From the discovery of the “dispute pyramid” in the 1980s (Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81) to work that calls attention to the many branches of disputing (Albiston et al. Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014), scholars have long documented rights mobilization in workplaces (e.g., Bumiller Reference Bumiller1988; Edelman Reference Edelman2016; McCann Reference McCann1994; Morrill Reference Morrill1995). Of particular importance has been the interplay between gender inequality and individual mobilization (e.g., Albiston Reference Albiston2005; Reference Albiston2010; Berrey et al. Reference Berrey, Nelson and Beth Nielsen2017; Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach Reference Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach1994; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2005; Kairys Reference Kairys1998; Marshall Reference Marshall2003; Reference Marshall2005; Wofford Reference Wofford2017). Two major limitations, however, mark this literature.

First, research on individual mobilization and gender inequality in workplaces tends to concentrate on private corporations infused with “managerialized and business values” (Edelman Reference Edelman2016: 25; cf., Marshall Reference Marshall2003; Reference Marshall2005). This focus limits what we know about mobilization and gender inequality in other kinds of workplaces, especially public organizations, (such as schools), which historically have provided opportunities for women and non-White middle-class occupational attainment. Significant in this regard are American high schools where millions of educators – teachers and administrators – work on the frontlines of long-term contestation over social inequality (Arum Reference Arum2003; Driver Reference Driver2018; Tyson Reference Tyson2011). These struggles resulted in school workplaces becoming among the most “legalized” organizations in the country, dominated by extensive law-like structures and procedures (Sugarman Reference Sugarman2021). It is unclear what individual rights mobilization and gender inequality look like in extensively legalized workplaces largely bereft of business values.

Second, the literature tells us a great deal about the choices of those whose rights have been violated in civil justice contexts, but we know almost nothing about the mobilization of those accused of violating the rights of others. The literature is therefore limited to the vantage point of complainants who often occupy lower-power positions compared to those against whom they have grievances. Moreover, gender inequality and formal status are especially salient in high school workplaces where nationally (at the time of data collection for this study), 75% of teachers identified as female, nearly 60% of administrators identified as male, and 78% of educators identified as White (Battle and Gruber Reference Battle and Gruber2010).

This article explores rights mobilization choices and gender inequality among educators as complainants and accused parties. In school workplaces, teachers are employees who can complain about rights violations they suffer while being accused of violating the rights of others. Administrators, by virtue of their power in the organizational hierarchy, may be more likely accused of violating the rights of others while suffering violations of their own rights either by coworkers or higher-ups (e.g., district administrators). To investigate these issues, we conducted a national random survey of 602 educators (402 teachers and 200 administrators) in United States high schools administered for us by Harris Interactive. We supplement this data with an in-depth interview study of 45 educators (36 teachers and 9 administrators) in California, New York, and North Carolina metropolitan areas. This research is part of the School Rights Project (SRP) – a multimethod study of law and everyday life in high schools.Footnote 1

In the following section, we conceptualize rights mobilization as a multidimensional social process in and outside formal legal channels. We then advance multiple hypotheses and research questions regarding the relationship between gender inequality, formal status, and rights mobilization, drawing from gender system theory. Next, we describe our survey and qualitative methods. Our findings interlace quantitative patterns from our survey results with qualitative interview data to shed additional light on the quantitative patterns. The paper concludes with implications for research on gender, status, and rights mobilization in light of shifting political and demographic contexts in school workplaces.

Rights mobilization as a multidimensional process

The Civil Litigation Research Project (CLRP) gave rise to much of the initial literature on rights mobilization (Trubek et al. Reference Trubek, Grossman, Felstiner, Kritzer and Sarat1983) and the concept of the dispute pyramid (Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81). The pyramid consists of a large base of grievances, only a small proportion of which evolve into claims, still fewer develop into disputes, and a tiny fraction become civil legal disputes. Miller and Sarat (Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81: 544) found that only five percent of grievances proceed to trial, a finding that subsequent studies have corroborated (Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Nelson and Lancaster2010). Miller and Sarat (Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81: 538) also showed that many people “lump” (do nothing about) their grievances with the vast amount falling out of the pyramid.

Felstiner et al. (Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980-81) theorized that rights mobilization emerges through a social process of “naming” legal problems, “blaming” a responsible party, and “claiming” a right to redress. A great deal of literature since has addressed the psychological, structural, and cultural barriers to mobilization, as well as the role of “agents of mobilization” and institutionalized ideas about appropriate behavior in influencing decisions to mobilize or, more often, not to mobilize the law (e.g., Albiston Reference Albiston2005; Reference Albiston2010; Albiston et al. Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014; Bumiller Reference Bumiller1988; Engel Reference Engel2016; Friedman Reference Friedman1990; Haltom and McCann Reference Haltom and McCann2004; Marshall Reference Marshall2005; McElhattan et al. Reference McElhattan, Beth Nielsen and Weinberg2017; Merry and Silbey Reference Merry and Silbey1984; Morrill et al. Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010; Wofford Reference Wofford2017). Other research has broadened the notion of mobilization to include resistance to authority and microlevel action in everyday social relationships (Emerson Reference Emerson2015; Engel and Munger Reference Engel and Munger2003; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey2003). Scholars also have considered the relationship between individual and collective mobilization (Albiston Reference Albiston2010; Buckel et al. Reference Buckel, Pichl and Vestena2024; Chua Reference Chua2019; Chua and Engel Reference Chua and Engel2019; McCann Reference McCann2006; Morrill and Rudes Reference Morrill and Rudes2010; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1991). Sandefur and Teufel (Reference Sandefur and Teufel2021: 763) add a novel framing to this tradition by defining “justiciable events,” some of which need legal expertise while others are best solved extralegally.

Importantly, the original dispute pyramid focused exclusively on rights mobilization within the formal legal system. The space outside the pyramid became negative space where responses to perceived rights violations are invisible. Yet, much of the literature on dispute resolution focuses on responses to rights violations that occur neither within the legal system nor via lumping it. Macaulay (Reference Macaulay1963), for example, famously discovered that the vast majority of contract disputes among businesses in Wisconsin were handled informally with disputants framing their disputes as mixtures of rights and interorganizational obligations. Similarly, Ellickson (Reference Ellickson1991) found that farmers and cattle ranchers in Shasta County, California, developed a complex social accounting process for addressing crop damage caused by roaming cattle. Numerous studies describe the rising popularity of alternative dispute resolution for handling rights claims, especially in organizations (Edelman Reference Edelman2016; Edelman and Cahill Reference Edelman, Cahill, Bryant and Sarat1998; Edelman and Suchman Reference Edelman and Suchman1999; Marshall Reference Marshall2005; Menkel-Meadow Reference Menkel-Meadow1984; Morrill and Rudes Reference Morrill and Rudes2010; Talesh Reference Talesh2012).

Albiston et al. (Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014) argue that the dispute pyramid metaphor should be replaced by a dispute “tree” with many branches of rights mobilization. Some branches represent legal forms of dispute resolution and some represent informal modes, such as alternative dispute resolution, self-help, collective action, self-reflection, or prayer. Some branches bear “fruit,” which signify the substantive benefits of rights, whereas others bear “flowers,” representing symbolic victories. Still other branches break off, ending rights claims altogether.

We build on the typology first presented in Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010), the spirit of Albiston et al. (Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014), and work that pushes beyond the dispute pyramid (e.g., Chua Reference Chua2019) to conceptualize rights mobilization as social processes through which people define troubles partially or wholly in terms of rights and “claim entitlement” inside or outside the legal system (McCann Reference McCann2014: 249). In this sense, rights can have both “de jure” and “de facto” dimensions (Heimer and Tolman Reference Heimer and Tolman2021), and rights mobilization, like rights themselves, “emanates from ordinary social life, often independent from lawyers, judges and state officials” (McCann Reference McCann2014: 248). We distinguish three branches of rights mobilization as well as the absence of mobilization (or doing nothing), as shown in Figure 1: legal mobilization, which involves litigation, formal administrative channels (e.g., the EEOC), or beginning these processes by contacting a lawyer; quasilegal mobilization, which involves internal complaint procedures provided by an organization or union, or alternative dispute resolution such as mediation; and extralegal mobilization, in which people act outside the legal system to express grievances and claim rights in some way.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of rights mobilization as multidimensional.

Law and society scholars have devoted the most attention to legal mobilization. It involves the greatest procedural formality, incurs the greatest temporal and financial costs, and yields a limited range of possible outcomes (Albiston Reference Albiston1999; Buckel et al. Reference Buckel, Pichl and Vestena2024; Clermont and Schwab Reference Clermont and Schwab2004; Felstiner et al. Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980-81; Galanter Reference Galanter1974; Lehoucq and Taylor Reference Lehoucq and Taylor2020; Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81; Mnookin and Kornhauser Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Nelson and Lancaster2010).

Quasilegal mobilization resembles aspects of legal mobilization in that aggrieved parties raise complaints and third-party decision-makers or facilitators to hear parties’ stories and either issue decisions or work with the parties toward negotiated results. Unlike legal mobilization, quasilegal mobilization typically does not occur in public forums and dramatically varies in its procedures (Harrington and Merry Reference Harrington and Engle Merry1988; Morrill and Rudes Reference Morrill and Rudes2010; Selznick Reference Selznick1969). Many large-scale organizations offer internal complaint procedures for their members and many require their members to agree to arbitration or mediation to avoid litigation (Calavita and Jenness Reference Calavita and Jenness2014; Dobbin Reference Dobbin2009; Edelman Reference Edelman2016; Krawiec Reference Krawiec2003; Talesh Reference Talesh2009). Quasilegal mobilization in school workplaces tends to consist of formal grievance, documentation, and appeals procedures provided by school administrations or unions (Stone and Colvin Reference Stone and Colvin2015).

Attention to quasilegal mobilization is important for multiple reasons. Legal scholars have long advocated for organizational self-governance as opposed to judicial resolution of disputes (e.g., Ayres and Braithwaite Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992; Bamberger Reference Bamberger2006; Estlund Reference Estlund2003). Yet, diverting claims from public legal forums can result in employers exercising greater control over both process and outcome (Edelman and Suchman Reference Edelman and Suchman1999; Talesh Reference Talesh2009). Organizational antidiscrimination policies and internal grievance procedures also help insulate organizations from civil rights liability because courts view organizational governance structures as indicators of fair governance and lack of discriminatory intent (Edelman Reference Edelman2016).

Extralegal mobilization looks little like legal mobilization, and can involve contacting third parties such as the media, therapists, or religious figures, discussing problems with friends or family, interpersonal confrontation, or praying. Such actions, often involving talk (Minow Reference Minow1987), can entail explicit or subtle articulations of rights, and blur the boundaries of what appear, for example, as coping or doing nothing. Extralegal action may help formulate and express grievances, can act as an intermediate step toward collective action, and/or quasilegal and legal mobilization, or, as Albiston et al. (Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014) argue, end further action. Illustrations of extralegal mobilization abound in the sociolegal literature (e.g., Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner1988; Black Reference Black1983; Reference Black1976; Cooney Reference Cooney1998; Reference Cooney2019; Ellickson Reference Ellickson1991; Emerson Reference Emerson2015; Engel Reference Engel1984; Reference Engel2016; Ewick and Silbey Reference Ewick and Silbey1998; Reference Ewick and Silbey2003; Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse1986; Kolb Reference Kolb, Kolb and Bartunek1992; Kolb and Bartunek Reference Kolb and Bartunek1992; Macaulay Reference Macaulay1963; McCann Reference McCann1994; Morrill Reference Morrill1991a; Reference Morrill1991b; Reference Morrill1995; Morrill et al. Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010; Morrill and Musheno Reference Morrill and Musheno2018; Nader and Todd Reference Nader and Todd1978; Tucker Reference Tucker1999; Yngvesson Reference Yngvesson1988).

The three types of mobilization (legal, quasilegal, and extralegal) can be pursued simultaneously, sequentially in any order, or combined. Mobilization of one form may resolve or yield a new understanding of the situation, which in turn results in a different type of mobilization or demobilization. Individuals also can respond to perceived rights violations by doing nothing (lumping it). However, we note that many actions that would have been considered doing nothing under the original dispute pyramid, such as prayer or talking with friends, are better understood as extralegal mobilization, or rights mobilization outside the legal order.

A gender system perspective on individual rights mobilization

We explore the relationships between rights mobilization and gender inequality through the lens of gender system theory. From this perspective, gender is an “institutionalized system of social practices” and underlying schemas based on stereotypical differences between two categories, men and women, that structure social inequality (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004: 510-14; see also, Acker Reference Acker2006; Connell Reference Connell, Hearn, Blagojević and Harrison2013). Gender inequalities related to the pervasive lower pay of women compared to men, enacting formal statuses, evaluating the actions of others, and perceiving obstacles for action can all be explained through the lens of gender systems theory (Abrams Reference Abrams1989; Bielby Reference Bielby, Nielsen and Nelson2001; Bielby and Baron Reference Bielby and Baron1986; Blau and Beller Reference Blau and Beller1988; England and Farkas Reference England and Farkas1986; Nelson and Bridges Reference Nelson and Bridges1999; Reskin Reference Reskin1984; Schultz and Petterson Reference Schultz and Petterson1992). Gender may even operate as a “cognitive” foundation on which other intersecting axes of inequality are built (Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004: 515).

Rights violations and mobilization

Previous research reveals that women are more likely than men to experience discrimination, sexual harassment, and violations of their right to due process in workplaces (Blackstone et al. Reference Blackstone, Uggen and McLaughlin2009; Chamberlain et al. Reference Chamberlain, Crowley, Tope and Hodson2008; Edelman and Cabrera Reference Edelman and Cabrera2020; MacKinnon Reference MacKinnon1979; Major and Kaiser Reference Major, Kaiser, Nielsen and Nelson2005). Because women are disproportionately responsible for childcare, they also are more likely to experience conflicts regarding leaves, absenteeism, and scheduling, as well as seniority issues that affect layoffs, promotion, and tenure (Albiston Reference Albiston2010; Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach Reference Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach1994; Nakamura and Edelman Reference Nakamura and Edelman2019).

Previous research also finds female employees engage in higher rates of extralegal compared to legal and quasilegal mobilization (Gruber Reference Gruber1989; Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach Reference Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach1992; Marshall Reference Marshall2003; Reference Marshall2005; Quinn Reference Quinn2000; Reskin and Padavic Reference Reskin and Padavic1988). Managers, for example, tend to discourage women from pursuing sexual harassment claims (Edelman et al. Reference Edelman, Erlanger and Lande1993; Marshall Reference Marshall2005) and women often perceive dispute handlers as inaccessible or hostile (Costello Reference Costello1985; Lewin Reference Lewin1987; Stanko Reference Stanko1985). Even in litigation, scholars find that traditional gender socialization conditions women to pursue less aggressive modes of dispute settlement (Bartlett Reference Bartlett1990; Burke and Collins Reference Burke and Collins2001; Charness and Gneezy Reference Charness and Gneezy2012; Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel, Grossman, Plott and Smith2008; Menkel-Meadow Reference Menkel-Meadow1985; Morgan Reference Morgan1999; Reingold Reference Reingold1996; Wofford Reference Wofford2017). From a gender systems perspective, we posit that female educators will be more likely than male educators to perceive violations of their own rights and less likely than male educators to be accused of violating the rights of others. We also hypothesize that female educators will be less likely than male educators to engage in legal and quasilegal mobilization, and more likely to engage in extralegal mobilization.

Law and organizations scholars have long argued that the managerial “‘haves’ come out ahead” and realize their advantages not only in litigation but also in quasilegal mobilization within organizations (Edelman and Suchman Reference Edelman and Suchman1999; see also, Albiston Reference Albiston1999; Galanter Reference Galanter1974; Krieger et al. Reference Krieger, Kahn Best and Edelman2015; Morrill Reference Morrill1995; Talesh Reference Talesh2012). We therefore posit that school administrators will be more likely than teachers to engage in quasilegal and formal legal mobilization. From a gender systems perspective, gender differences will tend to intensify status differences in mobilization.

Complaints and accusations

A vast literature addresses the powerlessness of the criminally accused, especially drawn from socially marginal groups (e.g., Clair Reference Clair2020; Feeley Reference Feeley1979; Kohler-Hausmann Reference Kohler-Hausmann2018; Natapoff Reference Natapoff2018; Skolnick Reference Skolnick1966; Van Cleve Reference Van Cleve2016). But there is very little research on the rights of individuals accused of civil wrongdoing, especially in workplaces (for exceptions, see Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite1988; Perrow Reference Perrow1999; Stone Reference Stone1975; Vaughan Reference Vaughan1996).Footnote 2 However, previous research provides some guidance in this regard. First, the law and economics scholars posit that the higher the stakes in a case, the more likely it is to be litigated (Posner Reference Posner1977: 436). Educators accused of wrongdoing may be more likely to engage in legal or quasilegal mobilization because they have more to lose financially or reputationally from any potential job loss, demotion, or other material penalties. Second, the pervasive legalization of schools means that the accused would have the right to contest their accusation through an internal complaint procedure (a form of quasilegal mobilization) or by filing their own action in court or an external administrative agency. Finally, accused educators may be more likely to hold administrative positions and thus face fewer obstacles in mobilizing quasilegal or legal mobilization to defend themselves. Considering these factors, we posit that educators accused of wrongdoing are more likely than educators with complaints to engage in formal legal and quasilegal mobilization. Here again, gender systems theory suggests that the extent to which accusations are lodged at male administrators will tend to intensify formal status differences.

Mobilization obstacles

When we move beyond the dispute pyramid to encompass not only legal but also quasilegal and extralegal mobilization, it is important to understand actors’ views of the obstacles they face in pursuing formal mobilization. As noted previously, one tradition in the literature emphasizes cost–benefit analyses focused on the seriousness of the stakes, and the costs of litigation, finding a lawyer, and information (Boyd Reference Boyd2015; Boyd and Hoffmann Reference Boyd and Hoffmann2013; Cooter and Ulen Reference Cooter and Ulen2016; Hylton Reference Hylton2002; Posner Reference Posner1977; Priest and Klein Reference Priest and Klein1984; Robbennolt Reference Robbennolt, Zamir and Teichman2014). Previous studies along these lines find women clearly understand the costs they bear by pursuing legal or quasilegal mobilization against men (Eckel and Grossman Reference Eckel, Grossman, Plott and Smith2008; Harris and Jenkins Reference Harris and Jenkins2006; Morgan Reference Morgan1999; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2004; Welsh Reference Welsh1999).

These research streams accurately characterize important factors underlying mobilization decisions, but elide normative considerations. Max Weber’s distinction between instrumental- and value-rational action is instructive here. Instrumental-rational action is oriented toward achieving purposes through “rationally pursued and calculated ends” (Weber Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1978: 24), whereas value-rational action is oriented toward upholding a “value for its own sake … independent of its prospects of success” (Weber Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1978: 25).

As both gender system and neo-institutional organizational theory make clear, cultural rules, moral principles, underlying schemas, and sacred symbols play important roles in workplace decision-making, even shaping how material costs are understood (Dobbin Reference Dobbin2009; Edelman Reference Edelman2016; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Edelman and Matusik2000; Heinz et al. Reference Heinz, Nelson, Sandefur and Laumann2005; March Reference March1988; Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977; Preiss et al. Reference Preiss, Arum, Edelman, Morrill and Tyson2016; Ridgeway and Correll Reference Ridgeway and Correll2004; Suchman Reference Suchman1995; Weinberg and Nielsen Reference Weinberg and Beth Nielsen2017). Law and rights are important not simply for the rules and sanctions they set forth but also because they provide meanings that imbue actions with positive or negative moral valences (Edelman and Suchman Reference Edelman and Suchman1997). When people perceive their rights violated or are accused of rights violations, how they respond occurs in the context of rational calculation and institutionalized normative ideas (Edelman Reference Edelman2016). Bumiller (Reference Bumiller1988), for example, shows that employees who suffer civil rights violations often choose not to mobilize their rights because they prefer to think of themselves as survivors rather than as victims. And Engel (Reference Engel1984) found that norms of personal responsibility and self-sufficiency discouraged rural Illinois community members from filing personal injury claims. Moreover, the identification of barriers for one type of mobilization may facilitate another type. Disputants who believe their prayers are enough to affirm their rights, for example, may shift away from law and toward religion as a claiming mechanism.

With respect to gender, prior research pushes in multiple directions. Some scholars find that institutionalized masculine and feminine stereotypes condition women to self-censure their complaints in order to be seen (by men) as “team players” (Quinn Reference Quinn2000) rather than “trouble-makers” (Bumiller Reference Bumiller1988), to avoid retaliation (Stambaugh Reference Stambaugh1997), and to constrain legal mobilization (West Reference West1988). Other scholars argue that gender inequalities offer women justifications for invoking law against men (Merry Reference Merry1990). We therefore ask, what is the relationship between gender and citing instrumental and normative obstacles to legal and quasilegal mobilization? We do not find previous research on obstacles for mobilization by those accused compared to those complaining of rights violations in workplaces. As such, we ask what is the relationship between formal status, complaints and accusations, and citing instrumental and normative obstacles to legal and quasilegal mobilization?

Methods

Survey response rates, structure, and procedures

Harris Interactive recruited teachers and administrators in a national study on “rights in schools” in 2007 and 2008. Survey interviews averaged 19 minutes in length; honorariums were not offered. Teachers (23%) had higher response rates than administrators (10.5%).Footnote 3 Surveys measured respondents’ personal demographics, school characteristics, and whether they had been accused or complained of a rights violation involving (a) discrimination, (b) sexual harassment, (c) due process, or (d) freedom of expression/academic freedom. Interviewers then asked respondents who experienced one or more violations which they considered the most significant and how they responded. The surveys included an open-ended question that invited respondents to give a brief (1–2 sentences) oral description of the rights violation they selected as most significant to them. Harris interviewers coded respondent self-reported gender (male/female), ethnicity/race, and status (teacher/administrator).Footnote 4

Interviewers read to respondents a list of responses to rights violations of which the first item was “did nothing,” followed by 13 randomized items from which the respondent could choose as many as were relevant (Morrill et al. Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010). Extralegal items included (a) talked with my friends or family, (b) sought counseling from a mental health professional, (c) sought support in my religious community, (d) prayed over it, (e) avoided the person, (f) directly confronted the person, and (g) contacted the media. Quasilegal items included (a) used a formal grievance procedure provided by the administration, (b) used a formal grievance complaint procedure provided by the union, and (c) used alternative dispute resolution (mediation, peer counseling, etc.). Legal mobilization included (a) contacted a lawyer, (b) filed a formal grievance complaint with a government agency, and (c) filed a formal lawsuit. Respondents who had experienced a rights violation, but had not pursued quasilegal and/or legal mobilization, were presented with a list of 16 commonly cited instrumental (e.g., “wasn’t sure how to”) and normative (e.g., “not right to”) obstacles (e.g., Albiston et al. Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2008).

Survey analysis strategy

Quantitative analysis of the survey data involved a two-pronged approach. First, we conducted descriptive analyses, which yielded percentages of mobilization choices (do nothing or extralegal, quasilegal or legal) by gender, status, and complaint/accusation. In subsequent multivariate analyses, we estimated rates of mobilization among educators by complaint/accusation, gender, and status. We conducted separate multivariate logistic regressions for each type of mobilization because respondents could mobilize in multiple ways, thus modeling each type of mobilization and doing nothing separately. For each type of mobilization as well as doing nothing, we estimated a baseline model, including three covariates: complaint or accusation, gender (male or female), and the number of incidents (0–3) the respondent experienced. For the kind of incident, we used complaint as the omitted category. Subsequent models add status (teacher or administrator). Our second set of descriptive analyses explored the associations among gender, status, accusation/complaint, and the instrumental and normative obstacles educators identify for not engaging in quasi- or legal mobilization. Significance levels for descriptive analyses are calculated using ANOVA pairwise comparisons, employing Dunnett’s post hoc estimation.

Qualitative data analysis of the open-ended descriptions of rights violations involved indexing the descriptions (which ranged in length from 17 to 47 words) according to the eight categories of rights violations in the survey instrument (complaints or accusations about discrimination, sexual harassment, due process, or freedom of expression/academic freedom). Of the 304 respondents who offered descriptions of their most significant rights violations (87% of the 348 respondents who reported at least one rights violation), 295 descriptions could be keyed to the rights violations they chose. The remaining nine descriptions were unintelligible. This procedure yielded a useful inventory and count of descriptions of the eight rights violations collected via the national survey.

In-depth interview protocols and analysis strategy

In-depth interview data derive from school-based, ethnographic case studies completed in five schools during 2008 (Morrill et al. Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010). In New York and California, respectively, we conducted interviews in four schools – two that serve upper-/middle-income populations and two that serve lower-income populations. In North Carolina, we conducted interviews at an upper-/middle-income school only. We recognize that the qualitative data are not nationally representative, yet can offer insights into the patterns identified in the surveys.

Socially diverse teams of graduate and undergraduate students led by three of the five authors conducted the interviews. We purposively selected participants to represent the demographics and diverse experiences of staff on each campus. Among the teachers interviewed, 23 identified as women, 10 as men, and 3 as nonbinary. Among the administrators interviewed, six identified as men and three as women. Note that the relative gender distributions of teachers and administrators identifying as male and female in our national sample survey and in-depth interviews approximate national distributions at the time of data collection.

Each interview lasted 45–90 minutes, was taped, and contained a tripartite structure: An opening section covered personal work history and impressions of their campus student body. A second section focused on problems and disputes encountered at school (including the most “significant”), and campus rules and rights. A final part explored administrative and union relations in teacher interviews, and union and district relations in administrator interviews. The interview structure thus combined techniques used effectively in other studies of school disputing (e.g., Morrill and Musheno Reference Morrill and Musheno2018), but with greater attention to rules and rights (Arum Reference Arum2003; Edelman Reference Edelman2016).

In-depth interview data analysis proceeded in three phases, which align with strategies that are increasingly becoming standard among qualitative social scientists. First, SRP research team members (the four faculty authors of this paper plus the graduate and undergraduate students then working on the team) began preparing for analysis while still conducting interviews through shared analytic (email) memos, phone conversations, and regular group meetings (Rubin Reference Rubin2021: 182–183). These initial forays into the data gave way to the team reading through the interview transcripts as an entire “‘data set’” (Emerson et al. Reference Emerson, Fretz and Shaw2011) across the three regions of the study (California, New York, and North Carolina). Our second phase in the coding process resonates with what Deterding and Waters (Reference Deterding and Waters2021) call “flexible coding,” which is particularly useful for team-based qualitative analysis of 30 or more in-depth interviews (recall that our data set comprised of 45 in-depth interviews). At team meetings and supported by the use of Atlas.ti, we pushed beyond our initial discussions and readings of the transcripts to anchor a master codebook to qualitative interview protocols and the rights violation and mobilization categories in the national survey, along the way developing operational definitions for each coding category. We then selected a number of representative interview transcripts from each region, applied the master codebook to them, and discussed the results to revise operational definitions, when necessary, and come to consistent (reliable) understandings of each code. Each regional research team then coded their own transcripts, which enabled the efficient processing of hundreds of transcript pages, reduced the amount of data each team analyzed, and provided the opportunity for each team to generate additional thematic codes. Once each regional team coded their own transcripts, the team as a whole came back together to discuss construct validity across the codes, various “aha’s” each team generated from its regional data sets, and whether regional thematic codes should be applied to other regions. A third pass through the data for the purposes of this paper involved “selective” coding (Corbin and Strauss Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) to explore the micro-dynamics of how teachers and administrators understand and chose to mobilize their rights in response to situations they define as rights violations. Unless otherwise noted, transcript excerpts appearing in subsequent sections represent broader patterns found in the interviews.

Survey sample characteristics

As shown in Table 1, most national survey respondents identify as female (55.81%) and White (87.23%). The ethnic/racial composition of the sample limited our ability to use this variable in our analyses, but is close to national percentages. Most teachers in the sample identify as female (70.00%), most administrators as men (72.10%), and nearly all in the sample (93.0%) work in public schools. More than half the sample (57.81%) reported rights complaints, accusations, or both.Footnote 5 In response to a complaint or accusation, most respondents (86.5%) reported taking extralegal action, more than half reported taking quasilegal action (50.9%), nearly one-fifth resorted to legal mobilization (18.6%), and few did nothing (11.4%). All subsequent tables, except Table 2, contain weighed values to estimate population parameters.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (national survey)

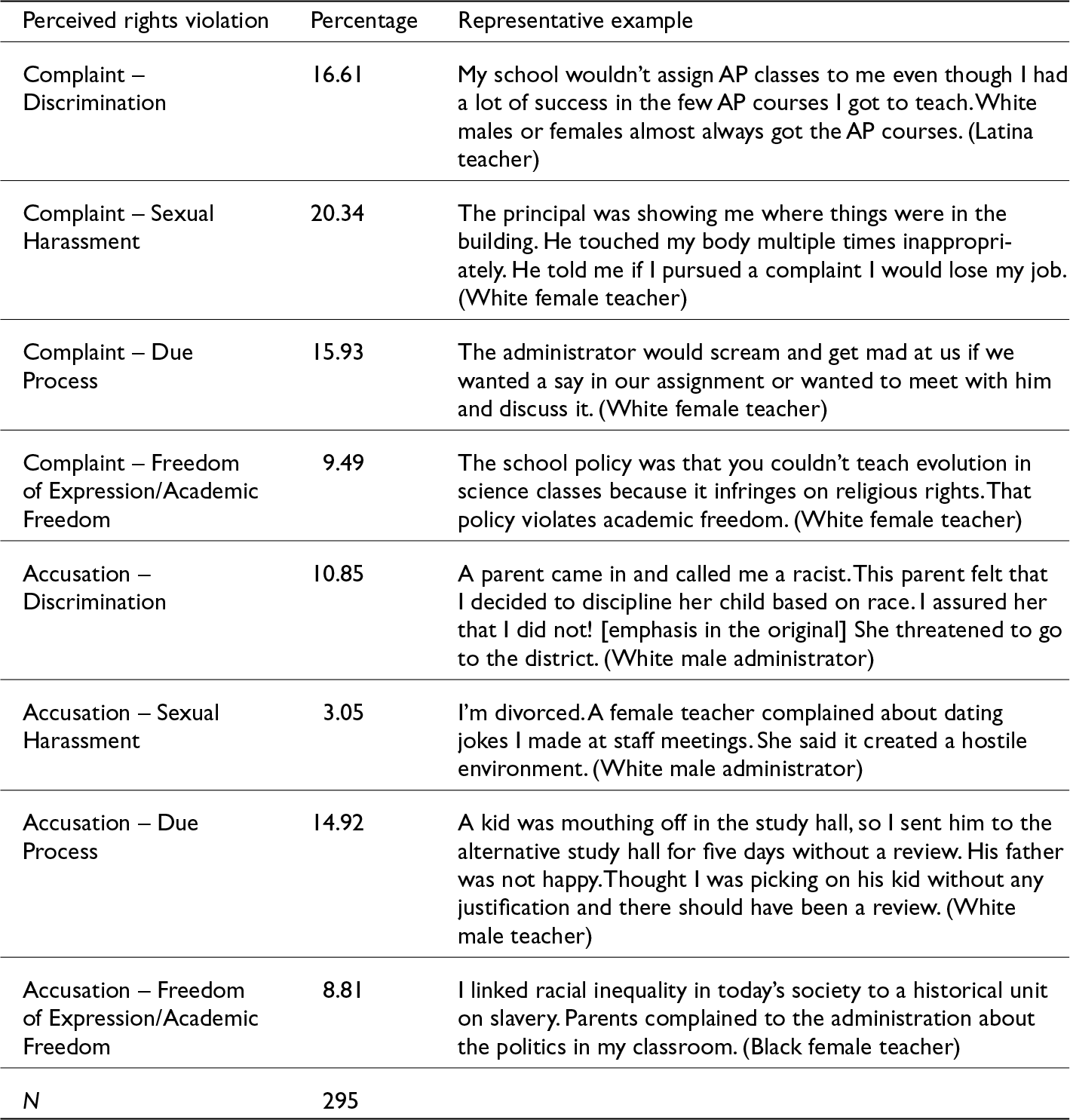

Table 2. Oral descriptions of perceived rights violations (national survey)

Rights dynamics in school workplaces

Respondent descriptions of rights violations

The distribution and examples of rights violations described by respondents in the national survey appear in Table 2. Respondents most often report rights violations involving sexual harassment (20.34%), followed by discrimination (16.61%), due process (15.93%) and freedom of expression/academic freedom (9.49%). Sexual harassment complaints include descriptions of, for example, unwanted physical encounters (as in the sexual harassment complaint example in Table 2), “stalking,” “leering,” and the creation of “hostile” or “unsafe” workplace environments through “lewd jokes,” “denigrating discussions,” and other actions. Just over three-quarters of the sexual harassment complaints come from respondents who identify as female and just over half are directed at male administrators. Discrimination complaints focus on hiring, promotion, and teaching assignments with racial or sexual discrimination mentioned most often (similar to the discrimination example in Table 2). Descriptions of due process complaints involve decision-making by administrators or peers outside standard procedures (but do not involve mentions of discrimination or harassment). Finally, almost all complaint descriptions about freedom of expression/academic freedom focus on policies and/or administrators that forbid the teaching of “evolution” or subjects related to race with a few exceptions, such as teaching “Christianity as an ideology.”

Accusation descriptions most commonly involve due process (14.92%), followed by discrimination (10.85%), academic freedom/freedom of expression (8.81%), and sexual harassment (3.05%). Due process accusations most commonly focus on student discipline in which parents and/or students claim that a punishment they receive is “unfair,” “unjustified,” or does not follow required procedures (as in the accusation due process example in Table 2). Freedom of expression/academic freedom accusations take one of two forms: (1) teacher accusations of administrators for violating their rights to teach a particular topic within their classes, express themselves in class on particular subjects, or facilitate particular extracurricular activities by students or (2) parents accusing teachers of teaching particular subjects that either make their classrooms too “political” (as in the freedom of expression/academic freedom accusation example in Table 2) or violate their rights (as parents) in some way. In the latter instance, such accusations also become the basis for complaints by teachers (as in the freedom of expression/academic freedom complaint example in Table 2). Finally, the least described rights accusation, sexual harassment, was also the most described complaint. This pattern suggests a potentially hidden layer of accusations involving sexual harassment unreported by survey respondents.

Table 3, based on the national survey, offers initial support for our hypotheses that female educators will be more likely than male educators, and that teachers will be more likely than administrators, to perceive their own rights being violated. Nearly three times as many female (28.87%; p< 0.01) as male (10.15%; p< 0.01) educators, and nearly three times as many teachers (26.62%; p< 0.01) as administrators (8.50%; p< 0.01) report complaints about their rights being violated. These data also support our hypotheses regarding gender, status, and accusations. Twice as many male (22.93%; p< 0.01) as female (9.23%; p< 0.01) educators report being accused of violating the rights of others, and three times the number of administrators (29.00%; p< 0.01) as teachers (8.46%; p< 0.01) report accusations. In terms of complaints, female teachers (31.38%; p< 0.01) report the most complaints, while female administrators (22.01%; p< 0.05) look similar to male teachers (21.33%; p> 0.1) and quite dissimilar to male administrators (5.99%; p< 0.01). In terms of accusations, male administrators (38.66%; p< 0.01) experience the highest rate, followed by female administrators (11.21%; p< 0.01), female teachers (8.08%; p< 0.01), and male teachers (7.99%; p< 0.01).

Table 3. Complaints and accusations by gender and formal status (national survey)

a Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is males.

b Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is principals.

c Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is male principals.

Note: Significant differences in rights incidents between groups are noted with asterisks next to estimates.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Rights mobilization

In Table 4 (also based on the national survey), we see partial support for our hypothesis that female educators will be less likely than male educators to engage in formal or quasilegal mobilization in response to any rights incident, and more likely to engage in extra-legal mobilization. We also see partial support for our hypothesis that administrators will be more likely than teachers to engage in formal or quasilegal mobilization, and less likely to engage in extra-legal mobilization. More teachers (8.98%; p< 0.05) compared to administrators (1.62%; p< 0.05) report doing nothing, and more administrators (59.76%; p< 0.1) compared to teachers (47.37%; p< 0.1) report taking quasilegal action. At the same time, more male teachers (15.39%; p< 0.01) than male administrators (0.74%; p< 0.01) report doing nothing and fewer male teachers (75.69%; p< 0.05) than male administrators (89.42%; p< 0.05) report taking extralegal action.

Table 4. Mobilization by gender and formal status (national survey)

Note: Significant differences in perceived rights violations between groups are noted with asterisks next to estimates.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

a Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is males.

b Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is principals.

c Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The comparison group is male principals.

Given these patterns and that 86% of educators report extralegal mobilization, it is important to consider what these actions look like. The most common extralegal mobilization involves talking with friends and family (67.34%). Although talking with others may not, at first blush, appear to be rights mobilization, it can function as a form of “rights talk,” which can promote rights awareness, change social thinking, and even facilitate social movements (Cover Reference Cover1983; Lovell Reference Lovell2012; Merry Reference Merry2003; Minow Reference Minow1987; Polletta Reference Polletta2000). Friends and family members may even act as “agents of transformation” to encourage other forms of mobilization (Felstiner et al. Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980-81).

Although we did not find statistically significant differences among specific modes of extralegal mobilization with respect to status or complaints compared to accusations, there were multiple associations with gender. More female (76.67%; p< 0.05) than male (59.50%; p< 0.05) educators report talking with friends and family, and more female (24.39%; p< 0.1) than male (15.95%; p< 0.1) educators report avoiding an offending person. Conversely, more male (55.51%; p< 0.1) than female (42.03%; p< 0.1) educators report confronting an offending party. This overall pattern resonates with research finding that women pursue their own workplace complaints in nonconfrontational ways (Amanatullah and Morris Reference Amanatullah and Morris2010; Kolb Reference Kolb, Kolb and Bartunek1992).

Over a quarter (26.82%) of educators in the national sample report praying when they experience a rights incident. While some previous research characterizes praying as a mechanism to avoid confrontation or define a rights violation out of existence while waiting for divine intervention (Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse1986; Nader Reference Nader1988), our results suggest that praying is used with other forms of extralegal mobilization. Among respondents who report their prayers were a reason for not pursuing a complaint via legal or quasilegal mobilization, more than half (56.00%) report confronting the offending party and the vast majority (80.12%) report speaking with other people. Rather than a mechanism that suppresses mobilization, praying may actually be a contemplative process informing other choices that a person makes concurrently or later in rights mobilization.

Multivariate analyses: gender, status, and complaints and accusations

We now turn to multivariate analyses to assess the relative effects of gender, status, and complaints compared to accusations. Table 5 (based on the national survey) contains multivariate models that estimate educators’ mobilization choices. The models in Table 5 include the following independent variables: a dummy variable for whether the educator reports an accusation (which we compare to the omitted category, educators who report only complaints), and dummy variables representing gender by status combinations: male administrators (omitted), female administrators, female teachers and male teachers.Footnote 6 For ease of interpretation, we estimate and report predicted margins as percentages rather than log odds. The percentages reported below are based on the full model for the dependent variable: Model 2 for doing nothing, Model 4 for extralegal mobilization, Model 6 for quasilegal mobilization, and Model 8 for legal mobilization.

Table 5. Rights mobilization logistic regression results (national survey)

Standard errors in parentheses.

a Relative to respondents who experienced complaints only.

b Relative to respondents who experienced complaints only.

Note: Significant differences in mobilization between groups are noted with asterisks next to estimates.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The multivariate analyses provide some support for our hypotheses. Teachers (11.41%; p< 0.01) are more likely than administrators (3.04%; p< 0.01) to report doing nothing (Model 2). Female administrators are more likely (4.89%; p< 0.1) than male administrators (0.6%; p< 0.1) to report doing nothing, yet are less likely to do so than male teachers (16.84%; p< 0.1) or female teachers (7.38%; p< 0.1). Male educators (11.10%; p< 0.05) are more likely than female educators (6.45%; p< 0.05) to report doing nothing in response rights incidents. Most teachers and administrators, then, report mobilizing their rights in some way, but male teachers are the most likely group to take no action at all, although female administrators look more similar to female teachers than male administrators in their mobilization choices.

Consistent with our gender hypothesis, female (88.32%; p< 0.1) compared to male (79.55%; p< 0.1) educators are more likely to report using extralegal mobilization. Contrary to our hypothesis regarding status, administrators (92.41%; p< 0.05) compared to teachers (79.85%; p< 0.05) are more likely to report using extralegal mobilization (Model 4).

Model 6 (quasilegal mobilization) and Model 8 (legal mobilization) lend some support to our hypothesis regarding the accused being more likely than complainants to use quasilegal or legal mobilization. Educators reporting accusations only are more likely (24.72%; p< 0.05) than educators reporting complaints only (10.00%; p< 0.05) to engage in legal mobilization. Educators reporting complaints and accusations (which comprised 21.50% of respondents reporting any rights violation) also are more likely (58.03%; p< 0.05) than educators reporting only complaints (42.01%; p< 0.05) to use quasilegal mobilization. Nearly the same pattern can be seen for educators reporting both a complaint and accusation in that they are more likely (23.17%; p< 0.01) than respondents with a complaint only (10.02%; p< 0.01) to mobilize law.

Our qualitative data from the regional in-depth interview study shed additional light on the survey results. A California administrator, who identifies as “a White woman” with a decade of teaching and administrative experience, responded to questions about trouble with teachers and other administrators:

Administrator: Teachers have accused me of treating them unfairly because I don’t get their culture or I’m violating their rights. Which is code for race.

Interviewer: What do you do in that situation?

Administrator: I prefer talking with them first, keep it from escalating. But I use the procedures too; protect myself.…. At the school where I [taught], I had trouble with a principal. He was stalking me.

Interviewer: What did you do?

Administrator: I thought about filing a grievance. I knew if I did nothing would happen. So, I left. That was one of the reasons I wanted to become an administrator. I have a right not to be subject to that to that kind of behavior.

A North Carolina administrator, who identifies as “White” and “male” with a decade of administrative experience, responded to similar questions:

I’ve had teachers accuse me of unfairness.… [E]ven before it escalates, you need to be ready with protocol, with the procedures. So important to document so if you need to you can lean into protocol, the system.…. Make sure your rights are in play. With assistant principals, you can have philosophical differences, sometimes male-female problems, then you’re in trouble. We have to be able to discuss things. It’s different with administrators than with teachers. We [administrators] have to be able to get behind closed doors and hammer it out.

A third set of comments from a New York administrator, who identifies as a “Black man” with “several years” of administrative experience, touches upon formal accusations:

If you’re getting sued or grieved, of course you need to lawyer up, but you might have to use the system anyway before that. You’ve got to think ahead. Keep your head about you, but not necessarily tip your hand. As [an administrator], I’ve been involved multiple times in these kinds of situations and I know people and I know how the system works, so I can lean into my rights.

Legalized aspects of school workplaces – including “procedures,” “protocol,” and the “system” – loom large in these examples. The California administrator recounts teachers accusing her of treating them “unfairly” and “violating their rights,” adding that such accusations may be “code for race” and by implication, a basis of racial discrimination. She prefers extralegal responses (“to talk”) as a means of de-escalation, but also notes she will use “procedures” to “protect” herself. She also tells about a principal “stalking” her as a teacher, yet she did not “file a grievance” (presumably for sexual harassment), instead moving to administration as a form of exit (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970; Morrill Reference Morrill1995), stemming from her sense of having a “right not to be subject to that kind of behavior [harassment].”

The North Carolina administrator appears ready at the drop of a hat to mobilize formal processes, yet draws a distinction with respect to status – teachers (“you document in the system”) compared to administrators (“get behind closed doors”). The New York administrator underscores his experience as a “repeat player” (Galanter Reference Galanter1974; “involved multiple times in these kinds of situations”) while holding out the possibility that he could “talk to whoever it is” with whom he is in conflict (similar to the California female administrator). Yet, he admits that if he faces legal accusations, he would “need to lawyer up” and “lean into [his] rights.” At the same time, he touts his social capital (Portes Reference Portes1998; e.g., “know people”) and repeat-player knowledge (“know how the system works”) in responding to accusations while affirming his rights (“lean into my rights”).

These examples underscore the decision to invoke quasi- or legal mobilization as a process, contingent upon who accuses whom (e.g., a teacher or an administrator) and how they do so. The examples also suggest how those in power think about anticipatory mobilization (e.g., “You’ve got to think ahead”) with respect to quasi- and/or legal mobilization as a means to fend off future informal and formal accusations. Anticipatory mobilization refers to a sense that one must be ready for or even knows that some type of formal mobilization and escalation will occur. Administrators appear conscious that the highly legalized context of school workplaces can transform any claim into a formal accusation and thus they need to be ready with their own formal mobilization in response or even prior to a more formal accusation being made.

Anticipatory mobilization is a stance that administrators in our study believe will enhance their defense in the wake of accusations by helping establish their version of the events at issue or because it helps them assess and manage potential legal risks. Our survey and in-depth interview data reveal some instances in which potential accusers had their jobs threatened by harassers (e.g., the sexual harassment complaint example in Table 2), but did not reveal situations in which administrators overtly threatened teachers with the threat of formal mobilization. In this sense, anticipatory mobilization may be as much about keeping an accuser guessing about what the next move a manager might make as it is about propping up a manager’s sense of self efficacy. Could anticipatory mobilization also be used by less powerful claimants? Our data did not reveal this pattern, although one could imagine its use in this way, especially in highly legalized school workplaces or contexts of heightened rights consciousness and mobilization.

Mobilization obstacles

Table 6 (based on the national survey) contains the percentages of educators who report instrumental or normative obstacles constraining quasi- or legal mobilization by gender and status alone, and then by the intersection of gender and status. Women cite both instrumental and normative obstacles at greater rates than men. Their instrumental obstacles include: a supervisor advised me not to (6.67% compared to 0.56%; p < 0.05), someone (not a supervisor or lawyer) advised me not to so (8.42% compared to 2.84%; p < 0.1), feared retaliation (16.28% compared to 3.05%; p < 0.01), wasn’t sure how to (8.26% compared to 0.81%; p < 0.01), and wouldn’t do any good (34.04% compared to 14.37%; p < 0.01). This pattern fits with previous research on the instrumental obstacles women face in workplace mobilization, especially in the context of sexual harassment, including supervisors discouraging women from seeing sexual harassment as a serious problem meriting formal mobilization (Marshall Reference Marshall2003; Reference Marshall2005), the fear of retribution from quasilegal or legal mobilization (Morgan Reference Morgan1999; Wofford Reference Wofford2017), and knowledge that formal claims rarely succeed (Berrey et al. Reference Berrey, Nelson and Beth Nielsen2017). Female educators also cite a range of normative obstacles to formal mobilization at greater rates than men, including would harm a work relationship (18.25% compared to 6.09%; p < 0.01), didn’t want to cause a fuss (27.63% compared to 6.59%; p < 0.01), should handle own problems (42.40% compared to 24.39%; p < 0.01), and religious beliefs prevented it (3.35% compared to 0.00%; p < 0.01). The first two findings, in particular, align with previous research that reveals women more often than men try to uphold values of “interpersonal harmony” (Morgan Reference Morgan1999: 88) and handling one’s own problems (Engel Reference Engel2016).

Table 6. Obstacles to using legal or quasilegal mobilization by gender and formal authority (national survey)

Notes: Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The omitted category is Male Principals.

Significant differences between groups are noted by asterisks.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

With respect to status, the pattern is nearly the same as for gender in that teachers and women cite an almost identical set of instrumental and normative obstacles. This finding is not surprising given the intertwining of gender and formal status in school workplaces at the time of data collection. The one exception is knowing someone who had a bad experience, which teachers (9.79%; p < 0.01) cite more often than administrators (1.17%; p < 0.01). This pattern suggests that much of what may be driving female–male differences comes from the female–male administrator difference.

Turning explicitly to the intersection of gender and status, we see much of the same pattern as with female educators: female compared to male teachers are more likely to identify both instrumental and normative obstacles to engaging in quasilegal or legal mobilization. By contrast, there are few statistically significant differences between female and male administrators in terms of obstacles identified, save for more female (33.89%; p< 0.1) than male (6.10%; p< 0.1) administrators not wanting to cause a fuss by engaging in quasilegal or legal mobilization and more female (23.35% p< 0.01) than male (0.00% p< 0.01) administrators not knowing how to engage in quasilegal or legal mobilization. In addition to offering more normative and instrumental rationales for their decisions not to mobilize formally, female administrators look more like female teachers in terms of the obstacles they identify for not engaging in quasilegal or legal mobilization. By contrast, male administrators identify fewer obstacles that would constrain them from engaging in legal mobilization.

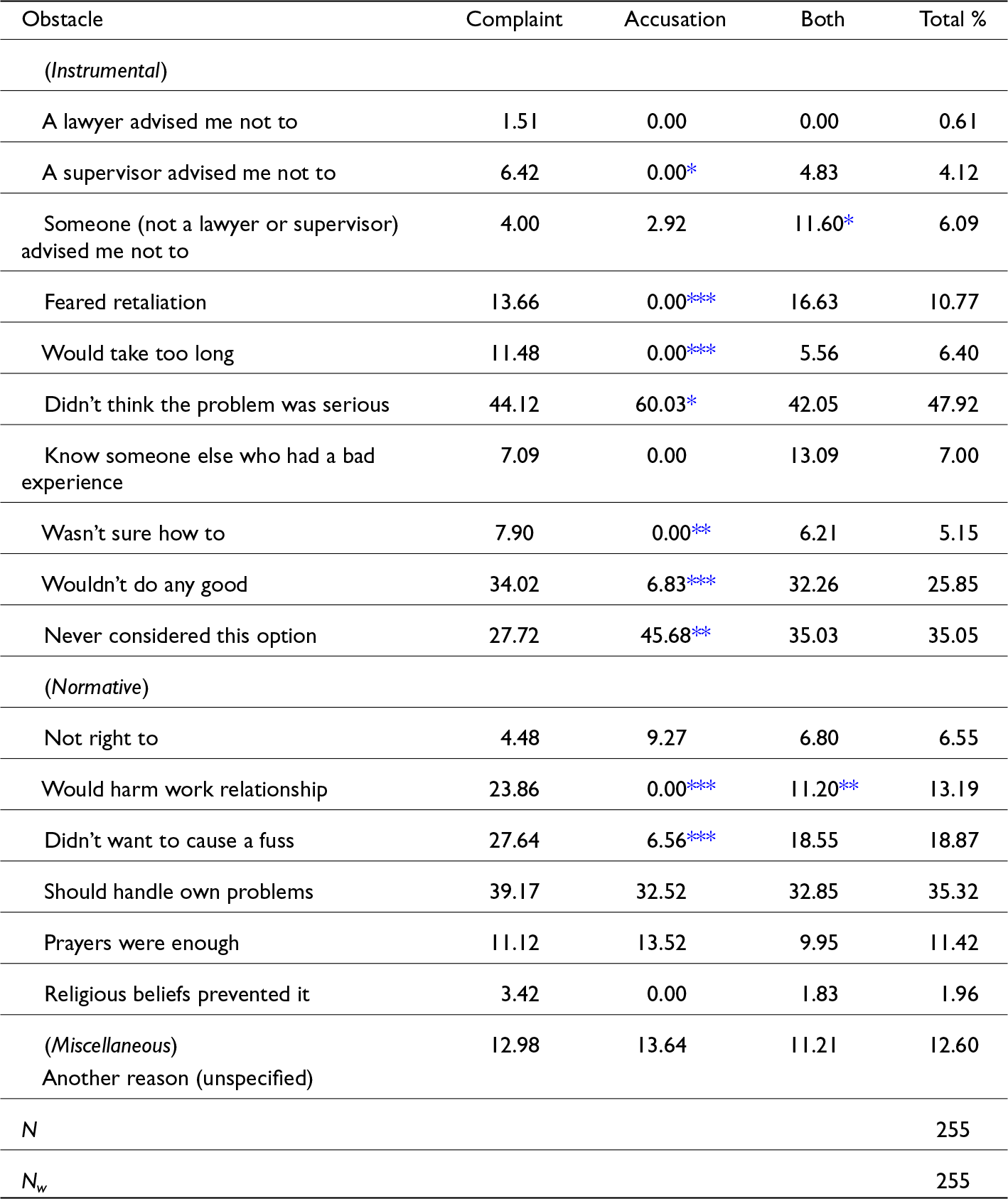

In Table 7 (based on the national survey data), we see the obstacles to quasilegal and legal mobilization by educators with complaints, those accused of rights violations, or both. Overall, those who are accused reported far fewer obstacles constraining quasilegal or legal mobilization with two exceptions. The accused are more likely than complainants to think the problem was not serious (60.0% compared to 44.12%; p< .1) and more likely to have never considered formal mobilization (45.68% compared to 27.72%; p< .05). These last differences appear to contradict our earlier finding that those accused of rights violations are more likely than those with complaints only to lean into quasilegal and legal mobilization.

Table 7. Obstacles to using legal or quasilegal mobilization by complaint, accusation or both (national survey)

Notes: Significance levels are reported from pairwise comparison of means with Dunnett’s test. The omitted category is Complaint.

Significant differences between groups are noted by asterisks.

* p< 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Here again, our in-depth interviews provide additional insight. A California teacher with more than two decades teaching experience identified as an “African American woman” and recounted this episode in response to questions about trouble with administrators:

Teacher: I [had] an issue with a [female] student earlier this year…. I wrote her up a couple of times.… [W]e had a meeting with the vice principal.…. He had her begin. Total fabrication…. Then I’m talking and the student raised her hand in my face. I’m thinking this is going to be a totally unproductive meeting … [because the vice principal] allows the student way too much control. It’s not a, “he said, she said.” The vice principal says, “The problem is, you’re just two strong women.” And I’m thinking, she isn’t a woman, she’s a 14-year old girl. The meeting ended with nothing resolved, but I needed to settle down. I’m thinking, I can’t write anything right now. I’ll say something I don’t want to say. I gave myself twenty-four hours to think how do I want to put this in writing. Pray over it a bit.…. I wrote him an email that we’ve always had a good relationship, you’ve always supported me with any issue with a student, and I really feel like yesterday’s meeting was unfair…. I’ve had male colleagues in that exact situation and he supports the teacher. This is sex discrimination.

Interviewer: Did you think about filing something formal against the administrator?

Teacher: If I do that, nothing happens except he’s pissed at me. Not sure where that might go. Plus, I have a solid relationship with him. And he knew what he did. He finally acknowledged I was correct, and [the student] was placed on contract [probation]. Things were fine after that, sort of.

A New York teacher who identified as “White” and “female” narrated an incident in response to our questions about trouble with administrators:

Teacher: …[A] student was publishing a [club] newsletter and he was inserting it into the [school] newspaper…. The principal wasn’t happy about this so she came to me first … since I was moderating the club.… [S]he didn’t want this newsletter to be out…. The student published another newsletter and then the principal was furious with me.

Interviewer: Why was she so disturbed by it?

Teacher: She tried to make it a budgetary thing. The newsletter was for the Gay-Straight Alliance and talked about ways of coming out.…. I think she felt uncomfortable with that being in the paper.…. I felt that the club was within its rights. There is a free speech issue for me, but I’m also realistic that this takes place in the context of the school. It’s not a union issue, but I thought about going to the district. The school newspaper has funding from the parents’ association. They’re an important constituency. I have to respect my principal’s beliefs about what’s she comfortable having in public and what she’s not. She knows the issues. I talked with her privately about the situation, but in a non-threatening way so that I didn’t bring up the free speech issue explicitly.

Interviewer: What happened the second time after [the newsletter came out]?

Teacher: [The principal] talked to the student. She was really trying to work on him. [She told him] we don’t have the funding for it. I don’t know what happened after that.

Both of these teachers identify particular rights violations – “sex discrimination” in the California teacher’s words and “free speech issue” from the New York teacher’s perspective – at the core of their accounts. In each instance, the teachers engage in extralegal rights mobilization. The California teacher “pray[ed] on it” and then wrote an email accusing her vice principal of being “unfair,” stressing his professional support for her (“always supported me”) while not claiming sex discrimination. The New York teacher spoke “privately” with her principal, but did not raise the issue of freedom of expression (“didn’t bring up the free speech issue explicitly”).

These and other examples from our in-depth interviews illustrate the often-ambiguous boundaries between doing nothing (lumping) and extralegal mobilization. Both teachers name rights violations and blame an offending party in their own minds (and to the interviewer), yet fall short of explicitly making rights claims to that party (Felstiner et al. Reference Felstiner, Abel and Sarat1980-81). The recognition that they, as “selves,” have rights is, in part, “transformative” in how they interpret their own and others’ perspectives (Merry Reference Merry1990: 51–54; Reference Merry2014), especially their sense that the administrators are fully aware of the rights in play (e.g., “he knows” and “she knows the issues”). These fraught actions thus involve what could be called, rights muting. Ambiguity and self-censorship mark rights muting all while the rights violation in question remains clear in a complaining party’s mind as they approach an offending party and carefully self-regulate their emotions (e.g., “I needed to settle down”; on emotional self-regulation, see Grandley and Melloy Reference Grandley and Melloy2017). Less powerful parties use rights muting to protect themselves and, perhaps, to convince themselves they have pushed beyond doing nothing in response to a rights violation even as their actions may not lead to further mobilization. Moreover, social connections and positive affect, such as the relationship the California teacher cited with an administrator (“I have a solid relationship with him”) or the “respect” that the New York teacher had for her principal can act as “binding” forces to “postpone confrontations,” including rights claims (Merry Reference Merry1990: 95).

By contrast, administrators appear to balance their anticipation of potential trouble and using formal procedures with a sense they can informally handle trouble before it escalates. Their informal actions illustrate another aspect of rights muting. When accused or when they suspect they may be accused in the future, the powerful can use rights muting to try constraining the transformation of what appears to be an ambiguous hitch into an explicit rights claim by less powerful parties. Such actions both protect the more powerful party while attempting to suppress the possibility of further mobilization by less powerful parties. These latter dynamics thus resonate with previous findings about how organizational managers reframe claims of sexual harassment by female subordinates (Marshall Reference Marshall2003) or how male executives reframe potential discrimination claims by female subordinates (Morrill Reference Morrill1995). The different postures with regard to mobilization signal positionality in the gender system, especially as it intertwines with formal status.

These accounts also point to the mix of normative and instrumental constraints for not pursuing quasilegal and legal mobilization identified by female teachers in our national survey. Again, the California teacher raises the preservation of her “solid relationship” with her administrator and an instrumental concern that formal mobilization would not yield favorable results while increasing the possibility of retaliation (“Nothing will happen except he’s pissed at me. Not sure where that might go.”). The New York teacher considers going to the “district,” but raises instrumental and normative constraints, respectively, including running afoul of groups associated with the school’s extracurricular funding (“a certain constituency”) and, as noted above, “respect” for her principal’s “beliefs.”

Discussion and conclusion

Our quantitative survey findings suggest that rights mobilization in school workplaces integrally links with gender inequality. In particular, female principals’ mobilization choices look more like those of female teachers than male principals. We also find that educators accused of rights violations – more administrators than teachers – compared to those raising complaints about rights violations are more likely to access the power of quasilegal and legal mobilization. Female educators also cite more instrumental and normative obstacles to legal and quasilegal mobilization than male educators, which resonates with previous research on constraints to rights mobilization among women in the workplace. Our qualitative interview data paint a more nuanced portrait than our survey findings, and introduce two new concepts related to the complex micro-dynamics of rights mobilization – rights muting used by less powerful actors to protect themselves or used by more powerful actors to both protect themselves and suppress rights accusations against them, and anticipatory mobilization used by more powerful actors as they defend themselves against potential or actual accusations.

This paper also advances the rights mobilization literature in other ways. First, in contrast to dispute pyramid studies that privilege legal mobilization (e.g., Clermont and Schwab Reference Clermont and Schwab2004; Reference Clermont and Schwab2009; Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Nelson and Lancaster2010), our study illustrates the multidimensional nature of rights mobilization in and outside the legal system. Whereas the dispute pyramid emphasizes the prevalence of “lumping it” (Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81), we show that among educators, only a tiny fraction really do nothing in response to the rights violations they perceive while a majority engage in extralegal mobilization.

More importantly, we offer the first analysis of rights mobilization that considers not only those who believe their rights have been violated but also those who are accused of violating others’ rights. Especially in the context of gender inequality and legalization in organizations, this is a critical distinction: rights mobilization of any kind among employees is low (Bumiller Reference Bumiller1988; Miller and Sarat Reference Miller and Sarat1980-81; Nielsen et al. Reference Nielsen, Nelson and Lancaster2010), but our research identifies how employees mobilize rights and the obstacles they face. We show that educators are significantly more likely to avail themselves of legal and quasilegal mobilization when they are accused of wrongdoing (especially as administrators) than when they complain about their own rights being violated. Educators accused of wrongdoing (especially those in more powerful positions vis-à-vis those who are complaining against them) are more likely to mount or anticipate mounting a defense via quasilegal and legal mobilization than educators with complaints about rights violations, perhaps because their employment status is at stake or the formality of the accusations means they cannot mount a defense without a formal response. That those accused lean into formal mechanisms may therefore be a function of legalization, which itself may confer advantages on organizational “haves” (in school workplaces, administrators). Moreover, it also matters that female administrators look more like female teachers than male administrators in their rights mobilization, which disadvantages them in defending themselves. Gender may constrain rights mobilization by women even in higher formal status roles in schools, echoing much of what happens in the corporate world (Edelman Reference Edelman2016).

The three most common obstacles educators identify in our survey data are instrumental (the seriousness of the issue and not considering more formal mechanisms) and normative (one should handle one’s own problems). Women, however, identify more instrumental (e.g., fear of retaliation) and normative (e.g., would harm relationships, make a fuss) obstacles than men. This pattern not only aligns with earlier research (e.g., Marshall Reference Marshall2005; Morgan Reference Morgan1999; Quinn Reference Quinn2000) but also suggests that women understand they are caught in a web of barriers to formal rights mobilization comprised of both calculated risks and principled concerns. Our interview data show how women constantly balance these constraints via rights muting during situations they perceive as rights violations and as they reflect on potential mobilization choices. Parallel to our survey results, male administrators in interviews primarily acknowledge instrumental considerations as they anticipate using formal mobilization.

Our survey data show that the three most common types of extralegal mobilization are talking with friends or family, verbal confrontation, and prayer. Our interview data suggest, however, that rights complaints to higher-ups can involve rights muting fraught with ambiguity. Previous research finds that in nonhierarchical workplaces women more often than men turn to formal mobilization because the former lack access to social networks needed to settle disputes informally (Hoffman Reference Hoffman2005). Future research needs to investigate gender inequality and extralegal mobilization, including the conditions under which it occurs, can lead to rights recognition and more formal modes of mobilization, or elides rights altogether.

Similarly, the relative prevalence of prayer as a form of extralegal mobilization should be taken seriously. Over a quarter of the respondents in our national sample engage in prayer as a form of mobilization and nearly one-fifth of the most religious educators cite “prayers were enough” as a reason for not using more formal modes of mobilization. Interestingly, we found that educators with both complaints and accusations were more likely to turn to prayer than those who experienced one or the other. It may be that these educators felt greater despair over their situation. As with other forms of extralegal mobilization, further research into the perceived benefits of using prayer might lend insight into how it offers an alternative to law as a means of rights mobilization.

We also recognize various limitations in our study, most importantly that the age of our data may limit its generalizability. Data collection for this project occurred during an era when public debates about K-12 public education centered on standardized test scores to reward or punish schools with respect to student achievement (e.g., “No Child Left Behind” policies), the expansion of school choice, and school securitization (Kupchik Reference Kupchik2012; Ravitch Reference Ravitch2010). Over the past decade, the #MeToo and BLM movements led to new debates by elevating rights consciousness about discrimination and sexual harassment, although recent studies question the lasting effects on workplaces of these movements (Alaggia and Wang Reference Alaggia and Wang2020; Kirk and Rovira Reference Kirk and Rovira2022). Debates persist about charter schools and standardized testing, social inequality, and securitization policies related to racial inequalities, on the one hand, and mass shootings in schools, on the other. Two dramatic changes, however, occurred since we collected the data for this project. The first change consists of a set of crisscrossing political changes. During the early 2020s, schools became flashpoints for political contestation over freedom of expression/academic freedom and sexual discrimination, including teaching race (with Critical Race Theory as a mythical object of contention) and recognizing LGBTQ+ rights (Teitelbaum Reference Teitelbaum2022). These dynamics heightened individual and collective rights mobilization that tend to privilege White middle-class voices, including “parents’ rights movements” aimed at influencing school boards and state legislatures (Stanford Reference Stanford2023), and federal civil rights cases charging public schools with antisemitism (e.g., Fensterwald Reference Fensterwald2024). Yet another change is a dramatic increase of public support for unions and a resurgence of union power amidst the beginnings of reconceptualizing the normative stakes of unionization (Reddy Reference Reddy2023). Whether or how these latter changes will translate into public educational contexts, which traditionally have been among the most unionized public sectors, is an open question. The second change is demographic. The national rate of secondary educators identifying as White continues to hover at 75% to 80% and the percentage of teachers identifying as female remains 70%–75% (depending upon the year), but the percentage of administrators identifying as female steadily increased from the low 40% range in the 2000s to 54% by 2021 (Taei and Lewis Reference Taei and Lewis2022).Footnote 7 Our data thus offer a benchmark for future studies of rights mobilization in school workplaces amidst these political and demographic changes.

There are multiple additional methodological limitations of this study. First, the lack of ethnic and racial variation in our sample precluded our analyses of these social characteristics. This limitation creates opportunities for future research to explore how the intersection of race, gender, and formal status matter in rights mobilization in American school workplaces. Second, although our binary measure of gender is reductionist, we suspect that the number of educators who identify as gender non-binary would not have been sufficient to alter our results. Third, our survey relies on retrospective accounts that are subject to various biases, such as selective recall. Fourth, our characterization of mobilization obstacles into an instrumental/normative binary is somewhat subjective and certain perceptions may in fact represent a combination of the two. Finally, because our survey employed a cross-sectional design, we are unable to account for the sequence of events or report the time intervals between the various incidents that respondents experience and their mobilization decisions. Thus, we cannot make causal claims.