Introduction

Many Canadian Muslim couples are hesitant to resort to civil legal processes and attempt to resolve their disputes within the religious community.Footnote 1 Islamic law’s exclusion of non-Muslim judges from holding judicial authority in certain family law matters limits the feasibility of aligning religious commands with family court orders.Footnote 2 Thus, court orders, even if they accord with religious practices, may not be morally authoritative if the judge is not Muslim.

For Muslim minorities residing in non-Muslim countries, classical Muslim jurists theorized alternative forms of judicial authority to accommodate community-led adjudication in the absence of a functioning Islamic system.Footnote 3 Perceiving religious leaders (imams and scholars) as mediators and arbitrators,Footnote 4 many North American Muslim families seek their assistance to resolve marital disputes, creating an unregulated “ad hoc system of individual imams and arbitrators reaching unreported decisions.”Footnote 5 This article identifies the ramifications of such “private ordering” on both the imams and disputants in relation to overlapping secular and religious authorities.

Since most disputes are not resolved by litigation, addressing issues of socio-legal integration for religious minorities through the study of case law is inherently limited. Instead, these issues are better addressed by analyzing the theoretical underpinnings of moral authority and legal bindingness, and the qualitative experiences of how Islamic law is lived by Muslim minorities. The absence of a religious judicial channel for Canadian Muslims or a unified clerical hierarchy limits the guiding sources of Islamic law to the legal opinions (fatāwā, sing. fatwā) of communally reputable institutions or the instructions of individual local imams. By extrapolating contemporary fatāwā issued by institutions and narrating experiences of religious leaders in Canada, this article documents the views of both researchers and practitioners on issues relating to religious marriage dissolution in minority settings.

First, the article analyzes fifteen fatāwā issued by governmental and non-governmental bodies across the globe from 2000 to 2021 opining on whether a secular divorce qualifies as a valid Islamic divorce. These fatāwā are influenced by evolving doctrines of the laws of minority (fiqh al-ʾaqalliyāt), exceptions to pre-requisite conditions of judicial appointment, binding implications of contract law, and facilitating access to justice. Second, the paper narrates qualitative findings of Canadian imams’ personal and organizational experiences in mediating marital disputes. The findings are based on semi-structured interviews with twenty Canadian imams from seven different provinces, conducted throughout 2020–2021 as part of an LLM thesis completed at the University of Windsor Faculty of Law. Interviewees were invited to participate through affiliated institutions, such as provincial and national imams’ councils and mosques, or by direct invitation, in a manner pursuant to the University of Windsor Research Ethics Board.

This research finds that most contemporary fatāwā and interviewees do not hold that secular court-ordered divorces suffice as a form of Islamic marriage dissolution when husbands contest them. Both Canadian imams and fatwā-issuing bodies advocate for the development of extra-judicial entities that apply Islamic law’s Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) procedures in a manner recognized by secular authorities.

I. What the Fatwā Says: Islamic Legal Opinions on Court-Ordered Divorces Issued by Non-Muslim Judges

Two authorities are entitled to interpret and apply Islamic law to new cases: a legal scholar (muftī) and a judge (qāḍī). The difference between them is that a muftī issues a non-binding legal opinion (i.e., fatwā) while a qāḍī issues a legally and morally binding judgment (ḥukm).Footnote 6 Given this binding nature of judgments, Islamic law restricts judicial appointments with stringent eligibility conditions. One of the conditions agreed upon by the majority of Islamic schools of law is that the qāḍī must be a Muslim.Footnote 7 However, almost all legal schools accommodate exceptions to some conditions to enhance communal independence and ensure social stability.Footnote 8 For instance, if the governmental appointment process for qāḍīs is absent, Islamic law entrusts community leaders to either recognize temporary adjudicators or replace them.Footnote 9 Notably, many of these exemptions facilitating access to justice developed in the family law context. Nonetheless, the condition requiring the judge to be Muslim has never been waived by classical Muslim jurists.

Among the multiple Islamic marriage dissolution methods, two do not require the involvement of a judicial decision-maker: ṭalāq and khulʿ. Ṭalāq is “a verbal or written unilateral divorce issued by the husband, explicitly or implicitly signaling his intent to divorce.”Footnote 10 Khulʿ is “a verbal or written bilateral divorce initiated by the wife, denoting divestment. It is a contractual agreement that fiscally compensates the husband in exchange for his release of the marital bond.”Footnote 11 These methods do not inherently align with the secular processes of marriage dissolution:

Only in limited circumstances can a civil divorce or annulment be treated as ṭalāq or khulʿ. A wife who is granted a civil divorce or annulment despite the husband’s contest must independently acquire a religious marital dissolution. To facilitate marital dispute resolutions in Canada, Islamic legal authority is needed to: (1) grant a religious divorce or annulment complementing a civil divorce, and (2) mediate or arbitrate corollary relief using religious laws and principles.Footnote 12

In practice, North American imams differ in their approaches to mediating cases when the husband withholds ṭalāq or his consent to khulʿ. Some imams assume the role of a qāḍī so as to grant an annulment (faskh) or order a divorce (ṭaṭlīq). Both of these methods allow the dissolution of the marriage to proceed according to Islamic law without the consent of an unreasonably recalcitrant husband. The different approaches practiced by imams reflect the jurisprudential arguments propounded by several contemporary fatāwā across the globe.

There are discernible trends in the positions of North American and international fatwā-issuing organizations on the absence of Islamic judicial authority in resolving family matters.Footnote 13 While North American Muslims often consult their local organizations, many immigrants also consult fatwā-issuing councils and governmental bodies from “back home.” Thus, modern fatāwā of both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority contexts inform the legal practices of Muslims in North America. The fatāwā extrapolated in this study date from 2000 to 2021 and are issued by fifteen governmental and non-governmental bodies across the globe.

Fatwā-issuing institutions addressing whether a court-ordered divorce contested by the husband suffices as a religious divorce include governmental bodies in majority-Muslim countries, such as the Egyptian Dar al-Ifta,Footnote 14 the Jordanian Dar al-Ifta,Footnote 15 and the Republic of Iraqi Sunni Endowment Diwan.Footnote 16 Other non-governmental bodies which rely on international contributors include: the Syrian Islamic Council,Footnote 17 the International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA), the Majlisul Ulama of South Africa,Footnote 18 the European Council of Fatwa and Research (ECFR), the Fiqh Council of North America (FCNA), the Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America (AMJA), Darulifta: Institute of Islamic Jurisprudence in the United Kingdom, and Darulifta of Darul Uloom Deoband – India. Collectively, these bodies comprise a large number of scholars with diverse ethnicities and religious and educational backgrounds. With respect to Shia iftā bodies, the Council of Shia Muslim Scholars of North America and the Imam Mahdi Association of Marjaeya (IMAM) have dealt extensively with the issue, given the significance of religious authority and hierarchy within the Shia school. Both bodies comprise a large number of North American Twelver Shia scholars and leaders.

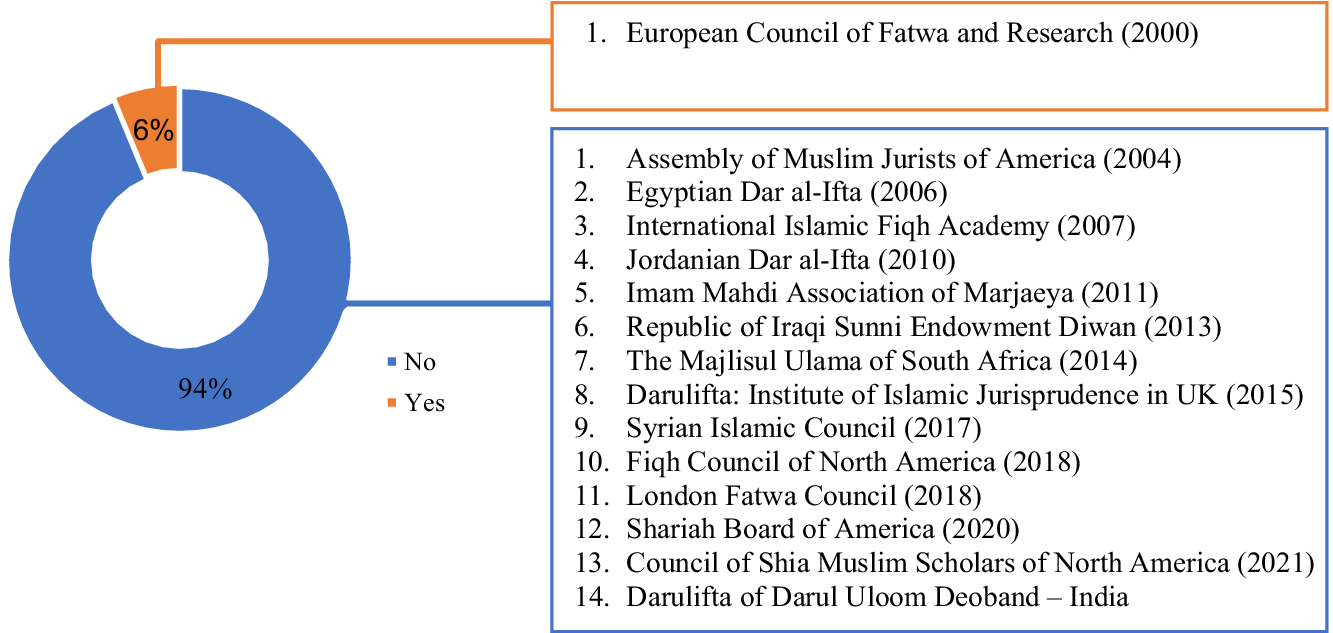

Fourteen of the fifteen statements below strictly commit to Islamic divorce proceedings by holding that a court-ordered divorce obtained by the wife without the verbal or written religious divorce granted by the husband is not religiously binding. Only one fatwā holds otherwise. Figure 1 illustrates the development of the juristic debate across Muslim-majority countries as well as North America and Europe.

Figure 1. One out of fifteen global fatāwā-issuing institutions relieves wives of the obligation to secure a religious divorce when they acquire a court-ordered divorce contested by their husbands.

Since 2000, the ECFR has been the leading authority in legitimizing secular divorces that are contested by husbands.Footnote 19 The ECFR adopted the recommendation of a paper submitted by a Lebanese sharʿī judge, which argues that the husband’s registration of marriage under the civil legal system constitutes his implied consent to civil law authority over the dissolution of marriage.Footnote 20 The paper cautions against the inconsistency of marital statuses between religious and legal processes and advocates for immediacy in securing marital rights. The ECFR further developed this opinion in its twentieth and twenty-fourth annual conferences with guidelines for European “sharʿī judicial bodies” to enforce khulʿ on the husband.Footnote 21 ECFR decisions frequently emphasize the importance of exhausting Islamic arbitration processes before resorting to a civil court to facilitate access to justice for Muslims.

In 2018, the FCNA held that court-ordered divorces issued by non-Muslim judges without the husband’s consent are not religiously binding.Footnote 22 However, according to one participant in the present study, some FCNA members are reviewing the possibility of religiously validating North American divorce decrees. The renewed debate is based on submissions from two of its members in 2020 and 2021 which, as of February 2022, have not resulted in any final statement. FCNA proponents of such validation rely on the same grounds as the European council’s fatwā and emphasize the need to first seek Islamic arbitration, if possible.

In its second conference in 2004,Footnote 23 the AMJA declared the religious illegitimacy of secular divorces contested by the husband and later codified its position in the “Assembly’s Family Code for Muslim Communities in North America” in 2012.Footnote 24 AMJA’s fatwā database documents recurring statements holding this position. For example, in 2007, AMJA refused to approve a Canadian imam’s grant of religious divorce. Instead, AMJA recommended that the husband be convinced to grant a khulʿ through arbitration or mediation.Footnote 25 AMJA had similar recommendations to cases regarding a European couple in 2010Footnote 26 and an American couple in 2011 (the wife was advised to seek ṭalāq from Jordan where she registered the marriage).Footnote 27 The same stance was held by the Shariah Board of America.Footnote 28 Similar statements were issued by institutions from outside North America, such as the London Fatwa CouncilFootnote 29 and the Majlisul Ulama of South Africa.Footnote 30

The International Islamic Fiqh Academy (IIFA) pronounced its decision in its nineteenth session in 2007Footnote 31 after reviewing research proposals by the official muftī of Lebanon, a former Minister of Justice of Mauritania, a judge of the sharʿī council affiliated to the Pakistani Supreme Court, and a professor from Saudi Arabia’s Umm al-Qura University.Footnote 32 The IIFA held that husband-contested secular divorces do not fulfil the requirements of ṭalāq. Instead, IIFA encouraged the use of religious arbitration and stated that Islamic institutions are religiously authorized to represent the Muslim judiciary.Footnote 33

Majlisul Ulama of South Africa criticized a fatwā declaring that “a divorce decreed by a non-Muslim secular court is a valid Talaaq” even if the husband “made the application for dissolution of the marriage,” explaining that:

The divorce decree of a non-Muslim court is directed at the civil contract, not at the Nikah [Islamic marriage contract]. In fact, any court judge will confirm that his verdict has no relationship with the Nikah. It concerns solely the termination of the secular civil contract. Furthermore, the judicial decrees of a non-Muslim judge or a secular Muslim judge have no validity in the Shariah. The non-Muslim court has no wilaayat (jurisdiction) over a Muslim.Footnote 34

The Majlis rejected the minority view’s rationale that the secular judge is implicitly appointed as the husband’s agent (wakīl) to administer ṭalāq on his behalf as a consequence of the husband’s consent to the civil marriage: “This is palpably fallacious. A court judge is not the wakeel (agent) of any of the parties whose case he has to adjudicate. There is no legal system which accepts the ludicrous idea of a court judge being the agent of any of the disputants in front of him.”Footnote 35

In a 2015 fatwā, the Darulifta: Institute of Islamic Jurisprudence in the United Kingdom opined, “if the husband does not sign on any written document or he fails to give his ‘clear’ consent for the court to go ahead with the divorce, but the court [nonetheless] divorces him on behalf of his wife against his will, then this does not constitute a valid Islamic divorce.”Footnote 36

In responding to an intricate scenario questioning the validity of a “civil divorce granted by a French non-Muslim judge,” Darul Uloom Deoband, India, acknowledged that “[w]e are not aware of France’s circumstances” and advised the questioner to contact local scholars who assume quasi-judicial authority as prescribed by the twentieth-century Indian scholar Ashraf Tahānawī,Footnote 37 who endorsed the Mālikī school’s authorization of community members to replace official judges in such circumstances.Footnote 38

The Council of Shia Muslim Scholars of North America issued a statement in 2021 warning Muslim men against abusing their unilateral right to divorce and advising women to “consult a pious religious scholar who is God-fearing and fully familiar with family laws of Islam, and to stay away from anyone who claims to have the authority to divorce on behalf of the al-hakim al-shar’i (religious authority)”.Footnote 39 The council stated that correct Islamic procedures must be sought through religious authorities to legitimately grant ṭalāq. Otherwise, “the divorce will not be [religiously] valid even if the underlying circumstances justify the divorce.”Footnote 40 The council stated,

If it reaches a stage at which divorce by the religious authority is needed, such as when the husband (unreasonably) refuses to divorce his wife or maintain the relationship with her by giving her rights and treating her properly, then no one has the authority to execute the divorce on behalf of Imam al-Mahdi (p) except the qualified jurist or his authorized representative who has been granted such power.Footnote 41

In 2011, consultations with over a hundred experts and key leaders from the Shia Muslim community in North America were conducted and compiled in “The Shia Roadmap.”Footnote 42 The Roadmap was presented to The Council of Shia Muslim Scholars of North America during its eleventh conference, where it received the Council’s endorsement. Based on the Roadmap, the IMAM issued a blueprint document in 2011 including the following recommendations: to “[e]stablish a Shia Muslim Divorce Committee to look into issues of divorce and receive the authority of the Jurist to execute a divorce.”Footnote 43

Summary of Findings: Two Opinions

The minority opinion, represented by one fatwā, considers a divorce ordered by a non-Muslim judge to be religiously binding on Muslims living in non-Muslim majority countries regardless of the husband’s consent. The juristic rationale for this opinion rests on four grounds: 1) the registration of marriage in a non-Muslim jurisdiction denotes an implied consent to its family laws and assigns the husband’s right of divorce to its judges,Footnote 44 2) the legal custom (ʿurf) of the exclusivity of divorce authority to the civil court stands as an implied condition in the marriage contract, 3) the legal and social dilemmas of having inconsistent marital statuses, and 4) the Islamic principles of necessity, public interest, and preventing harm. In addition, the discussion extends to the different roles and authorities judges carry across religious and secular frameworks, rendering some traditional qāḍī qualifications inapplicable today.Footnote 45

The majority opinion, represented by fourteen fatāwā, holds that a divorce granted by a non-Muslim judge without the husband’s consent is of no religious consequence. This opinion views the lack of religious authority of non-Muslim judges as a matter of consensus (ijmāʿ), which, as a primary source of Islamic law, cannot be disputed or overridden by principles of public interest or necessity. The majority prioritizes the theological safeguarding of family law matters from secular authority over adapting ʿurf. Alternatively, this opinion proposes that mosques and Islamic centres, represented by their imams, should be religiously authorized to legitimize civil divorces and certain legal settlements among community members in novel settings.

While all fatāwā, those which ascribe religious legitimacy to civil divorce and those which do not, advocate for communal adjudication, no fatwā precisely demarcates the scope of religious legal authority they would be granted, nor does any establish procedural rules to secure sound religious practices and legal compatibility. As illustrated in the next section, although some Canadian imams incline towards the rationale of the minority opinion in their desire for access to justice, all imams ultimately adopt the conclusion of the majority.

II. What the Imam Says: Qualitative Experiences with Family Mediation

Since, in the absence of Islamic judicial authority in Canada, imams are often called upon to resolve marital conflicts, the present study narrates the experiences of Canadian imams conducting informal ADR services, which, unlike court decisions, are not documented or published. Literature concerning religious divorce and faith-based arbitration predominantly identifies divergences between Islamic and Canadian marital rights schemes, examines past experiences of ADR projects, and surveys the experiences of Canadian Muslim couples navigating divorce processes between religious norms and legal systems.

From 2006 to 2010, Macfarlane collected over 100 personal accounts of marital conflicts through interviews with about 200 divorcees, imams, and social workers across North America from diverse ethnic backgrounds, with approximately a quarter of the participants being Canadian.Footnote 46 The findings describe the phenomena of private ordering in the Muslim community to informally resolve family conflicts following Islamic values without the force of domestic law.

From 2009 to 2013, Fournier interviewed Muslim women residing in Toronto, Montréal, and OttawaFootnote 47 who described how “Muslim marriages and divorces are translated into the Canadian legal order, without direct application of foreign legal systems through conflict of laws.”Footnote 48 Fournier concludes that Canadian conflicts-of-law jurisprudence, which applies the law of the domicile to matters of marriage and divorce, may not, contrary to assumptions, better integrate immigrants nor grant women more rights than foreign Islamic jurisdictions.Footnote 49

In a 2012–2013 qualitative study interviewing ninety MuslimsFootnote 50 from two Canadian cities, Jennifer Selby, Amélie Barras, and Lori G. Beaman offer a different perspective on how Muslim Canadians navigate and negotiate their religiosity. The study presents the participants’ numerous experiences of encountering the secular, reflects on contemporary social scientific scholarship on Muslims, and chronicles the historical settlement trends of Canadian Muslims. The authors critique the reasonable accommodation model “increasingly embraced by scholars and policy-makers,”Footnote 51 arguing that it burdens religious minorities with the onus of requesting formal accommodation, which few Canadians pursue.Footnote 52 The study prefers the navigation/negotiation model, which acknowledges, though does not eliminate, the power dynamics inherent in the reasonable accommodation model.Footnote 53

The present study complements existing qualitative data and socio-legal literature by focusing on the jurisprudential and ministerial perspectives of service providers rather than disputants. While the experiences of the most affected parties, Muslim women, are documented, this research investigates how imams, a position held by men pursuant to Islamic law, conceptualize gendered access to justice issues. Finally, the study frames the issue in a nationwide Canadian context and captures diverse ethnoreligious practices to overcome discrepancies in applying Islamic legal principles.

In 2020 and through 2021, I conducted semi-structured interviews to explore imams’ personal and organizational interactions with the legal system and their views on how Islamic law principles can facilitate religiously acceptable and legally enforceable resolutions. The twenty participating imams are members of different mosques, Islamic organizations, sharīʿah panels, imams’ councils, and fatwā-issuing committees across seven provinces (Ontario, Québec, Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia) constituting the vast majority of the Canadian Muslim population.Footnote 54

Participants were asked five categories of questions: background, jurisprudential, procedural, evaluative, and future recommendations. First, background questions explored the length of their experience with family disputes as religious leaders and whether they obtained any Canadian legal training prior to or during their involvement with such matters. Second, jurisprudential questions discussed their characterization of the conflict between Islamic law and Canadian law as it relates to wife-initiated divorce proceedings and whether Islamic law can accommodate secular procedures, especially in the case of a minority community. Third, procedural questions inquired about ADR methods they employ in providing marital resolution services to their communities. Fourth, evaluative questions assessed the impact of their services by surveying their observations on the “binding effect” of any agreements produced as a result of ADR services, including whether they are filed with courts for enforcement. Fifth, future recommendation questions surveyed participants’ proposals of how the Muslim community can improve its ADR services and institutionally contribute to resolving the gap between religious and secular divorce law.

Background Questions: Demographics of Sample

The interviewees represent diverse communities, ethnicities, institutions, and Sunni Islamic law doctrines.Footnote 55 While three participants were born in Canada, most were immigrants of unique nationalities (Egypt, Lebanon, India, Pakistan, Eritrea, Guyana, Jordan, Sudan, Tunisia, and Algeria), which enriched their appreciation for legal pluralism and diversified their views on access to justice. All twenty participants were imams, some of whom are also religious educators and counselors. Although no uniform credentials are required for an individual to hold the position of an imam in North America, most employers require imams to have general knowledge of Islamic theology and law and to have memorized all or some of the Quran. If these qualifications cannot be met, a community may resort to appointing whomever they deem the most qualified available individual.

At the time this research was conducted, some provinces with small Muslim populations, such as Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan, had very few imams, while other provinces, such as Newfoundland, had none. Some localities, instead, relied on volunteers to conduct religious services or referred to imams from other provinces for religious advice. As such, the participants proportionately reflected the distribution of religious leaders across the country and the population of Muslims in each province (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of imams interviewed, number with legal or ADR training and number born in Canada, by province.

All imams confirmed that family disputes occupy a significant portion of their employment and communal duties. Their experiences in resolving family disputes range from four to fifty years in Canada (four interviewees previously worked as imams in the United States). Imams described that disputes are frequently initiated by women seeking to persuade their husbands to agree to ṭalāq or khulʿ, which, according to a Manitoba imam, is “the biggest challenge we have.” An Ontario imam shared that Muslim women with marriages registered abroad may opt to “go back home to get divorced” by a Muslim judge. Those without marriages registered in Islamic jurisdictions are especially vulnerable to religious abuse by men who can take advantage of their unilateral right to marriage dissolution: “we have seen so many situations where women are abused … which is contrary to the objectives of Islamic jurisprudence.” To proactively combat such abuse, a Manitoba imam explained that he is considering advising Muslim women to ask for the transfer of the right to divorce (tafwīḍ) upon entering the Islamic marriage contract “because there is no other way for them—if something goes wrong.”

Participants asserted that it is uncommon for imams to be trained in Canadian family law or conflict resolution, nor is it a qualification required by their employers. Only three participants obtained Canadian legal training: one completed a mediation and conflict resolution program in Ontario and served as a human rights commissioner in the province for six years, a second holds a family mediation certificate from British Columbia, and a third attended intensive courses offered to his organization by governmental bodies on family dispute resolutions in British Columbia. However, all imams attested that such training is much needed to improve and legitimize their services. An Ontario imam shared that his institution intends to provide legal and social work training for all imams in the locality involved in family disputes.

Jurisprudential Questions: Court-Ordered Divorces Issued by Non-Muslim Judges

While adopting Sunni theology, not all imams formally identify with a particular Sunni school of law (Ḥanafī, Mālikī, Shāfiʿī, Ḥanbalī) in issuing their legal opinions. This reflects the increasingly used legal tool of selectively amalgamating opinions or doctrines from different schools (talfīq). Similarly, the lived experiences of Canadian Muslims, despite general cultural affiliation to particular schools of law, do not reflect doctrinal affiliation or strict adoption of a set of practices prescribed by a singular school of law. This reality decenters the “notion that there is one Islamic orthodoxy or truth, a common misunderstanding about Islam and Muslims.”Footnote 56 Although studying a madhhab is required to attain Islamic legal qualification, there is no recognized hierarchy of scholarship. A few educational programs culturally associated with South-Asian Muslims produce graduates with the distinct titles of muftī and qāḍī. Nonetheless, imams or scholars holding these titles are accorded moral or social authority only over the community members associated with their ethnicity or culture.

All participants reported that the inaccessibility of religious divorce is one of the most contentious issues faced by the community, with Muslim women being vulnerable to a tremendous amount of abuse. As described by a Manitoba imam, “Muslim women are quietly suffering from this and we, as imams and mosques, are sitting there, feeling sorry, and doing nothing… sisters are paying a heavy price on this.” Despite all imams’ admission of the gravity of the situation, most do not automatically grant a religious dissolution of the marriage. According to an Alberta imam, “I do not think an[y] imam with enough Islamic knowledge would rush to issue an Islamic divorce just based on the civil one. In some cases, she [the wife] does not have the right, and I don’t think the imam will jeopardize his knowledge and status just to give a divorce and then put himself in a sharʿī embarrassing and wrong situation.”

All imams, except for one, believe that civil divorce does not confer automatic religious authority. In their view, local Islamic authority is needed to religiously legitimize civil divorces contested by the husband. These nineteen participants disagree with the contemporary Islamic law minority opinion that a secular court-ordered divorce contested by the husband suffices as a form of Islamic marriage dissolution. Only one imam, a member of a North American fatwā-issuing institution, publicly advocates for the minority view, arguing for its practical suitability given the realities of current ADR procedures.

Imams oppose the minority view for various reasons. Some consider it as violating traditional ijmāʿ, which contingent principles of necessity cannot justify. Some perceive lenience in these matters as a threat against the community’s faith identity and erosion of religious and cultural autonomy. Others find no utility in adopting the minority view. As explained by an imam from Manitoba, “I don’t know if people will feel comfortable with that fatwā… theoretically, even if it [is] sound given the circumstances we have… a better alternative which would hopefully satisfy both [legal systems] is maybe a legal divorce enforced or approved by an Islamic institution.” Thus, the Islamic defensibility of the minority view is not the only factor influencing the practices of the community; the parties may not find it legitimate as it does not accord with their sense of what Islamic law demands.

Imams from Québec and Manitoba explained that the community has “a widespread understanding that legal separation through the court is not Islamically binding.” For example, based on this premise, some Muslim couples may apply for legal divorce but remain living together to obtain certain welfare benefits. According to one imam, the common “understanding that legal divorce does not mean anything” is the root cause of recurrent financial and physical abuse. Such abuse is heightened by the fact that some Muslim women are reluctant to seek a civil divorce, even upon the advice of the imams, because of associated stigma: “when [people] hear that she went to the court, that would not look positive on her.” Abusive husbands may also blackmail wives who try to seek civil divorce by accusing them of not being devoted Muslims and of falling into sin.

One imam cautioned against the overuse of the minority argument, critiquing some of fiqh al-ʾaqalliyāt’s jurisprudence: “we need to be careful with the word ‘minority.’ The minority situation will end if I do what? In Islam, we have opinions that can accommodate different situations. I do not feel we are a minority in Montréal… many scholars of sharīʿah are available.” Three imams highlighted the improbability of Canada’s accommodation of Islamic principles because “all secular countries say we have nothing to do with religion.” A Québec imam also explained: “the reality is secular law will never accept religious law. It is impossible for three reasons:” 1) legal practitioners’ illiteracy in sharīʿah, 2) underqualified imams, and 3) communities’ theological and legal diversity, which makes a unified set of rules near impossible.

Procedural Questions: Community-Led ADR Efforts

At least eight participants said they employ collective decision-making in granting faskh, following the classical Islamic law doctrine of communally appointed judges. In deciding whether to grant faskh, they consider factors including the husband’s financial commitments, his absence from the matrimonial home or the country itself, and the wife’s grounds for repudiation. Nonetheless, faskh decisions are rarely made for two reasons. First, imams are wary of assuming the critical role of a qāḍī, even if it is a collective decision. Second, imams exert considerable effort to contact and convince husbands to settle for ṭalāq or khulʿ.

Two imams attempted to standardize the number of times a husband should be contacted and define a timed grace period for his cooperation. However, one imam warned that wives might misinform the imam and intentionally provide wrong contact information for their allegedly unwilling husbands. Admitting the scarcity of community legal resources and their unfamiliarity with legal processes, all imams refrain from facilitating religious divorce or annulment in contested divorce cases before a court order is granted. Hence, some imams attach copies of court-ordered divorces to their issued religious divorces or annulments.

Despite dealing with everyday scenarios sharing cultural norms and religious rules, the procedures adopted by imams providing mediation services highlight differences in their legal characterization of marriage dissolution in the absence or the contest of the husband. For example, an Ontario imam presented a copy of his institution’s standardized forms regarding cases of unwilling or absent husbands. The form confirms that the wife has been separated from her husband, has obtained a civil divorce, and states, “due to the absence of an Islamic court in Canada and our inability to reach the husband to consent to her khulʿ or divorce… according to the Fiqh Council of North America, this is considered an Islamic khulʿ.” The imam said the form is to be attached to the civil divorce order and commented: “I keep a copy in case the husband shows up at any time, so I have something to lean on.” While the referenced fatwā is not found in FCNA’s public archives, the imam asserted that multiple imams, including imams in his institution, apply the characterization of khulʿ to this scenario, a view that contradicts a fundamental element of the khulʿ contract: the husband’s consent. These imams resort to this inaccurate application of khulʿ presumably to avoid the contentious granting of faskh.

Eight imams contributed to establishing local family dispute resolution committees designed to grant faskh or persuade the husband to settle for ṭalāq or khulʿ agreements (Figure 3). Further, these committees provide Islamic-compliant corollary relief to be incorporated in domestic contracts and, in a few provinces, examine the potential for Islamic arbitration.

Figure 3 Reported family ADR committees of which some participants are members: three committees in Alberta and one each in Nova Scotia, British Columbia, and Québec.

Nova Scotia

A family support committee (FSC) was established in Nova Scotia to unify religious opinions and promote consistent practices across recurring scenarios. The FSC’s mandate is to resolve family issues by drafting prenuptial and separation agreements to be filed in court. As a communal project, the FSC consists of three imams, two social workers, a family counsellor, and two administrative representatives of local Islamic organizations who work alongside an advisory group that includes a family lawyer and psychologists. Since it launched in April 2020, the FSC has dealt with ten to fifteen cases. No accounts of judicial enforceability of such domestic agreements have yet been reported. To raise awareness of religious laws and legal rights, the FSC advises community members to include a clause in their prenuptial agreements dictating that disputes are to be brought before the FSC. The FSC plans to expand its services to include granting Islamic arbitral awards and seeks to register one of its members as a licensed arbitrator.

Alberta

Alberta has the second-largest and one of the oldest Canadian Muslim populations. Three of the four Alberta imams described their roles in unique committees and councils that provide religious remedies for “complicated cases.” While imams may deal with cases independently, they refer specific scenarios to monthly council or committee meetings for collective decision-making. Two committees established in one city were tasked with a faskh mandate; each consists of at least three imams. Although they follow consensus-based decision-making, a member of one of these committees said that some cases could be dealt with by a single committee member. At the time this research was conducted, all of these committees were operating pursuant to unwritten rules of procedure and frequently consult legal professionals. One of the committees seeks to develop an umbrella council approved by most of the province’s imams to offer Islamic arbitral awards in accordance with provincial arbitration laws.

To overcome discrepancies in religious opinions and guarantee cultural inclusivity, one of these committees ensures representation of the four Sunni maḏhāhib and employs talfīq to identify the law applicable to the given circumstances. No particular school of thought is consistently adopted. Instead, a practical opinion is reasonably selected based on relevant customary standards. One of the primary considerations in selecting an opinion is the competition with the civil scheme of spousal rights; the opinion that entitles the wife to the relief most comparable with Canadian law is likely to be applied. For example, the committee assigns the husband a responsibility to pay spousal support continuously for two years following an Islamic law opinion also adopted by Egyptian family law.

British Columbia and Quebec

In British Columbia, a Sharīʿah Advisory Panel functions under the board of one of the oldest Islamic organizations in the province. The panel consists of a minimum of three members and only deals with faskh cases. No mediation resulting in domestic contracts or arbitration is provided. In Québec, a provincial imams’ council established a “Fatwā, Ṣulḥ, and Dispute Resolution” committee, in part to deal with cases of faskh, khulʿ and contested divorce. Currently, the committee is seeking to institutionally define the roles of its members and document some of its adopted procedures. As a member of this committee described, “it takes tremendous effort and months to find the man… The woman might have to wait for up to eight years to solve her issue. An institutional solution will make these things a lot easier and will be more protective of those providing the service.”

Evaluative Questions: Inadequacies and Suggestions

In assessing the impact of their ADR services, imams highlighted several concerns about how they operate, primarily the absence of uniformity, the lack of legal or religious enforcement authority, and the fear of personal liability upon intervening in private matters.

Non-uniformity

Imams unanimously expressed dissatisfaction with the current ad-hoc dispute resolution structures because they rely on ambiguous religious or legal authority: “because there is no clear authority, every Islamic centre does whatever it wants to do.” They believe such undocumented services lead to inaccurate decisions, explaining that the lack of administrative oversight allows under-qualified or self-appointed imams to rule on life-changing decisions: “Some imams are default imams. Somebody’s father owned a centre, then he becomes the imam after him. He has absolutely no background or knowledge… or certification in sharīʿah studies… Anybody can be an imam.”

This statement was confirmed by a Manitoba imam, stating that “there is no clear criteria [for] who becomes the imam.” Many imams offer these services free of charge and outside of their formal job duties, which further reduces oversight of their actions.

Three imams shared accounts of individuals taking advantage of the unregulated profession by offering covert paid services of granting religious relief to community members without proper qualifications or oversight. Those individuals are accused of abusing their informal or formal religious positions and assuming the role of a Muslim judge to grant verdicts. All participants affirmed such unchecked authority is fertile ground for potential religious, social, or emotional abuse. It also runs the risk of making decisions based on cultural traditions rather than Islamic law or in contravention of Canadian law (e.g., cases involving minors, polygamy).

Another factor contributing to the non-uniform outcome of ADR services stems from the ethnic and religious diversity within the Canadian Muslim community. A dominant characteristic of modern Muslim societies is the irregularity of following a particular school of law or modern religious authority. Given the abundance of procedural differences across the maḏhāhib and the various legal methodologies individual imams adopt, imams mentioned that disputants frequently seek the simultaneous involvement of multiple imams belonging to different legal schools to obtain particular religious opinions they find favourable to their interests. Disputants, unsatisfied with one imam’s suggested resolution, may thus fall into “fatwā shopping” for their desired resolution. To avoid this, a Québec imam offered that “the community needs to agree on certain rules and codify some of the Islamic laws on how to deal with different cases.”

Lacking Enforcement Power

All imams expressed frustration with the lack of enforceability of their suggested or mediated resolutions, which take significant time and effort to reach. An Alberta imam said, “we do not have any binding authority in this area [of law], and we have to admit that.” A Manitoba imam added, “we do not have any legal authority … just moral authority.” As such, the religiosity of the parties was identified as a strong indicator of parties’ obedience to resolutions reached through faith-based mediations. An Alberta imam estimated that in 80 percent of the cases he dealt with, parties ended up abiding by the agreement after receiving independent legal advice. The reason, according to him, is that he would always remind parties of the Islamic principles of keeping promises and honouring one’s agreements. An Ontario imam confirmed that “people who are religiously oriented are the ones who usually abide by it. Otherwise, they do not. They end up seeking a lawyer… or go straight to the court.”

However, relying on the religiosity of parties, such moral authority does not make up for the lack of legal and religious power to bind disputants to their negotiated resolutions: “we do not have any enforcing power. All we can do is try to reconcile between people… I do not think any imam has the [religious] authority of the [Islamic] judge.” A Québec imam also confirmed that “most couples do not abide, and they go to court.” A British Columbia imam explained that the voluntary nature of the mediation processes might be the reason why disputants do not abide by their resolutions, adding that imams are not typically involved to conduct court-required mediation, which may be taken more seriously.

Other imams encourage couples to add their resolutions to legally binding and enforceable separation agreements. An Alberta imam explained the merit of being involved in drafting domestic contracts: “I have done this many times… The only way I push it to be binding is to have it notarized and certified by the legal representatives of both parties. Other[wise], I don’t think people will take it seriously.” A British Columbia imam described his more limited means of participating in domestic contracts, which is to only draft a memorandum of understanding between the parties so that they can submit it to their lawyers upon drafting the agreements.

Although imams often encourage couples to enter into prenuptial agreements to guarantee the enforcement of religious rulings, none of the participants encountered parties with such domestic contracts. Some participants try to provide provisions for separation agreements to ensure compliance with Islamic law and achieve effective results from their mediation services. An Alberta imam described that he and the couple collectively draft the agreement according to Islamic law and the couple’s situation, and the parties are then instructed to sign it, witnessed by their lawyers, prior to the imam signing it himself. Some committees even facilitate access to lawyers to provide required legal services. Due to the unenforceability of religious arbitration in Ontario and Québec, imams in these provinces are uncertain as to whether their negotiated agreements are ultimately filed in court and doubt their enforcement as domestic contracts even if they are filed.

Fear of Liability and Social Repercussions

Participants consistently stressed concerns about the risks of professionally engaging in legal disputes. Notwithstanding the desire of an Alberta imam to provide arbitration, presumably enforceable in the province, the institution managing the mosque refrained from doing so because of liability concerns. Such fear is not merely hypothetical. One imam reported that he was directly threatened with being personally sued for “spiritual neglect.” A second imam was accused of harassing an ex-wife after attempting to convince her to not change her child’s name following divorce. To avoid such issues, an Ontario imam mentioned that he sometimes puts disputants under an Islamic oath protecting the confidentiality of the settlement procedures.

Concerns for conflicts of interest or perceived biases, such as favouring large donors to affiliated mosques, are rampant. At least four imams expressed ongoing concerns about having their reputation harmed throughout the community for not reaching a particular outcome. Another Ontario participant shared that some members of a panel formed to grant faskh “were threatened by the husband [and] assaulted. One imam was assaulted twice, so we stopped doing faskh.” Most participants believed these concerns could be alleviated by structural support for dispute resolution services and formally documented procedures and policies.

Suggested Proposals

In an absolute affirmation of the need for a resolution from within Islamic law, all imams emphasized the importance of institutionalizing Islamic ADR, educating religious leaders and the community on legal rights and obligations, and advocating for faith-based arbitration: “I think it is easy and doable, but it needs some work from the Muslim community,” an Alberta imam said. All participants also agreed that providing Islamic ADR would increase access to justice. According to a British Columbia imam, “Just as there are ADR mechanisms that work within the current system… if Muslims could also work within the legal system, that would actually be of benefit to the huge backlog we see in the courts nationwide. It [would] be a voluntary system, so we are not imposing judgments on anybody that does not want to be there.”

Participants consistently highlighted committing to Canadian law while not compromising Islamic values: “we have a commitment towards our religion, and we have a commitment towards the law of our land,” an Alberta imam said. A Québec imam added: “I do not believe Muslims will drop this [Islamic laws] and say we will take the rules of the civil law.” The need for Islamic ADR was consistently framed as a solution to relieve the secular legal system of resolving issues outside of its capacity. As elaborated by a British Columbia imam, “We cannot expect that a non-Muslim judge will be entirely aware of the intricacies of this process or would value it as Muslims do … It is not that Muslims want a parallel legal system here. It is, rather, what I believe most Muslims want, is some way to incorporate these few additional things into the current legal system.”

However, whether the community or religious leadership has the institutional capacity to create a compliant system is uncertain. One of the imams suggested that Islamic institutions need to formalize “procedures rather than leaving it up to each imam to make their own judgment… but… which Islamic institution? Are the imams qualified to exercise this? Do they have the necessary legal and fiqh understanding?” The expertise and resources needed to establish such a system are also dependent on the size of the community. Thus, some imams from different provinces incline towards “a national project, not just a provincial project” since “it will be too much for communities like us to take the lead on this because you need experts and scholars— this is where we look to leadership from larger national organizations.”

The promising experiences of Islamic ADR procedures in Alberta and Nova Scotia stand in stark contrast to the paralyzed state of affairs in Ontario and Québec. However, imams from Alberta and Nova Scotia involved in developing the arbitral services in those provinces expressed concerns about potential adverse public reactions, given the hostile experience of the 2006 Ontario controversy.Footnote 57 Upon being asked if any imams in Alberta seek to apply religious family arbitration since it is provincially allowed, one Alberta imam said: “after what happened in Ontario, we do not want to repeat the problem again or put effort [in]to build[ing] something [which] then [would] not succeed.” Indeed, a Québec imam noted his negative experience in attempting family ADR: “they came out in the media and said ‘sharīʿah law,’ and it was a big issue.” In this way, initiatives to systemize religious mediation services to assist in creating domestic contracts were halted, perhaps as an unintended consequence of the 2006 Ontario ban on using religious law in arbitration.

Nonetheless, imams remain hopeful regarding the establishment of Islamic ADR institutions. A Québec imam emphasized the importance of community advocacy to reach this goal: “Muslim minorities all over Canada should push for this to happen. We have good examples from the UK and the US. It is also important for us in Canada to have a system like that. I wish we could convince the government to give us a chance to try. I am sure we will see a positive impact.”

Most recently, the Canadian Council of Imams delegated Canadian Muslim scholars with the task of developing Islamic ADR protocols that standardize solutions for recurring scenarios (e.g. unwilling husband, deceased or lost husband, unregistered marriage) and build a flexible panel structure that local communities can adapt to operate in harmony with their respective provincial laws governing mediation and arbitration.Footnote 58 To avoid the reported risks, “stringent measures must be taken to ensure that only qualified individuals are allowed to participate” and “proper procedures are being followed.”Footnote 59

The interviews highlight the inconsistent application of Islamic law as exercised by Canadian religious leaders or adopted by community members. The following concerns inform imams’ recommendations for Islamic ADR: liability for assuming unauthorized roles, lack of religious and civil enforceability for their resolutions, individualistic practices prone to irregularity, and fear-mongering publicity driven by Islamophobia. Imams are nonetheless eager to contribute to developing holistic solutions to these concerns driven by values of freedom of religion, self-regulation, communal oversight, and gendered access to justice.

III. Conclusion

Despite upholding individual liberties, liberal regimes may pressure Muslims to adapt to practices unrecognized by their faith. The failure of many informal dispute resolution practices drives Muslims to bargain their religious rights by resorting to state-administered judicial forums, which grant secular relief inconsistent with the Islamic faith. In exploring how Islamic law principles are interpreted by fatāwā and exercised by Canadian religious leaders in resolving marital conflicts, this article provides an account of the intersection of religious values and practices and secular legal systems. Islamic family law represents “most of what remains of the pre-colonial Islamic legal system,”Footnote 60 a fact that shapes imams’ advocacy for self-regulated ADR forums and informs the socio-political identity of Muslims in modern nation-states.

Although a few dissenting opinions attempt to grant religious legitimacy to contested secular court-ordered divorces, most Muslim scholars and Canadian imams, reflecting the practice of a large segment of the Muslim community, do not automatically uphold civil divorces as Islamic divorces. While the doctrine of necessity can accommodate relaxed qualifications for qāḍīs, it cannot religiously validate secular court orders issued by non-Muslim judges. Muslim jurists across history facilitated access to justice by supporting communally appointed qāḍīs. These two adaptive Islamic law frameworks—the doctrine of necessity and communally-appointed judges–inform the work of the Canadian Muslim community to establish representative entities that facilitate ṭalāq or khulʿ and grant faskh. The data presented confirms the need to strengthen community-initiated ADR mechanisms and may serve as a springboard for future research and law reform projects.

Further research may aim to conceptualize the moral responsibilities and legal identities of Muslim minorities. Premodern Islamic jurisprudence affirms certain ethical standards for living under non-Muslim polities, chiefly the insistence on the inviolability of contracts.Footnote 61 As such, does Islamic law, by virtue of social contract obligations, morally oblige Muslims to abide by non-Islamic family laws and court orders decided by non-Muslim judges? Construing such ethics and jurisprudence as an abstract social contract, what are the boundaries of accommodating secular adjudicative norms? How does Islamic law characterize Muslim existence under non-Muslim authority and what is the demarcation of a “Muslim minority”?

On the other hand, to what extent can the secular conception of legal pluralism accommodate Muslim community-led adjudication of family matters? Arguments supporting and opposing community-led adjudication draw on conceptions of legal pluralism, equality, freedom of religion, and social contract theory. Proponents argue for accommodating religious minorities by expanding their “jurisdictional autonomy”Footnote 62 although not in a way that amounts “to a kind of delegation of state power to an imagined Muslim collectivity.”Footnote 63 Opponents, meanwhile, advocate for one law for all to establish equality and protect the rights of vulnerable individuals. Legislation should permit faith-based resolutions to be enforced akin to other contracts or arbitral awards; the existence of procedural unfairness voids either instrument under existing common law. Specifically excluding faith-based instruments from enforcement does not afford vulnerable parties any added protection but merely adds barriers for minorities attempting to resolve their disputes outside of court.