Numerous previous studies have documented that racial resentment of blacks drives support for the death penalty at the individual level. White Americans with high levels of racial resentment are much more likely to support the death penalty compared to whites with more accepting racial attitudes toward blacks (e.g., Unnever and Cullen Reference Unnever and Cullen2007). These effects are distinct from general support for punitive policies or simple left-right political ideology. In this article, we move from the individual level to the aggregate level and show, using a cross-sectional time series approach, that states with higher aggregate levels of racial resentment impose more death sentences. Our article therefore moves the debate about racial attitudes and the death penalty from the realm of opinion into the realm of actual policy outputs.

There is no stronger demonstration of the power of the state than the decision to impose capital punishment. Many flaws and imperfections mar this system, causing the death penalty not to be focused on the “worst of the worst.” We review data on every death-penalty state in the nation from 1989 through 2017, the entire time for which relevant data are available, and show that, net of appropriate controls for institutional factors, crime, population, and general conservative ideology, racial resentment drives use of the death penalty.

Many authors have shown a close connection at the individual level between measures of racial resentment and support for punitive criminal justice policies, including specifically the death penalty. Our approach links these micro-level findings to two slightly different, but arguably more consequential, questions. First, when looking at the 50 states from year to year, do higher levels of racial resentment across the entire state population correspond with higher numbers of death sentences actually imposed? Second, is this effect stronger for black offenders than for whites? The results lead us to answer both questions in the affirmative.

We posit a historical legacy argument here as well. After first demonstrating the link just described, we ask how it might have developed. Why do some states have higher levels of racial resentment than others? The death penalty, as many legal scholars have noted, is closely connected to the history of lynching. In fact, one of the major justifications for the expansion of the death penalty in the 1930s was precisely that it would lead to a reduction in the number of lynchings. Lynchings, of course, both reflect and reinforce extreme levels of racial hostility. Therefore, we explore the indirect effects of lynchings on death sentencing as mediated through state-level racial resentment, and we find support for these patterns. In states where lynching was high, some of the observed higher rates of death sentencing can be attributed to the higher rates of racial resentment that were associated with those lynchings, and reinforced by them. This mediation analysis helps us uncover some of the historical linkages between a practice that legal scholars argue was replaced by the death penalty and which underlies an ugly racial legacy that remains strongly connected to the death penalty today. Here, we show a mechanism for this continued impact: public opinion.

Ours is the first study of which we are aware to make a clear connection between state-level racial resentment and the number of death sentences actually handed down in a given state in a given year. Our findings are entirely consistent with previous studies at the individual level, where the linkage between racial resentment and support for the death penalty has consistently been shown to be high. However, we demonstrate something that has not previously been shown: Racial resentment is a direct driver of something much more important than only other attitudes. In fact, it predicts death sentences, particularly those imposed on black offenders.

Previous Studies of Racial Resentment at the Individual Level

Racial resentment is a concept developed by Donald Kinder and David Sears (Reference Kinder and Sears1981) and further developed by Kinder and Lynn Sanders (Reference Kinder and Sanders1996). As noted by Christopher DeSante and Candis Watts Smith (Reference DeSante and Watts Smith2020), Kinder and Sears developed a new interpretation of the “race problem” based on whites’ perception that “blacks violate such traditional American values as individualism and self-reliance, the work ethic, obedience, and discipline” (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981, 416, quoted in DeSante and Smith Reference DeSante and Watts Smith2020). In this “post-civil rights” view, individual choices, not racial discrimination, explain racially disparate outcomes. Of course, only some whites have these attitudes, but those who do also tend to have a variety of other views hostile to the interests of blacks.

As Ashley Jardina explains (2019, 14–15), whites’ attitudes toward blacks have changed in predictable and observable ways over the generations. There is some significant evidence of sympathy for the harms created by de jure and de facto injustices of the Jim Crow era and support for the major civil rights legislation of the 1960s (of course this was not universal). In the wake of numerous uprisings in the 1960s, however, attitudes hardened, and political leaders such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan developed a new “Southern strategy” based on a newer, subtler form of racism, one based on the idea that blacks have had legal barriers to equality removed and so now need to “buckle down and work harder.”

Michael K. Brown (Reference Brown2009) reviews the connection between racial resentment among whites and a range of attitudes with regard both to criminal justice and to the welfare state. He notes that increased white concern that blacks were not supporting the “hard work” ethos of American values led to decreased white support for various social welfare policies as well as increased white support for harsh criminal justice policies including “three strikes” laws, the death penalty, and other punitive measures often extending beyond the criminal justice realm into policies such as drug-testing for those on public assistance and other policies designed to weaken the welfare state. In Brown’s view, racial resentment is a key element in a widening racial divide across a range of policy opinions, particularly those related to punishment and aid to the needy. His focus is on the rising view among many whites in the post-civil rights era that, with legal barriers to success for blacks removed by the reforms of the 1960s, any remaining racial inequalities can be ascribed to “individual choices.” These choices are deciding to stay in school or not, to marry or to have children out of wedlock, to work or be unemployed, and so on (see Brown Reference Brown2009, 667). Brown builds on a large political science literature in exploring the impact of this “personal responsibility” ethos, an important part of the “post-civil rights racial order” that is closely connected to racial resentment. Such an ideology drove much of the political agenda in the 1980s and 1990s, a period when criminal justice policies were at their most punitive and social welfare policies were cut back substantially.

Racial resentment has been measured by survey researchers with this four-part question:

“Do you agree strongly, agree somewhat, neither agree nor disagree, disagree somewhat, or disagree strongly with each of the following statements?

-

(1) Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.

-

(2) Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.

-

(3) Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.

-

(4) It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder, they could be just as well off as whites” (see Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996, 106).Footnote 1

Some have noted that this scale may capture some degree of conservative sentiment against government assistance, not necessarily driven by racial animosity (for examples see Sniderman and Carmines Reference Sniderman and Carmines1997, Sniderman and Piazza Reference Sniderman and Piazza2002, Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005, Sniderman and Tetlock Reference Sniderman and Tetlock1986). Smith, Kreitzer and Suo (Reference Smith, Kreitzer and Suo2020) assess changes in how race and racist attitudes manifest in public opinion surveys over time and note that “Americans who score high on the racial resentment scale tend to explain ongoing racial inequality in terms of individual behavior, whereas those on the scale’s lower end focus on structural inequalities” (528). So, there could be some overlap between resentment and conservatism generally. Lafleur Stephens-Dougan (Reference Stephens-Dougan2020) notes, however, that despite disagreements over what attitudes the scale is capturing, it continues to do a “remarkably good job of distinguishing between white Americans who express hostility toward blacks and those who do not …” (51). In order to be clear about the impact of racial resentment as opposed to general conservative ideology, we incorporate both measures in our analyses below.

Consistent with our reasoning that racial resentment will motivate increased use of the death penalty, individual-level research reveals strong effects of racial attitudes on support for criminal justice policies. Unnever and Cullen (Reference Unnever and Cullen2007) explore black and white attitudes toward the death penalty as well as a separate measure of white anti-black racism. When they statistically control for racism, they find that non-racist whites have about the same level of support for the death penalty as do blacks. But in 2002, research showed that black and white support for the death penalty differed by 29 percentage points: 44 percent of blacks supported it, compared to 73 percent of whites (Unnever and Cullen Reference Unnever and Cullen2007, 1281; see also Unnever and Cullen Reference Unnever and Cullen2010 and 2011).

Peffley and Hurwitz (Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2007, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010) provide extensive evidence of the linkage between racial attitudes and support for punitive criminal justice policies, including specifically the death penalty. In fact, in a survey experiment where they primed respondents with the statement that “some people say that the death penalty is unfair because most of the people who are executed are African Americans,” the percentage of whites who supported the punishment increased by 12 percentage points over the baseline. For blacks, it decreased by the same amount. When primed with the statement that “some people say the death penalty is unfair because too many innocent people are being executed,” there was no change among whites (-0.68 percent from the baseline) and a -16 percent drop for black respondents (2007, 1002). There is strong reason, in other words, to believe that racial resentment is strongly connected to death penalty attitudes at the individual level.

DeSante and Smith (Reference DeSante and Watts Smith2020) show that levels of racial resentment have stayed steady or grown more hostile to blacks over time, though they indicate that younger (or Millennial) white Americans report more progressive views on the scale than their elders. In any case, racial resentment is a distinct psychological construct from support for the death penalty or general ideological left-right position, and, despite its limitations, continues to predict attitudes on a variety of criminal justice issues (Enns and Ramirez Reference Enns and Ramirez2018; Kam and Burge Reference Kam and Burge2019).

Smith, Kreitzer, and Suo (Reference Smith, Kreitzer and Suo2020) developed the dynamic state-level estimates of racial resentment on which we rely here. In discussing the value of their new measurement tool, they note their hope that it will lead to new research questions, including: “What is the link between racial attitudes and change in policies over time?” (535). This is precisely our goal.

Racial Hostility, Lynchings, and the Death Penalty in Historical Context

Historians and legal scholars have long noted the connection between racial hostility and the death penalty, particularly the connection between lynching and capital punishment. A recent report from the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC, 2020) notes the substitution of the death penalty for lynchings in the early 20th century (5-16), a key phenomenon in our analysis. Carol and Jordan Steiker (2010) describe the idea that the death penalty was needed as an antidote to lynching as one of the most powerful, but now forgotten, arguments for the retention of capital punishment around the turn of the 20th century. James Clarke (Reference Clarke1998) documents the decline in southern lynchings in the early decades of the 20th century. By the 1920s, he writes:

… perhaps the most important reason that lynching declined is that it was replaced by a more palatable form of violence. For the first time, court-ordered executions supplanted lynching in the former slave states…. There was no longer any need for lynching, Southern leaders insisted; almost the same degree of control and intimidation could still be exerted over blacks with capital punishment (Clarke Reference Clarke1998, 284–285).

The Equal Justice Initiative corroborates this analysis: “As early as the 1920s, lynchings were disfavored because of the ‘bad press’ they garnered. Southern legislatures shifted to capital punishment so that legal and ostensibly unbiased court proceedings could serve the same purpose” (EJI 2017, 62; see also Whitaker Reference Whitaker2008). “The decline of lynching … relied heavily on the increased use of capital punishment imposed by court order following an often accelerated trial. That the death penalty’s roots are sunk deep in the legacy of lynching is evidenced by the fact that public executions to mollify the mob continued after the practice was legally banned” (EJI 2017, 5).

Lynchings were frightful demonstrations of whites’ willingness to use violence to enforce white dominance (Tolnay and Beck Reference Tolnay and Beck1995). Therefore, we may expect places with a history of lynchings to have higher levels of racial resentment (Zimring Reference Zimring2003; Messner, Baumer, and Rosenfeld Reference Messner, Baumer and Rosenfeld2006; Jacobs, Carmichael, and Kent Reference Jacobs, Carmichael and Kent2005; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner Frank, Box-Steffensmeier, Campbell, Caron and Sherman2020). A key element in our theory, however, is that lynchings and white racial hostility are mutually constitutive: Lynchings stem from hostility, but they also accentuate and perpetuate it, leaving a legacy of hostility even when lynchings no longer occur.

A Theory of Racial Hostility and the Death Penalty at the State Level

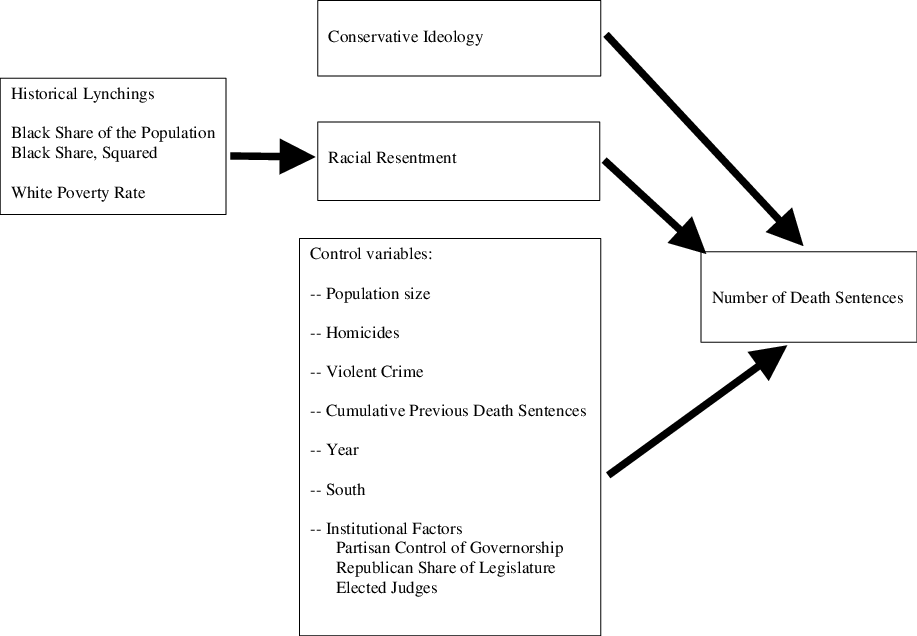

We posit that a state’s use of the death penalty is driven by racial hostility. We understand that this hostility may be related to a state’s own history, particularly with lynching, but that lynching itself may be both a sign of previous levels of racial hostility as well as a predictor of future levels of the same concept. We follow Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen (Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018) in positing the possible influence of deep historical roots of public policy. Their focus was slavery, and they demonstrated powerful legacy effects enduring to modern times. Of course, their argument was not that the share of the population enslaved in 1860 directly causes any outcome variable today. Rather, they noted that factors leading to greater historical use of slavery might endure and have other consequences and that slavery itself could also affect the historical trajectories of local communities in subsequent periods of history. Racial attitudes that historically led to discrimination and racial subjugation reproduce themselves within the white population through the institutions and political cultures of a given area. We make a similar argument here with lynching and the death penalty. Figure 1 lays out our theory in graphical form.

Figure 1. A Model of Death Sentencing at the State Level.

Our main argument is that present-day levels of racial resentment drive use of the death penalty. As described in the data section below and illustrated in the Figure, we propose control variables for ideology, crime-related factors, and a series of institutional factors.

The left-most set of variables in Figure 1 shows a series of indirect effects, mediated through racial resentment: Lynchings, black population share (and its squared term), and white poverty. Blalock (Reference Blalock1967) argues that resource competition and status anxiety are causes of white hostility, as disadvantaged white populations are more likely to blame racial minorities for their own economic precarity, particularly as the black share of the population is greater. Several prior studies have evaluated the impact of economic disadvantage among white populations, finding linkages between discriminatory legal practices and interracial economic competition (King, Messner, and Baller Reference King, Messner and Baller2009; Wang and Mears Reference Wang and Mears2010). Duxbury (Reference Duxbury2021) argues that racial demographics are associated with white fear of crime and /or hostility toward blacks. In his analysis of state adoption of tough-on-crime laws, he writes:

[A]s the size of the minority group increases, majority racial groups must mobilize to a greater degree in support of new social policies that restrict the minority group’s competitive power. Thus, rather than influencing how criminal justice actors enforce existing criminal laws, minority group size may elicit large-scale shifts in dominant groups’ policy interests that shape how new criminal law is constructed and the rate at which new criminal laws are adopted (Duxbury Reference Duxbury2021, 126–127).

Threat theory predicts that threat to the white population’s economic and political standing motivates them to support social policies that repress the ability of the black population to compete for economic and political resources (Duxbury Reference Duxbury2021, 129).

Duxbury notes that Blalock used slavery and Jim Crow laws as legal systems that achieved the goal of maintaining majority group dominance, noting that many see the harsh-on-crime laws that he analyzes as modern forms of slavery or Jim Crow (e.g., Alexander Reference Alexander2010; Wacquant Reference Wacquant2000). We can add the death penalty to this list. And we can be more straightforward in our language: policies that “repress the ability of the black population to compete for economic and political resources” can be called policies based on white racial hostility. In short, our main concern is whether, net of reasonable controls, we see a residual effect for racial resentment and whether we see more powerful effects for this factor in predicting death sentences with black offenders than predicting those with white offenders. We refer to this as “racial hostility” rather than “racial threat” because we see no threat coming from the black population, but considerable hostility moving in the other direction.

The remainder of Figure 1 clarifies the direct effects that we expect to see on states’ use of the death penalty: conservative ideology, racial resentment, and controls. Conservative ideology is a key variable in the model as it allows us to distinguish two conceptually distinct possible sources of support for the death penalty.

Data and Methods

Our analytic approach is to estimate a cross-sectional time-series model where the units are the US states and time is measured in years. Our dependent variable is the number of death sentences imposed in a given state in a given year, measured separately for black and white defendants. We include only those states having a legally valid death penalty statute in place in the year of analysis. Table 1 lays out the variables included in our model and provides descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics.

Note: Lynchings refers to the total number from 1883 to 1941 and are fixed at the same value for all years, by state. All the other variables are annual from 1989 through 2019 and vary by state as well as by year.

Because of concern discussed in our review of the literature that racial resentment may not be a clean measure separate from general conservative ideology, we control for that directly. Because death sentences are clearly related to crime, particularly homicides, we control for these factors; population size and previous death sentences are important controls as well (see Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner Frank, Box-Steffensmeier, Campbell, Caron and Sherman2020 who show that sentencing at the local level is highly inertial, with some jurisdictions developing strong habits over time, and others not doing so; positive coefficients for this variable document this inertial effect). Institutional factors such as partisan control of the legislature and executive branch and the method of selecting judges are important controls (see Brace and Boyea Reference Brace and Boyea2008; Canes-Wrone et al. Reference Canes-Wrone, Clark and Kelly2014), as is being a Southern state. We distinguish states that select trial judges by appointment from those that rely on elections with a dummy variable.Footnote 2 The data come from the following sources:

Death sentences: The number of black and white death sentences are the dependent variables in our analysis. We model each variable separately to disentangle the distinct effects of racial resentment on each outcome. Data come from Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner Frank, Box-Steffensmeier, Campbell, Caron and Sherman2020).

Racial resentment: State-level racial resentment measures come from Smith, Kreitzer, and Suo (Reference Smith, Kreitzer and Suo2020). Note that this is measured using ANES data from 1988, 1990, 1992, 1994, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, and 2016. We use linear interpolation to impute estimates of resentment for those years without a contemporaneous measurement.

Conservative ideology: We use Berry et al.’s (Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and Hanson1998) measure of state level ideology, updated through 2016 by Fording (Reference Fording2018).Footnote 3 The measure obtains higher values when elected officials and members of the public exhibit more conservative policy preferences.

Lynchings: Our measure of lynching comes from Tolnay and Beck’s (Reference Tolnay and Beck1995) data on historical lynchings, recently updated by Seguin and Rigby (Reference Seguin and Rigby2019). The measure is the total number of lynchings that occurred within a state between 1883 and 1941.

Demographics: We include several demographic variables using data from the U.S. Census. We control for the percent black population to account for hypothesized relationships between black population size and white hostility. Consistent with Blalock’s (Reference Blalock1967) reasoning, we specify a quadratic term for the percent black population as well as a linear term to account for nonlinear relationships. We also include the white poverty rate to capture any effects of white status anxieties on racial resentments. Further, we control for population size to account for variable exposure: highly populated states are likely to have more death sentences.

Crime: To capture death-eligible crimes, we control for the number of homicides in a state. Although all homicides are not eligible for punishment by death, a measure of death-eligible homicides is not available. However, it is reasonable to use homicides as a proxy for the following reasons. Within any state, the share of all homicides that are eligible for capital punishment is determined by law, and, in the aggregate, can be expected to be relatively constant over time. Some states have very expansive death-eligibility laws (for example any homicide committed during a felony), and others have very restrictive ones (for example, only killings of active-duty law enforcement or by individuals already incarcerated serving a life sentence). Within any state, only a certain percentage of all homicides are death eligible, and this can vary substantially across the states. For any given state, however, it is a relatively constant share over time. Therefore, annual counts of homicides can be used as a proxy for annual counts of death-eligible ones in a model that also controls for state, as does ours. To further capture how crime may impact death sentencing, we also include the violent crime rate. This allows us to hold constant a range of serious offenses in our models for death sentencing. The measures come from the FBI Supplementary Homicide Reports and Uniform Crime Reports (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2021).

Institutional factors: We control for several institutional and political factors using data from the National Conference of state legislatures. First, we account for Republican party influence by including the Republican share of the state legislature and a binary variable for whether the governor is Republican. Second, we include a binary variable that captures whether the state has elected trial court judges, as some studies suggest that elected trial judges tend to be more punitive (e.g., Huber and Gordon Reference Huber and Gordon2004).

We lag all independent variables by one year to ensure the correct temporal order of the estimated relationships. (Note that the variable for historical lynchings does not vary over time.) As we lag our independent variables by one year, we predict death sentences in the period of 1989 through 2017. This provides 1,106 state-years for our analysis.

Analytic Strategy

We fit a negative binomial regression to account for over-dispersion in the number of death sentences each year. Since state death sentences are influenced by population density, we include the natural logarithm of the state population as an offset parameter (Osgood Reference Osgood2002). This specification alters the interpretation of negative binomial coefficients to one of the annual number of death sentences per capita. Death sentences may also be influenced by unobserved state-level heterogeneity. We address this by including a state-level frailty term in all models. (This also addresses the issue that states differ in the shares of all homicides that are eligible for capital punishment.) Hence, the models are estimated as multilevel negative binomial models with state-years nested in states.Footnote 4 Our mediation analyses use the methods developed by Imai, Keele, and Tingley (Reference Imai, Keele and Kingley2010) and later extended to negative binomial models by Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Cheng, Zijian Guo, Ismail and Gansky2018) formally to test for indirect effects. We estimate separate mediation models for each pathway of interest and present the results for each indirect pathway below.

Results

Table 2 presents results from negative binomial mixed models predicting the death sentencing rate per capita for black (Models 1–3) and white (Models 4–6) offenders. As we have two opinion variables and want to assess the marginal value of the resentment measure after controlling for ideology, we present models with each opinion measure separately, then combined. Models 3 and 6 present the fully specified results.

Table 2. Predicting State Level Death Sentencing, for Black and White Offenders.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<.001 (Two-tailed test). Intercept not shown. N = 1,016. Coefficients are Incident Rate Ratios from negative binomial mixed models with standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the number of death sentences in a given year in a given state.

Consistent with expectations, Models 1 through 3 reveal that the incidence rate of black death sentencing is particularly sensitive to variation in racial resentment and conservative ideology. Each one percent increase in the racial resentment measure is associated with an 8.1 percent increase in the incidence rate of black death sentences per capita. Conservative ideology is also positively associated with black death sentencing, but the relationship is weaker. Each one percent increase in conservative ideology corresponds with a 1.3 percent increase in the incidence rate of black death sentences per capita. Further, AIC and BIC are lower in the model that excludes conservative ideology and retains racial resentment (Model 1) than the model that excludes racial resentment and retains conservative ideology (Model 2), and lower still when both are included (Model 3). Consistent with expectations, this result reveals racial resentment is a stronger predictor of black death sentencing rates than conservative ideology. Model 3 shows that the coefficients for both opinion measures are robust when included in the same model, indicating that resentment acts as a separate construct from general ideological conservatism. Documenting that resentment has such a powerful impact, over and above the additional impact of conservative ideology in a model with a full set of controls is our main point.

Turning to the control variables, the percent black population, total number of lynchings, and white poverty rate are all nonsignificant. Because we posit that these will have an indirect effect, not a direct one, we explore these indirect effects in a mediation model below. Also of note is that the violent crime rate is positively associated with black death sentences, indicating that a greater number of black offenders are sentenced to death when violent crime increases. This result is consistent with a body of research describing how black populations and offenders are disproportionately punished when violent crime increases (e.g., Yates and Fording Reference Yates and Fording2005). Note, however, that homicides are nonsignificant across all six models presented. As homicides are a legal prerequisite for death sentences, this is surprising to say the least. However, it may well be that the public, and public officials, respond more to violent crime in general than to homicides in particular (and of course the two variables are correlated). Among control variables, there are significant effects for year and for cumulative previous death sentences, but the other variables are nonsignificant.

In Models 4 to 6, we replicate model specifications but treat white death sentences as the dependent variable. Interestingly, racial resentment and conservative ideologies are both positive predictors of the white death sentence rate per capita. And, including racial resentment improves model fit as compared to the model that only includes conservative ideology (Model 5). These results likely reflect “spillover” effects of death sentencing on white offenders, where racial resentment is associated with greater use of the death penalty, with implications for both black and white offenders (e.g., Garland Reference Garland2010). In contrast to the black death sentence rate, white death sentences do not appear to be associated with violent crime rates and are more common in states that elect trial judges. The other control variables have similar effects in the two sets of models.

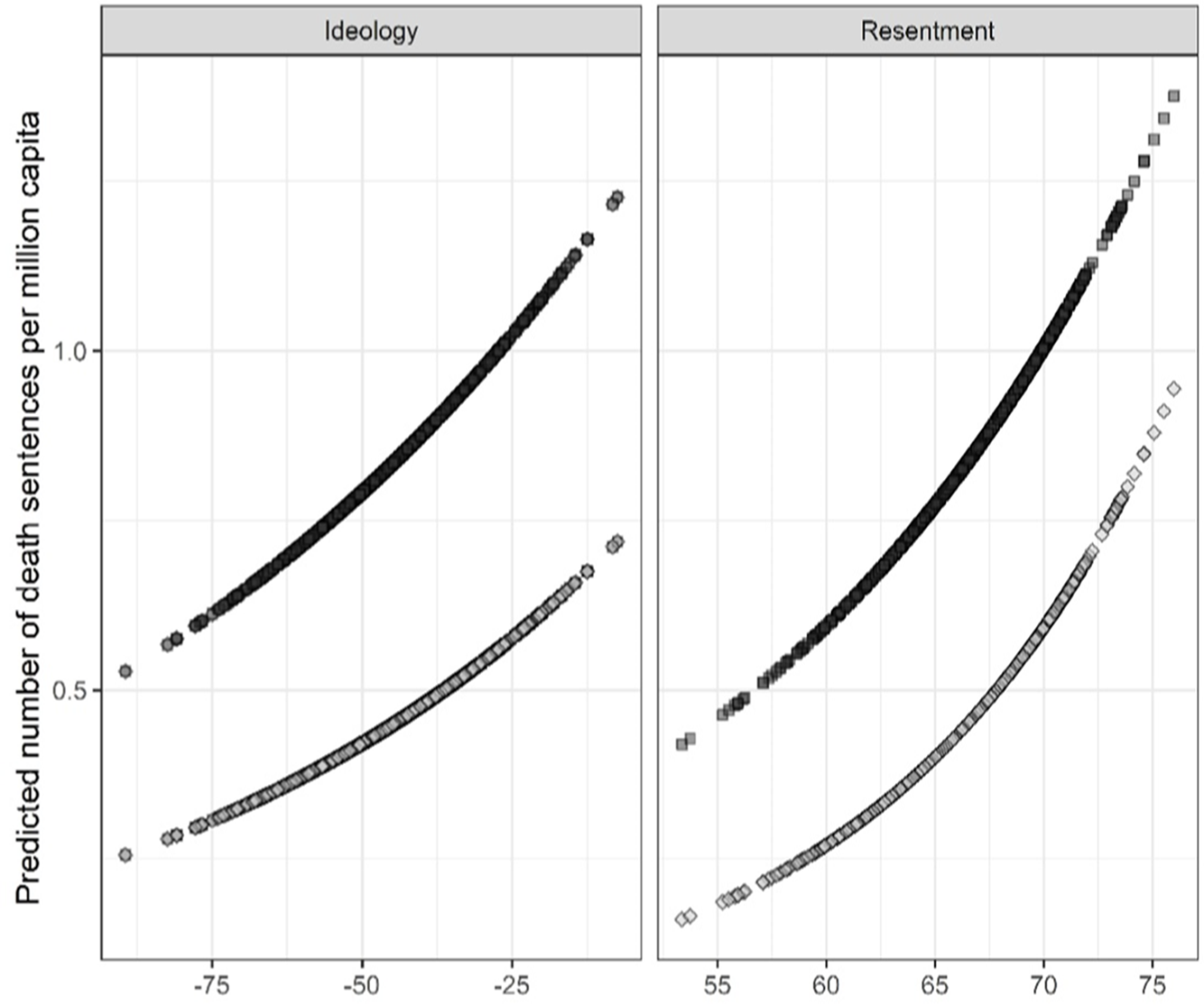

Figure 2 presents predicted probabilities from Models 3 and 6 across different levels of conservative ideology and racial resentment. In each panel of the figure, both black and white death sentences are shown.

Figure 2. Predicted Death Sentencing Rates for Black and White Offenders, by Levels of Conservative Ideology and Racial Resentment.

Note: Solid symbols refer to black offenders; hollow ones refer to white offenders. Results from models 3 and 6 in Table 2.

Figure 2 makes clear that blacks are much more likely to be sentenced to death than whites no matter the level of resentment or ideology. In both panels, the values for black offenders are consistently and substantially higher than the values for whites. Moving from the low to the highest values on resentment leads to more than triple the predicted number of death sentences for both racial groups. Moving from low to high on conservative ideology leads to more than double the rate of death sentencing for blacks, but less so for whites.

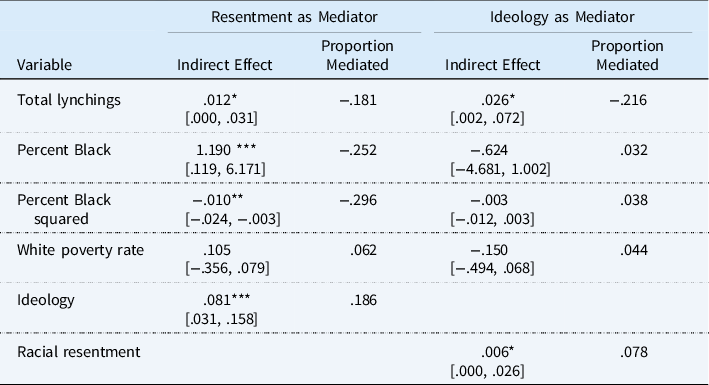

Primary results from our negative binomial models support our hypotheses regarding how racial resentment translates into death sentencing, with pronounced effects for black offenders. However, we did not find positive effects for percent black population, history of lynchings, or the white poverty rate. We now turn to mediation analyses to formally test indirect effects from each of these variables. Table 3 presents results from mediation analyses predicting black death sentencing rates. Because of our central interest in indirect pathways, we report indirect effects (average causal mediated effects, ACME) from each mediator model in Table 3. Full results from all mediation analyses are reported in our Appendix.

Table 3. Mediation Analysis of Indirect Effects on Black Death Sentences per Capita.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Two-tailed test). p-values calculated using 10,000 Monte Carlo samples (Imai et al. Reference Imai, Keele and Kingley2010). Confidence intervals in brackets. Standard errors clustered on states. All indirect effects multiplied by 1,000,000 to be interpreted as effects per million capita. N = 1,016.

Consistent with expectations, there is a positive indirect effect from histories of lynchings acting through racial resentment, where each one-unit increase in historical lynchings is associated with a 1 percent (exp(.009)=1.009) indirect increase in the rate of black death sentencing because of increases in racial resentment.Footnote 5 Also consistent with expectations, there is a nonlinear indirect effect from the size of the black population. This result indicates that increases in the size of the black population are indirectly associated with black death sentences due to increases in racial resentment, but there is a threshold to this effect. Similarly, conservative ideology is, in part, indirectly associated, where racial resentment explains roughly 22 percent of the direct effect of conservative ideology on black death sentences. These results are consistent with expectations that histories of racial conflict and conservative ideology indirectly contribute to black death sentences via their effect on racial resentment. However, we do not find an indirect effect from the white poverty rate.

Turning to indirect effects that treat conservative ideology as the mediator, the size of the black population does not have a significant indirect effect acting through conservative ideology, and nor does the white poverty rate. The total number of historical lynchings is associated with indirect increases in the number of black death sentences per capita due to increases in conservative ideology. Similarly, although there is an indirect effect of racial resentment on black death sentences acting through conservative ideology, it is much weaker than the indirect effect of conservative ideology acting through racial resentment. Conservative ideology explains 6.5% of the effect of racial resentment on black death sentences, while racial resentment explains 22% of the effect of conservative ideology. Consistent with expectations, these results suggest that most of the effect of racial conflict and conservative ideology can be explained by their indirect effects on racial resentment.

Table 4 replicates these analyses treating white death sentences as the dependent variable.

Table 4. Mediation Analysis of Indirect Effects on White Death Sentences per Capita.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 (Two-tailed test). p-values calculated using 10,000 Monte Carlo samples (Imai et al. Reference Imai, Keele and Kingley2010). Confidence intervals in brackets. Standard errors clustered on states. All indirect effects multiplied by 1,000,000 to be interpreted as effects per million capita. N = 1,016.

Consistent with primary models, the direction and significance of each indirect effect aligns with the indirect effects for death sentences with black offenders. Lynchings, the size of the black population, and conservative ideology all have positive indirect effects acting through racial resentment, while lynchings and racial resentment have smaller indirect effects acting through conservative ideology. These results reveal that histories of racial conflict and contemporary demographics have collateral consequences for white offenders by contributing to death sentence usage. The strongest effects, however, are targeted on black offenders.

In sum, results provide support for our expectation that racial resentment will motivate usage of the death penalty and that histories of racial conflict carry indirect consequences for death sentences by increasing racial resentment. We also found support for expectations that these effects would be concentrated on black offenders more than white offenders. Racial resentment has spillover consequences for white offenders, but the effects of racial resentment are strongest for black death sentences. For white offenders, but not for blacks, elected judges matter, but violence does not. This may suggest that the use of the death penalty against white offenders is a residual spill-over from its use against black offenders.

Our expectations about an indirect effect of history, mediated through aggregate levels of racial resentment, were fully borne out by the results. The death penalty is significantly driven by racial resentment, and racial resentment reflects historical and demographic factors related to lynchings and white racial hostility.

Conclusion

The modern death penalty is supposed to be reserved for the most heinous crimes and those who are the most deserving. The vast and complicated jurisprudence that has accumulated since Gregg mandates proportionality review, bars any death sentence where the culpability of the offender is not explicitly weighed against any possible mitigating factors, and is subject to extraordinary procedural safeguards (see Zimring Reference Zimring2003). And yet, despite all these reforms mandated by the justices’ rejection of the system they critiqued in Furman, the “new and improved” death penalty we analyze here appears to have the same flaws that Justice Stewart and others identified back in 1972. In fact, while the Justices suspected race but did not find it, and found capriciousness, we can verify both. The death penalty is imposed freakishly; in particular, once we control for population size, homicides have no effect (though violent crime does). For white offenders, even violence has no predictive value, but judicial selection procedures do. A heavy element of inertia affects the process, so that a strong predictor of death sentencing is simply previous death sentencing. But if any logic can be discerned, it is related to race, the legacy of lynchings, and public passions.

Public attitudes and opinions can affect the death penalty through many pathways. Eberhardt and colleagues (Reference Eberhardt, Davies, Valerie and Johnson2006) analyzed court records of death sentencing decisions in Philadelphia, focusing on jury decision-making in the penalty phase of capital trials. In the 44 cases with black offenders and white victims, they found that defendants with more “stereotypically Black” physical characteristics were sentenced to death at a higher rate; 57.5 percent of those with higher values on the index received a death sentence, compared to 24.4 percent of those with low values (2006, 384). (Note that Eberhardt and colleagues were studying actual judicial records; they had their coders evaluate photos of the defendants after the fact.) Eberhardt and colleagues’ troubling findings suggest a greater willingness of jury members to dehumanize or to “other” a defendant in cases with stereotypically black appearance. Public opinion, then, can affect jury decisions. Eberhardt and colleagues’ analysis suggests that this can be an ugly process marred by significant bias.

We have shown here a different impact of public opinion, but one with similar distasteful features. By aggregating public opinion to the state-year level, we build on micro-level analyses that have amply demonstrated that racial resentment is strongly correlated to support for capital punishment. We show that aggregate levels of racial resentment strongly predict state death sentencing behaviors. These effects are much more powerful and consistent with regard to black offenders than white offenders, consistent with our theory. And, while we found a strong direct effect for racial resentment even while controlling for general conservative ideology and other reasonable controls, we also found that racial resentment itself is driven by deep-seated historical roots, including lynching. Those historical roots, then, continue to affect current day usage of the death penalty because of their continuing effects on public opinion.

Our results carry implications for prior research tracing use of the death penalty to legacies of vigilantism. Zimring (Reference Zimring2003) reasons that capital punishment is used most frequently in jurisdictions that have strong traditions of vigilantism. Prior research evaluating this hypothesis, however, has typically measured vigilantism using the number of historical lynchings, which conflates racial antipathy with reliance on vigilante justice. Our results suggest that the historical legacies of lynchings carry indirect effects for death sentencing through both pathways. On the one hand, lynchings indirectly increase death sentences as a function of contemporary racial resentment, consistent with a racial antipathy interpretation. On the other hand, there is also an indirect effect of historical lynchings through contemporary conservative ideologies reflective of antigovernment intervention, consistent with the vigilantism hypothesis.

We would not argue that public opinion should be unrelated to a state’s use of the death penalty. Indeed, responsiveness to public opinion is a fundamental goal of representative democracy. In this article, however, we have distinguished between mere political conservatism and a more sinister element: White resentment and hostility toward blacks. When we consider the micro-level evidence from previous studies showing a strong linkage between racial hostility and support for the death penalty, the accumulated legal literature showing disproportionate use of the death penalty against black offenders with white victims, and the evidence presented here showing a lack of correspondence between homicides and death sentences but a strong role for racial resentment, it is hard to conclude that the death penalty can withstand constitutional or moral scrutiny.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2022.30