In the late third or early second century BC the off-glide of the diphthong /ai/ was lowered to /ae̯/, leading to a change in spelling from <ai> to <ae> (see p. 40).Footnote 1 The use of <ai> for <ae> in inscriptions of the first–fourth centuries AD, especially in genitive and dative singulars of the first declension, is actually not particularly difficult to find, even in quite large numbers (although given the thousands of examples of <ae>, the frequency is probably still very low).Footnote 2 Some, but not all, of these will be due to Greek influence,Footnote 3 misreadings, or mistakes by the stonemason. Use of <ai> seems to have been one of the spellings favoured by Claudius (Reference BiddauBiddau 2008: 130–1), but examples can still be found long afterwards.

It is clear that Quintilian considers the <ai> spelling already highly old-fashioned:

ae syllabam, cuius secundam nunc e litteram ponimus, uarie per a et i efferebant, quidam semper ut Graeci, quidam singulariter tantum, cum in datiuum uel genetiuum casum incidissent, unde “pictai uestis” et “aquai” Vergilius amantissimus uetustatis carminibus inseruit. in isdem plurali numero e utebantur: “hi Sullae, Galbae”.

The syllable ae, whose second letter we now write with the letter e, they used to express differently with a and i, some in all contexts, like the Greeks, others only in the singular, when in the dative or genitive case, whence Virgil, who adored archaism, inserted ‘pictai uestis’ and ‘aquai’ in his poems. In the same words they used e in the plural: ‘hi Sullae, Galbae’.

The <ai> spelling is attributed to the antiqui by Velius Longus (5.4 = GL 7.57.20–58.3), Terentius Scaurus (5.2.2 = GL 7.16.7–10) and Festus (Paul. Fest. 24.1–2) but Marius Victorinus suggests that it may have been in vogue in the fourth century, which is not impossible given its presence in inscriptions, as already mentioned (although Marius recommends his charges always to use <ae>):

ae syllabam quidam more Graecorum per ai scribunt, ne illud quidem custodientes omnes fere qui de orthographia aliquid scriptum reliquerunt praecipiunt, nomina femina casu nominatiuo a finita plurali in ae exire, ut ‘Aeliae’, eadem per a et i scripta numerum singularem ostendere, ut ‘huius Aeliai’, inducti a poetis, qui “pictai uestis” scripserunt, et quod Graeci per i potissimum hanc syllabam scribunt …

Certain people write the syllable ae as ai, in the Greek manner, paying no attention to the teaching of practically everyone whose writing on orthography is preserved, which is that feminine nouns whose nominative is in -a should have plurals ending in -ae, as in Aeliae, but the singular cases in -ai, as in huius Aeliai, following the example of the poets, who wrote ‘pictai uestis’, and because the Greeks wrote this syllable with i …

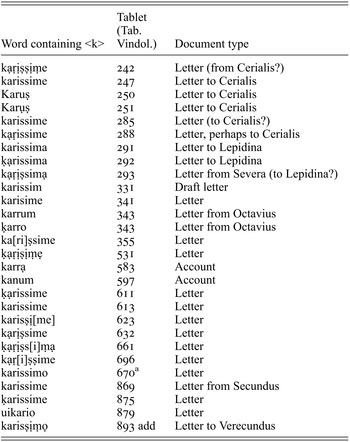

Use of <ai> for <ae> is extremely rare in the corpora. There are only 2 instances in the curse tablets from the first to fourth centuries AD.Footnote 4 The use of Maicius beside Maecius (Kropp 1.7.1/1, mid-first century AD, Altinum) could perhaps be attributed to Greek influence, since many of the names listed on the tablet are Greek. In 1.5.2/1 (around AD 50, Capua) quaistum is the only instance of /ai/ in this tablet, which otherwise shows a number of substandard spellings: ilius for illius, uita for uītam, ipsuq for ipsumque, mado for mandō, Sextiu for Sextius. Greek influence is of course possible, but there is no other internal or external evidence for it.

In the Vindonissa tablets, we have the dative Secundi{i}na<e> (T. Vindon. 41), where only one stroke of the final letter II <e> is observed. Given how rare the use of <ai> is in the corpora it seems unlikely that that it is intended here (although the editor notes the fashionability of <ai> under Claudius). The possibility that the second stroke of the <e> was simply not preserved on the wooden backing of the tablet must be strong.

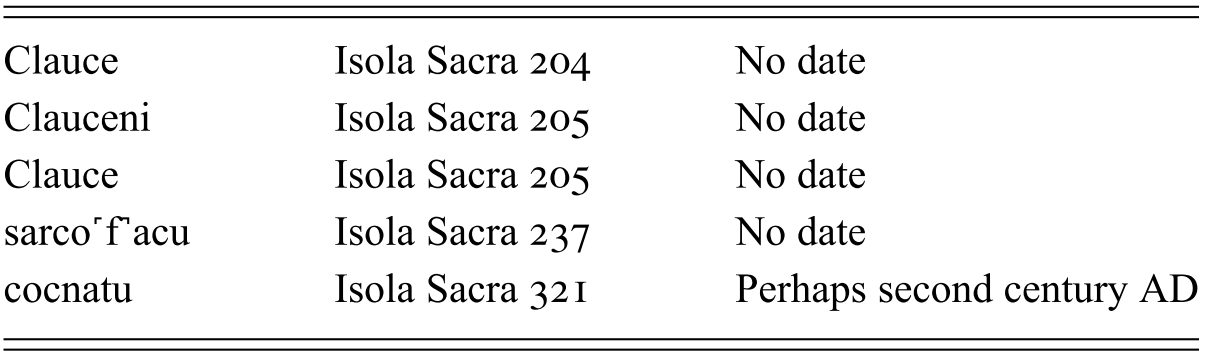

There is also a single example of <ai> in the dative in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, in Marcianai (IS 308, undated). The editors suggest that this is a morphological borrowing from Greek, perhaps to distinguish the dative from the genitive. The (surviving) inscription reads d(is) m(anibus) Marcianai Donatus, so there is no evidence that the composer was a Greek-speaker (nor was the inscription found in situ, so there are no other known inscriptions from the same tomb). It is the case that many of the people commemorated in these inscriptions have Greek names, which sometimes have Greek morphology. There are also three instances of a Latin name with a Greek first declension nominative (Saluiane 89, Manteiane 196, Galitte 288; see Reference AdamsAdams 2003: 490), and there is at least one instance of the hybrid Greek/Latin first declension genitive -aes attached to a Roman name, in Aureliaes (74).Footnote 5 Greek influence, while by no means certain, seems at least as likely as an old-fashioned spelling.

Around the middle of the third century BC, the diphthong /ɛi/ underwent monophthongisation to close mid /eː/; about a century later, this /eː/ was raised further to /iː/, thus falling together with inherited /iː/ (see p. 40). We will see that neither <ei> nor <e> for /iː/ – and for /i/ which results from shortening of /iː/ – are very well attested in the corpora. Nonetheless, even after the first century BC/Augustan period a few plausible examples of each do pop up, in the case of <ei> in one of the Claudius Tiberianus letters, which in general often seem to preserve old-fashioned spelling, and, in the case of <e>, at Vindolanda.

<ei> for /iː/

The effect that this monophthongisation had on spelling was a subject of considerable discussion in the second and first century BC and beyond. The advantage of <ei> was that it provided a spelling that allowed /iː/ and /i/ to be distinguished, but Roman writers disagreed on the exact contexts in which <ei> should be used, with Lucilius, Accius and Varro all apparently taking differing positions (Reference SomervilleSomerville 2007; Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 53–8; Reference Chahoud, Pezzini and TaylorChahoud 2019: 50–3, 57–9, 67–9).

The use of <ei> for /iː/ was still extant in literary contexts towards the end of the first century BC and perhaps later. The Gallus papyrus (Reference Anderson, Parsons and NisbetAnderson et al. 1979), probably from c. 50–20 BC, with the reign of Augustus particularly likely, contains the spellings spolieis for spoliīs, deiuitiora for dīuitiōra, tueis for tuīs and deicere for dīcere, all with <ei> for *ei̯ beside mihi (whose final syllable scans heavy) and tibi (with light final syllable) < *-ei̯;Footnote 1 <ei> for /iː/ is attested in manuscripts of authors as late as Aulus Gellius (13.4.1, writing in the second century AD), along with corruptions which suggest scribes dealing with the unfamiliar spelling (Reference Gibson and ClacksonGibson 2011: 53–4). According to Reference NikitinaNikitina (2015: 58–70), legal texts and ‘official’ inscriptions of the first century BC show a tendency to prefer <ei> for /iː/, especially from original /ɛi/, whereas from the Augustan period there is a clear move to using the <i> spelling, with very occasional instances of <ei>.

The Roman writers on language send mixed messages about the status of <ei>. In the late first century AD, Quintilian says:

diutius durauit, ut e et i iungendis eadem ratione, qua Graeci, ei uterentur: ea casibus numerisque discreta est, ut Lucilius praecipit … quod quidem cum superuacuum est, quia i tam longae quam breuis naturam habet, tum incommodum aliquando; nam in iis, quae proximam ab ultima litteram e habebunt et i longa terminabuntur, illam rationem sequentes utemur e gemina, qualia sunt haec “aurei” “argentei” et his similia.

The habit of joining e and i together lasted rather longer, on the same reasoning as the Greeks used ei: and this usage is decided by case and number, as Lucilius teaches … This is entirely superfluous, because i has the same quality, whether long or short, and sometimes it is actively inconvenient; because in words which end in an e followed by long ī (like aureī and argenteī) we would have to write two es, if we followed this rule [i.e. aureei, argenteei].

It is not clear from this passage whether or not there are contemporaries of Quintilian who still use <ei>; although he only mentions Lucilius, the fact that Quintilian feels the need to argue against it may suggest that in fact there are. The same is true of Velius Longus’ discussion:

hic quaeritur etiam an per ‘e’ et ‘i’ quaedam debeant scribi secundum consuetudinem graecam. nonnulli enim ea quae producerentur sic scripserunt, alii contenti fuerunt huic productioni ‘i’ longam aut notam dedisse. alii uero, quorum est item Lucilius, uarie scriptitauerunt, siquidem in iis quae producerentur alia per ‘i’ longam, alia per ‘e’ et ‘i’ notauerunt … hoc mihi uidetur superuacaneae obseruationis.

Now I turn to the question whether certain words should be written with ei as in Greek. For some have written long instances of i in this way, while others have been content to use an i-longa for this long vowel or to have given it a mark. Still others, among whom is Lucilius, have written it in various ways, since they have written long i sometimes with i-longa and sometimes with ei … This seems to me to be unnecessary pedantry.

However, Charisius (Reference BarwickBarwick 1964: 164.21–29) attributes to Pliny (the Elder) a rule for explaining when third declension accusative plurals are in -eis, suggesting that at least some writers in the first century AD used <ei>, at least in this context, and in the late second or early third century AD, Terentianus Maurus also implies that <ei> is still in use, at least in particular lexemes and endings:

sic erit nobis et ista rarior dipthongos ‘ei’, ‘e’ uidemus quando fixam principali in nomine: ‘eitur in siluam’ necesse est ‘e’ et ‘i’ conectere, principali namque uerbo nascitur, quod est ‘eo’. sic ‘oueis’ plures et ‘omneis’ scribimus pluraliter: non enim nunc addis ‘e’, sed permanet sicut fuit lector et non singularem nominatiuum sciet, uel sequentem, qui prioris saepe similis editur.

For us that diphthong <ei> is rarer, when we see <e> fixed in the original word: in ‘eitur in siluam’ it is necessary to join <e> and <i>, because <e> occurs in the base word, which is ‘eo’. In the same way, we often write ‘oueis’ and ‘omneis’ in the [accusative] plural: here we are not adding an <e>, rather it is retained from the nominative plural so that the reader knows it is not the nominative singular or the case which follows it [i.e. the genitive], which is often identical.

Marius Victorinus (Ars grammatica 4.4 = GL 6.8.13–14) attributes the <ei> spelling to the antiqui, and at 4.59 (GL 6.17.21–18.10) notes that the priores used it to represent the nominative plural of second declension nouns as opposed to the genitive singular. He follows this with the observation that the use of <ei> is a topic which has exercised all writers on orthography, although without making it clear whether any modern writers use it (he himself appears to be opposed).

Diomedes, however, in the late fourth century, is much more explicit that he considers this spelling out of use:

ex his diphthongis ei, cum apud ueteres frequentaretur, usu posteritatis explosa est.

Of these diphthongs, ei, while it was used frequently by the ancients, has been rejected in subsequent usage.

Any kind of conclusive, or even representative, survey of the use of <ei> in the inscriptional context is made extremely difficult by the problems involved in searching on the online databases. The string ‘ei’ in standard spelling represents several sequences of phonemes, while ‘i’ represents (at least) /j/, /i/ and /iː/, all highly frequent phonemes. It is thus extremely difficult to get results which are restricted to the use of <ei> which is desired, and completely impossible to compare it with instances of <i> for /iː/ (and even more impossible, so to speak, to isolate cases of /iː/ < /ɛi/). I carried out a search for the sequence ‘{e}i’ on a plaintext copy of all the inscriptions in the EDCS downloaded on 18/06/2019. After removing cases of <ei> which did not represent /iː/ or /i/, I identified a maximum of 15 dated to the first four centuries AD.Footnote 2 However, this is highly likely to undercount the total instances, partly because of the usual problems with this database, partly because of my own decisions of what to include.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, this does not suggest that <ei> was in common usage in this period (as of 06/04/2021, the database finds 150,594 inscriptions dated from the first to fourth century AD).

In general, the corpora agree with this picture, since <ei> for /iː/ is entirely absent from the Vindonissa, Vindolanda and London tablets, the TPSulp. and TH2 tablets, the Bu Njem ostraca, the Dura Europos papyri, and the graffiti from the Paedagogium.Footnote 4 There are a couple of examples where <ei> is used for the sequence /i.iː/: one in the Caecilius Jucundus tablets ([ma]ncipeis, CIL 4.3340.74, for mancipiīs), in the scribal portion of a tablet which is undated but presumably belongs to the 50s or 60s AD; and one in the Isola Sacra inscriptions (macereis, IS 1, for māceriīs).

There are two possibilities to explain these spellings. The first is that the sequence /i.iː/ has contracted to give /iː/ (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 110). In this scenario, <ei> is being used to represent the remaining /iː/. The second possibility is that the speaker has undergone raising of /ɛ/ to /i/ before another vowel in words like aureus ‘golden’ > /aurius/ (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 102–4). If this were the case, <ei> could be a hypercorrect spelling for /i.iː/. An example of such hypercorrection can be found in Terenteae for Terentiae in another Isola Sacra inscription (IS 27). There is no way to distinguish between these possibilities: neither inscription shows any other old-fashioned or substandard features (and nor do any of the other inscriptions from the same tomb, in the case of IS 1).

Otherwise, only the curse tablets and letters provide a certain amount of evidence for the continuing use of <ei> either to represent /iː/, [ĩː],Footnote 5 or etymological /iː/ which became /i/ by iambic shortening (on which, see p. 42), in words like ubi ‘when’ < ubī < ubei.Footnote 6

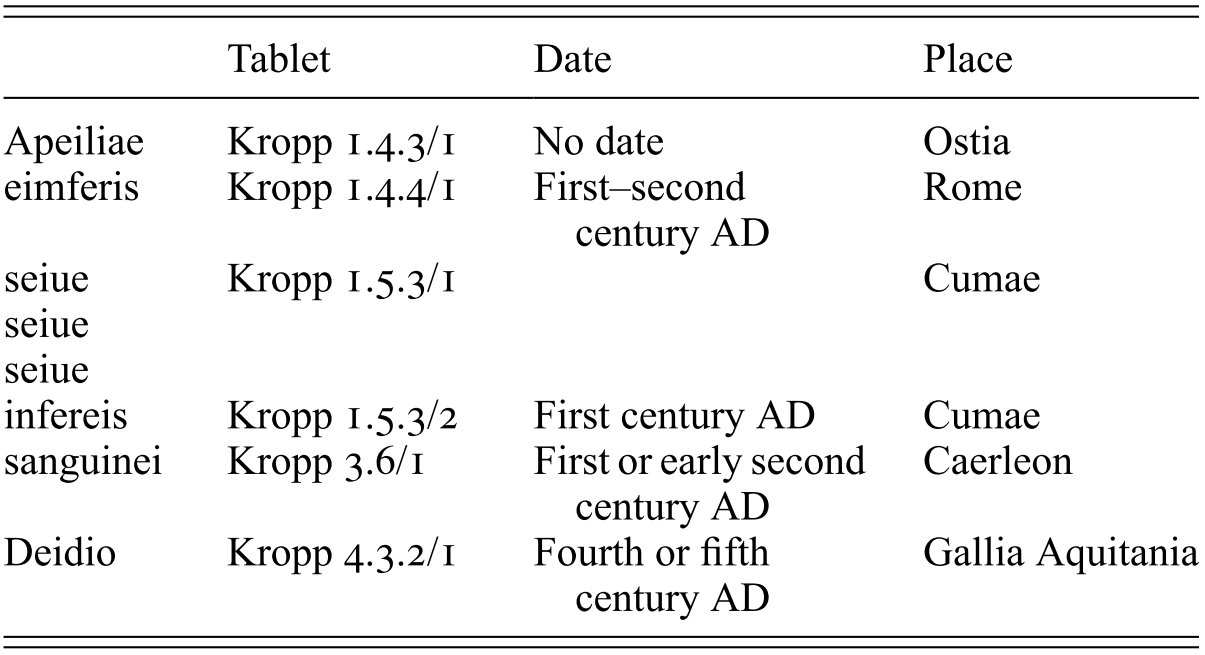

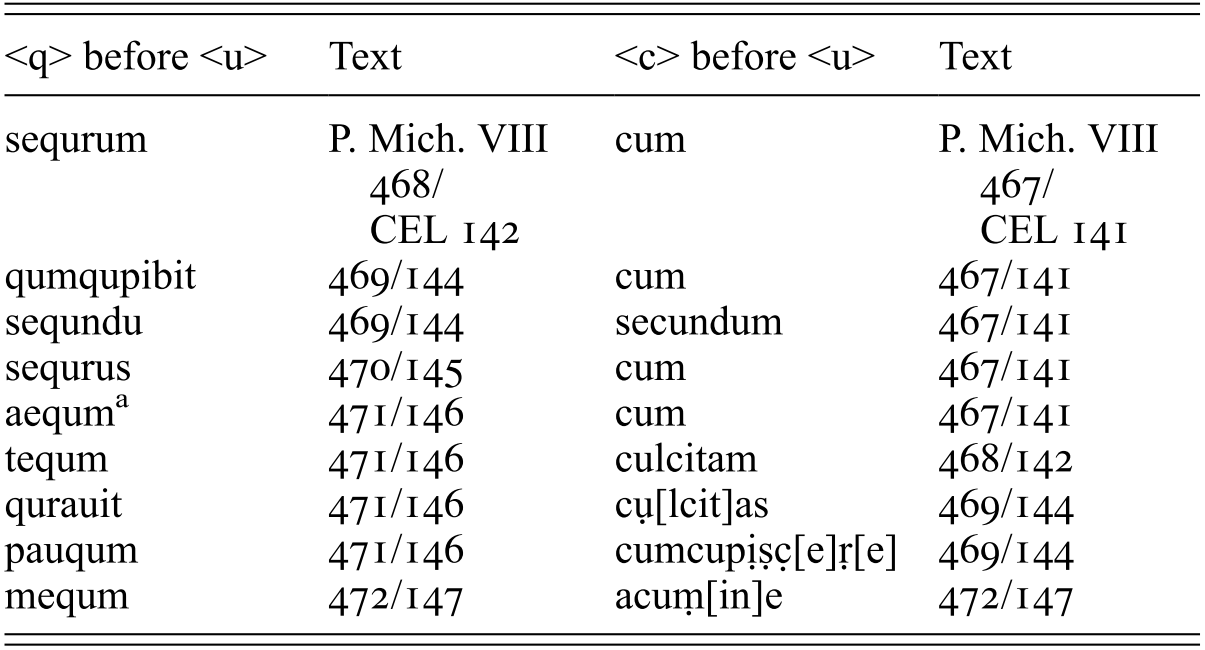

In the curse tablets <ei> is found, on the whole, in fairly early texts: in Kropp 10.1.1, from the later second century BC, and 1.4.4/3, 1.4.4/8, 1.4.4/9, 1.4.4/10, 1.4.4/11, 1.4.4/12, 2.1.1/1, 2.2.3/1, all from the first century BC, <ei> is used frequently (but not necessarily consistently), including for iambically shortened /i/ in tibei (1.4.4/3). There are a handful of other examples, although some are in undated tablets (see Table 1).Footnote 7 1.4.4/1, dated to the first two centuries AD, has the spelling suom twice, and otherwise is entirely standard (including nisi, whose final vowel would have been /iː/ prior to iambic shortening). 1.5.3/2 has largely standard spelling, though it is possible that the writer had the /eː/ and /i/ merger, given the spellings Caled[um, Cale[dum] for Calidum and niq[uis] for nēquis and possible ni[ue for nēue if correctly restored. However, the author could also be using the variant nī for nē in the latter two. In 3.6/1, sanguinei reflects the (originally i-stem) ablative *-īd; <i> is used for the iambically shortened final vowel of tibi and for /iː/ in ni ‘if not’. Substandard spellings are found in domna for domina and hyper-correct palleum for pallium. In the case of the very late Deidio (4.3.2/1), the use of <ei> may have been preserved in the family name: <i> is used for /iː/ in oculique. The writer shows substand-ard spelling in bolauerunt for uolāuē̆runt and pedis for pedēs.

Table 1 <ei> in the curse tablets, undated and first to fourth (or fifth) century AD

| Tablet | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apeiliae | Kropp 1.4.3/1 | No date | Ostia |

| eimferis | Kropp 1.4.4/1 | First–second century AD | Rome |

| Kropp 1.5.3/1 | Cumae | |

| infereis | Kropp 1.5.3/2 | First century AD | Cumae |

| sanguinei | Kropp 3.6/1 | First or early second century AD | Caerleon |

| Deidio | Kropp 4.3.2/1 | Fourth or fifth century AD | Gallia Aquitania |

Likewise, in the letters most examples of <ei> are found in texts dated to the first century BC or the Augustan period. In the case of CEL 3, from the second half of the first century BC, the writer seems not to have learnt the rule of when to use <ei> well, deploying it for short /i/ in sateis for satis and defendateis for dēfendātis alongside /iː/ in s]ẹi for sī and conserueis (twice) for conseruīs. If the author Phileros is also the writer he may not have been a native speaker of Latin. CEL 12, dated to 18 BC, has <ei> in eidus for īdūs. CEL 10, from the Augustan period, includes <ei> for iambically shortened /i/ in tibei beside <i> in mihi, and, mistakenly, in the second person singular future perfect uocāreis for uocaris by confusion with the perfect subjunctive uocārīs. Alongside these, the genuine cases of /iː/ (originally < /ɛi/) in quī and sī are spelt with <i>. This letter is characterised by both conservative spelling features alongside substandard orthography (on which, see pp. 10–11). CEL 13, from the early first century AD, includes tibei (beside tibi); other instances of etymological /ɛi/ are spelt with <i>in ịḷḷịṣ and ṣc̣ṛịp̣si.

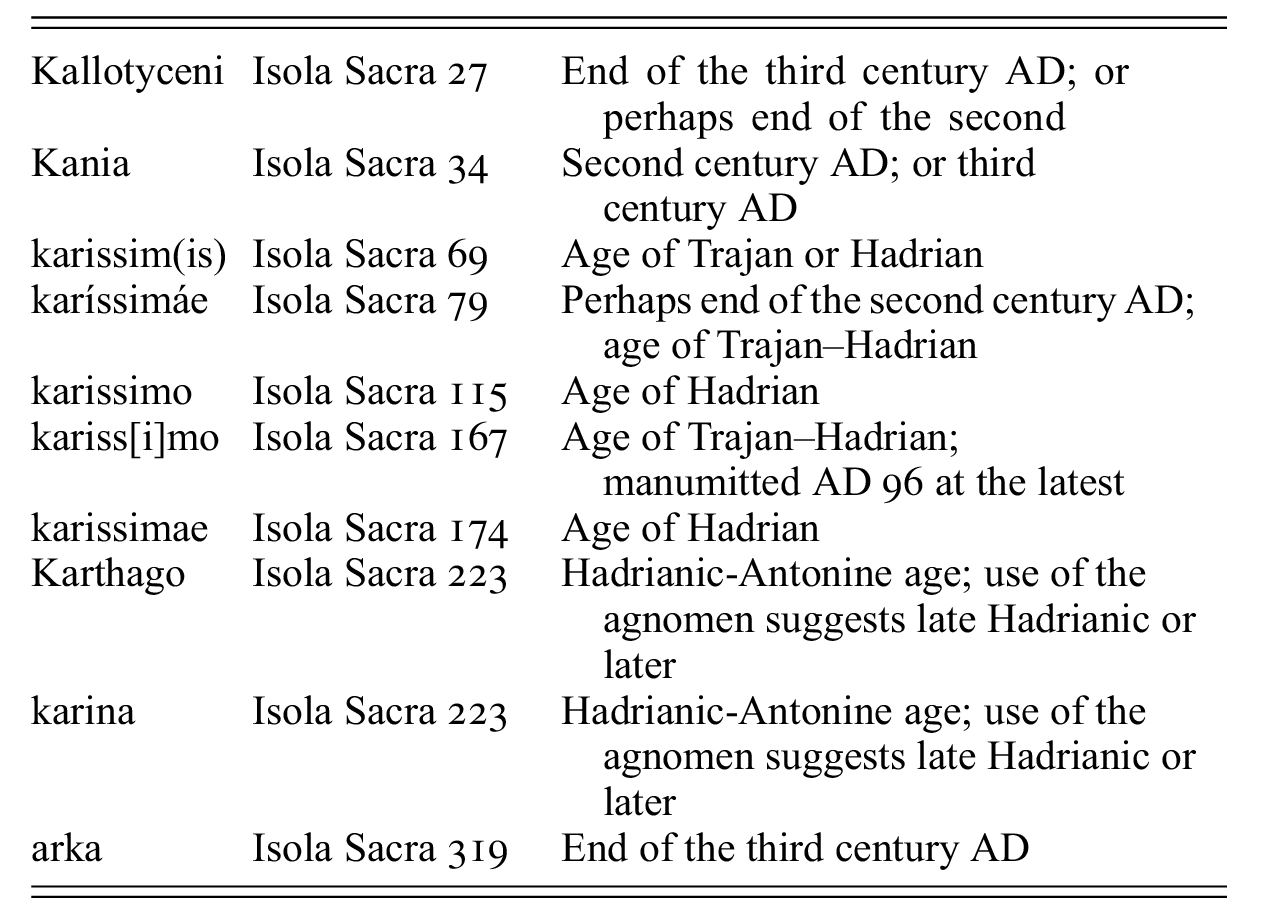

Probably the latest example of <ei> in the corpora is reṣc̣ṛeibae (P. Mich. VIII 469.11/CEL 144) for rescrībe in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, in which most other instances of /iː/ are spelt <i>, including original /ɛi/ in uidit, [a]ttuli, tibi (with iambic shortening). This letter also includes three instances of the dative singular of illa written illei, as well as ille[i]. This could represent Classical illī but scholars have instead suggested that it be understood as an innovative feminine dative /illɛːiː/ which lies behind Romance forms such as Italian lei ‘she’ (Cugusi, in the commentary in CEL; Reference AdamsAdams 1977: 45–7; Reference Adams2013: 459–64).Footnote 8 Adams makes the point that in the other letters of the Claudius Tiberianus archive the masculine dative is always spelt illi, and that illei in this letter is therefore more likely to be a specifically feminine form. This is not a strong argument, however, since none of the other Tiberianus letters is written by the same hand. None of the other scribes uses <ei> at all, while that of 469/144 also uses it in reṣc̣ṛeibae. So the fact that in the other letters the masculine dative is illi tells us nothing about the spelling illei in 469/144.

Similar forms appear in the letters of Rustius Barbarus from the first century AD: a feminine dative illei (CEL 75), and a genitive illeius (CEL 77), the gender of whose referent cannot be determined. Nowhere else in these ostraca written by the same hand is there any example of /iː/ being spelt with <ei> (and there are very many examples of /iː/); this includes one instance of illi (in the same letter 77, probably masculine). Now, it is conceivable that this has something to do with the unique genitive and dative endings of pronouns: perhaps <ei> was preserved as a spelling in the educational tradition to mark out these curious endings; this would be particularly relevant in the genitive where original illīus underwent shortening to illius. The spelling with <ei> could then preserve a memory of the original length. However, in this case, given the existence of other evidence for similar feminine genitive and dative forms in Latin put forward by Adams, and the absence of other instances of <ei> for /iː/ in Rustius Barbarus, there is a strong possibility that illei and illeius represent special feminine forms rather than illī and illīus. Since these forms are therefore present in a corpus of similarly early date, it cannot be ruled out that illei in the Claudius Tiberianus letter is also a form of this type, rather than having <ei> for /iː/.

<e> for /iː/

In addition to the continuing use of <ei> for /iː/, <e> too apparently remained an infrequent possibility to represent /iː/. Quintilian provides the relevant examples leber for līber and Dioue Victore for Iouī Victorī in his list of old spellings at Institutio oratoria 1.4.17, implying that they are no longer in use, and I have not found any other reference in the writers on language. There are significant difficulties in finding examples of <e> for /iː/ in the epigraphic record as a whole; I have found 114 instances on LLDB in the first four centuries AD.Footnote 9 This number is almost certainly too high since some cases will be things like a mistaken use of the ablative -e in place of dative -ī, and many examples are for original /iː/, not from /ɛi/: these may be hypercorrect of course, but may also suggest that a different explanation should be sought. Nonetheless, these results imply that the <e> spelling did survive to some extent, although the spellings with <e> must represent a tiny proportion of all instances of <i> for /iː/.

Unsurprisingly, then, in the corpora there are only a very small number of examples of <e> for /iː/, of which a couple are very plausible. One is deuom (CEL 10) for dīuom ‘of gods’ in Suneros’ letter from the Augustan period characterised by conservative as well as substandard spelling (see pp. 10–11). Another is amẹcos (Tab. Vindol. 650) for amīcōs ‘friends’ in a letter at Vindolanda authored by one Ascanius who was apparently a comes Augusti, and hence of relatively high rank. The text is all in a single hand, but we cannot tell if it was that of Ascanius himself or a scribe. The letter was sent to Vindolanda and therefore does not necessarily reflect the same scribal tradition. The spelling is all otherwise standard, as far as we can tell. Reference AdamsAdams suggests (2003: 535) that the maintenance of pronunciation of /eː/ < /ɛi/ ‘was seen as a regionalism and belonged down the social scale’, but this does not fit well with the social context of the Vindolanda letter (although of course it could be a feature of the scribe’s Latin rather than Ascanius’).Footnote 10 However, Festus (Paul. Fest. 14.13) notes amecus as an old spelling,Footnote 11 so it may be better to see the spelling as old-fashioned.

In the curse tablets, a first century BC instance of <e> for /iː/ may be nesu (Kropp 1.4.2/2), if this stands for nīsum ‘pressure, act of straining’, although this text has a number of errors of writing (see p. 132 fn. 2).Footnote 12 Otherwise we find only 4 instances of <e>, all from Britain: deuo for dīuō (Kropp 3.15/1, 3.19/3) ‘god’, demediam (3.15/1) for dīmidiam ‘half’, and requeratat (3.7/1) for requīrat ‘may he seek’. Reference AdamsAdams (2007: 602) suggests that deuo could reflect a British pronunciation of deo ‘god’, or be a code-switch into British Celtic, for which dēuos would have been the word for ‘god’;Footnote 13 at any rate, it is not a good example of <e> for old-fashioned /iː/. We could have a hypercorrect old-fashioned spelling with <e> for /iː/ < *ī in demediam, but perhaps instead one should think of confusion between the prepositions dī- and dē-. Nor is requeratat a plausible example, since the writer of the text has made a large number of mistakes in the writing of the text (as distinct from substandard spellings), such as memina for fēmina, capolare for capitulāre, pulla for puella, uulleris for uolueris, llu for illum, Neptus for Neptūnus etc.

In the tablets of the Sulpicii, C. Novius Eunus writes dede (TPSulp. 51.2.13) for dedī‘I gave’. This could well be an old-fashioned spelling, since Eunus uses other old-fashioned spellings (see pp. 187, 202–4, and 262).Footnote 14 But we could also imagine repetition of the first syllable by accident (and Eunus is prone to mechanical errors in his writing, as shown by ets, 51.2.9, for est, Cessasare, 52.2.1, for Caesare, and stertertios, 68.2.5, for sestertiōs).

In the Isola Sacra inscriptions, there is one example of coniuge (IS 249, second–third century AD) in place of dative coniugī ‘for his wife’. There are no other substandard features in this short text, but perhaps this is a slip into the ablative (or even the accusative with omission of final <m>) rather than an old-fashioned spelling. The dative ending is spelt with <i> in merenti ‘deserving’.

A much more complicated situation arises where <e> represents short /i/ from long /iː/ by iambic shortening (see p. 42) or other types of shortening. This could be an old-fashioned spelling, reflecting the mid-point of the development /ɛi/ > /eː/ > /iː/. But from the first century AD onwards, at least some speakers in certain contexts use <e> for /i/, presumably due to a lowering of /i/ to [e] and the raising of (original) /ɛː/ to /eː/; with the loss of vowel length distinctions these phonemes would end up falling together as /e/ in the precursor of most Romance varieties (see p. 40). In cases where original /ɛi/ > /eː/ > /iː/ underwent iambic or other types of shortening, it is then difficult to tell whether <e> for <i> is old-fashioned or substandard, and each example needs careful investigation.

Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 51–5) entertains the possibility that several <e> spellings in the Rustius Barbarus and Claudius Tiberianus letters may be old-fashioned, and notes the following observation by Quintilian:

“sibe” et “quase” scriptum in multorum libris est, sed, an hoc uoluerint auctores, nescio: T. Liuium ita his usum ex Pediano comperi, qui et ipse eum sequebatur. haec nos i littera finimus.

Sibe and quase are written in the books of many authors, but I do not know whether this is what the authors intended: I have learnt from Pedianus – who followed him in doing this – that Livy used these spellings. We write these words with a final i.

Quintilian clearly thought this spelling was old-fashioned (in addition to what he says in this extract, it forms part of a list of archaic spellings), and Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 54) follows him, saying that ‘[i]t is inconceivable that Livy and other literary figures used such spellings as a reflection of a proto-Romance vowel merger that was taking place in speech. They must have been using orthography with an old-fashioned flavour to it’.Footnote 15 According to Adams, use of <e> is retained from the time when sibi was still /sibeː/.

However, I have my doubts about this. Quintilian himself is aware, as shown by his comment ‘sed, an hoc voluerint auctores, nescio’, that it was possible for an author’s spelling to become corrupted by subsequent copyists (as noted by Reference De MartinoDe Martino 1994: 743). It is striking that the examples given by Quintilian are of <e> in absolute word-final position. Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 51–62, 67) has identified /i/ in closed word-final syllables as showing evidence of lowering to [e] in the first and second centuries AD. The apparent frequency of <e> in words like tibe and nese might instead be taken as showing that this lowering also affected /i/ in absolute word-final position. If lowering of /i/ to [e] had already happened, at least in words like sibi and quasi, by the first century AD, it is not impossible that it could have entered the manuscript tradition of earlier literary authors by the time of Quintilian.

In either case, it is probably not coincidental that the words in question all involve final /i/ resulting from iambic shortening. If Adams is right that this is an archaism, the old-fashioned spelling could have been retained in these words because iambic shortening applied to forms like /sibeː/ and produced a variant /sibe/; after /sibeː/ became /sibiː/ (and then /sibi/) the standard spelling sibi followed, but sibe remained as an alternative spelling.Footnote 16 This would explain, for example, why <e> is only found to write synchronic short /i/ in tibe in the Rustius Barbarus letters, despite a large number of instances of synchronic /iː/ < /ɛi/, which is what we might expect an old-fashioned use of <e> to represent. If, on the other hand, <e> in these words is due to lowering of /i/ in final syllables, it is also not surprising that the examples are in originally iambic words: iambic shortening of /iː/ is one of the very few sources of absolute word-final short /i/ in Latin.

The explanation by lowering seems particularly likely in the case of the Rustius Barbarus letters. As Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 55) notes, ‘these letters are very badly spelt, with no sign of hypercorrection or other old spellings, and there is an outside chance that tibe here is a phonetic spelling’. We find 4 examples of the spelling tibe (CEL 73, 74, 76, 77) for tibi beside 8 of tibi (these are the only examples of absolute word-final short /i/ in the letters). This compares with 4 (certain) examples of <e> for /i/ in final closed syllables of a polysyllabic word (scribes for scrībis ‘you write’, CEL 74, scribes, mittes for mittis ‘you send’ 75, scribes 76),Footnote 17 and 6 examples with <i> (dixit, enim 73, talis, leuis 74, possim 75, traduxit 77). The rate at which <e> is written for /i/ in these contexts is therefore almost identical,Footnote 18 so it makes sense that the same explanation, lowering of /i/ to [e] in final syllables, should apply to both. Consequently, it seems more probable that the tibe spellings are substandard rather than old-fashioned.

The same explanation could pertain in most of the other examples of <e> for /i/ by iambic shortening in the corpora, and cannot be ruled out in any of the examples I now discuss, from the tablets of the Sulpicii, the Isola Sacra inscriptions and the Vindolanda tablets.

In the tablets of the Sulpicii we find ube for ubi < ubei ‘when’ in the chirographum of Diognetus, slave of C. Novius Cypaerus (TPSulp. 45.3.3, AD 37). Although there are no other examples of <e> for /i/ in final syllables, Diognetus also spells leguminum ‘of pulses’ as legumenum, suggesting that /i/ may have been lowered to [e] more generally in his idiolect (although short /i/ is otherwise spelt correctly several times, including in a final syllable in two instances of accepit).Footnote 19 There are two examples of sibe in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, and these too are likely to be due to lowering. IS 27 contains several other substandard spellings, including Terenteae for Terentiae, filis for filiīs, qit for quid, aeo for eō. IS 337 has mea for meam and nominae for nōmine. These may reflect carelessness on the part of the engraver rather than lack of education, since mea comes at the end of a line (and in space created by erasure of a previous word or words), while nominae follows poenae and looks like the result of eyeskip. But the same carelessness could presumably have allowed <e> to be used, reflecting his pronunciation, instead of <i> in his copy of the text.

In the Vindolanda tablets ụbe (Tab. Vindol. 642) for ubi is the only instance of <e> for short word-final /i/.Footnote 20 The spelling in this tablet seems otherwise standard, and note in particular an instance of ṭibi. Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 91; Reference Adams2003: 533–5) has emphasised the general lack of confusion between /i/ and /eː/ in the Vindolanda tablets. But given that this appears to be the only text written in this hand, it was probably not written by a Vindolanda scribe,Footnote 21 and that it has no other examples of /i/ in a word-final syllable, we cannot be absolutely sure that <e> is not due to lowering rather than being old-fashioned.

The final case of <e> for short final /i/ is nese (P. Mich. VIII 468/CEL 142, and CEL 143) for nisi in the Claudius Tiberianus archive. Could this be due to lowering? In 468/142, there are two other instances of <e> for <i>, both in a final syllable: uolueret for uoluerit ‘(s)he would have wanted’ and aiutaueret for adiūtāuerit ‘(s)he would have helped’ (beside 3 cases of <i>: nihil, [ni]hil, and misit). But apart from nese there are 10 examples of short /i/ spelt <i> in an open final syllable: tibi (twice), [ti]bi, ṭibi, mihi (4 times), [mih]i, sibi. In CEL 143, written by the same scribe, apart from nese there are no other instances of <e> for /i/, and 5 of short /i/ in an open final syllable: tibi (twice), mihi (twice), miḥi. On the one hand, therefore, the writer of these texts did seem to have lowering in word-final syllables followed by a consonant. On the other, nese is the only example of possible lowering of /i/ in absolute word-final position, compared to 15 examples spelt with <i>. I am not certain whether use of <e> is due to lowering or is old-fashioned.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the letters include some further instances of <e> being used for /i/ which are not due to iambic shortening but could also reflect old-fashioned spellings. The first vowel of sene (468/142) for sine was originally /i/, but the writer may have thought of sine as being connected with sī ‘if’. A hypercorrect spelling seine (CIL 12.583), presumably resting on this false etymology, is attested in the second century BC. The forms nese, nesi in 468/142, and nese in 143 also have <e> for /i/ in their first syllable. This could be an old-fashioned spelling accurately reflecting original /ɛ/ here, since nisi probably came from *ne sei̯ (Reference FriesFries 2019: 94–7). The spelling nesei is attested in the two copies of the Lex luci Spoletina (CIL 12.366 and 12.2872, probably from the mid-second century BC), and nesi is mentioned by Festus (Fest. 164.1).Footnote 22 Alternatively, it could be a hypercorrection, with analysis of the ni- in nisi as being derived from the alternative negative nī < /neː/ < /nɛi/.

However, given that the writer (or author, dictating) of the text does have lowering of /i/ to [e], at least in final syllables followed by a consonant (i.e. in a position of minimal stress: Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 60), it is still possible that it is lowering that is to blame for the spelling with <e> in sine, nese, nesi, especially because these are function words, which are particularly likely not to receive phrasal stress (see p. 42), and hence might have undergone the same lowering seen in the final syllable despite not being in the final syllable of the word.

There is not enough evidence to draw completely certain conclusions. However, I do not think that we can be sure that the various types of <e> for /i/ used by the writer of P. Mich. VIII 468/CEL 142 and CEL 143 are to be attributed to old-fashioned spelling (which would be of several different types). I would be inclined to explain all instances as due to lowering of /i/ to [e] in relatively unstressed position (in function words and in final syllables).

There are a number of processes which led to the possibility of using <o> as an old-fashioned spelling to represent /u/. I will begin by discussing examples which may be attributed to the following sound changes:

(1) /ɔ/ in final syllables was raised to /u/ before most consonants and consonant clusters in the course of the third century BC, e.g. Old Latin filios > filius ‘son’;

(2) /ɔ/ was raised to /u/ in a closed non-initial syllable during the second century BC, e.g. *eontis > euntis ‘going (gen. sg.)’;

(3) /ɔ/ > /u/ before /l/ followed by any vowel other than /i/ and /eː/ in non-initial syllables (Reference SenSen 2015: 15–28), e.g. *famelos > *famolos > famulus ‘servant’ (cf. familia ‘household’).

For various reasons, including the relatively late confusion of /ɔː/ and /u/ discussed directly below, and the difficulty of removing false positives from searches in the database, trying to establish the rate at which old-fashioned <o> for /u/ appears in the epigraphic spellings of the first four centuries AD is not practical. In his list of changes wrought by time, all of which seem to be seen as deep archaisms, Quintilian includes some examples of type (1):

quid o atque u permutata inuicem? ut “Hecoba” et “nutrix Culchidis” et “Pulixena” scriberentur, ac, ne in Graecis id tantum notetur, “dederont” et “probaueront”.

What about o and u taking each other’s place? So that we find written Hecoba for Hecuba and nutrix Culchidis for Colchidis, and Pulixena for Polyxena, and, so as not to only give examples from Greek words, dederont for dederunt and probaueront for probauerunt.

Apart from after /u/, /w/ and /kw/, where the raising of /ɔ/ was retarded until the first century BC, which is discussed below (Chapter 8), there are few cases of <o> for <u> arising from these contexts in the corpora. Even where we do find <o>, a confounding factor in identifying old-fashioned spelling of /u/ of these types is the lowering of /u/ to [o] which eventually led in most Romance varieties to the merger of /u/ and /ɔː/. According to Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 63–70), this can be dated to between the third and fifth centuries AD, and did not take place at all in Africa.Footnote 1 This requires him to identify a number of forms which show <o> for /u/ as containing old-fashioned spelling (or having other explanations) in the Claudius Tiberianus letters (Reference AdamsAdams 1977: 9–11, 52–3; Reference Adams2013: 63–4).

He sees posso (P. Mich. VIII 469/CEL 144) not as a rendering of possum, but a morphological regularisation with the normal first singular present ending which shows up elsewhere; this is quite plausible. Also plausible, given the spelling with final <n>, is the influence of the preverb con- on the preposition cum, which is spelt con in 468/142 (8 times) and 471/146 (twice), but old-fashioned spelling could also be a factor.

The origin of the adverb minus ‘less’, is extremely uncertain. It could go back to *min-u-s, since /u/ is also found in the stem of the related verb minuō ‘I lessen’; this may also be the origin of the neuter of the comparative minor ‘smaller, lesser’ (Reference LeumannLeumann 1977: 543; Reference SihlerSihler 1995: 360). If this is correct, the <o> in the final of quominos (470/145) would not be old-fashioned. But alternative explanations would see adverbial minus and the neuter of the comparative both coming from *minos > minus (although this would have to be somehow secondary, since the usual comparative suffix is *-i̯os-; Reference MeiserMeiser 1998: 154; Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 384). If minus does come from *minus rather than *minos, quominos could be a false archaism, by influence from comparative minus, since the neuter of comparative adjectives normally did come from *-i̯os-.

However, sopera (471/146) for supra certainly never had *o in the first syllable. Reference AdamsAdams (1977: 10–11) originally saw <o> here as due to the merger of /u/ and /ɔː/, but subsequently (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 64) suggests that the scribe may have seen <o> as also being old-fashioned, bolstered by the possibility that the lack of syncope is also an old-fashioned feature (supera is found in Livius Andronicus, in Cicero’s Aratea and in Lucretius; Adams loc. cit. and OLD s.v. supra).Footnote 2 It is of course not impossible that the scribe was hypercorrect here, but in the absence of other evidence for this false etymology this explanation is not particularly appealing.

In my view, it is more likely that sopera, and perhaps quominos, suggests that either the author, Claudius Terentianus, or the scribe, was an early adopter of lowered [o] for /u/ (and note that both cases of <o> are in paradigmatically isolated formations which may have made it difficult for the scribe to identify which vowel was involved).Footnote 3 It is also possible that one or both were not native speakers of Latin, which may also have led to problems in identifying the vowel for the scribe.

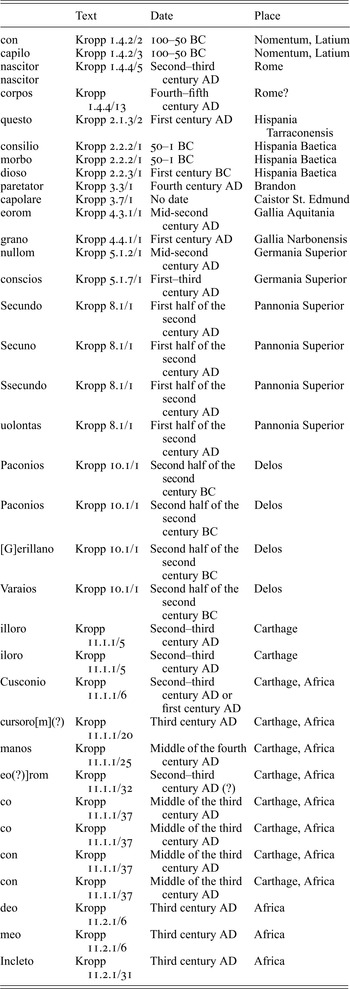

There are quite a number of cases of <o> for /u/ in the curse tablets (see Table 2), but I am doubtful of how many really reflect archaisms. con (Kropp 1.4.2/2), con (twice), co (twice, 11.1.1/37) for cum can be explained in the same way as in the Tiberianus letters, while second declension nominative singular masculine forms in -o(s) may be due to influence from other languages: Celtic in the case of Secundo, Secuno, Ssecundo (8.1/1, Pannonia, first half of the second century AD), if it really represents Secundus.Footnote 4 This tablet also has uolontas for uoluntās, but it uses <u> for /o/ in lucuiat (apparently for loquiat or loquiant, an active equivalent of loquātur or loquantur), as well as a number of spellings which cannot be explained as due to normal features of spoken Latin (<i> for /ɛ/ in ageri for agere and limbna for lingua), so we cannot be sure uolontas does not arise from the writer’s problems with spelling or abnormal phonology.

Table 2 <o> for /u/ in the curse tablets

| Text | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| con | Kropp 1.4.2/2 | 100–50 BC | Nomentum, Latium |

| capilo | Kropp 1.4.2/3 | 100–50 BC | Nomentum, Latium |

| Kropp 1.4.4/5 | Second–third century AD | Rome |

| corpos | Kropp 1.4.4/13 | Fourth–fifth century AD | Rome? |

| questo | Kropp 2.1.3/2 | First century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| consilio | Kropp 2.2.2/1 | 50–1 BC | Hispania Baetica |

| morbo | Kropp 2.2.2/1 | 50–1 BC | Hispania Baetica |

| dioso | Kropp 2.2.3/1 | First century BC | Hispania Baetica |

| paretator | Kropp 3.3/1 | Fourth century AD | Brandon |

| capolare | Kropp 3.7/1 | No date | Caistor St. Edmund |

| eorom | Kropp 4.3.1/1 | Mid-second century AD | Gallia Aquitania |

| grano | Kropp 4.4.1/1 | First century AD | Gallia Narbonensis |

| nullom | Kropp 5.1.2/1 | Mid-second century AD | Germania Superior |

| conscios | Kropp 5.1.7/1 | First–third century AD | Germania Superior |

| Secundo | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Secuno | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Ssecundo | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| uolontas | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Paconios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| Paconios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| [G]erillano | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| Varaios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| illoro | Kropp 11.1.1/5 | Second–third century AD | Carthage |

| iloro | Kropp 11.1.1/5 | Second–third century AD | Carthage |

| Cusconio | Kropp 11.1.1/6 | Second–third century AD or first century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| cursoro[m](?) | Kropp 11.1.1/20 | Third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| manos | Kropp 11.1.1/25 | Middle of the fourth century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| eo(?)]rom | Kropp 11.1.1/32 | Second–third century AD (?) | Carthage, Africa |

| co | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| co | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| con | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| con | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| deo | Kropp 11.2.1/6 | Third century AD | Africa |

| meo | Kropp 11.2.1/6 | Third century AD | Africa |

| Incleto | Kropp 11.2.1/31 | Third century AD | Africa |

The fairly late date of cor]pos (1.4.4/13) for corpus and paretator (3.3/1) for parentātur allow them to be attributed to lowering of /u/; both also contain other substandard spellings. Undated capolare and capeolare (3.7/1) for capitulāre could also be due to lowering (in an inscription whose spelling is anyway highly deviant). And nascitor for nascitur (twice, 1.4.4/5), dated to the second or third centuries AD, could also be a precocious example of this; so could conscios (5.1.7/1) for conscius if it belongs towards the end of its date range. Both contain other substandard spellings. Having accepted that [o] for /u/ might be attested in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, I would suggest that this may also be a possibility for eorom (4.3.1/1) for eōrum, and nullom (5.1.2/1) for nūllum, also from the second century AD. The preponderance of cases in the final syllable might point to lowering occurring there first, in parallel to the situation of /i/ to [e].

Given their datings to the first century BC and first century AD, capilo (1.4.2.3) for capillum, questo (2.1.3/2) for quaestum, cos[i]lio, morbo (2.2.2/1) for cōnsilium, morbus, dioso (2.2.3/1) for deorsum, granom (4.4.1/1) for grānum could be old-fashioned spellings. Some of these texts also contain substandard spellings. None of them is in a context in which a mistake of ablative for nominative or accusative is very easy to envisage.

If Adams is right that the lowering of /u/ to /o/ did not take place in Africa (but see footnotes 1 and 10), old-fashioned spelling becomes a plausible explanation for a few instances there of <o> for /u/ from the second to third centuries AD. Incleto for Inclitum (11.2.1/31) I attribute to influence from the Greek second declension ending -ον, since the text has other examples of interference from Greek spelling.Footnote 5 11.1.1/32 has eo(?)]rom for eōrum, but in addition to substandard spellings has a number of mechanical errors. So does 11.2.1/6, and there is also the possibility that p]er deo meo reflects an error in what case goes with per rather than an old-fashioned spelling of deum meum. The other example of a noun following per in this text is Bonosa for Bonōsam, so the author may have thought that per took the ablative. But we do find illoro, iloro for illōrum (11.1.1/5), Cusconio for Cuscōnium (11.1.1/6), cursoro[m] for cursōrum (11.1.1/20). There is no reason to imagine that Cusconio is an ablative since it forms part of a list of four names in the accusative. Many of these texts also contain substandard spellings.Footnote 6

Overall, it is striking how many cases of <o> for /u/ there are in the curse tablets. I am reluctant to see them all as old-fashioned features, especially since few of the texts show any other such spellings; in practically all of the texts there are several other endings in -us or -um, and there seems no reason why a single word should be marked out in this way, especially in cases like the three names in sequence Cosconio Ianuarium et Rufum (11.1.1/6). I have more sympathy than Adams does with the idea that we may be seeing early signs of the lowering of /u/ to [o] that is better evidenced in much later texts; one could even suppose that in African Latin /u/ did lower to [o] in final syllables as elsewhere, but since /ɔː/ did not merge with /u/, [o] simply remained an allophone of /u/. One should also note that the intrinsic difficulties in the writing and reading of (often very damaged) curse tablets do make them more unreliable than other types of epigraphic evidence (Reference KroppKropp 2008a: 8).Footnote 7 On the other hand, all the examples of <o> for /u/ from the curse tablets do come from original /ɔ/, unlike with sopera and perhaps quominus in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, and a few of them are very early compared to the emergence of good evidence for the merger of /ɔː/ and /u/. So I do not rule out the possibility that some of these <o> spellings are old-fashioned.

There is one Augustan example of <o> for /u/ < /ɔ/ in the letters, in the form of Dìdom (CEL 8, 24–21 BC), which appears to represent the name Didium. It seems strange that an old-fashioned spelling should be used here but not in the name [I]ucundum with which it is conjoined (or indeed in the other accusative singular second declension form in this letter, decrìminatum), but no other explanation arises.Footnote 8 Another damaged letter (CEL 166, around AD 150) has epistolám, which is reasonably likely to be an old-fashioned spelling (assuming this is not an early example of lowering of /u/).

There are two possible examples in the Bu Njem ostraca, but kamellarios (O. BuNjem 76) is very uncertain: it could be a nominative singular for accusative, which is common in the ostraca (Reference AdamsAdams 1994: 96–102), but could also be an accusative plural (this is how Adams understands it). The other is ]isṭolạ[ (114), which may reflect epistola for epistula; but apart from the fact that the reading is not certain, there is a certain amount of evidence for confusion between /ɔː/ and /u/ at Bu Njem (see fn. 10).

Another case of <o> for <u> occurs in cui, the dative singular of the relative pronoun quī and the indefinite pronoun quis. An older form is quoiei (CIL 12. 11, 583, 585) and it had come to be spelt quoi around the start of the first century AD, according to Quintilian:

illud nunc melius, quod “cui” tribus, quas praeposui, litteris enotamus, in quo pueris nobis ad pinguem sane sonum qu et oi utebantur, tantum ut ab illo “qui” distingueretur.

We now do better to spell cui with three letters, as I have given it here. When I was a boy, they used qu and oi, reflecting its fuller sound, just for the purpose of distinguishing it from qui.

The passages of Velius Longus (13.7 = GL 8.4.1–3) and Marius Victorinus (4.31–32 = GL 6.13.11–12) quoted on pp. 166–7 suggest that the spelling quoi, and its genitive equivalent quoius, was also old-fashioned for these writers. We find no examples of quoi in the corpora, but the strange spelling cuoì, [c]ụ[o]i (TPSulp. 48) in the parts of a tablet written by the scribe presumably reflects a sort of compromise between quoi and cui (the non-scribal writer spells the word cuì). I know of no other examples of this spelling in Latin epigraphy.

Another conceivable instance of an old-fashioned spelling involving <o> are fornus (O. BuNjem 7), for[num (49), fornarius (8, 25), foṛ[narius] (10) for furnus, furnārius. The sequence /ur/ < *or or *r̥ in the standard forms of these words is unexpected; a dialectal sound change or borrowing from other languages is often supposed (I have argued for the latter: Reference ZairZair 2017). So these words could represent the original, older form, which is attested in manuscripts of Varro and by writers on language (Reference ZairZair 2017: 259). However, influence from fornāx ‘furnace, oven’ is also possible (thus Reference AdamsAdams 1994: 104);Footnote 9 another possibility is that /u/ was lowered by the following /r/ in syllable coda, which by this time was ‘dark’ in Latin (Reference Sen and ZairSen and Zair 2022). This might be particularly likely if there was some confusion of /ɔː/ and /u/ at Bu Njem.Footnote 10

The diphthong /ɔu/ became /oː/ and then /uː/ by the third century BC (see pp. 39–40). On the use of <o> in place of <u> in poplicos > pūblicus and words derived from it, see Chapter 17. It is possible that iodicauerunt (Kropp 11.1.1/26) in a curse tablet from Carthage, in the second century AD, for iūdicāuē̆runt < *i̯oudik- is an old-fashioned spelling representing the mid-point of the change (at any rate, no other explanation springs to mind). Since we have long /uː/ in the first syllable, this spelling cannot be explained by confusion of /ɔː/ and /u/. At least in legal texts, derivatives of iūs were particularly favoured for this (Reference DecorteDecorte 2015: 160–2), although use of <o> for /uː/ rather than <ou> was never common, even in the archaic period.

There are two environments in which spelling with <u> and <i> alternated in Latin orthography, with, on the whole, a movement from <u> to <i>, although in certain phonetic, morphological or lexical contexts the change in spelling either did not take place at all or took place at different rates. These environments are (1) original /u/ in initial syllables between /l/ and a labial; (2) vowels subject to weakening in non-initial open syllables before a labial. Both the question of the history and development of the spelling with <u> and <i>, and what sound exactly was represented by these letters is lengthy and tangled (especially with regard to the medial context; for recent discussion and further bibliography, see Suárez-Martínez 2006 and Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 584).

/u/ and /i/ in Initial Syllables after /l/ and before a Labial

In initial syllables we know on etymological grounds that the words in question had inherited /u/. In practice, there are very few Latin words which fulfil this context, and only two in which the variation is actually attested: basically just clupeus ~ clipeus ‘shield’ and lubet ~ libet ‘it is pleasing’ and its derivatives such as lubēns ~ libēns ‘willing’ (which is part of a dedicatory formula and makes up the majority of attestations of this verb), *lubitīna ~ libitīna ‘means for burial; funeral couch’, Lubitīna, Lubentīna ~ Libitīna ‘goddess of funerals’. No forms with <u> are found in liber ‘the inner bark of a tree; book’ < *lubh-ro-, whose earliest attestation is libreis in CIL 12.593 (45 BC, EDR165681), as well as being attested in literary texts from Plautus onwards. Strangely, lupus ‘wolf’ does not become ×lipus, as Reference LeumannLeumann (1977: 89) points out, although as it is attested in Plautus it was surely borrowed from a Sabellic language (as demonstrated by /p/ < *kw) early enough to have been affected.

As we shall see, both spellings are attested from the third century BC onwards in lub- and clupeus, with <u> predominating initially and slowly being replaced by <i>. Some scholars view this as a sound change from /u/ to /i/ (e.g. Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 153), others as the development of an allophone of /u/ to some sound such as [y], leading to variation in spelling with <u> and <i>, but with <i> eventually becoming standard (e.g. Meiser 1988: 80; making it more or less parallel with the development in non-initial syllables, which we shall discuss later).

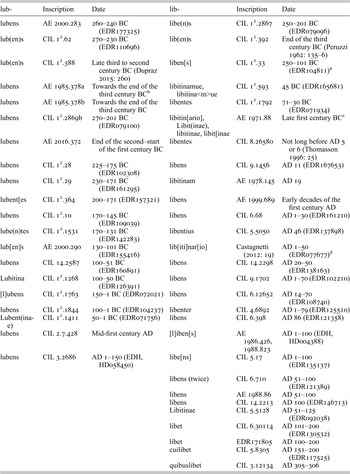

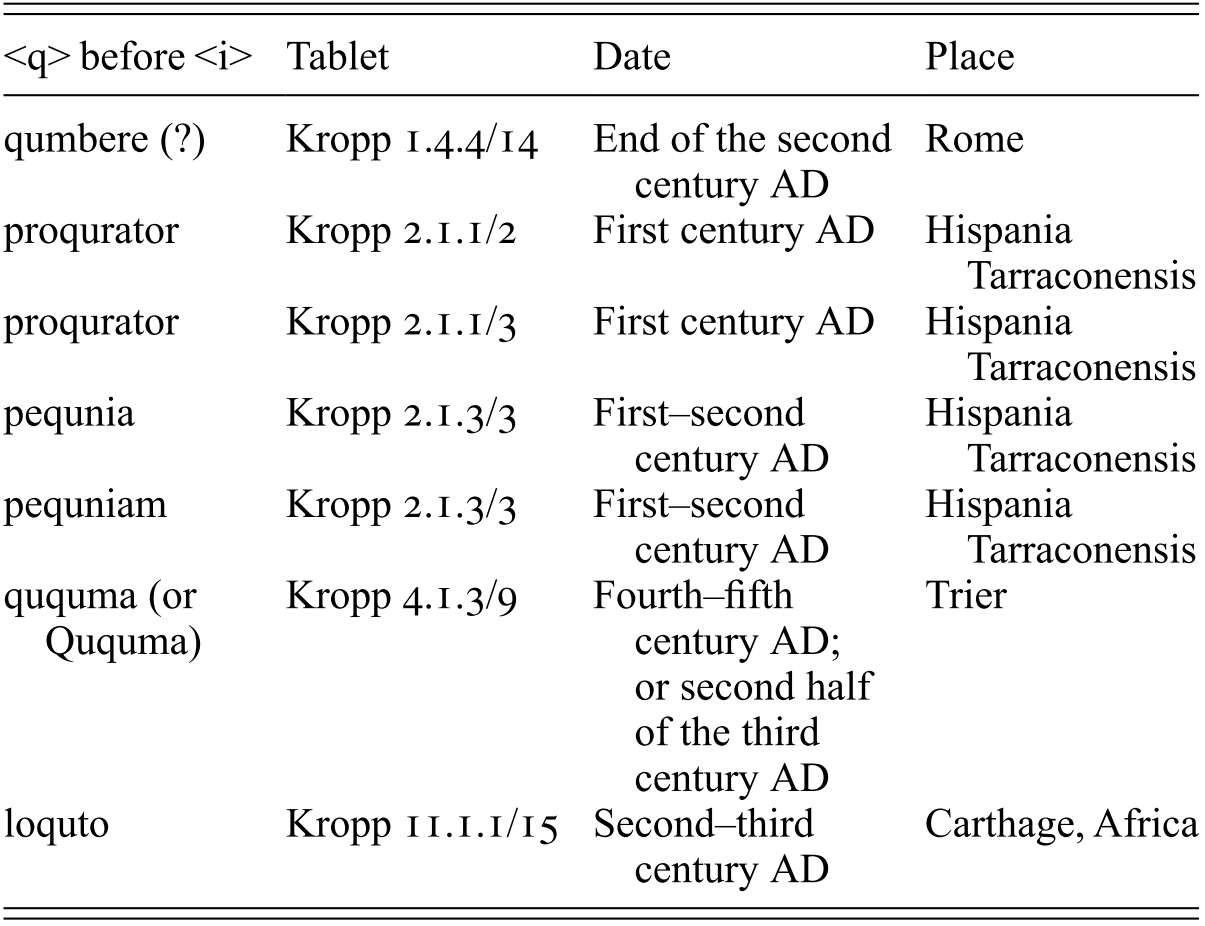

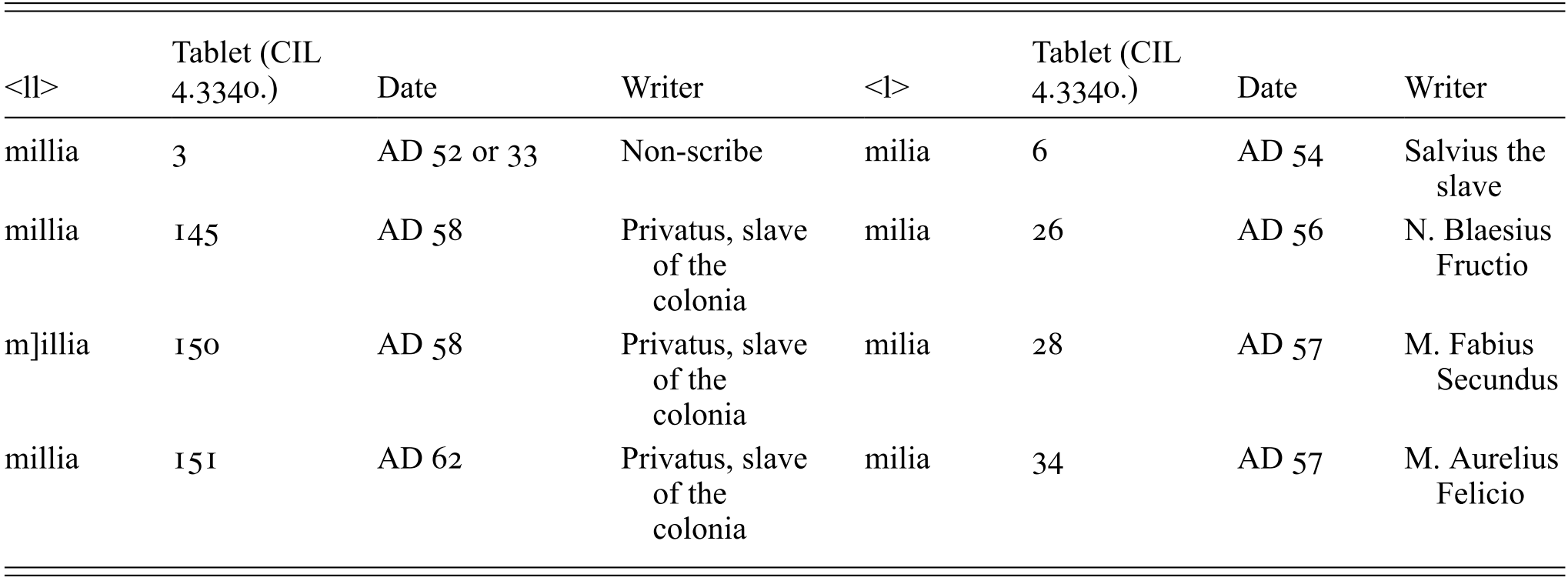

In epigraphy other than my corpora, the <i> spelling is attested early in the lub- words (see Table 3): libes (CIL 12.2867) for libēns is about the same time as the first instances of lubēns, but <u> outnumbers <i> by 13 (or 14, if CIL 12.1763 is to be dated early) to 3 in the third and second centuries BC. In the first century BC, however, there are only 4 (or 5 if CIL 12.1763 is to be dated later) instances of <u> to 4 of <i>, and subsequently <u>, with 2 instances in the first century AD (or 1 in the first, 1 in the second if CIL 3.2686 is to be dated late), is completely swamped: there are 16 (or 17 if CIL 5.5128 is to be dated early) instances of <i> in the first century AD, and in subsequent centuries the numbers are too massive to be included in the table.Footnote 1 These have not been thoroughly checked, and some are mere restorations, but the vast majority do indeed belong to the lexeme libēns.Footnote 2 Overall, then, it seems clear that the spelling with <i> was becoming more common in the course of the first century BC, becoming the usual spelling in the first century AD, and subsequently overwhelming the <u> spelling, although the latter is still occasionally found in the first, and perhaps second, century AD.

Table 3 lub- and lib- in inscriptions (omitting forms of libēns from AD 100)

| lub- | Inscription | Date | lib- | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lubens | AE 2000.283 | 260–240 BC (EDR177325) | libe(n)s | CIL 12.2867 | 250–201 BC (EDR079096) |

| lub(en)s | CIL 12.62 | 270–230 BC (EDR110696) | lib(en)s | CIL 12.392 | End of the third century BC (Reference PeruzziPeruzzi 1962: 135–6) |

| lub(en)s | CIL 12.388 | Late third to second century BC (Reference Dupraz, Dupraz and SowaDupraz 2015: 260) | liben[s] | CIL 12.33 | 250–101 BC (EDR104811)Footnote a |

| lubens | AE 1985.378a | Towards the end of the third century BCFootnote b | libitinamue, libitina<m>ue | CIL 12.593 | 45 BC (EDR165681) |

| lubens | AE 1985.378b | Towards the end of the third century BC | libentes | CIL 12.1792 | 71–30 BC (EDR071934) |

| lubens | CIL 12.2869b | 270–201 BC (EDR079100) | libitin[ario], Libit(inae), libitinae, libit[inae | AE 1971.88 | Late first century BCFootnote c |

| lubens | AE 2016.372 | End of the second–start of the first century BC | libentes | CIL 8.26580 | Not long before AD 5 or 6 (Reference ThomassonThomasson 1996: 25) |

| lubens | CIL 12.28 | 225–175 BC (EDR102308) | libens | CIL 9.1456 | AD 11 (EDR167653) |

| lubens | CIL 12.29 | 230–171 BC (EDR161295) | libitinam | AE 1978.145 | AD 19 |

| lubent[es | CIL 12.364 | 200–171 (EDR157321) | libens | AE 1999.689 | Early decades of the first century AD |

| lubens | CIL 12.10 | 170–145 BC (EDR109039) | libens | CIL 6.68 | AD 1–30 (EDR161210) |

| lube(n)tes | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | libentius | CIL 5.5050 | AD 46 (EDR137898) |

| lub[en]s | AE 2000.290 | 130–101 BC (EDR155416) | lib[iti]nar[io] | Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti (2012: 19) | AD 1–50 (EDR077677)Footnote d |

| lubens | CIL 14.2587 | 100–51 BC (EDR160891) | libens | CIL 14.2298 | AD 20–50 (EDR138163) |

| Lubitina | CIL 12.1268 | 100–50 BC (EDR126391) | libens | CIL 9.1702 | AD 1–70 (EDR102210) |

| [l]ubens | CIL 12.1763 | 150–1 BC (EDR072021) | libens | CIL 6.12652 | AD 14–70 (EDR108740) |

| lubens | CIL 12.1844 | 100–1 BC (EDR104237) | libenter | CIL 4.6892 | AD 1–79 (EDR125510) |

| Lubent(inae) | CIL 12.1411 | 50–1 BC (EDR071756) | libens | CIL 6.398 | AD 86 (EDR121358) |

| lubens | CIL 2.7.428 | Mid-first century AD | [l]iben[s] | AE 1986.426, 1988.823 | AD 1–100 (EDH, HD004388) |

| lubens | CIL 3.2686 | AD 1–150 (EDH, HD058450) | libe[ns] | CIL 5.17 | AD 1–100 (EDR135137) |

| libens (twice) | CIL 6.710 | AD 51–100 (EDR121389) | |||

| libens | AE 1988.86 | AD 51–100 | |||

| libens | CIL 14.2213 | AD 100 (EDR146713) | |||

| Libitinae | CIL 5.5128 | AD 51–125 (EDR092038) | |||

| libet | CIL 6.30114 | AD 101–200 (EDR130532) | |||

| libet | EDR171805 | AD 100–200 | |||

| cuilibet | CIL 5.8305 | AD 151–200 (EDR117525) | |||

| quibuslibet | CIL 3.12134 | AD 305–306 |

a Second century BC according to Grandinetti in Reference RomualdiRomualdi (2009: 150).

b But 170–100 BC on the basis of the palaeography according to EDR (EDR079779).

c Reference Hinard and DumontHinard and Dumont (2003: 29–35, 38, 49–51), on the basis of the spelling, language and historical context; similarly Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti (2012: 37–43).

d Not before the Augustan period, and prior to the change by Cumae from a municipium to a colonia in the second half of the first century, probably under Domitian (Reference CastagnettiCastagnetti 2012: 46–8).

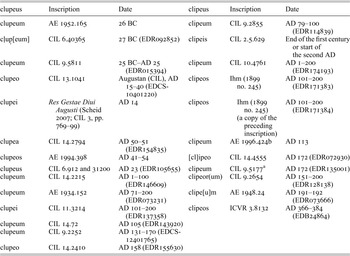

The spelling of clupeus ~ clipeus (Table 4) has a rather different profile: the lexeme is not found before the first century BC, when only the <u> spelling appears (2 or possibly 3 examples); in the first century AD there are 6–8 inscriptions which use <u>, but only 1–3 with <i> (and possibly quite late in the century), and still 4–5 <u> in the second century AD to 7 of <i>, with 1 <i> in the fourth.Footnote 3 It is perhaps surprising, given the common formulaic usage of lubens in dedicatory contexts, that clupeus appears to have retained the <u> spelling longer. Perhaps this is connected to the influence of the Res Gestae of Augustus.

Table 4 clupeus and clipeus

| clupeus | Inscription | Date | clipeus | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| clupeum | AE 1952.165 | 26 BC | clipeum | CIL 9.2855 | AD 79–100 (EDR114839) |

| cḷup̣[eum] | CIL 6.40365 | 27 BC (EDR092852) | clipeis | CIL 2.5.629 | End of the first century or start of the second AD |

| clupeum | CIL 9.5811 | 25 BC–AD 25 (EDR015394) | clipeum | CIL 10.4761 | AD 1–200 (EDR174193) |

| clupeo | CIL 13.1041 | Augustan (CIL), AD 15–40 (EDCS-10401220) | clipeos | Reference IhmIhm (1899 no. 245) | AD 101–200 (EDR171383) |

| clupei | Res Gestae Diui Augusti (Reference ScheidScheid 2007; CIL 3, pp.769–99) | AD 14 | clipeos |

| AD 101–200 (EDR171384) |

| clupea | CIL 14.2794 | AD 50–51 (EDR154835) | clipeum | AE 1996.424b | AD 113 |

| clupeos | AE 1994.398 | AD 41–54 | [cl]ipeo | CIL 14.4555 | AD 172 (EDR072930) |

| clupeus | CIL 6.912 and 31200 | AD 23 (EDR105655) | clipeum | CIL 9.5177Footnote a | AD 172 (EDR135001) |

| clupeum | CIL 14.2215 | AD 1–100 (EDR146609) | clipeor(um) | CIL 9.2654 | AD 151–200 (EDR128138) |

| clupeum | AE 1934.152 | AD 71–200 (EDR073231) | clipe[u]m | AE 1948.24 | AD 191–192 (EDR073666) |

| clupei | CIL 11.3214 | AD 101–200 (EDR137358) | clipeos | ICVR 3.8132 | AD 366–384 (EDB24864) |

| clupeum | CIL 14.72 | AD 105 (EDR143920) | |||

| clupeum | CIL 9.2252 | AD 131–170 (EDCS-12401765) | |||

| clupeo | CIL 14.2410 | AD 158 (EDR155630) |

a CIL in fact gives the reading clupeum, but clipeum is correctly given by EDR135001 (a photo of the inscription can be found under the entry).

Unsurprisingly, given the restricted number of lexemes containing the requisite phonological environment, there are very few instances of this type of <u> spelling in the corpora. However, lubēns ~ libēns is used occasionally in letters at Vindolanda, where <i> outnumbers <u> 5 to 1. The sole use of <u>, in lụḅẹṇṭịṣsime (Tab. Vindol. 260), occurs in a letter whose author Justinus is probably a fellow prefect of Cerialis, and which the editors suggest may be written in his own hand, as it does not change for the final greeting. Towards the end of the first century AD, it seems fair to call this an old-fashioned spelling.

The examples of <i> are libenter (291, scribal portion of a letter from Severa), libenti (320, a scribe who also writes omịṣẹṛas, without old-fashioned <ss>), libente[r (340), libentissime (629; probably written by a scribe)Footnote 4 and ḷibent (640, whose author and recipient are probably civilians, and which also uses the possibly old-fashioned spelling ụbe).

The <u> spelling also occurs in a single instance in the Isola Sacra inscriptions (lubens, IS 223, towards the end of the reign of Hadrian or later). There is a good chance that this is the latest attested instance of the <u> spelling.The inscription is partly in hexameters, the spelling is entirely standard, and <k> is used not only in the place name Karthago but also in karina ‘ship’. Again, it is reasonable to assume that the <u> spelling in this word might be considered old-fashioned.

/u/ and /i/ in Medial Syllables before a Labial

The second context for <u> ~ <i> interchange is short vowels which were originally subject to vowel weakening before a labial. Hence we are not dealing only with original /u/ as is the case in initial syllables, and hence the subsequent development is not necessarily the same as in initial syllables.

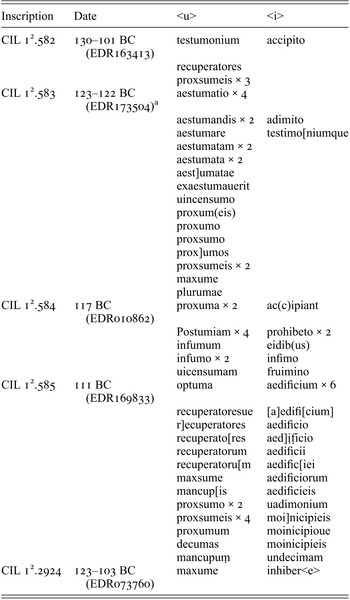

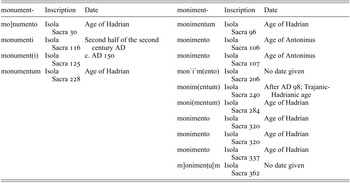

In order to utilise the evidence of the corpora it is necessary to first examine the highly complex evidence both of inscriptions and of the grammatical tradition, which descriptions in the literature such as Reference MeiserMeiser (1998: 68), Suárez-Martínez (2006) and Reference WeissWeiss (2020: 72, 128) tend to oversimplify.Footnote 5 Reference LeumannLeumann (1977: 87–90) provides a more comprehensive discussion. I will begin with the evidence of inscriptions down to the first century AD. In the first place, it is important to make a distinction which most of those writing about the <u> and <i> spellings do not make clearly enough. There are certain words in which the vowel before the labial was always written with <i> or <u> (as far as we can tell); presumably in these words the vowel had become identified with the phonemes /i/ or /u/ early on.Footnote 6 By comparison, there are some words in which the vowel before the labial shows variation in its spelling. The first instance of <i> before a labial is often attributed to infimo (CIL 12.584) in 117 BC (thus Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 19; Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 72), or testimo[niumque (CIL 12.583) in 123–122 BC (thus Reference Suárez-MartínezSuárez-Martínez 2016: 232). However, these are in fact the earliest examples of <i> in a word in which <i> and <u> variation is found. Probably earlier examples of the <i> spelling actually occur in opiparum ‘rich, sumptuous’ in CIL 12.364 (200–171 BC, EDR157321) and recipit ‘receives’ in CIL 12.10 (170–145 BC, EDR109039), for which a <u> spelling is never found.

In Table 5 I provide all examples of the use of <u> and <i> in this environment in some long official/legal texts of the late second century BC.Footnote 7 As can be seen, both spellings are found in these texts, but the distribution is not random. Most of the words with an <i> spelling never appear with a <u> spelling in all of Latin epigraphy: compound verbs in -cipiō,Footnote 8 -hibeō, -imō,Footnote 9 and forms of aedificium and aedificō,Footnote 10 uadimonium and municipium. Outside these particular texts, the same is true of pauimentum (CIL 12.694, 150–101 BC, EDR156830), animo (CIL 12.632, 125–100 BC, EDR104303). It looks as though by the (late) second century certain lexical items had already generalised a spelling with <i>.Footnote 11

Table 5 <u> and <i> in some second century BC inscriptions

| Inscription | Date | <u> | <i> |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIL 12.582 | 130–101 BC (EDR163413) | testumonium | accipito |

| recuperatores | |||

| proxsumeis × 3 | |||

| CIL 12.583 | 123–122 BC (EDR173504)Footnote a | aestumatio × 4 | |

| aestumandis × 2 | adimito | ||

| aestumare | testimo[niumque | ||

| aestumatam × 2 | |||

| aestumata × 2 | |||

| aest]umatae | |||

| exaestumauerit | |||

| uincensumo | |||

| proxum(eis) | |||

| proxumo | |||

| proxsumo | |||

| prox]umos | |||

| proxsumeis × 2 | |||

| maxume | |||

| plurumae | |||

| CIL 12.584 | 117 BC (EDR010862) | proxuma × 2 | ac(c)ipiant |

| Postumiam × 4 | prohibeto × 2 | ||

| infumum | eidib(us) | ||

| infumo × 2 | infimo | ||

| uicensumam | fruimino | ||

| CIL 12.585 | 111 BC (EDR169833) | optuma | aedificium × 6 |

| recuperatoresue | [a]edifi[cium] | ||

| r]ecuperatores | aedificio | ||

| recuperato[res | aed]ịf̣icio | ||

| recuperatorum | aedificii | ||

| recuperatoru[m | aedific[iei | ||

| maxsume | aedificiorum | ||

| mancup[is | aedificieis | ||

| proxsumo × 2 | uadimonium | ||

| proxsumeis × 4 | moi]nicipieis | ||

| proxumum | moinicipioue | ||

| decumas | moinicipieis | ||

| mancupuṃ | undecimam | ||

| CIL 12.2924 | 123–103 BC (EDR073760) | maxume | inhiber<e> |

a In fact EDR mistakenly gives the date as 123–112 BC.

By comparison, <u> spellings are found only in words which either show variation with <i> in the later period or which are subsequently always spelt with <i>,Footnote 12 such as testimonium, which across all of Roman epigraphy is found with the <u> spelling only in CIL 12.582.Footnote 13 The <u> spellings predominate in these words in these inscriptions: with <i> we have only infimo beside the far more common superlatives in <u>, the ordinal undecimam beside uicensumam, testimo[niumque beside testumonium, and eidib(us), which, as a u-stem, is also found spelt elsewhere with <u>.Footnote 14

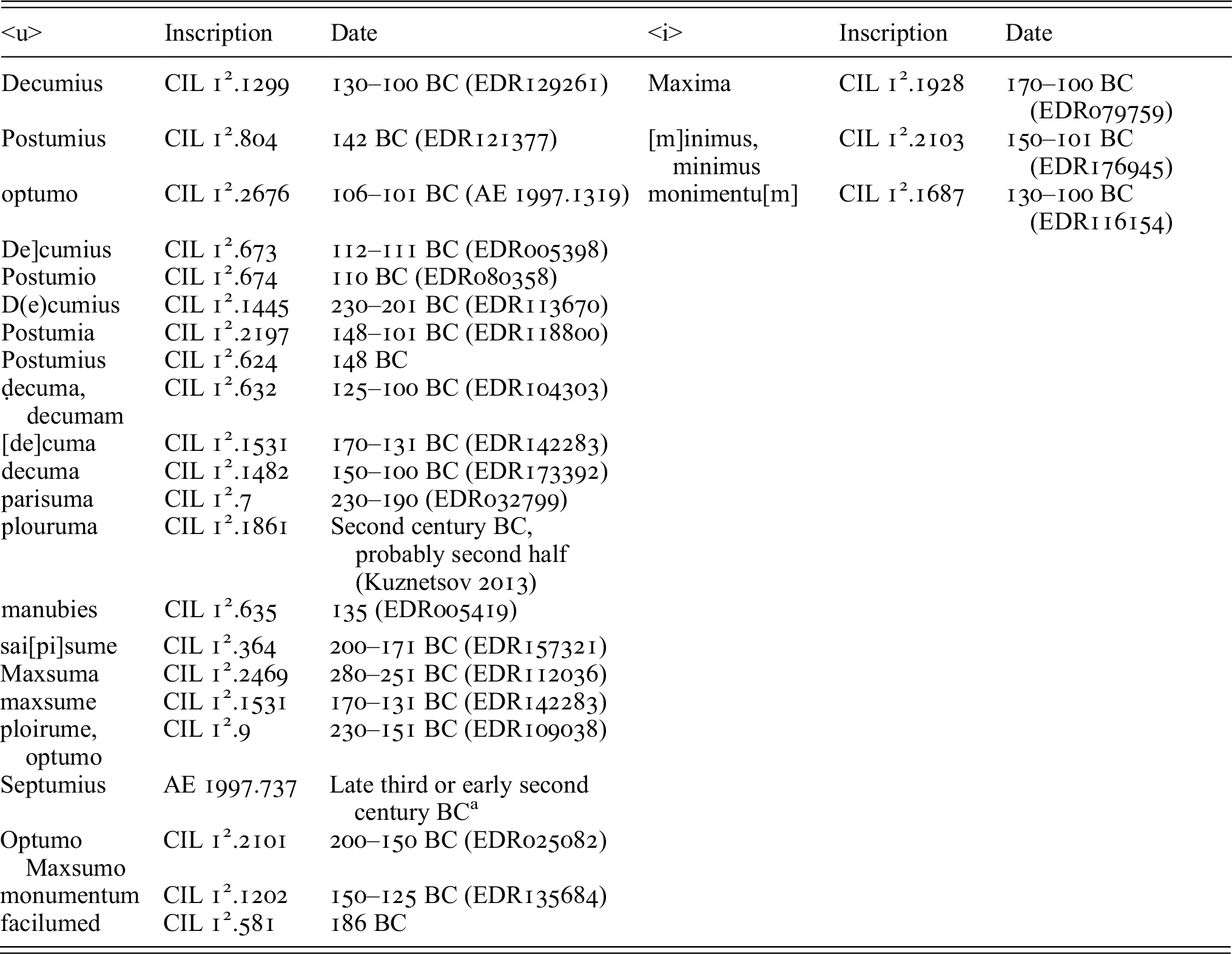

The same pattern is found in other inscriptions from the third and second centuries: in Table 6 I have collected all instances that I could find of <u> spellings in inscriptions given a date in EDCS, along with examples of <i> spellings of those words (other than those from CIL 12.582, 583, 584 and 585 and 2924). It seems clear that at this period the <u> spellings are dominant, although we do find a few <i> spellings (perhaps more towards the end of the second century). Nonetheless, all of these words do subsequently show <i> spellings (although the extent to which the <i> spelling is standard varies, as we shall see).

Table 6 Words with <u> spellings in the third and second centuries BC

| <u> | Inscription | Date | <i> | Inscription | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decumius | CIL 12.1299 | 130–100 BC (EDR129261) | Maxima | CIL 12.1928 | 170–100 BC (EDR079759) |

| Postumius | CIL 12.804 | 142 BC (EDR121377) | [m]inimus, minimus | CIL 12.2103 | 150–101 BC (EDR176945) |

| optumo | CIL 12.2676 | 106–101 BC (AE 1997.1319) | monimentu[m] | CIL 12.1687 | 130–100 BC (EDR116154) |

| De]cumius | CIL 12.673 | 112–111 BC (EDR005398) | |||

| Postumio | CIL 12.674 | 110 BC (EDR080358) | |||

| D(e)cumius | CIL 12.1445 | 230–201 BC (EDR113670) | |||

| Postumia | CIL 12.2197 | 148–101 BC (EDR118800) | |||

| Postumius | CIL 12.624 | 148 BC | |||

| ḍecuma, decumam | CIL 12.632 | 125–100 BC (EDR104303) | |||

| [de]cuma | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | |||

| decuma | CIL 12.1482 | 150–100 BC (EDR173392) | |||

| parisuma | CIL 12.7 | 230–190 (EDR032799) | |||

| plouruma | CIL 12.1861 | Second century BC, probably second half (Reference KuznetsovKuznetsov 2013) | |||

| manubies | CIL 12.635 | 135 (EDR005419) | |||

| sai[pi]sume | CIL 12.364 | 200–171 BC (EDR157321) | |||

| Maxsuma | CIL 12.2469 | 280–251 BC (EDR112036) | |||

| maxsume | CIL 12.1531 | 170–131 BC (EDR142283) | |||

| ploirume, optumo | CIL 12.9 | 230–151 BC (EDR109038) | |||

| Septumius | AE 1997.737 | Late third or early second century BCFootnote a | |||

| Optumo Maxsumo | CIL 12.2101 | 200–150 BC (EDR025082) | |||

| monumentum | CIL 12.1202 | 150–125 BC (EDR135684) | |||

| facilumed | CIL 12.581 | 186 BC |

a Dated to the second century AD by Kropp (1.11.1/1), presumably by mistake.

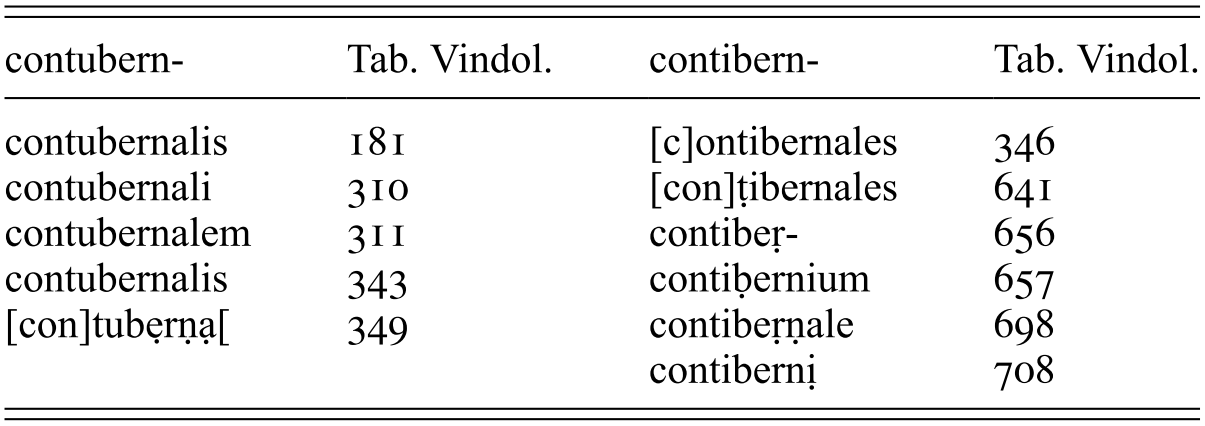

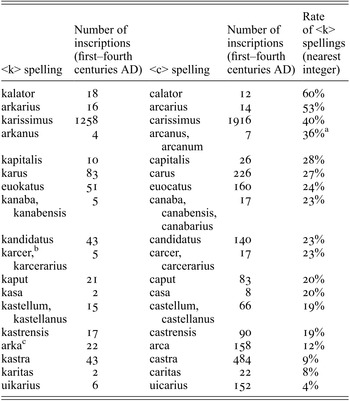

Overall, the picture seems to be a much more complex one than simply a move from early <u> spellings to later <i> spellings.Footnote 15 Although <u> spellings outnumber <i> spellings in some words and morphological categories in the second century BC, certain words have already developed a fixed <i> spelling by this period, with no evidence to suggest that they were ever spelt with <u>. Most other words will go on to see <i> supplant <u> as the standard spelling, although at varying rates as we shall see, but some, like monumentum, postumus and contubernalis, will strongly maintain the <u> spelling.

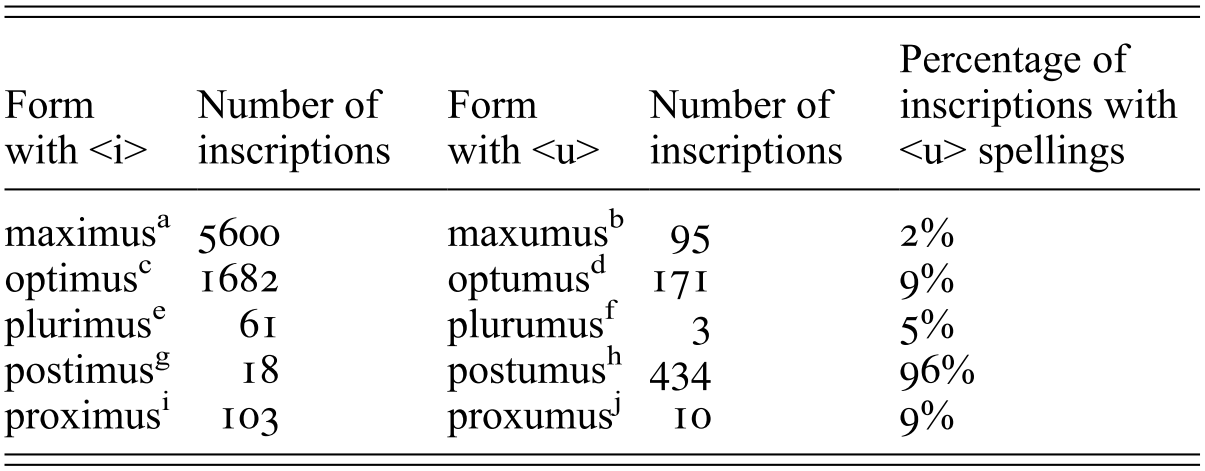

For the later period, Reference NikitinaNikitina (2015: 10–48) examines the use of <u> and <i> in words which show variation in a corpus of legal texts and ‘official’ inscriptions from the first centuries BC and AD. In the legal texts, she finds only <u> down to about the mid-first century BC, after which <i> appears: in a few texts only <i> is attested, but many show both <u> and <i>. The lexeme proximus seems to be particularly likely to be spelt with <u>, perhaps due to its membership of the formulaic phrase (in) diebus proxumis. Even in AD 20, the two partial copies of the SC de Cn. Pisone patri (Reference Eck, Caballos and Fernández GómezEck et al. 1996) contain between them 24 separate <u> spellings and 2 <i> spellings, while CIL 2.1963, from AD 82–84, has 7 instances of <u> (5 in the lexeme proxumus), and none of <i>. There are only two ‘official’ inscriptions of the first century BC which contain words with <u> or <i> spellings, but in the other ‘official’ texts of the first century AD, <i> spellings are heavily favoured (73 examples in 25 inscriptions) over <u> spellings (8 examples across 4 inscriptions).

An interesting observation is that in the first century BC, superlatives in -issimus are often spelt with <u>. By comparison, in law texts of the first century AD, except in the SC de Cn Pisone patre, all 10 attested superlatives in -issimus have the <i> spelling, whereas the irregular forms like maximus, proximus, optimus etc. show variation. Although the switch between <u> and <i> in the -issimus superlatives is probably less abrupt than Nikitina perhaps implies,Footnote 16 it does seem likely that the <i> spelling became particularly common in this type of superlative around the Augustan period: as we shall see below, in imperial inscriptions <u> is used vanishingly seldom.

Nikitina’s study makes it clear that there was a movement from <u> spellings to <i> spellings in some words in high-register inscriptions over the course of the first century BC and first century AD. This movement probably took place more slowly in the more conservative legal texts,Footnote 17 and more quickly in certain lexical items (notably superlatives in -issimus) than in others.

If we turn to the evidence of the writers on language, the question of the spelling of these words was clearly one of great interest for some time.Footnote 18 Quintilian briefly mentions sounds for which no letter is available in the Latin alphabet, including the following comment:

medius est quidam u et i litterae sonus (non enim sic “optimum” dicimus ut “opimum”) …

There is a certain middle sound between the letter u and the letter i (for we do not say optĭmus as we say opīmus) …Footnote 19

This appears to imply that the vowel in this context was not the same as either of the sounds usually represented by <i> or <u>.Footnote 20 The spelling with <u> was however apparently ‘old-fashioned’ for Quintilian (at least in the words optimus and maximus):

iam “optimus” “maximus” ut mediam i litteram, quae veteribus u fuerat, acciperent, C. primum Caesaris in scriptione traditur factum.

C. Caesar is said in his writing to have first made optimus, maximus take i as their middle letter, as they now do, which had u among the ancients.

Cornutus (as preserved by Cassiodorus) appears also to think that the <u> is old-fashioned, and suggests that the spelling with <i> also more accurately reflects the sound. He gives as examples lacrima and maximus, as well as ‘other words like these’:

“‘lacrumae’ an ‘lacrimae’, ‘maxumus’ an ‘maximus’, et siqua similia sunt, quomodo scribi debent?” quaesitum est. Terentius Varro tradidit Caesarem per i eiusmodi uerba solitum esse enuntiare et scribere: inde propter auctoritatem tanti uiri consuetudinem factam. sed ego in antiquiorum multo libris, quam Gaius Caesar est, per u pleraque scripta inuenio, <ut> ‘optumus’, ‘intumus’, ‘pulcherrumus’, ‘lubido’, ‘dicundum’, ‘faciundum’, ‘maxume’, ‘monumentum’, ‘contumelia’, ‘minume’. melius tamen est ad enuntiandum et ad scribendum i litteram pro u ponere, in quod iam consuetudo inclinat.

“How should one write lacrumae or lacrimae, maximus or maximus, and other words like these?”, one asks. Terentius Varro claimed that Caesar used to both pronounce and write this type of word with i, and this became normal usage, following the authority of such a great man. What is more, I find many of these words written with u in books of writers much older than Gaius Caesar, as in optumus, intumus, pulcherrumus, lubido, dicundum, faciundum, maxume, monumentum, contumelia, minume.Footnote 21 However, it is better to both pronounce and write i rather than u, which is the way common usage is going now.

Velius Longus discusses the vowel in this context in several places. What he says about it provides an important caution against us assuming that the ancient writers on language thought, like us, that the words with <u> and <i> variation formed a single category for which a single rule was necessarily applicable. Instead, it seems likely that they looked at each word, or category of word, individually (an approach which accurately reflects usage, on the basis of the epigraphic evidence). Note that he also includes among his examples lubidō and clupeus (discussed above, pp. 75–82). The first passage which touches on this issue is a long and complex one:

‘i’ uero littera interdum exilis est, interdum pinguis, … ut iam in ambiguitatem cadat, utrum per ‘i’ quaedam debeant dici an per ‘u’, ut est ‘optumus’, ‘maxumus’. in quibus adnotandum antiquum sermonem plenioris soni fuisse et, ut ait Cicero, “rusticanum” atque illis fere placuisse per ‘u’ talia scribere et enuntia[ue]re. errauere autem grammatici qui putauerunt superlatiua <per> ‘u’ enuntiari. ut enim concedamus illis in ‘optimo’, in ‘maximo’, in ‘pulcherrimo’, in ‘iustissimo’, quid facient in his nominibus in quibus aeque manet eadem quaestio superlatione sublata, ‘manubiae’ an ‘manibiae’, ‘libido’ an ‘lubido’? nos uero, postquam exilitas sermonis delectare coepit, usque ‘i’ littera castigauimus illam pinguitudinem, non tamen ut plene ‘i’ litteram enuntiaremus. et concedamus talia nomina per ‘u’ scribere <iis> qui antiquorum uoluntates sequuntur, ne[c] tamen sic enuntient, quomodo scribunt.

The letter <i> is sometimes ‘slender’ and sometimes ‘full’, such that nowadays it is uncertain whether one ought to say certain words with i or u, as in optumus or maxumus. With regard to these words, it should be noted that the speech of the ancients had a fuller – and indeed rustic, as Cicero puts it – sound, and on the whole they liked to write and say u. But those grammarians who have thought that superlatives should be pronounced with u are wrong. Because, if we should concede to them with regard to optimus, maximus, pulcherrimus, and iustissimus, what will we do in words which are not superlatives, but in which the same question arises, such as manubiae or manibiae, libido or lubido? After we began to prize slenderness in speech, we went as far as to correct the fullness by using the letter <i>, but not so far as to give our pronunciation the full force of that letter. So let us permit those who want to follow the habits of the ancients in writing <u> to do so, but not to pronounce it how they write it.

My understanding of this passage is that Velius Longus is saying that the pronunciation of the words he discusses involves a sound which is not the same as the sound represented by <i> in other contexts, and is apparently ‘fuller’, but not as ‘full’ as it used to be, when <u> was a common spelling. Nowadays, the usual spelling is with <i>, but people who prefer to use the old-fashioned spelling <u> may do so. However, they should not extend this to actually pronouncing the sound as [u], because if they did, they would also by the same logic have to say [u] in words like manibiae and libidō. This final point is rather surprising. Does it suggest that by the early second century AD, the vowel of the first syllable of libidō had already developed to /i/, and hence a spelling pronunciation of [u] would sound wrong? Perhaps the same could be true of manibiae, if the development of the medial vowel before a labial was very sensitive to phonetic conditioning, such that here the pronunciation had again fallen together with /i/, unlike in the superlatives.

The following passage suggests that variation in both spelling and pronunciation still existed, with mancupium, aucupium and manubiae (again!) containing a sound which some produced in an old-fashioned ‘fuller’ manner and spelt with <u>, while others used a more modern and elegant ‘slender’ pronunciation, and wrote with <i>. Unlike in the previous passage, it is not explicitly stated here that the pronunciation of the relevant sound is different from /u/ and /i/.Footnote 22