In nineteenth-century Iran, criminals were often subjected to highly ritualized punishments in which they were paraded, often on foot or by pack animal, before a town or city's general population. Known in Islamic jurisprudence as a publicizing punishment (tashhīr) and being paraded around town (shahr gardāndan) in Persian government sources, these punishments foregrounded humiliation, shame, and loss of honor. Unlike talionic punishments that operated on an eye-for-eye or life-for-life logic, such punitive parades did not reduce punishment to a logic of equivalences. Nor was their main objective the infliction of pain, as was the case with many other forms of corporal punishment. Strangely, punitive parades frequently involved the criminal being forced to parade bareheaded, with a shaved head or facial hair, or wearing a ridiculous hat. The purpose of this article is to understand the cultural meanings associated with shaved or shortened hair, the exposed head, and headgear in order to explain their use in punishments. At a semiotic level, the meanings of these punishments were both at odds but connected with the licit ritual meaning of the same act, especially those involving hair. Hair and hat punishments were, respectively, temporary forms of bodily mutilation akin to more permanent ones such as chopping ears, the nose, fingers, toes, hands, feet, and distortions of the body's public self-presentation, such as through branding.Footnote 1 Temporary and permanent punishments were communicative acts, signifying exposure, shame, and even bestialization.

This article draws on an array of primary sources, ranging from diaries, travelogues, police, consular, and government reports, and official newspapers to works of Islamic jurisprudence, reformist texts, local and official chronicles, petitions, and telegraphic reports and responses. It begins by examining the penal uses of shaving men's hair, especially in the case of beardless youths (amrads) and Jews, as a punishment for crimes associated with a host of licit activities around illicit sex, illegal entertainment music, and alcohol production. It then turns to the striking case of the penal shaving of women's hair, almost always done in cases involving illicit sex, whether adultery, prostitution, or procurement. Shaving women's hair was a way of removing a core element of their sexuality. If a woman's head hair was a marker of her femininity, a man's facial hair similarly signified his manhood. The forcible removal of men's facial hair therefore became a culturally extreme form of punitive exposure. Finally, the article ends by concentrating on the ubiquitous removal of headgear during punishments for major crimes and the less common, but no less shameful, forcible wearing of a silly hat. Since headgear embodied social status, punishments of this nature erased or debased the criminal's previous social personhood.

Reading Penal History through Hair and Headgear Studies

While most scholarship on hair and headgear in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has focused on the onset of modernity and changes in sartorial regimes, the question of veiling, gender and sexuality, and other cultural meanings associated with hair and the head in penal contexts have largely been ignored.Footnote 2 By contrast, recent scholarship on early and medieval Islamic history delves into the complex ritual and penal meanings associated with hair punishments.Footnote 3 Importantly, anthropological and sociological studies on hair have guided my thinking about ritual, the sacred, and social control, all three of which are at the heart of many nineteenth-century Iranian penal practices.Footnote 4 Edmund Leach's seminal essay, “Magical Hair,” draws on ethnographic accounts to make three broad generalizations about the relationship between hair and sexuality: long, uncut hair was a marker of unrestrained sexuality; cut or bound hair had to do with restricted sexuality; and a shaved head meant celibacy.Footnote 5 Moving away from a purely sexual focus, C. R. Hallpike argues that cutting off hair had much to do with social control.Footnote 6 As a result, those with long hair were considered social outcasts, such as witches, recluses, or women, whereas those with short or cut hair were associated with obedience and discipline, such as soldiers, monks, and convicts.Footnote 7 Employing binary constructions, sociologist Anthony Synnott views hair in terms of opposites: opposite ideologies have opposite hair, just as opposite sexes have opposite hair.Footnote 8

In light of this scholarship, I argue that hair and hat punishments in nineteenth-century Iran embodied elements of ritual, sexuality, social control, and marginalization (i.e., the opposite of being normal). Recipients of such punishments were usually paraded ritualistically through the streets; the shearing of the beautiful locks of a beardless youth, a woman, or a man's beard or head hair all had sexual components having to do with shame and honor; as visible markers of shame, hair and hat punishments likewise were meant to assert control, governmental or religious, over the condemned, which sometimes dovetailed with enforced differentiation between communities such as Jews and Muslims; and finally, the cutting of hair, being bareheaded, or the forcible wearing of silly headgear all signaled social abnormality, marginalization, and even bestialization.

Shaving Men's Hair

Hair was considered sacred in many societies, in the sense of being both holy and taboo. As such, prohibitions and regulations governing its growth, length, and cutting have historically existed. Mary Douglas stressed hair's dangerous, or “left sacred,” dimensions, as it is at the margins of the body.Footnote 9 Émile Durkheim emphasizes the sacred, ritualistic dimensions of hair cutting, including prohibitions on coming into contact with it.Footnote 10 E. P. Thompson highlights the ritualistic and punitive dimensions of hair punishments in parades, describing the mid-nineteenth-century Rebecca gangs in rural England who blackened the houses of men and women who breached morality laws and beat, paraded, flogged, and cut their hair off.Footnote 11

In Muslim societies, shaving one's hair was an act laden with ritual significance.Footnote 12 For instance, as part of a religious rite known as the ʿaqīqah, a child's forelock was shaved and its weight offered as alms.Footnote 13 The Quran prescribes that male pilgrims shave their heads upon concluding the Muslim pilgrimage (ḥajj).Footnote 14 In many other contexts, however, men were expected to have head hair, albeit of a certain length, just as they were expected to have facial hair.Footnote 15 This mode of thinking is reflected in the book of laws of the nineteenth-century Iranian prophet Mīrzā Ḥusayn Nurī Bahāʾullāh (Baha'u’llah). In it, he prohibited believers from shaving their head hair or allowing men's hair to grow longer than their earlobes.Footnote 16 Still, in nineteenth and early twentieth-century Iran, it was common practice for men to voluntarily shave all or part of their scalps as an act of piety. Others, including some ruffians (lūtīs), villagers, soldiers, and courtiers, also shaved parts of their scalp but allowed hair to grow from the sides and/or the back into locks of hair.Footnote 17 Outside the domestic sphere, however, men typically wore headgear that only allowed the side or back of their head to be visible, keeping the shaved scalp covered.

In many Muslim societies, historically, hairstyle was also a means of community differentiation; for non-Muslims, on the other hand, hairstyle could signify subordination. In certain prophetic sayings (ḥadīth), Muslims are advised to differentiate their hairstyles from those of Jews and Christians.Footnote 18 Drawing on early Arabic texts, Petra Sijpesteijn suggests that the forcible cutting of the forelock “symbolized submission to a disciplinary regime, social control, and obedience.”Footnote 19 The Quran, for instance, mentions grabbing or shearing the forelock as a humiliating practice.Footnote 20 The shearing of a forelock also signified the vanquishing of an enemy whose life was spared or that someone had a debt to repay.Footnote 21 Shades of these meanings are apparent in the regulations of non-Muslim (dhimmī) hairstyles. The Pact of ʿUmar, which included regulations regarding the appearance of non-Muslims, stipulated that these communities were forbidden from parting their hair in the manner of Muslims and were required to shear their forelocks.Footnote 22 In his dhimmī regulations, the jurist Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 1350) argued that non-Muslims had to shave the top fourth of their head hair, not just trim their locks. This more robust form of shaving would unambiguously communicate their status as dhimmī.Footnote 23 Similar rationales for shaving the front of the head of dhimmī populations are found in Shiʿi works of jurisprudence, including those from the nineteenth century.Footnote 24

The penal uses of shaving men's hair also appear in Islamic jurisprudence and public regulation (ḥisbah) manuals. Early Sunni hadith, works of jurisprudence, and ḥisbah manuals mention shaving the hair of someone who provides false witness testimony or engages in perjury (shahādat al-zūr) as a discretionary (taʿzīr) punishment.Footnote 25 Shiʿi jurists, on the other hand, considered this the appropriate punishment for three categories of crime: the unmarried male fornicator; the male pimp; and the male Jew making a false accusation of fornication (zinā) against a Muslim.Footnote 26 While the first two categories related to violations of sexual norms, the latter involved violating the sanctity of Islam through a speech act involving illicit sex, resembling the punishment for false witness testimony. Implied in these punishments is an understanding that temporarily disfiguring one's appearance was a suitable response to one's violation of sexual norms.

On rare occasions, a man who cut another man's locks may have done so as an act of heroic retribution. Sayyid Asadullāh, a shrine servant with a history of conflict with Naṣrullāh Khān, the former Assistant Governor (Nāʾib al-Ḥukūmah) of Kashan, decided to beat Naṣrullāh Khān up when he came to Qum and cut off his locks (zulfash ra mīburad). This and other misdeeds were reported by Qum's government to the shrine guardian (Mutivallībāshī), who only levied a minor punishment for the crime.Footnote 27

As with so many other penal practices, however, known cases––even carried out by Shiʿi mujtahids––often deviated from the letter of jurisprudence. Two categories of men seem to have recurrently been the object of hair cutting: Jewish musicians and beardless youth (amrads). In the former case, Shiʿi mujtahids and their followers carried out this punishment, which was sometimes referred to as a shari‘ah and/or mandatory fixed punishment (ḥadd), despite no mention of either in works of jurisprudence. Given the significance of hair as a marker of community distinction, it is possible the punishment was meant to reinforce both the difference and subjugation of Jewish subjects seen to have contravened Islamic public moral norms by performing for Muslims at underground parties. In the case of beardless youth, however, the shaving of locks appears to have had an altogether different function, one that more closely paralleled its use for women: it was meant not only to shame the condemned but also to remove a marker of their beauty and seductive potency.

Amrads and Sexual Criminals

Amrads often shaved their beards intentionally, once past a certain age, in order to retain a particular aesthetic deemed pleasing to men. While the amrad may have willingly shaved his facial hair in contravention of societal norms, he usually still had tresses (zulf), markers of beauty. It was, therefore, not uncommon for Qajar authorities to cut amrads’ tresses as punishment. In the spring of 1887, a male prostitute amrad was engaging in “evil deeds and disorder” (sharārat va harzigī) among the shop owners of Shiraz. The local government had already punished the young man several times, but he continued his illicit actions. The government thus ruled (ḥukm) that he should be beaten with a stick, have the locks of his hair shaved off, and be banished and exiled (nafy va ikhrāj) from the city.Footnote 28 In Hamadan, an amrad was caught drunk, yelling (ʿarbadah) in the streets, and sentenced by the prince-governor to his locks being shaved and being entrusted to the master baker (ustād khabbāz) with the goal of rehabilitating him through learning a licit trade.Footnote 29

In other cases, men's hair was cut for attempted sexual assault, suggesting a connection to sexual immorality but not necessarily one to reducing male beauty. Although Islamic jurisprudence called for shaving men's hair for male pimping and fornication, the punishment was rarely enforced. The use of it for sexual assault, however, was the closest practice came to theory. In Qum, a woman at the bazaar to buy bread found herself surrounded by ruffians (alvāt), who whisked her away against her will to a local ruin (kharābah). She started screaming and managed to free herself from their grip. The main culprit, Ṣādiq, was a repeat offender. The local Assistant Governor had his locks cut off (zulf-i ū rā tarāshīdah) and made him write a note promising to never again engage in such illegal actions. The other two ruffians, however, managed to escape.Footnote 30

Jews

The shaving of Jewish men's hair, a common occurrence in Shiraz, carried multiple meanings within hair regulations and punishments. At one level, such shaving did connote a subordination and differentiation, as seen in certain hadith and promoted by later jurists. On another level, Shiʿi jurists also cited shaving as a punishment for a Jew who falsely accuses a Muslim of zinā. In practice, however, many of the Jews punished in this manner were either musicians or involved in facilitating the consumption of alcohol by Muslims. Since both alcohol and music were associated with underground parties frequented by prostitutes, there may have been also a partly sexual rationale for this punishment. In Shiraz, unlike almost all other instances in which government authorities meted out this punishment, the mujtahid Sayyid ʿAlī Akbar Fālasīrī and his followers were at the forefront, often enacting the punishment against the wishes of local and central governments.

In the summer of 1881, Sayyid ʿAlī Akbar Fālasīrī encountered a Jewish man carrying a pitcher (ẓarf) of liquor (ʿaraq) to the house of a Muslim on a side street; as an act of summary punishment, he broke the man's pitcher and cut off his locks of hair (zulfhā). In response, Jews taped a broadsheet (kāghaz) to the mujtahid's house with the following message: “Why do you forbid us from selling wine? Ban your own mullahs who buy our alcohol. If you want to do such things in the future, we will kill you.” This message, dotted with several unmentioned curse words, sent Fālasīrī into a rage, leading him to call––from his pulpit at the Masjid-i Vakīl––for Jews to be killed after the month of Ramażān. Ḥājjī Amīr, the Amīr-i Dīvānkhānah (head of the central government judiciary) in Shiraz, went to speak to Fālasīrī: “What kind of ruling is this you have made? Is the killing of Jews in your hands? This is a government issue (īn kār-i dawlatī ast). Do you want to throw Fars and the country of Iran into disarray?” Ḥājjī Amīr's position was that only the Qajar government had the right to direct violence towards its subjects, not the ʿulamā. Fālasīrī fell momentarily silent, but then spelled out his logic: “Selling wine and playing music (muṭribī) must stop. They [the Jews] must shave their heads and refrain from wearing fine clothing (libās-i fākhir). If they do not do so, I will do what I must do.”Footnote 31

This episode is striking for a number of reasons. First, much like the hair-cutting punishment for prostitutes and amrads, it suggests a shaming function. Second, it is also indicative of a method to further visually differentiate Jewish men from Muslim men; a method made clear in Fālasīrī's later pronouncement that all Jews––not just those guilty of a particular crime––voluntarily shave their locks and not wear elegant clothing. Finally, the fact that this punishment was otherwise primarily associated with women or beardless youth suggests it was a form of emasculation.

All other known cases of Jewish men's hair being shaved related to musicians and dancers, unsurprising given the close association between alcohol, music, dance, and moral crimes. In June 1889, four Jewish musicians (muṭribs) played at someone's house at night. Fālasīrī sent a group (jamīʿatī) to raid the party and destroy all the musical instruments. The crowd detained the Jewish musicians and took them to Fālasīrī's home, where they were kept until morning and then “thoroughly punished” (tanbīh-i kāmil) and their locks shaved off.Footnote 32 In another similar event a year later, Fālasīrī had Jewish musicians brought to him and imprisoned, inflicting a ḥadd punishment and cutting their locks off in the morning. In response, the government sent a messenger to tell Fālasīrī that, without government involvement, such actions were not correct; he replied with a declaration to sacrifice himself on the path of shariʿah.Footnote 33 Several years later, Fālasīrī was still continuing to raid private parties. In 1892, for example, Fālasīrī sent several seminarians and a sayyid to a residence where Jewish musicians were performing. After the musicians were caught and brought to the mujtahid, they were punished extensively with both lashings and shaving their locks. The Bīglarbīgī (police magistrate) was informed of the situation, but instead of being upset with Fālasīrī for encroaching on police work, he had the neighborhood's day guard (pākār) bastinadoed and imprisoned for not informing him of the events.Footnote 34

The Bīglarbīgī's same hesitance to punish Fālasīrī and his supporters was also apparent in a case involving a Jewish musician and his dancing boy. Mullā Āqā was a famous Shirazi Jewish musician who employed a Jewish dancing boy of fourteen or fifteen years old. A shoe weaver (urusīdūz) invited the two to his house on two or three occasions, but they did not attend. One night, the shoe weaver spent quite a bit of money on a party and invited ten to twenty guests. Mullā Āqā attended but did not bring the dancing boy with him, which annoyed the shoe weaver. At a later date, the shoe weaver harassed Mullā Āqā and the dancing boy at another residence. When the two were on their way home eight hours into the night, the shoe weaver gathered fifteen people, all armed with clubs (yarāq), to attack them, attempting to abduct the dancing boy. Mullā Āqā fended them off temporarily, but suffered injuries to his head and forehead, and the crowd managed to abduct the dancing boy. Mullā Āqā informed the Bīglarbīgī that same night, and the latter dispatched his head attendant and several agents to investigate, but the investigation led nowhere. The next day, the dancing boy turned up at Fālasīrī's house. As Fālasīrī's son intended to shave the boy's locks, Mullā Āqā offered the son a present (taʿāruf) in exchange for the boy. This indicates that Mullā Āqā was mainly concerned by the punishment's removal of the boy's beauty and the associated financial consequences for his entertainment troupe. Meanwhile, the Bīglarbīgī intended to punish (tanbīh) the crowd that abducted the boy in the first place, but they responded that they had merely been carrying out the orders of Fālasīrī's son, who wanted the dancing boy's locks shaved. As in the previous case, the Bīglarbīgī did not want to take on Fālasīrī's network and let the matter slide.Footnote 35

The punitive cutting of men's hair involved shaming by emasculation, reinforcing subordination in the case of the Jews, and/or reducing male beauty in the case of amrads. When carried out in an extralegal fashion, these actions could also signify retribution and dominance. The use of the hair-cutting punishment in the case of male sexual assault on a woman came closest to that found in Islamic jurisprudence for fornication.

Shaving Women's Hair: Adultery, Prostitution, and Procurement

Men who voluntarily shaved their heads or beards have been written about quite extensively in Islamic history. This is less the case for women who cut their own hair, even though they are no less key to contextualizing the penal (and therefore forced) equivalent. Historically, women voluntary cutting their own hair held associations with mourning, although by the nineteenth century such actions had also taken on other meanings. ʿAlī Aṣghar Fīruznīā argued that women in Persian poetry and prose cut their hair as an act of mourning.Footnote 36 In the Shāhnāmah, Farangīs, the wife of the slain warrior Siyāvush, cuts her own hair to mourn the event.Footnote 37 In Persian mystic Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār's Taẕkirat al-Awliyā (Memorial of the Saints), a mother mourns her son's murder by cutting her hair in grief.Footnote 38 Surprisingly perhaps, female voluntary hair cutting did not have a sexual significance akin to cross-dressing. For instance, there are photos of Qajar-era prostitutes dressed like men, but whose long tresses were still visible even when their hairstyle was distinctly male.Footnote 39

By the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women cutting their hair short took on new meanings, including entry into battle and (later) championing women's rights. During the 1850 Zanjan Babi rebellion, Zaynab, a woman from a peasant background, cut her hair and dressed as a man to join the men in battle. She took on the name Rustam ʿAlī as part of her male persona.Footnote 40 Read through Hallpike's insights, this episode suggests women's hair-cutting signified being subject to military discipline. It was also, ostensibly, a way of erasing gender boundaries or at least blurring them in much the same way that shaving a beard was for men, although to allow women to occupy male martial spaces in this case. In the early twentieth century, Ṭāyirah, a female Baha'i poet and champion of women's rights, had a portrait taken with short hair.Footnote 41 Her intention in cutting her hair short is unknown, but it was possibly an assertion of her role as a female intellectual whose worth was not tied to her hair.

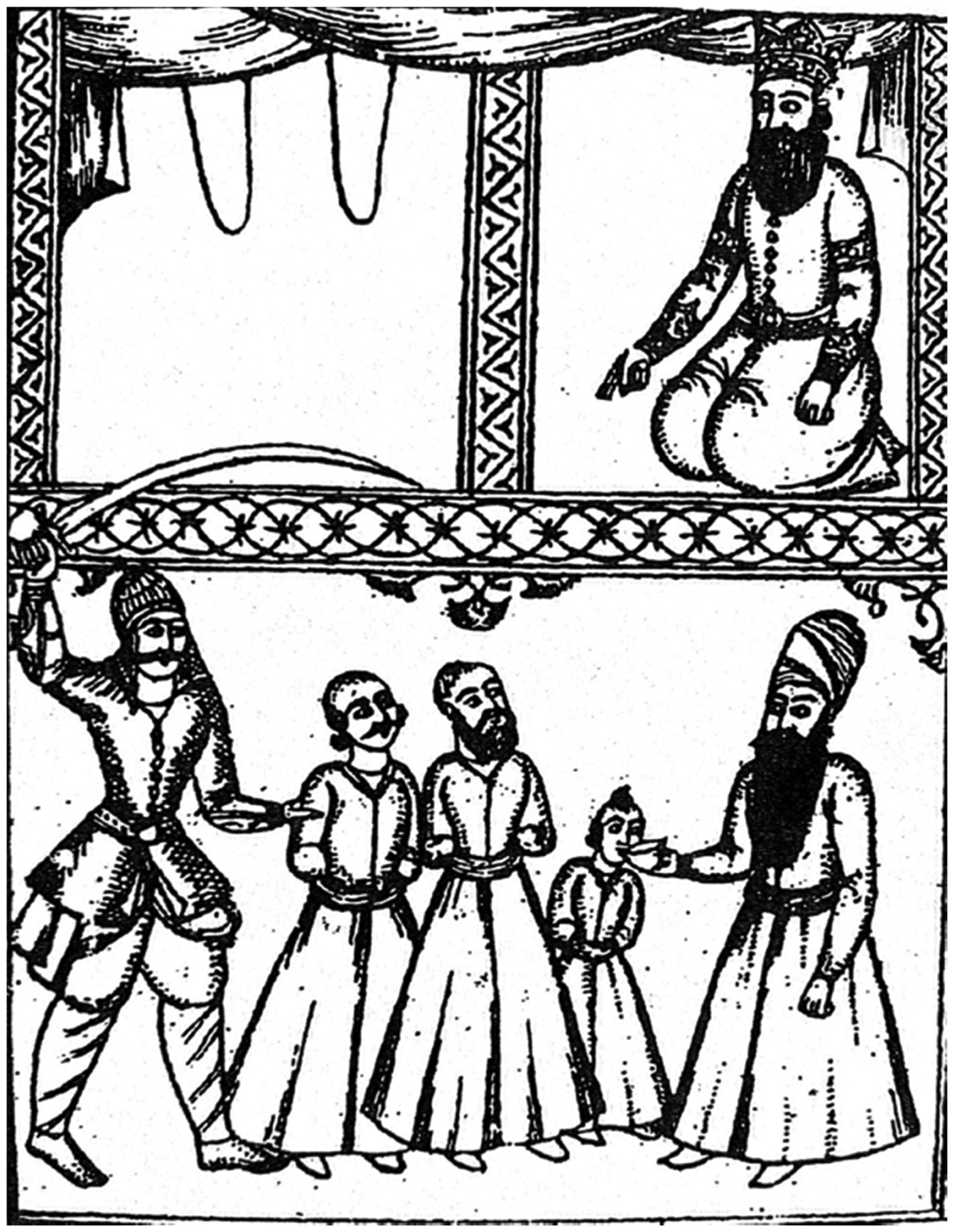

In contrast to voluntary acts, the forced cutting of hair was another matter altogether, as the emphasis was on humiliation and shame. According to the majority opinion in Islamic jurisprudence, a woman's hair was part of her nakedness (ʿawrah), with legal implications beyond mere veiling.Footnote 42 If an individual cut or shaved a woman's hair, it constituted an injury for which compensation equivalent to that of either a bride price or an intentional murder (diyah) was due: a full bride's price if the hair grew back and equivalent to an intentional murder if it did not, indicating that a woman's hair was a core component of her sanctity. Indeed, Shiʿi fiqh manuals explicitly forbid shaving an adulterous woman's hair while, at the same time, prescribing it for men.Footnote 43 The point of this punishment was exposure, and exposing a woman's bare head to the gaze of unrelated men undermined the potential intended goal of restoring community morality. Despite the lack of this punishment in Islamic jurisprudence for a female fornicator (and, by extension, a female prostitute or pimp), governments did use hair punishments for these crimes, primarily in cases of sexual deviance and immorality. Indeed, female prostitutes, pimps, and adulterers had their hair shaved, usually before being paraded on a pack animal backwards through the city or town. While there was clearly an element of publicness in the ritualistic exposure of shaved women's heads, there were rare instances of husbands carrying out such acts against their wives as a domestic disciplinary measure. A woman with cut locks (gīsū burīdah) was synonymous with shamelessness.Footnote 44 In “Sang-i Ṣabūr,” the folk story collected by Ṣādiq Hidāyat, a king punishes one of his faithless and treacherous wives by having her hair tied to the tail of a donkey who rides off into the desert.Footnote 45 A very similar scene was depicted in the nineteenth-century Persian lithograph Chihil Ṭūtī, where a king's two “lecherous” wives are executed in the same manner [see Image 1].Footnote 46 While these fictional narratives did not include shaving per se, they did associate the punishment for female illicit acts with hair. Within the domicile, husbands sometimes carried out retributive acts that mirrored the penal act of shaving a woman's hair. For instance, ʿAlī Akbar, the previous water carrier (ābdār) of ʿAlā al-Dawlah, became drunk, returned home, and fought with his wife in the ʿŪdlājān neighborhood of Tehran. During their altercation, he pulled out his knife, cut her tresses (gīsū-yi ū rā burīdah), and injured her hand.Footnote 47

Image 1. Women punished by having their hair tied to the tail of a donkey in a scene from Chihil Ṭūtī, dated 1851 (1268 H.).

Source: Ulrich Marzolph and Roxana Zenhari, Mirzā ʿAli-Qoli Khoʾi: The Master Illustrator of Persian Lithographed Books in the Qajar Period (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 2: 278.

Women's moral crimes, particularly prostitution and adultery, were occasionally punished by shaving their hair. This was in stark contrast to the early modern Ottoman context, where similar crimes were typically punished by fines, corporal punishment, or banishment.Footnote 48 In his 1861 German-language account, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh's Austrian physician, Jakob Eduard Polak, provided a broad picture of how prostitutes were punished for moral crimes. According to Polak, this punishment was usually “at the instigation of the ʿulamā” but carried out by government authorities. Prostitutes were rounded up, had their heads shaved, and were paraded around the city on donkeys before being banished.Footnote 49 Missing from this account, however, were the specificities of particular cases, as he claimed this punishment was used universally in Tabriz, Qazvin, Hamadan, and Qum. The account of Charles Wills, an English physician residing in Iran between 1866 and 1881, seems to corroborate Polak's general claims, although Wills addressed the case of an adulterous woman rather than a prostitute. Relaying the account of a Shirazi informant, Wills reported a woman being paraded bareheaded throughout town, her hair shaved off, sitting backwards on a donkey and accompanied by buffoons singing and dancing, with Jewish musicians forced to play the accompanying tunes. Unlike the prostitutes in Polak's case, she was not banished; instead, she was executed by being thrown down a well.Footnote 50

Persian sources often provide more concrete details than the schematic picture drawn by European observers. A summary report from early 1860s Shiraz described an instance in which a female pimp (jākish) hindered (zajr) a female guest from leaving her house where ten to fifteen people were present, presumably including unrelated men. This seems to have been a case of entrapment and procurement of the female guest. The city's chief attendant (Farrāshbāshī) caught the madam in question, had her tresses (gīs) shaved off, put her in a bridle, placed her on a pack animal, and paraded her around the bazaar so that others “would hold themselves accountable” (hisāb-i khūd rā bidānand). The spectacle had elements of bestialization (the bridle, the pack animal) and shaming (shaving hair and the parade) central to Qajar-era publicizing punishments.Footnote 51

Soldiers were often among those caught frequenting prostitutes or women deemed sexually immoral in nineteenth-century Iran. Women caught with soldiers in morally compromised positions seem to have been particularly singled out for punishment, possibly due to their threat to army discipline. In one instance in Shiraz, cavalrymen had a party at night in their barracks (sarbāzkhānah), brought “several immoral women” (chand zan-i kharāb), and drank and partied through the night. The governor ordered his attendants (farrāshān) to detain and imprison the women while keeping the cavalry in their barracks until morning. Instead, however, the cavalrymen beat up the attendants. When the governor learned of this, he sent attendants backed by soldiers to punish and beat the guilty cavalrymen as well as detain and imprison the women. In the morning, the governor ruled that the women's hair would be shaved and they would be released.Footnote 52 In another instance, an official of Fars Governor Farhād Mīrzā Muʿtamid al-Dawlah observed two women speaking with a soldier in the street and chastised and admonished (naṣīḥat) them. Instead of listening, however, the soldier injured the official, who then reported the case to the governor. The governor ruled that the two women be detained, have their hair shaved, and be paraded around in the streets.Footnote 53 On another occasion, several gunners hosted a woman at their house. The governor, Qavām al-Mulk, in addition to punishing the gunners, summoned the woman, had her hair shaved off, and paraded her around the streets and bazaar.Footnote 54

Despite this, not all shaving sentences seem to have been carried out, due to either popular objection to shaving and publicly parading women or because a fine was paid instead. In the summer of 1877, Muʿtamid al-Dawlah attended a case in which three women were proven to be prostitutes. In the government garden (bāgh-i ḥukūmatī) before a “public crowd” (dar malāʾ-i ʿāmm), he ruled that the chief executioner, Mīr Ghażab, shave the three women's heads and parade them around the bazaar without hijab. But public reaction to this ruling was unfavorable; people in the bazaar were upset and intended to “cause a disturbance” (khiyāl-i ghawghāʾī dāshtand). They asked, “What kind of action is this that is occurring in a Muslim land in punishing (tanbīh) women.” Before the punishment could be carried out, Qavam al-Mulk, the Kalāntar (police magistrate), stopped it.Footnote 55 This remarkable account suggests that people objected to the shaving punishment for women because it contravened shari‘ah, an objection consistent with the rules laid out in Islamic jurisprudence.

Finally, in a petition and report from the town of Khāf in Khurasan province dated December 23, 1886 (27 Rabīʿ al-Avval 1304 H.), the daughter of Mīr Ḥusayn was caught by her husband in the middle of “vile sex acts” (mubāshirat-i shanaʿātī) with a man named Aḥmad. The husband made the matter public (mas̱alah rā ʿumūmī kard) by petitioning (taẓallum) the local government. While the adulterous man was put in a bridle, had his ear cut off, and was paraded through the side streets and bazaars, the daughter was kept in the house of the local headman (kadkhudā) waiting for her hair to be shaved before her punitive parade. Before her punishment was implemented, however, her father interceded, arranged for a forty tumān fine (taʿāruf), and pleaded for her to be forgiven. According to the note on the ensuing investigation in the presence of the judge and deputy (khalīfah), Mīr Darvīsh Khān––a local official––accepted the forty tumāns in the presence of a council.Footnote 56

Women's hair punishments were distinctly sexual in nature; government officials not only punished women for their crimes, but also exposed and humiliated them by removing markers of their beauty and sexuality. Despite the gender difference, this paralleled the shaving of the lock punishment inflicted on amrads. Women's exposure for violating sexual norms flew in the face of Islamic jurisprudence, sometimes leading to popular objections to its violation of the shariʿah.

Removing Men's Facial Hair

The removal of a man's facial hair, including a beard or mustache, was a form of emasculation: a mature beardless man was, in a sense, naked and exposed.Footnote 57 Facial hair was one of the visible markers of manhood; its voluntary removal was, therefore, socially stigmatized.Footnote 58 Those who purposely shaved their own facial hair were known as amradnumā, or those who made themselves appear as beardless youth.Footnote 59 According to Ahmad Karamustafa, within the spiritual coordinates or certain forms of mysticism, such as the qalandariyah, the intentional removal of facial hair was meant to court social disapproval and blame, as “loss of hair symbolized loss of honor and social status.”Footnote 60 The Qalandar shaving of the hair, beard, mustache, and eyebrows was known as the “four blows” (chāhār żarb), which contravened the Prophetic tradition of long mustaches and beards.Footnote 61 Qalandars also viewed gazing upon the face of a beardless youth as a reminder of God's beauty, as the face was unobstructed by hair.Footnote 62 As a forcible act, the removal of facial hair could also be an extralegal form of retribution. In the romance narrative of Ḥusayn Kurd Shabistarī popular during the Qajar era, the protagonist rips the mustaches off the faces of his foes as an individual act of retribution expressed through dishonoring and emasculating the enemy.Footnote 63

Men voluntarily shaving their beards, intending to look like beardless youth, was itself a crime in many Muslim societies. In eighteenth-century Ottoman Damascus, for example, a governor forbade Muslims from shaving their beards and threatened to cut off the hands of any barber who aided them.Footnote 64 Safavid-era (1501–1722) farmāns also banned shaving beards. Shāh Ṭahmāsb prohibited beard shaving in a pietistic farmān dated September 16, 1534.Footnote 65 Later, Shāh Ṣafī banned the shaving of the beard in a farmān also regulating other illicit activities.Footnote 66 Safavid-era ʿulamā supported such measures in their own legal responsa (fatvās). For instance, the jurist Āqā Khānsārī issued fatvās prohibiting voluntary beard shaving despite his own private proclivity for beardless youth.Footnote 67

These formal prohibitions and rationales continued to be relevant well into the Qajar period. Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn Khān Kirmānī, for instance, argued that shaving the beard was an act committed by the people of Lot.Footnote 68 Muḥammad Shafīʿ Qazvīnī believed that had there been such beautiful amrads at the time of the Prophet Muhammad, there would be a Quranic verse requiring them to veil. He proposed that Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh issue a regulation (qarārdād) banning any man from shaving his beard. If the authorities caught a man doing so, they should be imprisoned for a few days, until the facial hair grew back. The purpose of this was to avoid them appearing barefaced (sādah) in public, as Qazvīnī believed that male beardlessness was akin to nudity.Footnote 69 The ʿulamā of the Qajar period continued to issue bans similar to their Safavid predecessors: Iʿtimād al-Salṭanah noted that the ʿulamā of Tehran prohibited men from shaving their beards and women from wearing a particular type of footwear, possibly a form of high heels, known as pāshnah nakhāb.Footnote 70

In the late Qajar period, the shaving of beards was often closely associated with the culture of the bathhouse (ḥammām). Indeed, the Shaykhī jurist Muḥammad Karīm Khān Kirmānī placed the sin both on the person who wanted their beard shaved and the bath attendant who did the shaving.Footnote 71 On April 22, 1841, in Isfahan, a certain Muḥammad Raḥīm Khān went to the door of a public bath in the Mīrābād neighborhood and asked the bath attendant (dallāk) to “shave [his] face” (ṣurat-i marā bitarāsh). The attendant refused, most likely because doing so was tantamount to being complicit in making the man look like an amrad. As a result, the two men exchanged words and came to blows. The police prefect (dārūghah) was informed of the situation, but by the time one of his men arrived, several people had already brought about a reconciliation.Footnote 72 Close to half a century later, several mullahs in Isfahan banned the city's bath attendants from shaving men's beards. When one dallāk broke this rule, a prominent ʿālim, Hājjī Sayyid Jaʿfar Bīdābādī, captured him and beat him thoroughly.Footnote 73

The lines between retribution and government-sanctioned punishment were blurred, however, especially in murder cases. In the medieval Mamluk Empire, a sultan's governor (walī) in Damietta was known for seizing assets, women, and youth. The locals rose up, raided his house, shaved off half his beard and mustache, put him on a camel, paraded him through town, and executed him.Footnote 74 In mid-nineteenth-century Isfahan, when the wife of a murdered man saw her husband's murderer, she ripped off his mustache with her bare hands and burned the remaining hairs with the flame of her lamp. He was then detained by city authorities.Footnote 75 After assassinating Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh in 1896, Mīrza Riżā Kirmānī was attacked by the crowd who witnessed the murder: one person ripped off his mustache, another tore off his beard, and another bit off his ear while others punched and wailed on him. The prime minister intervened and had him detained.Footnote 76

Within the penal context, medieval Muslim jurists viewed beard shaving as prohibited because it constituted a form of mutilation (muthlah).Footnote 77 Despite this, a number of government authorities still employed this specific form of punishment in Muslim societies. In 1696, a court witness who produced “fraudulent documents, had his beard shaved before being paraded through Cairo's markets on a camel, accompanied by a crier announcing his offenses to the crowds.”Footnote 78 This use of the beard shaving punishment was consistent in spirit, if not in letter, with the aforementioned shaving of head hair punishment for false accusations of zinā in Islamic jurisprudence. In early fourteenth-century Delhi, Sultan Muḥammad bin Tughlugh wanted to appoint a renown Sufi shaykh to an official post; when the latter refused, the sultan had his beard hairs plucked out before banishing him from the city.Footnote 79 The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babur, threatened those within his troops who stood by while other warriors fought opposing Afghans with being “paraded around town with your beards cut so that anyone who lets such an enemy defeat such a warrior and stands by watching on such flat ground without lifting a finger may get his just deserts.”Footnote 80 In early modern Iran, the clipping of the mustache functioned as a way of erasing differences among Muslims. The father of Muṣliḥ al-Dīn Lāri was known for patrolling the streets of Lār and clipping the “luxuriant mustaches” that Shiʿis were known to sport prior to the ascendance of the Safavids.Footnote 81 Shāh Ṭahmāsb had Amīr Qavām al-Dīn, the leader of the Nūrbakhshiyyah Order, interrogated in his presence by a judge (qāżī) before deciding that Qavām al-Dīn had acted more like a king than a dervish, especially as he had been amassing arms. After his interrogation, Qavām al-Dīn was imprisoned, had his beard set on fire, and was finally executed.Footnote 82

Drawing perhaps on this same repertoire, similar punishments were meted out during the Qajar period. Fatḥ ʿAlī Shāh had the beard of Ḥājjī Hāshim Khān, an upstart rebel in Isfahan, shaved with a dull razor as part of his slow ritualistic execution.Footnote 83 Based on an ʿulamā complaint to Governor Ḥusayn Khān Ajūdānbāshī in Shiraz, the early Babi Mullā Ṣādiq and his companions were arrested for preaching the new message in the Bāqirābād Mosque. The governor had them beaten with sticks, their beards burnt, and bridled and paraded them through the city.Footnote 84 Early in his reign in 1861, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh punished the police magistrate of Tehran, Maḥmūd Khān Kalāntar, for failing to keep order amidst serious, famine-related bread riots by having his beard shaved off, beaten with sticks, and then strangled to death.Footnote 85 Around the same time, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh ordered that Qajar princes who recited offensive satirical poetry (hajviyah) have their beards shaved.Footnote 86 Later in his reign, however, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh appears to have accepted such punishments as excessive and unnecessary cruelty; at the very least, he no longer wanted his governors to implement them. Having recently banned torture and excessive punishment, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh considered beard shaving to be an extralegal example of the same. In Bujnūrd, Governor Sahām al-Dawlah shaved the beards of criminals and threw them off roofs. The shāh considered these to be illegal actions (ḥarakāt-i khalāf-i qāʾidah) and asked the official Āṣif al-Dawlah to chastise the wayward governor.Footnote 87

Paradoxically, the cutting of facial hair was deemed a crime when done voluntarily but a punishment when done forcibly. Those who challenged government authority or violated prevailing orthodox religious norms were especially singled out for facial hair punishments, as such signified a loss of status, emasculation, or an act of retribution.

Bareheaded and Hat Punishments

In many Muslim societies, social attitudes dictated that men and women both cover their heads. As James Grehan notes, only a Sufi considered extraordinarily pious could appear bareheaded, which was also sometimes understood as a divine form of madness.Footnote 88 Being bareheaded (sar barahnah) was a form of exposure for both men and women, although much more consequential for women. Since headgear was one of the most prominent markers of status, its removal constituted a stripping of belonging to a legible status group, whether a tribe, profession, or religious group. In a sense, being bareheaded signified bare life; ejection from a social group meant entering the realm of the bestial. According to Esther Cohen, nudity and the divestiture of clothing were the most common mechanisms of status deprivation in medieval France.Footnote 89 Divestiture and nudity were preparatory stages for capital punishment. She argues convincingly that “nudity was thus a symbolic social death.”Footnote 90 The public removal of a man's headgear by an authority, especially during a ritual penal parade, signified humiliation and punishment during the Qajar era.Footnote 91 In Persian, there is a strong association between having one's hat removed and being made a fool, as illustrated by the expression “having [one's] hat removed” (kulāh bardāshtan). In fact, the person who removes the hat (kulāhbardār) is a trickster or thief.Footnote 92

In nineteenth-century Iran, explicit references were made to people being paraded around bareheaded, including prominent religious figures and dissidents considered a threat to the ʿulamā and/or government authorities. Three striking instances included Babi movement founder Sayyid ʿAlī Muḥammad (the Bāb), the founder of the Baha'i religion, Baha'u’llah, and the Pan-Islamist Jamāl al-Dīn Asadābādī, popularly known as al-Afghānī. In the lead-up to his execution in Tabriz's Sabzahkhānah Kūchak Maydān, the Bāb was paraded around the city with a bare head and bare feet. His turban and sash––markers of his status as a sayyid––had been removed. Not only was this intended to shame and expose the Bāb, but also reduce him to bare life before his execution in 1850. As it was generally taboo to shed the blood of a descendant of the Prophet Muḥammad (sayyid), removing visible markers of such descent was likely symbolically necessary to making such an extraordinary act possible.Footnote 93 The Bāb and Baha'u’llah, the later founder of the Baha'i Faith, had similar experiences of being paraded without headgear, but to prison rather than an execution site. Baha'u’llah recounted having his feet chained and a man, possibly an attendant or executioner, snatching the hat off his head while parading him bareheaded and barefooted to Siyāh Chāl Prison in Tehran in 1852.Footnote 94 Finally, Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, who resided in Tehran for some time and whom the authorities suspected of seditious activities, was forcibly dragged out of the sanctuary of Shāh ʿAbd al-ʿAẓīm by government attendants in 1891. After the attendants kicked and beat him, al-Afghānī was taken out in the snow bareheaded and barefoot. At one point, even his drawstrings loosened, and his genitals were exposed. Later, when he was about to be exiled from the city and country, he was forced to remove his turban once more, put on a pack horse (asb-i pālānī), and had his feet bound by chains from under the animal.Footnote 95

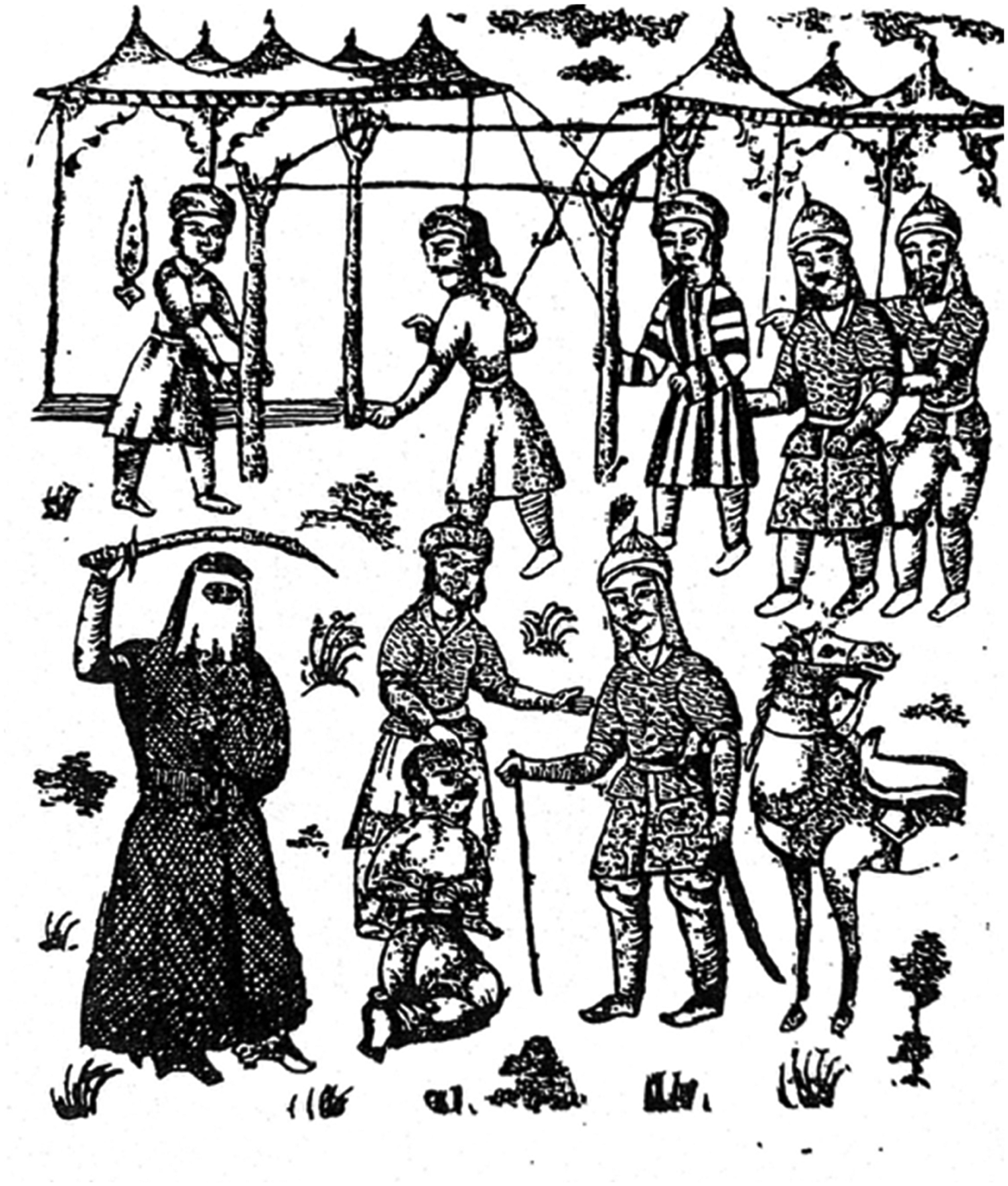

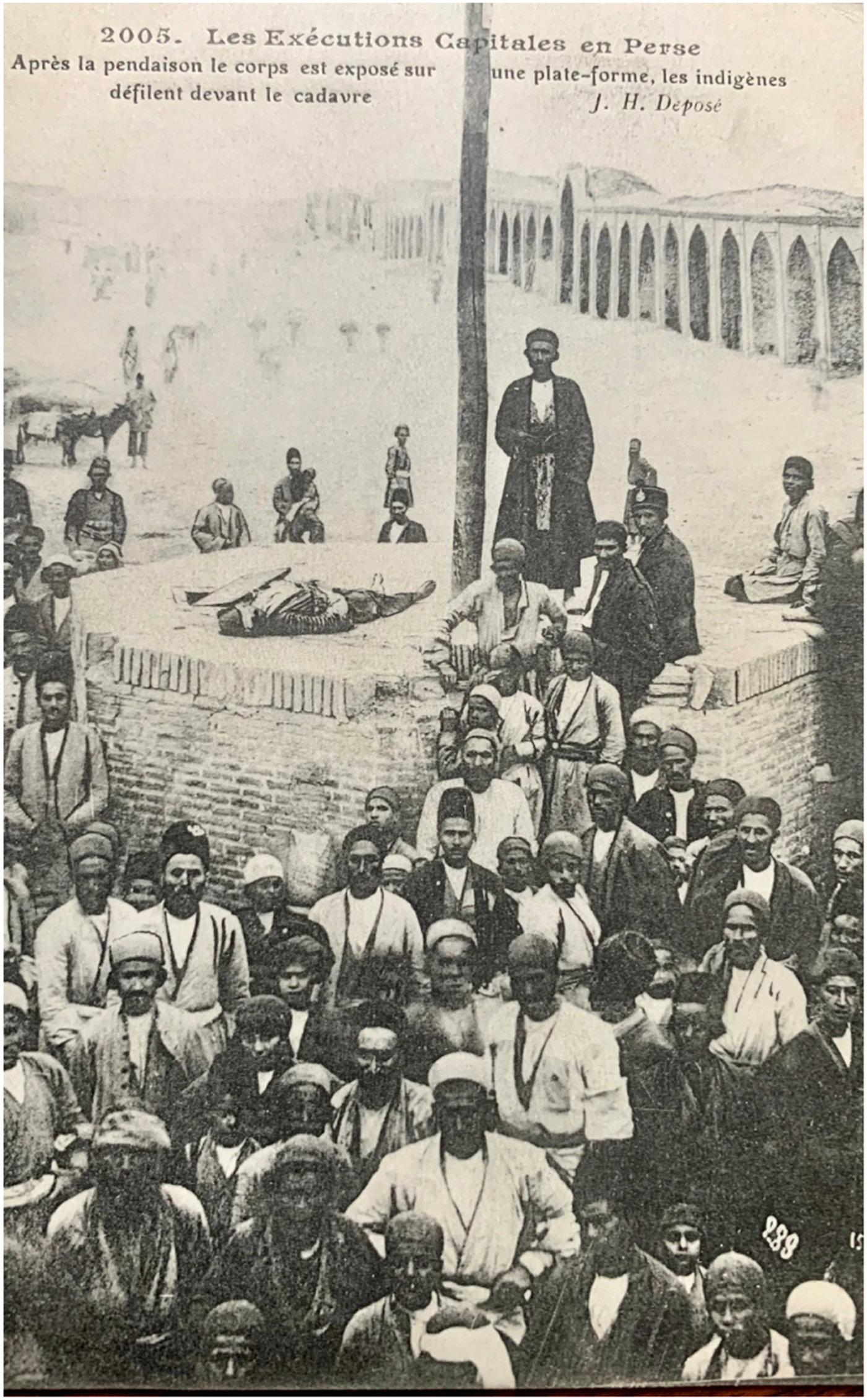

Visual evidence from nineteenth-century Iran, whether photographs or lithographic images, rarely presents a criminal with any sort of headgear on, especially those being taken to the gallows.Footnote 96 In the early 1860s, the official state newspaper included the execution scene of a religious teacher who had raped and later killed his young male student. The lithograph sketch depicts the boy's uncle as he is about to behead the murderer. Strikingly, the condemned man is bareheaded while all other males in the scene are wearing headgear [See Image 2].Footnote 97 This lends credence to the notion that the removal of social status markers and reduction to bare life were necessary preludes to legal executions. While this example was based on a historical incident, lithographic scenes of captured criminals from fictional works also depict the men as bareheaded. In one scene, for instance, three criminals about to be beheaded are shown bareheaded [See Image 3].Footnote 98 In another execution scene, a veiled woman prepares to execute a bound, bareheaded man [See Image 4].Footnote 99 Photographic evidence of corporal and capital punishment further substantiates that criminals were almost always bareheaded during their punishment. A photo of a man after his beheading at the gallows in Tehran shows no hat or headgear near him [See Image 5].Footnote 100 Shaykh Maẕkūr Khān ʿArab, who rebelled against the Qajars and minted coins, was publicly hanged bareheaded in Shiraz for his seditious activities [See Image 6].Footnote 101 Again in Shiraz, a man about to be blown out of a cannon had his disheveled hair on full display for the camera before his eventual death [See Image 7].Footnote 102

Image 2. A murderer-rapist about to be beheaded in Shiraz.

Source: Rūznāmah-i Dawlat-i ʿIlliyah-i Īran, n.504 (10 Jumādī al-Avval 1278 H./13 November 1861).

Image 3. Three criminals about to be beheaded in a scene from the Persian lithograph Akhlāq-i Muḥsinī, dated 1851 (1268 H.).

Source: Ulrich Marzolph, Narrative Illustration in Persian Lithographed Books (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 99.

Image 4. A veiled woman about to execute a bareheaded man in a scene from the Persian lithograph Mukhtārnāmah, dated 1845 (1261 H.).

Source: Ulrich Marzolph, Narrative Illustration, 72.

Image 5. Photo of a beheaded man in late nineteenth-century Tehran.

Source: Antoin Sevruguin, “Criminal Execution Persia, Late 19th Century,” The Nelson Collection of Qajar Photography, https://www.thenelsoncollection.co.uk/artists/26-antoin-sevruguin/works/9762/

Image 6. The hanging of Shaykh Maẕkūr Khān ʿArab in nineteenth-century Shiraz.

Source: ʿAlī Akbar Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, ed., Vaqāyiʿ-i Ittifāqīyah: Majmūʿah-i guzārishhā-yi khufiyah nivisān-i Inglīs dar Vilāyāt-i Junūbī-i Īran az sāl-i 1291 tā 1322 h.q. (Tihrān: Nashr-i Naw, 1982), recto 201.

Image 7. A man about to be blown out of a cannon in late nineteenth-century Shiraz.

Source: Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, Vaqāyiʿ-i Ittifāqīyah, recto 431.

If being bareheaded constituted one form of shaming, being forced to wear a hat not suited to one's social status was another. For men in the Ottoman Empire, and arguably throughout many Muslim societies, turbans were a marker of social rank.Footnote 103 Islamic primary school (maktab) teachers in Iran disciplined lazy children by making them stand in front of the class wearing a paper hat and their clothes on backwards, in a manner reminiscent of the dunce cap in England.Footnote 104 In an educational setting, this disciplinary action directly mirrored the shaming function of ritualistic hat punishments. Similar to removing a hat, placing a hat on someone's head (kulāh bar sar-i kasī guẕāshtan) connoted tricking or making a fool of them in the Persian language.Footnote 105

The elements that made a hat so ridiculous and shameful included the material from which it was made, such as felt or paper, or its fit, which was usually too wide for the person's head and slid down their face. In medieval Islamic ḥisbah manuals, those punished in this manner had to wear hats with special bells on them, bringing to the fore an auditory dimension and perhaps equating the person with a pack animal wearing a bell. Such punishments were also gendered: sources only speak of men being punished in this manner. The Persian term takhtah kulāh refers to a wooden hat with bells that is placed on the heads of criminals.Footnote 106 In the Safavid era, Jean Chardin noted the use of this punishment on those who used false measures in the bazaar. The criminal was made to wear a wooden board with a bell in front and a long straw cap (un haut bonnet de paille) before being paraded around the neighborhood to the jeers of the local rabble.Footnote 107 On the other hand, Engelbert Kaempfer described the hat as very wide, covering the head and shoulders, and adorned with bells and a single fox tail.Footnote 108 The Persian eighteenth-century administrative manual Taẕkirat al-Mulūk made it the muḥtasib's responsibility to use the takhtah kulāh to punish those violating bazaar regulations: “As regards the prices (tasīʿrāt) of the goods sold by the traders (asnāf) to the inhabitants of the town, if any of the professional merchants (ahl-i hirfa) eludes the Muḥtasib's regulations (qarār-dād), the latter makes him takhta-kulāh, that he may serve as an example to others.”Footnote 109

Hat punishments connoted shame and compromised status. In early modern France, the condemned were sometimes made to wear a paper bonnet––the equivalent of the paper hat (kulāh kāghazī) punishment in Iran––as part of their humiliation ritual.Footnote 110 Those whose hat was replaced with a silly one were almost always from a recognized or honored status group, thus making their shame all the more pronounced. A prominent governor of Khurasan, Mīrzā Muḥammad Qavām al-Dawlah, who was partly responsible for the loss of the Marv to the Turcomans in the 1850s, was among the most well-documented nineteenth-century examples of hat punishment. Upon his shameful return to Tehran, Nāṣir al-Dīn Shāh ordered that Qavām al-Dawlah be put on an old, decrepit horse (yābu), made to wear a silly hat, and paraded around the city by the chief executioners. Sources disagree on whether this was a felt hat (kulāh namadī), a wide hat “pulled down close to his nose,” or a paper hat (kulāh kāghazī).Footnote 111 ʿAbdullāh Mustawfī claims that, in addition to wearing a felt hat, Qavām al-Dawlah was also made to wear a faded, rough cotton (karbāsī) cloak, worn-out underwear, and thick wooden shoes.Footnote 112 ʿAyn al-Salṭanah, who appears as an eyewitness to the episode, narrated that Qavām al-Dawlah paid the executioners to take him on side streets to lessen his public humiliation.Footnote 113

In a case from roughly the same time, a mullah in Isfahan was exposed in this way for providing false testimony (shahādat-i nā ḥaqq) in exchange for a bribe (rishvat). When the central government's Court of Justice (Dīvānkhānah-i Mubārakah) received news of this, it ruled he be punished in the following manner: his turban was removed and a hat put on his head (kulāh bar sarash guẕāshtand), signifying “he was an untrustworthy person and not in the path of the ʿulamā of religion.”Footnote 114 In this instance, the removal of the turban signaled exclusion from his religious status group: the loss of the turban for a mullah and the wearing of a regular hat was a symbolic expulsion from the ranks of the ʿulamā. That this was done in a case of false testimony is also significant insofar as, in Islamic history, there were precedents for hair shaving functioning in the same way for such legal violations. Thus, it could be said that the hat punishment was functionally equivalent to the hair-shaving punishment.

Conclusion

On September 16, 2022, Mahsā (Zhīnā) Amīnī was brutally murdered by the Iranian morality police after being arrested for improperly wearing her hijab. In the ensuing protests that erupted across Iran and the world, women and sometimes men cut or shaved their hair in solidarity. Turning to history, many commentators sought precedents for this act, particularly in Persian literature, understanding it as signifying intense mourning and/or protest against injustice.Footnote 115 Notably absent from such commentaries, however, was the historical penal meaning of shaving women's hair; one meant to inflict shame for her supposed sexual immorality. In light of the arguments made here, women shaving their hair can perhaps be read as a defiant act of inversion, turning cultural logic on its head by making women's shaved hair a marker of honor rather than disgrace.Footnote 116

In nineteenth-century Iran, both a person's hair and headgear were core components of their public persona. There were cultural expectations that one's hair and head be presented appropriately, the violation of which constituted a form of deviance. Hair, especially, had sacred dimensions governed by prohibitions and regulations regarding its length, shaving in ritual settings, and presentation in public settings. Hair was also tied to one's sexuality and even beauty. Forced hair cutting, the removal of headgear, or the placement of silly headgear were all effective methods of shaming. These punishments brought together elements of control and subordination with ritualistic punishment.

The shaving of head and facial hair, the removal of the hat, and the forced wearing of a silly hat were all punishments symbolically associated with shaming. Furthermore, such punishments were almost always public in two ways: first, the condemned were usually paraded around the city or town in such a way that others would see them in their humiliated state; and second, the punishment itself was a bodily or sartorial alteration communicating that the condemned had committed a crime. The types of crimes associated with this punishment usually fell into three broad categories. The first and most common had to do with sexual crimes such as fornication, adultery, homosexuality, prostitution, and pimping. The strong connection between hair and nakedness in the case of women, and between hair and manhood in the case of men, seems to have amplified this meaning. Second, those considered to have rebelled against or failed in their duties to the government or religious orthodoxy were also singled out for these punishments. Thus, we see prominent figures deemed to be heretics, leaders of protest movements, and a governor losing territory punished by either appearing bareheaded or forced to wear a silly hat. Finally, Jews––Jewish musicians and sometimes alcohol distributors more specifically––had their locks shaved for supposed moral crimes. In cases involving Jews, a Shiʿi jurist stressed their differentiation from and subordination to Muslims. Conceptually, we can consider how these punishments were carried out by different actors, in ways that were sometimes legal and other times informal. The government or ʿulamā were usually the agents issuing rulings for such punishments. At the informal level, individuals or collectives used such punishments as forms of retaliation against enemies or those who had somehow wronged them. Within the domicile, husbands forcibly cut their spouses’ hair in domestic disputes. Hair shortening or shaving punishments constituted being subject to a disciplinary regime, one that highlighted subordination. The ritualistic dimension of these punishments was often central to hair and hat punishments, which almost always involved a parade on a pack animal and exposure to jeering crowds.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Serpil Atamaz, Houchang Chehabi, Farshid Kazemi, and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and critiques. I am also grateful to Sholeh Quinn and Dominic Brookshaw for providing me with useful scholarly references, Farhad Dokhani for tracking down a rare source that was otherwise inaccessible, and my research assistant, Sayeh Khajeheiyan, for diligently transcribing Persian archival materials. This article is dedicated to the brave women and men of the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement in Iran.