Although public policy affects our everyday lives, it can engender controversy. From a young age, we learn when discussing issues that there are two sides of an argument—for and against. Yet, understanding the multiple perspectives behind a policy is far from simple. This article examines results from students engaged in debate panels enrolled in an upper-level, undergraduate political-science elective: public policy.

More specifically, this article attempts to answer this question: Can debate panels provide a mechanism for students to understand multiple perspectives to shape a public policy? To invite students to become more conversant about various public issues, I devised a series of debate panels around substantive public-policy issues (e.g., immigration and public lands) during the fall 2017 semester at a public university in a Western state. The results indicate how hands-on learning activities encourage students to move beyond two-sided arguments to understand the complexities of public-policy making and how listening to multiple perspectives can lead toward finding a common ground.

USING DEBATES IN THE CLASSROOM

Using debates in the classroom is not without criticism. For example, Tumposky (Reference Tumposky2004) suggested that using debates in the classroom can invoke dualism because it forces students to form yes or no opinions about a topic. In comparison, other research suggests that debate allows students to more thoroughly explore and define a topic examining multiple perspectives (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2007). Furthermore, debates serve as a mechanism for active learning—students can talk, listen, read, write, and reflect (Meyers and Jones Reference Meyers and Jones1993). This style of learning is important because too often the customary pedagogical approach adopted, as Trueb (2013, 137) described it, is that “students only learn[ing] to write for the academic setting.”

As a result, instructors have adopted a wider array of teaching approaches to engage students with applied-learning experiences (Bain Reference Bain2004; McKeachie and Svinicki Reference McKeachie and Svinicki2006). This type of learning is critical for our students to be prepared after graduation. This article argues that semester-long debate panels illustrate why hands-on classroom projects could better prepare our students to make public-policy decisions in the future. In particular, this classroom assignment allowed students to engage in deciphering political and scientific facts. Schultz (2017, 775) suggested that this is imperative because “Decisions crafted out of political myths and faulty or no evidence yield bad public policy, wasting taxpayer dollars and leading to failed or ineffective programs. Yet too much policy is created without real evidence.”

THE LOGISTICS

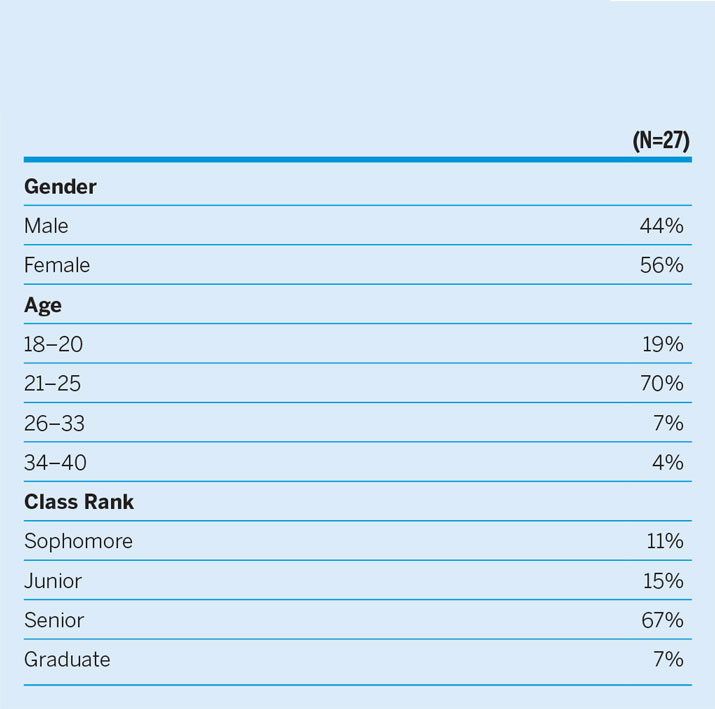

This article begins with an overview of course demographics and details about the debate panels before turning to findings. Thirty students enrolled in public policy, an upper-level undergraduate elective for a major in political science. Per university requirements, freshmen cannot register for an upper-level undergraduate political science course. Table 1 illustrates that the class had slightly more female than male students and that most students were between 21 and 25 years of age. The majority of students (67%) were seniors.

Also during the first week, students were asked to consider why we think about public policy in a bimodal manner—a guiding theme of the course—after reading Schultz’s (2017) “Alternative Facts and Public Affairs.”

Table 1 Overview of Demographic Data

During the first week of the semester, the class read chapters from Rinfret, Scheberle, and Pautz’s (Reference Rinfret, Scheberle and Pautz2018) Public Policy: A Concise Introduction to understand public-policy making and stages of the process. Also during the first week, students were asked to consider why we think about public policy in a bimodal manner—a guiding theme of the course—after reading Schultz’s (2017) “Alternative Facts and Public Affairs.” His article encourages readers to reflect on the differences between scientific and political facts. Schultz (2017, 776) argued, “For elected officials, what counts as facts and truth is what they learn from their constituents. A politician’s world is not controlled by experiments, hypotheses, and statistically valid samples; what counts as evidence in making policies are the stories and interests of voters.” For comparison, scientific facts are driven by a rigorous process of hypothesis testing, falsifying claims, and building on what is known from previous research (Schultz Reference Schultz2017).

Students used the university’s learning-management system, Moodle, to sign up for one debate panel. The debate-panel topics ranged from immigration, pay equity, public lands, jobs, student loans, guns, and energy to climate change. Each topic allowed four students to sign up; they broke into teams of two to present their side of the argument.

The class met two times per week for 1 hour and 20 minutes. Every Thursday, the class had a debate. The debate topic and a prompt were listed in the course schedule. For example, students who signed up to participate in the public-lands debate addressed the following question: Should the US Congress give states the authority to manage public lands? Side 1 of the argument (two students) investigated the transfer of federal lands to state control; side 2 (two students) articulated why the federal government should maintain oversight.

Debate Structure

In preparation for our weekly debates, designated class time was allocated during the second week of the semester. This provided an opportunity for debate teams to determine a research plan and arguments and to coordinate schedules to meet outside of class. Each Thursday, the class had a peer-reviewed article or book chapter pertaining to the debate topic to use as a guidepost. For example, during the debate panel about immigration policy, the entire class read chapter 8 (Civil Rights and Immigration Policy) in Rinfret, Scheberle, and Pautz’s 2018 textbook. In addition to this reading, debate panels were required to do outside research (i.e., at least four or five outside peer-reviewed articles per student) in order to write a four- to five-page outline of talking points (e.g., citing clear evidence for support) to demonstrate preparedness for this assignment.

When students were not debating, they were part of the audience; their entry into class was turning in one or two questions linked to the debate based on the core reading assignment for the day. These students were required to ask a question and explain why it was a good one. The questions were addressed during the debate question-and-answer segment.

The format for the debate forums was as follows: (1) one-minute opening statements; (2) 10 minutes for members of the debate team to present their side; (3) 15 minutes for audience questions to be answered; (4) each side asks the other side a question; and (5) a one-minute closing statement. At the end of each debate panel, the audience (i.e., non-debaters) was asked to vote on which side was more persuasive. The outcome of the vote did not impact the debate-panel’s grade. Each week, a student volunteer kept track of time using timecards to facilitate the debate panel. The instructor selected and posed questions to the debate panels to avoid any overlap.

Throughout the debate panels, the student audience was asked to write down facts or additional questions that came up during the debates. At the end of each class session, students were allotted time to use their smart device or computers to fact-check statements and consider what would be common ground for the topic at hand. The instructor led a discussion about their findings and asked the class for ideas on how policy makers could consider multiple perspectives. In particular, the class often deciphered whether debate panels presented information by using political facts or scientific facts (Schultz Reference Schultz2017). Scientific facts are defined as peer-reviewed research (e.g., journal articles, books, government reports, and public-opinion data). An example would be if a student stated, “The Environmental Protection Agency has found that 27% of transportation drives greenhouse emissions in the United States.” For comparison, political facts are used for electoral support. For example, if a student stated, “Fifty percent of the US population does not support immigration policy,” this statement does not indicate the question posed, sample size, or organization used to collect the data.

Academic Requirements

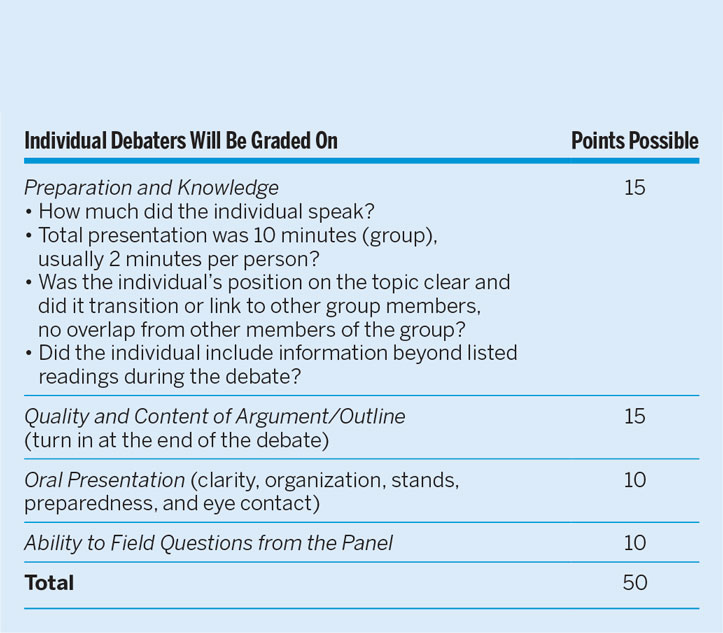

The debate panels were worth 110 of 485 points possible for the course (23%). A rubric was included in the course syllabus to evaluate debate panels (table 2). More specifically, although students were part of a team, each was graded individually on his or her ability to participate in the overall debate panel, answer questions, demonstrate their preparedness, and overall quality. Throughout the semester, students turned in debate questions six times for 10 points possible. These could be handwritten or typed but had to be turned in at the beginning of class, clearly asking a question linked to the readings for the day with evidence for support and explaining why this was a good question. Students were not allowed to turn in their questions late or during the debate panel.

Table 2 Debate-Panel Rubric

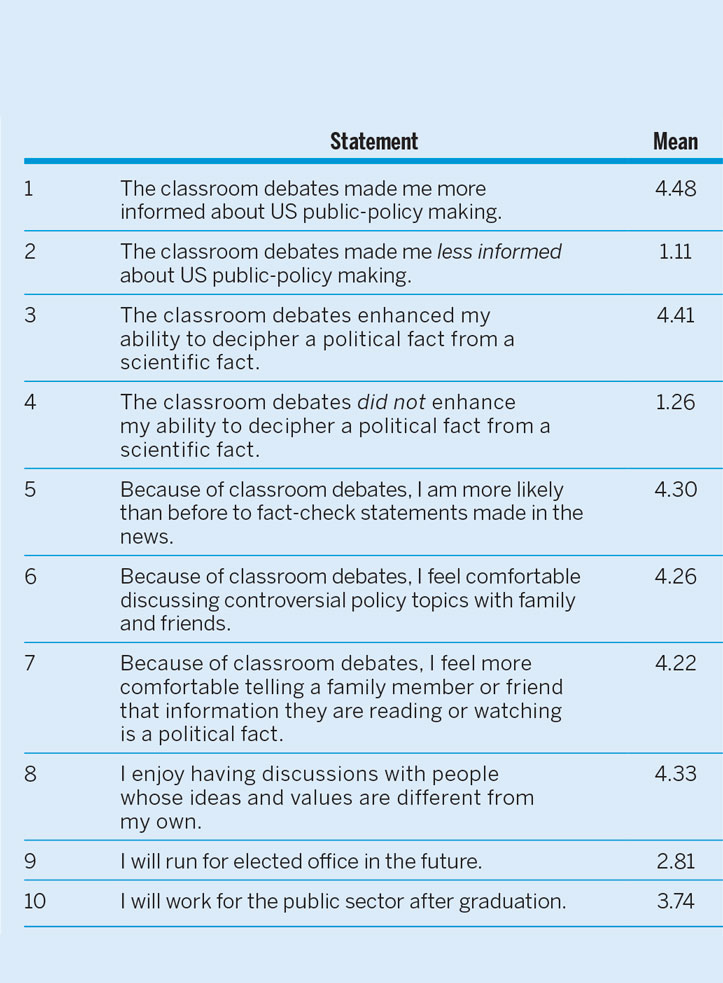

The broader implications or lessons learned in this course were evaluated using a survey (table 3) at the end of the semester to obtain student feedback. Students were asked to complete this survey during the final day of class using a scale of 1 to 5 (i.e., 1=strongly disagree and 5=strongly agree).

Table 3 Student Feedback Survey

At the end of each survey, students were asked the following open-ended question: After completing the debate forums, are you able to consider a middle ground when examining public-policy issues more broadly?

LESSONS LEARNED

Although the sample size was relatively small (i.e., N=27), important results can be gleaned from the students enrolled in this course. Table 4 reports the mean results from the end-of-semester survey using the scale 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. Students who participated in the survey agreed that the classroom debate panels made them more aware of US public-policy making and their ability to decipher political facts from scientific facts. Moreover, the debate panels increased their comfort level when discussing controversial public-policy topics with family and friends and with individuals who might have a different perspective. However, the debate forums left students neutral about whether they would work for the public sector after graduation, and most students disagreed that they would run for an elected office.

Of the 27 students, two clear themes emerged: the ability to actively listen to others and the capacity to find a common ground. More than half of the class (i.e., 15 of 27) stressed that the debate panels engendered their ability to actively listen to perspectives that were different from their own.

Table 4 Results

Note: N = 27.

The quantitative results indicate that student learning was enhanced through the debate panels. However, the question becomes whether this classroom activity was a mechanism to find ways for students to determine if a middle ground can be achieved surrounding controversial policy topics. The open-ended responses examine key themes.

Of the 27 students, two clear themes emerged: the ability to actively listen to others and the capacity to find a common ground. More than half of the class (i.e., 15 of 27) stressed that the debate panels engendered their ability to actively listen to perspectives that were different from their own. According to one student, “Normally I do not like to listen to other perspectives that are different from my own, but participating in the debate panels made me think I should be a better listener.” The ability to listen also allowed students to become more observant of how to decipher political facts from scientific facts. As one student noted, “Usually I just watch the news or debates and never think about how the information is used. Now I write down facts and research their source and how the information is being presented.” The debate panels allowed students to listen more carefully to various perspectives and to research information surrounding a topic and its origins.

The debate panels also allowed students to understand that evaluating public policy through a bimodal lens can be shortsighted. According to one student, “Far more effort can be made by legislators on both sides of the aisle to compromise by finding agreement and not seeing things in black or white lenses.” Another student shared this sentiment: “We need to value compromise, move beyond for or against, and craft stronger policy solutions to benefit more people.” These attitudes are contrary to Tumpoksy (2004), who suggested that debates within the classroom only engender additional dualism.

Although the majority of students reported the value in this learning experience, some drawbacks were apparent. Inevitably, working in groups or with partners can pose problems. One student group struggled due to the lack of preparedness by their classmate. Fortunately, being graded individually addressed some of these concerns.

Another complaint was the selection of topics for the debate panels. Many of the students did not find the discussion about manufacturing jobs to be intellectually stimulating. However, these complaints led to larger in-class discussions about how this mindset could be detrimental to policy decisions. As one student stated, “It is alarming that classmates find something dull because they haven’t experienced what it is like to grow up in a manufacturing household. Not everyone is going to get a high-tech job.”

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The debate panels served as an exploratory mechanism for instructors to create active-learning opportunities for students to value a multitude of public-policy perspectives. In the words of one student, “This class should be required for all majors across campus. If we cannot find a common ground on important decisions that affect our lives, our democracy is at stake.”

Although it can be difficult for many to see the viewpoints of others, our students and our classrooms remind us that it is achievable. The classroom functions as a vehicle for students to move beyond dualism and to understand that although public policy is inherently complex, we can use multiple perspectives to find solutions.