A number of recent policy initiatives in the health service converge on the issue of personal development plans (PDPs) and make it essential that all psychiatrists have a system for generating PDPs that is robust and accountable as well as effective and efficient. Such policy initiatives include:

-

• A First Class Service (Department of Health, 1998), which laid down a requirement for all National Health Service (NHS) staff to have a PDP in place by April 2000;

-

• clinical governance, with a central expectation of an adequately trained workforce participating in CPD to allow changing service demands to be met;

-

• General Medical Council (GMC)/ Department of Health proposals for appraisal and revalidation, which include an explicit requirement for practitioners to maintain a portfolio of evidence regarding their practice, which will include some form of PDP;

-

• the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ policy on CPD, adopted in April 2001 (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001), makes PDPs (agreed in peer groups) the central focus of CPD, thus obviating the need for validating events and counting credits for approved training (Reference Katona and JacksonKatona & Jackson, 2000).

Increasingly, it is recognised that CPD should be planned and proactive rather than the purely reactive process it has often been in the past. PDPs provide a means of planning CPD. An earlier paper in APT (Reference HollowayHolloway, 2000) gave a comprehensive overview of PDPs in the context of CPD and revalidation. Here, I update that review and focus on practical means of implementing PDPs in the setting of peer groups.

The context of appraisal and revalidation

Current proposals agreed by the GMC, the British Medical Association (BMA) and the Department of Health state that revalidation will primarily (and for the majority of practitioners, entirely) rest on the doctor having had satisfactory appraisals for 5 years in succession. Abbreviated paperwork from the annual appraisals will be collected together and submitted to a revalidation group at the GMC and, if deemed satisfactory, revalidation will follow automatically. The GMC is reserving the option of conducting a random audit of the appraisal processes, which may entail detailed examination of the original appraisal paperwork as well as using other checks such as ‘360-degree’ appraisal instruments. This form of appraisal has become a common tool in the business world and entails seeking views on an individual's performance from all those working with him or her, whether subordinates or peers, or acting in a line management capacity to the appraisee. The appraisee, in turn, would be involved in offering views on those by whom he or she has been rated – hence 360 degrees. The GMC is exploring methods modelled on the physician associate ratings successfully validated by Ramsey and colleagues for doctors practising in North America (Reference RamseyRamsey, 1993). It will be essential that appraisal processes are robust and accountable and it has been pointed out that appraisers will carry a significant professional responsibility for the quality of their work in this regard.

It has also been pointed out that linking appraisal with revalidation turns it from an entirely confidential, developmental and facilitative exercise (as an educationalist would define it) into one which has a crucial regulatory function. The challenge for those introducing appraisal and for appraisees themselves will be to retain the constructive ethos underlying appraisal and ensure that it is experienced as a supportive process for those undergoing it. However that challenge is addressed, it is clear that PDPs will be a central element of appraisal processes and will be the mechanism by which practitioners identify the training plans that will enable them both to keep up to date and also, importantly, to develop new skills in order to meet the changing requirements of their patients and the organisations within which they work.

David Graham, Postgraduate Dean for Merseyside, was appointed Chairman of the Appraisal Implementation Steering Group in March 2002 and he has commented on the importance of appraisal and how it is likely to be implemented (Reference GrahamGraham, 2002). Reference PeytonPeyton (2000) provides a practical manual supporting the introduction of appraisal procedures, and further useful information on the implementation of appraisal and revalidation is available on the website co-hosted by the GMC and Department of Health at http://www.revalidationuk.info.

The theory of PDPs

A First Class Service (Department of Health, 1998: p. 42) defines CPD as ‘a process of lifelong learning for all individuals and teams, which meets the needs of patients and delivers the health outcomes and healthcare priorities of the NHS, and which enables professionals to expand and fulfil their potential’.

This shows that the Government's intention is for the needs of the organisation to sit firmly and squarely in the process of lifelong learning for doctors. Reference Katona and JacksonKatona & Jackson (2000) and the College Council Report Good Psychiatric Practice: CPD (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001) describe how the College has elected to make PDPs the cornerstone of CDP, with those generated by peer groups becoming the arbiter of our educational needs and the sole evidence required to demonstrate participation in CPD for those registered with the programme operated by the College.

Personal development plans are designed to make CPD a proactive process contrasting with the reactive manner in which training has been undertaken by many of us in the past (e.g. going to conferences we just happen to hear about or that cover an area we happen to be interested in). The process is very similar to that of setting educational objectives for our trainees to ensure that they get the most out of training attachments, addressing gaps in skills, knowledge or attitudes as well as building on existing strengths. In this way, PDPs can help psychiatrists to remedy deficits, ensure maintenance of existing attributes and develop new ones where they wish or where the needs of the service dictate.

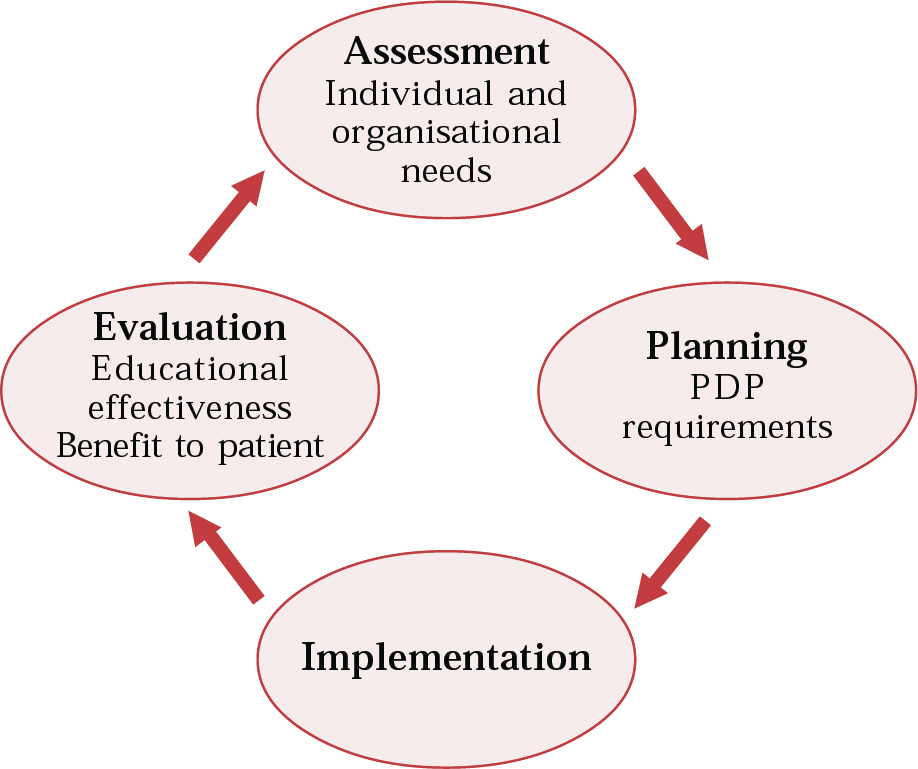

To be entirely successful, some form of feedback process is required and this is referred to in A First Class Service (Department of Health, 1998) as the ‘CPD cycle’ (Fig. 1). The resemblance of this to an audit cycle will be apparent immediately. Development needs are assessed; means of achieving them are planned and put into practice. As with audit, the effectiveness of CPD and PDPs will ultimately depend on ‘closing the loop’ and ensuring that action is taken if the crucial stage of evaluation suggests failure or only partial achievement of some learning/educational objective.

The College considered three main options for generating PDPs: ‘buddy’ systems (mutually agreed pairings of practitioners, usually of equivalent standing), mentors (similar to the above, but usually implying a hierarchical relationship or, at least, differential seniority), or peer groups. The latter have become the chosen vehicle for delivering PDPs. A survey of psychiatrists in one trust suggested that the majority considered this an acceptable mechanism for developing PDPs (Reference NewbyNewby, 1999). Although College policy does not specifically prohibit other mechanisms, it is clearly based on an assumption that peer groups will be the norm for PDP generation.

However, it is conceivable that some colleagues may have a personal objection to working in peer groups to develop their PDP, or there may be specific situations where this becomes difficult. For example in minority specialities such as neuropsychiatry, practitioners might have to go a long way to find someone working in their field. There is nothing in College policy to say that peer groups must be formed in accordance with sub-speciality boundaries, although some colleagues choose to establish groups in this way. Although there is nothing, in principle, to stop the formation of peer groups across trust boundaries, geographical constraints may still pose difficulties. Equally, in the case of doctors who are specifically identified as underperforming, peer groups may not be considered an ideal setting for addressing all of their needs. How such issues will be resolved remains unclear although the light of experience will no doubt influence solutions.

As peer group PDPs will be the norm for the vast majority, an immediate challenge will be to reconcile the need for an individual PDP agreed in the appraisal process (one-to-one with the appraiser) and for one agreed in the peer group to satisfy CPD registration requirements. It would seem absurd to contemplate having two separate and distinct PDPs. If it is accepted that there should be only one, some agreement will have to be reached on how discussions on PDP requirements in the two settings should influence one another. It can be envisaged that there will be a two-way interaction, with appraisal interviews identifying development objectives, which are worked up and refined in the peer group review (and vice versa). Once again, the ground rules for this have yet to be established but having some explicit linkage between the processes would seem to be essential.

Making PDPs work

Following the publication of the College's policy document on CPD (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001), a series of workshops was arranged for psychiatrists working in the Leeds Community and Mental Health (Teaching) NHS Trust. Their purpose was to disseminate information and to pilot the Trust's processes and paperwork for setting up PDP peer groups. Much of the advice in this section comes from experience gained in those workshops as well as from discussion with colleagues who are introducing PDPs, especially in meetings organised by the College's CPD Committee. A full report and evaluation of the Leeds system is available on request by e-mail from Mary.Bove@lcmhst-tr.northy.nhs.uk.

Colleagues are welcome to plagiarise or adapt any aspect of the paperwork if they wish to introduce it into their local systems.

Establishment of peer groups

Initially, two meetings were advertised with the intention of setting the ball rolling, and these were attended by some 80 practitioners (63% of the workforce). The workshop organisers generated groupings of between 3 and 10 doctors according to seniority (non-consultant, non-training grade doctors such as staff grades were offered a group of their own) or care group (general adult psychiatry, old age psychiatry, etc.). At the workshops, delegates were given the option of swapping or reconfiguring groups although, in practice, the number who did so was surprisingly small.

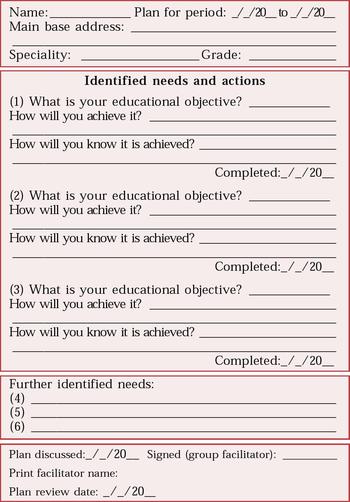

Some initial training and orientation were offered, setting out the context of PDPs much as discussed earlier, but the majority of the time was spent allowing delegates to draw up their first PDP. A template (Fig. 2) was provided on which the PDP could be recorded, along with explanatory notes (Box 1) and the College's suggestions for a checklist for PDP (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001: pp. 25–26). The aim was for all delegates to complete their first PDP before the end of the session. This was achieved, with feedback indicating that a clear majority found the paperwork and process easy to use and the time spent of real value in considering personal development needs.

Box 1 Notes for completion of PDP (from Leeds documentation, with permission)

-

• In your chosen review group, you should spend some time considering your current working situation and any related development needs of which you have become aware.

-

• As a prompt for this, you may wish to refer to the headings from the College's checklist.

-

• Objectives should as far as possible obey SMART criteria – i.e. they should be: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-limited.

-

• You should select three priority objectives and, through discussion, agree a plan for addressing each objective and assessing your success with it. In the space marked ‘How will you know it is achieved?’ you should indicate some benchmark by which you can gauge achievement of the objective (specificity of this marker is particularly important).

-

• There is a space to record three additional objectives. These may be carried over to a subsequent review date or you may choose to undertake some action on them immediately.

-

• Either way, the first task at subsequent reviews should be to check progress with objectives, filling in the completion date only when you are satisfied with achievement. If necessary, previous objectives may be carried over onto subsequent forms.

-

• Having set objectives, you should ensure that a review date is set and you agree the person with whom the review will be undertaken.

It was anticipated that peer groups set up by this process would organise further meetings themselves exclusively for group members and ensure that a rolling programme of PDP reviews was established. In fact, a large proportion of participants requested that further set meetings be established to remove the administrative disincentives of having to organise such events. Although this tends to reduce the consistency of membership of the groups (unless members make it their business to ensure that they all sign up for the same meetings) experience at the three subsequent meetings set up in this way suggests that it remains a valid and valued means of continuing peer groups. The intention in Leeds, therefore, is to offer the choice.

Mechanics of each peer group meeting

The first task at each meeting is to allow time to review existing PDPs with the principle of the CPD cycle in mind. Have existing objectives been achieved? If not, do they remain a priority? If so, what has prevented the objective being attained? How can this be remedied?

In principle, there is nothing to stop the group agreeing that a completely new plan needs to be or should be developed, especially if the practitioner's circumstances have changed. For instance, for someone who has changed jobs, a previous objective may no longer apply and new priorities may press. Someone moving into medical management may have greater need to develop new management skills rather than, say, the cognitive–behavioural therapy skills required in their previous job. Care should be taken, however, to ensure that any unfulfilled objectives that remain pertinent are carried over in some format to subsequent PDPs. The group itself should be used as a reference point to determine whether this is necessary.

Having reviewed existing plans, the group should ensure that new plans are drawn up where necessary, taking into account input from one-to-one appraisal sessions (see above) and the practitioner's current working situation and ensuring consideration of all the domains of practice, as in the College's checklist. Another way of breaking this task down is to consider the headings in the GMC's core document, Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 2001) (Box 2).

Box 2 Section headings from Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 2001)

Good clinical care

Maintaining good medical practice

Teaching and training, appraisal and assessing

Relationships with patients

Working with colleagues

Probity

Health

An important and potentially very rewarding element of peer group functioning is its capacity to serve as a think tank for the creation of novel means of achieving educational ends. Developing a necessary skill might not have to rely on finding the right course. Groups may be able to suggest, for example, clinical attachments that would fulfil the same purpose. In some cases, the group itself might be able to assemble for a peer-based learning experience or commission special teaching for shared educational needs that might be difficult to fulfil elsewhere.

To this end, it can be seen that peer groups may assume a wider remit than simply generating PDPs and might usefully evolve into something akin to an ‘action learning set’. This concept is borrowed from the business world and Reference SpurrellSpurrell (2000) explains how it has been successfully adapted to set up consultant learning groups in psychiatry.

The final task of the group is to complete whatever paperwork is chosen to document the PDP, countersigning it where necessary and translating it, as needed, to ‘Form E’, which is the record required by the College for those wishing to remain in good standing for CPD.

‘SMART’ educational objectives

Educationalists have generated a useful acronym which sets out the key elements of a learning objective that is likely to be successful. These state that the objectives should be:

Specific

Measurable

Achievable

Realistic

Time-limited.

Generating objectives to meet these criteria is harder than might at first be thought. Colleagues who are not used to this scheme would benefit from tuition from someone who is familiar with the system. ‘Measurability’ is clearly a challenge, especially for those working in mental health. The fundamental task here is to avoid McNamara's Fallacy (named after the ex-US Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara). This refers to the expedient temptation to ‘make the measurable important’ rather than ‘making the important measurable’. Ultimately, some legitimate objectives might defy specificity and measurability, but experience suggests that creative thinking can often lead to surprising achievement in these domains.

There are variations on the SMART acronym. One adds an E for Exciting and an R for Relevant. It goes without saying that hard-pressed doctors are more likely to expend the necessary effort to achieve objectives which meet such additional criteria.

Factors for success

Box 3 lists factors which experience suggests are vital to a positive outcome. ‘Airtime’ refers simply to the need to ensure that all members of the group have sufficient space to consider their requirements and generate an agreed and effective plan. This will rely on some means of ensuring that there is facilitation of the group work. Depending on the size and composition of the group (and how well its members get along) there may be a need to identify one individual to facilitate each meeting, although this role could rotate around group members. It is important that this need is considered and that, if any group member is left feeling that he or she has not had the requisite support from the group, then explicit arrangements are made. Hopefully, unresolved dispute within groups will be unlikely, but in the event, it is essential that there should be a nominated individual (perhaps the trust's CPD coordinator) to act as a reference point for brokering the problem or perhaps to give assistance in making other arrangements for the PDP process.

Box 3 Factors required for successful peer groups and PDPs

-

• Appropriate grouping of practitioners

-

• Between three and eight participants

-

• Regular meetings, at least every 6 months

-

• Agreed structure to meetings

-

• Agreed ‘ground rules’

-

• Guaranteed meeting time: 2–3 hours

-

• ‘Airtime’ for all members

-

• Facilitation role: one individual or shared

-

• Tangible output from the process

The final point in Box 3 (tangible output) requires explanation and probably constitutes the most important criterion for success. Professionals in all walks of life have had to adjust to seemingly ever-increasing regulatory procedures. Many feel that these take precious time away from doing the job in hand and, rightly or wrongly, perceive little benefit in return. There is a real danger that appraisals and PDPs could be seen as just another demand on time, with no payback. If PDPs are to be successful, they will require evidence of making a real impact on the organisations in which they operate, as measured by the support given for necessary training and the efforts made to learn from the information gathered. Psychiatrists in Leeds have agreed that copies of PDPs will be retained for group content analysis, on an anonymous basis, so that collective themes in educational objectives can be identified. This, in turn, informs the educational programme organised by the trust's CPD centre. In this way, PDPs have a real impact on the direction of training and help to ensure that it is truly relevant to the needs of doctors in the organisation.

Conclusions

Personal development plans are set to become an increasingly important aspect of our professional lives. Their role in appraisal will mean that they become the key mechanism by which lifelong learning is planned to ensure that patients’ needs are met as well as our own. Peer groups have proved to be a practicable (and surprisingly enjoyable) mechanism for generating PDPs. Workshop participants have commented on the refreshing opportunity that has been provided to take time out from the hurly-burly of our pressured working lives and reflect with colleagues on reprioritising objectives. To borrow management parlance, they can be truly empowering and provide the ammunition required to argue for educational resources or even changes in working practice.

With attention to the interface with one-to-one appraisal and with proper time given to their operation, peer group PDPs have the capacity to more than repay the effort required to sustain them.

Multiple choice questions

-

1 Revalidation:

-

a will depend on 3 successive years of successful appraisal

-

b will require all consultants to participate in 360-degree appraisal

-

c will be regulated by the GMC

-

d may require audit of appraisal processes

-

e will routinely entail submission of all appraisal paper-work to the GMC.

-

-

2 PDPs:

-

a can be developed one-to-one as well as in peer groups

-

b will be required for the purposes of appraisal

-

c may require modification for changing work circum-stances

-

d are intended to be reactive rather than proactive

-

e have no part in the CPD cycle.

-

-

3 Factors predicting success of PDPs and peer groups include:

-

a ‘airtime’ for all participants

-

b protected time for meetings

-

c the same venue for each meeting

-

d organisational action arising from analysis of PDPs

-

e the same facilitator for all meetings.

-

-

4 Educational objectives are most likely to succeed if they are:

-

a measurable

-

b specific

-

c actuarial

-

d ambidextrous

-

e achievable.

-

-

5 PDPs:

-

a are not required for the College's CPD programme

-

b should be reviewed at least twice per year

-

c should include time limits for achievement

-

d should be agreed only by colleagues working in the same sub-speciality

-

e are mandatory for all NHS staff.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | T | a | T | a | F |

| b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | T | c | T | c | F | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F |

| e | F | e | F | e | F | e | T | e | T |

Fig. 1 The CPD cycle.

Fig. 2 Personal development plan (from Leeds documentation, with permission).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.