Racial and ethnic health disparities are persistent and costly, carrying massive negative social, health, and fiscal consequences (Ayanian, Reference Ayanian2015; National Center for Health Statistics, 2021; Weinstein et al., Reference Weinstein, Geller, Negussie and Baciu2017). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ ambitious Healthy People 2020 initiative aimed to eliminate health disparities by 2020, but this goal was far from achieved in many areas. In fact, some racial/ethnic disparities even worsened over time, including rates of adolescent depression and suicide (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a, 2016b). Further, higher rates of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms are found among children and adolescents of color compared to White populations (Alegria et al., Reference Alegria, Vallas and Pumariega2010, Reference Alegria, Greif Green, McLaughlin and Loder2015; Bogart et al., Reference Bogart, Elliott, Kanouse, Klein, Davies, Cuccaro, Banspach, Peskin and Schuster2013; Price et al., Reference Price, Khubchandani, McKinney and Braun2013). These inequities warrant widespread concern and attention and become ever more pressing as children of color move into the “diverse majority,” rather than the minority, of the U.S. youth population (as of 2020; Society for Research in Child Development, 2021).

The seminal Integrative Model for the Study of Developmental Competencies in Minority Children (hereafter referred to as the Integrative Model) introduced a new framework for studying development among youth of color (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, Pipes McAdoo, Crnic, Hanna Wasik and Vázquez García1996; Perez-Brena et al., Reference Perez-Brena, Rivas-Drake, Toomey and Umaña-Taylor2018). A central tenet of this model is the need to recognize and study unique forms of oppression as important contributors to developmental outcomes for racially/ethnically diverse youth (Causadias & Umaña-Taylor, Reference Causadias and Umaña-taylor2018; García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, Pipes McAdoo, Crnic, Hanna Wasik and Vázquez García1996). Similarly, there are growing calls from health disparities researchers to situate all discussion of racial/ethnic disparity within the context of structural racism (Boyd, Lindo, et al., Reference Boyd, Lindo, Weeks and McLemore2020; García & Sharif, Reference García and Sharif2015; Marks et al., Reference Marks, Woolverton and García Coll2020). In other words, it cannot be overstressed that race in and of itself is not a risk factor for persisting racial/ethnic health disparities; rather it is the cumulative impact of multiple forms of racial oppression, including inequitable access and treatment across economic opportunity, intergenerational wealth, and virtually all public systems (including child welfare, criminal justice, health, and education), all of which work together synergistically to persistently undermine the health of people of color (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Krieger, Agénor, Graves, Linos and Bassett2017, Reference Bailey, Feldman and Bassett2021; Boyd, Lindo, et al., Reference Boyd, Lindo, Weeks and McLemore2020; García & Sharif, Reference García and Sharif2015; Gee & Ford, Reference Gee and Ford2011; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020). This understanding is supported by a large body of research (Alegria et al., Reference Alegria, Greif Green, McLaughlin and Loder2015; Koh et al., Reference Koh, Graham and Glied2011; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Priest and Anderson2016). However, less explicitly studied and discussed are the ways in which these challenges likely transmit health risk biologically across generations through mechanisms related to the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD; Conradt et al., Reference Conradt, Carter and Crowell2020).

Developmental origins of health and disease and child mental health

The DOHaD model suggests that adversity in prenatal and early life influences biological systems and impacts physical and mental health across the lifespan (Barker, Reference Barker2007; Gluckman et al., Reference Gluckman, Buklijas and Hanson2016; Hentges et al., Reference Hentges, Graham, Plamondon, Tough and Madigan2019). This model includes the idea of fetal programing, wherein fetal development is impacted by changes to the intrauterine environment as a result of maternal context, including biological and psychological adversity. DOHaD and fetal programing hypotheses are supported by research linking prenatal maternal stress, mood, and adversity to the fetal environment and to adverse birth outcomes, disrupted motor and cognitive development, long-term health risks such as obesity and cardiometabolic disorders, and mental health challenges including depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and more general internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Davis & Sandman, Reference Davis and Sandman2010, Reference Davis and Sandman2012; Essau et al., Reference Essau, Sasagawa, Lewinsohn and Rohde2018; Glynn et al., Reference Glynn, Howland, Sandman, Davis, Phelan, Baram and Stern2018; Graignic-Philippe et al., Reference Graignic-Philippe, Dayan, Chokron, Jacquet and Tordjman2014; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Swales, Garcia, Driver and Davis2019; Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Davis, Hobel, Coussons-Read and Dunkel Schetter2020; Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Kim, Shin, Yoo, Lee and Cho2014; Racine, Plamondon, et al., Reference Racine, Plamondon, Madigan, McDonald and Tough2018; Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Buss, Head and Davis2015; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer, Hoyer, Roseboom, Räikkönen, King and Schwab2017). Importantly, studies attempting to understand psychiatric risk earlier in life have identified negative emotionality in infants, which includes frustration, fear, discomfort, sadness, and low soothability (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart2007), as an indicator of future mental health challenges (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Jones-Mason, Coccia, Caron, Alkon, Thomas, Coleman-Phox, Wadhwa, Laraia, Adler and Epel2017; Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Schrock and Woodruff-Borden2011; Luecken et al., Reference Luecken, MacKinnon, Jewell, Crnic and Gonzales2015).

Sociocultural stressors

Although there has been substantial growth in evidence supporting DOHaD and links between maternal stress and child development, there has been relatively little focus in this area on sociocultural stressors that disproportionately impact communities of color (Conradt et al., Reference Conradt, Carter and Crowell2020; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015; Liu & Glynn, Reference Liu and Glynn2021). In fact, there is a dearth of research that examines preconception or prenatal influences of offspring behavioral development among diverse and/or low-income populations, despite the greater risk of exposure to stress within these communities (Bush et al., Reference Bush, Jones-Mason, Coccia, Caron, Alkon, Thomas, Coleman-Phox, Wadhwa, Laraia, Adler and Epel2017; Conradt et al., Reference Conradt, Carter and Crowell2020; Demers et al., Reference Demers, Aran, Glynn and Davis2021). Therefore, guided by both DOHaD and the Integrative Model, we examine two prevalent stressors among populations of color in the current study – discrimination and acculturative stress – as potential prenatal stressors related to offspring mental health.

Discrimination refers to unjust, unequal, or biased attitudes or behavior towards an individual because of their race, sex, class, or other characteristics. Importantly, women of color often hold multiple marginalized and minoritized identities (including gender and race/ethnicity) and are therefore at higher risk of experiencing multiple forms of discrimination (Earnshaw et al., Reference Earnshaw, Rosenthal, Lewis, Stasko, Tobin, Lewis, Reid and Ickowvics2013; Watson et al., Reference Watson, DeBlaere, Langrehr, Zelaya and Flores2016). Acculturative stress describes the stress of adapting to new cultures, including new dominant behaviors, customs, schools of thought, and values (Berry, Reference Berry1997; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015; Sam & Berry, Reference Sam and Berry2010). Acculturative stress is often discussed in the context of immigrant populations, however, it has also been described as a phenomenon facing all members of historically nondominant cultural groups within the US (Walker, Reference Walker2007). Both discrimination and acculturative stress have been linked to maternal mental health (Canady et al., Reference Canady, Bullen, Holzman, Broman and Tian2008; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015; Ertel et al., Reference Ertel, James-Todd, Kleinman, Krieger, Gillman, Wright and Rich-Edwards2012). Discrimination has also been associated with physiological change during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes such as preterm birth and low birthweight (Alhusen et al., Reference Alhusen, Bower, Epstein and Sharps2016; Chaney et al., Reference Chaney, Lopez, Wiley, Meyer and Valeggia2019; Dominguez et al., Reference Dominguez, Dunkel-Schetter, Glynn, Hobel and Sandman2008; Giurgescu et al., Reference Giurgescu, McFarlin, Lomax, Craddock and Albrecht2011; Hilmert et al., Reference Hilmert, Dominguez, Schetter, Srinivas, Glynn, Hobel and Sandman2014). Although there is very little existing research examining the impact of preconception or prenatal maternal exposure to discrimination or acculturative stress on offspring health, one recent study did find an association between prenatal discrimination and negative emotionality and inhibition/separation problems among infant offspring (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Earnshaw, Moore, Ferguson, Lewis, Reid, Lewis, Stasko, Tobin and Ickovics2018). These findings support existing concerns regarding intergenerational impact of sociocultural stressors and highlight the urgent need for further study in this area.

Resilience-promoting factors

In addition to calling for recognition of unique cultural contexts and oppressive systems facing populations of color, García Coll’s Integrative Model emphasizes the importance of identifying factors that contribute to positive development (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, Pipes McAdoo, Crnic, Hanna Wasik and Vázquez García1996). In the current study, we are particularly interested in factors contributing to resilience, or adaptation and wellness in the presence of adversity and risk (Masten & Coatsworth, Reference Masten and Coatsworth1998; Rutter, Reference Rutter1987). Resilience processes can be (a) compensatory/promotive, when a resource exerts a main, positive effect on an adaptive outcome in the presence of a risk factor; or (b) protective, when a resource reduces the relation between a risk factor and maladaptive outcome, as reflected in an interaction effect of the risk factor and resource on outcome (Fergus & Zimmerman, Reference Fergus and Zimmerman2005; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Stoddard, Eisman, Caldwell, Aiyer and Miller2013; Zolkoski & Bullock, Reference Zolkoski and Bullock2012). Few studies have addressed specifically the pre- or postnatal resilience-promoting factors that contribute to infant mental health. Therefore, for this exploratory investigation, we informed our selection of resilience-promoting factors with both theory and evidence. Following the Integrative Model’s emphasis on different ecologies that surround a developing child (e.g., family and community), as well as culturally specific influences (i.e., communalism) (Cabrera, Reference Cabrera2013; García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Akerman and Cicchetti2000; Perez-Brena et al., Reference Perez-Brena, Rivas-Drake, Toomey and Umaña-Taylor2018; Umaña-Taylor et al., Reference Umaña-Taylor, Toomey, Williams and Mitchell2015), we chose to investigate three domains of resilience-promoting factors with existing empirical support outside of infant mental health – social capital, communalism and parenting self-efficacy.

Community cohesion and social support encompass two facets of social capital that have been linked to reduced levels of stress and other mental health problems (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Zhang and Walton2014; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019; Saleem et al., Reference Saleem, Busby and Lambert2018; Svensson & Elntib, Reference Svensson and Elntib2021; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Kimura, Cui, Kubota, Ikehara and Iso2021). Social support refers to one’s network of social connections that provide both emotional and tangible forms of support, while community cohesion is defined as the presence of mutual trust and solidarity within one’s local community (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). Although both community cohesion and social support have been related to better birth outcomes, albeit inconsistently (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Dunkel-Schetter, Sandman and Wadhwa2000; Hetherington et al., Reference Hetherington, Doktorchik, Premji, McDonald, Tough and Sauve2015; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, 2019; Schetter, Reference Schetter2011), less research has examined the relation between prenatal maternal social capital and child outcomes.

Communalism is a cultural orientation towards interdependence (and thought to stand in contrast to the Eurocentric value of independence) that emphasizes social bonds, social duties, and the importance of collective well-being, both outside and within one’s family (i.e., familism) (Abdou et al., Reference Abdou, Dunkel Schetter, Campos, Hilmert, Dominguez, Hobel, Glynn and Sandman2010; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Weisskirch, Hurley, Zamboanga, Park, Kim, Umaña-Taylor, Castillo, Brown and Greene2010). Communalism has been highlighted by researchers as a potential culturally specific resilience-promoting asset for racially/ethnically diverse populations, including Black, Latinx/Hispanic, and Asian American groups (Moemeka, Reference Moemeka1998; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Weisskirch, Hurley, Zamboanga, Park, Kim, Umaña-Taylor, Castillo, Brown and Greene2010; Woods-Jaeger et al., Reference Woods-Jaeger, Briggs, Gaylord-Harden, Cho, Lemon and Woods-2021). However, evidence has been mixed in its level of support for this hypothesis (Abdou et al., Reference Abdou, Dunkel Schetter, Campos, Hilmert, Dominguez, Hobel, Glynn and Sandman2010; Gaylord-Harden & Cunningham, Reference Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham2009; Harris & Molock, Reference Harris and Molock2000), and some scholars have suggested that higher levels of communalism may sensitize one to the presence of stressors such as discrimination (Goldston et al., Reference Goldston, Molock, Whitbeck, Murakami, Zayas and Hall2008; Perez-Brena et al., Reference Perez-Brena, Rivas-Drake, Toomey and Umaña-Taylor2018).

Finally, the concept of parenting self-efficacy is grounded in social cognitive theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura1997) and describes a caregiver’s confidence in their ability to parent successfully. Self-efficacy is informed both by one’s individual beliefs as well as their observations and experiences in their environment (Bloomfield & Kendall, Reference Bloomfield and Kendall2012; Raikes & Thompson, Reference Raikes and Thompson2005). Parenting self-efficacy has been linked to better psychological health and adjustment among both children and parents (Albanese et al., Reference Albanese, Russo and Geller2019; Wittkowski et al., Reference Wittkowski, Garrett, Calam and Weisberg2017), but there is a lack of research on parenting self-efficacy in the context of sociocultural stressors.

Current study

Drawing on the Integrative Model’s framework for studying unique determinants of risk, as well as resilience among youth of color (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, Pipes McAdoo, Crnic, Hanna Wasik and Vázquez García1996), and DoHAD’s emphases on early life antecedents of health and development (Barker, Reference Barker2007; Gluckman et al., Reference Gluckman, Buklijas and Hanson2016), the current study prospectively examines intergenerational risk and resilience pathways to infant mental health. Specifically, we examine risk pathways by testing relations between sociocultural stressors assessed prenatally (discrimination and acculturative stress) and infant offspring negative emotionality. We test for both compensatory/promotive and protective resilience pathways by assessing main and interactive associations (with sociocultural stressors) of community cohesion, social support, communalism, and parenting self-efficacy with negative emotionality. Given the dearth of existing research on maternal prenatal sociocultural stress, infant temperament, and resilience-promoting factors, this was largely an exploratory study. We did anticipate sociocultural stress to be associated with infant negative emotionality, and that resilience-promoting factors may buffer these relations.

Method

Participants

Study participants were a subsample of 113 mothers and their children (53% male) who identified as a race or ethnicity other than White, drawn from a larger longitudinal study beginning in pregnancy. Our sample consisted of 69% of mothers self-identifying as Latinx/Hispanic, 15% as Asian American, 11.5% as Multiethnic, and 4.4% as Black.Footnote 1

Participants were recruited from Southern California medical clinics during their first trimester of pregnancy. Inclusion criteria included singleton intrauterine pregnancy, being 18 years of age or older, English-speaking, absence of tobacco, alcohol, or drug use during pregnancy and medical conditions impacting endocrine, cardiovascular, hepatic, or renal functioning. Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. On average, mothers were 28 years old (SD = 5.65, range = 18.05–41.57) with a median household income of $52,158. Approximately a third of participants (31.9%) were born outside the U.S. Similarly, about a third of the sample spoke a language other than English in their household (35.4%). There was also a wide distribution of maternal education level, with 30.1% completing high school or less, 49.6% having some college, an associate degree, or a vocational or certificate program degree. Lastly, 20.3% of the sample had completed college or graduate school.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the responsible Human Subjects Review Board. Study subjects participated in a series of pre- and postnatal study visits that included questionnaires and structured interviews to collect information on maternal and infant demographics, mood, health, risk, resilience, and infant development. The current study sample includes all participants who completed the 12-month postpartum study visit. Supplementary Table 1 provides an overview of data collection.

Measures

Gestational age at birth (GAB) was determined using the last menstrual period and an ultrasound prior to 20 weeks gestational age, in line with guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstretic Practice, 2017).

Sociocultural stressors

Acculturative stress was measured at a 25-week prenatal visit with the Societal, Attitudinal, Environmental, and Familial Acculturative Stress Scale short version (SAFE; Mena et al., Reference Mena, Padilla and Maldonado1987). Subjects were asked to rate the stressfulness of 24 items on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., “It bothers me that family members I am close to do not understand my new values” and “It bothers me when people pressure me to assimilate (or blend in)”), with higher scores indicating greater acculturative stress. The SAFE has demonstrated strong reliability and been used with different immigrant and later generation populations (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Kia-Keating and Tsai2011; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015; Mena et al., Reference Mena, Padilla and Maldonado1987; Shattell et al., Reference Shattell, Smith, Quinlan-Colwell and Villalba2008). Internal reliability in the current sample was 0.88.

Discrimination was assessed at the 25-week prenatal visit with Williams’ Major and Everyday Discrimination Scales (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Yu, Jackson and Anderson2007). The Major Experiences of Discrimination scale asks participants if they have experienced unfair treatment as it pertains to nine different situations (e.g., ever been unfairly fired, stopped by the police, and so forth). The number of situations participants endorse are summed for a total score. The Everyday Discrimination Scale asks participants how often in their day-to-day life they have experienced discriminatory treatment in 10 contexts, such as being treated with less courtesy than others or followed around in stores (never, once, two or three times, four or more times). The number of times reported is summed for a total score. Both scales have demonstrated construct validity (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Kamarck and Shiffman2004).

Resilience-promoting factors

Community cohesion was assessed at the 25-week prenatal visit with 12 statements from the Social Ties Scale (Cutrona et al., Reference Cutrona, Russell, Hessling, Adama Brown and Murry2000) referring to different types of community support which participants indicated as either true or false (e.g., neighbors get together to deal with community problems, neighbors help and look out for one another). Endorsed items were summed for a total score. This scale has demonstrated adequate reliability in previous research (Cutrona et al., Reference Cutrona, Russell, Hessling, Adama Brown and Murry2000) and had an alpha value of 0.86 in the current study.

Social support also was measured at the 25-week visit with the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SS; Sherbourne & Stewart, Reference Sherbourne and Stewart1991). The MOS-SS consists of 19 items asking about tangible support, positive social interaction, affection, and emotional/informational support. This scale has been used extensively and demonstrates strong reliability (Racine, Madigan, et al., Reference Racine, Madigan, Plamondon, Hetherington, Mcdonald and Tough2018; Sherbourne & Stewart, Reference Sherbourne and Stewart1991). The current study uses a standardized total score, and internal reliability was .98.

Communalism was assessed at the 35-week prenatal visit with a 28-item scale developed by Abdou et al. (Reference Abdou, Dunkel Schetter, Campos, Hilmert, Dominguez, Hobel, Glynn and Sandman2010) from two well-established scales assessing familism and communalism. Participants responded to items such as “I owe it to my parents to do well in life” or “I would take time off from work to visit a sick friend” on a 4-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Items are summed for a total score. The scale has demonstrated good reliability with pregnant women (Abdou et al., Reference Abdou, Dunkel Schetter, Campos, Hilmert, Dominguez, Hobel, Glynn and Sandman2010) and had an alpha value of 0.84 in the current study.

Parenting self-efficacy was collected at 6 months postpartum with the Maternal Self-Efficacy in the Nurturing Role Questionnaire (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Bryan, Huffman and Del Carmen1989). The questionnaire consists of 16 items on a 7-point Likert scale asking mothers’ how representative they feel different statements are of their parenting experience. Example items include, “I am concerned that my patience with my baby is limited” and “I trust my feelings and intuitions about taking care of my baby.” Items are summed for a total score. This scale has previously demonstrated adequate test-retest reliability and internal consistency (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Bryan, Huffman and Del Carmen1989; Porter & Hsu, Reference Porter and Hsu2003) and had internal reliability of 0.84 in the current study.

Infant temperament

Infant Negative Emotionality at 12 months was assessed with the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ; Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003), a 191-item measure that has been used extensively in developmental research and demonstrates good reliability and validity (Goldsmith & Campos, Reference Goldsmith and Campos1990; Worobey & Blajda, Reference Worobey and Blajda1989). In order to reduce maternal reporting bias, questions assess the infant’s concrete behaviors in clearly defined situations, for example, “During a peek-a-boo game, how often did the baby smile?” and “How often during the last week did the baby startle to a sudden or loud noise?” Individual item responses can range from 1 “never” to 7 “always.” The questionnaire items map onto three primary temperament dimensions: Negative Emotionality, Surgency/Extraversion and Orienting/Regulation. The Negative Emotionality dimension, the focus of this investigation, is comprised of four subscales: Sadness, Fear, Falling Reactivity, and Distress to Limitations. Internal reliability of this dimension in the current study was 0.92.

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses included examination of sample demographics, data distributions, bivariate associations, and levels of sociocultural stressors and resilience-promoting factors by race/ethnicity. To select model covariates, we examined demographic variables with prior theoretical or empirical support for association with infant temperament with bivariate correlations, including biological sex at birth, GAB, household income, parental cohabitation, birth order, maternal nativity status, and maternal education. All variables significantly associated (p < .05) with temperament were included in subsequent models. The amount of missing data averaged less than 4% across all variables included in analyses, and Little’s MCAR test indicated there was no systematic pattern of missing values (χ 2(52) = 55.36, p = .35).

Hierarchical linear regression was utilized to first assess the impact of sociocultural stressors on infant negative emotionality above and beyond covariates. Only sociocultural stressors that showed bivariate associations with negative emotionality were included in regression models. Promotive (main) and protective (interaction) effects of resilience-promoting factors were subsequently tested in a third step (community cohesion, social support, communalism, and parenting self-efficacy). The same four models were repeated with each sociocultural stressor.

Lastly, because a number of DoHAD findings have suggested that vulnerabilities to prenatal stress are sex-differentiated (Braithwaite et al., Reference Braithwaite, Pickles, Sharp, Glover, O’Donnell, Tibu and Hill2017; Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2021; Glynn & Sandman, Reference Glynn and Sandman2012; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Swales, Garcia, Driver and Davis2019; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Schutze, Henley, Pennell, Straker and Smith2021; Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Nentin, Bosquet Enlow, Hacker, Pollas, Coull and Wright2019; Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Glynn and Davis2013; Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Class, Glynn and Davis2015; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Hill, Hellier and Pickles2015), we tested the interaction of stressor X sex in a fourth step. All continuous variables contributing to interaction terms were centered prior to analysis.

Hayes’ (Reference Hayes2018) PROCESS macro for SPSS was used to plot and probe significant interactions at the 16th and 84th percentiles of the predictor variable (indicating low and high levels of the predictor; Hayes, Reference Hayes2018), and the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of the moderator (indicating low, moderate, and high levels of the moderator). The Johnson-Neyman technique was utilized to define regions of significance (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018).

Results

Descriptive information

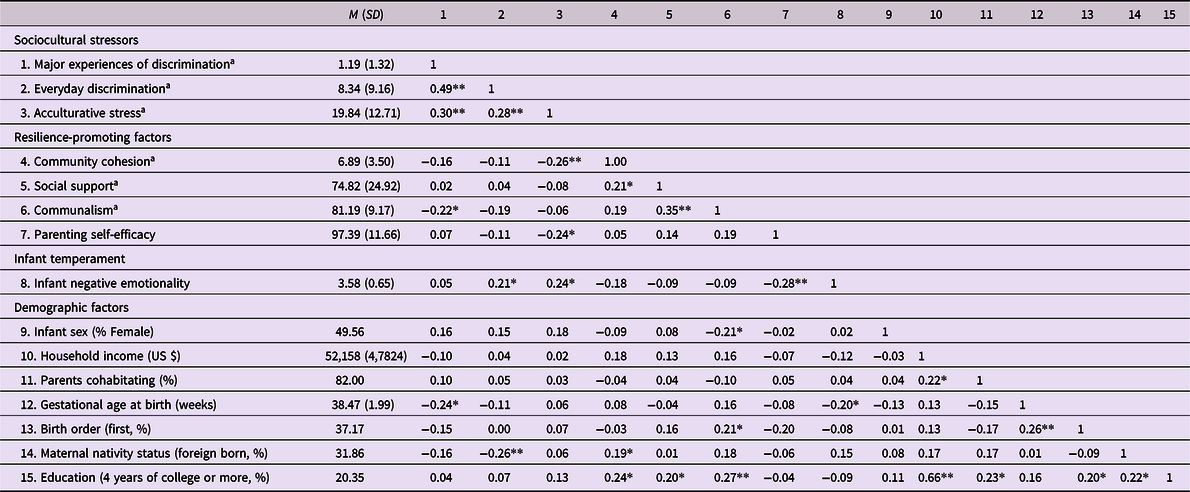

Table 2 displays means and bivariate associations of study variables. All sociocultural stressors were positively associated with one another. Among resilience-promoting factors, social support was associated with both community cohesion and communalism. Everyday discrimination and acculturative were related to more negative emotionality, while parenting self-efficacy and GAB were related to less negative emotionality.

Table 2. Means and intercorrelations of sociocultural stressors, resilience-promoting factors, negative emotionality, and demographic factors

Note. aMeasure was assessed prenatally. *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01.

Participants’ average levels of sociocultural stressors and resilience-promoting factors are presented by race/ethnicity in Table 3. Although differences across race/ethnicity were not tested statistically, descriptively Black and Multiethnic participants experienced the greatest amount of discrimination on average, while Asian American participants had the highest levels of acculturative stress. Black participants reported the highest average levels of all resilience-promoting factors.

Table 3. Means of sociocultural stressors and resilience-promoting factors by race/ethnicity

Note. Values presented are sample means, with standard deviation in parentheses. Due to small sample sizes, statistical differences were not tested. aMeasure was assessed prenatally.

Risk and resilience analyses

Both everyday discrimination and acculturative stress (assessed prenatally) significantly predicted infant negative emotionality after adjusting for GAB (see Step 1 in Tables 4–5 and Figure 1). When entered into the linear regression model with everyday discrimination, parenting self-efficacy had a promotive/main effect on negative emotionality such that higher levels of parenting self-efficacy were associated with less infant negative emotionality (see Table 4, Figure 1a). When entered into the model with acculturative stress, parenting self-efficacy had a significant protective/interaction effect, with moderate and higher levels of parenting self-efficacy buffering the relation between acculturative stress and infant negative emotionality (see Table 5, Figure 1b; Conditional Effects: Low PSE: t = 3.40, p < .001; Moderate PSE: t = 1.21. p = .23; High PSE: t = −0.57, p = .57). The Johnson−Neyman Regions of Significance test indicated the relation between acculturative stress and negative emotionality was no longer statistically significant when level of parenting self-efficacy was above 97.02 (approximately 43rd percentile in the current sample). As parenting self-efficacy levels increased beyond 97, the relation between acculturative stress and negative emotionality continued to decrease in strength. No other resilience factors (community cohesion, social support, or communalism) were found to have significant main or interaction effects on negative emotionality in models with acculturative stress or everyday discrimination (six models in total). These results are provided in the Supplementary Material (see Supplementary Tables 4–7).

Figure 1. Parenting self-efficacy functions as a resilience-promoting factor in the context of prenatally assessed maternal sociocultural stressors (a, everyday discrimination, b, acculturative stress) and infant negative emotionality. Note. Low, moderate, and high represent the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles of the predictor and moderator variables.

Table 4. Main and interaction effects of discrimination and parenting self-efficacy on negative emotionality

Note. Model run with the inclusion of household income, parental cohabitation, infant sex, and parity did not substantively change results. aMeasure was assessed prenatally.

Table 5. Main and interaction effects of acculturative stress and parenting self-efficacy on negative emotionality

Note. Model run with the inclusion of household income, parental cohabitation, infant sex, and parity did not substantively change results. aMeasure was assessed prenatally.

Results testing the interaction of sex and sociocultural stressors are reported in the Supplementary Material. The interaction of sex and acculturative stress during pregnancy reached statistical significance in some (see Supplementary Tables 5, 7, 9), but not all models. Plotting this interaction suggests the association between acculturative stress and negative emotionality may be stronger for girls than boys (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The relation between prenatally assessed acculturative stress and negative emotionality is stronger for girls. Note. Low and high acculturative stress represent the 16th and 84th percentiles. Model adjusts for gestational age at birth.

Discussion

The far reaching effects of mental health disorders in childhood are disproportionately felt by youth of color (Alegria et al., Reference Alegria, Vallas and Pumariega2010; Marrast et al., Reference Marrast, Himmelstein and Woolhandler2016), emphasizing the importance of understanding and ultimately intervening with early antecedents and precipitants of childhood mental health challenges. Although it is established that preconception and prenatal stress impacts offspring mental health (Graignic-Philippe et al., Reference Graignic-Philippe, Dayan, Chokron, Jacquet and Tordjman2014; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Kim, Shin, Yoo, Lee and Cho2014; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer, Hoyer, Roseboom, Räikkönen, King and Schwab2017), to date stressors emphasized by the Integrative Model as critical for understanding development in populations of color, including discrimination and acculturative stress (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Lamberty, Jenkins, Pipes McAdoo, Crnic, Hanna Wasik and Vázquez García1996), have been understudied in this context. Further, questions remain unanswered about which maternal factors promote infant resilience to preconception and prenatal adversity exposure (Liu & Glynn, Reference Liu and Glynn2021). Results of the current study add empirical evidence to these existing research gaps. Specifically, we found that maternal experiences of acculturative stress and everyday discrimination, assessed prenatally, predicted infants’ greater negative emotionality at 12 months of age, but that mothers’ parenting self-efficacy at 6 months of age counteracted these effects.

Our findings have implications for future study as well as prevention and intervention. Accumulating research has shown that acculturative stress and discrimination are harmful to one’s health (Bekteshi & van Hook, Reference Bekteshi and van Hook2015; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015; Paradies et al., Reference Paradies, Ben, Denson, Elias, Priest, Pieterse, Gupta, Kelaher and Gee2015; Revollo et al., Reference Revollo, Qureshi, Collazos, Valero and Casas2011; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Lawrence and Davis2019). Here, we see evidence that they may also be risk factors for mental health of the next generation. Notably we did not find an association between major events of discrimination and infant negative emotionality, consistent with previous research findings that more chronic, everyday discrimination may be more harmful to health and development (Ayalon & Gum, Reference Ayalon and Gum2011; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Culhane, Webb, Coyne, Hogan, Mathew and Elo2010; Wheaton et al., Reference Wheaton, Thomas, Roman and Abdou2018). Therefore, the development of, and research on, policies and programs to reduce maternal stress exposure must consider acculturative stress and chronic discrimination.

Because we found associations between parenting self-efficacy and lower levels of infant negative emotionality, and did not find links of the same magnitude for communalism, social support, or community cohesion, our results also indicate the potential of intervention and prevention programs that enhance parenting self-efficacy to promote child emotional health and reduce later mental health challenges. One method for achieving this goal could involve brief parenting support and parenting skill sessions embedded into pediatric well-child visits (Weisleder et al., Reference Weisleder, Cates, Dreyer, Johnson, Huberman, Seery, Canfield and Mendelsohn2016) or home visiting programs (Granado-Villar et al., Reference Granado-Villar, Boulter, Brown, Gaines, Gitterman, Gorski, Katcher, Kraft, Marino and Sokal-Gutierrez2009) throughout a child’s first year of life. There are a number of brief parenting interventions, such as Triple P, that have already been shown to improve parenting self-efficacy (Gilkerson et al., Reference Gilkerson, Burkhardt, Katch and Hans2020; Tully & Hunt, Reference Tully and Hunt2016).

The current study also highlights some priority areas for future research. More studies are needed to replicate and expand the links between prenatal sociocultural stress and infant negative emotionality, including through the study of additional indicators of emotional and cognitive development, and later mental health outcomes. Notably, analyses found some evidence to suggest that the association between acculturative stress and negative emotionality differed by sex. Specifically, in some models, the effect appeared stronger for girls than boys. Future research examining this moderation by sex with larger sample sizes could improve understanding of this potential interaction, but these results do align with those of previous researchers (Braithwaite et al., Reference Braithwaite, Pickles, Sharp, Glover, O’Donnell, Tibu and Hill2017; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Swales, Garcia, Driver and Davis2019; Sandman et al., Reference Sandman, Glynn and Davis2013). Evidence suggests mechanisms behind these results may include differential HPA axis and placental responses to stress based on fetal sex (Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, Swales, Garcia, Driver and Davis2019).

Another important observation from this study was the presence of statistically significant associations among all of the sociocultural stressors examined – suggesting that women of color face multiple co-occurring stressors related to their race/ethnicity and social position in a society built on structural racism (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Krieger, Agénor, Graves, Linos and Bassett2017). For this reason, we did not examine specific types of discrimination, such as sexism and racism, but rather assessed the impact of any form of chronic discrimination on birth outcomes. However, future research that considers distinctive sources of discrimination and other stressors, including structural racism, is necessary.

Next steps for this work should also focus on identifying the psychobiological mechanisms of intergenerational transmission of sociocultural stress from mother to child during pregnancy. One possible mediating factor is earlier GAB, which was related to infant negative emotionality in the current study, and has previously been linked to maternal experiences of prenatal discrimination (although we did not see associations with acculturative stress or everyday discrimination; Alhusen et al., Reference Alhusen, Bower, Epstein and Sharps2016; Christian, Reference Christian2020). Maternal distress stemming from sociocultural stress also could be an intermediary factor; this hypothesis is supported by research findings that discrimination and acculturative stress are linked to depressive symptoms (Canady et al., Reference Canady, Bullen, Holzman, Broman and Tian2008; D’Anna-Hernandez et al., Reference D’Anna-Hernandez, Aleman and Flores2015) and infant temperament (see Supplemental Table S10).

In this study, community cohesion, communalism, and social support did not show statistically significant resilience-promoting effects. However, continuing to test these factors is important because their effectiveness may be dependent on certain contextual factors, such as cultural background or acculturation level. It is important that future research statistically test these differences in larger samples, as it may guide understanding of what forms of resilience and protective factors are more likely accessible within communities of color.

There also are limitations to the current research that are important to note. First, the sample was limited in terms of its racial/ethnic diversity, with the majority of participants (69%) being Latinx/Hispanic. Although discrimination is a universal experience for all populations of color, these experiences are not distributed equally or uniformly across populations (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Perez, Malik Boykin and Mendoza-Denton2019). Research on larger samples that allows for the statistical testing of these differences, as well as the examination of relations between sociocultural stressors and infant outcomes separately for mothers and infants of various race/ethnicities, could help to elucidate if these stressors are more salient for some populations versus others, and why.

Second, while our conclusion that parenting self-efficacy may have a positive impact on subsequent infant negative emotionality is heightened by distal and sequential separation of the measures (6 and 12 months) it is important to acknowledge that these findings are maternal report and correlational. As such, there is a possibility that parenting self-efficacy may be enhanced when parenting an infant with an easier temperament. However, prior research findings suggest that parenting self-efficacy prospectively predicts infant negative temperament, but not the other way around (Verhage et al., Reference Verhage, Oosterman and Schuengel2013). It is also conceivable that these relations may be influenced by maternal bias, although a recent study of 935 mothers found configural, metric, and scalar invariance between mothers with and without a lifetime history of depression across dimensions of maternal-rated child temperament, leading authors to conclude that maternal report of youth temperament is not biased by maternal mental illness (Olino et al., Reference Olino, Guerra-Guzman, Hayden and Klein2020). The likelihood of bias is also reduced by the IBQ’s specific measure design to avoid maternal reporting bias through asking questions about infants’ concrete behavior in specific situations. Still, future research that confirms the relation between sociocultural stress, parenting self-efficacy, and infant temperament as measured with independent observers or with behavioral measures would strengthen the validity the current findings. Lastly, this study did not include postnatal measures of discrimination and acculturative stress, thus limiting our understanding of whether preconception or prenatal sociocultural stress has a distinctive impact on infant temperament over and above postnatal sociocultural stress. Future research that includes these measures at both pre- and postnatal timepoints can assist in understanding how timing matters for stress transmission.

Despite this study’s limitations, the implications of our findings are clear. In the field of maternal and child health, several truths must be acknowledged. First, women of color face more stressors compared to their White counterparts because of societal systems that marginalize people of color, and second, this stress exposure translates to health risk for offspring, potentially perpetuating health disparities across generations. This recognition is particularly important in the current moment, as we are presently experiencing a unique historical time of societal upheaval and threat against communities of color. The years leading up to 2022 have been marked by rising national rates of White nationalism and White supremacy, racially motivated hate crimes, anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies, and racist police brutality (Boyd, Krieger, et al., Reference Boyd, Krieger and Jones2020; Seaton et al., Reference Seaton, Gee, Neblett and Spanierman2018). The year 2020 was defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, which illuminated and exacerbated economic and health inequities across racial lines and exposed the deeply embedded nature of racism in the U.S (Boyd, Krieger, et al., Reference Boyd, Krieger and Jones2020; Liu & Modir, Reference Liu and Modir2020; Seaton et al., Reference Seaton, Gee, Neblett and Spanierman2018). The consequences of COVID-19 for communities of color, in conjunction with continued police killings of unarmed Black people and the massive protests that followed, has led many cities and organizations across the country to make a long overdue declaration: that racism is a public health crisis (Krieger, Reference Krieger2020). Findings of the current study and others suggest that heightening racism across the country will have a long-lasting impact on maternal and infant health, yet COVID-19 is ironically likely to shift attention away from these areas in the short-term, due to urgent competing health priorities (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Briana, Di Renzo, Modi, Bustreo, Conti, Malamitsi-Puchner and Hanson2020).

Therefore, there is a need for research, policy, and practice that pushes for further understanding of relations between prenatal sociocultural stress and infant outcomes, that reduces stress exposure, and that promotes resilience in this context. Having a comprehensive understanding of the role of structural racism in health disparities is critical for anyone engaging in this work, and advocates have called for researcher and practitioner training in topics such as structural competency, cultural humility, structural determinants of disease, defining race as a social and power construct, and institutional inequities as a root cause of injustice (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Krieger, Agénor, Graves, Linos and Bassett2017; Barkley et al., Reference Barkley, Kodjo, West, Vo, Chulani, Svetaz, Sylvester, Kaul and Sanchez2013; Cerdeña et al., Reference Cerdeña, Plaisime and Tsai2020; Metzl et al., Reference Metzl, Petty and Olowojoba2018; Metzl & Hansen, Reference Metzl and Hansen2014). Lastly, while interventions focused on prenatal health and child and family well-being are needed and important, true primary prevention to achieve health equity necessitates the creation of policies and systems that no longer systematically undermine the health of people of color (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2020).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422000141.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their heartfelt thanks to the families in this study for their continued participation. We also would like to thank the entire team at Chapman University’s Early Human and Lifespan Development Program, and in particular Natasha Bailey, Kendra Leak, and Gage Peterson for their assistance on this project. Your dedication and excellent work are greatly appreciated.

Funding statement

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (grant number MH096889).

Conflicts of interest

None.