Policy Significance Statement

This research shows that even when corruption is routine, people generally think it is wrong. However, people may wrongly believe others in their community are tolerant of certain corrupt behaviors and such mistaken beliefs can undermine efforts to foster collective action against corruption. Individuals are often mistaken about the distribution of personal normative beliefs within their communities (i.e., they hold mistaken beliefs or erroneous normative expectations). This article contributes new evidence of the presence of mistaken beliefs surrounding routine bribery behaviors and highlights how this may make people unaware of the presence of like-minded individuals in their community with whom they may cooperate with against corruption.

1. Introduction

Despite decades of implementation, conventional anti-corruption solutions have not led to a consequential reduction in corruption within contexts where it is seen as prevalent (Menocal and Taxell, Reference Menocal and Taxell2015). This success gap has driven recent shifts in corruption studies away from a concentration on legal (“rule of law”) and institutional approaches to complementary and nuanced approaches that now pay more serious attention to how corrupt practices are contextually understood and reproduced by “those directly engaged in them” (Baez-Camargo, Reference Baez-Camargo2017, p. 3). These newer approaches have sought to understand corrupt practices in relation to local contexts (Haruna, Reference Haruna2003; Kjaer, Reference Kjaer2004; Rugumyamheto, Reference Rugumyamheto2004), by focusing on its informal institutions (Baez-Camargo and Passas, Reference Baez-Camargo and Passas2017); functionality and, the ways in which corruption can be best understood as both a social interaction and classic collective action problem (Olson, Reference Olson1965; Ostrom Reference Ostrom2000; Mungiu-Pippidi, Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2011; Persson et al., Reference Persson, Rothstein and Teorell2013; Marquette and Pfeiffer, Reference Marquette and Peiffer2015).

However, research into how various contextual factors combine with informal rules and behavioral drivers to sustain deeply entrenched corrupt practices is promising but still at a relatively early stage particularly for African contexts. A modest number of qualitative and quantitative studies using behavioral or social norms methodology have begun to uncover and elucidate the types of context-specific drivers which surround and “normalize” specific corrupt practices (e.g., Hoffmann and Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2017; Köbis et al., Reference Köbis, Iragorri-Carter and Starke2018). Such research shows how measuring beliefs and expectations provides helpful insight into the underlying mechanisms of collective behaviors such as corruption. These studies suggest that when different aspects and expectations are varied within a behavior, it becomes more possible to unbundle and therefore, better understand the behavioral qualities of corruption as well as the social considerations, choices, and pressures individuals face when making decisions about corrupt practices (see Köbis et al., Reference Köbis, Iragorri-Carter and Starke2018; Jackson and Köbis, Reference Jackson and Köbis2018, Scharbatke-Church and Chigas, Reference Scharbatke-Church and Chigas2019).

More recent quantitative studies are providing evidence for the role of shared beliefs in the social acceptability of corruption in certain local contexts and the reasons and conditions under which people engage in specific forms of corruption (e.g., Hoffmann and Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2021). These studies show that in some cases, individuals may engage in corrupt practices (such as offering and soliciting bribes) independently of what others think or do which means the practice is not dependent on social beliefs (Hoffmann and Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2021). Perhaps the most obvious case of this is when individuals believe that corrupt behavior helps them satisfy an immediate need or pressing problems, such as when citizens offer bribes to expedite otherwise cumbersome administrative processes, or when public servants solicit bribes to supplement meager public salaries. While one-off payments in situations where cumbersome administrative processes are rare can be avoided, in contexts where cumbersomeness is more common and normalized, bribes through informal arrangements to reduce administrative bottlenecks are very difficult to avoid. Curbing collective practices that are driven by nonsocial expectations such as everyday pressing problems and competition for scarce resources (e.g., school placements, hospital admission, jobs, and government benefits) may often involve changing incentive structures (e.g., overhauling bureaucratic processes and swiftly punishing impunity).

In other cases, however, individuals may engage in bribery behavior precisely because they hold social expectations about what others think or do. They may, for example, offer or solicit bribes because they believe such behavior is tolerated or endorsed by a majority of other citizens, public servants, or elected politicians (Hoffmann and Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2021). Or, more generally, they may behave corruptly because they believe that other similarly situated individuals would do so. In such instances, people would initiate bribery transactions because they assume that form of corruption is widespread and there is a low risk of punishment because they think most people tolerate such behavior. Thus, the prevalence of the corrupt practice would have less to do with whether it is generally unacceptable or illegal and more with whether they think others engage in the practice (Hoffmann and Patel, Reference Hoffmann and Patel2021)

In our view, diagnosing the social beliefs that drive (and not just enable) harmful practices such as corruption is an essential starting point for developing policy responses to change such practices. If a practice is driven by social expectations, attempting to motivate behavioral change at an individual level will be ineffective at inducing community-wide behavioral change. Curbing corruption in a situation where it manifests as a collective practice underpinned by social expectations often requires policy interventions aimed at changing the shared beliefs and expectations of entire communities rather than targeting the personal beliefs of individuals (Tankard and Paluck Reference Tankard and Paluck2016).

This article contributes to and advances ongoing shifts in corruption studies by presenting a granular view of some community expectations which contribute to a tolerant environment for certain bribery practices in Nigeria namely: (a) bribery to avoid the official process of traffic violation, (b) bribery to access a hospital bed in a government-funded health facility, and (c) bribery to obtain a pass mark in a national exam.

To do this, the research presents a rudimentary typology of petty bribery (Figure 1) based on the modalities of social expectations which incentivize and sustain the different observed behavioral patterns. This typology highlights the distinction between (a) acts of bribery that individuals carry out independently of others and are typically “one-off” transactions to overcome problems, (b) acts of bribery that individuals engage in out of certain empirical or descriptive expectations even when they hold personal beliefs that condemn bribery, and, finally, (c) acts of bribery which serve as an investment to create a relationship of future usefulness. The third variation is driven by norms of reciprocity (Sardan, Reference Sardan1999) and more often than not associated with judgments about the functionality and mutuality of bribery transactions but exists as a mechanism that makes corruption behaviors resilient and difficult to change. While these modalities of bribery behavior can exist distinctly, they may also intersect, or one form can lead to another depending on the situation. Irrespective of their situational relationship, an understanding of this basic typology is worthwhile because each modality has different implications for anti-corruption programming.

Figure 1. Typology of petty bribery.

To diagnose types of social expectations and support a behavioral modalities-driven typology of petty bribery, this research adopts social norms methodology which allows us to systematically explicate the underlying cause(s) of a behavior, even if the behavior is not driven by social expectations (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2006). In this article, we provide evidence of our social expectations measurements and enrich the literature on shared beliefs of petty bribery in three interrelated areas.

First, we highlight how often mistaken social beliefs—which result in a general phenomenon called pluralistic ignorance—are present when bribery behavior is commonplace. We show how individuals, in the contexts where bribery exchanges often occur, can be mistaken about the distribution of personal normative beliefs within their communities (i.e., they hold erroneous normative expectations). This suggests that we cannot always rely on the assumption that there is conformity between the objective consensus (i.e., the personal normative beliefs of members of the community) and perceived consensus (the normative expectations—what members of the community believe others believe—regarding the members of their community). In situations like this, the gap between private beliefs and public conduct means that individuals may falsely infer that others in their community implicitly endorse a practice because they observe them participating in it, even if most community members hold negative personal normative beliefs toward it. Differences between an individuals’ normative expectationsFootnote 1 and personal normative beliefs in their community (the objective consensus) of their community are especially prevalent with behaviors that are widespread but are not openly discussion (for fear of violating a moral taboo, for example) (Katz, Reference Katz1981, p. 28). Significantly, this article—as far as we know—is the result of the first study on corruption in Nigeria to draw attention to the gap between people’s personal normative beliefs—how community’s actually view petty bribery—and people’s beliefs about the beliefs of others in their community.

Second, this study presents qualitative evidence that people’s evaluations of bribery solicitation are setting-dependent, which means that it is viewed negatively in some settings and less so in others. This is depicted by the differences between bribery in traffic law enforcement and healthcare access situations. Finally, our analysis reveals the collective action impediment of pluralistic ignorance and argues that coordinating on anti-corruption will be challenging if most people assume other people in their community endorse corrupt behavior. These findings help explain the collective action challenge of anti-corruption in many similar contexts where corruption is entrenched and reproduced through shared beliefs, but also highlight an opportunity for designing anticorruption messages in a way that exposes the gap between perceived and objective consensus and shows communities that they have more, not fewer, likeminded individuals in their community with which they can cooperate to enact change. Results from lab experiments which show that individuals are motivated to pursue collective action when they are informed of the preference of others to also pursue collection action, highlight the central role of information in anti-corruption (Yap, Reference Yap2017).

2. Corruption and Pluralistic Ignorance

Pluralistic ignorance is a cognitive state and social phenomenon identified in psychology literature in the 1920s (Allport, Reference Allport1924). It speaks to situations where “people operate within a false social world” (Fields and Schuman, Reference Fields and Schuman1976, p. 427) forming “patterns of false beliefs” (O’Gorman, Reference O’Gorman1986, p. 335) that are either “individually inferred or collectively shared” (Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Harvey and Beu2000, p. 353). It is typically driven by the false belief that an individual’s own private judgments and feelings are different from those held by similarly situated others (Allport, Reference Allport1924; Miller and McFarland, Reference Miller, McFarland, Suls and Wills1991) even when their public behavior is identical (Bicchieri and Fukui, Reference Bicchieri, Fukui, Galavotti and Pagnini1999, p. 131; Jackson and Köbis, Reference Jackson and Köbis2018, p. 4).

Pluralistic ignorance contributes to situations where individuals misjudge the motives of others and consequently misjudge their beliefs. Individuals wrongly conclude that everyone else’s behavior reflects, and is automatically consistent with, their respective beliefs. Individual judgments in such situations are not necessarily ignorant. They are instead best described as systematically mistaken because they are merely informed by what individuals observe others doing. Such empirical evidence is compelling and can cause individuals to wrongly infer that the actions of others mirror how they are thinking and feeling (Bicchieri and Fukui, Reference Bicchieri, Fukui, Galavotti and Pagnini1999, p. 131; Jackson and Köbis, Reference Jackson and Köbis2018, p. 4) Consequently, a majority of a group may privately reject a norm or practice but nonetheless conform to it because they falsely assume that others agree with it or find it acceptable because they observe them engaging in the practice.

An important feature of contexts where pluralistic ignorance occurs, according to Bicchieri and Fukui (Reference Bicchieri, Fukui, Galavotti and Pagnini1999, p. 132), is the absence of clear communication—if at all—among individuals. This is typically the case when people’s public behavior does not match their personal beliefs as is often the case with activities proscribed by religious teachings, for example. Members of a religious community may assume uniform compliance to religious rules but cannot verify this by questioning others for fear that initiating a discussion might be interpreted as evidence of personal deviance and thus expose them to the risk of ostracization from their community (Bicchieri and Fukui, Reference Bicchieri, Fukui, Galavotti and Pagnini1999).

Corrupt practices—hidden behaviors and taboo subjects as they often are—lend themselves to precisely the kind of false inference explored in this article which can contribute to perverse circumstances in which the majority of individuals privately reject a behavior but nonetheless falsely believe that the majority of others approve of it and fear the consequences of personal deviance. Petty bribery can become self-perpetuating and impede collective action in an environment where people are systematically mistaken about the beliefs of others in their community and truthful and transparent communication is lacking (Baez-Camargo et al Reference Baez-Camargo, Bukuluki, Lugolobi, Stahl and Kassa2017).

In this article, we adopt an expanded definition of pluralistic ignorance that calls attention to the gap between what people think (perceived consensus) and what they think others in their community think (objective consensus)—identified as the “perceived self-other distance” (Eisner et al., Reference Eisner, Spini and Sommet2020, p. 26). This gap between perceived and objective consensus can play a critical role in sustaining pernicious behaviors and unpopular norms such as those that support undesirable yet common bribery practices. Inducing behavior change in contexts where forms of pluralistic ignorance are as prevalent as the behavior itself, often involves exposing the false beliefs that a norm exists in support of the behavior (see Miller and McFarland, Reference Miller, McFarland, Suls and Wills1991; Miller and Prentice, Reference Prentice and Miller1993; Prentice and Nelson, Reference Prentice and Miller2002). Corruption can be enabled and sustained by pluralistic ignorance when individuals engage in a practice that they personally think is wrong but incorrectly assume that most others in society believe it to be morally permissible or even positive. It is therefore necessary to understand how beliefs and expectations about specific corrupt practices (such as bribery) become established and the conditions under which they break down (Bicchieri and Mercier, Reference Bicchieri and Mercier2014).

Our findings on the presence of mistaken beliefs surrounding bribery behavior are illustrative of the benefits of expectation measurement in terms of nuanced evidence and the enhancement of anti-corruption programming. This approach also complements the stylized vignette approach adopted by Yuen Yuen Ang in her Unbundled Corruption Index (Ang, Reference Ang2020) which typologizes four distinct types of corruption (i.e., petty theft, grand theft, speed money, and access money). However, a key difference in our respective methodologies is that where Ang uses her vignette approach to measure perceptions, we use ours to measure expectations. We argue that while perceptions of corruption are important and more typically measured, expectations are equally important and enrich our qualitative understanding of how and why people engage in corruption.

With respect to bribery behavior, pluralistic ignorance has received some attention in corruption. Biased judgments of self versus others are shown to be an important psychological bias explored in the work of Funcke et al. (Reference Funcke, Eriksson and Strimling2014)) (referred to as the better-than-average effect), where they show through a series of online surveys, that bias occurs either in the underestimation of average behavior or overestimation of own behavior. While Lan and Hong’s (Reference Lan and Hong2017) paper is also interested in the bias mechanism underlying bribery, they are more interested in understanding the influence of social norms and gender on bribe-giving behavior and explore this through an incentivized game simulating a bribery situation. They highlight the implicit rule-basis versus illegality view of bribe-giving in many societies, with the examples of patients giving “red pockets” to doctors in China—not an uncommon practice in Nigeria, as well as tipping officials in driver’s license examinations in India (Bicchieri and Fukui, Reference Bicchieri, Fukui, Galavotti and Pagnini1999).

These studies correspond with our evidence in terms of highlighting that where bribe-giving is prevalent, pluralistic ignorance is also present. It is often the case that people may disapprove of a bribery norm individually or privately but erroneously believe that other people approve of bribery because they have observed it happen routinely in their society. Based on the empirical knowledge of most people in such a society, bribery can become entrenched and harmful beyond the actual acts of bribery themselves. It can become a proxy for showing reciprocity, loyalty, solidarity, and cooperation and this can severely weaken a society’s capacity for collective action against corruption.

Social norms and petty corruption are also explored in the work of Köbis et al. (Reference Köbis, Troost, Brandt and Soraperra2019)), where they conduct a lab-in-the-field study of descriptive norm messages and their result confirm the notion of a “corruption trap” in places where people perceive bribery as commonplace. Their work also presents some of the first field evidence which shows most people consider bribery—both personally and socially—inappropriate. Thus, supporting the school of thought that when descriptive and injunction norms are out of sync, descriptive norms often gain the upper hand (Köbis et al., Reference Köbis, Troost, Brandt and Soraperra2019). This evidence corresponds with a growing body of work, including ours, on the importance of distinguishing between descriptive and injunctive norms to gain a more rounded understanding of the social and behavioral mechanisms of corruption in different societies and settings.

3. Methodology

This research uses data from two rounds of the Chatham House Africa Programme’s Local Understandings, Expectations, and Experiences survey which involved 4,200 households in the first round and 5,600 householdsFootnote 2 in the second across urban and rural areas in six of Nigeria’s 36 federal states, namely: Adamawa, Benue, Enugu, Lagos, Rivers, Sokoto, and the capital city of Abuja. ImplementationFootnote 3 was carried out through a test-run phase and pilot before the full roll-out from October to November 2016 and November to December 2018, respectively.

The survey implementation partner, Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), updated its National Integrated Survey of Households (NISH) frame covering all 36 federal states in Nigeria and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Abuja, with 200 Enumeration Areas (EAs)Footnote 4 per state and in FCT-Abuja. This NISH master sample frame was constructed out of the original master frame of the National Population Commission (NPC) for the Housing and Population Census of 2006, which established 23,280 EAs (30 EAs for each of Nigeria’s 768 local government areas [LGAs] and 40 EAs for each of FCT-Abuja’s six Area Councils). The 200 EAs that make up the NISH frame are grouped into 20 independent replicates with 10 EAs in each replicate. The Chatham House Africa Programme’s Local Understandings, Expectations, and Experiences survey of both 2016 and 2018 drew samples from the NISH frame of 200 EAs.

The demographic, sociocultural, economic, and political dynamics such as urbanization, poverty and conflict found in the surveyed states offer some insights into shared beliefs and expectations of petty bribery in Nigeria, as well as uncovering some local specificities and factors.

3.1. Survey instrument

The survey data discussed in this article covers selected aspects of a larger instrument using social norms methodology that contained a series of survey questionsFootnote 5 regarding understandings, beliefs, experiences, and expectations about various situation-specific types of corruption. The subnational locations of 6 of Nigeria’s 36 federal states and the capital city, namely: Adamawa, Benue, Enugu, Lagos, Rivers, Sokoto, and Abuja, were selected to enable regional comparisons and an understanding of the relationship of beliefs about corruption and other contextual factors such as poverty, conflict, religion, and gender.Footnote 6 Lagos state, which includes Nigeria’s largest city, and Abuja are the most ethnically and religiously diverse locations covered in the survey, and they have the highest concentrations of both public and private schools. Lagos is also Nigeria’s and West Africa’s major commercial center while Abuja is Nigeria’s seat of government and the center of political power and government-resourced patronage networks. Sokoto, Adamawa, and Enugu states are Nigeria’s first-, fourth- and tenth-ranking poorest states, respectively (NBS, 2022), while Benue state is notable for its high agricultural productivity. Finally, although Rivers is one of Nigeria’s richest oil-producing states, its population suffers low development outcomes in the politically contested Niger Delta region. To complement and contextualize the survey data, qualitative interviews were conducted in each state including the capital territory.Footnote 7

The household surveys in 2016 had four parts while the 2018 survey had five parts. The findings from two parts of the 2016 survey and one part of the 2018 survey are discussed, others are omitted as they are outside the scope of this article. Before we present our empirical evidence of these bribery-related beliefs and expectations in the surveyed states, we will first use supplementary data to establish the prevalence, frequency of bribery, and then introduce our survey findings which establish the knowledge of illegality of the bribery behaviors in question (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Map of Nigeria showing states where survey was implemented. Source: Chatham House Africa Programme.

3.2. Prevalence and frequency of bribery in Nigeria

Overall, corruption is considered a widespread phenomenon in Nigeria and the country has maintained very low ranking in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index for its control of corruption (see Transparency International, 2021). According to Afrobarometer, Nigeria was one of four African countries (alongside Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ghana) where citizens were the most negative about the scale of corruption in their country (Afrobarometer Publications from Six Survey Rounds (1999–2015). People in Nigeria (along with Ghana and South Africa) were most likely to say that they thought corruption had risen in the 12 months prior to when the study was conducted (between June 2015 and May 2016) and three-quarters or more respondentsFootnote 8 said corruption had increased somewhat or a lot (Afrobarometer Publications from Six Survey Rounds, 1999–2015).

With respect to bribery (i.e., solicitation and giving), supplemental data also shows that this is a common and observable practice during routine interactions between citizens and public officials. In the abovementioned Afrobarometer study, 43% of public service users in Nigeria said they had paid a bribe in the prior 12 months.Footnote 9 In two other surveysFootnote 10 conducted in 2016 and 2019 by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) on the prevalence and frequency bribery in Nigeria, of all the respondents who had at least one contact with a public official in the 12 months prior, 32. 3% and 30.2%, respectively, said they paid a bribe or were asked to pay a bribe by a public official (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2016, 2019). A majority of those who paid a bribe also did so more than once. Bribe-payers in Nigeria paid an average of six bribes in 1 year, or roughly one bribe every 2 months (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2016, 2019). In our surveyed states, bribery remained relatively prevalent and frequent across the 4 years between the surveys (Figure 3). Only in the case of Enugu and Sokoto, was bribery reported as more and less prevalent respectively.

Figure 3. Prevalence of bribery.

On the side of bribe solicitation during contact with public officials, in situations where citizens were asked to pay a bribe, the UNODC study showed that officials working in road traffic management, healthcare, and education, directly requested bribes over 50% of the time (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2016, 2019; Figure 4).Footnote 11 While on the side of bribe-giving, our qualitative research confirms that this practice is not always the result of a bribery demand or extortion in all situations.Footnote 12 For example, bribe-giving was likely to occur due to teachers threatening pupils with poor grades if they are not “settled” or a parent offering a bribe to guarantee a pass mark. There are further distinctions that may occur in these contexts: bribes may serve as a remedy for poor teaching or preparation for an examination; or as the easy solution for a pupil from a wealthy family who has not prepared for the examination; or even as a form of security for concerned parents who believe others pay bribes and believe the bribes of others are likely to skew the outcomes of the examinations and put their children at risk of being failed. Therefore, bribery can occur as a settlement, solution, or security. These distinctions have not been systematically explored in the present study, but certainly warrant further investigation given how this might enhance approaches to address bribery in school settings.

Figure 4. Percentage distribution of directly requested bribes (public official type).

4. Findings

We tested bribery behavior in three critical settings: traffic law enforcement and public-funded hospitals in 2016, and explored the schooling context, specifically petty bribery in schools for improved grades, in 2018.Footnote 13 During survey implementation, enumerators were instructed to explicitly avoid using words such as “corruption,” “bribe,” or “bribery” and none of these direct references to illegal practices were included in the survey instrument. Instead, survey questions and vignettes referred to “direct payment” or “giving money,” and similar less judgemental phrasing.Footnote 14 Survey implementers made it clear to respondents that the questions and vignettes concerned routine encounters they or members of their household might have with public officials and then they were presented with scenarios involving a traffic law violation, need for hospital admission, and a child sitting for a national examination. Once the scenario was established, the respondent was asked about their beliefs about informal/direct payments or giving money in this context to either avoid official traffic law violation penalties, speed up hospital admission or secure a passing grade in a national examination. By avoiding the explicit or blunt terms of “bribes” or “bribing” and masking some questions in a vignette form, the survey reduced the impact of social desirability (i.e., the tendency for respondents to provide answers they think are “correct” or socially, morally, or legally acceptable instead of response that reflect their true beliefs).Footnote 15

In all three contexts, knowledge of legality was established at a high level for all instances especially as it relates to informal payments to avoid traffic law violation. A minimum of 60% and maximum of 97% of respondents thought the practice being described was illegal (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Legal knowledge (“Yes” respondents).

4.1. Traffic law enforcement

Road users in Nigeria are routinely subjected to vehicle inspections by a host of government agencies that are responsible for enforcing traffic laws and regulations as well as civic protection and crime prevention. These agencies have a visible presence on roads in both urban and rural areas across Nigeria. Typical agencies involved in traffic law enforcement include the Nigeria Police Force, Federal Road Safety Commission, Vehicle Inspection Office, and Driver and Vehicle Licensing Administration. Although many officers from these agencies conduct themselves in a professional manner, the daily interactions between citizens and armed police officers, road safety officers, or vehicle inspection officers tend to be a rich context for bribery demands and extortionate behavior. Road users accused of traffic law violations are often the prime targets of bribe solicitation, and survey responses shed light citizen’s real-world beliefs, choices, and preferences.

Our qualitative data showed that law enforcement agents who ask for bribes from road users for traffic violations have incentives to increase the overall cost of going through the official process by using their discretion to draw out those processes. To reinforce the bribe demand, the amount of money that is asked for by a law enforcement agent to avoid a fine is typically lower than the actual amount of the supposed traffic violation.Footnote 16 Where a person refuses to pay the officer who has solicited the bribe, the penalty becomes hefty in terms of the time required for filing paperwork and going to the bank in order to pay the fine. To avoid the complex official process, people engage in giving bribes even when they know this action is illegal and wrong.

When asked whether they thought it was wrong for law enforcement officers to ask for a direct payment to avoid the official process for a traffic violation, almost as many respondents who thought this behavior was illegal also thought it was wrong (Figure 6). In Enugu and Sokoto, 96.7% and 95.8% of respondents, respectively, thought it was wrong—roughly 3% and 2% higher than those who thought it was illegal. The relatively lowest percentage of respondents who thought it was wrong (held negative personal normative beliefs about the practice) was recorded in Abuja, at 78.3% (see Supplementary Material for full results).

Figure 6. Personal normative beliefs (“Yes” respondents to traffic law violation bribery).

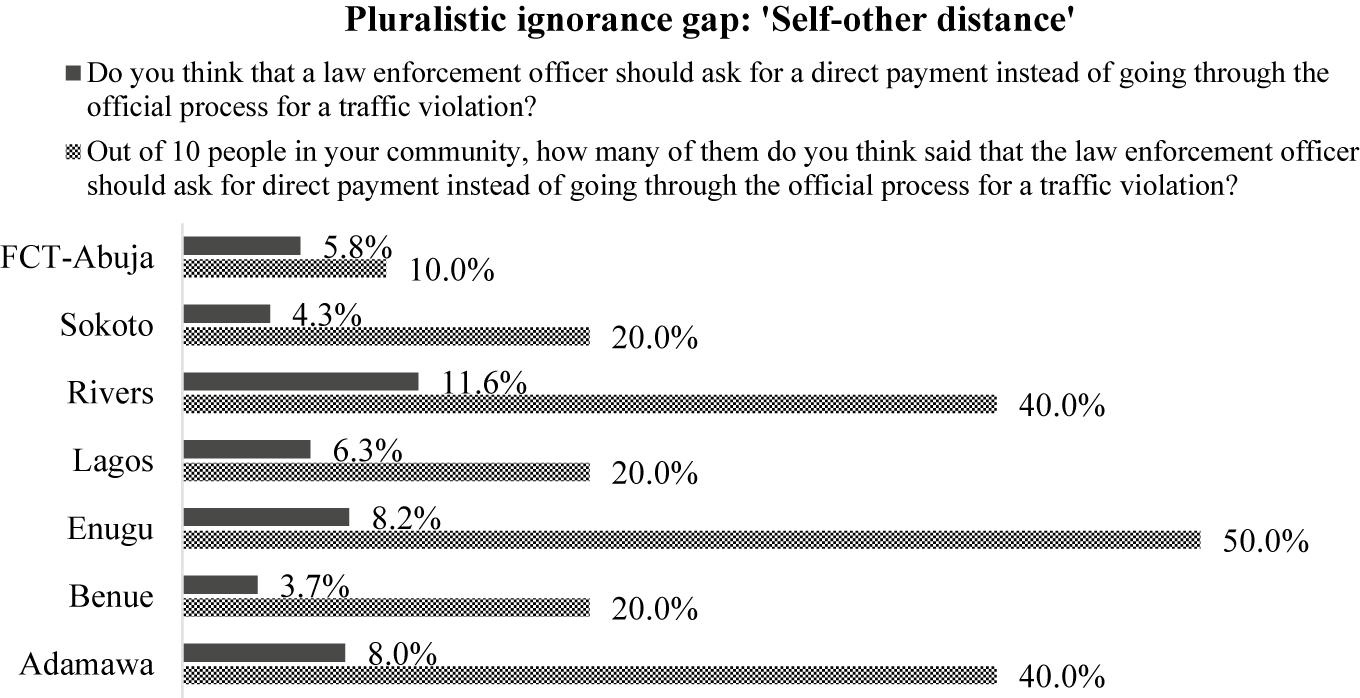

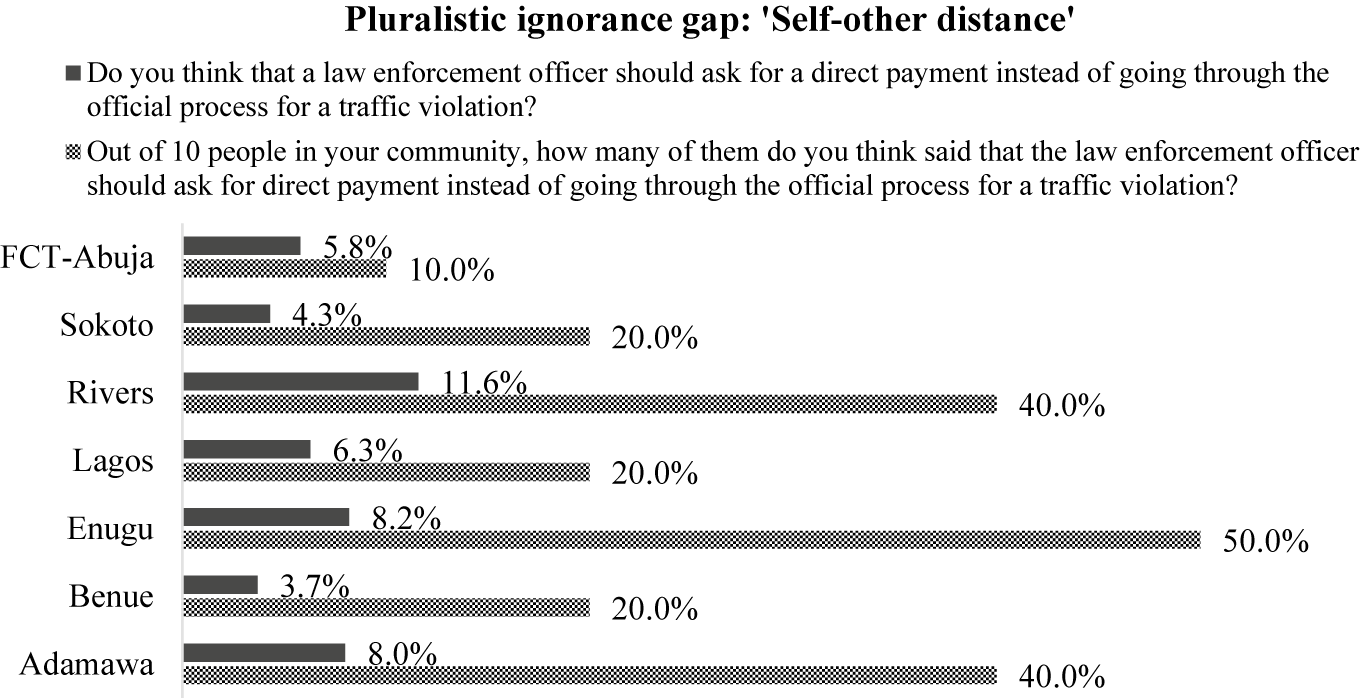

In order to introduce variance and further isolate personal normative beliefs, respondents were further asked if they thought law enforcement officers should ask for a direct payment instead of going through the legal process for a traffic violation. The personal approval of the solicitation of traffic violation bribes was also very low—under 10% in most states—and lowest in Benue at 3.7%.

Once the survey had established knowledge of legality and personal normative beliefs, respondents were asked about their empirical expectations (i.e., expectations people hold about how others behave or the experiences of others) about the practice of direct payments to avoid official traffic violation procedures. In three states (Adamawa, Benue, and Rivers), respondents thought that 5 out of 10 people in their community were asked to pay money directly (Figure 9). In the case of Enugu, respondents thought that 8 out of 10 people in their community were asked to pay money directly to a law enforcement officer rather than go through the official process.

Following the establishment of empirical expectations, respondents were asked about their second-order beliefs (i.e., their beliefs about other people’s beliefs, which also refers to their normative expectations) (Figure 7). In Adamawa, and Rivers, respondents believed that 40% of their community would say a law enforcement agent should ask for a direct payment instead of going through the official process for a traffic violation even though their personal normative beliefs were higher (87.8% and 82.5%, respectively). In Enugu state, while 9 out of 10 people (about 90% of respondents) considered that it is wrong and illegal for law enforcement agents to ask for a bribe, they thought that just 5 out of 10 of their fellow citizens share the same high negative personal normative belief against traffic law agents asking for direct payments to avoid the official traffic violation process (Figure 8).Footnote 17

Figure 7. Normative expectations (traffic violation law bribery).

Figure 8. Empirical expectations across all situations (“Yes” respondents to traffic law, hospital bed access and pass mark contexts).

Using our expanded definition of pluralistic ignorance that focuses on the gap between perceived and objective consensus, we find a significant “perceived self-other distance” between respondent’s negative personal normative beliefs and the beliefs they perceive are held by others in their community about traffic law-related bribery behavior (see Figure 9). This gap suggests that a considerable number of citizens could be systematic mistakes about what others in their community believe about bribery solicitation to avoid the official traffic law violation process and assume their own personal normative beliefs are different from those held by others.

Figure 9. Pluralistic ignorance (“Yes” respondents to traffic violation bribery).

4.2. Accessing health services in a government-funded hospital

In Nigeria’s policy on the basic standard of primary healthcare at the ward level (specifically from the level of primary health clinics), publicly funded facilities are to have a minimum number of inpatient ward beds (National Health Act No. 8 of 2014). In principle, citizens needing these beds while receiving medical treatment should not be asked to pay for admission, but the norm and practice deviate sharply from this policy. Many government-run hospitals in Nigeria are severely underfunded and poorly equipped. Nigeria also operates a mixed model of healthcare financing whereby certain services, for example, preventive interventions like immunizations, are supposedly available free of charge to the public while other services such as hospital care are subsidized. Thus, the reality is very varied, because actual availability of free and subsidized services and supplies is very poor and there are considerable variations in modes of financing and availability of public healthcare from state to state.

Years of deficits in public funding for healthcare, coupled with massive embezzlement and financial mismanagement, have led to an availability and quality crisis in the sector that has fostered a culture of routine demands for bribes by health workers and experiences of extortion in public healthcare settings (Onwujekwe et al., Reference Onwejekwe, Orjiakor, Hutchinson, McKee, Agwu, Mbachu, Ogbozor, Obi, Odii, Ichoku and Balabanova2020) in order to keep services going and regulate their distribution. It is not uncommon for priority of care to be given to those who can make an informal payment, rather than based on how critical and serious the medical emergency is.

Furthermore, in many health facilities, there are no clearly displayed lists showing the cost implications to users of services or procedures, and charges often seem arbitrary and can be negotiated down. Even where official-looking receipts are issued, users cannot be sure whether they have been extorted or if payments have been legitimately directed into the hospital’s accounting system. When we evaluate bribery behavior for accessing a bed in a publicly founded hospital, besides the self-other distance in some states which suggests pluralistic ignorance, we found that respondents had quite different beliefs about bribery in this context compared with the traffic law enforcement context.

When asked whether they thought it was wrong for a healthcare worker facility to ask for an informal payment for admission (i.e., personal normative beliefs), most people—as was the case for informal traffic violation payments—thought this practice was illegal (Figure 5) but fewer respondents thought it was wrong compared with the traffic law context (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Personal normative beliefs (“Yes” respondents to hospital bed access bribery).

Respondents also held relatively average empirical expectations of other people’s experiences of being asked to pay for a hospital bed in a government health facility (see Figure 8). In the case of Enugu and Rivers, respondents said they thought that 5 out of 10 people (50%) in their community said that they had been charged for a hospital bed against just over one in 10 in the FCT (12.3% of Abuja respondents). The empirical expectations of respondents in Abuja may reflect the fact that health facilities in the capital territory receive more funding and hospital beds are more available compared with the state level, or the likelihood of a government hospital employee being exposed and punished for demanding a bribe is greater because of the higher concentration of senior public-sector employees and government officials among healthcare users in Abuja.

It is, however, notable that respondents hold very different beliefs with respect to interactions with employees in government health facilities from those regarding traffic law enforcement officials, even though corrupt activity can occur in both situations (see Figures 6 and 10).Footnote 18 Our qualitative data also supports the probability that people think about the functions of bribery in these two contexts differently and adjust their beliefs accordingly. In the traffic law enforcement context, bribery is viewed as primarily extractive while in the healthcare setting, it is transactional or compensatory or at least more functional and perceived to be beneficial to the bribe-giver (a service user or one’s family member) and bribe-solicitor (healthcare worker trying to provide much-needed healthcare in an under-resourced environment).

Therefore, people do not seem to hold negative beliefs toward healthcare bribe-giving when you compare those beliefs with their beliefs about law enforcement bribe-giving. In the case of healthcare, bribery transactions seem to serve a market-clearing function due to the lack of resources, supplies, and low wages at public health facilities and users lack information about rates and as a result, may not even know they have been extorted. Most respondents do not then believe paying a bribe at a health facility is wrong but nonetheless think most other people believe the same to be wrong. This suggests bribery in the health context is likely viewed as efficient, helping those who can afford the bribe to get better services or jump the queue, but it leaves poorer service users lacking the resources for bribes at a disadvantage and at the back of the queue.

With regards to the discussion of the functionality of these types of transactions, this aspect is further supported by supplementary data which shows that in the case of bribe payments to medical professional, speeding up procedures is a frequent reason (60% of the time) followed by it serving as a “sign of appreciation” (12%). In terms of our typology of petty bribery (see Figure 1), transactions in this case are more often “one-off,” but 20% of the bribe payments (see Figure 11) are driven by descriptive norms or social norms of reciprocity. This is also similarly the case for the purpose of bribe payments for traffic law violations. Road users often wish to either speed up the process or avoid a fine, so they are likely to give one-off or descriptive norm-driven bribes. Bribers seem much less likely to pay bribes as a sign of appreciation (i.e., reciprocity or an understanding of cooperation or mutuality; Figure 12).

Figure 11. Purpose of bribery (public official type).

Figure 12. Normative beliefs (hospital bed access bribery) (In this case, normative beliefs were tested using just one question as opposed to two variances in the other cases).

Following the establishment of personal normative and empirical expectations, the survey found that in some states, respondents held second-order beliefs (i.e., normative expectations) that indicated they thought that other people would think it was wrong for a government healthcare worker to ask for an informal payment even though most respondents thought bribe solicitation in this context was acceptable.

Again, we found evidence of the perceived self-other distance, in that people were mistaken about what others in their community believed (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Pluralistic ignorance (hospital bed access bribery).

4.3. Pass-mark bribery in a national exam

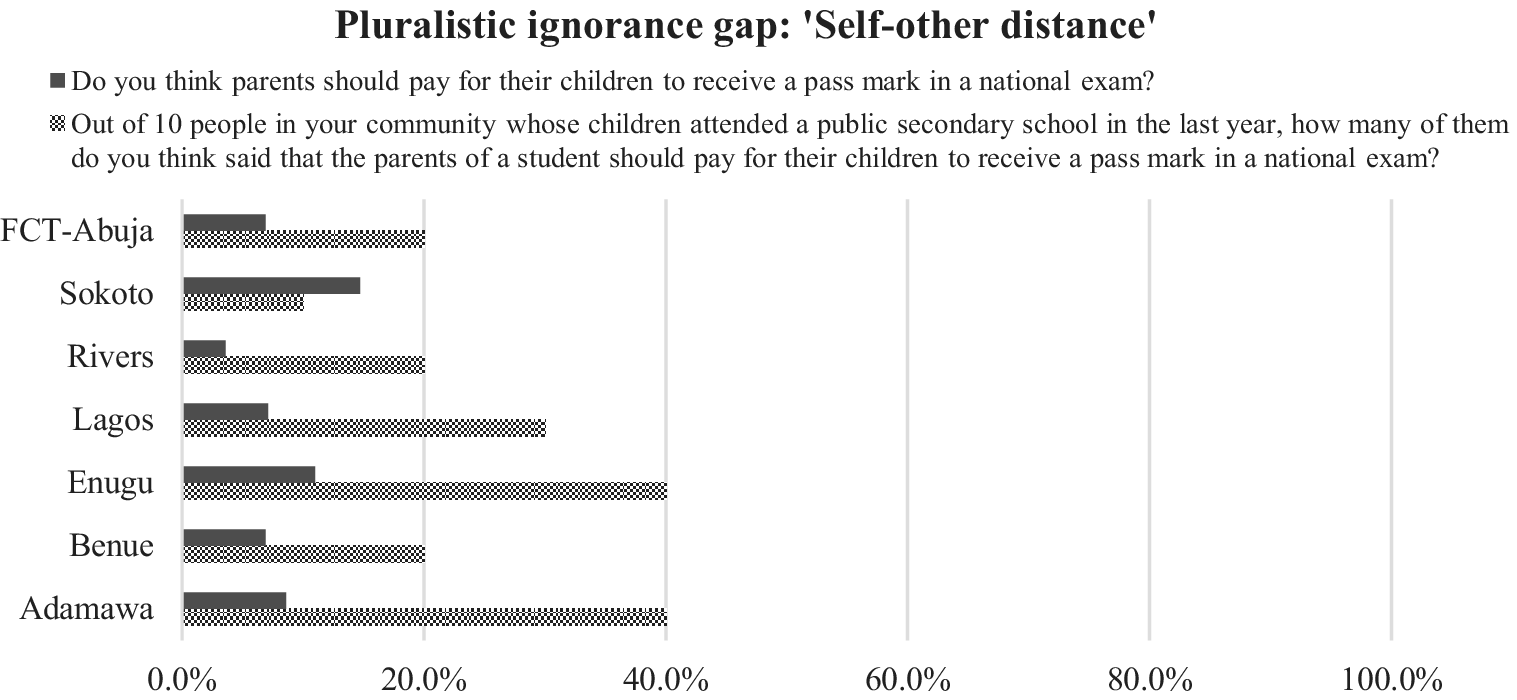

The subsequent social expectations survey of 2018 included a component which assessed beliefs surrounding petty bribery in education—specifically for a pass-mark in a national exam. When asked whether they thought it was wrong for parents to pay for their children to receive a pass mark, almost as many respondents who thought this behavior was illegal (see Figure 5) also thought it was wrong. The survey found that over 87% of respondents thought that parents should not pay pass-mark bribes, against 8% in favor (Figure 14). This means a large majority of respondents held negative personal normative beliefs about this bribery behavior and considered it unacceptable even though it might be commonplace.

Figure 14. Personal normative beliefs (“No,” “yes,” and “yes” respondents to pass-mark bribery) (The 2018 survey questionnaire replaced the use of “wrong” with “should not” over concerns of moral judgment that might be associated with the former. To vary the question while still assessing personal normative beliefs, “should not” was used).

However, when we turned to look at people’s empirical expectations (Figure 9), which often aid the entrenchment of descriptive norms of bribery, we found that respondents in places like Adamawa and Enugu, held high empirical expectations with respect to pass-mark bribery. This means they believed that on average 4 out of 10 people (40%) in their community paid for their children to receive a pass mark in a national exam.

Following the establishment of empirical expectations, respondents were asked about their second-order beliefs (i.e., their beliefs about other people’s beliefs or normative expectations). In most communities, respondents though a significant number of people in their community supported or approved of pass-mark bribery behavior, even though most respondents in those same communities personally disapproved of the practice.

Again, in places like Adamawa and Enugu, we see residents thinking that 4 out of 10 parents paid a pass mark bribe and 4 out of 10 community members approve of this practice (see Figure 15). This evaluation differs significantly from the only 8.6% and 11% of respondents, respectively who personally thought parents should pay bribes to teachers.

Respondents across all the states (Sokoto in the northwest appears to be a bit of an outlier), held low positive personal normative beliefs toward pass-mark bribery relative to their high empirical and normative expectations. The modalities driving pass-mark bribery also seem descriptive as parents hold high empirical and normative expectations.

Figure 15. Normative expectations (pass-mark bribery).

Furthermore, this important discrepancy between what people feel is the right way to behave (their personal normative beliefs) and how they believe others in their community actually think about pass-mark bribery (their second-order beliefs) suggests people in these states were pluralistically ignorant of the shared negative normative beliefs of others (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Pluralistic ignorance (pass-mark bribery).

5. Discussion

As we have noted, our expanded definition of pluralistic ignorance refers to a situation in which the private beliefs of individual group members (objective consensus) differ from what are perceived to be the public beliefs of the group supported by group behavior (perceived consensus). In these situations, there is a gap between the perceived consensus (a reflection of group members’ second-order normative expectations) and the objective consensus (a reflection of group members’ actual personal normative beliefs) driven by members’ false inference that others do not believe what they believe even though personal beliefs and public behavior are almost identical.

Consider pass-mark bribery. In all states but Sokoto, respondents systematically overestimated the actual incidence of positive normative beliefs within the relevant communities. In other words, respondents thought that there was a higher percentage of group members who held positive normative beliefs toward pass-mark bribery than was actually the case (see Figure 15). We found this discrepancy to be highest in states that had the highest empirical expectations (i.e., where pass-mark bribery was perceived to be the most widespread; Figure 8). For example, respondents in Adamawa and Enugu thought that 40% of their community held positive personal normative beliefs toward pass-mark bribery when in fact only 8.6% and 11% held those beliefs.

Pluralistic ignorance seems to be a common feature under conditions of bribery. After all, corruption is ubiquitous in these contexts, from petty bribery exemplified through practically unavoidable impersonal markets to the conspicuous grand corruption on display from wealthy politicians and their ostentatious lifestyles. This is made even more challenging when people have strong economic or livelihood imperatives for bribe-giving when it is the most reliable option for reducing costs associated with cumbersome official processes, accessing desperately needed public services or augmenting dysfunctional and underfunded institutions. The integration of corruption into the everyday life of the society provides ample opportunity for individuals to falsely infer that those around them believe that corruption is inevitable, acceptable, or even desirable.

This is true even with respect to practices that are universally condemned. Consider pluralistic ignorance surrounding traffic law enforcement practices. In every state, an overwhelming majority of respondents thought that it was wrong for a traffic law enforcement officer to ask for a bribe for a traffic violation and only a relatively small minority of respondents held positive personal normative beliefs toward police bribery (Figure 6). Respondents, however, thought that many more individuals in their communities were in favor of bribery solicitation to avoid official traffic law processes than was actually the case. For example, respondents in Adamawa and Enugu thought that 40% and 50% of their community (respectively) held positive personal normative beliefs toward bribery solicitation when in fact only 8% and 8.2% held those beliefs (see Supplementary Material). This discrepancy between perceived and objective consensus was observed in every state to varying degrees.

We argue that the observed gap between perceived and objective consensus may be an obstacle to anti-corruption efforts where corrupt practices are thought of as prevalent. When individuals believe that those around them find corruption acceptable or desirable, they may perceive the costs of collective action to be higher and may even come to view corruption as an inevitable feature of their societies. Indeed, they may come to believe that there are not enough people within their community with whom they might effect change through an alignment of positive personal beliefs. Believing that half of the individuals in a community believe that one should engage in pass-mark bribery or government-paid medical professionals should solicit bribes in healthcare facilities is expectedly discouraging and may elicit a fatalistic attitude toward the prevalence of corruption and the inevitable infeasibility of anti-corruption policy.

Moreover, individuals tend to shift their private beliefs toward their perception of the perceived consensus. This means they will not only conform to the prevailing group’s behavior, but they will align their beliefs (as they perceive them). This is a means of resolving the conflict between one’s beliefs and the group’s beliefs in order to avoid the costs of revealing true beliefs. Expressing one’s true beliefs in this situation might mean isolation; attempting to change the group’s beliefs is also risky or might seem infeasible (Bjerring et al., Reference Bjerring, Hansen and Pedersen2014). Both options are risky in the sense that they require one to challenge the prevailing group norm (as they perceive it). This means that, in some cases, the perceived consensus becomes the objective consensus, even if the actual behavior of the group was widely unpopular. In demonstrating this gap, we confirm the original findings of Funcke et al. (Reference Funcke, Eriksson and Strimling2014) that people tend to consider themselves to be less prone to corrupt behavior than the average person and support the argument that such systematic mistaken beliefs undermine efforts to shift norms in the direction of less corruption.

A culture of widespread petty bribery and extortion may seem innocuous, or even beneficial, in some circumstances, since it may at face value be cheaper for an individual to pay a modest bribe rather than incur the greater costs involved in paying a prescribed penalty fine or going through official processes (Elliott, Reference Elliott1997). One interviewee in Sokoto, for instance, noted that: “People only see grand corruption as the “real” corruption.Footnote 19 Petty corruption is not really corruption.” However, the cumulative effect of petty corruption is harmful. First, widespread petty bribery disproportionately targets the poor, and helps keep them poor (Johnston, Reference Johnston2004). Second, it diverts resources away from legitimate and beneficial activities to illegitimate and unproductive ones (see Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman2002). Third, it tends to be linked to, or indicative of, more substantial forms of corruption, as senior officials or employees allow petty corruption by junior ones to continue so that collusion in systemic corruption is assured (Rose-Ackerman and Palifka, Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). Fourth, and perhaps most important, the aggregate effects of widespread petty corruption serve to undermine the legitimacy of government institutions in general, and their capacity to fairly administer public goods and services as well as protection under the law (Elliott, Reference Elliott1997, p. 175, 177, 193). The fact that more people are likely to be more directly affected by petty corruption in their day-to-day activities—for example, time spent detained at a road safety corps office—than by grand corruption exacerbates these four negative effects.

There are a number of limitations that must be considered in light of the findings we have reported. This study set out to measure social expectations of corruption to understand whether and how the pervasive phenomenon of corruption in Nigeria was sustained by social norms (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2010). The exposure of mistaken beliefs is ancillary evidence in this process. While the findings are supportive of a relationship between prevalent petty bribery and pluralistic ignorance, more research is needed to rigorously establish the accuracy and generalizability of the perceived self-other distance and eliminate other explanations. The extent to which the mistaken beliefs is causally associated with corrupt practice is an empirical question that has not been investigation in this study.

Additionally, it is plausible that the perceived self-other distance identified by the survey can be explained as some form of rational expectations in agents, but this assumption cannot consistently explain the gap across three different forms of bribery behavior which are driven by sometimes sharply different motivations (like the case of traffic violation and hospital bed access bribery). It is also possible that respondents to the survey have the tendency—as most people—not to self-incriminate and therefore not be truthful when they answer the survey about their own behavior or there was self-selection of more honest people who have a higher propensity to finish a survey on corruption. However, the survey was designed and introduced to respondents as a survey on “everyday experiences as citizens” and titled, “Local Understandings, Expectations and Experiences” survey to neutralize any association with corruption. Survey implementers were also trained not to use any references to “bribery” or “corruption” but to explain to respondents that the survey was part of “study of common experiences faced by Nigerians.” The questions were also structured to be self-explanatory and test for single rather than multiple variables to minimize the possibility of multiuse and ambiguous words.

Furthermore, the survey was implemented using a household selection procedure to avoid self-selection. Using the NBS’s NISH frame, households were selected by random and every household in the area had an equal chance of being included in the study. After the survey was introduced to the household, all eligible household members were listed (only those over 18). Following this, the respondent in the householdFootnote 20 was then randomly selected by the CAPI programming system.

6. Conclusion

There are some obvious conclusions with respect to how to coordinate on anti-corruption. The first one being that collective action is limited when people mistakenly think that other people find a behavior acceptable. Even if it is in the best interest of most people to act collectively and in keeping with their personal normative beliefs, there is little perceived incentive to do so because of the gap between perceived and actual consensus. This gap and the mistaken beliefs that can sustain privately disapproved behavior can exacerbate collective action problems, for example, by further skewing trust dynamics—generalized trust or trust in people generally (Rothstein Reference Rothstein2000). It is not just the free-rider’s self-interest as presented in collective action theory, it is also the case that the members of the community are misinformed about the normative expectations of others—others who are likeminded and likely allies in coordinating and monitoring the behavior of others in the community as well as creating norms in keeping with shared personal beliefs.

Exposing the illusion of pluralistic ignorance—that is, bridging the gap between perceived and objective consensus—may be a critical step toward initiating successful collective efforts against corruption. In some cases, a public campaign may elicit a “wave of publicity” that may “sweep through the community” that exposes the gap and informs people that others in their community also believe and think as they do (Katz, Reference Katz1981, p. 28). In other cases, focused and open deliberation that allows for open conversation may expose community beliefs and the broad agreement amongst them ((Bicchieri and Mercier, Reference Bicchieri and Mercier2014, p. 63; Bicchieri, Reference Bicchieri2016, p. 155).

The efficacy of deliberation turns on the ability of community members to speak openly and honestly about the relevant subject (even in cases where there is a norm against speaking about such subjects). Caution must be taken, however, as deliberation may run the risk entrenching the prevailing norms (e.g., in cases where participants do not feel free to discuss a particular issue for fear of violating a moral taboo). In these cases, deliberation may in fact be counterproductive as individuals may instead choose to express their commitment to a practice rather than reveal their true beliefs about that practice. This point is particularly salient in cases where power dynamics within the community are such that less powerful or marginalized participants do not feel free to challenge more powerful individuals from a dominant subset of the community. Revealing one’s true beliefs in cases like this (or in any case in which the perceived consensus diverges from the objective consensus) may be challenging as it would require—from the perspective of any given participant—expressing open disagreement with others in the community (or even most of the community). It would require, for example, participants in Adamawa and Enugu to openly question the beliefs of almost half of their community with respect to pass-mark bribery or law enforcement bribery. Discussion of these practices may also be difficult as they raise moral, political, and legal questions which may dissuade participants from expressing disagreement. Discussion that is facilitated and guided by influential members of the community—such as respected leaders—may help overcome these challenges by creating conditions in which all may participate and feel comfortable when revealing their true beliefs (Bicchieri, Reference Bicchieri2016, p. 156). While deliberation alone does not address economic incentives and structural issues that entrench corrupt practices, such as underfunded government institutions and poor service delivery, it can serve as an important step for overcoming collection action problems by reassuring members of communities of the presence of likeminded individuals if certain members wish to initiate social change.

Finally, by exploring social expectations of corruption, this research has shown that behavioral measures using surveys with vignettes can serves as important tools for uncovering sticking points for collective action against anti-corruption and thereby contribute to more evidence-based, context-specific anticorruption interventions. This is especially the case if, for example, informational campaigns with social nudge messaging are piloted to dispel pluralistic ignorance in a specific context or surrounding a corrupt behavior such as bribery. Tracking changes in people’s beliefs through longitudinal studies is also possible—for instance in understanding what mechanisms or what combination of interventions lead to people updating their beliefs.Footnote 21 As well as which messaging is most effective and which channels are most effective.

The present study shows that people are systematically mistaken about the beliefs of others in their community on certain corrupt practice. The fact that the research examines empirical and normative expectations directly and not pluralistic ignorance limits the generalizability of the findings. Additional studies could isolate pluralistic ignorance more directly and investigate its role in collective action problems. For instance, models of second-order conformity to the perceived consensus show the inefficiency of pluralistic ignorance and how it may lead to a perverse failure of collective action (Duque, Reference Duque2017). Such models—in either a laboratory or lab-in-the-field experiment—can be used to better capture concepts such as context-dependent preferences, the impact of group size on the probability of pluralistic ignorance and how different principles and policies can affect social change.

Overall, this research supports innovative approaches to understanding entrenched yet disapproved corrupt practices that is based on theory and research concerning pluralistic ignorance in especially African contexts, where these types of methods are less applied. While future research is needed to further establish the role of pluralistic ignorance—particularly within other forms of corruption such as procurement fraud—this original evidence suggests corruption studies and collective action problems would be enhanced by such efforts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/dap.2023.19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the journal’s editorial team for their constructive comments and suggestions. In collaboration with Nigeria’s NBS, the data in the article was collected by partner survey teams from universities and research centers in 6 of Nigeria’s 36 federal states and the capital territory, Abuja. A previous version of this article was presented, and generous comments received in a virtual session of the World Bank’s Data Analytics for Anticorruption in Public Administration Conference in October 2021 and a virtual seminar at the Centre for Corruption Studies Seminar at the University of Sussex in February 2022. We thank the anonymous reviewers for pointing out the need for clarity in showing graphical differences and going beyond descriptive results. We also thank the anonymous referee for suggesting we consider other possible explanations and contexualize our findings with these in view. The authors also wish to acknowledge the brilliant logistical support provided by Tighisti Amare, Daragh Neville, and Fergus Kell. We are also grateful to our partners at the national headquarters and state offices of Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics for their support in implementing the national household surveys for this research. The authors wish to acknowledge the SNAG research consortium based in Nigeria and led by the following colleagues: Dr Anthony Ajah of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Dr Kemi Ogunyemi of the Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos, Professor Elizabeth Adebayo of the Modibbo Adama University of Technology, Yola, Dr Tukur Baba and Dr Sulaiman Kura of the Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Professor Euginia Member George-Genyi of the Benue State University, Makurdi, Dr Tubodenyefa Zibima of the Stakeholder Democracy Network, Professor Daisy Onyige of the University of Port Harcourt, Rivers, and Ms. Rakiya Mohammed of the National Bureau of Statistics. We also thank Elizabeth Donnelly and Jo Maher for reviewing previous drafts of various sections of this article. The views presented in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the wider SNAG team, Chatham House, the UK’s Development, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, MacArthur Foundation, or other partner organizations.

Data availability statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this article—including survey raw data and absolute analysis data—can be found in the open-access repository Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7966520.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: L.K.H, R.N.P.; Data curation: R.N.P, L.K.H.; Formal analysis: R.N.P, L.K.H.; Investigation: L.K.H, R.N.P.; Methodology: L.K.H, R.N.P.; Writing—original draft: L.K.H, R.N.P. All authors approved the final submitted draft.

Funding statement

This publication is an output of the Chatham House Africa Programme’s Social Norms and Accountable Governance Project funded by the UK’s Development, Foreign, and Commonwealth Office from 2016 to 2017 and the MacArthur Foundation from 2018 to 2022.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.