Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) is an opportunistic interstitial fungal pneumonia. Reference Kelly and Cronin1 Colonization with P. jirovecii occurs in more than 50% of the general population; however, symptomatic infection is rare. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients and other immunosuppressed patients can develop PJP. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2

The clinical presentation of PJP includes a low-grade fever, shortness of breath, and a dry cough. Reference Kelly and Cronin1,Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 On physical examination, patients experience tachycardia and tachypnea with minimal findings on chest auscultation. Reference Kelly and Cronin1,Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 In HIV patients, the presentation is more subtle, while non-HIV patients will present with rapid onset respiratory failure. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 Accordingly, mortality rates in HIV patients are 10%–20%, while in non-HIV patients this rate is 30%–60%. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2

The incidence among non-HIV immunocompromised patients is rising (6.2%), likely as a result of the increasing use of immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of malignancies, autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and bone marrow or solid organ transplants. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 Neurosurgical patients are frequently managed with high-dose steroids, particularly in the perioperative period. Reference Merkler, Saini, Kamel and Stieg3 In some cases, steroids are continued long term, particularly in the context of adjunctive radiation treatment. Reference Hughes, Parisi, Grossman and Kleinberg4 Guidelines for PJP prophylaxis among HIV patients are well established, while prophylaxis in neurosurgical patients is variable. Reference Kelly and Cronin1 Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (TMP/SMX) is effective to reduce the incidence of PJP infections in non-HIV patients (6.2% vs 0.9%). Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 In this article, we present two neurosurgical patients presenting with PJP following steroid exposure. A review of the literature is presented with the objective of providing an update to recommendations useful to teams caring for neurosurgical patients.

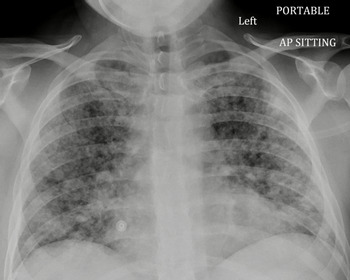

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 6-month history of left eye progressive central visual blurring that improved with lateral gaze. Her past medical history was significant for poorly controlled essential hypertension. Computer tomography angiogram of the head revealed a 5.2 × 5.2 cm supraclinoid internal carotid artery aneurysm. She underwent successful urgent endovascular occlusion of the left internal carotid artery proximal to the aneurysm. She was discharged home 5 days postoperatively on a dexamethasone taper and aspirin. Two months after discharge, she presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-week history of confusion and malaise 3 days after stopping dexamethasone. In the ED, she developed rapidly progressive hypoxemia and required endotracheal intubation and ventilation in the intensive care unit (ICU). Chest X-ray (CXR) demonstrated diffuse bilateral patchy infiltrates (Figure 1). In the ICU, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was positive for PJP. Fortunately, she improved quickly on ventilatory support, TMP/SMX, and prednisone. She was extubated and discharged home.

Figure 1: AP chest radiograph demonstrating diffuse, bilateral, patchy, and confluent infiltrates with a predominant perihilar distribution.

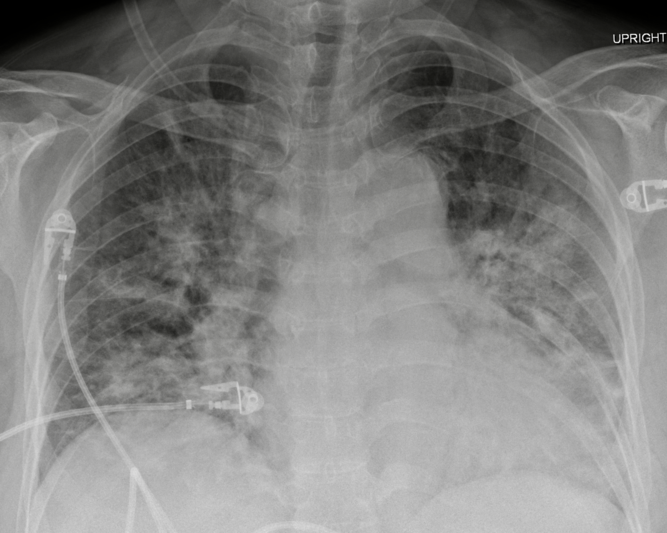

A 31-year-old male presented with a 2-year history of progressive headaches, nausea, vertigo, bilateral arm paresthesias, and blurry vision. His past medical history was unremarkable. A magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an enhancing lesion of the posterior fossa and obstructive hydrocephalus. He underwent urgent suboccipital craniectomy and the surgical pathology was consistent with a WHO grade 4 medulloblastoma. After in-patient rehabilitation, the patient was discharged home on dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily (BID) with a plan for radiation followed by chemotherapy. Three weeks later, the dexamethasone dose was increased by the patient’s family physician to 8 mg BID. Three months after surgery, he presented acutely to the ED with a history of fever, chills, and dry cough. He had features of sepsis with tachypnea, tachycardia, and relative hypotension. His initial CXR was largely unremarkable and his oxygen saturation was normal on room air. He was started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Two days following his admission to the internal medicine team, he developed acute respiratory failure. Repeat CXR was most consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome ( Figure 2). He was transferred to the ICU for intubation due to profound hypoxemia. BAL was positive for PJP. He was started on high-dose TMP/SMX and steroids. He deteriorated despite lung protective ventilation, neuromuscular blockade, lung recruitment maneuvers, prolonged prone positioning, and inhaled epoprostenol. Comfort measures were instituted and he passed away peacefully in accordance with his previous wishes.

Figure 2: AP chest radiograph demonstrating diffuse, bilateral, and nodular parenchymal opacities.

Increased lung inflammation in HIV-negative patients likely contributes to faster disease progression, with more severe hypoxemia, greater need for intensive care, and higher prevalence of shock. Reference Limper, Offord, Smith and Martin5,Reference Roux, Canet and Valade6 Limper et al Reference Limper, Offord, Smith and Martin5 used BAL to quantify pneumocystis and inflammatory cell numbers; HIV-negative patients had greater neutrophil counts, correlating with worse oxygenation and decreased survival. Latency to diagnosis also likely contributes to increased mortality in this population. Reference Roux, Canet and Valade6 High-dose steroids increase the risk developing PJP due to immune system impairment. Reference Yale and Limper7 A case series from Mayo found that in 91% of HIV-negative patients with the first episode of PJP, glucocorticoids had been administered within 1 month of diagnosis. Reference Yale and Limper7 Yale et al Reference Yale and Limper7 concluded that patients receiving prolonged, high-dose corticosteroid treatment (16–25 mg prednisolone or >4 mg dexamethasone daily for >4 weeks) are at high risk of PJP infection, regardless of underlying type or stage of malignancy, or use of other chemotherapeutic agents.

Glucocorticoids in neurosurgery are used to reduce inflammation and vasogenic edema. Reference Merkler, Saini, Kamel and Stieg3 PJP infections occur primarily during steroid taper in patients with primary brain tumors. Reference Hughes, Parisi, Grossman and Kleinberg4 The dose reduction during a taper may allow for an increased inflammatory response that unmasks a latent infection. Reference Hughes, Parisi, Grossman and Kleinberg4 Radiation therapy has also been shown to cause increased myelosuppression, further increasing the risk for PJP infection. Reference Hughes, Parisi, Grossman and Kleinberg4

PJP prophylaxis is recommended when the risk of PJP is greater than 3.5%. Reference Cooley, Dendle and Wolf8 The overall incidence of PJP infection among patients with primary or metastatic CNS tumor is low (1.7%), but with concurrent radiation this risk increases to 6.2%. Reference Cooley, Dendle and Wolf8 First-line PJP prophylaxis is TMP/SMX. Other effective antimicrobial agents include clindamycin, atovaquone, pyrimethamine, sulfadoxine, dapsone, and pentamidine. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 The 2014 Cochrane review concluded that TMP/SMX administered three times per week was as effective as once daily. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2,Reference Cooley, Dendle and Wolf8 Potential side effects of TMP/SMX include skin rash, leukopenia, liver, and renal dysfunction. Reference Stern, Green, Paul, Vidal and Leibovici2 PJP prophylaxis should be instituted immediately and continue for 6 weeks following the steroid taper period. Reference Cooley, Dendle and Wolf8

There are currently no standardized guidelines for PJP prophylaxis in neurosurgical patients. Collecting before and after data and performing an economic analysis are warranted. We recommend protocolized care with systematic prescription of TMP/SMX three times a week in neurosurgical patients undergoing treatment with prednisone equivalents of 20 mg daily for 4 weeks or longer in duration.

Conflicts of Interests

None.

Statement of Authorship

MdeLB, MD, and PC were all involved in the project conception, authorship, and editing of the manuscript.