Overview

Conventional wisdom holds that the Framers of the Constitution were more concerned with the executive and legislative branches of government than the judicial branch. Supreme Court historian Julius Goebel Jr. explains:

The judiciary was subjected to much less critical working over than the other departments of government … it is difficult to divest oneself of the impression that … provision for a national judiciary was a matter of theoretical compulsion rather than of practical necessity (1971:205–6).

This conception of the judiciary as an institution driven by the theoretical rather than by the purposive has flourished and expanded. The early Court is considered underdeveloped with little jurisdiction and no clear national role, underdefined with inadequate resources and few subordinate courts. The conventional description is that the Court has gone through three distinct deliberative eras (Reference SchwartzSchwartz 1993:378–80; Reference Kernell and JacobsonKernell & Jacobson 2006:349–54). After a fallow decade (1789–1801), the Court first addressed questions of nation-to-state relations. Second, the Court addressed the limitations of government regulation of the economy. Third, the Court engaged issues of civil rights and liberties. Chief Justice John Marshall biographer Reference SmithJean Edward Smith succinctly characterizes the view of the early/pre-Marshall Court: “During this period, the nature of the Court's authority was vague and its caseload was light” (1996:2–3).

In the main, judicial scholars claim the Court only became an important institution after the arrival of Chief Justice Marshall and his assertion of judicial review (Reference GerberGerber 1998:2). The pre-Marshall Court has been described as a “relatively feeble institution” (Reference Haskins and JohnsonHaskins & Johnson 1981:7) notable for its “lack of significance” (Reference SchwartzSchwartz 1993:33). In addition to a dearth of reported cases (Reference GerberGerber 1998:3), the early Court also has been dismissed because of the initial difficulties in finding men willing to serve and even because of the absence of a separate building to house the Court (Reference SwisherSwisher 1943:98–101; Reference RodellRodell 1955:3–72). In an often quoted passage, Reference McCloskeyMcCloskey makes the case with rhetorical flourish:

It is hard for a student of judicial review to avoid the feeling that American constitutional history from 1789 to 1801 was marking time. The great shadow of John Marshall, who became Chief Justice in the latter year, falls across our understanding of that first decade; and it has therefore the quality of a play's opening moments with minor characters exchanging trivialities while they and the audience await the appearance of the star (1994:19).

Although most scholars have dismissed the importance of the early Court, there is a limited body of literature that considers its impact. Reference CorwinCorwin once suggested that although the early Court had “fallen into something like obscurity” it nevertheless had prepared the way for much of Chief Justice Marshall's “most striking decisions” (1919:17–8). Unfortunately, throughout his distinguished career, Corwin never returned to or expanded this early insight. More recently, a small but growing group of scholars have given measured consideration to the pre-Marshall Court. Reference GerberGerber explains the purpose of Seriatim, a collection of essays regarding the members of the pre-Marshall Court, as in part “to dispel the myth that the early Court became significant only when Marshall arrived” (1998:20). Reference CastoCasto asserts that the primary objective of the early Court was to “bolster and consolidate the new federal government” (1995:213). Casto argues:

The Founders envisioned the federal courts as national security courts, and the Supreme Court's first decade is largely a story of … grappling with important issues affecting the nation's security … in addition, the major recurring theme of the decade was the Justices' on-going efforts to assist … in evolving a stable relationship with the European powers … (1995:71).

With Reference CastoCasto (1995) and Reference GerberGerber (1998), I reject the conventional wisdom about the irrelevance of the early Court. I focus on the institutional role of the Court. I argue that a significant rationale for the jurisdiction and design of the Court was to establish a credible commitment to uphold trade agreements and resolve trade disputes with other nations. Of course, the Framers' view of the purpose of the Court was not all-encompassing or conceptually complete. The conventional wisdom focuses in part on the ambiguity in Article III of the U.S. Constitution—including the inherent ambiguity in establishing appellate jurisdiction at some undetermined later date. Clearly, the Framers' collective view of the theory of judicial power was subject to future development. They may not have agreed on the role of the Court in every aspect of governance, but they clearly concurred on the role of the Court in trade. The argument here is not that the conventional wisdom is wrong; but rather, that it is incomplete.

As an emerging nation, the United States faced a hostile world. Typically, justifications for war in this time period fell under the ambit of violations of the law of nations.Footnote 1 Generally these disputes were tied to trade and, as a corollary, navigation (Reference Higgins and ColombosHiggins & Colombos 1951:506–8; Reference Jefferson and PetersonJefferson 1984:818–20, 1090–5). Disputes between individuals and nations, also normally tied to trade, were common pretexts for war.Footnote 2 This belligerent world was even more perilous for the new nation because of the absence of a standing army or a ready navy.Footnote 3 Further, the Framers were suspicious of both England and France and anxious to avoid being embroiled in their persistent conflicts.Footnote 4 The dispensation and ownership of the Spanish territories of Florida and Louisiana also were cause for concern (Reference BanningBanning 1995:18–9; Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:265–8; Reference Jefferson and PetersonJefferson 1984:1104). Indeed, foreign affairs and the threat of war became one of the “primary themes” of the campaign for ratification of the Constitution (Reference MarksMarks 1971:469).

Accordingly, one of the more difficult tasks facing the new nation was to structure institutional mechanisms to deprive hostile nations of justifications for aggression. Because the country was formed through a rejection of royal rule,Footnote 5 it unavoidably also rejected the law of nations.Footnote 6 That is, if the revolutionists did not recognize King George's divine right of rule, other monarchs had no reason to believe the nation's new leaders would recognize any other right of rule. The new nation could not simply demand international recognition from the established nations that saw the revolution as a threat to the system as a whole. The royal right of rule was considered a God-given prerogative of monarchs. The law of nations rested on the mutual recognition of royal peers, all divinely entitled to their posts. By throwing off royal rule and asserting the right to self-rule, the revolutionists called into question the very foundation of government. Since the monarchies were both the subjects and objects of the law of nations—both creating and abiding by the law—a rejection of their right to rule was considered a rejection of the law of nations. Nations under a kingly rule were to be ruled by kings, not by mobs that overthrow the king. The promises of a king to a peer were to be kept as the bond of one messenger of the divine to another. Without divinely justified royal rule, the revolutionists could not make a claim that they—and their nation—could be trusted as a peer. If the revolutionists did not recognize the right of their own king, no other king could expect the proper respect.

The new nation was faced with the economic necessity of engagement in the world economy (Reference BreenBreen 2004; Reference Kernell and JacobsonKernell & Jacobson 2006:41–3). Yet recognition from the monarchs of Europe did not automatically follow from the declaration of independence and successful revolution. Moreover, by rejecting the royal right of rule, the revolutionists lost their claim to appeal to the system of grievance resolution, the varied King's Courts, constructed by the monarchs. Without a mechanism for grievance resolution, trade with the new country was risky and belligerence toward it was acceptable.

In an effort to be recognized at the table of nations, the new nation was forced to construct mechanisms for the resolution of disputes before those disputes led to aggression. A primary purpose of the Court was to provide an avenue of administrative remedy both recognized and deemed legitimate by other nations so that aggrieved nations did not first turn to self-help. Without these avenues of grievance resolution, the new nation could not hope to be viewed by the international community as anything but a rogue state. Important to note, any claimed commitment would only serve as an acceptable path for remedies to the extent that the commitment was deemed credible by those actually or potentially aggrieved.

Credibility is a critical aspect of any commitment because “a promise is not valuable unless its beneficiary believes that it will be kept” (Reference BairdBaird et al. 1994:51). Reference PiersonPierson has succinctly defined “credible commitments” as “the attempt of political actors to create arrangements that facilitate cooperation by lengthening time horizons” (2000:261). The simple concept is that a lengthened time horizon lowers the discount rates—or enhances the political relevance of—the future. North argues that the “major role of institutions in a society is to reduce uncertainty by establishing a stable … structure to human interaction” (1990:6). In other words, reducing the transaction costs and thereby extending the politically relevant time horizon enhances the potential for cooperation and exchange. The institutions in society are “the underlying determinant of the long-run performance of economies” (Reference NorthNorth 1990:107). For both economic and security reasons, then, the Framers sought to design an institutional vehicle to establish the credible commitment necessary for trade as well as the avoidance of belligerence.

The establishment of the Supreme Court as this institutional vehicle of credible commitment was strategically compelling for two reasons. First, the reduction of potential transaction costs enhanced the potential for trade. Second, the existence of a mechanism of dispute resolution reduced the international acceptability of belligerence against the United States. As Knight has explained, “[s]ocial institutions are conceived of as a product of the efforts of some to constrain the actions of others with whom they interact” (1992:19). While Reference KnightKnight (1992) was concerned with the interactions and establishment of institutions within a society, his analysis is no less compelling when considering the interactions and establishment of institutions among societies. In this case, the administrative remedy provided by the Court reduced the acceptability of belligerence among the members of the society of nations.

A discussion of the law of nations at the time of the founding serves as the first step in this consideration. This section addresses the nature and scope of the law of nations as well as its jurisprudential underpinnings, including the law of the sea, trade laws, and the notion of legitimate wars among the members of the international community. I then turn to the juridical intent set forth first under the Articles of Confederation and then solidified in Article III of the Constitution. The intent expressed in both the Articles and the Constitution was the foundation for the judicial barriers to the pretexts for war. The argument is supported further through a consideration of the state ratification debates, selected writings of the Framers and early justices, and the Judiciary Act of 1789. Thereafter, I turn to a review of the cases and controversies confronted by the Supreme Court before Marshall assumed the office of chief justice. The case law shows that the Court rarely dealt with any case or controversy that did not directly involve admiralty or trade disputes between states and other states, foreign nations, or foreign individuals. These are the very types of disputes the judiciary was designed to address, since they might well have led to war.Footnote 7 Critically, the Court's early primary concern under this conceptualization was international relations rather than the relationship between government and the individual. Accordingly, the conventional story of the development of the Court and constitutional jurisprudence remains intact but now has a new opening act. After this institutional and historical analysis, I draw conclusions about the institutional role of the early American judiciary and discuss some implications from the analysis.

The Law of Nations

A public war is undertaken justly in so far as judicial recourse is lacking …

A private war is undertaken justly in so far as judicial recourse is lacking …

(Hugo Grotius, De Iure Praedae Commentarius: Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty, A Translation of the Original Manuscript of 1604, 1964:95, 103)

The international legal system is generally considered to have emerged with the modern state, although the origins of many of the rules and principles of the law of nations can be traced to ancient Rome and Greece (Reference Jessup and DeakJessup & Deak 1935:3–4). Since the system contemplates a regulation of relationships among states, there could be no system without states. Although the emergence of the nation-state began centuries earlier, the origins of the international legal system can be linked to the 1625 publication of Grotius's De Jure belli ac pacis (The Law of War and Peace) and the resolution of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 (the Peace of Westphalia) (Reference Jessup and DeakJessup & Deak 1935:4, 8–11). Important to note, Grotius's De Jure belli ac pacis is the most renowned of three related publications. The other publications, Mare Liberum (Freedom of the Seas) and De Jure Praedae (The Law of Prize) specifically address freedom of navigation for purposes of trade and the appropriate right of maritime seizure during war (Reference Grotius and WilliamsGrotius 1964:xiv–xvii). By the end of the eighteenth century, the law of nations was little more than the “common consent of the nations” (Reference MahanMahan 1892:284). Reference SorelSorel argues that this concept was ephemeral and could only be known “through the declamations of publicists and its violations by the Governments” (1891:65, note 7). The “common consent” of the nations was seldom reached. Few rules were universally accepted, and none covered all contingencies (Reference Phillips and ReedePhillips & Reede 1936:11).

The European powers in general and Great Britain in particular perceived the revolutionary wars in the United States and France as abrogations of both the established regal rights of rule and the law of nations (Reference Phillips and ReedePhillips & Reede 1936:4–9). Regarding the revolutions, Lord Chancellor Eldon argued in the House of Lords:

It is vain to refer to the law of nations for any authority on this subject, in the unprecedented circumstances in which this country is now placed. What usually passes by that name is merely a collection of the dicta of wise men who have devoted themselves to the subject in different ages, applied to the circumstances of the world at the period in which they wrote … but none having the least resemblance to the circumstances in which this country is now placed …

(Reference Phillips and ReedePhillips & Reede 1936:11).From the perspective of the European powers, the revolutionists recognized “no law but that of reason and the Rights of Man” (Reference Phillips and ReedePhillips & Reede 1936:10–11). By rejecting the royal right of rule, the revolutionists lost their claim to appeal to the system constructed by royal rulers for grievance resolution. In response, those nations that abided by the law of nations were free to violate it regarding the revolutionists.

The task of the American Founders was all the more complicated because of the uncertain parameters of the law of nations at the time. Indeed, arguably the only important dictates of the law of nations certain at the time of the war for independence were the Doctrine of Neutrality and the corollary Laws of Prize. The Doctrine of Neutrality holds that neutral states (those states not party to the conflict), are free to continue their normal trade with either or both belligerent states (Reference Higgins and ColombosHiggins & Colombos 1951:458–74). The Laws of Prize dictate that a belligerent may seize only contraband, those items deemed helpful to the war effort, from a neutral (Reference Phillips and ReedePhillips & Reede 1936:11).

Despite these broadly accepted rules of the law of nations,Footnote 8 from the revolution forward, England refused to grant immunity from search and seizure to neutral trade with France (Reference Higgins and ColombosHiggins & Colombos 1951:465). Moreover, Jefferson took exception to the law of Prize and explained why he believed the underlying jurisprudence was misguided:

We believe the practice of seizing what is called contraband of war, is an abusive practice, not founded in natural right. War between two nations cannot diminish the rights of the rest of the world remaining at peace. The doctrine that the rights of nations remaining quietly under the exercise of moral & social duties, are to give way to the convenience of those who prefer plundering & murdering one another is a monstrous doctrine; and ought to yield to the more rational law, that “the wrongs which two nations endeavor to inflict on each other must not infringe on the rights or conveniences of those remaining at peace”…

(Jefferson 1801, cited in Reference Jefferson and PetersonJefferson 1984:1092–3).As the United States continued to suffer the loss of goods and commerce, Jefferson lamented, “[i]t would have been a source, fellow citizens, of much gratification, if our last communications from Europe had enabled me to inform you that the belligerent nations, whose disregard of neutral rights has been so destructive to our commerce, had been awakened to the duty and true policy of revoking their unrighteous edicts …” (Jefferson 1801, cited in Reference Jefferson and PetersonJefferson 1984:543).

The United States was a vulnerable target both because its defenses were weak and because there was no reason for other nations to be confident that its rebel government could make credible commitments to other nations. Although ambassadors had been sent abroad and the rebellion had produced the confederation, the financial straits of the national government combined with nonpayment of debts by the states meant that, internationally, the new country still could not be trusted in matters of trade. The Constitutional Convention was called to redress the failings of the confederation. These problems included a poor international reputation and an inability of international trading partners to make claims for damages in a nonpolitical arena. It was the plan of the Founders that foreign powers should be able to seek and receive redress for alleged violations of the law of nations in federal courts in the United States.

The Historical Context of the New Judiciary

Judicial Power Under the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution

The capital and leading object of the constitution was to leave with the states all authorities which respected their own citizens only, and to transfer to the United States those which respected citizens of foreign or Other states: to make us several as to our selves, but one as to all others.

(Thomas Jefferson 1801, cited in Writings, 1984:1475)The member states of the nascent United States confederated at the outset to secure independence and mutual security (Reference DoughertyDougherty 2001:17). However, within 10 years the new nation experienced open rebellion in Massachusetts, heightened interstate rivalry, and a multiplicity of trade disputes (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:107). As shown here, the Framers perceived the need to develop a legitimate forum to adjudicate trade matters as a critical issue. In response not only to the well-known list of crises but also to address the concern about trade disputes, the representatives of the member states convened in Philadelphia in May 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation (Reference GoebelGoebel 1971:198).

The Convention of 1787 was called to order by Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph. Governor Randolph first observed that the Confederation had “fulfilled none of the objectives for which it was framed” (McHenry 1787, cited in Reference SteinerSteiner 1906:596). Governor Randolph began with his view of the major defects in the Confederation. The first “imbecility” of the Confederation was:

It does not provide against foreign invasion. If a state acts against a foreign power contrary to the laws of nations or violates a treaty, it cannot punish that State, or compel its obedience to the treaty. It can only leave the offending state to the operations of the offended power. It therefore cannot prevent war. If the rights of an ambassador be invaded by any citizen it is only in a few States that any laws exist to punish the offender. A state may encroach on foreign possessions in its neighborhood and Congress cannot prevent it …

(McHenry 1787, cited in Reference SteinerSteiner 1906:596).His concern about the inability of the Confederation to prevent war was compounded by its now well-known inability to fund a war effort. The overarching concern for national security also became a central issue in persuading the populace to support the new Constitution (Reference MarksMarks 1971). Indeed, 25 of the first 36 Federalist Papers concerned the lack of national security (Reference MarksMarks 1971:446).Footnote 9 The New York Journal supported the ratification of the Constitution largely because:

Wars have been, and … will continue to be frequent. A war has generally happened among the European nations as often as once in twelve or fifteen years for a century past; and for more than a third of this period, the English, French, and Spaniards have been in a state of war. The territories of these nations border upon our country. England is at heart inimical to us; Spain is jealous … It would be no strange thing if within ten years the injustice of England or Spain should force us into a war; it would be strange if it should not within fifteen or twenty years

(editorial, New York Journal, 29 March 1787, cited in Reference MarksMarks 1971:451).The second defect discussed by Governor Randolph as he opened the convention was:

2. It does not secure harmony to the States.

It cannot preserve the particular states against seditions within themselves or combinations against each other … No provision [exists] to prevent the States breaking out into war.

One State may as it were underbid another by duties, and thus keep up a State of war …

(McHenry 1787, cited in Reference SteinerSteiner 1906:596).Although devoid of a mechanism of enforcement, the Articles prohibited the member states from a variety of activities that could imperil the Union. Among these prohibited activities were engaging in foreign relations of any sort, whether waging war or brokering peace through treaties; the resolution of cross-state disputes, whether arising from trade or territory; and any interference with tariffs or duties.Footnote 10 The Articles gave exclusive jurisdiction over these issues to Congress but created no capacity to sanction (e.g., Article VIII, Articles of Confederation). When the new Constitution was finalized, Article III provided the framework and parameters of the federal judiciary. The new Constitution preserved much of the juridical sentiment of the Articles of Confederation.

As Reference ShapiroShapiro points out, the “basic social logic, or perceived legitimacy, of courts, rests on the mutual consent of two persons in conflict to refer that conflict to a third for resolution” (1981:36). In an effort to create that “third person,” tribunal power was taken from the Congress and deposited in an independent judicial branch. Although the new administrative arrangement contemplated independence for the judiciary, the focus of juridical concern remained the same. The new Constitution provided:

Article III

Section 1. The judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish …

Section 2. The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; - to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, or other public ministers and Consuls; - to all cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; - to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; - to Controversies between two or more States; - between a State and Citizens of another State; - between Citizens of different States; - between citizens of the same state claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens, or Subjects.

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, or other Public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction …

The newly constituted judiciary maintained the juridical focus on a limited number of issues. In general, the disputes over which original jurisdiction was granted involved those controversies among states and those controversies between states and foreign individuals and powers.

The State Ratification Debates

The ratification debates regarding the judiciary further illuminate the institutional role of the Court from the perspective of those who created it.Footnote 11 During the Virginia debates, Marshall is reported as taking the following position:

Suppose, says he, in such a suit, a foreign state is cast, will she be bound by the decision? If foreign states brought a suit against the Commonwealth of Virginia, would she not be barred from the claim if the Federal Judiciary thought it unjust? The previous consent of the parties is necessary. And, as the federal judiciary will decide, each party will acquiesce. It will be the means of preventing disputes with foreign nations

(The Debate on the Constitution 1993:722).Thus Marshall conceived of the Court as providing a disinterested third party for dispute resolution—especially disputes with foreign nations. During the Virginia debates, William R. Davee also agreed with Marshall. Davee argued,

It is another principle which I imagine will not be controverted, that the general judiciary ought to be competent to the decisions of all questions which involve the general welfare or the peace of the union. It was necessary that treaties should operate as law upon individuals. They ought to be binding upon us the moment they are made. They involve in their nature, not only our own rights, but those of foreigners. If the rights of foreigners were left to be ultimately decided by thirteen distinct judiciaries, there would be unjust and contradictory decisions. If our courts of justice did not decide in favor of foreign citizens and subjects, when they ought, it might involve the whole union in a war

(The Debate on the Constitution 1993:894).James Madison agreed with the views of Marshall and Davee. He explained the general principle behind the original jurisdiction of the judiciary as:

to prevent all occasions of having disputes with foreign powers, to prevent disputes between different states … As our intercourse with foreign nations will be affected by decisions of this kind, they ought to be uniform. This can only be done by giving the federal judiciary exclusive jurisdiction. Controversies affecting the interests of the United States ought to be determined by their own judiciary, and not be left to partial, local tribunals

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:1409).Governor Randolph reiterated Madison's argument by suggesting that the Court's purpose was:

to perpetuate harmony between us and foreign powers. The general government having the superintendency of the general safety, ought to be the judges of how the United States can be most efficiently secured and guarded against controversies with foreign nations. I presume therefore that the treaties and cases affecting ambassadors and other public ministers, and consuls, and all those concerning foreigners, will not be considered as improper subjects for the federal judiciary. … Cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction cannot with out propriety, be vested in particular state courts. As our national tranquility and reputation, and intercourse with foreign nations may be affected by admiralty decisions; as they ought therefore to be uniform; as there can be no uniformity in thirteen distinct, independent jurisdictions, - this jurisdiction ought to be in the federal judiciary …

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:1451–2).Madison succinctly put his concern for foreign trade and the ability of those foreign interests to obtain a fair adjudication this way: “[w]e well know, sir, that foreigners cannot get justice done them in these [state] courts, and this has prevented many wealthy gentlemen from trading or residing among us, there are also many public debtors, who have escaped from justice for want of such a method as has been pointed out in the plan on the table” (Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:1409).

When Justice James Wilson addressed the ratification convention in Pennsylvania, he focused on the credibility of commerce with the global community when he argued:

[t]he judicial power extends to all cases arising under treaties made or which shall be made by the United States … it is highly proper that this regulation should be made; for the truth is, I am sorry to say it, that in order to prevent payment of British Debts, and from other causes, our treaties have been violated and violated too by the express laws of several states in the union. … the Minister of the United States [John Adams] made a demand of Lord Carmarthen of a surrender of the western posts, he told the minister, with truth and justice, “The treaty under which you claim these possessions has not performed on your part. Until that is done, those possessions will not be delivered up.” This clause sir [the Article establishing the Judiciary] will show the world that we make good faith of treaties a constitutional part of the character of the United States … for the judges of the United States will be enabled to carry them into effect …

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:517).Moreover, Justice Wilson, when discussing the clause granting original jurisdiction to the Court over disputes involving ambassadors, made the following observations:

It was thought proper to give citizens of foreign states full opportunity of obtaining justice in the general courts, and … therefore in order to restore credit with those foreign states, that … is necessary. I believe the alteration that will take place in their [foreigners'] minds, when they learn the operation of this clause, will be a great and important advantage to our country, nor is it anything but justice. … Further, it is necessary to preserve peace with foreign nations. Let us suppose the case, that a wicked law is made in some one of the states, enabling a debtor to pay his creditor with the fourth, fifth, or sixth part of the real value of the debt, and this creditor, a foreigner, complains to his prince or sovereign, of the injustice that has been done him. What can that prince or sovereign do? Bound by the inclination as well as the duty to redress the wrong his subject sustains from the hand of the perfidy, he cannot apply to the particular guilty state because he knows that … it is declared that no state shall enter into treaties. He must therefore apply to the United States. The United States must be accountable. My subject has received a flagrant injury; do me justice, or I will do myself justice

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:520).Oliver Ellsworth, later chief justice, during the Connecticut debates reported his concerns regarding the absence of an avenue of redress for foreign powers. He argued:

Another ill consequence of this want of energy [or power in the Confederation system] is that treaties are not performed. The Treaty of Peace with Great Britain was a very favorable one for us. But it did not happen perfectly to please some of the states, and they would not comply with it. The consequence is Britain charges us with the breach and refuses to deliver up the forts [western posts] …

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:544).The delegates to the Massachusetts ratification convention were also concerned about trade and commerce with foreign nations and the Confederation's inability to establish credible commitments with those actual and potential trading partners. Rufus King made this observation:

But it is not only our coastal trade, our whole commerce is going to ruin. Congress has not had the power to make even a trade law, which shall confine the importation of foreign goods to the ships of the producing or consuming country. If we had such a law, we should not look to England for the goods of other nations; nor would British vessels be the carriers of American produce from our sister states. … Our sister states are willing we should receive these benefits and that they should be secured by national laws; but until that is done, their private merchants will, no doubt, for the sake of long credit, … prefer the ships of foreigners …

(Reference JensenJensen et al. 1976:1288).The constructive intent that underpinned the creation of the judiciary seems clear from the content of the arguments at the state ratification debates. This institutional role for the federal courts was not only intended but also was implemented, first by the Judiciary Act of 1789 and then by the cases and controversies considered by the system before Marshall's tenure as chief justice began in 1801.Footnote 12

The Judiciary Act of 1789

The framework for the Court established by the Constitution was filled out by the Judiciary Act of 1789. John Jay, the first chief justice, said this in describing both the intent and structure of the Court to a grand jury in April 1790:

[w]e were responsible to others for the observance of the Law of Nations; and as our national Concerns were to be regulated by national Laws national Tribunals became necessary for the Interpretation & Execution of them both … The Manner establishing it, with Powers neither too extensive, nor too limited; rendering it properly independent, and yet properly amenable, involved Questions of no little Intricacy …

(Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 2, 27–8; emphasis in original).The Judiciary Act of 1789 contained a variety of jurisdictional provisions as well as the mechanism for the establishment of inferior courts. Although virtually every aspect of the act was controversial, even its most ardent opponents agreed that the federal courts should have jurisdiction over admiralty cases (Casper, in Reference MarcusMarcus 1992:293). There can be little doubt that the act was an embodiment of the ongoing resolution of political disputes between the strategic actors who sought to influence the institutions they designed. It seems equally true that the act did not discard but rather refined the early intent as expressed in the Constitution. For example, the Alien Torts Claim Act (part of the Judiciary Act) vests jurisdiction in the federal courts for claims of tort by aliens.Footnote 13 The most important sections of the Judiciary Act were sections 22 and 25. Section 22 established the lower courts and set forth the basis for appeal from district court decisions. Section 25 specifically provided for final federal jurisdiction over cases that challenged treaties, federal statutes, or other exercises of federal power. By depriving the individual American states of the ultimate power to resolve disputes between aliens and citizens, the act maintained the federal prerogative for the adjudication of issues that could lead to aggression on the part of another nation. The federal courts could ensure that hostile nations could not invade the states or attack the trade routes and ships under the auspices of protecting the rights of their own citizens without breaching the prohibition of unjustified belligerence that underpinned the law of nations.

U.S. Cases and Controversies

A circumstance which crowns the defects of the confederation, remains yet to be mentioned—the want of a judiciary power. Laws are a dead letter without courts to expound and define their true meaning and operation. The treaties of the United States to have any force at all, must be considered as part of the law of the land … The treaties of the United States, … are liable to the infractions of thirteen different Legislatures, and as many different courts of final jurisdiction … The faith, the reputation, the peace of the whole union, are thus continually at the mercy of prejudices, the passions, and the interests of every member of which it is composed. Is it possible that foreign nations can either respect or confide in such a government … ?

(The Federalist, No. 22, December 14, 1787)Cases are used here to illustrate both the procedural limits of the Court and the substantive areas of greatest concern. Although a few cases were never properly reported, most of the early cases and controversies before the Court are well documented (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:147).Footnote 14 And even many of the cases that were not fully reported are sufficiently documented to inform this discussion. A discussion of several specific cases is followed by a comprehensive analysis of the jurisdictional basis of all of the cases decided before 1801, when Marshall became chief justice.

The first case entered on the docket of the Supreme Court involved a dispute between two Dutch bankers and the state of Maryland. The case of Nicholas and Jacob Vanstaphorst v. State of Maryland (1791) was initiated when Maryland failed to abide by the terms of a loan it had negotiated with the van Staphorsts as the war was concluding (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 191).Footnote 15 Although the case has been construed by scholars as primarily concerned with the “suability of states” (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 5, 7), a consideration of the facts and the proceedings show that the case entails a great deal more than the question of whether states could be sued. As the British advanced in early 1781, Maryland needed funds to pay for the necessary goods of war. Matthew Ridley was appointed by Maryland to procure a loan and, with those funds, supplies so that the state could defend itself (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 5, 7). Specifically, Ridley was to secure the loans from France, Spain, or Holland with a cap on the annual interest of no more than one thousand hogsheads of tobacco or four thousand barrels of flour (Reference SteinerSteiner 1927: 365; Votes and Proceedings 1781:62). The thousand hogsheads equaled 1 million pounds of tobacco (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 5, 7).Footnote 16 Ridley first tried to obtain the loan from the French. He was unsuccessful ultimately because the ministers of Louis XVI were unwilling to lend money to one of the individual constituent states rather than the collective of the new nation (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 5, 7–9).Footnote 17 In other words, a loan to a state was too risky of an investment for the French.

Ridley next turned to the Amsterdam investment banking firm of Fizeaux, Grand & Co. but was unable to elicit an offer to lend. He then opened negotiations with Jacob van Staphorst and reached an agreement with the brothers by the end of July 1782 (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 5, 8). Ridley and the van Staphorsts executed a bond that memorialized Maryland's obligation to repay the loan and a contract that set forth the terms of interest.Footnote 18 The van Staphorsts were expanding their level of investment in the new country and had just completed a comparable, if larger, arrangement with John Adams on behalf of the Continental Congress.Footnote 19 Beyond scale, another significant difference between the national- and state-level agreements was that Maryland was to repay the interest with tobacco instead of money. The agreement called for the state of Maryland to deliver one thousand hogsheads of tobacco at the price of 14 livres per hundred pounds every year for 10 years. The interest due would be paid out of the delivery.Footnote 20

In essence, Ridley had negotiated the interest at the maximum rate he was authorized by the state to procure. Moreover, the inelegant structure of the contract meant that the van Staphorsts and Maryland interpreted the interest obligation in substantially different ways.Footnote 21 From the perspective of the van Staphorsts, they were entitled to purchase the agreed-upon amount of tobacco at the agreed-upon price for the agreed-upon time frame. From the perspective of Maryland, the state was bound to deliver only so much tobacco as would satisfy the actual interest debt.Footnote 22

Although the bankers negotiated a settlement with representatives of the state, the Maryland legislature objected to the agreement (Reference BogelBogel 1996). The van Staphorsts tried to settle the debt with Maryland for more than seven years before ultimately resorting to the new federal court system. The attorney for the van Staphorsts sought an order—“commission,” in the parlance of the time—for discoveryFootnote 23 for the purposes of taking the depositions of certain witnesses who were citizens of Holland.Footnote 24 While Maryland did not object to discovery, the Court refused to allow the depositions until the “commissioners” were named (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 192). Once the commissioners—those who would represent the van Staphorsts and Maryland at the depositions—had been identified, the Court ordered that the depositions proceed and that at least one commissioner representing each party attend the depositions. Important to note, the representatives of the parties were ordered to certify the depositions and were put on notice that the depositions “shall be read and received as evidence on the trial” (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 196). The commissioners were all Dutch attorneys (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 196). As the case moved along procedurally, Anti-Federalists in the Maryland legislature began to complain about the implication of the Court establishing clear jurisdiction over the states (Reference BogelBogel 1996). Indeed, this concern led the state legislature to authorize a settlement of the suit, and the van Staphorsts dismissed the case after payment (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 201).

The Dutch banking community heavily invested across the new country (Reference EvansEvans 1924). The van Staphorst case sent a significant signal to the balance of the investment community as well as to the van Staphorsts themselves. First, the Court took jurisdiction. This step alone signaled that the Court was willing at a minimum to consider enforcing the contracts for debt between the states and foreign interests. Second, the Court conveyed its impartiality by declining to order discovery until the commissioners were identified. The impartiality of the process was underscored by the Court's acceptance, for the purpose of discovery, of Dutch attorneys as officers of the Court. As the Maryland legislature made clear and in light of the protracted attempt by the van Staphorsts to resolve the dispute amicably, there can be no question that the settlement came about as a result of the Court's consideration of the dispute.

Thus the Court established itself at the outset as a venue wherein the foreign investor could seek restitution if aggrieved—even when wronged by a state. The simple existence of an administrative avenue through which to seek redress extended the time horizon of the creditor. That is, by establishing that creditors could seek redress without the need to turn to self-help, the Court made extending credit to the states a less risky venture for investors. While many of the cases before the early Court were decided on narrow procedural grounds, that foreign investors had a venue in which to pursue claims at all was remarkable. An administrative avenue for the pursuit of a remedy allowed commerce to occur in a field of credibility. Should the economic interests in the United States breach their agreements, a venue comparable, if not identical, to a King's Court was available.

While the van Staphorsts and Maryland were choosing their commissioners for discovery and ultimately negotiating a settlement, the Court heard or considered the following cases: U.S. v. Eleanor McDonald (1792), West v. Barnes (1791), Oswald, Holt v. New York (1792), and In re Hayburn (1792; Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 199–201).Footnote 25 Shortly after the van Staphorst settlement, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) was filed (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 205).

In U.S. v. Eleanor McDonald (1792), the defendant was accused of stealing 11 gold doubloons from a vessel in the Delaware River captained by Henry Williams (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 194). McDonald was charged under portions of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that made larceny on the high seas an act against the United States as well as against the victim of the larceny.Footnote 26 The Court's involvement was limited to setting a special session of the circuit court in Philadelphia so as to avoid any substantial delay of Captain Williams's scheduled departure. Simply put, the Court ordered an expedited trial expressly to avoid the unnecessary interference with trade and delay in shipping out that the normal process would have entailed.

In West v. Barnes (1791), a simple commercial dispute, the Court unanimously declined to accept the efforts by some of the defendants to remove to the federal courts the case from a state court in Rhode Island. At this first opportunity, the Court signaled that it was not an institution designed or willing to resolve all types of disputes (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 195). Rather, it had a limited function, and it would not engage in general dispute resolution. In Oswald, Holt v. New York (1792), the estate of a Pennsylvania printer, John Holt, sued the state of New York for money owed for printing services (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 198, 200). Although the Court ordered New York to respond, New York had declined to recognize the Court's jurisdiction based upon a sovereign immunity claim (Reference BogelBogel 1996). A series of procedural questions delayed any adjudication of Oswald by the Court until after it decided that states could be sued by individuals in Chisholm v. Georgia (1793).

Hayburn (1792) addressed an attempt by Congress to expand the role of the Court by imposing extrajudicial duties on the justices (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:147–52). Perhaps surprisingly to those who believe that Marbury v. Madison (1803) was the first instance of the Court invalidating an act of Congress, the Court struck down as unconstitutional the congressional mandate that the justices become pension commissioners. The Court held that “neither the Legislature nor the Executive branches can constitutionally assign to the judicial [branch] any duties, but such are properly judicial, and to be performed in a judicial manner” (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:147–52). The case is noteworthy here because it indicates the justices believed their roles were limited in scope and could not be expanded by the other branches. In 1798, the Court again addressed the question of judicial review in Calder v. Bull (1798), where it held that conflicts between state constitutions and state laws do not fall within the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary.Footnote 27

Chisholm v. Georgia (1793) addressed the jurisdiction of the Court.Footnote 28 Two citizens of South Carolina sued Georgia for debt that the state legislature had incurred during the Revolution (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:158–65). Georgia refused to recognize jurisdiction based on its claim of sovereign immunity.Footnote 29 The Court ruled that Georgia could be sued under Chief Justice Jay's rationale that the language of the Constitution conveyed jurisdiction to the Court. Justice Wilson concurred and explained his position thus:

This is a case of uncommon magnitude. One of the parties to it is a State; certainly respectable, claiming to be sovereign. The question to be determined, is, whether this State, so respectable, and whose claim soars so high, is amenable to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United States? This question, important in itself, will depend on others, more important still; and may, perhaps be ultimately resolved into one, no less radical than this—“do the people of the United States form a nation?”

(Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:162).At roughly the same time as Chisholm, Grayson et al v. Virginia (1798, later re-captioned Levi Hollingsworth et al v. Virginia) was filed (Reference GoebelGoebel 1971:724).Footnote 30Grayson was brought on behalf of the shareholders of the Indiana Company for their losses arising out of Virginia's nullification of the company's title to a large tract of land that Virginia claimed was inside its westernmost boundary. Although the Court issued a subpoena ordering Virginia Governor Henry Lee and Virginia Attorney General Harry Innes to appear in the Supreme Court, neither obeyed (Reference GoebelGoebel 1971:725).

Controversy over whether the states were subject to the Court's jurisdiction erupted over Chisholm and Grayson/Levi Hollingsworth. Former Virginia Governor and then United States Attorney General Edmund Randolph was the plaintiffs' counsel in Grayson/Levi Hollingsworth. He argued that states were indeed subject to the jurisdiction of the Court in part because adjudication through a court was preferable to the risk of the states going to war with each other (Reference GoebelGoebel 1971:728).Footnote 31 Randolph had made this same “harmony between the states” argument at the Virginia ratifying convention (Reference ElliotElliot 1836: Vol. 3, 570–1).

Shortly after Chisholm and Grayson/Levi Hollingsworth, the Court heard Brailsford v. Georgia (1794). Brailsford concerned the rights of, among others, a British subject residing in Great Britain to repayment of debt. While the facts are tangled by the procedural maneuvers of the parties, an explanation of the rationale is instructive here: “[w]e are also of the opinion that the debts due to Brailsford, a British subject residing in Great Britain, were by the statute of Georgia subjected, not to confiscation but only to sequestration; and therefore, that his right to recover them, revived at the peace, both by the law of nations and the treaty of peace” (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:178). Brailsford committed the Court to upholding treaties, enforcing contracts even with foreigners, and giving the dignity of enforcement to the law of nations.

Next, Glass v. The Sloop Betsey (1794) involved a commercial boat, The Sloop Betsey, which was owned by Swedes and Americans. It was captured on the high seas and condemned as prize by the French consul in Maryland. The Court couched the controversy as “whether any foreign nation had a right without the positive stipulations of a treaty, to establish in this country an admiralty jurisdiction for taking cognizance of prizes captured on the high seas by its subjects or citizens from its enemies?” (Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:172). The Court ruled:

[n]o foreign power can of right institute or erect any court of judicature of any kind, within the jurisdiction of the United States, but such only as may be warranted by and be in pursuance of treaties, it is therefore decreed and adjudged that the admiralty jurisdiction, which has been exercised in the United States by the consuls of France, not being so warranted, is not of right

(Reference LankevichLankevich 1986:173).Reference WarrenWarren claims, “No decision of the Court ever did more to vindicate our international rights, to establish respect among nations for the sovereignty of this country, and keep the United States out of international complications” ([1923] 1947:117).

All these cases show that the early Court primarily concerned itself with cases involving disputes with foreign nationals or countries, admiralty law, disputes involving states, and issues regarding treaties. Other cases that support this argument include but are not limited to Penhollow v. Doanes's Administrator, 3 Dallas 54 (1795) (upholding the decree of a prize court established under the Articles of Confederation); Talbot v. Jansen, 3 Dallas 133 (1795) (capture of a Dutch ship by two Americans who unsuccessfully sought to avoid U.S. neutrality by renouncing citizenship); Ware v. Hylton, 3 Dallas 282 (1796) (The Treaty of Paris overrides state law); United States v. La Vengeance, 3 Dallas 297 (1796) (admiralty law jurisdiction extends to inland waters and the Great Lakes); and Moodie v. The Ship Phoebe Anne, 3 Dallas 319 (1796) (French privateer could make repairs in U.S. port to British ship captured as prize).

Indeed, most cases decided by the Court prior to Marshall's tenure as chief justice in some way enhanced trade either by protecting the integrity of contracts (especially with foreigners or foreign powers), or by reducing the potential for conflict among the states or between the states and foreign powers. Those few cases, such as Hayburn, that did not fall into one of those two categories jealously guarded against the expansion of the role or duties of the Court.

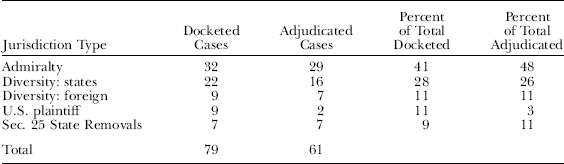

Ninety-one cases were docketed or adjudicated prior to Marshall's ascent to the position of chief justice in 1801.Footnote 32 Only 12 of those cases were original jurisdiction cases, and each named a state as a party. All others were appellate jurisdiction cases as set forth in the Judiciary Act of 1789.Footnote 33Table 1 provides a jurisdictional analysis of every appellate case docketed or adjudicated by the Supreme Court prior to Marshall's ascension as chief justice in 1801 (see Table 1).Footnote 34

Table 1. Appellate Cases Docketed and Adjudicated Prior to 1801

“Jurisdiction” is the legal basis for the authority of the Court to hear any particular case. “Docketed Cases” are those cases placed on the Court's schedule—the docket. The “Adjudicated Cases” are those that culminated in an opinion by the Court that dispensed with the case in some fashion. Some cases were docketed but not adjudicated because the parties reached a settlement or the plaintiffs chose to abandon their claim for some reason.Footnote 35“Admiralty” jurisdiction arose because of some dispute involving the law of the seas. “Diversity: states” jurisdiction arose because of disputes between citizens of different states. ‘Diversity: foreign” jurisdiction arose because of disputes between foreign nationals or countries and U.S. citizens. Every admiralty case involved at least one other foreign country or citizen, and the “Diversity: foreign” cases involved foreign countries or citizens with some non-admiralty grievance. “U.S. Plaintiff” cases, where the United States was the plaintiff, are suits on customs bonds, an assumpsit for Continental Loan Certificates, and one case for a debt on a statute.Footnote 36“Sec. 25 State Removals” are those cases removed to the Court under the authority of section 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, which conveyed jurisdiction to the Court when the validity of a treaty, federal statute, or other federal authority was questioned.Footnote 37

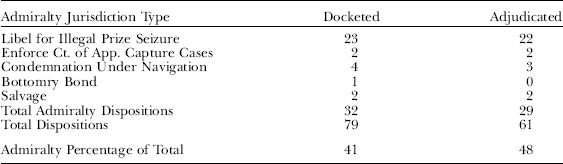

Of the 32 admiralty cases docketed, 23 involved attempts to receive restitution for a ship illegally seized as prize. Of the 29 admiralty cases adjudicated, 22 resolved those prize cases. British libellantsFootnote 38 accounted for 15 of the 29 adjudicated cases. Spanish libellants accounted for four of them. Two cases involved Dutch libellants. One case was prosecuted on behalf of citizens of both Sweden and the United States, and one case was on behalf of a libellant from the United States. The remaining seven adjudicated cases comprised two cases seeking to enforce a judgment of the Court of Appeals in cases of capture, three cases for condemnation under navigation laws, and, two cases of salvage from the oceans. Thus the admiralty cases can be substantively categorized in Table 2.

Table 2. Jurisdiction Type for Admiralty Cases

This empirical explication of the bases of jurisdiction and the analysis of the variety of admiralty cases suggest that trade was the paramount concern of the Court. Moreover, these data also suggest that the Court was the recognized venue for resolution of these matters. English, Spanish, or Dutch citizens would be unlikely to pursue claims in the Court if there was no chance of prevailing.

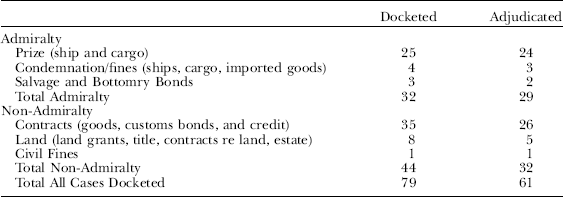

In other words, since foreign litigants sought relief in the Court, they must have had a reasonable expectation that relief could be granted. However, the theory set forth here is supported by more than simply the evidence of the categorical jurisdiction. As shown in Table 3, an analysis of the economic basis of the cases docketed and adjudicated by the Court further reveals the prominence of trade and contracts in the business of the Court (see Table 3).

Table 3. Economic Basis of Litigation

Twenty-two of the cases included a reliance by the defendant on a treaty as a defense to either the substantive merits or the jurisdictional grounds of the action, and in nine cases the plaintiff relied upon a treaty for some element of the case. The treaties included the Treaty of Paris, the French Treaty, the Jay Treaty, and the Dutch Treaty of Comity and Commerce.Footnote 39 The Court affirmed 41 cases on the merits, including one case affirmed in part and reversed in part, and it reversed 12 cases on the merits and eight cases on jurisdictional grounds.

When considered as a group, the cases enhanced trade either by protecting the integrity of contracts—especially with foreigners or foreign powers—or by reducing the potential for conflict among the states or between the states and foreign powers. Whether the Court was interpreting a treaty or simply assessing the claims of damages arising out of the seizure of ships and goods, the aggregate posture of the institutional law of the land was that contracts could be trusted and all aggrieved were allowed to make their claims. Given the ability of foreign interests to prosecute claims and prevail in that prosecution, the Court provided an administrative remedy to settle grievances that was significantly less costly than belligerence. The existence of the Court (or some avenue of redress) was a necessary although not sufficient condition to ensure credible commitments in trade. As would be expected, most contracts do not end in litigation. However, the risk management aspect of trade and commerce dictates that—in the event the parties are not in agreement—there must be some mechanism for resolving any conflict. The Court provided that mechanism.

International Relations and a Reconsideration of the Career of John Jay: Correspondence, Speeches, and Publications

The argument made here is supported by more than the empirical evidence of the case law or the institutional intent derived from the debates and documents that created the system. In addition, a consideration of various letters, speeches, and publications of the first Supreme Court chief justice, John Jay, as well other notables of the time, strengthens this assessment. For example, in a series of letters from George Washington to Jay in 1779, Washington expressed his worry about the damage to the trade and credit of the new country caused by the ongoing war with Britain (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:207–11). In April 1779, Washington wrote to Jay:

Will Congress suffer the Bermudian vessels, which are said to have arrived … to exchange their salt for flour …? Indulging them with a supply of provisions at this time will be injurious to us in two respects: it will deprive us of what we really need in stead for ourselves, and will contribute to the support of that swarm of privateers which resort to Bermuda, from whence they infest our coast, and in a manner annihilate our trade …

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890: 206–7).Jay responded to Washington and expressed his concern that the committee system in the Continental Congress would perpetually inhibit the growth of maritime trade:

While the maritime affairs of the continent continue under the direction of a committee, they will be exposed to all the consequences of want of system, attention and knowledge. The marine committee consists of a delegate from each state; it fluctuates; … few members have time or inclination to attend to them … The commercial committee was equally useless. A proposition was made to appoint a commercial agent for the states under certain regulations. Opposition was made. The ostensible objections were various. The true reason was its interfering with a certain commercial agent in Europe and his connections …. There is as much intrigue in this state-house as in the Vatican, but as little secrecy as in a boarding-school …

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:210).Indeed, to find proof of the early concern with trade and international acceptance of American contracts, there is no need to go beyond the Circular-Letter From Congress To Their Constituents, authored by Jay at the request of Congress on September 8, 1779 (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:218–36). As president of the Continental Congress, Jay wrote the letter to accompany a series of resolutions passed to address the growing economic crisis. When considering the possibility of American defaults on foreign contracts and loans, Jay declared:

A bankrupt, faithless republic would be a novelty in the political world, and appear among reputable nations like a common prostitute among chaste and respectable matrons. The pride of America revolts from the idea … . We are convinced that the efforts and arts of our enemies will not be wanting to draw us into this contemptible situation. Impelled by malice and the suggestions of chagrin and disappointment at not being able to bend our necks to their yoke, they will endeavor to force or seduce us to commit this unpardonable sin, in order to subject us to the punishment due to it, and that we may henceforth be a reproach and a byword among the nations. Apprized of these consequences, knowing the value of national character, and impressed with a due sense of the immutable laws of justice and honour, it is impossible that America should think without horror of such an execrable deed … . Let it never be said, that America had no sooner become independent than she became insolvent, or that her infant glories and growing fame were obscured and tarnished by broken contracts and violated faith in the very hour when all the nations of the earth were admiring and almost adoring the splendour of her rising

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:232–3, 235–6).Shortly after the Circular-Letter was published, Jay left Congress to represent the American states at the court of Madrid (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:247). His instructions from Congress expressly directed him to “obtain a treaty of alliance and of amity and commerce …” (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:249). The concern for commerce was coupled with a concern for credibility in commerce as well. Jay wrote to Benjamin Franklin, “American credit suffers exceedingly in this place [Spain] from reports that our loan office bills payable in France have not been duly honored but have been delayed payment under various pretexts …” (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:254–5). Indeed, the purpose of Jay's mission to Spain was to secure trade relations with Spain and solidify trade with France.Footnote 40 While these letters do not alone suggest that the Court was to be driven by trade, they do show the overarching concern for the establishment of credible commitments in commerce. When the Constitution was drafted, that concern was ameliorated through the establishment of the Court.

Once the Constitution was embraced by the Continental Congress, many prominent citizens began to jockey for the office of chief justice—it was hardly considered the undesirable post described by modern scholars. For example, the Philadelphia newspaper the Independent Chronicle opined in its July 12, 1788, edition that “the great American Fabius (George Washington) … will undoubtedly be President–General. … Mr. Adams will undoubtedly be Chief Justice of the Federal Judiciary” (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 601). In part, the basis for assuming that John Adams was to be named chief justice was his post from 1778 to 1788 as American representative in France, Holland, and England as well as his role in negotiating the Treaty of Paris in 1783 (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 602).Footnote 41

The Massachusetts Gazette confirmed the rumors of the appointment of Adams but suggested that Massachusetts natives William Cushing and Francis Dana should also be considered (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 602–3). Cushing was chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, and Dana had been a diplomat to France and Russia. Friends of Justice Wilson, one of the leaders of the fight for ratification of the Constitution in Pennsylvania, tried to persuade Washington to appoint Justice Wilson chief justice.Footnote 42 Indeed, Justice Wilson himself formally applied to Washington for the job on April 21, 1789 (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 606). Many other prominent citizens were mentioned for or sought the job of chief justice, including Aedanus Burke of South Carolina, Edmund Pendelton of Virginia, and William S. Johnson of Connecticut (Reference MarcusMarcus 1988: Vol. 1, 612). Ultimately, the list of potential candidates for chief justice was whittled by Washington to two men: Justice Wilson and Jay. Arthur Lee, physician and one-time diplomat to England and France, wrote, “Wilson is an avowed candidate for the Chief Justice ship-Jay is the whispered one …” (Letter, Arthur Lee to Francis Lightfoot Lee, 9 May 1789 [Reference Marcus and PerryMarcus & Perry 1985: Vol. 1, part 2, 617]).

Although the evidence of prominent citizens’ desire to be appointed to the Court may not have risen much beyond political gossip from the press, perhaps the most telling evidence of the desirability of the post is that a citizen as prominent as Jay accepted the position. Jay received his commission of office for chief justice from Washington on October 5, 1789 (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890: 378).Footnote 43 Chief Justice Jay's first public elaboration of his view of the role of the Court was in his Charge To Grand Juries By Chief Justice Jay, which was read to grand juries in New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire during April and May 1790 (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:387–95). He said in part:

The most perfect constitutions, the best governments, and the wisest laws are vain, unless well administered and well obeyed … You will recollect that the laws of nations make part of the law of this and every civilized nation. They consist of those rules for regulating the conduct of nations toward each other which, resulting from right reason, receive their obligations from that principle and from general assent and practice. To this head also belong those rules or laws which by agreement become established between particular nations, and of this kind are treaties, conventions, and the like compacts; as in private life a fair and legal contract … cannot be annulled nor altered by either without the consent of the other. … We are now a nation and it equally becomes us to perform our duties as to assert our rights

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:393–5).Before the justices of the newly formed Court embarked on their first tour of duty on the circuits, Washington wished them well and asserted:

I have always been persuaded that the stability and success of the national government, and consequently the happiness of the people of the United States, would depend in a considerable degree on the interpretation and execution of its laws. In my opinion, therefore, it is important that the Judicial system should not only be independent in its operations, but as perfect as possible in its formation

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:396).Footnote 44As is clear from their words, before the Constitution was adopted and as the judiciary was staffed, Washington, Jay, and many of the other Founders maintained a concern with trade and foreign relations. Even after Jay assumed the role of chief justice, he continued to be an integral part of the ongoing dialogue regarding trade, commerce, security, and foreign relations (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890: 404–5).Footnote 45 In November 1790, when still serving as chief justice, Jay wrote to Alexander Hamilton regarding a variety of trade policies to be implemented by Congress:

I have heard it suggested that a revenue officer should be stationed on the communication with Canada. The facility of introducing valuable goods by that route is obvious. The national government gains ground in these countries, and I hope care will be taken to cherish the national spirit which is prevailing in them. The deviation from contract touching interest does not please universally …

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:410–11).Perhaps nothing so exemplifies Jay's concern with trade and foreign relations as his draft of the Proclamation of Neutrality. The proclamation issued by Reference WashingtonWashington on April 22, 1793, while consistent in tone and spirit, was less specific and more brief than Jay's (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:474–7). The Jay draft asserted:

whereas a new form of government has taken place and actually exists in France, that event is to be regarded as the act of the nation until that presumption shall be destroyed by fact … although the misfortunes, to whatever cause they may be imputed, which the late King of France and others have suffered in the course of that revolution, or which that nation may yet experience, are to be regretted by the friends of humanity, and particularly by the people of America to whom both that king and that nation have done essential services, yet it is no less the duty than the interest of the United States strictly to observe that conduct towards all nations which the law of nations prescribes. And whereas war actually exists between France on the one side and Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, and the United Netherlands on the other … it is our duty by a conduct strictly neutral and inoffensive to cultivate and preserve peace …

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:474–7).Both the Jay draft and the proclamation ultimately issued by Washington advised the citizenry to avoid provoking, through private acts, any of the belligerent powers (Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:474–7). Jay's 1793 grand jury charge in Richmond, Virginia, included the following:

The Constitution, the statutes of Congress, the laws of nations, and treaties constitutionally made compose the law of the United States.

You will perceive that the object is twofold: To regulate the conduct of the citizens relative to our own nation and people, and relative to foreign nations and their subjects.

To the first class belong those statutes which respect trades, navigation and finance … Among the most important are those which respect the revenue …. Justice and policy unite in declaring that debts fairly contracted should be honestly paid. On this basis only can public credit be erected and supported. … The success of loans will always depend on our credit; and our credit will always be in proportion to our resources, to our integrity, and to our punctuality

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890:486–7).As Reference WashingtonWashington's Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson wrote to the Court in 1793:

The war which has taken place among the powers of Europe produces frequent transactions within our ports and limits, on which questions arise of considerable difficulty, and of greater importance to the peace of the United States. These questions depend for their solution on the construction of treaties, on the laws of nature and nations, and on the laws of the land …. The President … would be much relieved if he found himself free to refer questions of this description to … the Supreme Court of the United States whose knowledge of the subject would secure us against errors dangerous to the peace of the United States, and their authority insure the respect of all parties

(Reference JohnstonJohnston 1890: 486–7).Although the Court later declined to embrace advisory opinions, Jefferson's conception of the role of the Court in trade and finance is clear. Taken as a whole, the cases and controversies and the views of the Founders indicate that the pre-Marshall Court was not a mere theoretically driven but unimportant institution. Rather, because trade was key to survival of the economy, upholding trade agreements and the concomitant commercial contracts was critical to the survival of the new country. Moreover, hostile nations that might have used trade as an excuse for belligerence were held at bay through the provision of the administrative avenue for grievance provided by the Court. Not only was a perfect remedy available, but the failure to avail oneself of the provided remedy was a breach of the law of nations.

Implications and Conclusion

The early Court has been grossly underestimated in both form and function. The analysis presented here does not rival conventional wisdom so much as complement it. The conventional description is that the Court has gone through three distinct deliberative eras (Reference SchwartzSchwartz 1993:378–80; Reference Kernell and JacobsonKernell & Jacobson 2006:349–54). First, the Court addressed questions of nation-to-state relations. Second, the Court addressed the limitations of government regulation of the economy. Third, the Court engaged issues of civil rights and liberties.Footnote 46 The research presented here shows that the true first era and the antecedent to these well-recognized eras of the Court was the sovereign-to-sovereign era.

The disregard with which most scholars consider the early Court is no doubt largely an outcome of both the length of Marshall's tenure and the impact of his decisions. Moreover, the Court was so successful in the early management of international relations that the issue of credibility—or at least the enforceability—of U.S. commitments was settled by the time Marshall took the gavel. As the Court progressed through each phase of development, issues of greater domestic controversy moved to the forefront of consideration. Because of the successful early era of the Court, even today the international community, the political community, the legal community, scholars, and the public all expect contracts to be enforced.

Thus systemic credibility is the legacy of the first Court. Prior to Marshall, the Court had the specific institutional role of providing an administrative remedy to aggrieved nations to deprive those hostile nations of any trade-based excuse for belligerence. Original jurisdiction was designed primarily to remedy trade disputes. The independent judiciary made trade commitments more credible and self-help by the aggrieved less likely. By providing this administrative remedy and reducing the uncertainty associated with trading with revolutionaries, the Framers claimed a seat for the nascent country at the table of nations. Establishing the credibility of the new government among the world's great nations as well as our trading partners was a necessary prerequisite to consolidation of the economy and, thus, consolidation of the government itself. An independent judiciary was the avenue most clearly available to the Framers for the provision of this credibility. This analysis is not only consistent with the categorical development of the extant literature but also informs larger questions of nation-building or democratic consolidation. The lesson from the early era of the Supreme Court is that credibility of commitments with foreign interests is integral to stability and development.

Finally, there may also be broader implications for ongoing debates about the original intent of the Framers and interpretation of the text of the Constitution. The argument and evidence presented here indicates that the immediate judicial concern of the Framers was driven by trade issues. This research presents Marshall as—effectively—the first “activist” justice. Marshall took the Court in a very different institutional direction than expected by the Framers. Still those very architects of government who were focused on the Court's role in trade did not restrict Marshall in any meaningful sense. Accordingly, we must reach one of two conclusions. The Framers in power at the time of Marshall's stewardship of the Court either agreed with him on the fundamental direction he took the Court, or they embraced a Court that changed in response to the times. The consolidation of the economy and trade relationships through the credible commitments provided by the Court, combined with the often adversarial relationship between the Jefferson and Madison administrations and Marshall, suggests that the latter conclusion is the more appropriate one.