color” diffused more widely into the media during the decade beginning in 2011. For the period from January 1, 2011 to July 1, 2021, I used Media CloudFootnote 7 to track U.S. news media usage of “people of color” (POC) and related terms. As Figures 2 and 3 show, POC terms increased in the run-up to the 2016 election, climbed substantially during the Trump presidency, and jumped to a sharp peak in spring 2020 during the Black Lives Matter protests following George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020.

Fig. 2. Percentage of stories with POC terms – Top newspapers versus top digital native media.

Source: Media Cloud queries for people/person/persons/communities/women/men of color.

Fig. 3. Percentage of stories with POC terms – Liberal versus conservative media.

Source: Media Cloud queries for people/person/persons/communities/women/men of color

Two clear patterns emerge from the data. First, from 2011 until mid-way through 2019, stories using POC terms were twice as frequent in top digital native news sitesFootnote 8 as in top newspapers, but by 2020, usage in those sources had converged (Figure 2). At least for a time in 2021 top newspapers used POC terms more often.

In addition, usage of POC terms was higher in liberal than in conservative news sourcesFootnote 9—a gap that grew from 2011 to 2021 (Figure 3). When POC terms came up on right-wing news sites, moreover, they were often used sarcastically or in quotations from liberal sources intended to show the folly of those views. This is consistent with the pattern in Congress, where from 1993 to 2018 Democrats accounted for seventy percent of the uses of “people of color” in legislation, committee reports, and floor debates (Pérez Reference Pérez2021). These ideological and partisan differences in usage likely reflect the continuing implication that people of color suffer oppression and discrimination—an implication that conservatives in the media and Republicans in Congress have not been willing to grant.

As the 2020s began, mainstream journalism had fully integrated “people of color” into its vocabulary; indeed, Media Cloud data show that by 2020 top news sources were as likely to use “people of color” terms as news sources favored by the left. The rising number of stories with POC terms reflected not only greater attention to racial issues but also a change in media practice. Where journalists previously said “minorities” or “non-whites,” they were now more likely to say “people of color.” In top news sources (both top newspapers and native digital), according to data from Media Cloud, the word “minorities” had been two and a half times more common than “people of color” from 2011 through 2019, but in 2020 “people of color” was fifty-five percent more frequent. The “of color” vocabulary expanded, with the addition of phrases such as “voters of color” that mainstream journalism had largely avoided. From 2011 to 2018, the ratio of usage of “minority voters” to “voters of color” was 9.9 to 1. But by 2019, the ratio was only 1.6 to 1, and by 2020 “voters of color” was twenty percent more frequent than “minority voters.” This was also the period when major news media decided to capitalize “Black” (Bauder Reference Bauder2020). The shift to “people of color” may have had a similar impetus as a gesture of respect. It was just at this point, however, that progressive activists had second thoughts about the category “people of color.”

Activists’ Second Thoughts

Although conservatives had long disdained the phrase “people of color,” a backlash emerged from a different direction against the term’s growing use in 2020. In a September 2020 National Public Radio program whose title asked “Is it time to say R.I.P. to P.O.C?,” one of the hosts, Shereen Marisol Meraji, said: “I’ve personally been using the term people of color since the mid-’90s…. But after the protest for Black lives reignited this past spring, I saw a lot of people online saying they were over it.” To which her co-host Gene Demby responded: “Black folks in particular. I saw a lot of people saying, just please call me Black” (Code Switch 2020).

Criticism of the term had been percolating for several years. In a 2018 essay, a Black journalist, Joshua Adams, wrote, “Describing myself as ‘POC’ feels like walking into a space with an apology in hand, a preemptive ‘sorry’ for any offense my Blackness may have caused.” Some Black writers gave the argument a sharper edge, insisting that other minorities did not face the racism Blacks confronted but benefited from diversity policies more than Blacks did. In an essay in 2019 (“Don’t Call Me A Person of Color: I’m Black”), Seren Sensei, an activist and prominent YouTuber, argued, “We are not all vaguely ‘persons of color.’ Specificity matters … When POC is used interchangeably with Black, the fact that NBPOC (Non-Black Persons of Color) are directly benefitting from anti-Black racism becomes hidden from view.”

One response to the critique of “people of color” was the adoption of BIPOC, which, according to Media Cloud data, began spreading into the news media in early 2020. The earliest use of BIPOC, according to a New York Times effort to trace the term’s origins on social media, appears to have been as a hashtag in a 2013 tweet by a queer Black woman in Toronto, but it didn’t catch on for years (Garcia Reference Garcia2020). Confusion may have been an obstacle: “On social media, many assumed the term stood for ‘bisexual people of color’” (Garcia Reference Garcia2020). Uncertainty has also surrounded BIPOC’s boundaries: Did it exclusively mean Black and Indigenous people? Activists have generally seen BIPOC only as “centering” Black and Indigenous people, who have endured the singular historical wrongs of enslavement and genocide (Grady Reference Grady2020). But the meaning is not self-evident, and there is no official definition to turn to. For whatever reasons, use of BIPOC has remained limited. During 2020, according to data from Media Cloud, the ratio of use of “people of color” terms to BIPOC was 29 to 1 in top news sources and 20 to 1 even in news sources favored primarily by people on the left.

The debate about BIPOC has accentuated a concern that Asian Americans already had about the use of “people of color.” Anti-Asian violence during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic led an Asian American writer to ask, “Why does nobody care when our people get attacked and killed in the streets? … We are not white, but do we count as ‘people of color’?” (Kang Reference Kang2021, italics added). BIPOC implicitly drops Asians to a secondary position, and the phrase “Black and Brown,” another substitute for “people of color,” leaves out Asians entirely. According to data that Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) presents, while Blacks, Hispanics, and Asian Americans agree that Blacks are the “most prototypical” people of color—that is, best exemplifying the category—they say that, of those three major groups, Asians are the least prototypical. On some occasions, public figures have just seemed to forget that Asian Americans qualify as people of color. In the 2021 race for the Democratic nomination for mayor of New York City, the leading Black candidate, Eric Adams, accused two of his rivals, Andrew Yang and Kathryn Garcia (who is white), of joining forces to prevent “a person of color” from becoming mayor “when this city is overwhelmingly people of color.” After Yang responded that he had been Asian his “entire life,” Adams clarified that he had meant his rivals were trying to stop a “Black or Latino” person from becoming mayor (Fitzsimmons and Mays, Reference Fitzsimmons and Mays2021). The revival of the term “people of color” began as an attempt to affirm a shared identity and common interests, but internal tensions over its scope persist.

Conclusion: From the Color Line to the People-of-Color Line?

The social category “people of color” has been born twice from the mixing of peoples—first from the flows of people from Europe and Africa into North America; then from the additional flows into the United States of Latin Americans and Asians. But to suggest this is a purely demographic phenomenon would be a mistake. How people group and identify themselves, and how they are classified and named by others, are cultural and, perhaps above all, political phenomena.

These cultural and political choices become especially salient in resolving anomalies and ambiguities in a system of racial classification. In the Black-white system of New World slavery, the gens de couleur were an anomaly as free people of African descent. Depending on context, the term “people of color” had two uses. It could serve as a name for an intermediate grouping (legally and racially) or as an umbrella term for people deemed not to be white (in most contexts, Blacks and mixed-race people). Whether states gave members of intermediate racial groups an intermediate legal status, and what kind of rights they afforded them, was a supremely political matter. Where enslaved Black people outnumbered whites as they did in Saint-Domingue, South Carolina, and Louisiana, the master class often regarded free people of color as useful allies and gave them rights denied to their counterparts elsewhere. But when circumstances changed, the regimes subjected them to restrictive rules based on race. The end of slavery and codification of a binary racial system squeezed out an intermediate stratum, diminishing the need for an intermediate category or a collective term to group together those who were not white.

It is not common for a racial term discarded in one era to be revived a century later. Most old terms for subordinated groups have acquired ugly overtones, but “people of color” retained an aura of dignity and respect. Its revival came in stages, as it migrated from progressive, Black, and feminist movements into mainstream journalism and politics between the 1980s and Trump’s presidency. Although some activists had second thoughts by 2020, the progressive effort dating from the 1970s to reimagine “minorities” as “people of color” has had considerable success in creating an affirmative, bridging identity. To be sure, its boundaries are ambiguous and contested, and not all people being identified in the media as “people of color” see themselves in those terms. But, unlike BIPOC, which has not moved into general usage, “people of color” has become a category of everyday social life. Even if the label changes, the growing population of people with complex, mixed-race identities suggests that a common, bridging identity will remain important.

But how important? Hispanics, Asians, and people of mixed-race backgrounds are the swing vote of the emerging racial order. As has been apparent since the 1980s, the United States is moving away from the old binary Black/white world; the critical questions about the future are how the new and growing groups, including multiracials, will be aligned and what impact they will have on traditional racial boundaries. The term “people of color” is associated with a vision of the future that assumes the continued salience of the white/non-white boundary and the common alignment of groups on the non-white side. That assumption has been challenged from more than one direction: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2004) envisions the United States moving toward a “triracial stratification system similar to that of many Latin American and Caribbean nations,” composed of whites at the top, a small intermediate category of “honorary whites” (assimilated Asians and Hispanics), and “a nonwhite group or ‘collective black’ at the bottom” incorporating “most immigrants” (p. 932). George Yancey (Reference Yancey2003) sees the primary line of division as falling along the Black/non-Black boundary. Richard Alba (Reference Alba2020) envisions a diversified “mainstream” as encompassing many people now grouped under “people of color” and potentially becoming more open to Blacks as a result of a blurring of racial boundaries.

U.S. politics since the 1960s has given rise to the new people-of-color configuration, and Donald Trump’s election raised both consciousness and controversy about “people of color” to an unparalleled degree. But whether racial boundaries primarily fall on the old color line or a new people-of-color line is, in principle, unknowable because the structure of the racial order depends on cultural and political processes that cannot simply be extrapolated from recent trends. The politics of immigration will affect both population growth among different ethnoracial groups and whether immigrant ethnicities are replenished or attenuated. Political choices will also determine whether, as the swing vote in the racial order, Hispanics, Asians, and multiracial people align themselves more with Blacks or with whites. It is precisely because race is not a biological phenomenon that politics and culture matter as much as they do in the making and, in this case, revival and remaking of racial categories.

Acknowledgments

I thank Julia Byeon, Fatima Sanogo, and Bailey Ransom for their assistance in the research, and Prof. John Garrigus for an analysis of French colonial law. I also want to thank Richard Alba, Virginia Dominguez, and colleagues at Princeton, as well as two commentators at a public forum, G. Cristina Mora and John McWhorter, for their criticism and suggestions.